1. Introduction

Organizational sustainability has been a core issue in tourism and hotel corporations that thrive in an unstable yet aware world. That is why these organizations are at the interface of environmental responsibility, social impact, and economic sustainability (

Khatter, 2023). Therefore, there is nothing wrong with the notion that sustainability cannot be achieved on an operational or compliance basis but must be a strategic requirement (

Ali et al., 2025). It involves the power of an organization to thrive, adapt and innovate to survive as it keeps in tandem with general environmental and societal objectives (

Saemaldaher & Emeagwali, 2025). In this context of dynamics, internal organizational factors are turning out to be just as significant (or even more) as external pressure in the determination of sustainable results (

F. Khan & Badulescu, 2025). The highlighted internal factors are internal influences including talent management, green knowledge sharing, and green employee voice, which are ranked as the most influential. These are the humanistic dimensions of internally attaining a culture of sustainability (

Al-Romeedy & Alharethi, 2025). More specifically, talent management is an essential practice as it aligns company hiring, training, and retention in a manner that confirms not only the ability but also the values of the persons that positively relate to environmental and social responsibility (

Mujtaba & Mubarik, 2022). The strategically managed talent pool is transformed into a driver of innovation, agility, and long-term value creation, so that the organization could goal-seek towards sustainability purposes with consistency and coherence (

Yomralıoğlu, 2025).

This significance of talent management in the tourist and hospitality industry is rather high because of the labor-intensive and service-based character of the business (

Abid et al., 2025). The entities in this industry depend on the quality of people, innovativeness, and dedication of their employees to offer quality experiences to their customers as they handle the environmental imposition of their activities (

Al-Romeedy & Singh, 2026). By prioritizing environmental awareness, ethical conduct, and the engagement of employees over the long term in the creation of talent management systems, one can precondition the overall life-altering change in the organization (

Umair et al., 2024). In addition, the degree to which employees would volunteer and gain skills to share green knowledge and voice their concerns and innovations related to sustainability are based on their talent management practices (

Nazir et al., 2025). Through its inclination to build a climate of trust, support, and inclusion, talent management has the power to enable the organization to unlock the potential of its employees in the context of change agents of its own sustainability process (

Cascio & Aguinis, 2024).

Tightly interlined with the notion of talent management are the concepts of green knowledge sharing and green employee voice, which are critical in the process of encouraging individual schooling to mutational group learning and performance. Green knowledge sharing means the exchange of information, practices and insights concerning the environment between the employees, the departments and the leadership. Knowledge sharing leads to greater awareness in organizations and innovation, as well as better environmental performance (

R. Khan et al., 2023;

Abbas & Khan, 2023). Whenever employees feel empowered and supported, they are bound to share such knowledge enthusiastically, leading to a learning-based and adaptive culture which is a consistent feature of sustainability (

Mahmoud et al., 2022).

At the same time, green employee voice is the active initiative on the part of individual employees to express ideas, suggestions and concerns concerning environmental enhancement in the work environment. It demonstrates how employees are ready to raise their voices in the name of sustainability, challenges malpractices that are not sustainable, and presents ideas that will benefit the green objectives in the organization (

Gaafar et al., 2021). Promoting green voice does not only favor transparency and ethical conduct, but it also results in the more holistic processing of decisions and organizational responsiveness (

Hu et al., 2025).

Although the debate around sustainability in the tourism/hospitality industry continues to grow in the last few years (e.g.,

Khatter, 2023;

Umair et al., 2024;

Mahmoud et al., 2022), most research still focuses on the external or structural factors that serve as determinants of sustainability (e.g., regulatory compliance, environmental certifications, or technological solutions). It has effectively sidelined the contribution of internal and human-centric processes—that are grounded in talent management and the behavior of the employees, especially in long term sustainability. It is seen that the existing literature does not consider and take into account the modest, yet influential, modus operandi by which employees can and do make contributions relating to environmental initiatives, notably with informality of behavior whereby there is the sharing of green knowledge, and environmentally instigated voice. In addition, the studies which consider human resource practices in this context are limited, and those which do are inclined to address sustainability as a by-product of generic employee engagement (e.g.,

Lu et al., 2023;

Diaz-Carrion et al., 2020;

Graham et al., 2023), as opposed to probing the possibilities of how specifically configured talent systems can engage pro-environmental behaviors. This is a major omission in the tourism and hospitality industry where the delivery of service strictly depends on the performance of its employees (

Al-Romeedy & Alharethi, 2025). Evidently, there is gap in knowledge between how talent management could be strategically positioned not merely in upgrading process efficiency, but also in developing a work force that is environmentally conscious and behaviorally invested towards sustainability values.

By addressing these conceptual and empirical breaches, the study at hand ventures to decipher the inner dynamics between talent management and organizational sustainability by giving emphasis to the mediating role of green knowledge sharing and green employee voice. Precisely, the purpose of the proposed study is to (A) evaluate the impact of talent management on the organization sustainability, green knowledge sharing, and employee voice (green); (B) investigate the impact of green knowledge sharing and green employee voice on sustainability within the organization and (C) test the new mediating role of green knowledge sharing and green employee voice in the relationship between management of talent and sustainability within the organization. It is the aim of the research to provide a theoretically saturated and empirically based model through which employees are reframed as key actors during sustainability transitions. It goes beyond traditional paradigms of managing sustainability as a top-down mandate and rather envisions it as an ongoing bottom-up process enabled by an educated staff. By this prism, the study can be seen to contribute to the evolution of the sustainability theory in the context of achieving the integration of behavioral, strategic and environmental thinking in one domain. At a practical level, it empowers tourism and hospitality institutions with a good basis to rely on in terms of establishing the conduct of talent management practices that not only attract and retain quality personnel but also have them turn into custodians of ecological intelligence and cultural change. The results should be able to push the concept of sustainability beyond structural policy and emphasize more on the importance of human capabilities and social exchange and collective voice in creating environmentally resilient organizations.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Talent Management

Talent management represents a strategic approach that focuses on identifying the most critical positions within an organization and working to attract, develop, and retain high-performing individuals to fill these positions to ensure long-term success. This approach adds significant value to the organization by linking human capital to strategic objectives, enhancing innovation capacity, and achieving a sustainable competitive advantage (

Greene, 2020). The importance of talent management lies in its ability to ensure that the most influential individuals within an organization are continuously supported and developed, which impacts the quality of organizational performance and the effectiveness of strategic decisions. In sectors that rely heavily on human resources, such as tourism and hospitality, talent management becomes a critical factor in achieving customer satisfaction and improving business sustainability (

H. Zaki & Al-Romeedy, 2019).

It is important to distinguish between talent management and general human resources practices. While human resources practices aim to manage all employees through activities such as recruitment, training, compensation, and evaluation, talent management focuses specifically on a subset of employees who are perceived as having high strategic value to the organization. Talent management is thus a more specialized extension of human resources, focusing on the roles and individuals that can make a significant difference to the future performance of the organization (

Majumder & Dey, 2023;

Greene, 2020).

2.2. Social Exchange Theory—SET

The Social Exchange Theory (SET) is a strong conceptualization of the interplay of internal forces of how talent management operates to cause sustainability in tourism and hospitality organizations (

K. Zaki & Elnagar, 2025). Underlyingly, the principle of reciprocity is the foundation of SET, which implies that every time organizations engage in practices that are supportive to the employees, like training, knowing how to empower them, treating them fairly and recognizing their effort, employees will feel that they have a pay them back to work with positive behaviors for the organization (

Alkhozaim et al., 2024). The management of talent in this scenario does not solely signify a convenient process of HR work but a mechanism of relationship which indicates trust, significance, and prolonged initiative towards the employees. In cases where employees sense that their organization is highly interested in their personal development and also takes into consideration the well-being of employees, the more they will tend to exhibit discretionary behaviors that are not related to their formal roles. Such actions are performing proactive measures towards the sustainability of the organization, especially through transferring knowledge relevant to the environment and voicing green practices and improvements (

McDonnell & Wiblen, 2020).

In this theory, green knowledge sharing and green employee voice are interpreted as mutual reactions to favorable treatment in the organization (

Rubel et al., 2021). However, favorable treatment alone does not necessarily result in pro-ecological actions, as it could equally coexist with practices that overlook or even exploit the natural environment. For green knowledge sharing and green employee voice to emerge, favorable treatment must be embedded in an organizational climate that explicitly values sustainability, sets clear expectations for pro-environmental behavior, and provides employees with opportunities and support to transfer ecological knowledge. Under such conditions, employees are more likely to interpret favorable treatment as a signal that their organization prioritizes environmental responsibility, which in turn motivates them to share green knowledge and voice their ecological concerns constructively (

Majumder & Dey, 2023;

Yajman, 2025;

Tiwary, 2025). SET describes the development of these mediating variables as voluntaries and thus trust-based actions in terms of which employees demonstrate their devotion to organizational values and that is with respect to environmental stewardship (

Rajâa & Mekkaoui, 2025). Talent management systems enhance the way the employees perceive their treatment as they feel more respected and empowered than before, which results in them being more likely to share their knowledge and share their ideas connected to environmental improvement even without being explicitly asked to. Such types of active involvement are directly connected with organizational sustainability that can be promoted through innovations, collective awareness, and adaptive behaviors (

Al-Romeedy, 2023a). In this way, apart from establishing the relationship between talent management and the outcome of sustainability, SET explicates the psychological and relational attainment, mediated by green acts, where the relationship materializes (

Paillé et al., 2023). This conceptual fit adds vibrancy to the fundamental argument of the study that internal human-based practices form the foundation in promoting sustainable change within (see

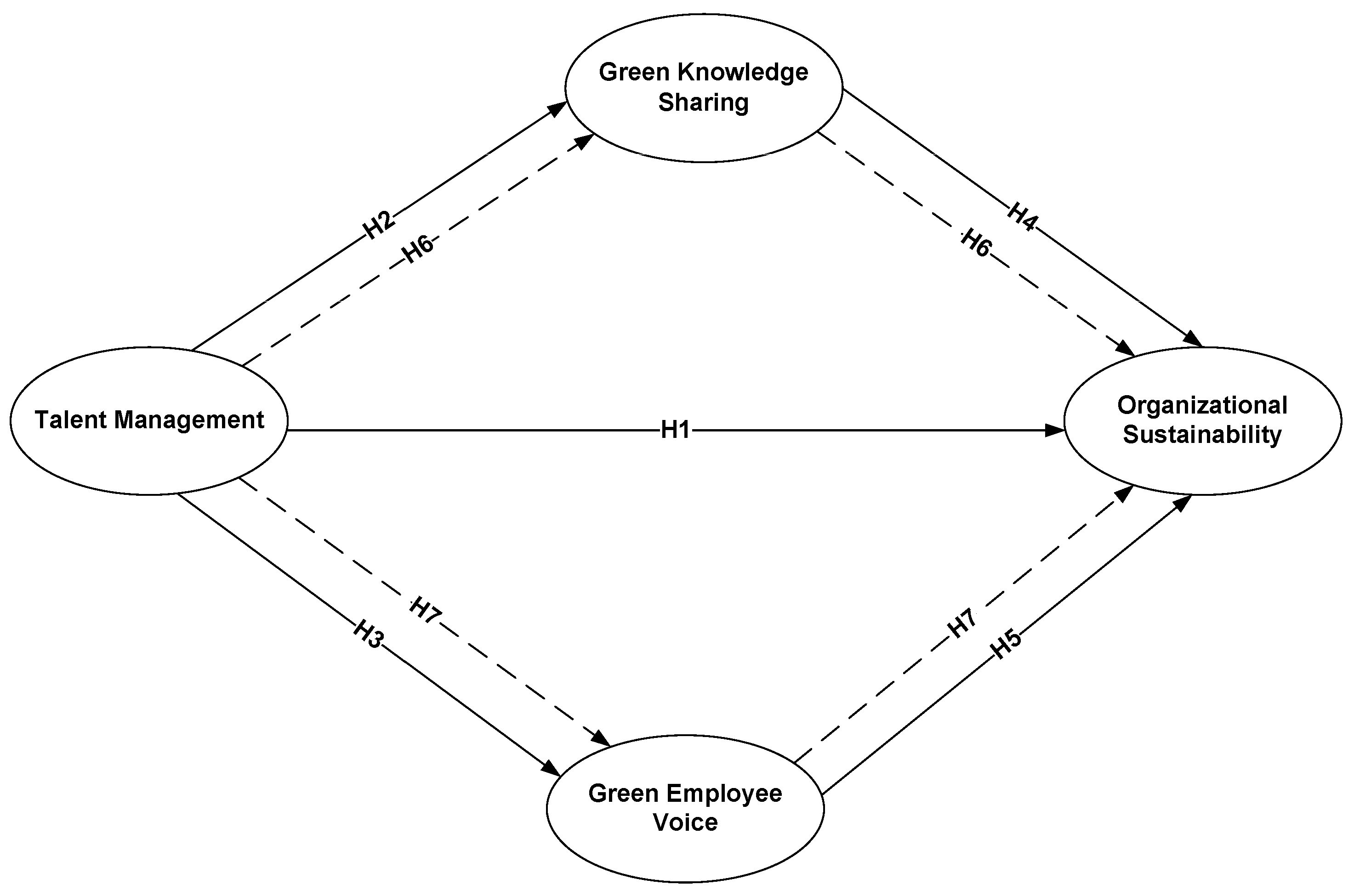

Figure 1).

2.3. Talent Management and Organizational Sustainability

Against the backdrop of the sustainability-focused contemporary business environment, the pressure on tourism and hospitality-related organizations to combine their internal human resource strategies with the rest of the environmental and social goals is steadily rising (

Mahran et al., 2025). When transformed into a strategic process, talent management surpasses its traditional purpose of attracting and retaining employees as the key advocate of the organizational transformation (

Taylor, 2018). Organizations have consciously invested in talent development, skills, leadership nurturing, and ensuring value alignment that facilitate a fertile environment in terms of thinking and behavior in the long run (

Elegbe, 2016;

Cascio & Aguinis, 2024). It is not only operational but also influences the identity of organizations, instills sustainability into practices, and the ability of workers to perform in a manner that suggests long-term ecological and social accountability (

Greene, 2020). Additionally, companies that institutionally embed talent management as a strategic asset have enhanced chances of being able to adjust to sustainability realities, utilize employee competences to green innovation and institutionally embed sustainable practices across functions. Such points of consideration create an underpinning scenario in which talent management serves as a driver of integrating sustainability into the organizational vein (

Yomralıoğlu, 2025;

Adamsen & Swailes, 2019).

Al Aina and Atan (

2020) emphasized that workforce development, employee performance alignment, and other strategic talent practices are critical in the promotion of sustainable results. Likewise,

Mujtaba and Mubarik (

2022) established that an investment in talent will promote long term orientation and environmental awareness to the employees, which reinforces the integration of sustainability. There was also the value that

Tunio et al. (

2023,

2024) placed upon the importance of talent systems leading to sustainability since the system helps to develop adaptive capacities and encourage employees to make environmentally sound decisions.

Almaaitah et al. (

2020) managed to prove that management of talents leads to organizational resilience and ethical commitment, which are both essential elements of sustainable performance. On the same note,

Sumathi and Sumathi (

2022) determined the higher degree of green values and long-term strategic thinking to be institutionalized in talent-aware organizations. Lastly, these findings were reaffirmed by

Al-Romeedy (

2023b,

2024) who used the example of talent management as a driver to internalize sustainability in the culture of tourism and hospitality businesses. Such an explanation gives rise to the following hypothesis:

H1. Talent management has a significant positive effect on organizational sustainability.

2.4. Talent Management and Green Knowledge Sharing

Knowledge is viewed much more as an essential intangible asset of tourism and hospitality organizations aiming to promote sustainable practices, especially environmentally oriented knowledge. The extent to which such knowledge goes around internally does relate to the organizational forms but also to the mental atmosphere created by talent management (

Al-Romeedy & Alharethi, 2024a). By selecting, developing, and supporting employees within learning-valuing, open-valuing, and purpose-valuing systems, the employees become more likely to practice voluntary knowledge sharing, including sharing green ideas, practices, and innovations (

Rubel et al., 2021). The manager of the talent can strengthen the climate on which such an exchange can be met through the development of competency through collaboration and the development of a vision that is common and sustainable (

Chew & Mohamed, 2024). Specifically, mentoring, environmental training, and leadership empowerment are development-centered practices that can have the benefit of informing the employees that their knowledge and skills are valued—in turn, encouraging them to share their knowledge to ride environmental objectives (

Yan et al., 2024). Instead of the traditional approach of being passive and receiving top-down sustainability instructions, workers would be active components of the knowledge network, and talent management would serve as the catalyst of such activity (

Greene, 2020).

Z. Khan et al. (

2019) identified that the talent development programs contribute to the willingness to share environmental knowledge among employees by creating the sense of purpose and communal shared responsibility.

Li et al. (

2023) also found that organizations that have healthy talent retention and engagement policies establish psychologically safe environments that promote free discussion of sustainability-related matters. As stressed by

Alkhozaim et al. (

2024), even in cases where employees feel that their growth and skills are being invested in, they tend to respond in kind by proactively exchanging green knowledge and ideas. In a similar manner,

Juniarti et al. (

2024), established the fact that leadership-based talent practices enhance the internal communication channel thus ensuring that environmental knowledge flow occurs horizontally.

Rubel et al. (

2021) proved that HR systems with a green orientation based on talent strategies have a direct positive impact on knowledge-sharing behavior reflecting ecological objectives. In line with this,

Abdelhamied et al. (

2023) demonstrated that talent empowerment and recognition contribute to voluntary green knowledge sharing between existing workers within an industry in the context of a sustainability transition. Based on the line of thinking, the following hypothesis is postulated:

H2. Talent management has a significant positive effect on green knowledge sharing.

2.5. Talent Management and Green Employee Voice

In order to have green employee voice, more than just awareness is needed; employees should be psychologically safe, feel valued and have the power to speak up with suggestions, concerns, or ideas to enhance environmental performance (

Gaafar et al., 2021). Talent management is a pillar mechanism towards the development of such an environment. With the help of investment in the provisions which foster the encouragement of the recognition, participation, and developmental growth of their employees, the organization demonstrates the employees that their views are not only welcome but that they can make a difference as well (

Shan & Wang, 2024). Specifically, the phenomenon is applicable to tourism and hospitality settings where frontline personnel have the potential to be the ultimate firsthand experience regarding sustainability issues and operational shortcomings (

Meng et al., 2024). An appropriate form of talent management such as one that emphasizes inclusivity in managing and culture of transparent communication and shared environmental values also boosts employee readiness to contribute green ideas. Notably, such voice behavior does not occur automatically; it is cultivated by the repetitive process of organizational reinforcement and trust-building mechanisms that are instilled in talent systems. In such a way, talent management does not only accompany green employee voice as a background activity but rather actively facilitates it to open an environmentally relevant behavioral channel to innovation (

ud Din & Khan, 2025;

Adamsen & Swailes, 2019). The evidence provided by

Gaafar et al. (

2021) showed that engaged employees are more secure and tempted to share ideas and concerns associated with environmental improvement when employees are engaged strategically through talent initiatives. According to

Oladimeji et al. (

2023), a talent development and supportive leadership that promotes psychological safety is a precondition to engaging in the environmentally powered voice behaviors. Similarly,

Hosseini et al. (

2022) established that talent-oriented HRM systems can establish participatory systems that invite their employees to voice concerns related to sustainability efforts and to drive change.

Holland et al. (

2019) noted that the best practice involves aligning talent strategies to the values of the environment because in such alignment, intrinsic motivation and a sense of responsibility are encouraged among employees to make green suggestions. To supplement these observations,

Alkhozaim et al. (

2024) exemplified the fact that investment in talent does not only develop technical capacity but also enhances the employee interest in being a part of the environmental discourse hence solidifying green voice as one of the strategic consequences of effective talent management. In that sense, the following hypothesis is developed:

H3. Talent management has a significant positive effect on green employee voice.

2.6. Green Knowledge Sharing and Organizational Sustainability

Organizations that aim at sustainability consider knowledge as a tool and not a resource; it is strategic and transformative (

Zada et al., 2025). Green sharing that can be thought of as the means of sharing environmentally relevant ideas, practices, and innovations with the employees in question serves as an essential introduction avenue wherein the sustainability goals are actualized and propagated throughout the organizational hierarchy (

Rasheed et al., 2025). There is a particular need in the tourism and hospitality sector to have timely and voluntary knowledge sharing because such an industry requires fast decision-making, services on-site, and cooperation across functions (

Al-Husain et al., 2025). As workers participate in sharing green knowledge, they can help in learning loops, counter-act repetition in sustainability, and speed up adaptation in organizations to the environment. It develops a shared ecological consciousness and allows personal awareness to transform into organizational capability (

Marjerison et al., 2022). Instead of completely relying on the information provided top-down, sustainability is transformed into an emergent, positive-feedback action of direct communication and interventions between environmentally active employees (

Moxen & Strachan, 2017). It is in this respect that green knowledge sharing is central to defining the extent and magnitude of how well and profoundly sustainability as a concept is part and parcel of organizational life (

Chang & Hung, 2021).

Abbas and Khan (

2023) identified the active flows of environmental knowledge in an organization to create a type of collective ecological awareness and promote more consistent sustainability policies across the departments.

Chang and Hung (

2021) highlighted the importance of organizations that develop the culture of green knowledge sharing to incorporate sustainable actions and achieve better positions to respond to new regulations and incorporate environmental issues into their strategies. Likewise,

Rasheed et al. (

2025) found that green knowledge sharing plays the role of a behavior change driver that allows employees to convert sustainability values into tangible operational practices. An early indicator of internal knowledge exchange on environmental issues gives significant contribution in long-term performance of an organization in terms of innovation and minimizing environmental risk (

Lin & Chen, 2017). Those previous observations have been supported by the findings of

Polas et al. (

2023) who concluded that organizations that institutionalize green knowledge flows are more likely to experience high degrees of employee engagement, environmental responsiveness, and attain higher integration with sustainability aims. Based on this argument the following hypothesis is put forward:

H4. Green knowledge sharing has a significant positive effect on organizational sustainability.

2.7. Green Employee Voice and Organizational Sustainability

Strategies and structures do not imply that organizations can develop any kind of sustainability as it is also influenced by the voices that grow inside. Green employee voice is a bottom-up force that is essential to allowing organizations to unmask blind spots, to build on environmental policies, and to come up with innovative ideas to solve the problem of sustainability (

Gaafar et al., 2021). By voicing their ideas, observations, or concerns on ecological performance voluntarily, however, employees give organizations access to experiential knowledge that would otherwise be overlooked by the management (

Paillé et al., 2023). The value of this is specifically important in tourism and hospitality environments where it is employees who work most closely with both guests and the physical environment which provided them with special insights into the sustainable service practices (

Chen, 2022). Notably, the green employee voice leads to not only the effective improvement of the operations but also the establishment of a participatory and ethically based organizational culture (

Hu et al., 2025). Through open communication and lifting the ability of employees to collaboratively design environmental efforts, companies have the potential to integrate sustainability in the decision-making criteria and in the core strategy of the business. Therefore, green employee voice is not just an assisting phenomenon; it is an empowering trend which is actively working on the way sustainability is perceived, sought, and realized (

Gaafar et al., 2021).

The researchers also showed that by establishing a corporate culture of supporting environmental learning, environmental inputs, and concerns of their employees, organizations become more dynamic and flexible to sustainability demands (

Paulet et al., 2021).

Gaafar et al. (

2021) confirmed this opinion by demonstrating that green voice positively affects internal innovation, especially when the workforce has a feeling of empowerment in recommending eco-efficient changes. Additionally,

Naqvi (

2020) also stressed that employee voice supports the determination of inefficiencies in the functioning of the organization and environmental risks to implement proactive sustainability practice in the organization. According to the study by

Čiarnienė et al. (

2021), organizations which effectively listen to the green suggestions made by their employees tend to score better on the environmental indicators because of higher internal consistency and involvement. On the same note, the work by

Aloqaily (

2023) corroborated that the impacts of green voice include enhancing environmental accountability and communal responsibility culture in any given sector, particularly the dynamic industries such as tourism and hospitality.

Nazeer et al. (

2025) offered the evidence that when the institution of voice mechanism becomes generalized in the organization, it leads to more inclusive and sustainable decisions. In addition,

Yang et al. (

2025) found that, besides the positive effects on transparency, green employee voice leads to strategic agility in achieving the implementation of long-term sustainability objectives. It is based on this view that the following hypothesis is set forth:

H5. Green employee voice has a significant positive effect on organizational sustainability.

2.8. The Mediating Role of Green Knowledge Sharing

Although talent management creates a structural as well as psychological basis of employee engagement, it does not necessarily lead to sustainability in an organization. Most of its effectiveness can be executed by behavioral channels, which interpret strategic purpose into real practice (

Karim et al., 2025;

Taylor, 2018). Among such pathways is green knowledge sharing, which qualifies to be a responsive tool through which the values, skills, and environmental awareness developed by the talent management is shared and implemented throughout the organization (

Al-Romeedy, 2023b). When talent-focused practices are used to support, develop, and empower employees, they will be more inclined to engage in collaborative behaviors, which will enhance sustainability-oriented thinking (

Cascio & Aguinis, 2024). Since the green knowledge is horizontally and vertically volleyed in the organization, it leads to a common perception that the environmental issues combat the initiation of joint efforts. In addition to impressing sustainability on routine behaviors, this procedure also enhances communal responsibility (

Martínez Falcó et al., 2024;

Ullah et al., 2025). Such an alignment in the case of green knowledge sharing translates to one of the crucial behavior bridges between talents developed through talent management as a part of the organization-wide sustainability goal (

Mujtaba & Mubarik, 2022;

Al-Husain et al., 2025). To this end, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6. Green knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between talent management and organizational sustainability.

2.9. The Mediating Role of Green Employee Voice

Incorporating talent management, organizations ensure that it will develop a highly skilled and dedicated workforce that is not only more eco-conscious, but also engaged (

Al-Romeedy & Alharethi, 2024b). Nonetheless, the effect of talent management on the sustainability of the organization is usually offset by the level of empowerment given to the employees to express their environmental worries, knowledge, and ideas (

Adamsen & Swailes, 2019). Employee voice is also considered to be a beneficial behavioral outcome of any inclusive and empowering talent system, with those that promote involvement and allows the freedom of action, and those that generate a healthy sense of psychological safety (

Gaafar et al., 2021). In tourism and hospitality settings with frequently changing operational realities and the emergence of sustainability issues at the ground level, employee voice can be regarded as one of the primary vehicles of adaptive learning and ongoing improvement (

Kirillova et al., 2025). When talent management is conducted in a way that employees are appreciated and supported, they will be more willing to raise their voices on sustainability matters, question the existence of inefficient operating practices, and offer suggestions that resonate with the organization in terms of environment (

Adegoke et al., 2024). This green voice is voluntary, which should be viewed as a mechanism by which the strategic investments in talent are transformed into those behaviors that become actionable and have effects of improving sustainability (

Dan et al., 2021). In such a way, green employee voice mediates the bridge between the motivational impact of talent management and the strategic achievement of sustainability (

Gaafar et al., 2021;

Alkhozaim et al., 2024;

Bhushan & Singh, 2024). Based on this argument, the following hypothesis is postulated:

H7. Green employee voice mediates the relationship between talent management and organizational sustainability.

3. Methodology

The present research focuses on the impact of talent management (TM) on organizational sustainability (OS) in hospitality enterprises and the mediating role of green knowledge sharing (GKS) and green employee voice (GEV). This was based on the conceptual framework developed after extensively reviewing previous empirical studies to establish the theoretical relationships between these constructs. Data will be gathered via a structured survey questionnaire targeted at hotel employees five-star hotels in the Eastern Region, Saudi Arabia. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) will be used to assess the measurement and structural models robustly in testing both the moderating and serial effects. Moreover, statistical measures to identify and manage common method bias (CMB) will also be used to increase the validity of the current findings. The following sections provide a detailed description of the methodology used in the current empirical study.

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

A purposive sample selection was carried out by researchers by selecting the Saudi Arabian Hotel employees of the five-star hotels employed in the Eastern Region.

The study concentrated specifically on frontline employees who work in five-star hotels, particularly those who work at the front-office, food and beverage, and housekeeping departments. These cohorts were identified because they represent the most visible point of contact between the hotel and its clientele where their perceptions and behaviors directly impact service delivery, environmental stewardship, and the overall guest experience. Furthermore, frontline employees have a greater role in the actual operationalization of green practices, which makes their views especially relevant to the explanation of variations in green knowledge and commitment. The five-star hotel category was chosen based on their prominence in the regional hospitality industry as such hotels represent the upper service-level and are generally considered to be the key determinants of service quality, patron satisfaction, and staff output. The Eastern Region was chosen because of its position as one of the most prominent tourist and business destinations in Saudi Arabia, with a high density of the luxury hotels serving the international and domestic markets. Therefore, this area provides a relevant backdrop of exploring the perceptions of hospitality employees.

The hotels in Saudi Arabia are usually categorized in terms of one- to five-star; thus, the current research specifically focused on the category of five-star hotels which are the top category in terms of international and national classification. The sample consisted of ten five-star hotels out of sixteen that are available in the Eastern Region, which collectively is a significant percentage of the total number of five-star hotels operating in the region. This choice hence makes the results of the study more representative to the luxury hotel industry.

The survey was designed as a cross-section survey that was conducted between March and June in 2025. The research methodology involved the use of online surveying methods of distributing and collecting study data. The survey methodology used in administration of the online survey technique was that of

Hair et al. (

2010). Once the instrument had been developed, an online questionnaire was designed and thoroughly scrutinized regarding accuracy and format after which the participants were sent an e-mail providing them with the e-survey link. The objectives of the present study have been delineated in the introductory section, and the hotel employees have been requested to be a part of the study. The participants were made aware of the confidential nature of the research and intended purpose. The introduction and link to e-survey (in both Arabic and English) was sent through numerous common social media accounts (LinkedIn, Facebook, X) to employees working in hotels in the Eastern Region. Each response was discussed several times every day. After the introduction, the researchers provided their contact details in case the participants required additional questions. To ensure that the right ethical standards were met, the participants were adequately informed on the purpose of the study. The participants verbally consented to the use of questions in the quantitative section and were assured that the responses would be kept anonymous. The research team used affiliation and networking, including relatives and colleagues, to identify respondents. Every respondent consented that the data was to be collected as part of the research and that their involvement was entirely voluntary.

3.2. Research Instruments

The study questionnaire followed five broad sections. The demographic and professional details of the respondents were gathered in the first part. The second part gauged talent management (TM) with a 15-item scale based on

Olaka et al. (

2018). In the

Section 3, green knowledge sharing (GKS) based on a six-item scale by

Yu et al. (

2022) was measured. The

Section 4 measured green employee voice (GEV) and consisted of a three-item scale followed by

Gaafar et al. (

2021). The last area assessed organizational sustainability (OS) through an eight-item scale created by

Lee and Ha-Brookshire (

2017). Content validity of the instrument was assessed by eleven academic experts who observed that the instrument is clear and relevant. The seven-point Likert scale was used for all constructs (1, strongly disagree; 7, strongly agree).

3.3. Data Evaluation

The designed research questionnaires were directly sent to 300 full-time workers in a five-star hotel. 268 out of 300 questionnaires were distributed, and a remarkable 89.3% of them were successfully completed. Moreover, there was no missing data. Considering

Nunnally and Bernstein’s (

1994) criterion for maintaining a sample ratio (1:10 items), the sample size of 268 valid replies was appropriate. Among the 268 valid responses, 215 of respondents, representing 80.2%, were male, and 53 of respondents, reflecting 19.8%, were female. Most responses (79.3%) were from employees between the ages of 26 and 35 years, as well as (87.2%) of them being well-informed about hotel green practices.

The current research utilized SPSS version 24 to process the research data. The step-two procedure of analytical process given by

Leguina (

2015) resulted in an analytical process with multiple regression and descriptive analysis via Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) using smart-PLS V4. According to

Henseler et al. (

2009), the extensive use of PLS-SEM can be explained by the fact that it has been used in exploratory and prediction-oriented research. This method supports any sample size and flexible distribution requirements of normality (

Hair et al., 2017;

Do Valle & Assaker, 2016). To mitigate common method variance (CMV), the study employed the Harman test according to

Podsakoff et al. (

2003).

4. Results

To evaluate the possible impact of common method variance (CMV), an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was administered to the 32 items. These findings revealed that the first factor was not rotated and that only a small amount of 29% of total variance was explained, clearly lower than the 50% threshold, which means that in the current research, CMV is likely not an issue of concern (

Podsakoff et al., 2003). To better assess the psychometric properties of the measurement model, the convergent validity and internal consistency reliability were assessed via the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Reliability (CR), and Cronbach alpha tests (see

Table 1). Based on the recommendations of

Hair et al. (

2017), it is recommended that AVE should be greater than 0.50, CR should be greater than 0.70, and standardized outer loading should also be greater than 0.70. The results indicated that every construct met the AVE and CR criteria, meaning that each construct accounts for more than 50% of variance in group of indicators associated with the construct while indicating excellent internal consistency. Moreover, the outer loadings of all items exceeded the thresholds of 0.70, indicating a strong reliability of items. Values of VIF of all indicators were lower than 5, which shows that multicollinearity is not a problem. Both the measurement model and the overall psychometric quality thus appeared to be high in terms of convergent validity and able to meet the recommended standards in the PLS-SEM literature (

Hair et al., 2017;

Henseler et al., 2009).

The results given in

Table 2 demonstrate that each of the variables in the proposed model more accurately reflects the variation in component parts than other components in accordance with the suggestions given by

Hair et al. (

2017) and

Fornell and Larcker (

1981). Thus, discriminant validity of the study model is confirmed. Moreover, all the items of the proposed research model are heavier on their respective constructs than the variable constructs. These results also support the discriminant validity of the model that was established by

Chin (

1998).

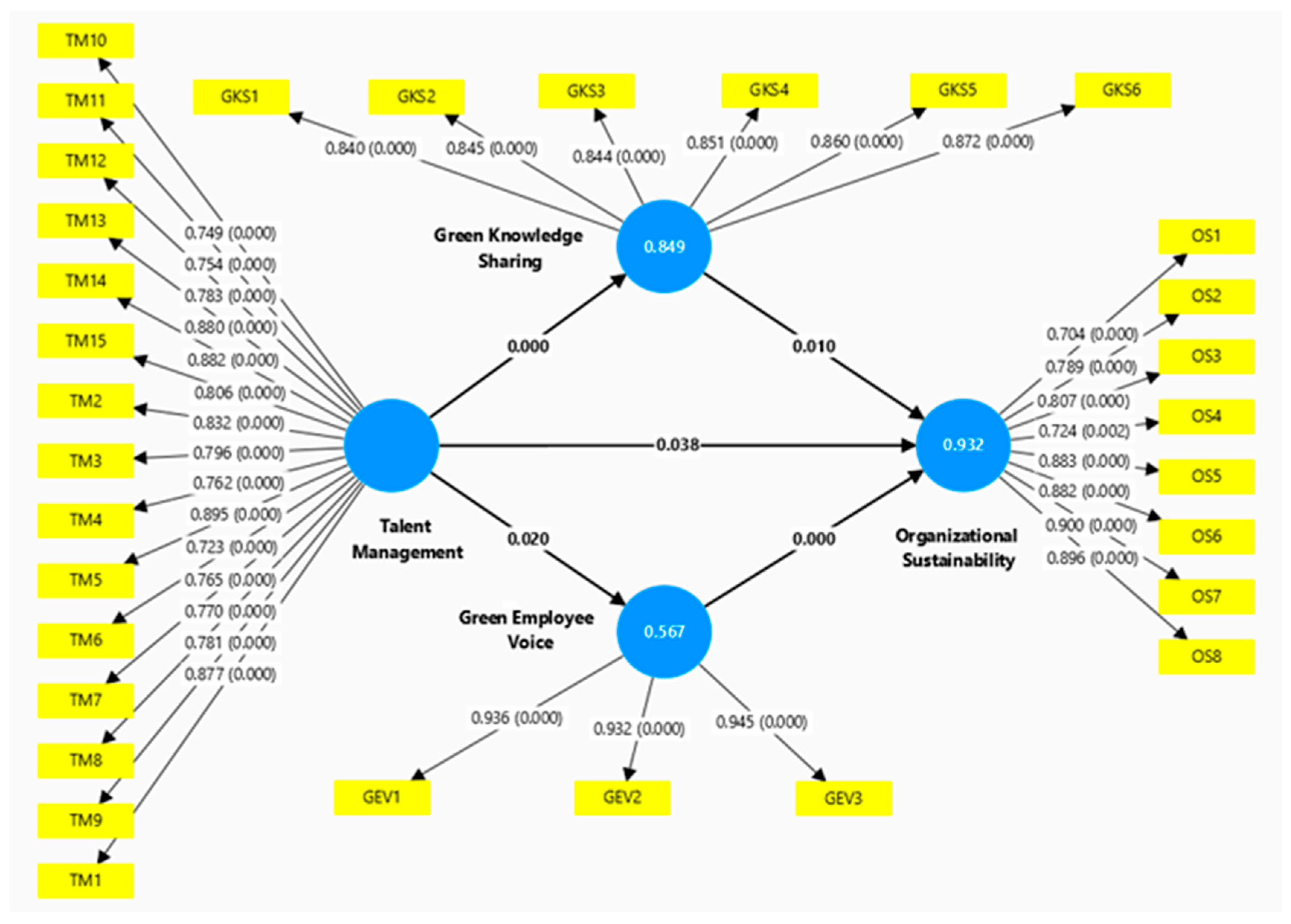

As revealed in

Table 3 and

Figure 2, the results indicated significant and direct relationships between key constructs as supported by the proposed model. The first hypothesis (H1) assumed a direct effect of talent management (TM) on organizational sustainability (OS), which has received support (β = 0.212, T = 2.072,

p = 0.038); this implies that work on the effective TM practices has a direct ability to foster organizational sustainability outcomes, by ensuring that efficiently trained, motivated, and well-managed employees can help realize the environmental goals. The second hypothesis (H2) indicated that a significant correlation existed between TM and green knowledge sharing (GKS) (β = 0.922, T = 5.728,

p < 0.001) and has proved that robust TM systems will provide an environment where employees are more comfortable and capable of sharing sustainability-related knowledge, hence enhancing green capabilities of the organization. The third hypothesis (H3) associating TM with employee voice (GEV) was also confirmed (β = 0.753, T = 2.336,

p = 0.020), indicating that when an organization has well-established TM frameworks, it is in a position of empowering the employees and enabling them to share their green concerns, suggestions, and ideas to contribute to the green agenda of the organization. The fourth hypothesis (H4) supported that GKS has a positive effect on OS (β = 0.439, T = 2.571,

p = 0.010); it is indicated that active sharing of environmental knowledge among employees is crucial in integrating sustainable procedures into the daily practice. Similarly, the fifth hypothesis (H5) revealed that GEV has a substantial positive impact on OS (β = 0.364, T = 3.844,

p < 0.001), which validates the assumption that by allowing the employees to raise their voices and express their ideas and concerns related to sustainability, the organization would be able to increase the level of its sustainability performance (see

Figure 2).

Indirect relationship findings shed more light on the mechanism(s) by which TM is related to OS. The sixth hypothesis (H6) showed that GKS partially mediates (β = 0.404, T = 2.860, p = 0.004) the association between TM and OS significantly, suggesting that the impact of TM on sustainability is strengthened when the employees actively share environmental knowledge to help the organization develop shared expertise and hasten a sustainable practice adoption. In addition, the seventh hypothesis (H7) revealed that GEV turns out to partially mediate the connection between TM and OS (126, T = 2.050, p = 0.040), indicating that the influence of TM on sustainability is stronger when employees are encouraged to vocalize their perspectives regarding environmental issues and propose practical improvements. The combination of these results suggests that, on the one hand, TM is another tool that can directly increase sustainability performance; on the other hand, it works best when it is entrenched in the channels of knowledge sharing among employees and pro-environmental action as part of a culture of participatory and innovation-negative sustainability.

5. Discussion

Based on the results and the theoretical and empirical backgrounds discussed, it is clear that the talent management is a substantial cornerstone that fosters the sustainability of the whole organization, and the mediating processes are green knowledge sharing and green employee voice. The associations made in the current research validate the behavioral and cognitive channels through which human resource techniques have a role to play in tourism and hospitality organizations sustainability. These findings are further elucidated subsequently, alongside co-relating them to the literature as well as identifying the theoretical and practical implications at large.

The findings were that there is a considerable influence of talent management towards organizational sustainability. This finding is consistent with

Almaaitah et al. (

2020) who stated that talent management has a central role in enhancing organizational sustainability. In a similar manner, the

Al Aina and Atan (

2020) research results have approved the role of talent management in the improvement of organizational sustainability through the alignment of ability levels of employees with long-term job objectives.

Mujtaba and Mubarik (

2022) described the existence of a significantly positive connection between talent management and organizational sustainability which revealed the fact that systematic talent systems facilitate sustainable performance. Similarly,

Sumathi and Sumathi (

2022) emphasized that talent management strengthens the sustainability of the organizations. The significance of this connection was also stressed by

Al-Romeedy (

2023b), who conducted a study in the hospitality industry that demonstrated that talent management also contributes to the organizational sustainability efforts directly. To further corroborate this, it was established that the element of talent management is one of the most determinant factors of organizational sustainability and particularly, one that is used in dynamic service industries (

Tunio et al., 2023). Most recently,

Tunio et al. (

2024) and

Al-Romeedy (

2024) have added empirical evidence of how effective talent management can make organization sustainability thrive due to strategic alignment and capacity development within the organization.

The outcomes also discussed the effectiveness of talent management on green knowledge sharing in a positive way. Such results are corroborated by

Z. Khan et al. (

2019), who showed that talent management projects promote knowledge sharing practices among employees via their favorable participation in the voluntary exchange of environmental knowledge within the company. It was also revealed by

Rubel et al. (

2021) that green knowledge sharing is encouraged through talent management. In a similar manner,

Li et al. (

2023) added that the organizations that have well-developed talent management practices are also more likely to support green knowledge sharing.

Abdelhamied et al. (

2023) established the fact that talent management significantly affects the sharing of green knowledge. This correlation has also been confirmed by

Alkhozaim et al. (

2024), who indicated that there is a contribution to green knowledge sharing by talent management. In agreement with the findings,

Juniarti et al. (

2024) explained that talent management does not only facilitate but also contributes to energizing green knowledge sharing as part of organization learning.

In addition, the findings showed that talent management has great positive impact on the green employee voice. This is corroborated by

Gaafar et al. (

2021) who stated that talent management builds a positive environment in which employees feel free to give environment-centered suggestions and concerns. As shown in

Hosseini et al. (

2022), the optimization of green employee voice by talent management was also evident. Confirming this belief,

Oladimeji et al. (

2023) established that talent management systems anchored in devotion to the workers and their growth could result in a higher readiness over workers to pursue sustainability discussions via green employee voice. As a rule,

Alkhozaim et al. (

2024) obtained empirical data demonstrating that talent management reinforces the green voice of employees.

Moreover, the findings portrayed that green knowledge sharing has a positive influence on organizational sustainability. This observation corresponds with that by

Lin and Chen (

2017) who indicated that a firm must have the green knowledge sharing as one of the factors that facilitate sustainability.

Chang and Hung (

2021) have also discovered that the organizations which encourage the sharing of green knowledge better integrate sustainable approaches in their activities, which yields better environmental results and prolonged resilience. In line with that,

Polas et al. (

2023) emphasized the fact that green knowledge sharing promotes organizational sustainability.

Abbas and Khan (

2023) furthered this connection by evidencing that when the green knowledge is allowed to flow internally, it assists sustainable decision-making and makes the organization more responsive to the environmental issues. Additional support was provided by

Rasheed et al. (

2025) who also reported that green knowledge sharing plays an important role in sustainability of organizations.

Also, it was stated in the results that green employee voice positively contributes to the sustainability of the organization. The same is echoed by

Naqvi (

2020) who discovered that expressing environmental concerns and suggestions have positive results because employees turn into responsive organizations regarding sustainability issues when they actively practice and offer these kinds of sentiments. This was further supported by the green employee voice that positively contributes to the organizational sustainability (

Gaafar et al., 2021). Quality of organizational–environmental adaptation is highly emphasized among employees in their ability to raise concerns when it comes to ecological issues as it facilitates a culture of environmental responsibility (

Čiarnienė et al., 2021). In the same manner,

Paulet et al. (

2021) noted that green employee voice plays a role in sustainability.

Aloqaily (

2023) has shown that this is an important mechanism of behavior because green employee voice is instrumental in the process of sustainability entrenchment in an organization culture and strategy. Also, after the research conducted by

Nazeer et al. (

2025) and

Yang et al. (

2025), the motivation of the green voice of employees is observed to promote resilient and environmentally focused organizations.

Most importantly, the results of findings concluded that green knowledge sharing and green employee voice mediated the connection between the talent management and the sustainability of an organization. This conclusion further supports the idea that the effects of talent management can be considered rather broadly compared to the actual organizational final outcomes, since it operates along particular behavioral and communicative channels. The sharing of green knowledge serves as a process by which the potential and consciousness that have developed through talent management are distributed throughout the organization so that the organization can collectively identify with the goals of sustainability. Meanwhile, green employee voice converts individual dedication into practical conversation to enable employees to take control and formulate their own version of sustainability procedures. These two mediating roles demonstrate the importance of the internal social processes of transferring the strategies related to talent into the measurable impact on sustainability. The above finding confirms that talent-management practices without a culture of open environmental communication and continuous knowledge exchange between toxic and healthy environments are not adequate unless both are competent because they form behavioral bridges in between the capital investment in human capital and organizational sustainable change.

The results indicate that standard human resources practices, such as careful employee selection, competency development through training and job rotation, appropriate placement, and retention activities not only contribute to improved individual and organizational performance but also enhance the transfer of environmental knowledge among employees within the organization. This transfer is an essential tool for achieving long-term organizational sustainability, as it helps establish a more environmentally aware corporate culture and enhances the organization’s ability to adapt to the requirements of sustainable development. In this sense, this finding differs from the approach adopted by high-performance work systems (HPWSs), which focus on intensifying work and productivity. The results of this study confirm the added value of traditional human resources practices in supporting the environmental dimension of organizational sustainability. It is also worth noting that this relationship may be influenced by the specific context in which the study was conducted: five-star hotels within the hospitality sector in the Arab region, where customers are characterized by a relatively high degree of environmental awareness. This awareness is likely to be a factor influencing the strength of the association revealed by the results, which calls for caution when generalizing these results to other sectors or environments with different characteristics.

6. Research Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The results of the current paper can be taken as helpful in enhancing the current state of Social Exchange Theory (SET) by developing it to cover more ground in aspects such as sustainability behavior and strategic human resource management in tourism and hospitality corporate entities. In conventional terms, SET focuses on how people respond to positive treatment in organizations by returning the favor through positive, and usually discretionary, behavior. In this regard, the fact that talent management poses a significant positive impact in terms of organizational sustainability, green knowledge sharing and green employee voice justifies further the prime principle of SET; that is, employees reciprocate what is perceived to be their support and investment and trust in them through positive constructive actions that work to the benefit of the organization. The scope of the study demonstrates that talent management encourages not only general compliance but also sustainability-oriented behaviors. Within the framework of Social Exchange Theory (SET), this does not imply an extension of the theory beyond its traditional scope but rather confirms that employees engage in ecological activities—such as green knowledge sharing and green employee voice—when they perceive these actions as supporting the organization’s primary goals. In the context of hospitality, where customer satisfaction is strongly linked to ecological practices, employees are motivated to contribute to sustainability as part of their reciprocal commitment to the organization.

Further, the positive impact of green knowledge sharing and the green employee voice on organizational sustainability can help us comprehend the behavioral manifestation of reciprocity that occurs under SET. Both processes of proactive behavior are non-prescribed and voluntary, but they occur when the employees feel that the organization is fair, supportive to them, and one to which they relate their values. In the study, such behaviors are projected as critical channels through which the social exchange process can contribute to larger frames of organizational objectives, specifically sustainability. This supports the argument in the sense that employees are not just mere recipients of the HR practices but active contributors to value-co-creation in cases where there is a presence of trust-based relationships.

It is particularly essential to note that the mediating role of green knowledge sharing and green employee voice in the relation of talent management and organizational sustainability offers an exact theoretical mechanism in SET. Based on this reasoning, the link between organizational support (talent management) and organizational outcomes (sustainability) is not direct but mediated through employees’ choices to engage in behaviors that they perceive as beneficial to both themselves and the organization. In this study, such “win-win” behaviors refer primarily to the alignment between employee actions and organizational goals; for example, they align when ecological initiatives are consistent with customer expectations or cost-saving strategies. This mediating effect demonstrates that the SET exchanges are not limited to a dyadic relationship (individual–organization) but can also take place at a collective level, being embedded in shared knowledge systems and organizational cultures of voice that amplify the sustainability outcomes. In this sense, the contribution of the study is not to extend SET beyond its scope, but to illustrate how positive organizational practices encourage employees to interpret and enact their obligations in ways that serve both organizational performance and broader sustainability objectives when these are supported by company policies and procedures. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge an alternative perspective suggested in the literature and reflected in the reviewer’s concern. From this view, the ecological actions of employees may not stem solely from their discretionary reciprocity but are often contingent on company policies and procedures. In other words, employees engage in green knowledge sharing or green voice primarily when organizational strategies (such as customer satisfaction or cost-saving initiatives) clearly support such behaviors. This nuance suggests that the explanatory power of SET in this context depends on how organizational goals frame the meaning and value of pro-environmental behaviors.

Lastly, this research contributes to the advancement of SET in the sense that not only is SET relevant in sustainability discourse, but it also reveals how employee behaviors mediate the transitional processes between organizational inputs and strategic outputs; the extent of this mediation is fine indeed. It provides empirical evidence to the application of SET in green organizational behavior and creates a hurdle to the speculative research in future on how psychological contracts and perceived organizational support are manifested within the environmental context.

6.2. Practical Implications

The results of the research propose several feasible implications in tourism and hospitality organizations in terms of improving their sustainability performance by engaging in the strategic investment of human capital. To begin with, organizations are advised to learn not to undermine talent management as a pillar to organizational sustainability with regard to not only enhancing performance of the employees but also inculcating lasting environmental principles within the organizational culture. This needs drawing and adopting integrated talent management systems in the alignment of the respective recruitment, development, and retention strategies with sustainability purposes. To develop the workforce that could act sustainably and feel committed to sustainable action, it is important to integrate sustainability competency into training plans and performance review. Sustainability competency may include systems thinking, environmental awareness, and innovation, among others.

Second, the study enhances nurturing of green knowledge sharing as a necessary internal capacity. To promote this, leaders ought to think of formalizing both informal and formal platforms to share environmental knowledge, such as cross-functional sustainability workshops, peer learning circles, and online knowledge platforms. However, it is important to highlight that the most influential channel available to managers is not limited to knowledge-sharing platforms but lies in the way operating procedures are designed and implemented. When ecological content is embedded directly into operating procedures—such as in standard workflows, service delivery protocols, and decision-making guidelines—and when these changes are clearly justified in terms of their environmental benefits, their weight and impact on organizational behavior are considerably stronger than if ecological information is communicated only through voluntary knowledge-sharing activities. In addition, reward and recognition systems should be adjusted so that not only task performance is rewarded but also behaviors relevant to knowledge sharing that ultimately contribute to achieving sustainability objectives. This alignment between operating procedures, knowledge-sharing practices, and reward systems ensures that sustainability is integrated into both the formal and informal dimensions of organizational life. This also encompasses the encouragement of open dialogue and the reduction in hierarchical disparities, thereby fostering a psychologically safe environment in which employees are better positioned to contribute eco-relevant knowledge.

Third, green employee voice was found to have a positive impact on sustainability outcomes, and so a culture of expressive employee empowerment needs to be developed deliberately. Companies should not rely on offer boxes, but instead they need to incorporate environmental voice into strategy deliberations. This may involve the formation of green committees, the regular hosting of a green sustainability forum and employee integration in the development of green projects. They should train managers to listen actively, give constructive replies, and act on employee feedback regarding environmental enhancement thus strengthening the element of trust and proving the worth of employees in stimulating sustainable change. Lastly, the mediating effect of green knowledge sharing and green employee voice indicates that talent management should be accompanied by some employee engagement activation mechanisms. To encourage these behaviors, talent strategies must be premeditated such that empowerment, transparency, and inclusion are pursued. Pro-environmental leadership at all levels should be driven by role modeling of behaviors, giving a clear message on the vision of sustainability in which the employees can relate to and become able to contribute to. In that way, an organization can convert the HR functions that are supposed to provide administrative support efforts into enablers of sustainability.

7. Limitations and Future Directions

Similarly to any empirical research, this study has multiple limitations that can be exploited as promising avenues in further research. First, the organizations that were used to collect data were working in the tourism and hospitality industry, which will be suited to the purpose of the study but can decrease the universality of its results when applied to other sectors. Future researchers could implement some cross-industry comparative research, e.g., on manufacturing, healthcare, or education, to ascertain whether the findings apply elsewhere, in other organizational or environmental settings.

Second, the study focused on green knowledge sharing and green employee voice as a mediator, but it did not investigate the possible role of moderating variables, i.e., leadership style, organizational culture, and environmental strategy. The current study can be used as the base of future research that could include moderated mediation models to find out the boundary conditions and to find out whether the discovered effects might be enhanced or attenuated.

Third, the conceptual framework was also anchored in the theory of Social Exchange, which has a good explanatory power; nevertheless, the intricacies involving human and environmental interaction might require the use of more theoretical lenses. Future research interventions may utilize the Theory of Self Determination, the Theory of Institution, or Ability–Motivation–Opportunity (AMO) model to augment on analysis of motivational and situational factors of green behaviors.

Fourth, the study analysis was primarily carried out at individual-level of perceptions and behaviors, thereby excluding any potential effects at group level or the organizational level. Future research is likely to be conducted on a multilevel modeling approach view since it will analyze the involvement of group practices, group dynamics or departmental policies on the interrelationship between talent management and sustainability outcomes.

Fifth, it should be noted that the results obtained may reflect the specificity of the business sector covered by the study, namely luxury (five-star) hotels in the Arab region, where customers are relatively environmentally aware. This context may be a factor influencing the strength of the discovered relationship between HR practices and environmental knowledge transfer. Accordingly, the results cannot be completely generalized to other sectors. Therefore, this study recommends that future research expand on testing this relationship in diverse settings, such as higher education or other service institutions, and compare results across different sectors and levels of environmental awareness. This will help clarify the extent to which these practices impact organizational sustainability.

Sixth, it is also important to note that the interpretation of employees’ eco-friendly behaviors as an outcome of talent management practices should be treated with caution. Such behaviors may not solely arise from employees’ discretionary reciprocity but are often contingent upon organizational policies and strategic priorities. In other words, ecological actions such as green knowledge sharing or green voice are more likely to occur when company procedures and objectives (e.g., customer satisfaction or cost-saving strategies) explicitly support them. Future research could therefore further examine how different organizational policies shape the extent to which HRM practices translate into sustainability-oriented behaviors.

8. Conclusions

The study aimed to investigate the role of practicing talent management (TM) in enhancing the organizational sustainability (OS) within the tourism and hospitality industry with special consideration given to the mediating processes of green knowledge sharing (GKS) and green employee voice (GEV). The results reveal that TM has a significant indirect influence on OS via GKS and GEV, and it is essential to encourage the culture of collaboration and environment-saving atmosphere in the workplace. Within these mediators, GKS came out as a specific influential aspect, indicating that the systematic transfer of green-related skills and practices between the employees is essential in the translation of talents abilities into sustainable results. GEV also played a pivotal role since it is vital to empower the employees to express and champion the eco-friendly initiatives, hence consolidating the sustainability agenda.

These findings validate the strategic nature of incorporating green-oriented knowledge systems and participative communication systems as part of the human resource strategies on tourism and hospitality entities. In the specific context of the Eastern Region of Saudi Arabia, where luxury five-star hotels dominate the hospitality landscape and serve both international and domestic markets, the results highlight how TM practices can be effectively leveraged to reinforce sustainability objectives. The prominence of frontline employees in customer-facing roles in this region further emphasizes the practical value of fostering GKS and GEV to enhance service quality, environmental stewardship, and guest satisfaction. Nevertheless, it is possible that TM has a different impact on sustainability based on the size of organization, organizational culture, and national environmental priorities. Therefore, it is recommended to be careful in the generalization of these findings to the non-Saudi Arabian context since the differences in the characteristic of the labor markets, environmental regulations, and cultural disposition to sustainability might result in different dynamics. Through the lens of Social Exchange Theory, this paper contributes significant knowledge of how TM leads to sustainable organizational performance by exchanging benefits in reciprocal and trust-based organizational environment interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S.A.-R., A.H.S. and E.H.T.; methodology, A.M.H.; software, A.M.H.; validation, A.M.H., B.S.A.-R., A.H.S. and E.H.T.; formal analysis, A.M.H.; investigation B.S.A.-R., A.H.S. and E.H.T.; resources, B.S.A.-R. and A.M.H.; data curation, B.S.A.-R., A.H.S. and E.H.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.H., B.S.A.-R., A.H.S. and E.H.T.; writing—review and editing, A.M.H., B.S.A.-R., A.H.S. and E.H.T.; visualization, A.M.H. and B.S.A.-R.; supervision, A.M.H. and B.S.A.-R.; project administration, A.H.S.; funding acquisition, A.H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, grant number [KFU252880].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Deanship of Scientific Research Ethical Committee, King Faisal University (project number: KFU252880, date of approval: 1 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from researchers who meet the eligibility criteria. Kindly contact the first author privately through e-mail.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acronyms

| SET | Social Exchange Theory |

| TM | Talent Management |

| OS | Organizational Sustainability |

| GKS | Green Knowledge Sharing |

| GEV | Green Employee Voice |

References

- Abbas, J., & Khan, S. (2023). Green knowledge management and organizational green culture: An interaction for organizational green innovation and green performance. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(7), 1852–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamied, H., Elbaz, A., Al-Romeedy, B. S., & Amer, T. (2023). Linking green human resource practices and sustainable performance: The mediating role of job satisfaction and green motivation. Sustainability, 15(6), 4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, K., Brakrim, H., & Alsarhan, F. (2025). Talent management in the hospitality and tourism industry: A French perspective on hospitality small and medium-sized enterprises. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 37(8), 2757–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamsen, B., & Swailes, S. (2019). Managing talent. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Adegoke, A., Oyindamola, K., & Offonabo, N. (2024). The role of HR in sustainability initiatives: A strategic review. International Journal of Research in Engineering, Science and Management, 7(5), 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Al Aina, R., & Atan, T. (2020). The impact of implementing talent management practices on sustainable organizational performance. Sustainability, 12(20), 8372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husain, R. A., Jasim, T. A., Mathew, V., Al-Romeedy, B. S., Khairy, H. A., Mahmoud, H. A., Liu, S., El-Meligy, M. A., & Alsetoohy, O. (2025). Optimizing sustainability performance through digital dynamic capabilities, green knowledge management, and green technology innovation. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 24217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, P., Gan, G., & Asmawi, A. (2025). Strategies for achieving sustainable management of offshore sand mining in Malaysia. Sustainability, 17(4), 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhozaim, S., Alshiha, F., Alnasser, E., & Alshiha, A. (2024). How green performance is affected by green talent management in tourism and hospitality businesses: A mediation model. Sustainability, 16(16), 7093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaaitah, M., Alsafadi, Y., Altahat, S., & Yousfi, A. (2020). The effect of talent management on organizational performance improvement: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Management Science Letters, 10(12), 2937–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloqaily, A. (2023). The effects green human resource on employees’ green voice behaviors towards green innovation. ABAC Journal, 43(4), 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Romeedy, B. S. (2023a). The effect of green organizational culture on environmental citizenship in the Egyptian tourism and hospitality sector: The mediating role of green human resource management. In Global perspectives on green HRM: Highlighting practices across the world (pp. 155–186). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Romeedy, B. S. (2023b). The effect of talent management on performance: Evidence from Egyptian travel agencies. In Managing human resources in Africa: A critical approach (pp. 25–51). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Romeedy, B. S. (2024). Green human resource management and organizational sustainability in airlines—EgyptAir as a case study. In Green human resource management: A view from global south countries (pp. 367–386). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Romeedy, B. S., & Alharethi, T. (2024a). Reimagining sustainability: The power of AI and intellectual capital in shaping the future of tourism and hospitality organizations. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 10(4), 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Romeedy, B. S., & Alharethi, T. (2024b). Sustainable tourism performance through green talent management: The mediating power of green entrepreneurship and climate. Sustainability, 16(22), 9900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Romeedy, B. S., & Alharethi, T. (2025). Leveraging green human resource management for sustainable tourism and hospitality: A mediation model for enhancing green reputation. Discover Sustainability, 6(1), 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Romeedy, B. S., & Singh, A. (2026). Emerging green entrepreneurship: A path to green business models. In Incentives and benefits for adopting green entrepreneurship practices (pp. 79–104). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan, M., & Singh, R. (2024). Talent management facilitates net-zero transition through employee green behavior. In Net zero economy, corporate social responsibility and sustainable value creation: Exploring strategies, drivers, and challenges (pp. 117–129). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Cascio, W., & Aguinis, H. (2024). Applied psychology in talent management. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T., & Hung, C. (2021). How to shape the employees’ organization sustainable green knowledge sharing: Cross-level effect of green organizational identity effect on green management behavior and performance of members. Sustainability, 13(2), 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. (2022). Strategic sustainable service design for creative-cultural hotels: A multi-level and multi-domain view. Local Environment, 27(1), 46–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, Y., & Mohamed, S. (2024). A sustainable collaborative talent management through collaborative intelligence mindset theory: A systematic review. Sage Open, 14(2), 21582440241261851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. (1998). Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly, 22, vii–xvi. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/249674 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Čiarnienė, R., Vienažindienė, M., & Adamonienė, R. (2021). Linking the employee voice to a more sustainable organisation: The case of Lithuania. Engineering Management in Production and Services, 13(2), 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, S., Ivana, D., Zaharie, M., Metz, D., & Drăgan, M. (2021). Digital talent management. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Carrion, R., López-Fernández, M., & Romero-Fernandez, P. (2020). Sustainable human resource management and employee engagement: A holistic assessment instrument. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(4), 1749–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Valle, P. O., & Assaker, G. (2016). Using partial least squares structural equation modeling in tourism research: A review of past research and recommendations for future applications. Journal of Travel Research, 55(6), 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elegbe, J. (2016). Talent management in the developing world: Adopting a global perspective. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaafar, H., Elzek, Y., & Al-Romeedy, B. S. (2021). The effect of green human resource management on green organizational behaviors: Evidence from Egyptian travel agencies. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 10(4), 1339–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]