Abstract

This study develops and tests an integrated structural equation model (SEM) linking Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC), residents’ quality of life (QoL), and community participation in sustainable tourism governance (STG) across three emerging island destinations in Aceh, Indonesia. Drawing on survey data from 1266 residents, we employ confirmatory factor analysis and covariance-based SEM to (1) assess the direct effects of TALC-derived dimensions on residents’ QoL; (2) examine the influence of residents’ QoL on governance participation; and (3) evaluate both direct and indirect pathways linking TALC to STG. Rather than distinct life cycle stages, we conceptualize and measure residents’ perceptions of destination maturity based on key TALC dimensions, such as infrastructure development, tourism intensity, and institutional coordination. Results indicate that higher perceived destination maturity is positively associated with residents’ QoL (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), and that residents’ QoL strongly predicts governance participation (β = 0.31, p < 0.001). TALC dimensions also directly affect STG (β = 0.23, p < 0.001), with residents’ QoL partially mediating this relationship and accounting for 22.4% of the total effect. Multigroup SEM reveals consistent effect patterns across Weh, Pulo Aceh, and Simeulue. These findings illustrate how TALC-informed perceptions of destination maturity relate to residents’ quality of life and governance participation, suggesting that perceived well-being may play an important role in shaping community engagement in small-island tourism contexts.

1. Introduction

Tourism has evolved from a discretionary pastime into a recognized contributor to human well-being and social inclusion. Access to leisure and travel is increasingly recognized as a critical quality of life (QoL) component, with demonstrated benefits to physical, emotional, and relational well-being (Bagheri et al., 2024; Konstantopoulou et al., 2024). Early work focused on tourists’ QoL—showing how holidays enhance happiness and life satisfaction—but scholars now emphasize that sustainable tourism must also uplift host communities’ QoL (Uysal et al., 2016).

Island tourism is pivotal in regional economies, offering livelihoods through hospitality services, heritage preservation, and small-scale entrepreneurship. Yet its sustainable success hinges on visitor flows and meaningful stakeholder involvement, particularly residents’ collaboration, commitment, and positive engagement in tourism planning and management (Javdan et al., 2024). Around the globe, island destinations experience opportunities and challenges from tourism. On the upside, tourism contributes significantly to the GDP, stimulates entrepreneurship, and finances infrastructure upgrades (Baloch et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2022). It also underwrites cultural heritage preservation as residents respond to the demand for authentic experiences (Gössling et al., 2021; Nguyen Thi et al., 2024). However, unchecked growth often leads to overcrowding, environmental degradation, rising living costs, and cultural commodification, eroding social cohesion and diminishing QoL (Hall, 2024; Yanes et al., 2019). Balancing these good and bad features is critical for long-term destination sustainability.

These dynamics are acutely felt in Aceh’s islands (Indonesia), such as Pulo Aceh, Simeulue, and Weh. Following the 2004 tsunami and the end of the conflict, tourism was championed for reconstruction and economic revitalization (Daly et al., 2012; Jayasuriya & McCawley, 2010). This focus led to tangible improvements in accessibility and spurred development centered on marine tourism potential (Daly et al., 2012). However, the rapid prioritization of tourism within a complex post-disaster and post-conflict setting, combined with inherent island’s vulnerabilities, presents significant challenges. These include persistent infrastructure gaps hindering development, environmental pressures threatening the natural assets underpinning marine tourism, socio-cultural tensions arising from balancing tourism growth with local norms (including Sharia law), concerns over equitable distribution of tourism benefits, difficulties in fostering effective community participation in governance, and the imperative to manage visitor impacts to protect ecosystems and resident well-being.

Bridging the tourist experience and resident well-being is a central challenge in destination development. To understand and potentially manage these complex dynamics over time, Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) offers a valuable lens: as destinations transition from exploration through consolidation to decline (Butler, 1980, 2009), visitor amenities and access improve; however, residents may face rising costs and environmental pressures. However, while useful, TALC has been critiqued for its singular focus on visitor numbers and infrastructure. It often neglects the deeper social, cultural, and environmental dynamics and implications experienced by residents (Ramón-Cardona & Sánchez-Fernández, 2024). Moreover, sustainable tourism scholars have called for community-centric models that integrate life cycle theory with social outcomes (e.g., Rasoolimanesh et al., 2020; Spadaro et al., 2023), but empirical investigations linking TALC stages to residents’ QoL and governance behaviors remain scarce.

Addressing these gaps, the present study develops and tests an integrated structural equation modeling (SEM) framework that (1) quantifies the direct effect of TALC dimensions on residents’ QoL (e.g., safety, healthcare, cultural integrity); (2) assesses the direct effect of residents’ QoL on Sustainable Tourism Governance (STG); (3) examines the direct effect of TALC on STG, independent of QoL; and (4) evaluates the mediating role of residents’ QoL in the relationship between TALC dimensions and STG, specifically testing for partial mediation.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Tourism Area Life Cycle

Butler’s (1980, 2009) Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) remains a cornerstone for analyzing destination evolution, positing that destinations progress through stages—exploration, involvement, development, consolidation, stagnation, and decline—based on visitor numbers and infrastructure growth. While TALC’s utility in forecasting tourism trajectories is well-documented (Butler, 2009; Weaver, 2012), recent critiques caution against reducing it to a deterministic S-curve that overlooks the complex socio-environmental dynamics shaping destination development.

Gore et al. (2024) map tourism strategy patterns onto the TALC framework, revealing a cycle-recycle development process rather than a simple S-curve. They find that central and state governments and private entrepreneurs independently and often collaboratively deploy stage-specific strategies, alternating between piecemeal tactical shifts and comprehensive, global changes to stimulate or sustain development at different TALC stages. Some scholars also argue that TALC’s focus on quantitative metrics (e.g., tourist arrivals, hotel capacity) neglects qualitative shifts in resident well-being and ecological resilience (e.g., Diedrich & García-Buades, 2009; Garay & Cànoves, 2011).

These limitations are especially pronounced in island destinations, where geographic isolation, ecological fragility, and climate vulnerability heighten the stakes of tourism development (Gössling et al., 2021). Residents are more acutely aware of tourism’s trade-offs in such settings, particularly when infrastructure growth outpaces environmental safeguards or equitable service delivery. Ramón-Cardona and Sánchez-Fernández (2024) demonstrate this, noting that Ibiza’s transition to consolidation exacerbated resident anxieties over cultural commodification and ecological strain, underscoring the need to integrate socio-cultural indicators into TALC frameworks. Likewise, Kedang and Soesilo (2021) revealed that Bintan’s TALC-driven expansion prioritized tourist convenience over equitable community benefits, exacerbating socio-economic disparities. These studies collectively advocate reimagining TALC as a social-ecological model, sensitive to how tourism progression reshapes power, resource access, and cultural legitimacy.

In this study, we adopt a dimensional and perceptual operationalization of TALC. Rather than assigning destinations to discrete stages, we measure residents’ perceptions of destination maturity based on multiple TALC-informed dimensions, including infrastructure adequacy, tourism intensity, promotional reach, and stakeholder coordination. This approach reflects Butler’s (1980) own caution that the model is not universally prescriptive and should be adapted to local contexts. It also aligns with more recent calls to apply TALC as a flexible, evolutionary framework rather than a fixed sequence of stages (Agarwal, 2002; Ma & Hassink, 2013). Empirical studies have shown that local communities interpret tourism development through subjective experiences tied to infrastructure, service access, and institutional responsiveness (Baum, 1998; Volgger & Pechlaner, 2014). By conceptualizing TALC as a continuum of perceived maturity, we extend its applicability to structural equation modeling and facilitate its integration with constructs such as quality of life and sustainable tourism governance.

2.2. Residents’ Quality of Life

Recent scholarship positions resident quality of life (QoL) not merely as an outcome of tourism but as the central mechanism linking broader structural factors to community support for sustainable practices. Ramkissoon (2023) develops a conceptual model in which the perceived social impacts of tourism, such as enhanced community pride and increased social interaction, foster interpersonal trust and place attachment, which drive pro-social and pro-environmental behaviors in support of tourism development. Building on this conceptual foundation, Javdan et al. (2024) provide village-level evidence that when residents perceive tangible benefits, such as improved public services, economic opportunities, and cultural exchange, their overall QoL ratings increase markedly, leading to a greater willingness to endorse tourism initiatives.

Complementing these findings, Yayla et al. (2023) employ SEM on survey data from 468 Turkish residents to demonstrate that the perceived economic, social, and environmental impacts of tourism significantly enhance resident quality of life (QoL), which in turn mediates their support for further tourism development. However, Peypoch et al. (2024) find a mixed relationship in 40 Chinese cities: while tourism efficiency delivers economic gains, it does not directly translate into QoL improvements unless accompanied by robust social services and environmental safeguards.

Together, these studies underscore the importance of modeling QoL as a mediator. Nonetheless, a critical gap remains: no empirical research has yet examined QoL’s mediating role in linking Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) maturity to sustained community participation in governance. Our study addresses this by integrating TALC dimensions, QoL indicators, and governance engagement within a unified SEM framework. Having established QoL as the key mechanism through which tourism impacts translate into community support, we next turn to the governance frameworks that empower or hinder residents’ ability to shape sustainable tourism outcomes.

2.3. Sustainable Tourism Governance

While quality of life (QoL) mediates tourism impacts and community support, sustainable tourism governance (STG) determines whether QoL gains are institutionalized and equitably distributed. Drawing on Buhalis’ tourism sustainability paradigm (Mihalic, 2022), effective STG integrates layers of (1) strategic leadership (vision/commitment), (2) governance mechanisms (collaborative structures/policy formulation), and (3) implementation/execution (concrete actions). This framework conceptualizes STG through policy co-creation (core mechanism) and environmental stewardship (fundamental implementation action), balancing trade-offs and reinforcing socio-cultural outcomes for resident support.

STG manifests through policies across levels, directly impacting Aceh’s island communities. At the macro level (national/provincial), policies include post-tsunami revitalization strategies (Daly et al., 2012; Jayasuriya & McCawley, 2010), marine protected areas (MPAs), and infrastructure funding to enable accessibility. These often degrade resident QoL through insufficient local infrastructure, top-down planning prioritizing visitors, and inconsistent environmental regulation enforcement. At the micro-level (local/community), initiatives like community-based tourism bylaws and village regulations foster economic benefits but face persistent challenges: ineffective stakeholder participation failing to translate into meaningful influence (Hampton & Jeyacheya, 2015; Liu-Lastres et al., 2020), tensions between Sharia law implementation and tourism development (Rindrasih, 2019), and limited authority/resources hindering implementation.

This multilevel interplay underscores governance’s centrality—and its critical gap. Despite governance being vital for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Rasoolimanesh et al. (2020) find it remains the most neglected dimension in sustainability indicators, with scant attention to mechanisms like co-creation or implementation like stewardship in the Global South. While empirical models like 4P partnerships (Spadaro et al., 2023) and community ecotourism (Chan et al., 2021) demonstrate how collaborative mechanisms enable stewardship and legitimacy, most governance structures are static. Crucially, they fail to adapt across perceived destination maturity—our core premise. The question of how governance mechanisms and implementation actions evolve (or fail to evolve) as destinations mature drives our integration of these concepts within a unified framework.

These governance shortcomings are particularly consequential in island contexts, where structural limitations, such as ecological fragility, geographic remoteness, and narrow economic bases, constrain resilience and magnify the consequences of poor institutional design (Dodds & Graci, 2012; Fischer & Encontre, 1998). Sustainable tourism in small islands requires environmental sensitivity and flexible, inclusive governance systems that adapt to shifting visitor pressures and climate-related risks (Tompkins & Adger, 2004). Yet, as Scheyvens and Momsen (2008) argue, many island tourism models continue to marginalize resident agency and prioritize short-term growth over long-term sustainability. The UNWTO (2017) likewise stresses that inclusive governance is essential to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially for Small Island Developing States (SIDS). In this context, understanding how perceived destination maturity, well-being, and governance participation interact becomes a theoretical concern and a practical necessity for managing tourism in fragile island systems.

2.4. Research Hypotheses

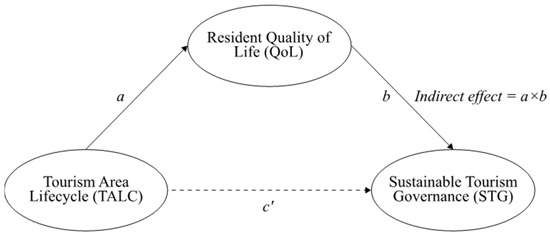

Building on the gaps identified in Section 2.1, Section 2.2 and Section 2.3, we propose a three-layer SEM framework, as shown in Figure 1. The framework integrates structural driver (i.e., key dimensions of TALC, such as infrastructure growth, stakeholder involvement, and promotional intensity), the mediating mechanism (i.e., residents’ QoL, such as safety, healthcare access, and cultural integrity), and governance outcome (i.e., community participation in sustainable tourism governance, such as public monitoring, policy co-creation, and environmental stewardship).

Figure 1.

Conceptual SEM framework.

Furthermore, from the framework, we derive the following four testable hypotheses:

H1.

TALC dimensions have a positive effect on residents’ QoL.

H2.

Residents’ QoL has a positive effect on STG.

H3.

TALC dimensions have a direct positive effect on STG, independent of QoL.

H4.

Residents’ QoL partially mediates the relationship between TALC dimensions and STG.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Technique

To ensure adequate statistical power for our framework, we conducted an a priori power analysis based on Cohen (1988) and Westland (2010) guidelines. Assuming a small-to-medium effect size (f2 = 0.10), desired statistical power 1 − β of 0.80, and α of 0.05, with three latent constructs and 28 observed indicators, the calculated minimum required sample size is 1258 respondents (Faul et al., 2009).

Accordingly, we drew a stratified random sample of 1400 residents to account for nonresponse across three island destinations in Aceh: Weh, Pulo Aceh, and Simeulue. Stratification was based on age, gender, and island, ensuring that each destination’s unique tourism profile and community context were proportionally represented and on resident tenure (newcomers, established, and long-term) to capture variation in local engagement, i.e., direct tourism exposure, such as (1) employment in tourism-adjacent sectors (e.g., hospitality, fisheries supplying resorts); (2) residence distance of 5 km or less from tourist zones; or (3) participation in community tourism forums. It ensured lived experience with governance impacts. These stratification variables were later modeled as covariates in the structural equation framework to control for confounding effects on residents’ QoL and governance outcomes (Kline, 2023; Little, 2013).

3.2. Measurement and Research Instrument

We developed a questionnaire comprising three constructs of tourism area life cycle (TALC) dimensions, resident quality of life (QoL), and sustainable tourism governance (STG), totaling 28 items. Appendix A.1 presents the full questionnaire, showing all 28 items and source attributions, for replication and transparency, and Appendix A.2 shows descriptive statistics.

The TALC dimensions construct includes fourteen indicators adapted from Butler (1980), Kedang and Soesilo (2021), and Gore et al. (2024). Items probe respondents’ views on the destination life cycle, such as whether tourist arrivals have steadily increased over recent years, whether accommodation and transport infrastructure meet evolving visitor needs, and whether promotional activities and stakeholder involvement (public and private) have intensified. Additional items assess the destination’s cultural and environmental management, e.g., whether heritage sites are maintained to high standards and capacity-monitoring practices are in place. Each indicator is rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree), capturing the degree to which each TALC dimension is perceived to be active.

The residents’ QoL construct, drawing on Yayla et al. (2023), Javdan et al. (2024), and Ramkissoon (2023), comprises nine items that measure the multifaceted well-being of host communities. These items address economic well-being (e.g., improvements in household income linked to tourism), safety and security (feeling safe at all times), access to public services such as healthcare, and the perceived preservation of cultural traditions. Environmental quality is also assessed through perceptions of clean, unspoiled natural surroundings, while psychological satisfaction is captured via overall life-satisfaction statements. Respondents again use the five-point agreement scale to indicate their level of well-being.

Finally, the STG construct consists of five items adapted from Rasoolimanesh et al. (2020) and Spadaro et al. (2023). These items examine residents’ participation in formal governance processes, including opportunities for public monitoring of development projects, involvement in policy co-creation, and engagement in community-led environmental stewardship initiatives. The scale also measures transparency in decision-making and perceptions of equitable benefit distribution among community members. All governance items employ the same Likert response format, reflecting respondents’ views on the depth and fairness of tourism governance mechanisms.

We conducted a pilot test with 50 respondents to assess clarity, content, face validity, and internal consistency; no items required modification.

3.3. Data Collection

Data were collected between January and September 2024 using a mixed-mode survey (online and paper-and-pencil) administered at key tourism touchpoints (e.g., visitor centers and community halls) and via community organizations in three island tourism destinations in Aceh. Trained research assistants obtained informed consent, assured confidentiality, and achieved an overall response rate of 90.42% (1266 usable responses).

3.4. Data Analysis

Our data analysis proceeded using covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) using the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, 2012), adhering to the two-stage approach outlined by Kline (2016) and Byrne (2016). In the first stage, we evaluated the measurement model via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). We established reliability by ensuring that Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) values were 0.70 or higher, per Nunnally and Bernstein (1994). Convergent validity was established by retaining indicators with standardized loadings of 0.50 or higher and computed average variance extracted (AVE) values of 0.50 or higher for each latent construct, as Hair et al. (2010) suggest. To establish discriminant validity, we ensured that each construct’s AVE exceeded its squared correlations with other constructs (Fornell–Larcker’s criterion) and heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlation value of 0.85, as per Henseler et al. (2015). Overall model fit was judged using multiple indices, i.e., χ2/df of 3.0 or lower, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.08 or lower, comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) of 0.90 or higher, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) of 0.08 or lower, consistent with best practices in recent SEM guidelines (Byrne, 2016; Kline, 2016).

In the second stage, we specified and tested our structural model to estimate the direct effects (TALC → QoL, QoL → Governance, TALC → Governance) and the mediating role of QoL. To isolate the net effects of TALC dimensions on QoL and STG, age, sex, tenure, and island were included as observed covariates. Categorical variables (island, tenure) were dummy-coded, while age and sex (0 = female, 1 = male) were treated as continuous and binary predictors, respectively. Covariates were modeled as direct predictors of QoL and STG, following recommendations for controlling exogenous variables in CB-SEM (Little, 2013). All covariates were grand-mean-centered to mitigate multicollinearity (Enders, 2022). We employed bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to generate 95% confidence intervals for indirect effects, following the procedures outlined in Hayes (2017). The model fit for the structural model was evaluated using the same indices as the measurement model, and we reported R2 values to indicate the explanatory power.

Post hoc multigroup SEM was also conducted to test structural path invariance across islands. Path coefficients (TALC → QoL, QoL → STG, TALC → STG) were freely estimated in an unconstrained model and compared to a fully constrained model using a chi-square difference test (Byrne, 2016). It required prior measurement invariance testing across islands (Weh, Pulo Aceh, Simeulue) to ensure latent constructs (TALC, QoL, STG) were equivalent in structure and interpretation (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000).

Additionally, we examined multicollinearity among covariates predicting the latent variables in the structural model and within each Island group to ensure stable path estimates. The threshold value of variance inflation factors (VIFs) was fixed at less than 5 to indicate negligible multicollinearity (Fox & Weisberg, 2019; Hair et al., 2010).

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Profile of Respondents

A total of 1266 valid responses were included in the analysis. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and geographic characteristics of the sample. Participants were stratified across three island destinations: Weh (36.49%), Pulo Aceh (32.70%), and Simeulue (30.81%). The sex distribution was nearly balanced, with 51.18% of respondents being male and 48.82% female. The respondents represented a wide age range: 18–29 years (32.40%), 30–41 years (32.54%), 45–53 years (23.78%), and 54 years or older (9.48%). In terms of resident tenure, 22.12% were newcomers (<3 years), 44.63% had been established (i.e., lived in the community for 3–10 years), and 33.25% were long-term residents (>10 years).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

4.2. Preliminary Analysis

Before conducting the CFA, we examined the distributions and intercorrelations of our three composite constructs—TALC, QoL, and STG—as summarized in Table 2 to determine whether the data met or deviated from normality assumptions. Univariate normality was assessed via skewness and kurtosis for each construct score, with all absolute skewness values below 2.00 and absolute kurtosis values below 7.00 (West et al., 1995), indicating acceptable normality for CB-SEM. Furthermore, multivariate normality was evaluated using Mardia’s coefficient (Mardia’s skew = 8.80, p > 0.05; Mardia’s kurtosis = 0.17, p > 0.05), suggesting no serious departure from multivariate normality (Mardia, 1970; West et al., 1995).

Table 2.

Normality and correlation analysis results.

To assess potential common method bias, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test on all 28 TALC, QoL, and STG items (see Appendix B.1). An unrotated principal-axis EFA yielded a first-factor eigenvalue of 9.55, which accounted for 34.10% of the total variance—well below the 50% cutoff—indicating that common method bias is unlikely to be a serious concern in our data (Harman, 1976; Podsakoff et al., 2003).

4.3. Measurement Model

Having completed the preliminary analysis, we validated the measurement model via CFA. We first examined the reliability and convergent validity, as shown in Table 3. Cronbach’s alpha and CR values ranged from 0.86 to 0.94 across the three latent constructs, exceeding the 0.70 threshold and confirming reliability. All standardized factor loadings exceeded 0.50, statistically significant (p < 0.001), and the AVE values were above 0.50, supporting the convergent validity.

Table 3.

Reliability and convergent validity results.

Discriminant validity was then examined using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the HTMT ratio. It was supported: for each construct, the square root of its AVE exceeded its correlations with other constructs, as shown in Table 4, and the HTMT ratios were less than the conservative threshold of 0.85, as shown in Appendix B.2. Multicollinearity diagnostics also revealed that all VIF values were below 5, as shown in Appendix B.3.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity results (Fornell–Larcker criterion).

The measurement model demonstrated an excellent fit to the data (χ2(347) = 361.66, p = 0.28; CFI = 0.999; TLI = 0.999; RMSEA = 0.02 (90% CI: 0.00–0.01); SRMR = 0.02). The non-significant chi-square and values across all other indices met the established thresholds for a good fit, suggesting that the hypothesized factor structure is consistent with the observed data.

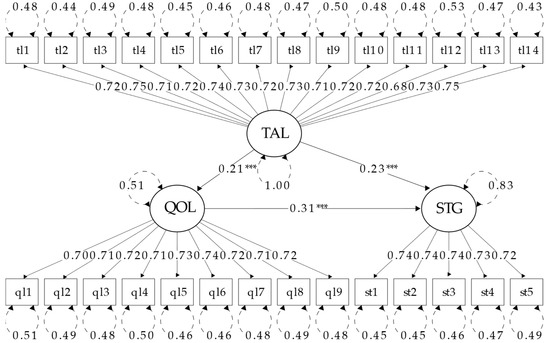

4.4. Structural Model

The structural model was evaluated to test the hypothesized relationships between TALC dimensions, resident Quality of Life (QoL), and Sustainable Tourism Governance (STG). The covariate-adjusted structural model exhibited excellent fit (χ2(347) = 361.66, p = 0.28; CFI = 0.999; TLI = 0.998; RMSEA = 0.01 (90% CI: 0.00–0.01); SRMR = 0.05). Path analysis results supported all four hypotheses, as shown in Table 5 and visualized in Figure 2.

Table 5.

Standardized path coefficients (with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals).

Figure 2.

Structural model diagram with standardized path coefficients. All paths are significant at p < 0.001 and QoL mediates the TALC–STG relationship. Note: *** p < 0.001. Covariates omitted for clarity.

TALC dimensions had a positive effect on residents’ QoL (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), supporting the first hypothesis, and had a direct, positive effect on STG (β = 0.23, p < 0.001), providing support for the third hypothesis. Resident’s QoL had a strong positive effect on STG (β = 0.31, p < 0.001), affirming the second hypothesis. Mediation analysis using bias-corrected bootstrapping (5000 resamples) revealed a statistically significant indirect effect of TALC on STG via QoL (β = 0.07, p < 0.001), confirming partial mediation and supporting the fourth hypothesis. The total effect of TALC on STG (direct + indirect) was β = 0.30.

Furthermore, resident tenure (β = 0.28–1.27, p < 0.001) and male sex (β = 0.36, p < 0.001) were significant predictors of QoL in this covariate-adjusted model, significantly enhancing QoL, while age had no significant effect (p = 0.81). Nonetheless, none of the covariates (i.e., island, tenure, sex, age) significantly predicted STG participation (all p > 0.40). The final model explained 49.0% of the variance in QoL (R2 = 0.49) and 17.4% of the variance in sustainable governance participation (R2 = 0.17).

These results indicate that TALC-driven development (e.g., infrastructure, stakeholder involvement) positively contributes to residents’ well-being and drives their engagement in sustainable tourism governance, both directly and through the mediating role of QoL. While statistically significant, the mediation effect accounted for a moderate portion (i.e., 22.4%) of the total effect, suggesting that QoL is a meaningful but not exclusive mechanism in this relationship.

Post hoc multigroup SEM was conducted to test structural path invariance across islands. It involved measurement invariance testing to ensure the TALC, QoL, and STG constructs held equivalent meaning across Weh, Pulo Aceh, and Simeulue. Nested model comparisons supported full scalar invariance, as shown in Table 6. Full scalar invariance (ΔCFI ≤ 0.01, p > 0.05), according to Cheung and Rensvold (2002), confirmed equivalent factor structures, loadings, and intercepts across islands, hence permitting valid cross-group comparisons (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016).

Table 6.

Nested model comparisons of measurement invariance.

Multigroup SEM analysis revealed an excellent fit across all groups (χ2(1147) = 1170.41, p = 0.31; CFI = 0.999; TLI = 0.998; RMSEA = 0.01; SRMR = 0.05). Furthermore, key hypothesized relationships were consistently held across islands (all p < 0.001), as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Standardized structural paths by group.

TALC dimensions (e.g., infrastructure, stakeholder involvement) significantly enhanced residents’ QoL across all islands, with standardized effects ranging from β = 0.33, p < 0.001 (Simeulue) to β = 0.35, p < 0.001 (Weh, Pulo Aceh). However, because mean TALC scores were statistically similar across the three islands, we cannot infer that the islands have substantively different life-cycle stages. Instead, higher perceived destination maturity, regardless of actual ‘stage’, is associated with better resident well-being. TALC dimensions also directly strengthened STG participation, independent of QoL. Effects were largest in Pulo Aceh (β = 0.25, p < 0.001) and smallest in Simeulue (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), suggesting that life cycle-driven infrastructure and stakeholder networks themselves incentivize governance involvement beyond improvements in the quality of life.

Higher QoL consistently predicted greater community participation in governance (STG), with effects most substantial in Pulo Aceh (β = 0.32) and weakest in Simeulue (β = 0.28) (p < 0.001). Consistent with social exchange theory (Gursoy et al., 2002; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2012) and Ramkissoon’s (2023) conceptual model of perceived social impacts → QoL → pro-environmental engagement, our data suggest that residents who experience tourism-linked economic and service benefits (e.g., improved income, healthcare access) exhibit higher participation in policy co-creation and environmental stewardship.

QoL also partially mediated the TALC-STG relationship in all groups, with indirect effects accounting for 30–35% of the total effect. For example, in Weh, 33.9% of TALC’s total impact on STG (β = 0.33) operated through QoL (indirect β = 0.10). Critically, multigroup invariance tests confirmed no significant differences in mediation strength across islands (Δχ2(2) = 3.12, p = 0.21), reinforcing the mechanism’s generalizability.

While multigroup SEM confirmed that structural path estimates were largely invariant across the three islands, minor variations in effect sizes are worth noting. Specifically, the influence of QoL on STG was slightly weaker in Simeulue (β = 0.28) than in Weh (β = 0.29) and Pulo Aceh (β = 0.32). These subtle differences may reflect local variation in governance history, civic norms, or expectations of resident involvement. For example, Liu-Lastres et al. (2020) found that in Simeulue, disaster recovery programs following the 2004 tsunami emphasized physical infrastructure over participatory planning, which may have shaped long-term perceptions of governance as externally driven. Such contextual factors, while beyond the scope of our current model, highlight the need to consider political culture and institutional memory in future comparative research.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study brought together Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC), resident quality of life (QoL), and sustainable tourism governance (STG) within a single structural equation modeling (SEM) framework, helping to fill an important gap in the literature on island destinations in the Global South. Our findings show that (1) higher TALC perceptions are associated with better residents’ QoL; (2) residents’ QoL positively relates to participation in governance; (3) there is a direct TALC–STG link; and (4) residents’ QoL partially mediates the TALC–STG relationship.

In the following sections, we interpret these results, situate them within existing theory, discuss practical and policy implications, acknowledge limitations, and outline avenues for future research.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

Our study applies and integrates existing frameworks, i.e., TALC diffusion, residents’ QoL impacts, and social exchange–governance links, into one SEM. To our knowledge, this is the first multi-island, Global-South study to simultaneously estimate direct and QoL-mediated TALC effects on governance participation. While Butler’s (1980) Tourism Area Life Cycle framed destinations as a visitor-growth curve, recent scholarships have urged situating TALC within broader socio-ecological systems (Ramón-Cardona & Sánchez-Fernández, 2024; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2020). In our multi-island, Global-South context, SEM results show that overall perceived destination maturity is positively associated with residents’ quality of life (β = 0.21, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that higher perceptions of destination development, reflected in locals’ evaluations of infrastructure adequacy, stakeholder coordination, and service provisions, coincide with reports of improved healthcare access, safety, and cultural preservation.

Unlike Rasoolimanesh et al. (2020), whose work primarily proposed sustainability indicator frameworks without testing structural pathways, our study operationalizes sustainable tourism governance as a multidimensional construct combining policy co-creation and stewardship actions and empirically models its determinants within a unified SEM framework. Furthermore, in contrast to Spadaro et al. (2023), who examined participatory planning in a European metropolitan setting, this research applies the framework in small-island destinations of the Global South, thereby extending the generalizability of TALC-linked governance models across diverse socio-cultural and geographic contexts.

Moreover, the direct association between TALC perceptions and STG (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) indicates that perceived destination maturity, such as transport and promotional developments, is linked to governance participation over and above QoL effects. This result complements prior scholarship (e.g., Chan et al., 2021; Spadaro et al., 2023) by showing that destination maturity perceptions can have governance implications independent of host well-being.

5.2. Implications for Sustainable Tourism Governance

Our multigroup analyses reveal consistent patterns across the Weh, Pulo Aceh, and Simeulue islands, suggesting that the TALC–QoL–STG framework holds across our three Acehnese islands. Tourism planners should integrate mandatory feedback loops, such as community advisory boards or digital participatory platforms to channel resident insights into policy co-creation. Such hybrid 4P governance structures (public–private–people partnerships) can institutionalize oversight and strengthen long-term support (Spadaro et al., 2023).

Furthermore, the strong effect of QoL on sustainable tourism governance (β = 0.31, p < 0.001) highlights the strategic role of well-being investments in unlocking civic capital. Destination managers might prioritize targeted infrastructure upgrades, particularly in underperforming domains such as healthcare and community education programs, focusing on environmental stewardship and decision-making literacy. Stakeholders can reinforce the QoL-STG feedback loop by linking QoL-related initiatives to tangible governance opportunities (e.g., training residents in environmental monitoring).

5.3. Policy and Managerial Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, we offer four practical recommendations for destination managers. First, destination managers might consider pursuing a continuous program of strategic infrastructure investment that equally prioritizes tourist amenities, critical resident services, and coastal-climate-resilient infrastructure. Rather than targeting a single development phase, resources should be allocated throughout the destination’s maturation to strengthen healthcare provision (e.g., reliable clinics and emergency response systems), implement robust marine waste treatment and coastal erosion defenses, and enhance basic utilities. By closing these quality-of-life gaps, managers create the conditions for residents to experience tangible benefits from tourism development, which our SEM demonstrates is closely linked to greater civic participation.

Second, establishing inclusive, context-appropriate participatory governance platforms is equally essential. In settings where internet connectivity is limited, simple SMS-based feedback systems can ensure that even the most remote island community members can report concerns and suggest improvements. Interactive web dashboards or formal community advisory boards can provide real-time transparency around tourism metrics and decision-making processes on islands with broader digital infrastructure. Such mechanisms not only deepen accountability but also send a clear signal that resident voices are integral to policy co-creation.

Third, a capacity-building program must equip locals with the skills necessary for environmental monitoring, cultural heritage protection, and policy analysis to translate these procedural innovations into effective practice. Tailored training, whether in coral-reef assessment, cultural site stewardship, or tsunami-resilient planning, empowers community members to move beyond passive consultation toward active governance roles. This empowerment reinforces the feedback loop we identified, whereby improvements in resident quality of life catalyze stronger engagement in sustainable tourism governance.

Fourth, overcoming the constraints of small-island scale demands cross-island collaboration. Regular inter-island forums, shared resource initiatives (e.g., joint waste-processing facilities for nearby islands), and peer-learning exchanges allow communities to pool expertise, disseminate best practices, and develop region-wide strategies for sustainable tourism. By learning from one another’s experiences, island destinations can better navigate the continuous cycle of development, well-being, and governance that underpins long-term resilience.

5.4. Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. Its cross-sectional design precludes causal inference; longitudinal SEM work is needed to observe how changes in perceived destination maturity relate to shifts in quality of life and governance engagement over time. Reliance on self-reported measures may introduce social desirability bias; future research should seek objective measures (e.g., healthcare utilization rates or records of attendance at governance meetings) to validate self-reports. Furthermore, although our sample spans three Acehnese islands, findings may not extend to larger, more urbanized, or non-tropical settings; replication in continental and temperate contexts would bolster external validity.

Nevertheless, we see several promising avenues for further study. Future studies could incorporate additional constructs such as institutional trust, civic identity, and political efficacy, which have been shown to shape residents’ willingness to engage in governance processes. Examining these factors alongside perceived destination maturity and quality of life could yield a more comprehensive understanding of the antecedents of sustainable tourism governance.

First, longitudinal panel surveys could capture the evolving perceptions of tourism development influence well-being and participation. Second, integrating environmental impact metrics (e.g., biodiversity indices or water quality measures) would enrich the social-ecological scope of TALC research. Third, researchers could examine how e-participation platforms or GIS-enabled monitoring tools moderate the link between quality of life and governance engagement. Finally, comparative work between Global-North and Global-South destinations could reveal institutional or cultural factors that shape these dynamics.

Additionally, our structural model explains 17.4% of the variance in sustainable tourism governance (STG), suggesting that other unmeasured factors may also be influential. Future research could explore the roles of institutional trust, civic identity, political efficacy, historical grievances, or prior experience with tourism governance. Incorporating these constructs may help capture deeper socio-political determinants of community participation beyond perceived QoL and TALC dimensions.

5.5. Conclusions

This study contributes to tourism-governance scholarship by integrating perceptions of destination maturity, resident quality of life, and sustainable-tourism governance within a single SEM framework. Our results show that higher perceived destination development is directly and indirectly associated with improved quality of life, with greater resident participation in governance. These findings offer an empirically grounded, contextually adaptable model for destination managers: by enhancing the infrastructure and services that underpin local well-being, stakeholders can simultaneously lay the groundwork for more robust, participatory governance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.K., R.D.P. and M.R.S.; data curation, T.M.K.; formal analysis, T.M.K., R.D.P., M.R.S., R.H. and A.M.; funding acquisition, T.M.K.; methodology, T.M.K., R.D.P. and M.R.S.; project administration, T.M.K., R.D.P., M.R.S., R.H. and A.M.; supervision, T.M.K.; writing—original draft, T.M.K., R.D.P. and M.R.S.; writing—review and editing, T.M.K., R.D.P., M.R.S., R.H. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by LPPM Universitas Syiah Kuala, grant no. 10760.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universitas Syiah Kuala (protocol code 10760, dated 12 December 2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/cpx8r/?view_only=473c0d5bf8c34e15a706df6ec0946869 (accessed on 22 May 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the island residents who participated in this study and to the community organizations that hosted some of the meetings; their valuable insights and engagement were instrumental in exploring the tourism area life cycle, quality of life, and sustainable tourism governance. Furthermore, we acknowledge the essential contributions of our colleagues in the Faculty of Economics and Business, whose guidance and expertise significantly enhanced the quality of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the study’s design; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CB-SEM | Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–Monotrait |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square of Error Approximation |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| STG | Sustainable Tourism Governance |

| TALC | Tourism Area Life Cycle |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Full questionnaire items and source attribution.

Table A1.

Full questionnaire items and source attribution.

| Item | Indicator | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Construct: Tourism Area Life Cycle | ||

| tl1 | The growth rate of tourist arrivals | Butler (1980) |

| tl2 | Development of accommodation facilities | Kedang and Soesilo (2021) |

| tl3 | Quality of transportation infrastructure | Kedang and Soesilo (2021) |

| tl4 | Intensity of destination marketing and promotion | Gore et al. (2024) |

| tl5 | Government policy support and regulation | Gore et al. (2024) |

| tl6 | Local community participation initiatives | Gore et al. (2024) |

| tl7 | Private-sector investment levels | Gore et al. (2024) |

| tl8 | Diversification of tourism products | Kedang and Soesilo (2021) |

| tl9 | Innovation in tourism services | Gore et al. (2024) |

| tl10 | Adoption of environmental management practices | Kedang and Soesilo (2021) |

| tl11 | Promotion and preservation of cultural heritage | Gore et al. (2024) |

| tl12 | Monitoring of carrying capacity | Gore et al. (2024) |

| tl13 | Management of tourism seasonality | Kedang and Soesilo (2021) |

| tl14 | Destination rejuvenation and adaptive planning | Gore et al. (2024) |

| Construct: Residents’ Quality of Life | ||

| ql1 | Perceived economic well-being | Yayla et al. (2023) |

| ql2 | Satisfaction with public infrastructure | Javdan et al. (2024) |

| ql3 | Sense of safety and community security | Yayla et al. (2023) |

| ql4 | Access to healthcare services | Javdan et al. (2024) |

| ql5 | Social cohesion and community pride | Ramkissoon (2023) |

| ql6 | Perceived cultural integrity and preservation | Javdan et al. (2024) |

| ql7 | Environmental quality (e.g., clean water, clean air) | Yayla et al. (2023) |

| ql8 | Psychological well-being (stress-free, life satisfaction) | Ramkissoon (2023) |

| ql9 | Employment stability and income security | Javdan et al. (2024) |

| Construct: Sustainable Tourism Governance | ||

| st1 | Public participation in monitoring tourism development | Rasoolimanesh et al. (2020) |

| st2 | Opportunities for policy co-creation | Rasoolimanesh et al. (2020) |

| st3 | Initiatives for environmental stewardship | Spadaro et al. (2023) |

| st4 | Transparency in decision-making processes | Spadaro et al. (2023) |

| st5 | Equitable distribution of tourism benefits | Rasoolimanesh et al. (2020) |

Appendix A.2

Table A2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table A2.

Descriptive statistics.

| Item | Construct | Mean | SD | Item | Construct | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tl1 | TALC | 3.17 | 0.65 | ql1 | QoL | 2.91 | 0.65 |

| tl2 | TALC | 2.88 | 0.70 | ql2 | QoL | 2.93 | 0.59 |

| tl3 | TALC | 3.12 | 0.69 | ql3 | QoL | 3.16 | 0.69 |

| tl4 | TALC | 2.81 | 0.65 | ql4 | QoL | 2.78 | 0.63 |

| tl5 | TALC | 2.86 | 0.74 | ql5 | QoL | 3.06 | 0.71 |

| tl6 | TALC | 2.79 | 0.70 | ql6 | QoL | 2.98 | 0.73 |

| tl7 | TALC | 3.15 | 0.69 | ql7 | QoL | 3.09 | 0.64 |

| tl8 | TALC | 3.13 | 0.72 | ql8 | QoL | 2.99 | 0.65 |

| tl9 | TALC | 2.92 | 0.69 | ql9 | QoL | 3.15 | 0.69 |

| tl10 | TALC | 3.01 | 0.65 | st1 | STG | 2.87 | 0.69 |

| tl11 | TALC | 2.95 | 0.66 | st2 | STG | 3.12 | 0.75 |

| tl12 | TALC | 3.21 | 0.67 | st3 | STG | 3.00 | 0.66 |

| tl13 | TALC | 2.97 | 0.74 | st4 | STG | 2.96 | 0.72 |

| tl14 | TALC | 2.74 | 0.74 | st5 | STG | 2.94 | 0.65 |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1

Table A3.

Unrotated Principal-Axis EFA: Eigenvalues and % variance explained.

Table A3.

Unrotated Principal-Axis EFA: Eigenvalues and % variance explained.

| Factor | Eigenvalue | Proportion | Factor | Eigenvalue | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.546 | 0.341 | 15 | 0.471 | 0.017 |

| 2 | 4.247 | 0.152 | 16 | 0.461 | 0.016 |

| 3 | 2.466 | 0.088 | 17 | 0.458 | 0.016 |

| 4 | 0.604 | 0.022 | 18 | 0.447 | 0.016 |

| 5 | 0.583 | 0.021 | 19 | 0.447 | 0.016 |

| 6 | 0.572 | 0.020 | 20 | 0.430 | 0.015 |

| 7 | 0.557 | 0.020 | 21 | 0.427 | 0.015 |

| 8 | 0.540 | 0.019 | 22 | 0.411 | 0.015 |

| 9 | 0.535 | 0.019 | 23 | 0.403 | 0.014 |

| 10 | 0.519 | 0.019 | 24 | 0.396 | 0.014 |

| 11 | 0.508 | 0.018 | 25 | 0.386 | 0.014 |

| 12 | 0.497 | 0.018 | 26 | 0.386 | 0.014 |

| 13 | 0.496 | 0.018 | 27 | 0.371 | 0.013 |

| 14 | 0.483 | 0.017 | 28 | 0.354 | 0.014 |

Appendix B.2

Table A4.

Discriminant validity (HTMT ratio).

Table A4.

Discriminant validity (HTMT ratio).

| Construct | TALC | QoL | STG |

|---|---|---|---|

| TALC | – | ||

| QoL | 0.34 | – | |

| STG | 0.33 | 0.38 | – |

Appendix B.3

Table A5.

Multicollinearity diagnostics.

Table A5.

Multicollinearity diagnostics.

| Dependent | Predictor | VIF | Dependent | Predictor | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QOL_est | islandSimeulue | 1.33 | STG_est | islandSimeulue | 1.33 |

| islandPuloAceh | 1.43 | islandPuloAceh | 1.43 | ||

| tenureestablished | 1.73 | tenureestablished | 1.73 | ||

| tenurelong_term | 4.13 | tenurelong_term | 4.13 | ||

| sex | 1.37 | sex | 1.37 | ||

| age | 3.37 | age | 3.37 |

References

- Agarwal, S. (2002). Restructuring seaside tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, F., Guerreiro, M., Pinto, P., & Ghaderi, Z. (2024). From tourist experience to satisfaction and loyalty: Exploring the role of a sense of well-being. Journal of Travel Research, 63(8), 1989–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Q. B., Shah, S. N., Iqbal, N., Sheeraz, M., Asadullah, M., Mahar, S., & Khan, A. U. (2023). Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(3), 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, T. (1998). Taking the exit route: Extending the tourism area life cycle model. Current Issues in Tourism, 1(2), 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. W. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implication for management of resources. Canadian Geographies, 24(1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. W. (2009). Tourism destination development: Cycles and forces, myths and realities. Tourism Recreation Research, 34(3), 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J. K. L., Marzuki, K. M., & Mohtar, T. M. (2021). Local community participation and responsible tourism practices in ecotourism destination: A case of Lower Kinabatangan, Sabah. Sustainability, 13(23), 13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, P. T., Feener, R. M., & Reid, A. (Eds.). (2012). From the ground up: Perspective on post-tsunami and post-conflict aceh. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Diedrich, A., & García-Buades, E. (2009). Local perceptions of tourism as indicators of destination decline. Tourism Management, 30(4), 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R., & Graci, S. (2012). Sustainable tourism in island destinations. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C. K. (2022). Applied missing data analysis (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G., & Encontre, P. (1998). The economic disadvantages of island developing countries: Problems of smallness, remoteness and economies of scale. In G. Baldacchino, & R. Greenwood (Eds.), Competing strategies of socio-economic development for small islands (pp. 69–87). Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J., & Weisberg, S. (2019). An R companion to applied regression (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Garay, L., & Cànoves, G. (2011). Life cycles, stages and tourism history. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(2), 651–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, S., Borde, N., & Hegde Desai, P. (2024). Mapping tourism strategy patterns on tourism area life cycle. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(1), 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D., Jurowski, C., & Uysal, M. (2002). Resident attitudes. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (Eds.). (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, L. (2024, September 26). The summer that tourism fell apart. BBC. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20240925-the-summer-that-tourism-fell-apart (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Hampton, M. P., & Jeyacheya, J. (2015). Power, ownership and tourism in small islands: Evidence from Indonesia. World Development, 70, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis (3rd ed.). The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W., Chen, C.-Y., & Fu, Y.-K. (2022). The sustainable island tourism evaluation model using the FDM-DEMATEL-ANP method. Sustainability, 14(12), 7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javdan, M., Jafarpour Ghalehteimouri, K., Soleimani, M., & Pavee, S. (2024). Community attitudes toward tourism and quality of life: A case study of Palangan village, Iran. Discover Environment, 2(1), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasuriya, S., & McCawley, P. T. (2010). The Asian Tsunami: Aid and reconstruction after a disaster. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kedang, R. N. M., & Soesilo, N. I. (2021). Sustainable tourism development strategy in Bintan regency based on tourism area life cycle. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 716(1), 012138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantopoulou, C., Varelas, S., & Liargovas, P. (2024). Well-being and tourism: A systematic literature review. Economies, 12(10), 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu-Lastres, B., Mariska, D., Tan, X., & Ying, T. (2020). Can post-disaster tourism development improve destination livelihoods? A case study of Aceh, Indonesia. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M., & Hassink, R. (2013). An evolutionary perspective on tourism area development. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardia, K. V. (1970). Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika, 57(3), 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T. (2022). Tourism sustainability paradigm. In D. Buhalis (Ed.), Encyclopedia of tourism management and marketing (pp. 482–484). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Thi, H., Nguyen Thi, T., Vu Trong, T., Nguyen Duc, T., & Nguyen Nghi, T. (2024). Sustainable tourism governance: A study of the impact of culture. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 13(2), 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2012). Power, trust, social exchange and community support. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 997–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Peypoch, N., Song, Y., Tan, R., & Zhang, L. (2024). Tourism efficiency and quality of life in Chinese cities. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 10(4), 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. (2023). Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Cardona, J., & Sánchez-Fernández, M. D. (2024). The consolidation stage of the Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model: The case of Ibiza from 1977 to 2000. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(1), 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Ramakrishna, S., Hall, C. M., Esfandiar, K., & Seyfi, S. (2020). A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1497–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindrasih, E. (2019). Life after tsunami: The transformation of a post-tsunami and post-conflict tourist destination: The case of halal tourism, Aceh, Indonesia. International Development Planning Review, 41(4), 517–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R., & Momsen, J. H. (2008). Tourism and poverty reduction: Issues for small island states. Tourism Geographies, 10(1), 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, I., Pirlone, F., Bruno, F., Saba, G., Poggio, B., & Bruzzone, S. (2023). Stakeholder participation in planning of a sustainable and competitive tourism destination: The Genoa integrated action plan. Sustainability, 15(6), 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, E. L., & Adger, W. N. (2004). Does adaptive management of natural resources enhance resilience to climate change? Ecology and Society, 9(2). Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267677 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- UNWTO. (2017). Tourism and the sustainable development goals: Journey to 2030. UNWTO. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M., Sirgy, M. J., Woo, E., & Kim, H. (2016). Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tourism Management, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), 4–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgger, M., & Pechlaner, H. (2014). Requirements for destination management organizations in destination governance: Understanding DMO success. Tourism Management, 41, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D. B. (2012). Organic, incremental and induced paths to sustainable mass tourism convergence. Tourism Management, 33(5), 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S. G., Finch, J. F., & Curran, P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 56–75). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Westland, J. C. (2010). Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 9(6), 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanes, A., Zielinski, S., Diaz Cano, M., & Kim, S. (2019). Community-based tourism in developing countries: A framework for policy evaluation. Sustainability, 11(9), 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayla, Ö., Koç, B., & Dimanche, F. (2023). Residents’ support for tourism development: Investigating quality-of-life, community commitment, and communication. European Journal of Tourism Research, 33, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).