The Profile of Wine Tourists and the Factors Affecting Their Wine-Related Attitudes: The Case of Türkiye

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Demographic characteristics (age, sex, marital status, education, income, etc.);

- (2)

- Psychographic features (lifestyles and motivations).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Demographic Characteristics of Wine Tourists

2.2. Psychographic Characteristics of Wine Tourists

2.3. Lifestyle Typologies of Wine Tourists

3. Materials and Methods

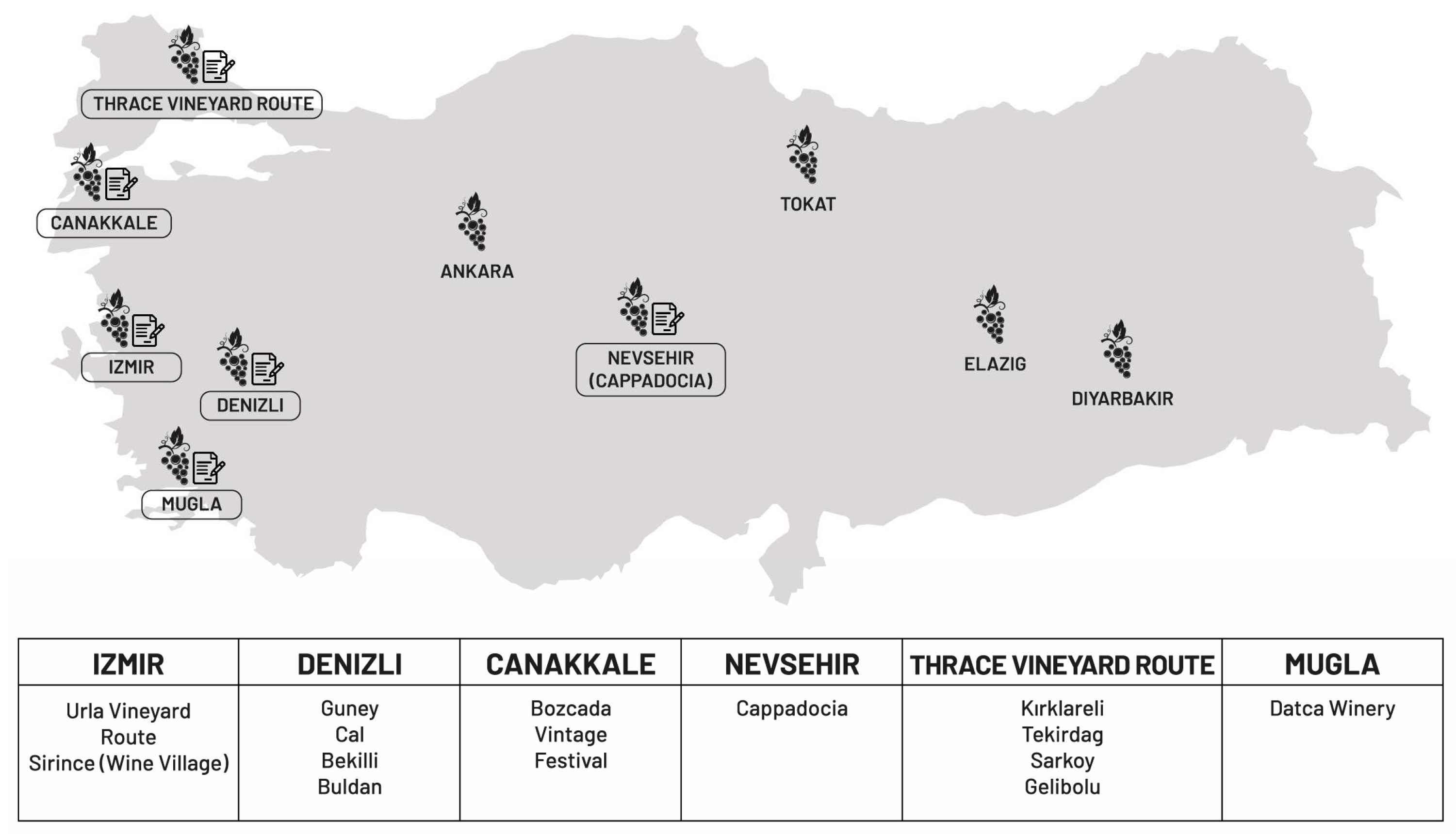

3.1. Study Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Results on the Demographic Profile of Wine Tourists

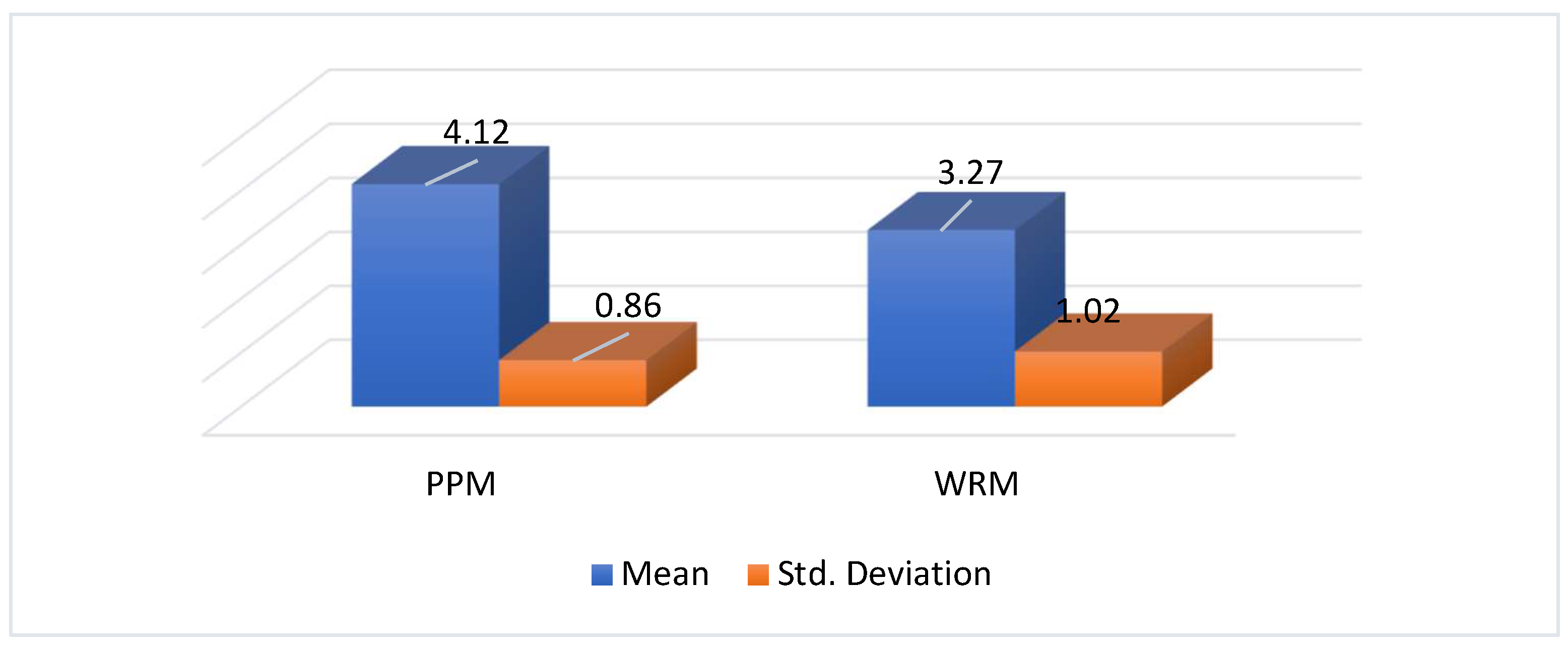

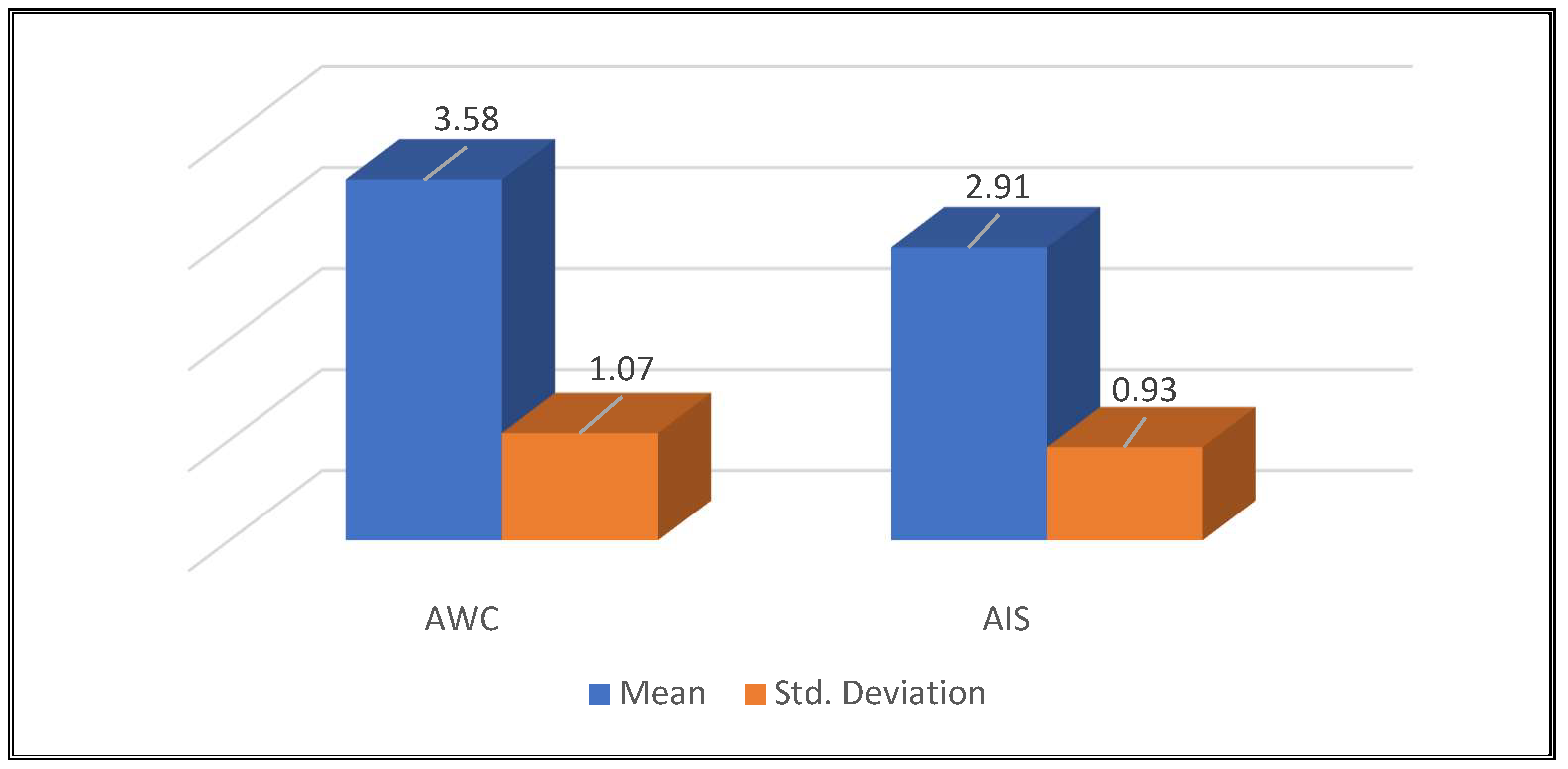

4.2. Results on the Psychographic Profile of Wine Tourists

4.3. Results on Relationship Between Demographics and Psychographics and Attitudes Towards Wine Tourism

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Limitations and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The original survey was removed from the Internet as Strategic Business Insights ceased its operations in 2024. |

References

- Adnan, A., Uddin, S. F., & Mehdi, M. (2022). Developing a new lifestyle instrument: An analytic hierarchy process-based approach. International Journal of Business Innovation and Research, 27(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadimanesh, M., & Helaliyan, M. H. (2022). Hypermarket segmentation based on lifestyle criteria of VALS, to identify the customers’ requirements using Kano model and prioritize their motivational needs using DANP (DEMATEL and ANP) case study: Daily chain hypermarket. Journal of Systems Thinking in Practice, 1(2), 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Alebaki, M., & Iakovidou, O. (2004, November 2–4). Wine tourism and the characteristics of winery visitors: The case of wine roads of Northern Greece. 9th Pan-Hellenic Congress of Greek Association of Agricultural Economists, Athens, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Alebaki, M., & Iakovidou, O. (2011). Market segmentation in wine tourism: A comparison of approaches. Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism, 6(1), 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beames, G. (2003). The rock, the reef and the grape: The challenges of developing wine tourism in regional Australia. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 9(3), 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekar, A., & Şahin, S. K. (2017). Attempts of reviving the 4000 years of history of winemaking in the ancient city of cnidus and bringing it into gastronomy tourism. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 5(3), 236–253. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, E. J. (1983). Ads enlist ambiguity to target varied lifestyles, values. Ad Forum, 4, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bharwani, S., & Jauhari, V. (2013). An exploratory study of competencies required to co-create memorable customer experiences in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(6), 823–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, R. D., Miniard, P. W., & Engel, J. F. (2001). Consumer behavior (9th ed.). Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer, J. (2003). South African wine routes: Some perspectives on the wine tourism industry’s structural dimensions and wine tourism product. Tourism Management, 24(4), 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J., & Alant, K. (2009). The hedonic nature of wine tourism consumption: An experiential view. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 21(3), 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J., Li, E., & Reid, M. (2002). Segmentation of the australian wine market using a wine-related lifestyle approach. Journal of Wine Research, 13(3), 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitello, R., Sidali, K. L., & Schamel, G. (2021). Wine terroir commitment in the development of a wine destination. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62(3), 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, B. (2005). Understanding the wine tourism experience for winery visitors in the Niagara Region, Ontario, Canada. Tourism Geographies, 7(2), 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S., McCleary, K. W., & Uysal, M. (1995). Travel motivations of Japanese overseas travelers: A factorcluster segmentation approach. Journal of Travel Research, 34(1), 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S., & Ali-Knight, J. (2002). Who is the wine tourist? Tourism Management, 23, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S., & Carlsen, J. (2006). Conclusion: The future of wine tourism research, management and marketing. In J. Carlsen, & S. Charters (Eds.), Global wine tourism: Research management and marketing (pp. 263–275). CABI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, G. M. (1977). Anomie, ego-enhancement and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 4(4), 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, T. (1995). Opportunities and pitfalls of tourism in a developing wine industry. International Journal of Wine Marketing, 7(1), 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. (2021). Statistical yearbook: World food and agriculture. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/522c9fe3-0fe2-47ea-8aac-f85bb6507776/content (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucile Franceschini, C., Giampietri, E., & Pomarici, E. (2025). What defines the perfect wine tourism experience? Evidence from a best–worst approach. Agriculture, 15(8), 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, G., Mitchell, R., Getz, D., Crouch, G., & Ong, B. (2008). Sensation seeking and the prediction of attitudes and behaviours of wine tourists. Tourism Management, 29(5), 950–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. (2000). Explore wine tourism: Management, development and destinations. Cognizant Communication Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Carmona, D., Paramio, A., Cruces-Montes, S., Marín-Dueñas, P. P., Montero, A. A., & Romero-Moreno, A. (2023). The effect of the wine tourism experience. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 29, 100793. [Google Scholar]

- Güzel, Ö., Ehtiyar, R., & Ryan, C. (2021). The Success Factors of wine tourism entrepreneurship for rural area: A thematic biographical narrative analysis in Turkey. Journal of Rural Studies, 84, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equations modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C. M. (1996). Wine tourism in New Zealand. In J. Higham (Ed.), Proceedings of tourism down under II: A tourism research conference. University of Otago. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C. M., & Macionis, N. (1998). Wine tourism in Australia & New Zealand. In R. W. Butler, C. M. Hall, & J. Jenkins (Eds.), Tourism & recreation in rural areas (pp. 267–298). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A New criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatov, E., & Smith, S. (2006). Segmenting canadian culinary tourists. Current Issues in Tourism, 9(3), 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G. (1998). Wine tourism in New Zealand—A national survey of wineries [Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Otago]. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanović, R., Almeida-García, F., Cortés-Macías, R., & Parzych, K. (2025). Assessment of wine tourism potential in the countries of the former Yugoslavia. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 49, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Colloboration, 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksal, H., & Seyedimany, A. (2023). Wine consumer typologies based on level of involvement: A case of Turkey. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 35(4), 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Guzmán, T., Millán Vázquez, G., & Caridad y Ocerín, J. M. (2008). Análisis econométrico del enoturismo en España. Un estudio de caso. Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo, 17(1), 98–118. [Google Scholar]

- Macionis, N. (1997). Wine tourism in Australia: Emergence, development and critical issues [Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Canberra]. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe, B., & Bauman, M. J. (2019). Terroir tourism: Experiences in organic vineyards. Beverages, 5(2), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlowe, B., & Lee, S. (2018). Conceptualizing terroir wine tourism. Tourism Review International, 22(2), 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K., Hattenberger, G., Pechlaner, H., & Abfalter, D. (2005). Lifestyle segmentation, vacation types and guest satisfaction: The case of Alpine skiing tourism. In C. Cooper, C. Arcodia, & D. W. M. Solnet (Eds.), CAUTHE 2004: Creating tourism knowledge. A selection of papers from Cauthe 2004–2005 (pp. 127–137). CAUTHE. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R., & Hall, C. M. (2006). Wine tourism research: The state of play. Tourism Review International, 9, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R., Hall, C. M., & McIntosh, A. (2000). Wine tourism and consumer behavior. In C. M. Hall, E. Sharples, B. Cambourne, & N. Macionis (Eds.), Wine tourism around the world: Development, management and markets (pp. 115–135). Butterworth-Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, M., & Palmer, A. (2004). Wine production and tourism: Adding service to a perfect partnership. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 45(3), 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S., & Getz, D. (1997). The business of rural tourism: International perspectives. International Thomson Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peršurić, A. S. I., Damijanić, A. T., & Šergo, Z. (2019). The wine tourism terroir: Experiences from Istria. Tourism in Southern and Eastern Europe, 5, 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, M. (2014, June 28–30). Four wine tourist profiles. Academy of Wine Business Research, 8th International Conference, Geisenheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice, R. C., Witt, S. F., & Hamer, C. (1998). Tourism as experience: The case of heritage parks. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenscroft, N., & van Westering, J. (2001). Wine tourism, culture and the everyday: A theoretical note. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3(2), 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, I. E. A., Cajilema, C. H. A., Aguinaga, A. G. A., & Andino, G. F. T. (2022). Influence of needs and lifestyles on the bop consumer: A perspective in Ecuador. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, L., Bednall, D., Cowley, E., O’cass, A., Watson, J., & Kanuk, L. (2001). Consumer behavior (2nd ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, D. (1986). VALS as a tool of tourism market research: The Pennsylvania experience. Journal of Travel Research, 24(4), 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M., & Prideaux, B. (2009). Developing a food and wine segmentation and classifying destinations on the basis of their food and wine sectors. Advances in Hospitality and Leisure, 5, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treloar, P., Hall, C. M., & Mitchell, R. (2004, February 10–13). Wine tourism and generation Y market: Any possibilities? CAUTHE Conference 2004: Creating Tourism Knowledge, Brisbane, OLD, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Wedel, M., & Kamakura, W. (2000). Market segmentation: Conceptual and methodological foundations (2nd ed.). Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, H. M., Sünnetçioğlu, A., & Atay, L. (2018). Yaşam tarzının yeşil otel tercihinde rolü. Anemon Muş Alparslan Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 6, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, S., & Güner, D. (2021). “Şarap Turizmi”. In E. Çilesiz, & O. S. Doğancılı (Eds.), Alternatif turizm kapsaminda güncel konular ve araştirmalar (pp. 63–81). Çizgi Kitabevi. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Destination | Demographics of Wine Tourists |

|---|---|---|

| Dodd (1995) | Texas, USA | High education and income |

| Treloar et al. (2004) | New Zealand | Mostly female, 30–50 years old, well-educated, professional, high-income, mostly domestic tourists |

| O’Neill and Palmer (2004) | Australia | Female, young, in a managerial or professional occupation, well-educated, and domestic tourists |

| Ignatov and Smith (2006) | Canada | Equal numbers of male and female tourists, average age, average education level, and high income |

| Lopez-Guzmán et al. (2008) | South of Spain | Aged 50–59, middle or high income, often visiting with family |

| Bekar and Şahin (2017) | Datca, Türkiye | Aged 50 and over, middle- and upper-income level, high education level |

| Item Code | Factor Load | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WRM | 0.871 | 0.903 | 0609 | ||

| My motivation for this travel is to visit wineries. | WRM1 | 0.841 | |||

| …is to meet the winemaker. | WRM2 | 0.796 | |||

| …is to learn winemaking. | WRM3 | 0.795 | |||

| …is to buy wine. | WRM4 | 0.802 | |||

| …is to taste wine. | WRM5 | 0.780 | |||

| …is to attend the vintage. | WRM6 | 0.653 | |||

| PPM | 0.770 | 0.894 | 0.809 | ||

| …is to taste local food and drinks. | PPM3 | 0.934 | |||

| …is the cultural attractions in the region. | PPM5 | 0.863 | |||

| AWC | 0.892 | 0.920 | 0.699 | ||

| I like to taste types of wine. | AWC1 | 0.888 | |||

| I like to drink wine. | AWC2 | 0.872 | |||

| Drinking wine is good for the health as long as it is not in excess. | AWC3 | 0.793 | |||

| I buy wine from wineries. | AWC4 | 0.836 | |||

| I visit wineries. | AWC5 | 0.787 | |||

| AIS | 0.838 | 0.884 | 0.605 | ||

| I read magazines about wine. | AIS1 | 0.775 | |||

| I follow TV programs about wine. | AIS2 | 0.764 | |||

| I meet many people through wine. | AIS3 | 0.789 | |||

| I know most types of wine. | AIS4 | 0.797 | |||

| I attend wine or vintage festivals. | AIS5 | 0.764 | |||

| Believers | 0.790 | 0.855 | 0.544 | ||

| Religion is the most important way to know what’s morally correct. | VALS27 | 0.830 | |||

| The government should encourage prayers in public schools. | VALS13 | 0.806 | |||

| No matter how much evil I see in the world, my faith in God is strong. | VALS29 | 0.705 | |||

| Just as the (Holy Book) says, the world literally was created in six days. | VALS6 | 0.675 | |||

| There is too much sex on television today. | VALS20 | 0.655 | |||

| Strivers | 0.811 | 0.860 | 0.674 | ||

| I like to dress in the latest fashions. | VALS19 | 0.727 | |||

| I follow the latest trends and fashions. | VALS5 | 0.781 | |||

| I dress more fashionably than most people. | VALS12 | 0.940 | |||

| Experiencers | 0.696 | 0.814 | 0.525 | ||

| I like trying new things. | VALS17 | 0.811 | |||

| I would like to understand more about how the universe works. | VALS34 | 0.654 | |||

| I like doing things that are new and different. | VALS32 | 0.779 | |||

| I like to learn about art, culture, and history. | VALS8 | 0.638 | |||

| Innovators | 0.854 | 0.901 | 0.753 | ||

| A good negotiator doesn’t just get the food in the bowl, but the bowl itself. | VALS31 | 0.957 | |||

| I like a lot of excitement in my life. | VALS23 | 0.823 | |||

| I often crave excitement. | VALS9 | 0.815 | |||

| Makers | 0.623 | 0.764 | 0.529 | ||

| I like making things of wood, metal, or other such material. | VALS25 | 0.914 | |||

| I love to make things I can use every day. | VALS4 | 0.642 | |||

| I like to make things with my hands. | VALS30 | 0.582 | |||

| Achievers | 0.621 | 0.762 | 0.522 | ||

| I like to lead others. | VALS21 | 0.783 | |||

| I like being in charge of a group. | VALS7 | 0.554 | |||

| I like the challenge of doing something I have never done before. | VALS28 | 0.804 |

| AIS | AWC | A | B | E | I | M | PPM | S | WRM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIS | 0.778 * | |||||||||

| AWC | 0.663 | 0.836 * | ||||||||

| Achievers (A) | 0.103 | 0.177 | 0.723 * | |||||||

| Believers (B) | −0.273 | −0.489 | 0.057 | 0.738 * | ||||||

| Experiencers (E) | −0.065 | 0.117 | 0.315 | 0.028 | 0.725 * | |||||

| Innovators (I) | 0.070 | 0.091 | 0.365 | 0.139 | 0.332 | 0.867 * | ||||

| Makers (M) | 0.066 | 0.047 | 0.191 | 0.123 | 0.281 | 0.193 | 0.727 * | |||

| PPM | 0.114 | 0.128 | 0.164 | 0.080 | 0.285 | 0.154 | 0.098 | 0.899 * | ||

| Strivers (S) | 0.134 | 0.072 | 0.204 | 0.152 | 0.209 | 0.198 | 0.072 | 0.069 | 0.821 * | |

| WRM | 0.603 | 0.692 | 0.184 | −0.285 | 0.082 | 0.179 | 0.080 | 0.196 | 0.077 | 0.780 * |

| AIS | AWC | A | B | E | I | M | PPM | S | WRM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIS | ||||||||||

| AWC | 0.759 | |||||||||

| Achievers (A) | 0.116 | 0.186 | ||||||||

| Believers (B) | 0.320 | 0.568 | 0.150 | |||||||

| Experiencers (E) | 0.103 | 0.145 | 0.497 | 0.125 | ||||||

| Innovators (I) | 0.104 | 0.085 | 0.523 | 0.199 | 0.430 | |||||

| Makers (M) | 0.097 | 0.078 | 0.404 | 0.210 | 0.477 | 0.277 | ||||

| PPM | 0.136 | 0.148 | 0.215 | 0.123 | 0.389 | 0.175 | 0.122 | |||

| Strivers (S) | 0.121 | 0.067 | 0.290 | 0.221 | 0.286 | 0.303 | 0.206 | 0.096 | ||

| WRM | 0.698 | 0.766 | 0.213 | 0.315 | 0.124 | 0.190 | 0.127 | 0.232 | 0.089 |

| Sex | Percentage | Marital Status | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 52.7 | Married | 33.4 |

| Male | 47.3 | Single | 66.6 |

| Age (years) | Monthly average income (per person) * | ||

| 18–24 | 32.4 | EUR 435 or below | 29.0 |

| 25–34 | 33.2 | EUR 436–740 | 18.9 |

| 35–44 | 17.8 | EUR 741–1050 | 18.5 |

| 45–54 | 7.1 | EUR 1051–1355 | 11.0 |

| 55 and older | 9.5 | EUR 1356 or above | 22.6 |

| Education level | Having children | ||

| Primary and/or secondary education | 11.4 | Yes | 24.7 |

| Associate/bachelor’s degree | 66.2 | No | 75.3 |

| Postgraduate degree | 22.4 | ||

| Place of Residence | Occupation | ||

| Türkiye | 91.3 | Student | 31.5 |

| USA | 2.5 | Private Sector Employee | 28.6 |

| Spain | 1.7 | Public Sector Employee | 15.8 |

| France | 1.5 | Self-employed | 9.1 |

| Germany | 1.5 | Retired | 7.5 |

| Japan | 1.4 | Unemployed | 7.5 |

| Travel companion | |||

| Alone | 12.7 | ||

| With friends | 47.5 | ||

| With partner | 23.6 | ||

| With family (partner and children) | 9.1 | ||

| With parents | 7.1 |

| Demographics | Dimensions of AWT | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWC | AIS | |||||||||

| n | ± SD | t | F | p | n | ± SD | t | F | p | |

| Female | 273 | 3.53 ± 1.10 | −1.144 | - | 0.253 | 273 | 2.85 ± 0.95 | −1.503 | - | 0.134 |

| Male | 245 | 3.64 ± 1.03 | 245 | 2.97 ± 0.91 | ||||||

| Married | 173 | 3.57 ± 1.10 | −0.266 | - | 0.790 | 173 | 2.89 ± 1.00 | −0.295 | - | 0.776 |

| Single | 345 | 3.59 ± 1.05 | 345 | 2.92 ± 0.09 | ||||||

| 18–24 | 168 | 3.35 ± 1.11 | - | 3.349 | 0.010 * | 168 | 2.74 ± 0.91 | - | 2.018 | 0.091 |

| 25–34 | 172 | 3.75 ± 1.10 | 172 | 3.01 ± 0.86 | ||||||

| 35–44 | 92 | 3.61 ± 1.16 | 92 | 2.93 ± 1.06 | ||||||

| 45–54 | 37 | 3.67 ± 0.09 | 37 | 3.02 ± 0.96 | ||||||

| 55 and above | 49 | 3.71 ± 0.95 | 49 | 2.98 ± 0.92 | ||||||

| Primary and/or secondary education | 59 | 2.55 ± 1.34 | - | 35.212 | 0.000 * | 59 | 2.24 ± 1.06 | - | 18.545 | 0.000 * |

| Associate/bachelor’s degree | 343 | 3.71 ± 0.91 | 343 | 2.97 ± 0.84 | ||||||

| Postgraduate degree | 116 | 3.73 ± 1.07 | 116 | 3.07 ± 1.00 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 39 | 2.98 ± 1.19 | - | 5.941 | 0.000 * | 39 | 2.35 ± 0.81 | - | 4.700 | 0.000 * |

| Private sector employee | 148 | 3.80 ± 0.95 | 148 | 3.05 ± 0.93 | ||||||

| Public sector employee | 82 | 3.69 ± 1.01 | 82 | 2.93 ± 0.91 | ||||||

| Retired | 39 | 3.66 ± 1.00 | 39 | 2.97 ± 0.94 | ||||||

| Self-employed | 47 | 3.88 ± 0.93 | 47 | 3.16 ± 0.96 | ||||||

| Student | 163 | 3.38 ± 1.13 | 163 | 2.81 ± 0.92 | ||||||

| EUR 435 and below | 150 | 3.07 ± 1.20 | - | 13.717 | 0.000 * | 150 | 2.53 ± 0.89 | - | 9.000 | 0.000 * |

| EUR 436–740 | 98 | 3.73 ± 0.99 | 98 | 3.09 ± 0.95 | ||||||

| EUR 741–1050 | 96 | 3.73 ± 1.00 | 96 | 3.05 ± 0.95 | ||||||

| EUR 1051–1355 | 57 | 3.82 ± 0.94 | 57 | 3.03 ± 0.83 | ||||||

| EUR 1356 and above | 117 | 3.89 ± 0.83 | 117 | 3.06 ± 0.88 | ||||||

| Hypothesis | Sub-Hypothesis | Paths | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | H1a AWT—Sex | AWC—Sex | unsupported |

| AIS—Sex | unsupported | ||

| H1b AWT—Marital status | AWC—Marital status | unsupported | |

| AIS—Marital status | unsupported | ||

| H1c AWT—Age | AWC—Age | supported | |

| AIS—Age | unsupported | ||

| H1d AWT—Education | AWC—Education | supported | |

| AIS—Education | supported | ||

| H1e AWT—Occupation | AWC—Occupation | supported | |

| AIS—Occupation | supported | ||

| H1f AWT—Income | AWC—Income | supported | |

| AIS—Income | supported |

| Paths | R2 | Q2 | VIF | f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WRM → AWC PPM → AWC Believer → AWC Striver → AWC Experiencer → AWC Innovator → AWC Maker → AWC Achiever → AWC | 0.585 | 0.399 | 1.235 1.150 1.204 1.108 1.343 1.295 1.126 1.259 | 0.641 0.001 0.231 0.008 0.003 0.001 0.001 0.008 |

| WRM → AIS PPM → AIS Believer → AIS Striver → AIS Experiencer → AIS Innovator → AIS Maker → AIS Achiever → AIS | 0.410 | 0.240 | 1.235 1.150 1.204 1.108 1.343 1.295 1.126 1.259 | 0.409 0.003 0.030 0.030 0.038 0.000 0.008 0.000 |

| Paths | Beta Co. | SD | t | p | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | H2a | WRM → AWC | 0573 | 0.032 | 18.118 | 0.000 ** | Supported |

| H2b | WRM → AIS | 0.546 | 0.039 | 13.871 | 0.000 ** | Supported | |

| H2c | PPM → AWC | 0.017 | 0.033 | 0.511 | 0.609 | Unsupported | |

| H2d | PPM → AIS | 0.048 | 0.038 | 1.260 | 0.208 | Unsupported | |

| H3 | H3a | Believer → AWC | −0.340 | 0.032 | 10.774 | 0.000 ** | Supported |

| H3b | Striver → AWC | 0.059 | 0.038 | 1.569 | 0.117 | Unsupported | |

| H3c | Experience → AWC | 0.043 | 0.041 | 1.050 | 0.294 | Unsupported | |

| H3d | Innovators → AWC | −0.020 | 0.035 | 0.580 | 0.562 | Unsupported | |

| H3e | Makers → AWC | 0.016 | 0.036 | 0.458 | 0.647 | Unsupported | |

| H3f | Achievers → AWC | 0.066 | 0.035 | 1.895 | 0.058 | Unsupported | |

| H3a | Believer → AIS | −0.146 | 0.040 | 3.667 | 0.000 ** | Supported | |

| H3b | Striver → AIS | 0.139 | 0.052 | 2.693 | 0.007 ** | Supported | |

| H3c | Experiencer → AIS | −0.174 | 0.055 | 3.144 | 0.002 ** | Supported | |

| H3d | Innovators → AIS | −0.009 | 0.045 | 0.192 | 0.848 | Unsupported | |

| H3e | Makers → AIS | 0.072 | 0.060 | 1.198 | 0.231 | Unsupported | |

| H3f | Achievers → AIS | 0.017 | 0.038 | 0.434 | 0.664 | Unsupported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bekar, A.; Benzergil, N. The Profile of Wine Tourists and the Factors Affecting Their Wine-Related Attitudes: The Case of Türkiye. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030132

Bekar A, Benzergil N. The Profile of Wine Tourists and the Factors Affecting Their Wine-Related Attitudes: The Case of Türkiye. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(3):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030132

Chicago/Turabian StyleBekar, Aydan, and Nisan Benzergil. 2025. "The Profile of Wine Tourists and the Factors Affecting Their Wine-Related Attitudes: The Case of Türkiye" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 3: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030132

APA StyleBekar, A., & Benzergil, N. (2025). The Profile of Wine Tourists and the Factors Affecting Their Wine-Related Attitudes: The Case of Türkiye. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030132