Dissecting the Economics of Tourism and Its Influencing Variables—Facts on the National Capital City (IKN)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Approach and Data

2.2. Constructed Variables

2.3. Analytical Tools and Econometric Models

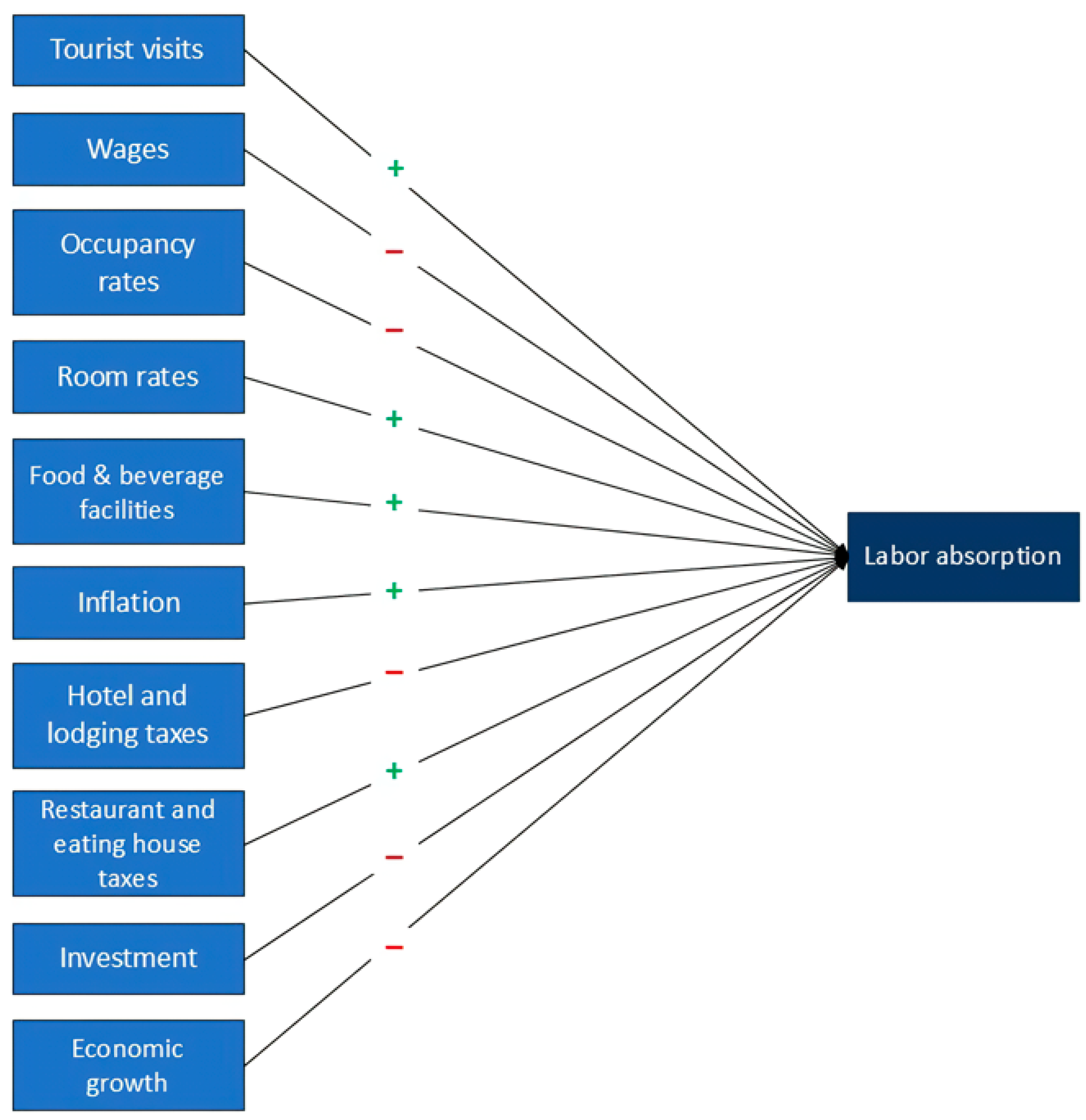

- First model

- Null hypothesis (H0): Tourist visits, wages, economic growth, occupancy rates, room rates, food and beverage facilities, inflation, hotel and lodging taxes, restaurant and eating-house taxes, and investment significantly influence labor absorption;

- Alternative hypothesis (Ha): Tourist visits, wages, economic growth, occupancy rates, room rates, food and beverage facilities, inflation, hotel and lodging taxes, restaurant and eating-house taxes, and investment have insignificant influences on labor absorption.

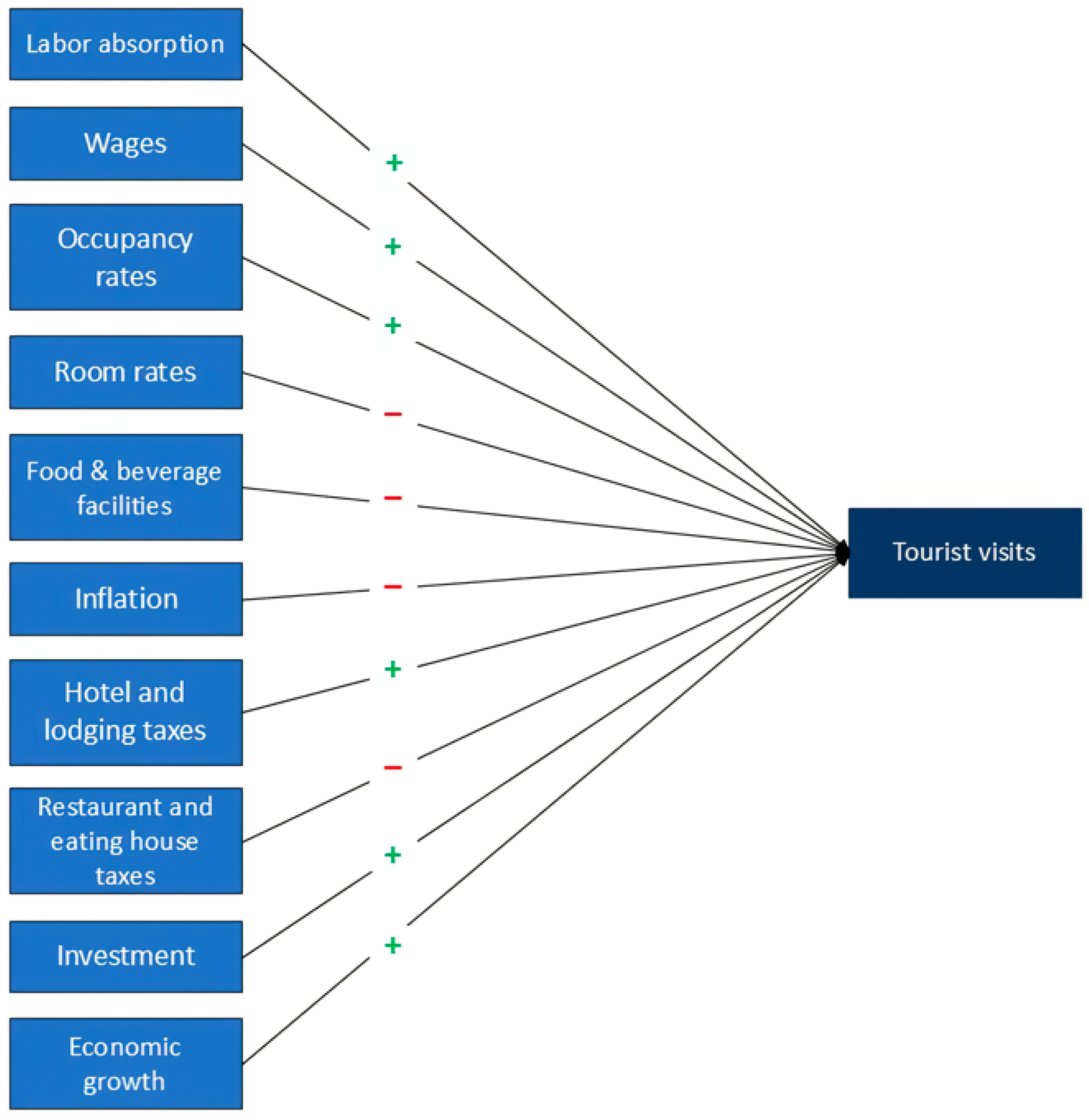

- Second model

- Null hypothesis (H0): Investment, inflation, occupancy rates, room rates, food and beverage facilities, labor absorption, hotel and lodging taxes, restaurant and eating-house taxes, economic growth, and wages significantly influence tourist visits;

- Alternative hypothesis (Ha): Investment, inflation, occupancy rates, room rates, food and beverage facilities, labor absorption, hotel and lodging taxes, restaurant and eating-house taxes, economic growth, and wages have insignificant influences on tourist visits.

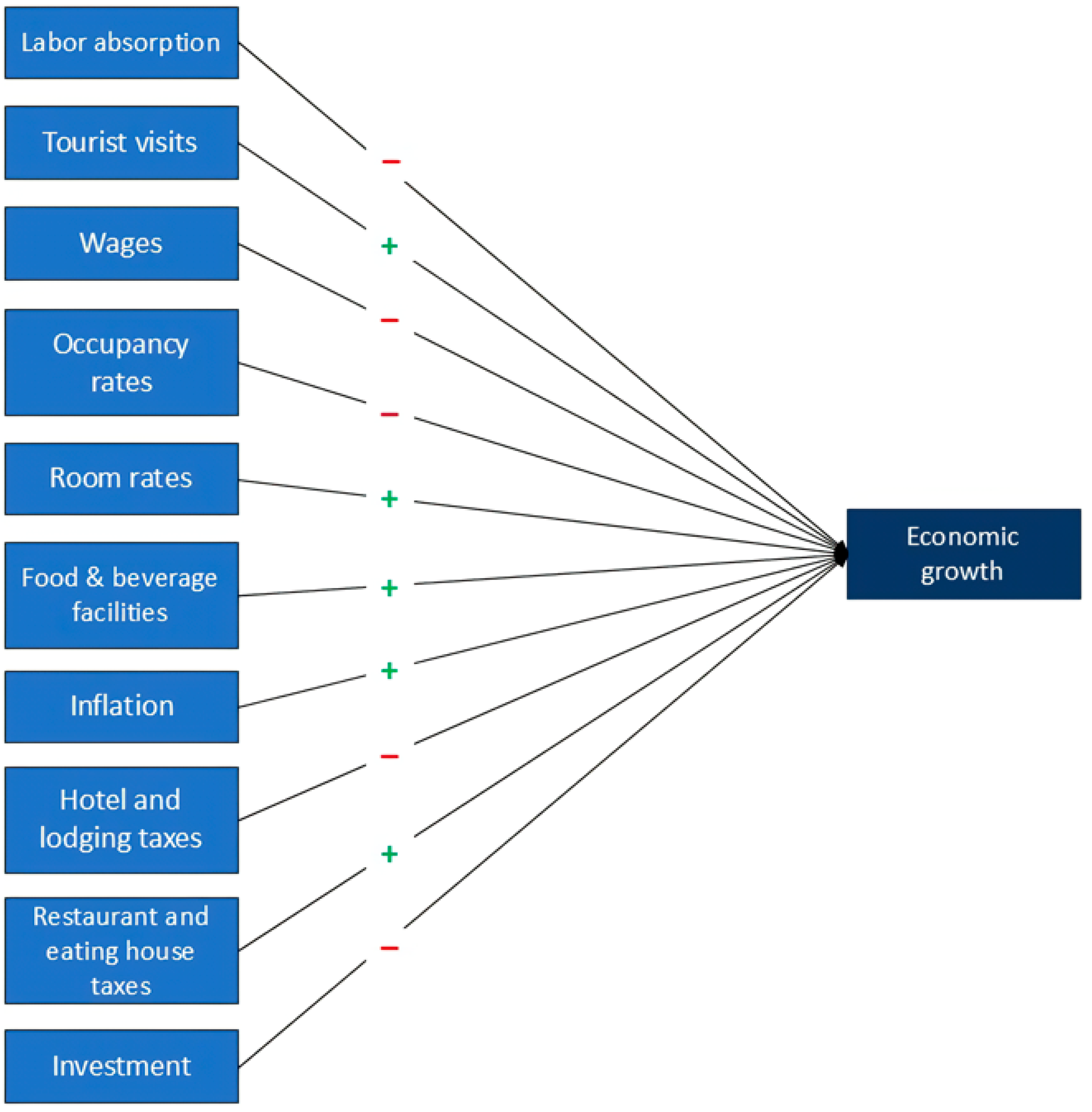

- Third model

- Null hypothesis (H0): Tourist visits, wages, occupancy rates, room rates, food and beverage facilities, labor absorption, hotel and lodging taxes, restaurant and eating-house taxes, inflation, and investment significantly influence economic growth;

- Alternative hypothesis (Ha): Tourist visits, wages, occupancy rates, room rates, food and beverage facilities, labor absorption, hotel and lodging taxes, restaurant and eating-house taxes, inflation, and investment have insignificant influences economic growth.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Normality Test of the Data

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.4. Regression Testing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASEAN | Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| BPS | Badan Pusat Statistik/Central Statistics Office |

| BRICS | Brazil, Rusia, India, China, and South Africa |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CPI | Consumer Price Index |

| DPR | Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat/House of Representatives |

| FDI | Foreign Direct Investment |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GRDP | Gross Regional Domestic Product |

| IDR | Indonesian Rupiah |

| IKN | Ibu Kota Negara/National Capital City |

| K-S | Kolmogorov–Smirnov |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OIC | Organization of Islamic Cooperation |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| PPU | Penajam Paser Utara |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TPAK | Tingkat Partisipasi Angkatan Kerja/Labor Force Participation Rate |

| UMK | Upah Minimum Kabupaten/District Minimum Wage |

| USA | United States of America |

References

- Aburumman, A. H., Malkawi, M. S., Lkurdi, B. H. A., & Alshamaileh, M. O. (2018). Tourist perception toward food and beverage service quality and its impact on behavioral intention: Evidence from eastern region hotels in Emirate of Sharjah in United Arab Emirates. European Journal of Social Sciences, 56(3), 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Achmad, F., & Wiratmadja, I. I. (2024). Strategic advancements in tourism development in Indonesia: Assessing the impact of facilities and services using the PLS-SEM approach. Journal Industrial Servicess, 10(1), 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Aida, N., Atiqasani, G., & Palupi, W. A. (2024). The effect of the tourism sector on economic growth in Indonesia. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, 21, 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaş, S. G., Yüncü, D., & Kantar, Y. M. (2017). Spatial distribution of occupancy rate in the hospitality sector in Turkey according to international and domestic tourist arrivals. In A. Saufi, I. Andilolo, N. Othman, & A. Lew (Eds.), Balancing development and sustainability in tourism destinations. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Anggraeni, G. N. (2017). The relationship between numbers of international tourist arrivals and economic growth in the ASEAN-8: Panel data approach. Journal of Developing Economies, 2(1), 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apriyanti, M. E., Sumaryoto, S., & Meirinaldi, M. (2024). The importance of tourism infrastructure in increasing domestic and international tourism. International Journal of Research in Vocational Studies, 3(4), 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S. D., & Mathur, S. (2020). Hotel pricing at tourist destinations—A comparison across emerging and developed markets. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, S. A., Alola, U. V., Ghasemi, M., & Alola, A. A. (2020). The (Un)sticky role of exchange and inflation rate in tourism development: Insight from the low and high political risk destinations. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(12), 1670–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizurrohman, M., Hartarto, R. B., Lin, Y.-M., & Nahar, F. H. (2021). The role of foreign tourists in economic growth: Evidence from Indonesia. Jurnal Ekonomi & Studi Pembangunan, 22(2), 313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Baral, R., & Rijal, D. P. (2022). Visitors’ impacts on remote destinations: An evaluation of a Nepalese mountainous village with intense tourism activity. Heliyon, 8(8), e10395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnet, E. M. (1975). The impact of inflation on the travel market. The Tourist Review, 30(1), 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellboy, M. (2024). Perbedaan taman safari dan kebun binatang, apa saja? [In English: What are the differences between a safari park and a zoo?]. Available online: https://www.traveloka.com/id-id/explore/destination/perbedaan-taman-safari-dan-kebun-binatang-acc/430715 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Berdenov, Z., Kakimzhanov, Y., Arykbayeva, K., Assylbekov, K., Wendt, J. A., Kaimuldinova, K. D., Beketova, A., Ataeva, G., & Kara, T. (2024). Sustainable development of the infrastructure of the city of Astana since the establishment of the capital as a factor of tourism development. Sustainability, 16(24), 10931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertan, S. (2020). Impact of restaurants in the development of gastronomic tourism. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 21, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPS-Statistics of East Kalimantan Province. (2025). Kalimantan Timur Province in figures 2025. Available online: https://kaltim.bps.go.id/id/publication/2025/02/28/2fd1ffbcf042aa223f3b9b25/kalimantan-timur-province-in-figures-2025.html (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- BPS-Statistics of Penajam Paser Utara Regency. (2025). Penajam Paser Utara Regency in figures 2025. Available online: https://ppukab.bps.go.id/id/publication/2025/02/28/22fa55d38e24319dbc765214/kabupaten-penajam-paser-utara-dalam-angka-2025.html (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Cahyoputra, L. A. L., & Febrianna, A. R. (2024). Tourism and creative economy sector participates in increasing investment in IKN. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/id/en/media-centre/infrastructure-news/march-2024/tourism-and-creative-economy-sector-participates-in-increasing-i.html (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Carpio, N. M., Napod, W., & Do, H. W. (2021). Gastronomy as a factor of tourists’ overall experience: A study of Jeonju, South Korea. International Hospitality Review, 35(1), 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-García, P. J., Brida, J. G., & Segarra, V. (2024). Modeling the link between tourism and economic development: Evidence from homogeneous panels of countries. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatibura, D. M. (2025). A hedonic analysis of the determinants of hotel room rates in the Greater Gaborone Region (Botswana) using quantile regression. International Hospitality Review, 39(1), 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-H. (2010). The economy, tourism growth and corporate performance in the Taiwanese hotel industry. Tourism Management, 31(5), 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-H. (2011). The response of hotel performance to international tourism development and crisis events. International journal of Hospitality Management, 30(1), 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V., & Costa, C. (2024). Tourism, economic development and the corporate performance of the hospitality industry: An empirical study of Portuguese tourism regions. European Journal of Tourism Research, 38, 3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descals-Tormo, A., & Ruiz-Tamarit, J.-R. (2022). Tourist choice, competitive tourism markets and the effect of a tourist tax on prducers revenues. Tourism Economics, 30(2), 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, T., McGinley, S., & Self, T. (2024). Hospitality industry attraction: The effect of job openings and employee wages in the United States. Tourism Management, 103, 104888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorta-González, P., & González-Betancor, S. M. (2021). Employment in tourism industries: Are there subsectors with a potentially higher level of income? Mathematics, 9(22), 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Román, J. L., Cárdenas-García, P. J., & Pulido-Fernández, J. I. (2021). Tourist tax to improve sustainability and the experience in mass tourism destinations: The case of Andalusia (Spain). Sustainability, 13(1), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elders, S. (2025). Tourism breaks records, scarcity in hotels: Opportunities for investors in hotel real estate. Available online: https://www.cbre.com/insights/viewpoints/tourism-breaks-records-scarcity-in-hotels-opportunities-for-investors-in-hotel-real-estate (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Elgin, C., & Elveren, A. Y. (2024). Unpacking the economic impact of tourism: A multidimensional approach to sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 478, 143947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Menyari, M. (2021). Effect of tourism FDI and international tourism to the economic growth in Morocco: Evidence from ARDL bound testing approach. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 13(2), 222–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enilov, M., & Wang, Y. (2021). Tourism and economic growth: Multi-country evidence from mixed-frequency Granger causality tests. Tourism Economics, 28(5), 1216–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzsebet, I. (2024). Examining the contribution of tourism to employment in the European Union. Journal of Tourism Theory and Research, 10(2), 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzel, S. (2021). FDI and tourism futures: A dynamic investigation for a panel of small island economies. Journal of Tourism Futures, 7(1), 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialho, D., & Van Bergeijk, P. A. G. (2017). The proliferation of developing country classifications. The Journal of Development Studies, 53(1), 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Firgo, M. (2025). Price effects and pass-through of a VAT increase on restaurants in Germany: Causal evidence for the first months and a mega sports event. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriadi, F., Priyagus, P., & Darma, D. C. (2023). Assessing the economic feasibility of tourism around IKN: Does it beyond the SDG standards? Indonesian Journal of Tourism and Leisure, 4(2), 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glawe, L., & Wagner, H. (2024). Inflation and inequality: New evidence from a dynamic panel threshold analysis. International Economics and Economic Policy, 21(2), 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackbarth, T. X., & de Vries, W. T. (2021). An evaluation of massive land interventions for the relocation of capital cities. Urban Science, 5(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T. T. P. (2023). The role of foreign direct investment in boosting tourism development: A study of Vietnam for 1990–2020 Interval. In A. T. Nguyen, T. T. Pham, J. Song, Y. L. Lin, & M. C. Dong (Eds.), Contemporary economic issues in Asian countries: Proceeding of CEIAC 2022, Volume 1. CEIAC 2022. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Huseynli, B. (2024). The effect of tourism revenues and inflation on economic growth in Balkan countries. Economic Studies Journal, 33(1), 150–165. [Google Scholar]

- Indriani, D. (2022). Tourism and economic growth: Evidence from ASEAN countries. Journal of Indonesian Applied Economics, 10(2), 100–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlban, M. O., & Liceli, M. T. (2022). The causal relationship of tourism development, economic growth, and firm performance: An analysis of the food and beverage industry. Journal of Tourism Leisure and Hospitality, 4(2), 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantzi, O., Tsiotas, D., & Polyzos, S. (2016). The contribution of tourism in national economies: Evidence of Greece. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 5(5), 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kalenjuk Pivarski, B., Tešanović, D., Šmugović, S., Ivanović, V., Paunić, M., Vuković Vojnović, D., Vujasinović, V., & Gagić Jaraković, S. (2024). Gastronomy as a predictor of tourism development—Defining food-related factors from the perspective of hospitality and tourism employees in Srem (A.P. Vojvodina, R. Serbia). Sustainability, 16(24), 10834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, U., Okafor, L. E., & Shafiullah, M. (2019). The effects of economic and financial crises on international tourist flows: A cross-country analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 59(2), 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., Bibi, S., Lorenzo, A., Lyu, J., & Babar, Z. U. (2020). Tourism and development in developing economies: A policy implication perspective. Sustainability, 12(4), 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, H. A., Szyf, Y. A., & Arnold, D. (2012). Construction and analysis of a global GDP growth model for 185 countries through 2050. Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies, 4(2), 91–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjánsdóttir, H. (2021). Tax on tourism in Europe: Does higher value-added tax (VAT) impact tourism demand in Europe? Current Issues in Tourism, 24(6), 738–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, A., & Fathoni, M. A. (2023). Increasing economic growth through halal tourism in Indonesia. Peusijuek Journal of Islamic Culture and Ethics, 1(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K. X., Jin, M., & Shi, W. (2018). Tourism as an important impetus to promoting economic growth: A critical review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W. L. (2024). Tourism and economic growth: Assessing the significance of sustainable competitiveness using a dynamic panel data approach. International Journal of Tourism Research, 26(5), e2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-X., Chen, M.-H., & Lu, L. (2021). The impact of international tourism on hotel sales performance: New proposals and evidence. Tourism Economics, 28(6), 1480–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S. W. (2020). Accommodation employment growth and volatility: Welcome aboard for a rocky ride. Tourism Economics, 27(8), 1820–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhumini, T. R. P. (2024). Impact of tourism employment on economic growth. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation, XI(III), 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahangila, D., & Anderson, W. (2017). Tax administrative burdens in the tourism sector in Zanzibar: Stakeholders’ perspectives. SAGE Open, 7(4), 21582440177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F., Wei, L., Asif, M., Haq, M. Z., & Rehman, H. (2019). The contribution of sustainable tourism to economic growth and employment in Pakistan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, M. S., Chowdhury, M. A. F., Shaikh, G. M., Ali, M., & Sheikh, S. M. (2018). Asymmetric impact of oil prices, exchange rate, and inflation on tourism demand in Pakistan: New evidence from nonlinear ARDL. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(4), 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, O. (2020). The innovation-employment nexus: An analysis of the impact of Airbnb on hotel employment. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 11(3), 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy of Indonesia. (2025). Geliat sektor pariwisata pacu pertumbuhan ekonomi [In English: Tourism boosts economic growth]. Available online: https://indonesia.go.id/kategori/editorial/9026/geliat-sektor-pariwisata-pacu-pertumbuhan-ekonomi?lang=1 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Mitra, S. K. (2020). An analysis of asymmetry in dynamic pricing of hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 89, 102406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, R. K. (2024). Economic contribution and employment opportunities of tourism and hospitality sectors. In A. I. Hunjra, & A. Sharma (Eds.), The emerald handbook of tourism economics and sustainable development (building the future of tourism) (pp. 293–306). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Mulet-Forteza, C., Ferrer-Rosell, B., Cunill, O. M., & Linares-Mustar’os, S. (2024). The role of expansion strategies and operational attributes on hotel performance: A compositional approach. arXiv, arXiv:2411.04640. [Google Scholar]

- Negara, S. D., & Rebecca, N. H. Y. (2024). The Nusantara project in progress: Risks and challenges. ISEAS Perspective, No. 59. Available online: https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/ISEAS_Perspective_2024_59.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Nguyen, P. C., Schinckus, C., Chong, F. H. L., Nguyen, B. Q., & Tran, D. L. T. (2025). Tourism and contribution to employment: Global evidence. Journal of Economics and Development, 27(1), 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q. H. (2021). Impact of investment in tourism infrastructure development on attracting international visitors: A nonlinear panel ARDL approach using Vietnam’s data. Economies, 9(3), 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonthapot, S. (2018). Causality between capital investment in the tourism sector and tourist arrivals in ASEAN. Journal of Advanced Research in Law and Economics, 8(8), 2504–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurjanana, N., Darma, D. C., Suparjo, S., Kustiawan, A., & Wasono, W. (2025). Two-way causality between economic growth and environmental quality: Scale in the new capital of Indonesia. Sustainability, 17(4), 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, J. V., Rachinger, H., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2021). Does tourism promote economic growth? A fractionally integrated heterogeneous panel data analysis. Tourism Economics, 28(5), 1355–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philander, K., & Roe, S. J. (2013). The impact of wage rate growth on tourism competitiveness. Tourism Economics, 19(4), 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piboonrungroj, P., Wannapan, S., & Chaiboonsri, C. (2023). The impact of gastronomic tourism on Thailand economy: Under the situation of COVID-19 pandemic. SAGE Open, 13(1), 21582440231154803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilis, W., Kabus, D., & Miciuła, I. (2022). Food services in the tourism industry in terms of customer service management: The case of Poland. Sustainability, 14(11), 6510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybyła, K., Kachniarz, M., Kulczyk-Dynowska, A., & Ramsey, D. (2019). The impact of changes in administrative status on the tourist functions of cities: A case study from Poland. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 32(1), 578–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmatullah, M. Z. A. A., & Marseto, M. (2024). Analysis of inflation, regional gross domestic product and minimum wage on employment absorption in East Nusa Tenggara Province. Journal of Business Management and Economic Development, 2(3), 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, A., Nurmawati, E., & Sugiyarto, T. (2024). Nowcasting hotel room occupancy rate using google trends index and online traveler reviews given lag effect with machine learning (case research: East Kalimantan Province). Scientific Journal of Informatics, 11(2), 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, R., Rohmah, M., Ulfah, Y., Juwita, R., Noor, M. F., & Arifin, Z. (2023). Becoming a viewer again? Optimizing educational tour at IKN Nusantara to encourage community enthusiasm. Jurnal Perspektif Pembiayaan dan Pembangunan Daerah, 11(2), 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmayani, D., Oktavilia, S., Suseno, D., Isnaini, E., & Supriyadi, A. (2022). Tourism development and economic growth: An empirical investigation for Indonesia. Economics Development Analysis Journal, 11(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raifu, I. A., & Afolabi, J. A. (2024). Does rising inflation affect the tourism industry? Evidence from Nigeria. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, H., Maqbool, S., & Tarique, M. (2021). The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: A panel cointegration analysis. Future Business Journal, 7(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivandi, S., & Pramono, S. (2024). IKN: Economic opportunity or threat? a comprehensive public policy analysis on the economic and social impacts of Indonesia’s capital city relocation. Jurnal Public Policy, 10(2), 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S., Farhang, A., Mohammadpour, A., & Hajibolnd, M. (2024). The asymmetric effects of political risk, exchange rate and inflation rate on the development of tourism industry in Iran. The Economic Research, 24(2), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Sadekin, M. N. (2025). Relationship among tourism, FDI, and economic growth in Bangladesh. Discover Sustainability, 6(1), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samila, P., Sam, I., & Safelia, N. (2025). The influence of hotel tax, restaurant tax and entertainment tax on regional original revenue with economic growth as a moderating variabel. Jurnal Cakrawala Akuntansi, 15(1), 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkhanov, T., & Baghirov, A. (2023). Impact of tourism revenues and inflation on economic growth: An empirical study on GUAM countries. Multidisciplinary Reviews, 7(3), 2024047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez López, F. (2019). Unemployment and growth in the tourism sector in Mexico: Revisiting the growth-rate version of Okun’s law. Economies, 7(3), 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez López, F. (2024). Tourism and economic misery: Theory and empirical evidence from Mexico. Economies, 12(4), 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., Perdue, R. R., & Nicolau, J. L. (2022). The effect of lodging taxes on the performance of US hotels. Journal of Travel Research, 61(1), 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J., & Mitra, S. K. (2020). Asymmetric relationship between tourist arrivals and employment. Tourism Economics, 27(5), 952–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L. (2017). Factors determining the success or failure of a tourism tax: A theoretical model. Tourism Review, 72(3), 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H., Yu, Q., Liu, K., Wang, A., & Zha, J. (2022). Understanding wage differences across tourism-characteristic sectors: Insights from an extended input-output analysis. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 51, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simorangkir, C. O., Ramadhan, G., Sukran, M. A., & Manalu, T. (2024). Tourism development impact on economic growth and poverty alleviation in West Java. Jurnal Kepariwisataan Indonesia: Jurnal Penelitian Dan Pengembangan Kepariwisataan Indonesia, 18(2), 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokhanvar, A., & Jenkins, G. P. (2022). Impact of foreign direct investment and international tourism on long-run economic growth of Estonia. Journal of Economic Studies, 49(2), 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarin, S. A., Lasisi, T. T., Hossain, M. E., & Bekun, F. V. (2023). Diversification in the tourism sector and economic growth in Australia: A disaggregated analysis. International Journal of Tourism Research, 25(6), 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmana, E., & Azizah, A. (2024). New capital city of Indonesia, an opportunity or threat for ecotourism resilience in East Borneo. Journal of Disaster Research, 19(1), 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-Y., Li, M., Lenzen, M., Malik, A., & Pomponi, F. (2022). Tourism, job vulnerability and income inequality during the COVID-19 pandemic: A global perspective. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 3(1), 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z., Liu, L., Pan, R., Wang, Y., & Zhang, B. (2025). Tourism and economic growth: The role of institutional quality. International Review of Economics & Finance, 98, 103913. [Google Scholar]

- Swenson, C. (2021). Empirical evidence on the economic impacts of hotel taxes. Economic Development Quarterly, 36(1), 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syaban, A. S. N., & Appiah-Opoku, S. (2023). Building Indonesia’s new capital city: An in-depth analysis of prospects and challenges from current capital city of Jakarta to Kalimantan. Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 11(1), 2276415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syaban, A. S. N., & Appiah-Opoku, S. (2024). Unveiling the complexities of land use transition in indonesia’s new capital city IKN Nusantara: A multidimensional conflict analysis. Land, 13(5), 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uula, M. M., Maulida, S., & Rusydiana, A. S. (2024). Tourism sector development and economic growth in OIC countries. Halal Tourism and Pilgrimage, 3(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vašaničová, P., & Bartók, K. (2024). Exploring the nexus between employment and economic contribution: A study of the travel and tourism industry in the context of COVID-19. Economies, 12(6), 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, D. B., Maiti, M., & Petrović, M. D. (2023). Tourism employment and economic growth: Dynamic panel threshold analysis. Mathematics, 11(5), 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, A., Koens, K., & Milano, C. (2022). Overtourism and employment outcomes for the tourism worker: Impacts to labour markets. Tourism Review, 77(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Tziamalis, A. (2023). International tourism and income inequality: The role of economic and financial development. Tourism Economics, 29(7), 1836–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A., Kebete, Y., & Li, Y. (2021). Culinary tourism as a driver of regional economic development and socio-cultural revitalization: Evidence from Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100482. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, N., Sun, B., Jiang, L., & Cui, H. (2022). Spatial effects of climate change on tourism development in china: An analysis of tourism value chains. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 952395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, M., Muthalib, A. A., Rostin, R., & Rahim, M. (2020). Influence of the number of tourism visits, and hotel occupancy on tourism sector revenue and economic growth in Indonesia. SSRG International Journal of Economics and Management Studies, 7(8), 196–200. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z., Lv, P., & Sun, S. (2025). The impact of new infrastructure investment on the international tourism industry: Evidence from provincial-level panel data in China. Sustainability, 17(6), 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılancı, V., & Kırca, M. (2024). Testing the relationship between employment and tourism: A fresh evidence from the ARDL bounds test with sharp and smooth breaks. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(1), 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamfir, A., & Corbos, R.-A. (2015). Towards sustainable tourism development in urban areas: Case study on Bucharest as tourist destination. Sustainability, 7(9), 12709–12722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Yang, D., Zhao, X., & Lei, M. (2023). Tourism industry and employment generation in emerging seven economies: Evidence from novel panel methods. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 36(3), 2206471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfikri, A., Ishak, R. P., & Judijanto, L. (2023). Evaluation of the impact of IKN development on increasing tourism sector competitiveness, increasing tourist income, and increasing the number of tourism visits: A case study on tourist destinations in East Kalimantan. West Science Journal Economic and Entrepreneurship, 1(3), 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Data | Conceptual Definition | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labor absorption | Tingkat Partisipasi Angkatan Kerja/Labor Force Participation Rate (TPAK) in the tourism sector | Percentage of the labor force in the tourism sector, which encompasses accommodation, food and beverage services, tourist transportation, travel agencies, and cultural and recreational activities, as compared to the total working-age population (aged 15 years and older) | Percentage (%) |

| Tourist visits | Number of tourist visits | Average number of domestic and foreign tourists entering and visiting destinations and recreations | Tourists (person) |

| Wages | Upah Minimum Kabupaten/District Minimum Wage (UMK) | The minimum wage standard officially set by the district government that must be paid by employers to workers or laborers as the lowest monthly wage | Indonesian Rupiah (IDR) |

| Occupancy rates | Number of hotel (non-star) and lodging guests | The number of tourists who fill and rent rooms from either hotels (non-star) or lodgings, calculated per year | Tourists (person |

| Room rates | Average stay rate per room | Average rental rate per year set by (non-star) hotels and lodgings | Indonesian Rupiah (IDR) |

| Food and beverage facilities | Restaurants, cafes, and eateries | Number of restaurants, cafes, and eateries | Business unit |

| Inflation | Inflation rate | Percentage of the average increase in the prices of goods and services in the tourism sector per year, based on the CPI of the nearest region (in this case, Balikpapan City) as a reference, representation, and proxy | Percentage (%) |

| Hotel and lodging taxes | Hotel and lodging tax revenue | Realization of local tax revenue from hotels (non-star) and lodgings | Indonesian Rupiah (IDR) |

| Restaurant and eating-house taxes | Restaurant and eatery receipts | Realization of local tax revenue from restaurants and eateries | Indonesian Rupiah (IDR) |

| Investment | Investment credit in the tourism sector | Investment loans disbursed by public and private banks to the tourism sector | Indonesian Rupiah (IDR million) |

| Economic growth | GRDP growth in the tourism sector | Economic growth at constant prices in the tourism sector | Percentage (%) |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labor absorption | 14.14 | 20.18 | 17.62 | 0.49 |

| Tourist visits | 18,692 | 236,953 | 76,688.17 | 22,001.99 |

| Wages | 1,903,262 | 3,715,817 | 2,885,245.75 | 175,413.76 |

| Occupancy rates | 8083 | 52,502 | 17,739.75 | 4225.5 |

| Room rates | 225,000 | 400,000 | 293,750 | 14,798.2 |

| Food and beverage facilities | 43 | 91 | 68.33 | 4.53 |

| Inflation | 0.65 | 8.56 | 3.94 | 0.68 |

| Hotel and lodging taxes | 105,652,857 | 790,407,664 | 223,393,939.58 | 56,400,522.99 |

| Restaurant and eating-house taxes | 1,653,106,658 | 5,114,157,408 | 2,695,859,227.25 | 276,753,825.52 |

| Investment | 246,251 | 843,181 | 486,865.58 | 49,868.18 |

| Economic growth | –3.47 | 14.85 | 6.4 | 1.49 |

| Obs. | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 |

| Statistic (Sig.) | 95% CI (Lower Bound) | 95% CI (Upper Bound) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labor absorption | 0.195 * (0.200) | 16.529 | 18.706 |

| Tourist visits | 0.288 (0.007) | 28,262.122 | 125,114.211 |

| Wages | 0.201 (0.194) | 2,499,162.666 | 3,271,328.834 |

| Occupancy rates | 0.386 (0.000) | 8439.485 | 27,040.015 |

| Room rates | 0.201 (0.193) | 261,179.38 | 326,320.62 |

| Food and beverage facilities | 0.188 * (0.200) | 58.359 | 78.307 |

| Inflation | 0.219 (0.118) | 2.457 | 5.433 |

| Hotel and lodging taxes | 0.321 (0.001) | 99,257,225.466 | 347,530,653.7 |

| Restaurant and eating-house taxes | 0.243 (0.049) | 2,086,728,164.282 | 3,304,990,290.218 |

| Investment | 0.180 * (0.200) | 377,106.468 | 596,624.699 |

| Economic growth | 0.170 * (0.200) | 3.132 | 9.679 |

| Obs. | 132 | 132 | 132 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labor absorption | 1 | 0.101 (0.754) | 0.289 (0.363) | –0.010 (0.976) | 0.071 (0.825) | 0.257 (0.420) | –0.187 (0.561) | 0.062 (0.848) | 0.019 (0.954) | 0.362 (0.248) | –0.472 (0.121) |

| Tourist visits | 0.101 (0.754) | 1 | 0.695 * (0.012) | 0.970 ** (0.000) | 0.795 ** (0.002) | 0.702 * (0.011) | –0.362 (0.247) | 0.887 ** (0.000) | 0.884 ** (0.000) | 0.829 ** (0.001) | 0.318 (0.314) |

| Wages | 0.289 (0.363) | 0.695 * (0.012) | 1 | 0.644 * (0.024) | 0.873 ** (0.000) | 0.951 ** (0.000) | –0.801 ** (0.002) | 0.649 * (0.022) | 0.807 ** (0.002) | 0.872 ** (0.000) | –0.197 (0.539) |

| Occupancy rates | –0.010 (0.976) | 0.970 ** (0.000) | 0.644 * (0.024) | 1 | 0.789 ** (0.002) | 0.643 * (0.024) | –0.259 (0.415) | 0.823 ** (0.001) | 0.845 ** (0.001) | 0.743 ** (0.006) | 0.320 (0.310) |

| Room rates | 0.071 (0.825) | 0.795 ** (0.002) | 0.873 ** (0.000) | 0.789 ** (0.002) | 1 | 0.884 ** (0.000) | –0.505 (0.094) | 0.838 ** (0.001) | 0.938 ** (0.000) | 0.882 ** (0.000) | 0.208 (0.516) |

| Food and beverage facilities | 0.257 (0.420) | 0.702 * (0.011) | 0.951 ** (0.000) | 0.643 * (0.024) | 0.884 ** (0.000) | 1 | –0.737 ** (0.006) | 0.659 * (0.020) | 0.803 ** (0.002) | 0.894 ** (0.000) | –0.002 (0.946) |

| Inflation | –0.187 (0.561) | –0.362 (0.247) | –0.801 ** (0.002) | –0.259 (0.415) | –0.505 (0.094) | –0.737 ** (0.006) | 1 | –0.309 (0.328) | –0.483 (0.112) | –0.571 (0.053) | 0.394 (0.205) |

| Hotel and lodging taxes | 0.062 (0.848) | 0.887 ** (0.000) | 0.649 * 0(0.022) | 0.823 ** (0.001) | 0.838 ** (0.001) | 0.659 * (0.020) | –0.309 (0.328) | 1 | 0.941 ** (0.000) | 0.834 ** (0.001) | 0.429 (0.164) |

| Restaurant and eating-house taxes | 0.0019 (0.954) | 0.884 ** (0.000) | 0.807 ** (0.002) | 0.845 ** (0.001) | 0.938 ** (0.000) | 0.803 ** (0.002) | –0.483 (0.112) | 0.941 ** (0.000) | 1 | 0.885 ** (0.000) | 0.339 (0.281) |

| Investment | 0.362 (0.248) | 0.829 ** (0.001) | 0.872 ** (0.000) | 0.743 ** (0.006) | 0.882 ** (0.000) | 0.894 ** (0.000) | –0.571 (0.053) | 0.834 ** (0.001) | 0.885 ** (0.000) | 1 | 0.038 (0.906) |

| Economic growth | –0.472 (0.121) | 0.318 (0.314) | –0.197 (0.539) | 0.320 (0.310) | 0.208 (0.516) | –0.022 (0.946) | 0.394 (0.205) | 0.429 (0.164) | 0.339 (0.281) | 0.038 (0.906) | 1 |

| Obs. | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.003 (0.205) | –2.669 (0.228) | 2.809 (0.218) |

| Labor absorption | 14.092 * (0.045) | –13.430 * (0.047) | |

| Tourist visits | 14.092 * (0.045) | 30.277 * (0.021) | |

| Wages | –9.847 (0.064) | 17.268 * (0.037) | –26.452 * (0.024) |

| Occupancy rates | –14.527 * (0.044) | 139.842 ** (0.005) | –29.716 * (0.021) |

| Room rates | 10.790 (0.059) | –28.866 * (0.022) | 21.269 * (0.030) |

| Food and beverage facilities | 11.029 (0.058) | –16.156 * (0.039) | 23.815 * (0.027) |

| Inflation | 14.944 * (0.043) | –15.331 * (0.041) | 14.195 * (0.045) |

| Hotel and lodging taxes | –5.455 (0.115) | 6.132 (0.103) | –5.938 (0.106) |

| Restaurant and eating-house taxes | 3.375 (0.183) | –3.483 (0.178) | 3.691 (0.168) |

| Investment | –11.045 (0.057) | 30.277 * (0.021) | –23.508 * (0.027) |

| Economic growth | –13.430 * (0.047) | 25.582 * (0.025) | |

| F (sig.) | 57.579 * (0.021) | 58.884 ** (0.000) | 43.788 * (0.023) |

| R2 | 0.998 | 1 | 0.927 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.981 | 0.999 | 0.911 |

| Std. error of the estimate | 0.237 | 0.232 | 0.289 |

| Obs. | 132 | 132 | 132 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 4.278 (1.424) | –11,848.671 (4325.504) | 2.824 (1.006) |

| Labor absorption | 0.061 (193.577) | –0.221 (0.049) | |

| Tourist visits | 16.224 (0.000) | 3.595 (0.000) | |

| Wages | –7.240 (0.000) | 0.447 (0.003) | –1.608 (0.000) |

| Occupancy rates | –12.918 (0.000) | 0.796 (0.030) | –2.862 (0.000) |

| Room rates | 6.600 (0.000) | –0.407 (0.021) | 1.464 (0.000) |

| Food and beverage facilities | 4.535 (0.045) | –0.279 (83.972) | 1.006 (0.014) |

| Inflation | 1.964 (0.096) | –0.121 (256.377) | 0.434 (0.067) |

| Hotel and lodging taxes | –1.589 (0.000) | 0.098 (0.000) | –0.352 (0.000) |

| Restaurant and eating-house taxes | 1.259 (0.000) | –0.080 (0.000) | 0.288 (0.000) |

| Investment | –5.533 (0.000) | 0.341 (0.006) | –1.228 (0.000) |

| Economic growth | –4.509 (0.112) | 0.278 (135.763) | |

| Obs. | 132 | 132 | 132 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Surgawati, I.; Darma, S.; Putra, A.M.; Sarifudin, S.; Ariani, M.; Ashari, I.; Darma, D.C. Dissecting the Economics of Tourism and Its Influencing Variables—Facts on the National Capital City (IKN). Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030125

Surgawati I, Darma S, Putra AM, Sarifudin S, Ariani M, Ashari I, Darma DC. Dissecting the Economics of Tourism and Its Influencing Variables—Facts on the National Capital City (IKN). Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(3):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030125

Chicago/Turabian StyleSurgawati, Iis, Surya Darma, Agus Muriawan Putra, Sarifudin Sarifudin, Misna Ariani, Ihsan Ashari, and Dio Caisar Darma. 2025. "Dissecting the Economics of Tourism and Its Influencing Variables—Facts on the National Capital City (IKN)" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 3: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030125

APA StyleSurgawati, I., Darma, S., Putra, A. M., Sarifudin, S., Ariani, M., Ashari, I., & Darma, D. C. (2025). Dissecting the Economics of Tourism and Its Influencing Variables—Facts on the National Capital City (IKN). Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030125