Travel, Sea Air and (Geo)Tourism in Coastal Southern England

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Modern Geotourism

1.2. Unaware Modern Geotourists

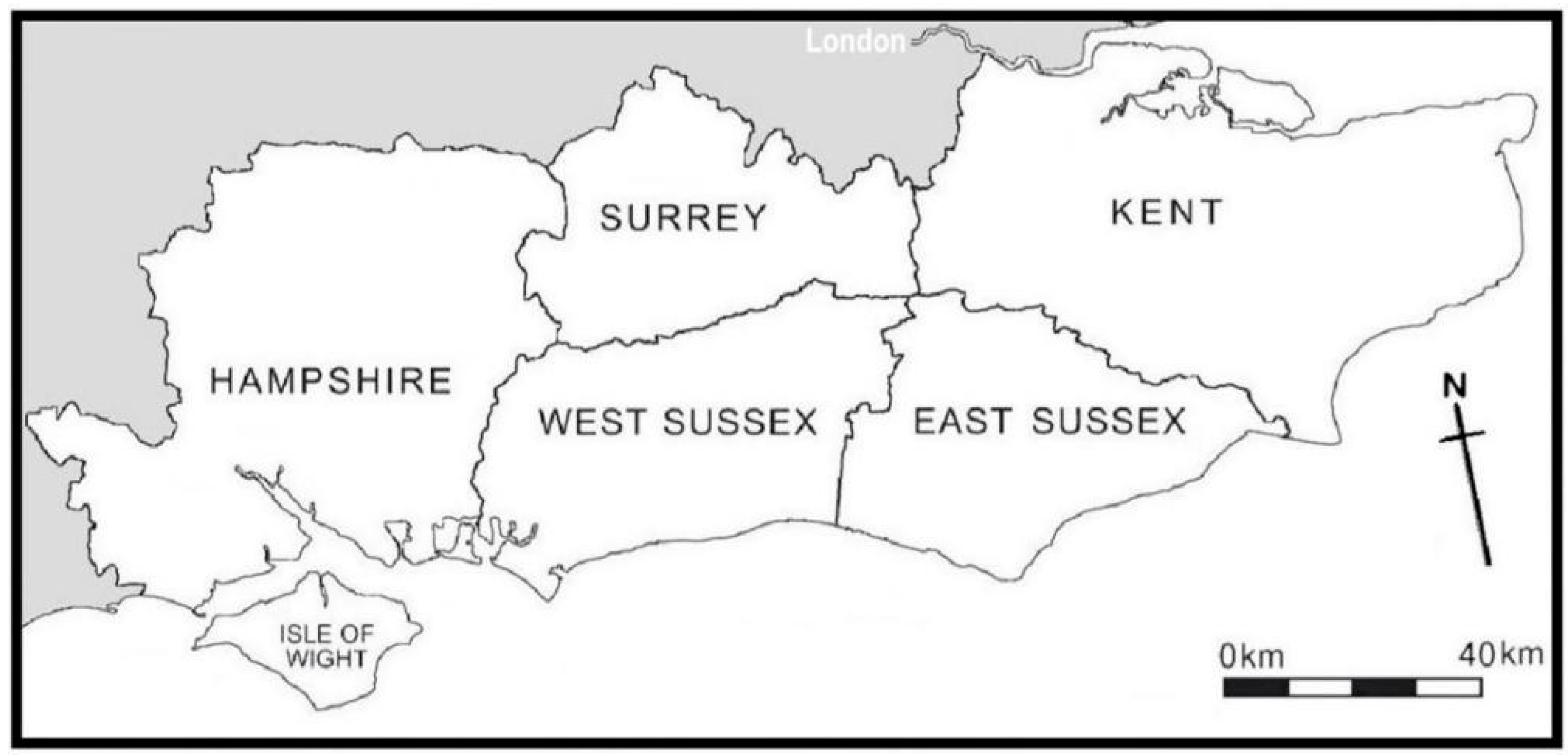

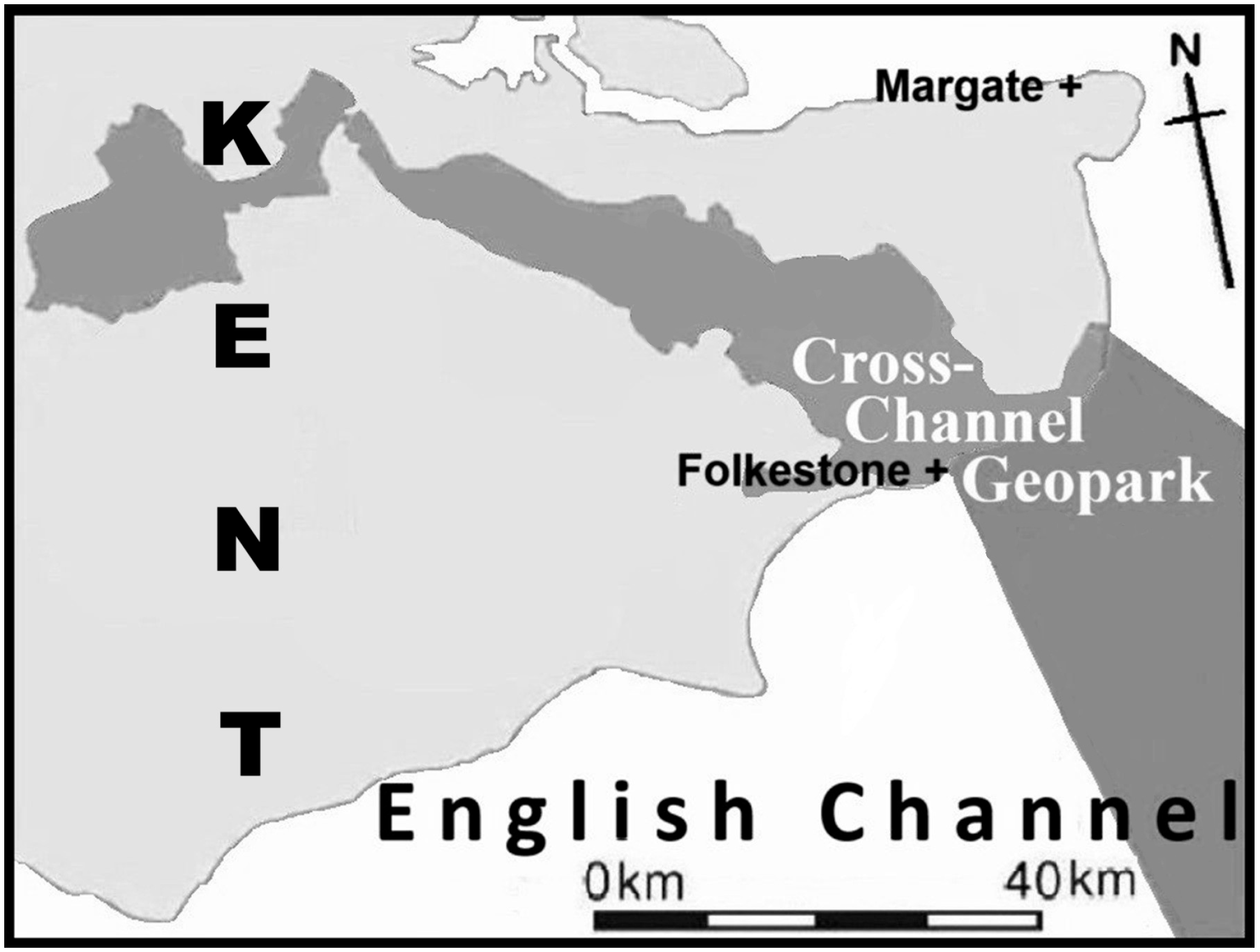

2. Coastal Southern England

2.1. The Region Delineated

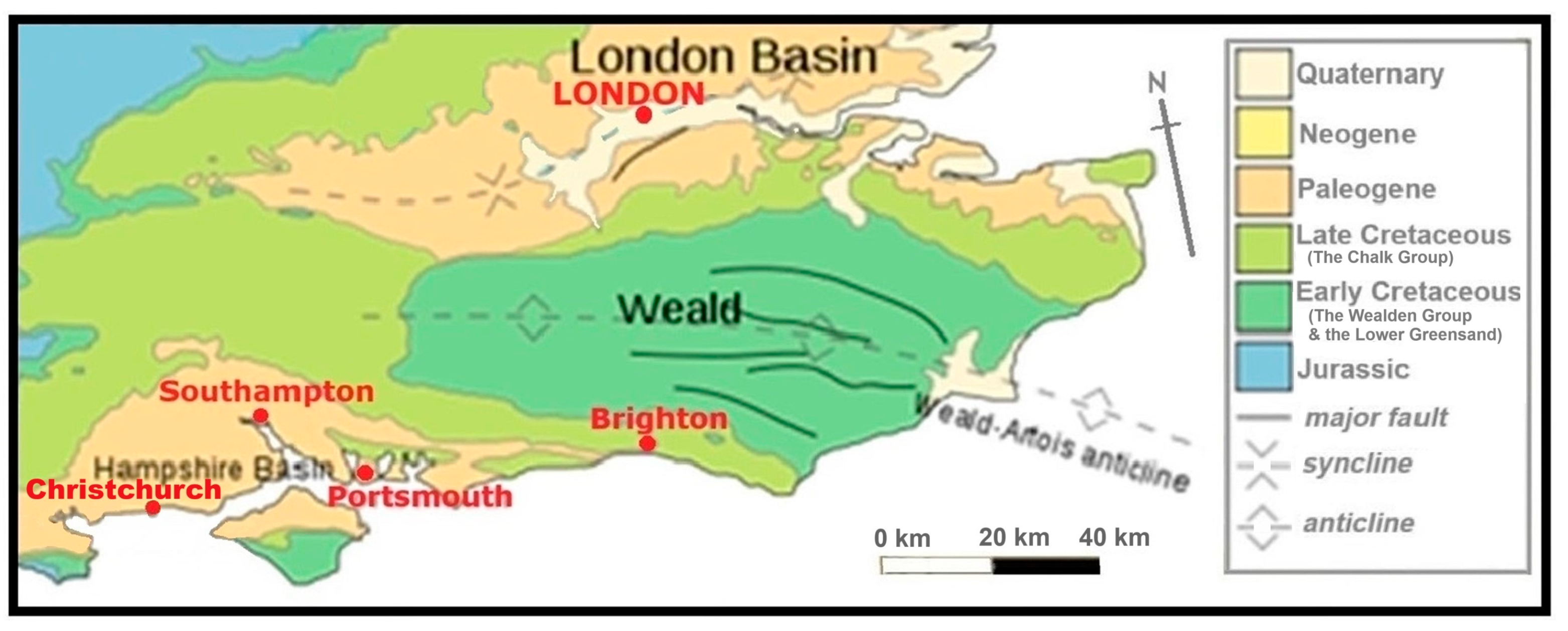

2.2. The Region’s Geology

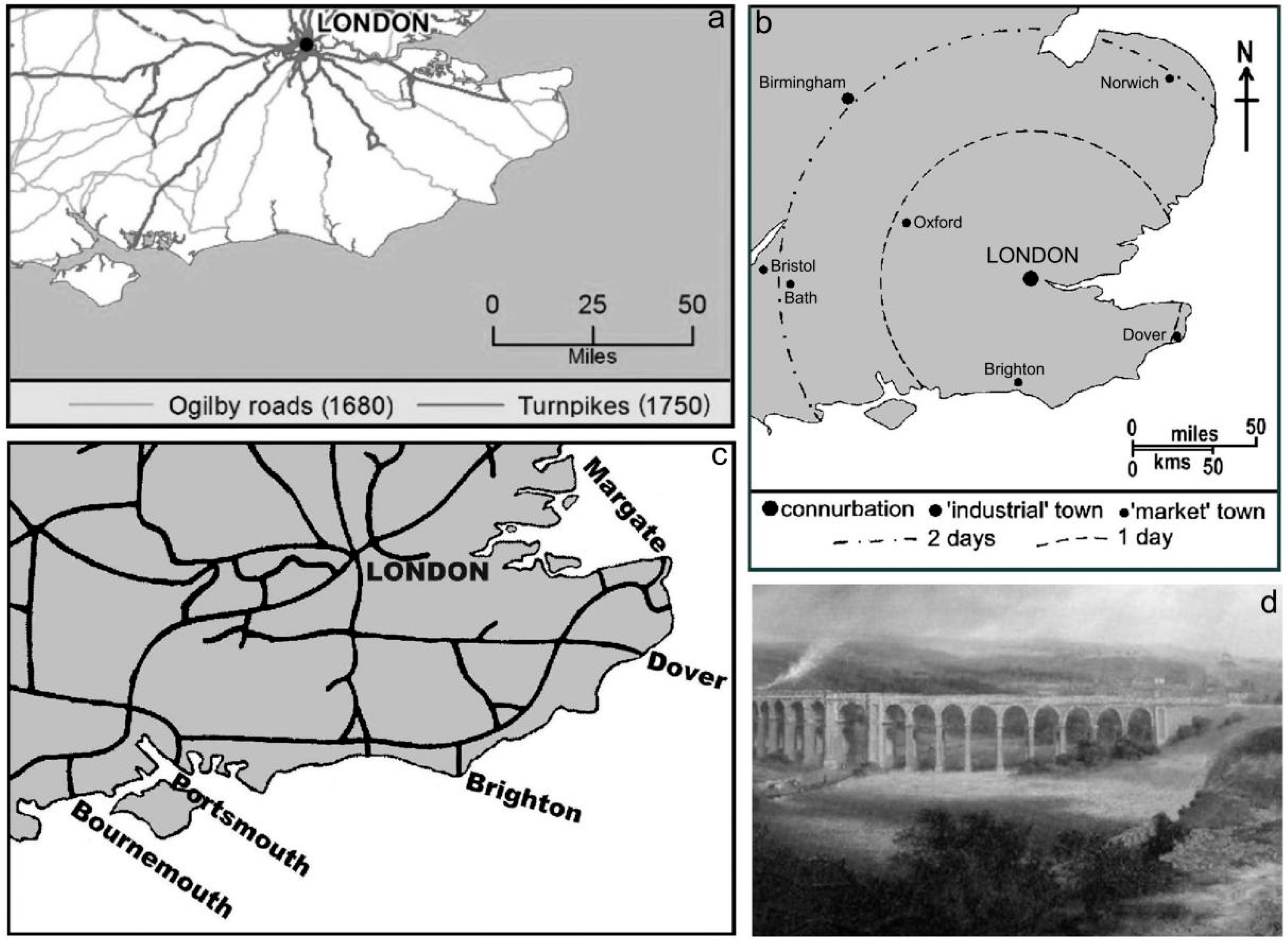

2.3. A Much Visited Region

3. Research Methods and Materials

3.1. The Research Questions

3.2. A Historical Qualitative Approach

3.3. The Literature

3.4. The Artworks

3.5. Fieldwork

3.6. Conceptual Models and Themes

4. The Results

4.1. Leisured Visitors

4.1.1. Early Solo Travellers

4.1.2. Coaching and Railway Travellers

4.2. For Health and Art

4.2.1. Londoner’s Coastal Recuperation

4.2.2. Renowned Painters and Their Landscapes

4.3. Diaries, Travel-Guides and Guidebooks

4.3.1. The Bizarre and a Revolution

4.3.2. Early Travel Literature

4.3.3. Railway Guidebooks

4.3.4. The Guidebook Series

4.3.5. In Summary

4.4. Some Geo-Publications

4.4.1. The London Factor

4.4.2. Geo-Publication Types: Textbooks, Manuals and Field-Guides

4.5. Some Regional Geo-Texts

4.5.1. Some Hampshire, Kent and Surrey Geo-Texts

4.5.2. Some Sussex Geo-Texts

4.5.3. Some Isle of Wight Geo-Texts

4.6. The Historic Literature Analysed

4.7. Some Proposed Geo-Interpretation

Some Current Provision

5. Closing Discussion

5.1. Some Remarks

5.2. The ‘Travellers’ Gaze’

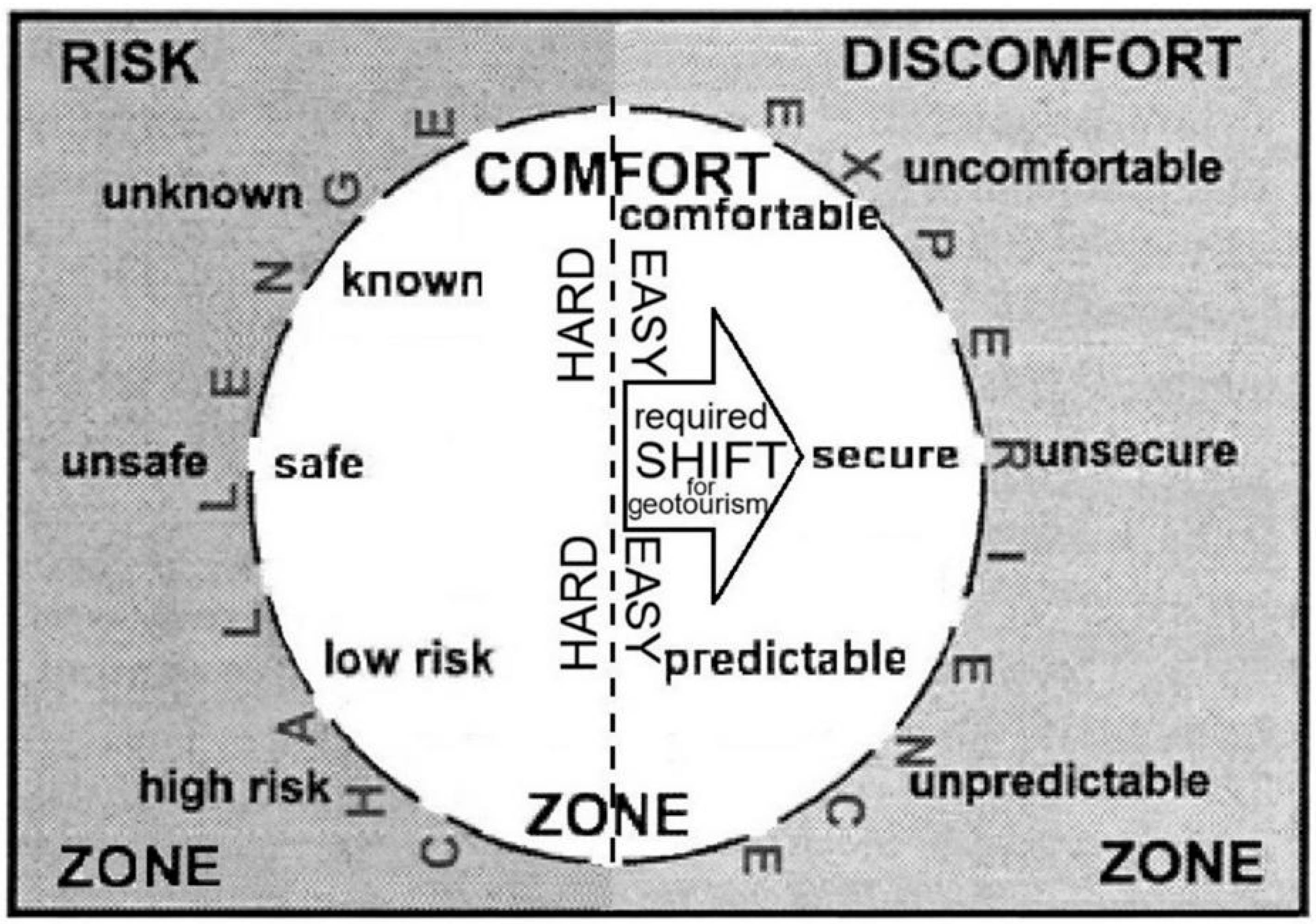

5.3. The ‘Comfort Zone’

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldridge, D. (1993). Site interpretation: A practical guide. Scottish Tourist Board. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, D. E. (1986). The botanists: A history of the botanical society of the British Isles through a hundred and fifty years. St Paul’s Bibliographies. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, D. E. (1994). The naturalist in Britain: A social history (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, C. B. (Ed.). (1934). The Torrington diaries: Containng the tours through England and Wales of the Hon. John Byng (Later fifth viscount of Torrington) between the years 1781 and 1794 (Vol. 1). Eyre & Spottiswoode. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. (1814). The Cambrian tourist, or post-chaise companion through Wales; Being a short but comprehensive description of every object most worthy of attention in the Welch territories with a chart, showing at one view the most eligible route, best inns, distances, and objects (5th ed.). Walker, Edwards, and Reynolds. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. (1832). The Gentlemans magazine and historical chronicle (Vol. 52, p. 45). [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. (1859). Nelson’s hand-book for tourists: The Isle of Wight, with a description of the geology of the island. Nelson. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. (1860). Excursion to Folkestone, April 9th, 1860. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 1, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. (1862). Excursion to Lewes, August 6th, 1862. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 1(8), 274–277. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. (2013). Case study 3C—Hastings, UK. In Arch-Manche: Archaeology, art and coastal heritage—Tools to support the coastal management and climate change planning across the Channel Regional Sea: Technical report. Arch-Manche. [Google Scholar]

- Aslet, C. (2005). Landmarks of Britain: The five hundred places that made our history. Hodder & Stoughton. [Google Scholar]

- Awsiter, J. (1768). Thoughts on Brightelmston. Concerning sea-bathing, and drinking sea-water. With some directions for their use in a letter to a friend. J. Wilkie. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H. A. (1998). Northern Arcadia: Foreign travelers in Scandinavia, 1765–1815. Southern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Binks, G., Dyke, J., & Dagnall, P. (1988). Visitors welcome: A manual on the presentation and in terpretation of archaeological excavations. HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- Black, J. (1993). Italy and the grand tour. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Black, J. (2003). The British abroad: The grand tour in the eighteenth century (2nd ed.). History Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, G. (2014). Bradshaw’s descriptive railway hand-book of Great Britain and Ireland. W.J. Adams [2014 reprint. Glasgow: Harper Collins]. (Original work published 1861). [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, A. (1983). A social history of England. Wiedenfeld & Nicholson. [Google Scholar]

- Bristow, H. W. (1862). The geology of the Isle of Wight. Geological Survey of England & Wales. [Google Scholar]

- Burek, C. V., & Hose, T. A. (2016). The role of local societies in early modern geotourism: A case study of the Chester Society of Natural Science and the Woolhope Naturalists’ field club. In T. A. Hose (Ed.), Appreciating physical landscapes: Three hundred years of geotourism—Special publications, 417 (pp. 95–116). The Geological Society of London. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, E. (1757). A philosophical enquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful. R. and J. Dodsley. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanal, D. (1814). Poems and imitations. Stratford. [Google Scholar]

- Cayla, N., Gauchon, C., & Hoblea, F. (2016). From tourism to geotourism: A few historical cases from the French Alpine Foreeland. In T. A. Hose (Ed.), Appreciating physical landscapes: Three hundred years of geotourism—Special publications, 417 (pp. 199–213). The Geological Society of London. [Google Scholar]

- Cleevely, R. J., & Chapman, S. D. (2000). The two states of Mantell’s Illustrations of the geology of Sussex …; 1827 and c. 1829. Archives of Natural History, 21(1), 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbett, W. (1957). Rural rides (2 volumes). J.M. Dent. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S., Breuer, K., Palmer, S. W., & Blakeslee, B. (2022). How history is made: A student’s guide to reading, writing, and thinking in the discipline. Mavs Open Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conybeare, W. D., & Phillips, W. (1822). Outlines of the geology of England and Wales. William Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, W. B. C. (1808). A new picture of the Isle of Wight, illustrated with thirty-six plates, of the most beautiful and interesting views throughout the island, in imitation of the original sketches, drawn and engraved by William Cooke, to which is prefixed an introductory account of the island, and a voyage around its coast. Vernon, Hood, and Sharpe. [Google Scholar]

- Daiches, D., & Flower, J. (1979). Literary landscapes of the British Isles: A narrative atlas. Paddington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, G. M. (1914). Geological excursions round London. Thomas Murby & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, D. R. (1985). Tennyson and geology. Tennyson Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, D. R. (1999). Gideon Mantell and the discovery of dinosaurs. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deck, A. (1862). Excursion to Hastings. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 1(2), 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Defoe, D. (n.d.). A tour through England and Wales. J.M. Dent. [Google Scholar]

- De la Beche, H. T. (1831). A geological manual. Truetel & Wurtz. [Google Scholar]

- De la Beche, H. T. (1835). How to observe. Charles Knight. [Google Scholar]

- De la Beche, H. T. (1851). The geological observer. Longman, Brown, Green & Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, F. (1850). The geology and fossils of the Cretaceous and Tertiary formations of Sussex. Longman, Brown, Green & Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, F. (1878). The geology of Sussex or the geology and fossils of the Cretaceous and Tertiary formations of Sussex (T. R. Jones, Ed.; 2nd ed.). William J. Smith. [Google Scholar]

- Dowker, G. (1863). Excursion to Herne Bay and Reculver, June 26th, 1863. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 1(10), 339–345. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Duszyński, F., & Migoń, P. (2020). Sandstone landforms of the high weald. In A. Goudie, & P. Migoń (Eds.), Landscapes and landforms of England and Wales (pp. 103–118). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Englefield, H. C. (1816). A description of the principal picturesque beauties, antiquities and geological phenomena of the Isle of Wight. With additional observations on the strata of the Island, and their continuation in the adjacent parts of Dorsetshire by Thomas Webster. Payne & Foss. [Google Scholar]

- Flanders, J. (2006). Consuming passions: Leisure and pleasure in Victorian Britain. Hodder & Stoughton. [Google Scholar]

- Folkestone and Hythe Borough Council. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.folkestoneandhythe.co.uk/stories/geosites-newbie-or-in-the-know/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Freeman, E. F. (1992). The origins of the geologists’ assocation. Archives of Natural History, 19(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, J. (1972). Readability. University of London Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin-Austin, H. H. (1884). Excursion to Guildford and the new railway works in progress there. Saturday, April 26th, 1884. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 8(7), 390–391. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, S. (1972). Past-into-present series: Holidays. B.T. Batsford Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Granville, A. B. (1841). The spas of England and principal sea-bathing places: Southern places (2 volumes). Henry Colbourn. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, F. (2006). Designing the seaside. Reaktion Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Green, C. P. (1989). Excursions in the past: A review of the Field Meeting Reports in the first one hundred volumes of the proceedings. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 100(1), 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardyment, C. (2000). Literary trails: Writers in their landscapes. National Trust Enterprises. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, W. J. (1882). Geology of the counties of England and of North and South Wales. Kelly & Co./Simpkin, Marshall & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, M. H., & Brilha, J. (2017). UNESCO Global Geoparks: A strategy towards global understanding and sustainability. Episodes, 40(4), 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbs, J. (1989). The history of British buse services (2nd ed.). David & Charles. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, W. M. (1842). The book of geology being an elementary treatise on that science to which is appended an account of the geology of English watering-places. R. Tyas. [Google Scholar]

- Highmore, A. (1782). A ramble on the coast of Sussex more than 100 years ago (Hindley, C. (ed.) 1873). Reeves & Turner. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, D. (1985). Constable’s English landscape scenery. John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, T. V., & Sherborn, C. D. (1891). Geologists’ association: A record of excursions made between 1860 and 1890. Stanford. [Google Scholar]

- Horsfield, T. W. (1835). The history and antiquities and topography of the county of Sussex (2 volumes). Sussex Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T. A. (1995). Selling the story of Britain’s stone. Environmental Interpretation, 10(2), 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T. A. (2008). Towards a history of geotourism: Definitions, antecedents and the future. In C. V. Burek, & C. D. Prosser (Eds.), The History of geoconservation. Geological society, special publications, 300 (pp. 37–60). The Geological Society of London. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T. A. (2010). The significance of aesthetic landscape appreciation to modern geotourism provision. In D. Newsome, & R. K. Dowling (Eds.), Geotourism: The tourism of geology and landscape (pp. 13–26). Goodfellow. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T. A. (2012). 3Gs for modern geotourism. Geoheritage, 4(1–2), 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hose, T. A. (2016). Three centuries (1670–1970) of appreciating physical landscapes. In T. A. Hose (Ed.), Appreciating physical landscapes: Three hundred years of geotourism—Special publications, 417 (pp. 1–22). The Geological Society of London. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T. A. (2017). The English Peak District (as a potential geopark): Mining geoheritage and historical geotourism. Acta Geoturistica, 8(2), 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hose, T. A. (2018). Awheel in Edwardian Bedfordshire: A 1905 geologists’ association cycling excursion revisited and contextualised. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 129(6), 748–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hose, T. A. (2021). Historical viewpoints on the geotourism concept in the 21st century. In B. N. Sadry (Ed.), The geotourism industry in the 21st century (pp. 23–92). Apple Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T. A. (2022). Recycling edwardian geology excursions for five modern cyclists’ geotrails in England. Geoconservation Research, 5(1), 209–239. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A., & Jordan, E. (1991). Away for the day; The railway excursion in Britain. 1830 to the present day. Silver Link Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, J. (1967). The story of passenger transport in Britain. Ian Allan. [Google Scholar]

- Kent Downs National Landscape. (n.d.). Available online: https://kentdowns.org.uk/geopark/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Knudson, D. M., Cable, T. T., & Bec k, L. (1995). Interpretation of cultural and natural resources. Venture Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Leed, E. J. (1991). The mind of the traveler: From Gilgamesh to global tourism. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lyell, C. (1830–1833). Principles of geology: Being an attempt to explain the former changes of by the earth’s surface, reference to causes now in operation (3 volumes). John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Mabey, R. (1986). Gilbert White: A biography of the author of the natural history of selbourne. Century Hutchinson. [Google Scholar]

- Mahomed, S. D. (1826). Shampooing; or, benefits resulting from the use of the Indian medicated vapour bath as introducedinto this country by S. D. Mahomed. Creasy & Baker. [Google Scholar]

- Mantell, G. A. (1822). The fossils of the south downs; or illustrations of the geology of Sussex. Lupton Relfe. [Google Scholar]

- Mantell, G. A. (1827). Illustrations of the geology of Sussex containing a general view of the geological relations of the south-eastern part of England: With figures and descriptions of the fossils of Tilgate forest. Lupton Relfe. [Google Scholar]

- Mantell, G. A. (1833). The geology of the south-east of England. Longman, Rees, Orme. [Google Scholar]

- Mantell, G. A. (1844). Medals of creation; or, first lessons in geology, and in the study of organic remains (2 vols.). Henry G. Bohn. [Google Scholar]

- Mantell, G. A. (1846). A day’s ramble in and around the ancient town of Lewes. Henry Bohn. [Google Scholar]

- Mantell, G. A. (1847). Geological excursion round the Isle of Wight and along the adjacent coast of Dorsetshire: Illustrative of the most interesting geological phenomena and organic remains. Henry G. Bohn. [Google Scholar]

- Mantell, G. A. (1854). Geological excursion round the Isle of Wight and along the adjacent coast of Dorsetshire: Illustrative of the most interesting geological phenomena and organic remains (3rd ed.). Henry G. Bohn. [Google Scholar]

- Measom, G. M. (1853). The official illustrated guide to the Brighton and south coast railways and all their branches, including a description of the crystal palace at Sydenham, and a topographical account of the Isle of Wight. H.G. Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Measom, G. M. (1858). The official illustrated guide to the south-eastern railway and its branches, including the north Kent and greenwhich lines. H.G. Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Migon, P. (2016). Rediscovering geoheritage, reinventing geotourism: 200 years of experience from the Sudetes, Central Europe. In T. A. Hose (Ed.), Appreciating physical landscapes: Three hundred years of geotourism—Special publications, 417 (pp. 215–228). The Geological Society of London. [Google Scholar]

- Moir, E. (1964). The discovery of Britain: The English tourists 1540–1840. Routledge & Keagan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Monckton, H. W., & Herries, R. S. (Eds.). (1909). Geology in the field: The jubilee volume of the geologists’ association, 1858–1908. Stanford. [Google Scholar]

- Morley, F. (1983). Literary Britain: A reader’s guide to its writers and its landmarks. Dorset Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, C. (Ed.). (1949). The journeys of Celia Fiennes. Cresset. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, T. D. (1908). British highways and byways from a motor car: Being a record of a five thousand mile tour in Englnad, Wales and Scotland. L.E. Page & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J. (1858). A handbook for travellers in Kent and Sussex. John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, M. W. (1887). A popular guide to the geology of the Isle of Wight, with a note on its relation to that of the Isle of Purbeck. Knight’s Library. [Google Scholar]

- Parris, L., Flemming-Williams, I., & Shields, C. (1976). Constable paintings, watercolours & drawings. The Tate Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, W. (1818). A selection of facts from the best authorities, arranged so as to form an outline of the geology of England and Wales. William Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Pierssene, A. (1999). Explaining our world: An approach to the art of environmental interpretation. Spon. [Google Scholar]

- Reynard, E., Hoblea, F., Cayla, N., & Gauchon, C. (2011). Iconic sites for alpine geology and geomorphology rediscovering heritage? Revue de Ge’o graphie Alpine: New Heritage: Objects, Actors and Controversy Nouveaux Patrimoines, 99(2), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D. K. (1984). The landscape of Thomas Hardy. Webb & Bower. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, R. (1752). A dissertation on the use of sea-water in the diseases of the glands. Particularly the scurvy, jaundice, King’s-evil, leprosy, and the glandular consumption, translated from the Latin of Richard Russel, M.D. by an Eminent Phyfian. W. Owen/R. Goadby. [Google Scholar]

- Sadry, B. N. (2021). The scope and nature of geotourism in the 21st century. In B. N. Sadry (Ed.), The geotourism industry in the 21st century (pp. 3–21). Apple Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sager, F., & Rosser, C. (2015). Historical Methods. In M. Bevir, & R. A. W. Rhodes (Eds.), The routledge handbook of interpretive political science (pp. 199–210). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick. (1822). Article III: On the geology of the Isle of Wight. The Annals of Philosophy, New Series, 3(III), 328–356. [Google Scholar]

- Shanes, E. (1981). Turner’s rivers, harbours and coasts. Chatton & Windus. [Google Scholar]

- Shanes, E. (1990). Turner’s England 1810–1838. Cassell. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, W. C. F. G. (1833). A topographical and historical guide to Isle of Wight. T. Brettell. [Google Scholar]

- Shiflett, O. L. (1984). Clio’s claim: The role of historical research in library and information science. Library Trends, 32(4), 385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Sillitoe, A. (1995). Leading the blind: A century of guidebook travel 1815–1911. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Stainton, L. (1985). British landscape watercolours 1600–1860. British Museum Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Štrba, L., & Palgutová, S. (2024). Geoheritage interpretation panels in UNESCO global geoparks: Recommendations and Assessment. Geoheritage, 16(96), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, R. (2001). Antiquaries and antiquities in eighteenth-century England. Eighteenth-Century Studies, 34(2), 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndyke, A. H. (1920). Literature in a changing age. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Tilden, F. (1977). Interpreting our heritage (3rd ed.). University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turnock, D. (1998). An historical geography of railways in Great Britain and Ireleand. Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2000). UNESCO geoparks programme feasibility study, August 2000. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- van den Ancker, J. A. M. H., & Jungerius, P. D. (2016). Landscape and geotourism on the Dutch coast in the seventeenth century as depicted by landscape artists. In T. A. Hose (Ed.), Appreciating physical landscapes: Three hundred years of geotourism—Special publications, 417 (pp. 71–82). The Geological Society of London. [Google Scholar]

- Vasiljevic, D. A., Markovic, S. B., & Vujicic, M. D. (2016). Appreciating loess landscapes through history: The basis of modern loess geotourism in the Vojvodina region of North Serbia. In T. A. Hose (Ed.), Appreciating physical landscapes: Three hundred years of geotourism—Special publications, 417 (pp. 229–239). The Geological Society of London. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, W. (1999). Arcadia. In W. Vaughan (Ed.), British painting: The golden age (pp. 205–237). Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Veverka, J. A. (1994). Interpretive master planning. Falcon. [Google Scholar]

- Walford, T. (1818). The scientific tourist through England, Wales, & Scotland by which the traveller is directed to the principal objects of antiquity, art, science, and the Picturesque, including the minerals, fossils, rare plants, and other subjects of natural history arranged by counties to which is added an introduction to the study of antiquities, and the elements of statistics, geology, mineralogy, and botany (Vol. 1). J. Booth. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, P. J. (1983). Town, city, and nation: England 1850–1914. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whalley, B. W. (2022). Earth science, art and coastal engineering at the seaside: Envisioning an open exploratorium or geo-promenade at Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, United Kingdom. Geoheritage, 14(113), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, E. P. (1861). A concise exposition of the geology, antiquities, and topography of the Isle of Wight. T. Kentfield. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, H. B. (1907). The history of the geological society of London. The Geological Society of London. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, J. (1995). Wordsworth and the geologists. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Coastal Location(s) + County Excursion Numbers | Totals | Year | Coastal Location(s) + County Excursion Numbers | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | Folkestone + 1 | 2 | 1891 | Isle of Wight +4 | 5 | |

| 1862 | Hastings; Lewes | 2 | 1892 | 2 | 2 | |

| 1863 | Herne Bay & Reculver | 1 | 1893 | Sandgate & Folkestone + 4 | 5 | |

| 1864 | Isle of Wight | 1 | 1894 | Bournemouth & Barton; Herne Bay + 4 | 6 | |

| 1866 | Isle of Wight; Brighton | 2 | 1895 | Isle of Wight + 8 | 9 | |

| 1870 | Herne Bay; Folkestone + 2 | 4 | 1896 | 2 | 2 | |

| 1872 | 4 | 4 | 1897 | Walmer, St. Margarets, Dover, Folkestone & Romney Marsh + 7 | 6 | |

| 1873 | Brighton; Eastbourne & St. Leonards | 2 | 1898 | Sheppey + 5 | 6 | |

| 1874 | 2 | 2 | 1899 | Aldrington, Brighton & Rottingdean + 5 | 6 | |

| 1875 | Isle of Thanet; Sheppey + 1 | 3 | 1900 | Eastbourne & Seaford + 8 | 9 | |

| 1876 | Sandgate & Folkestone + 2 | 3 | 1901 | 7 | 7 | |

| 1877 | 4 | 4 | 1902 | 5 | 5 | |

| 1878 | 2 | 2 | 1903 | 4 | 4 | |

| 1879 | 7 | 7 | 1904 | Hastings; Selsey & Chichester + 2 | 3 | |

| 1880 | Bournemouth; Barton Cliffs; Hampshire coast + 3 | 6 | 1905 | Isle of Thanet; + 3 | 4 | |

| 1881 | Isle of Wight; Sheppey + 1 | 2 | 1906 | Battle & Netherfield; Isle of Wight; Lewes + 3 | 6 | |

| 1882 | Battle & Hastings + 3 | 4 | 1907 | Hastings; Seaford & Newhaven + 8 | 10 | |

| 1883 | 3 | 3 | 1908 | 9 | 9 | |

| 1884 | 3 | 3 | 1909 | Brighton + 8 | 9 | |

| 1885 | Canterbury, Reculver, Pegwell Bay & Richborough + 3 | 4 | 1910 | Sheppey + 6 | 7 | |

| 1886 | Dungness, Rye & Hastings + 2 | 3 | 1911 | 5 | 5 | |

| 1887 | Sheppey; Southampton + 2 | 4 | 1912 | Reculvers + 6 | 7 | |

| 1889 | 3 | 3 | 1913 | Seaford + 6 | 7 | |

| 1890 | Southampton + 5 | 6 | 1914 | 9 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hose, T.A. Travel, Sea Air and (Geo)Tourism in Coastal Southern England. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030155

Hose TA. Travel, Sea Air and (Geo)Tourism in Coastal Southern England. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(3):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030155

Chicago/Turabian StyleHose, Thomas A. 2025. "Travel, Sea Air and (Geo)Tourism in Coastal Southern England" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 3: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030155

APA StyleHose, T. A. (2025). Travel, Sea Air and (Geo)Tourism in Coastal Southern England. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030155