Sustainable Tourism and Regional Development Through Innovation in the Post-COVID-19 Era: The Case of Hersonissos and Chios

Abstract

1. Introduction

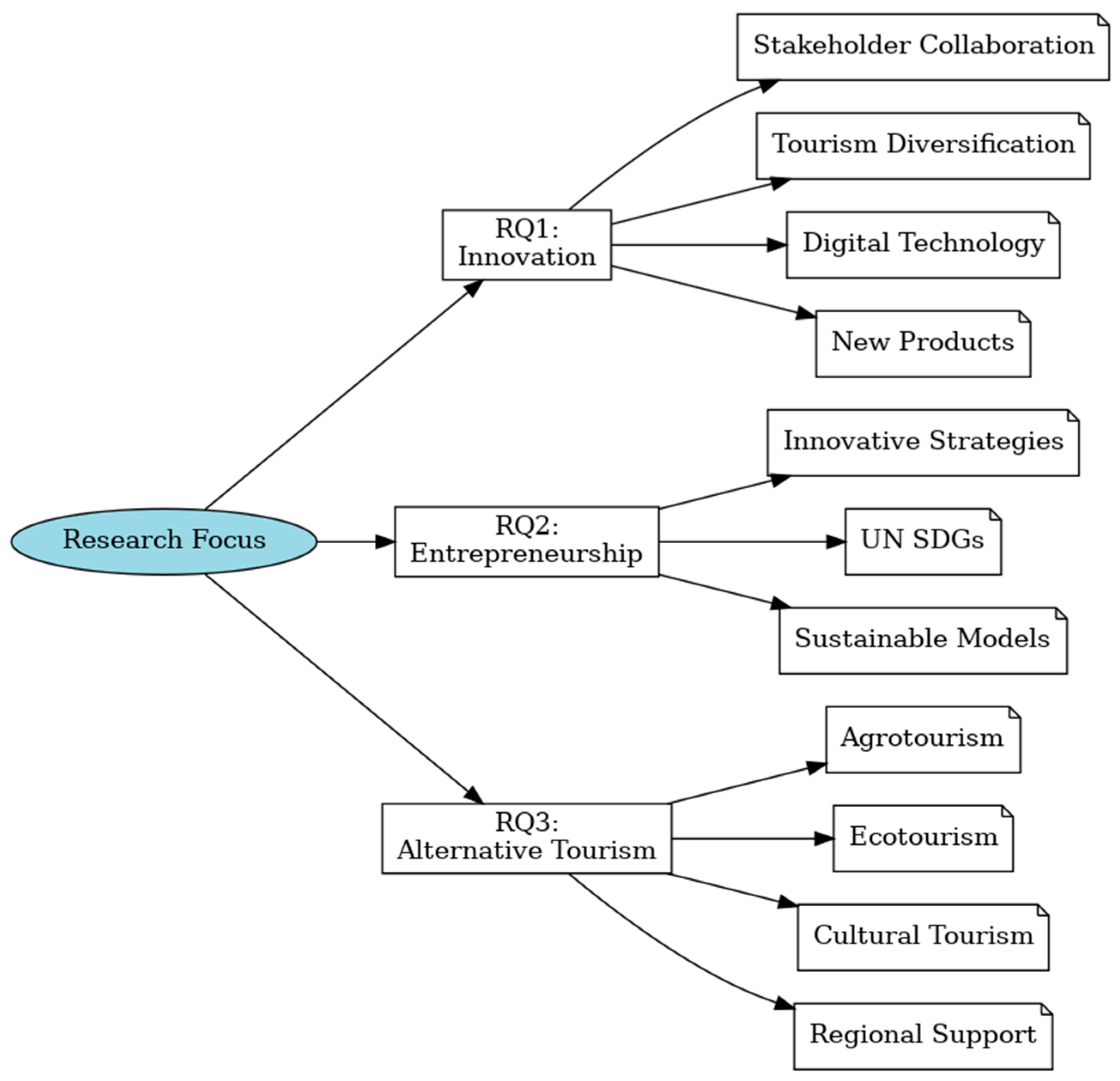

- RQ1: What innovative practices are being implemented in the post-COVID era?

- RQ2: How can tourism entrepreneurship contribute to reducing seasonality?

- RQ3: What are the prospects for developing alternative forms of tourism?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Resilience and Regional Development

2.2. Sustainable Development, Regional Policy, and the Region

2.3. Alternative Tourism and Innovation in Island Destinations

3. EU Policies and Strategies for Regional Development

3.1. Cohesion Policy of the European Union (EU)

3.2. Europe 2020 Strategy and the European Green Deal

3.3. Comparative Overview and Application to the Case Study of Crete and Chios

The Importance of Crisis Management for Sustainable Tourism Development

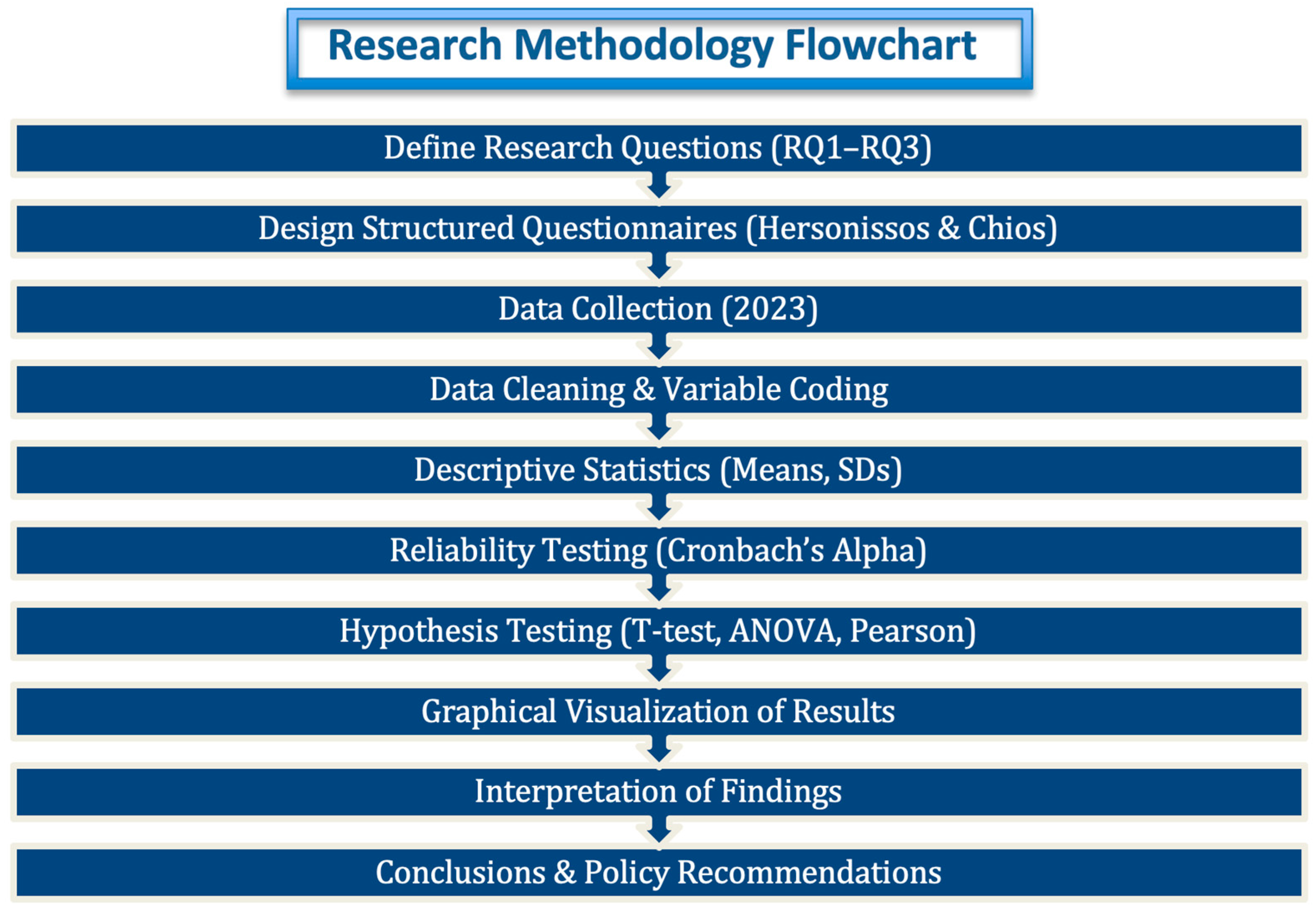

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design

- RQ1—Innovation: What types of innovative practices have been adopted in tourism since the COVID-19 pandemic?

- RQ2—Entrepreneurship and Seasonality: How can tourism entrepreneurship contribute to reducing seasonality and enhancing year-round tourism activity?

- RQ3—Alternative Tourism Forms: What are the local stakeholders’ views regarding the development of alternative and thematic forms of tourism?

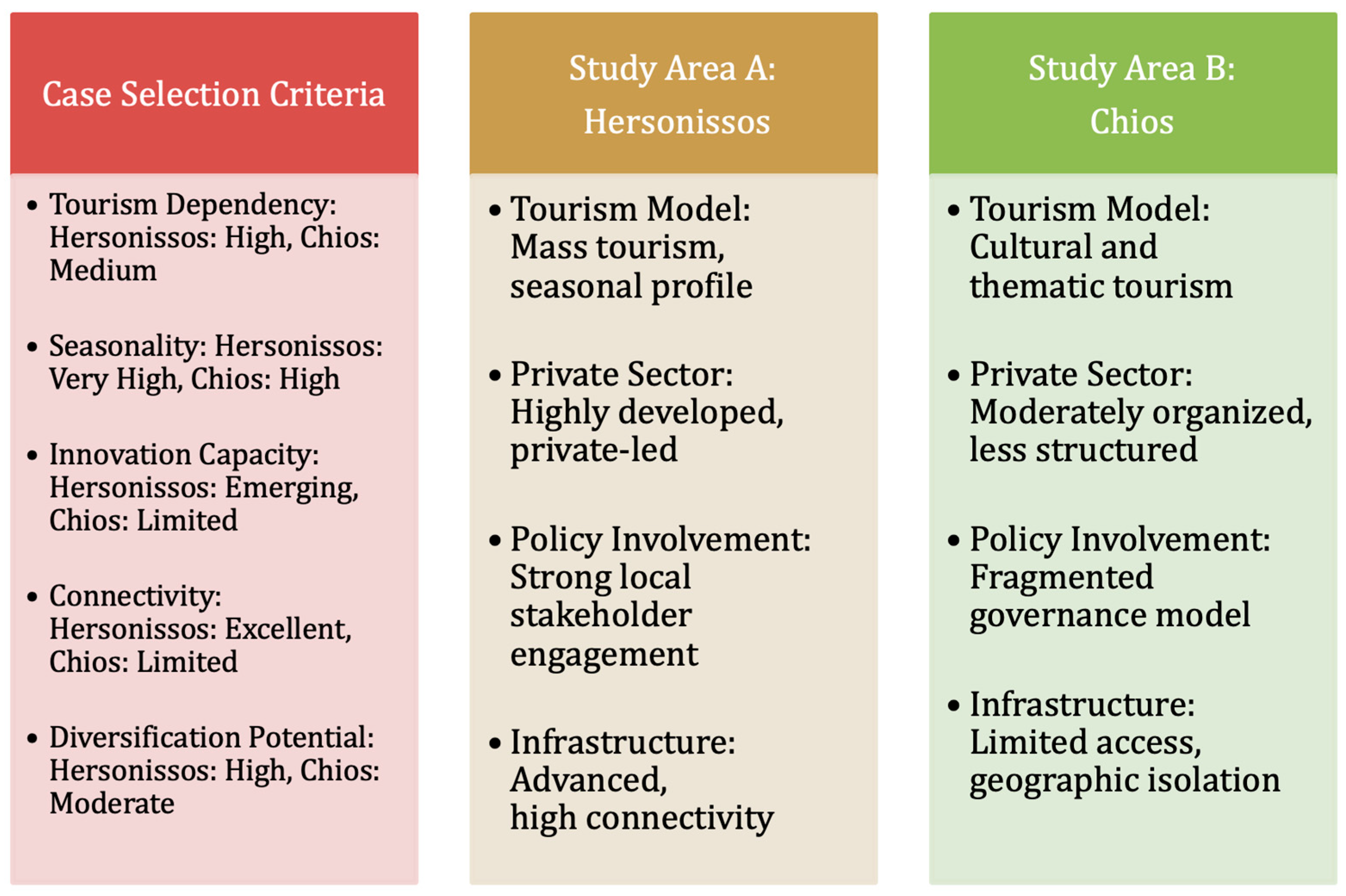

Case Selection

5. Data Collection Procedures

Case Analysis Method

6. Results

6.1. Interpretation of Supportive Questions in the Framework of Regional Development Theory

Findings and Interpretation

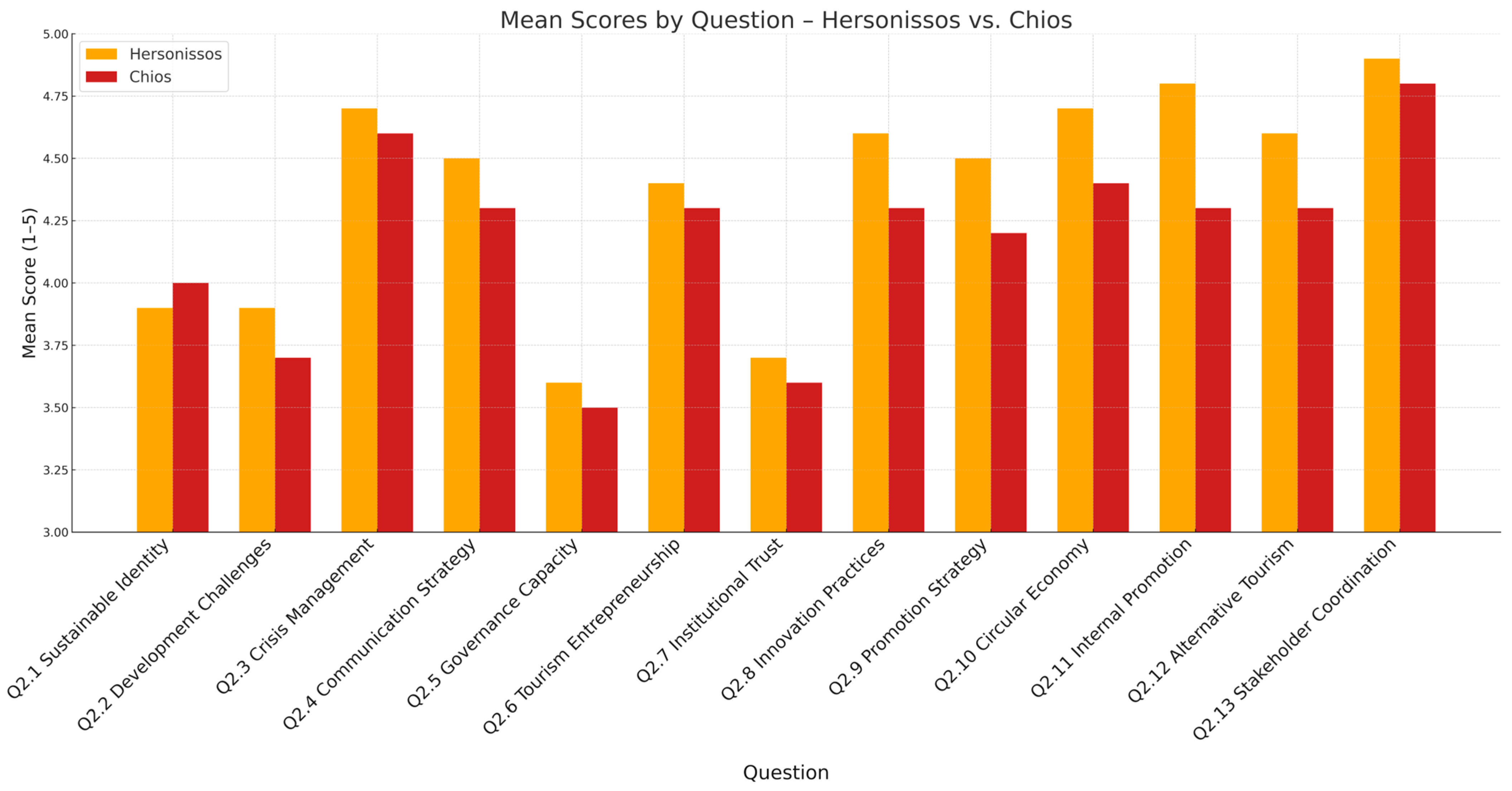

6.2. Visual Summary of Findings

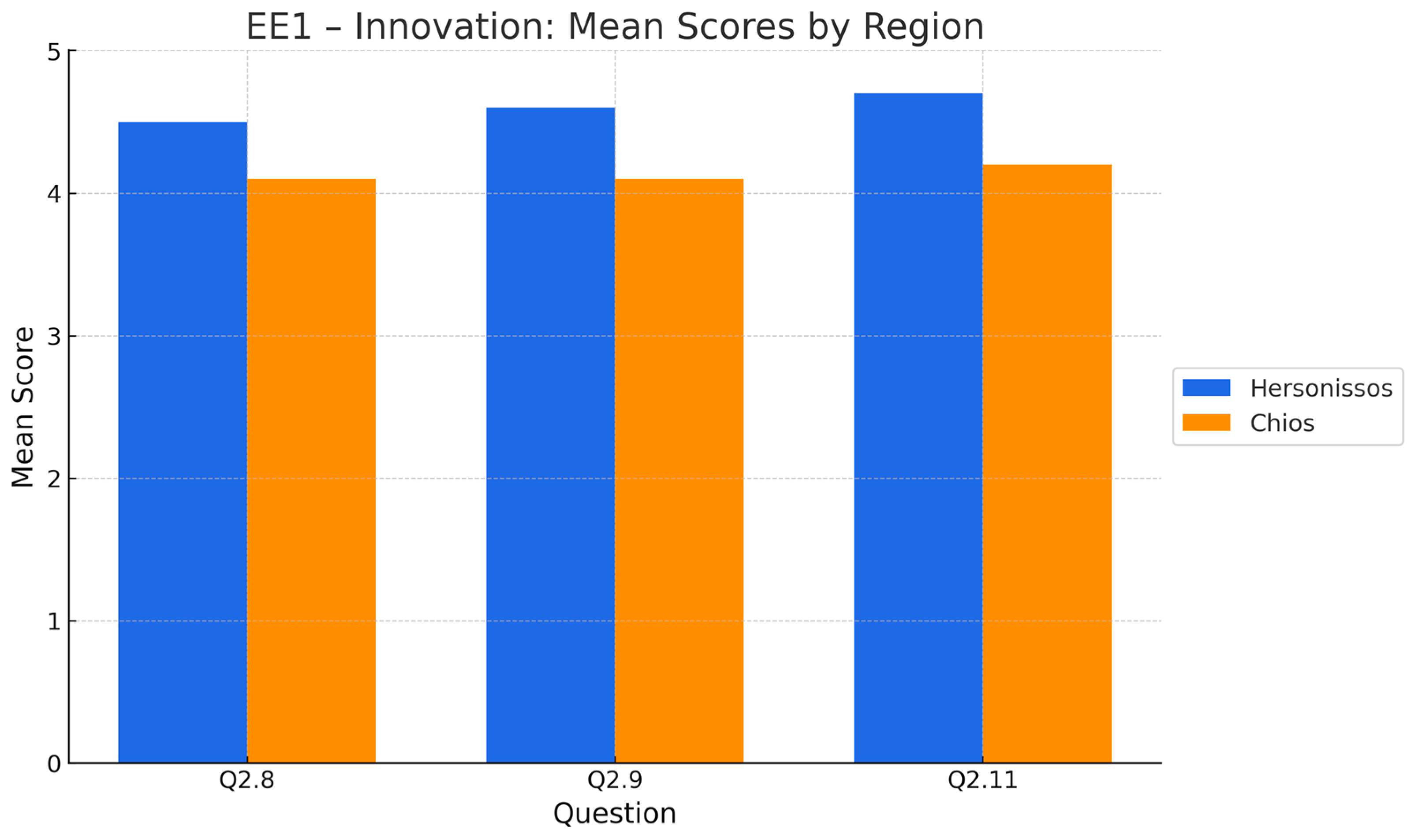

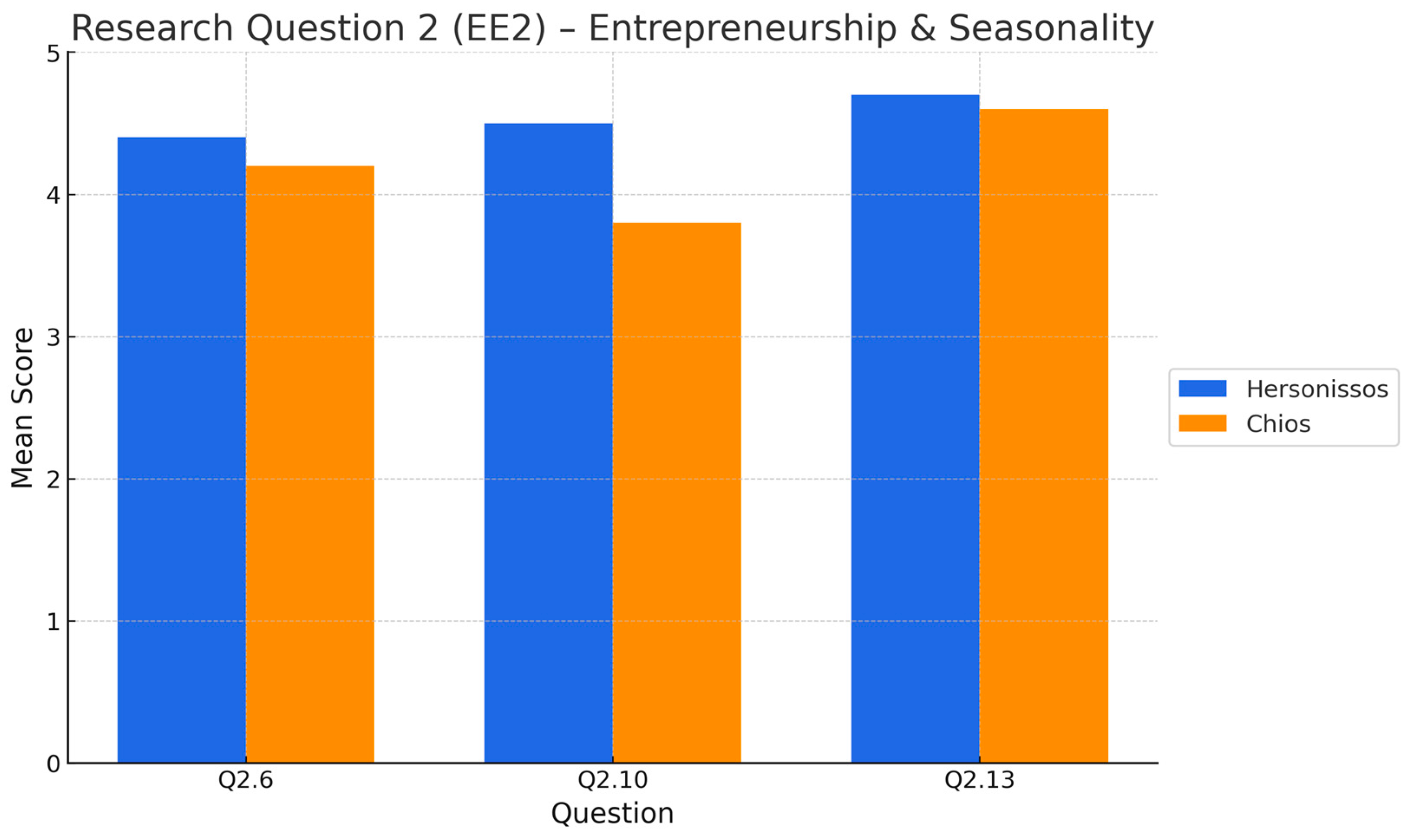

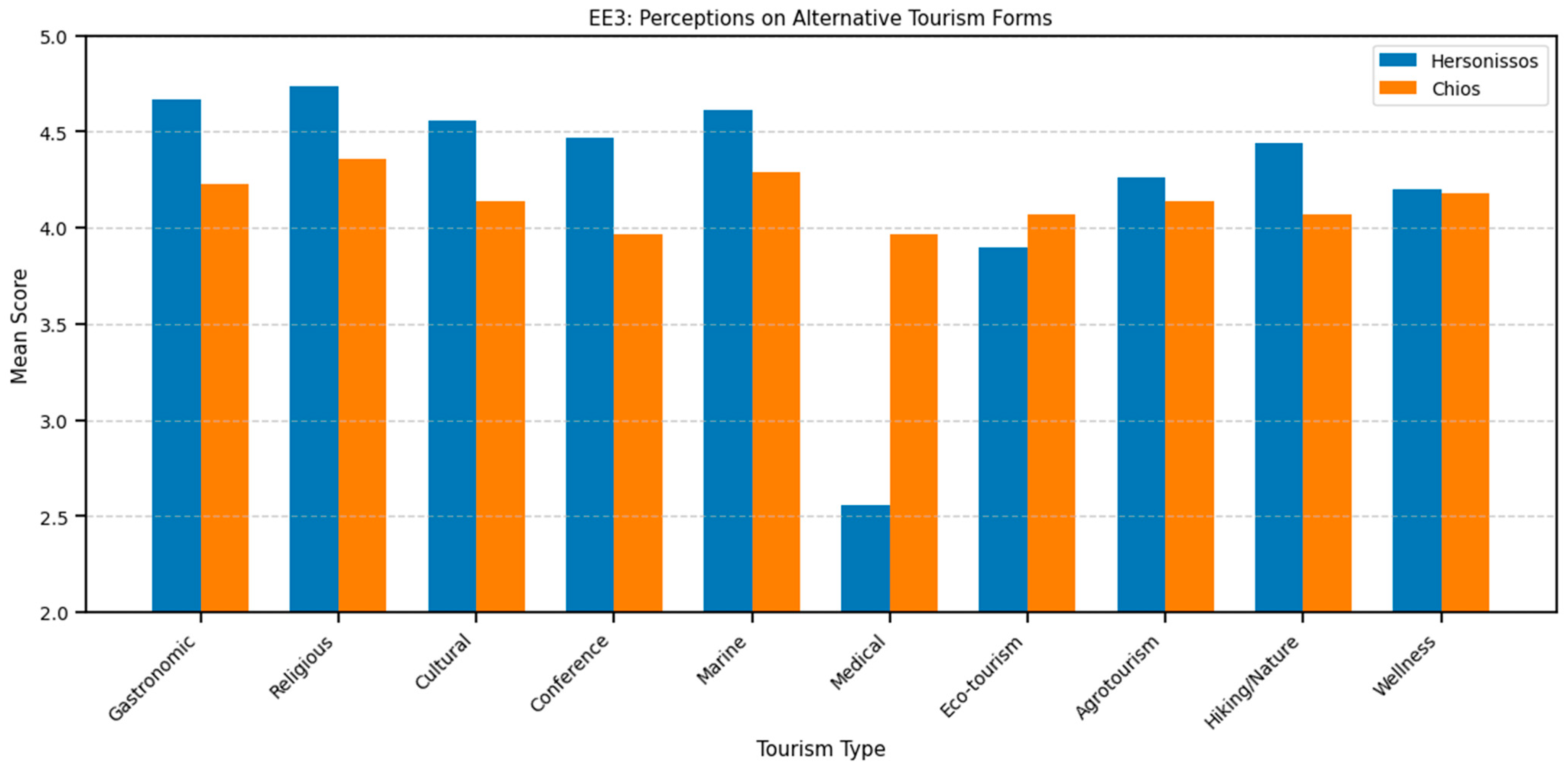

Innovation-Related Items (EE1)—Entrepreneurship and Circular Economy (EE2)—Alternative Tourism Preferences (EE3)

6.3. Policy Challenges and Strategic Tools

6.3.1. Key Challenges Identified

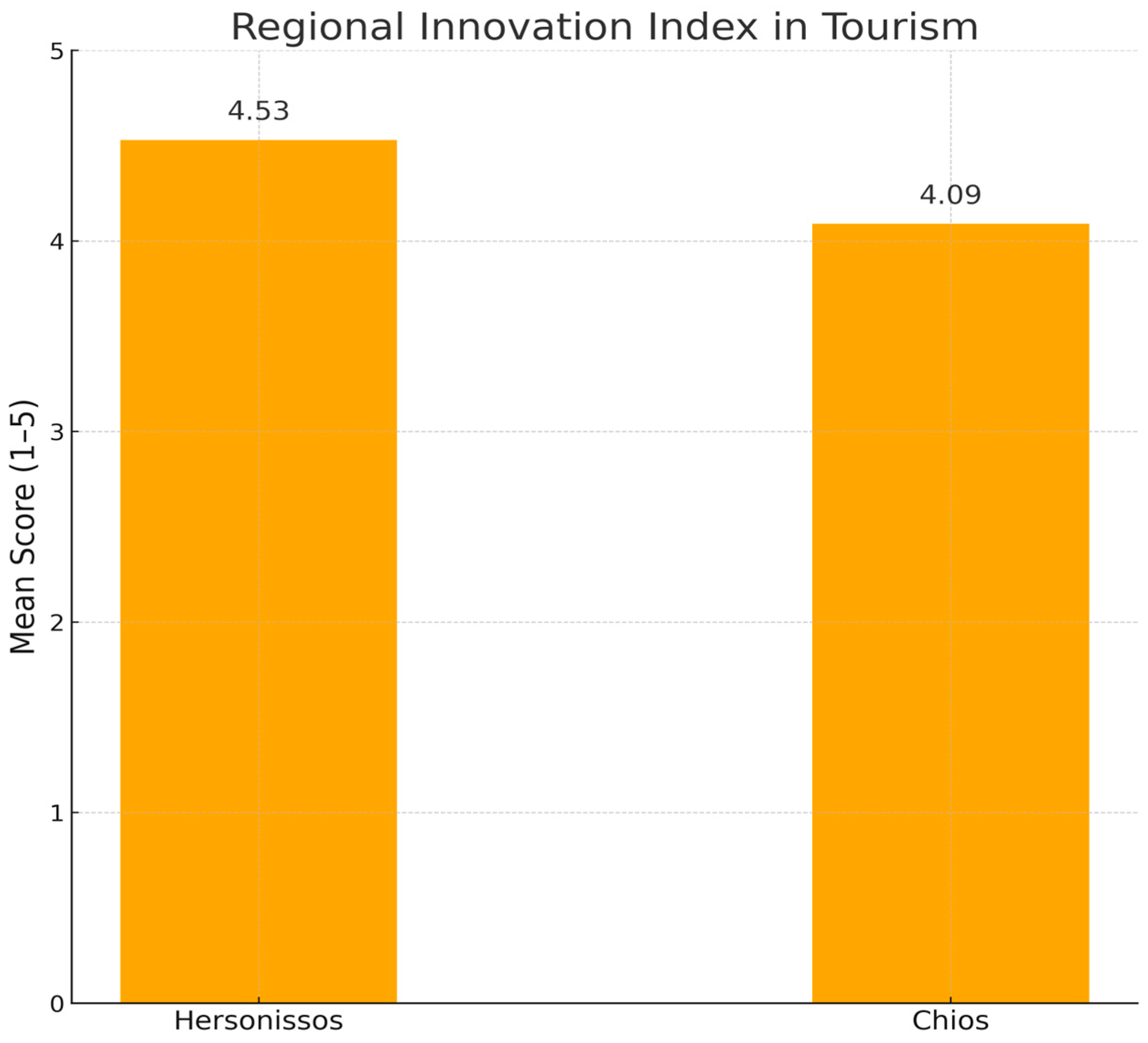

6.3.2. Policy Proposal: Regional Innovation Index for Sustainable Tourism

7. Discussion and Implications

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

8.1. Overall Conclusions

8.2. Policy Recommendations

8.3. Limitations and Future Research

8.4. Final Reflection

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, P., & Parashar, A. (2024). Island and beach-based model: A nature-based health tourism practice at tourism destinations. International Journal of Health Management and Tourism, 9(2), 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniello, G., Többen, J., & Kuckshinrichs, W. (2019). The transition to renewable energy technologies—Impact on economic performance of north Rhine-Westphalia. Applied Sciences, 9(18), 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachtler, J., & Begg, I. (2017). Cohesion policy after Brexit: The economic, social and institutional challenges. Journal of Social Policy, 46(4), 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D., Pitelis, C., & Tomlinson, P. R. (2023). Resilience, sustainability and regional development in Europe: The role of the green economy. Regional Studies, 57(1), 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, M., & Martinez, P. (2019). Sensitivity of agricultural development to water-related drivers: The case of Andalusia (Spain). Water, 11(9), 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, K., Doucet, P., Komornicki, T., Zaucha, J., & Świątek, D. (2011). How to strengthen the territorial dimension of ‘Europe 2020’ and EU cohesion policy. Ministry of Regional Development. [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2011). Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. W. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution. The Canadian Geographer, 24(1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R., & Capello, R. (2010). Macroeconomic and territorial policies for regional competitiveness: An EU perspective. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 2(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R., & Capello, R. (2012a). Regional competitiveness and territorial capital: A conceptual approach and empirical evidence from the European Union. Regional Studies, 47(9), 1383–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R., & Capello, R. (2012b, August 21–25). Regional innovation patterns and the EU regional policy reform: Towards smart innovation policies. 52nd Congress of the European Regional Science Association, Bratislava, Slovakia. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/120488 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Capello, R. (2007). Regional economics. Routledge. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27223043 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Davoudi, S., Brooks, E., & Mehmood, A. (2013). Evolutionary resilience and strategies for climate adaptation. Planning Practice and Research, 28(3), 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2006). Strategy for sustainable development. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=legissum:l28117 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- European Commission. (2010). Europe 2020: A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Available online: https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/news/european-commission-launches-europe-2020-strategy-smart-sustainable-and-inclusive-growth_en (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- European Commission. (2019). Climate action and the Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/climate-action-and-green-deal_en (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- European Commission. (2020). Stepping up Europe’s 2030 climate ambition. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020SC0176 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- European Commission. (2023a). Cohesion policy 2021–2027: Strengthening European regions. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/2021-2027_en (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- European Commission. (2023b). Cohesion policy. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/information-sources/publications/reports/2023/report-on-the-outcome-of-2021-2027-cohesion-policy-programming_en (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- European Commission. (2024). The European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- European Committee of the Regions. (2024). Regions and cities shaping the European Green Deal 2.0. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/64f17ca7-1d63-11ef-a251-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Faludi, A. (2013). Territorial cohesion and subsidiarity under the European Union treaties. Regional Studies, 47(9), 1594–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferry, M., & McMaster, I. (2013). Cohesion policy and the evolution of regional policy in central and eastern Europe. Europe-Asia Studies, 65(8), 1502–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(5), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.-M. (2010). A review of innovation research in tourism. Tourism Management, 31(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSETE. (2021). Greek tourism statistics for 2020. Available online: https://insete.gr/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Executive-Summary_2030.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Jin, Z., & Gao, M. (2025). Global trends in research related to ecotourism: A bibliometric analysis from 2012 to 2022. SAGE Open, 15(1), 21582440251316718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JRC. (2024). Cohesion policy benefits EU’s economy and regions. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/jrc-news-and-updates/cohesion-policy-benefits-eus-economy-and-regions-2024-04-11_en (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Kavaratzis, M. (2004). From city marketing to city branding: Towards a theoretical framework for developing city brands. Place Branding, 1(1), 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2015). On the notion of regional economic resilience: Conceptualization and explanation. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(1), 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marukhlenko, O., & Kuzmenko, D. (2024). Cohesion policy in the EU: Experience for Ukraine in the conditions of post-war reconstruction. Global Scientific Trends: Economics and Public Administration, 3, 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Municipality of Chios. (2025). Meetings with professional bodies for tourism development. Available online: https://www.chios.gov.gr (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Municipality of Hersonissos. (2024). Alternative tourism in the municipality of Hersonissos. Available online: https://www.hersonisos.gr/hersonisos/alternative-tourism (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- North Aegean Region. (2024). Summary of the approved Chios regional operational plan. Available online: https://www.pepba.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Περίληψη_εγκεκρ_ΣΒΑΑ_Χίου.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Pike, S. (2008). Destination marketing: An integrated marketing communication approach (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B., & Peters, M. (2005). Towards the measurement of innovation. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 6(3), 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Region of Crete. (2024). Actions of the tourism directorate of the region of Crete. Available online: https://www.crete.gov.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/απ-1120-28-δράσεις-Δνσης-Τουρισμού-ΠΚ.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Ketterer, T. (2020). Institutional change and the development of lagging regions in Europe. Regional Studies, 54(7), 974–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R., & Telfer, D. J. (2015). Tourism and development in the developing world. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Similä, J., Soininen, N., & Paukku, E. (2021). Towards sustainable blue energy production. Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 40(1), 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmie, J., & Martin, R. (2010). The economic resilience of regions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

| Bibliographic Source | Research Question Framework | Mind Map Focus | Relation to Questionnaire |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hjalager (2010) | RQ1 | Innovation, technology | 2.8, 2.9, and 2.11 |

| Sigala (2020) | RQ1 | Recovery, digital innovation | 2.4, 2.8, and 2.11 |

| Pikkemaat and Peters (2005) | RQ1 | New products | 2.8, 2.11 |

| Butler (1980) | RQ2 | Seasonality | 2.6, 2.9, and 2.10 |

| Gössling et al. (2020) | RQ1 and RQ2 | Post-COVID sustainability | 2.6, 2.10, and 2.13 |

| Bramwell and Lane (2011) | RQ1 and RQ2 | Governance/stakeholder engagement | 2.5, 2.10, and 2.13 |

| Capello (2007) | RQ2 | Regional economy | 2.6, 2.9, 2.10, and 2.13 |

| Sharpley and Telfer (2015) | RQ2 and RQ3 | Development in the south/alternative tourism | 2.6, 2.10, and 2.12 |

| Region | Thematic Area | Questionnaires | Desk Research | Field Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hersonissos | Innovation and entrepreneurship | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hersonissos | Seasonality and strategy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hersonissos | Alternative tourism | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Chios | Innovation and entrepreneurship | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Chios | Seasonality and strategy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Chios | Alternative tourism | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Question | Key Finding | Theoretical Framework | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q2.1 | Strong support for rebranding and sustainable identity | Endogenous Development | Indicates readiness for local transformation and cultural anchoring |

| Q2.2 | Awareness of difficulties in achieving sustainability | Political Economy | Points to structural barriers that may limit transition |

| Q2.3 | High awareness of crisis phases and response | Regional Resilience | Suggests strategic preparedness and learning from shocks |

| Q2.4 | Strong value placed on communication | Spatial Economics & Innovation | Supports role of storytelling and branding in policy |

| Q2.5 | Moderate confidence in governance structures | Multilevel Governance | Highlights administrative gaps and decentralization needs |

| Q2.7 | Medium trust in institutions | Social Capital Theory | Emphasizes importance of participatory approaches |

| Q2.13 | Very high support for inter-agency collaboration | Institutional Resilience | Opportunity for strategic synergy and cross-sector action |

| Research Question | Region | Mean (Approx.) | Notable Differences | Gender Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE1—Innovation | Hersonissos | 4.5–4.8 | Higher emphasis on strategic innovation | Women rated innovation higher |

| Chios | 4.0–4.3 | Slightly more conservative views | No significant gender differences | |

| EE2—Entrepreneurship | Hersonissos | 4.5–4.7 | Stronger alignment with resilience strategy | Minor gender tendency in favor of women |

| Chios | 4.2–4.4 | High agreement across items | Similar trend | |

| EE3—Alternative Tourism | Hersonissos | 4.5–4.8 | Preference for themed & gastronomy | Women preferred eco-tourism |

| Chios | 4.1–4.4 | Focus on medical, eco, agro models | No major gender differences |

| Descriptive Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | N | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| Hersonissos | 35 | 4.53 | 0.43 |

| Chios | 35 | 4.09 | 0.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kritikos, A.; Magoutas, A.; Poulaki, P. Sustainable Tourism and Regional Development Through Innovation in the Post-COVID-19 Era: The Case of Hersonissos and Chios. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030134

Kritikos A, Magoutas A, Poulaki P. Sustainable Tourism and Regional Development Through Innovation in the Post-COVID-19 Era: The Case of Hersonissos and Chios. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(3):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030134

Chicago/Turabian StyleKritikos, Antonis, Anastasios Magoutas, and Panoraia Poulaki. 2025. "Sustainable Tourism and Regional Development Through Innovation in the Post-COVID-19 Era: The Case of Hersonissos and Chios" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 3: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030134

APA StyleKritikos, A., Magoutas, A., & Poulaki, P. (2025). Sustainable Tourism and Regional Development Through Innovation in the Post-COVID-19 Era: The Case of Hersonissos and Chios. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030134