1. Introduction

Tourism has increasingly emerged as one of the industries that contributes most significantly to the global economy, displaying notable growth and continuous development. According to data from the World Travel & Tourism Council (

WTTC, 2022), in 2019, the tourism sector accounted for 10.4% of the global GDP. Before the 2019–2021 pandemic crisis, this sector was responsible for one in every four new jobs created worldwide (

WTTC, 2022). Nevertheless, the industry has faced multiple challenges, particularly due to its high competitiveness and the impact of the recent pandemic. Open innovation has become especially relevant within this sector in the current context (

Carvalho, 2018), especially considering the need for co-creative responses, stakeholder integration, and digital transformation in post-crisis recovery (

Shin, 2023;

Szromek et al., 2023).

Open innovation is commonly defined as a model aimed at enhancing business performance by integrating internal and external ideas and internal and external paths into the market, all of which may contribute to organizational development (

Chesbrough, 2003). It is therefore closely associated with exchanging knowledge and technology with external entities, including universities, competitors, individuals, and suppliers (

Artič, 2013).

According to

Chesbrough (

2003), a distinction must be made between open and closed innovation. Closed innovation refers to organizations developing, producing, and commercializing new products and services exclusively by relying on internal resources and technologies. In contrast, open innovation involves both inbound and outbound flows of knowledge, accelerating internal innovation processes and, consequently, the expansion of markets for the external use of innovation (

da Inês et al., 2021). Therefore, while closed innovation involves companies maintaining their innovation efforts entirely in house, based on the premise that innovation can be developed solely internally, open innovation advocates exchanging ideas and experiences beyond organizational boundaries to enrich the process.

Chesbrough (

2003) further classifies open innovation into three main types: (i) inbound (outside–in), which involves sourcing and integrating external ideas and knowledge; (ii) outbound (inside–out), in which internal ideas are shared externally to create additional value; and (iii) coupled processes that combine both dimensions through co-creation with partners. These typologies are essential in understanding how tourism firms interact within innovation ecosystems.

An examination of the existing literature on open innovation reveals that most studies have focused on developing new physical products, particularly within the manufacturing sector, with considerably less attention given to service-based industries such as tourism (

Aas, 2016). Although some foundational efforts have explored the intersection between open innovation and tourism (

Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2019a), only more recently has a body of empirical research begun to emerge that explicitly addresses this relationship (

Cardoso et al., 2024;

Rehman et al., 2024;

Mota et al., 2024). Since the existing research on open innovation has concentrated on product development, a key research question arises: Does open innovation provide advantages or benefits for the tourism industry?

This study seeks to contribute to the academic literature by analyzing evidence on using open innovation in the tourism industry. Specifically, it aims to explore the current state of research in this field, identify the benefits of applying open innovation in tourism, and outline its implications for future research. This includes examining strategic drivers, such as stakeholder co-creation and green innovation (

Tuan, 2025;

Luu, 2025), and operational dimensions, such as employee empowerment and digital responsiveness (

Shin, 2023;

Pitakaso et al., 2025).

Reviewing previous evidence can serve as a valuable and relevant tool for identifying theoretical perspectives and establishing pathways for new research (

Snyder, 2019). A review must adhere to a clearly defined methodological framework to be rigorous. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines offer essential recommendations for developing high-quality reviews. These guidelines consist of a 27-item checklist and a flow diagram, designed to assist authors in improving the transparency and methodological quality of their reviews (

Moher et al., 2009). The present article adopts the PRISMA framework to guide its systematic selection and synthesis of 35 peer-reviewed articles retrieved from the Scopus database, marking a significant expansion in the empirical basis of prior literature reviews.

The article is structured into six distinct sections. Following the introduction,

Section 2 presents a literature review on open innovation and the tourism industry.

Section 3 outlines the adopted methodology, and

Section 4 presents the results obtained.

Section 5 provides the discussion. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the study by presenting its practical implications, theoretical contributions, limitations, and avenues for future research.

2. Open Innovation and the Tourism Industry

Open innovation is a concept rooted in innovative management and is regarded as a practical model based on collaboration between individuals and organizations within and beyond the firm’s boundaries (

Yun et al., 2016). Open innovation is evolving rapidly within high-tech industries and other sectors, as it facilitates technological advancement, market expansion, increased revenue generation, and improves the research and development of new products (

Qiu et al., 2021).

Given the growing importance of the service sector in the economies of developed countries, scholarly interest in analyzing innovation within this domain has significantly increased (

Chen et al., 2016). In the tourism context, innovation can be regarded as a continuous challenge, owing to the imperative that firms adapt to the evolving profiles of tourists, who are increasingly demanding and better informed (

Stamboulis & Skayannis, 2003). Tourism-related businesses must continually adjust to these shifts (

Voorberg et al., 2015). Consequently, the industry must deliver unique and innovative experiences that foster stronger market engagement and sustain competitive positioning (

Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2020;

Biconne et al., 2023).

Innovation is a key factor in developing competitive advantage, particularly for firms operating in the fast-evolving tourism sector (

Martínez-Pérez et al., 2019). It enables businesses to quickly respond to uncertain environmental conditions and maintain or enhance their competitiveness (

Gkypali et al., 2017). Typically, firms pursue open innovation to generate creative and novel products (

Lopes & de Carvalho, 2018).

Hoyer et al. (

2010) identified several benefits of open innovation, including reduced costs for new service development, accelerated innovation processes, enhanced customer-oriented corporate image, and greater responsiveness to customer needs. However, to adopt open innovation, firms operating in the tourism industry must make strategic choices that leverage external knowledge, skills, capabilities, and internal resources and competencies (

Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006;

Mota et al., 2024). Acquiring external knowledge through customer involvement becomes essential to innovation, with the foremost priority in service innovation being understanding customers and their needs (

Heinonen & Strandvik, 2021).

The tourism industry generally requires open innovation to enhance its offerings and differentiate between competing destinations. Cities, for instance, must develop new narratives to sustain their success and positioning, and to that end, fostering a culture of open innovation is essential (

Carrasco-Santos et al., 2021;

Rehman et al., 2024).

Open innovation has increasingly demonstrated that, when applied to the tourism sector, it can lead to greater customer satisfaction, enhanced brand recognition, more effective exploitation of opportunities, and the development of new products or services (

Lim et al., 2021;

Cardoso et al., 2024). Consequently, open innovation may serve as a means of expanding effective solutions that protect not only individual businesses, but the entire tourism sector from threats (

Szromek & Polok, 2022;

Szromek et al., 2023).

According to

Cruz-Ruiz et al. (

2022), collaborative innovation processes contribute to more efficient resource utilization and generate cost-reduction capabilities over the long term by minimizing expenditures and conserving resources. Through open innovation, sustainable and economically viable services that consider the interests of all stakeholders can be more easily designed, making the impact of open innovation processes on tourism-based business models increasingly important (

Jutidharabongse et al., 2024).

Moreover, advances in information technology have enabled customers to effortlessly share their experiences via online reviews, positioning them as valuable open sources of service innovation knowledge (

Lee et al., 2019). These customers provide novel ideas for service improvement (

Lusch & Nambisan, 2015), transforming digital platforms into an important medium for open innovation (

Elia et al., 2020). The strategic use of external resources provides hotels with a platform to access diverse ideas, thereby encouraging staff to integrate these ideas into unconventional combinations that result in new services or products. This aligns with the principle of “using external ideas as well as internal ones” inherent in the open innovation paradigm (

Chesbrough et al., 2008;

Shin, 2023).

Liu (

2017) indicates that exploratory organizational learning fosters employees’ innovative behaviors. Employees empowered with knowledge, support, resources, and opportunities are likelier to exhibit creative behaviors (

Akgunduz et al., 2018). Moreover, collaboration, adequate resource support, and managerial involvement significantly enhance employee confidence, motivate them to perform better (

Baker & Kim, 2020), and cultivate a desire to innovate and transform, reinforcing trust in innovative conduct (

Tsai et al., 2015;

Tuan, 2025).

According to

Khan et al. (

2021), the hotel industry must shift from traditional business models to innovative strategies to build customer trust and offer safe, reliable experiences. Although the transition to e-business and e-commerce was already underway, the recent pandemic crisis has significantly accelerated the adoption and development of open innovation within the industry (

Pitakaso et al., 2025). Although the tourism industry holds significant potential to engage in open innovation, particularly by involving customers in service delivery and development processes, this area remains relatively underexplored (

Cui & Wu, 2016;

Mota et al., 2024).

Moreover, several conceptual strands within open innovation remain underexplored in tourism. For example, social open innovation, which emphasizes inclusive, community-based approaches, has been referenced in studies involving co-creation with residents and tourists (

Carrasco-Santos et al., 2021;

Cruz-Ruiz et al., 2022). The idea of an Open Innovation Culture, that is, an organizational mindset and values fostering openness, has been associated with empowerment and collaborative learning environments (

Gusakov et al., 2020;

Shin & Perdue, 2022). Other studies touch upon the complexity and limits of open innovation, particularly regarding the challenges of managing trust, power asymmetries, and stakeholder expectations (

Rehman et al., 2024;

Jutidharabongse et al., 2024). Finally, research on open innovation in SMEs highlights how small tourism enterprises engage in participatory innovation despite limited resources (

Biconne et al., 2023;

Mota et al., 2024).

3. Methods

To analyze the evolution of the topic, this study adopted a systematic literature review (SLR) methodology to identify, classify, and synthesize the existing body of knowledge. This approach allows for the precise retrieval of academic publications and enables the synthesis of recent research findings (

Grant & Booth, 2009).

The adopted review methodology followed the process proposed by

Denyer and Tranfield (

2009), which consists of identifying existing studies on the subject, selecting and assessing their contributions, analyzing and synthesizing the findings, and disseminating the resulting evidence clearly and in a structured format, allowing for well-grounded conclusions and suggestions for future research directions.

Aligned with the objective of this study, this study aims to address the following research questions:

What are the main thematic areas and methodological characteristics of empirical studies on open innovation in the tourism sector?

How does empirical research conceptualize and demonstrate the benefits and strategic outcomes of open innovation in tourism?

Based on the answers to the research questions, implications for future research are proposed.

The Scopus database was selected to conduct the analysis, as it is recognized as one of the largest and most comprehensive academic databases (

Baas et al., 2020). The study considered all articles indexed in Scopus up to 2025. To identify relevant articles, the following search string was applied: “Open innovation” AND “tourism industry” OR “tourism” OR “hospitality” OR “hotels” OR “leisure”.

This search initially yielded 78 publications, published between 2009 and 2025. The year 2009 was selected as the starting point because it corresponds to the earliest publication applying the concept of open innovation explicitly to the tourism sector in the peer-reviewed literature indexed in Scopus.

Subsequently, only peer-reviewed journal articles in English, belonging to the subject areas of “Business, Management and Accounting” and “Economics, Econometrics and Finance”, were selected. Metadata such as authors, title, abstract, year, keywords, and source were downloaded and analyzed. Articles that did not align with the objectives and scope of this study were excluded. The Scopus database was selected for its extensive coverage of the high-quality, peer-reviewed literature in the fields of management, innovation, and tourism. The search was restricted to the subject areas of “Business, Management and Accounting” and “Economics, Econometrics and Finance” to ensure thematic relevance and conceptual rigor, given the study’s focus on innovation processes and strategic applications within tourism organizations.

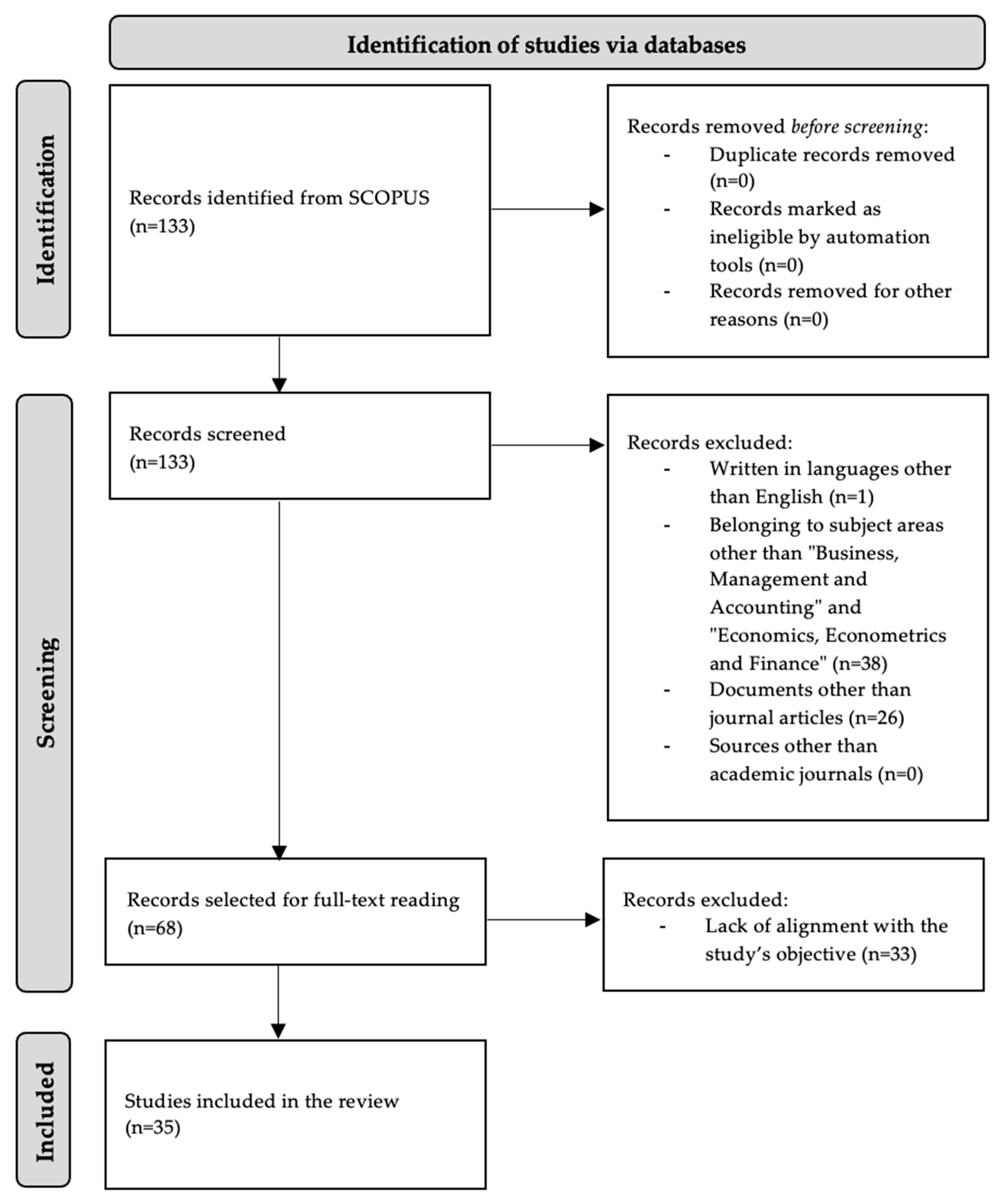

Following the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 98 articles were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 35 articles (see

Appendix A) considered relevant and appropriate for inclusion in the review.

A schematic flow diagram outlining each review process step is presented in

Figure 1, following the PRISMA guidelines.

The eligibility criteria were restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles published in English that presented primary empirical findings directly related to open innovation and tourism. Records written in other languages, unrelated to the disciplines of “Business, Management and Accounting” or “Economics, Econometrics and Finance,” as well as documents that were not journal articles (e.g., conference papers, book chapters, or theoretical works), were excluded.

A total of 78 records were initially identified through the SCOPUS database. No duplicates or irrelevant entries were removed before screening. Both authors independently screened titles and abstracts using a double-blind process. Of the 133 records screened, 65 were excluded based on language, subject area, or document type. The process resulted in 68 records for full-text review. During this phase, 33 articles were excluded due to a lack of alignment with the research objective. As a result, 35 studies were included in the final review.

The authors conducted data extraction independently, using cross-validation procedures to ensure consistency and accuracy. The final dataset formed the basis for the thematic synthesis.

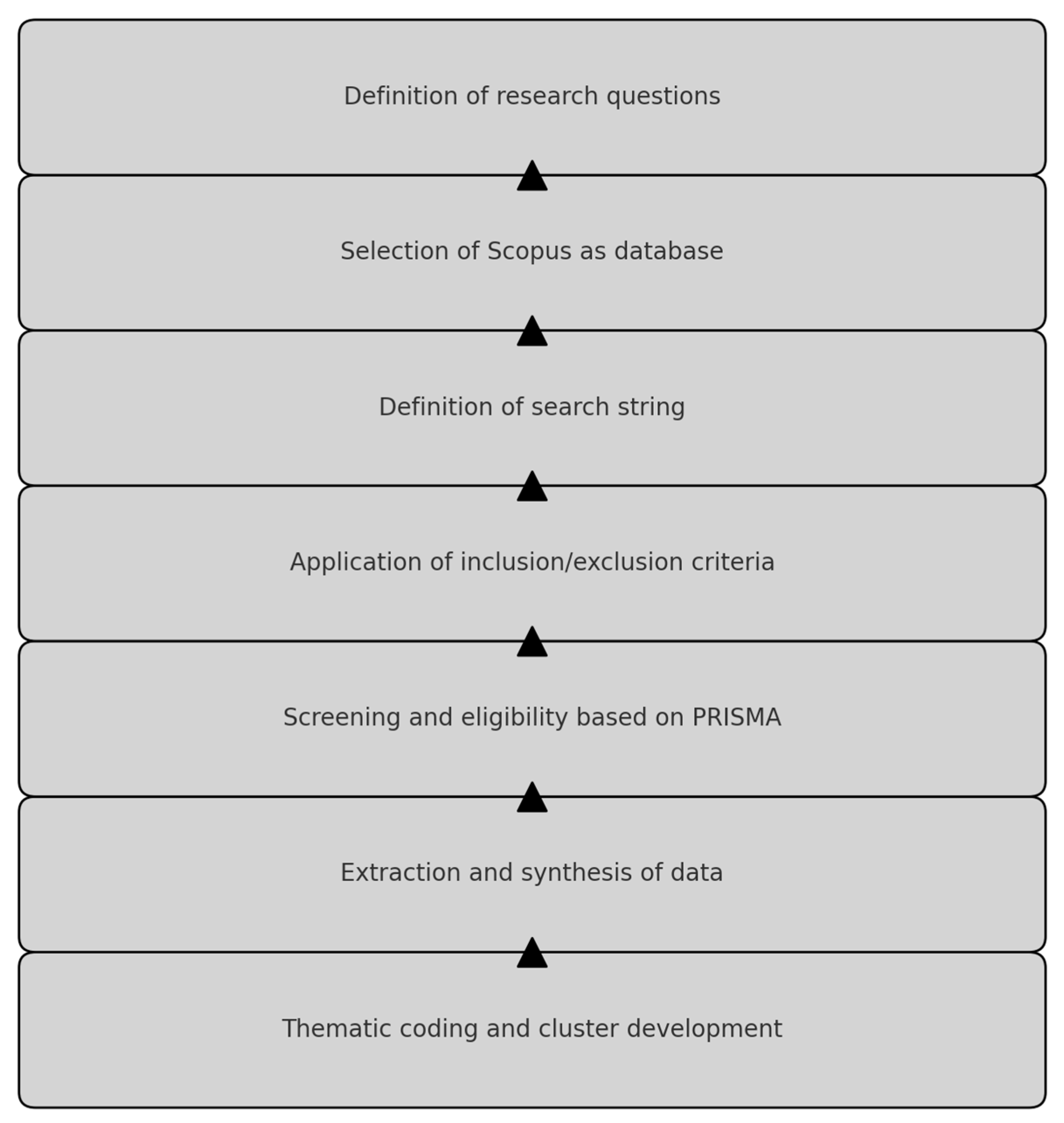

To complement the methodological transparency of the review process,

Figure 2 presents a visual summary of the sequential steps adopted in the systematic review. This figure outlines the entire protocol, beginning with the formulation of the research questions and the selection of the Scopus database, followed by the construction of the search string and the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. The screening and eligibility procedures were conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. Subsequently, the selected articles underwent data extraction, cross-validation, and thematic synthesis. The final stage involved the coding of data into thematic clusters, allowing for a structured and coherent analysis of the literature. This stepwise framework ensures replicability and enhances the methodological rigor of the study.

4. Descriptive Results

Studies that explore the intersection between open innovation and the tourism industry have shown a notable increase in academic attention in recent years. Specifically, 2019 stands out as a pivotal point, recording six publications on the subject, accounting for 17.14% of the total number of studies included in this systematic review (see

Table 1). This sharp increase may reflect the growing recognition of the potential benefits that open innovation can offer tourism-related enterprises and destinations, particularly concerning competitiveness, adaptability, and value co-creation.

Furthermore, a significant concentration of academic output has been observed between 2019 and 2022, during which 18 out of 35 studies were produced, representing 51.43% of the selected publications. This temporal distribution suggests that the academic community has increasingly acknowledged the relevance of integrating open innovation models into the dynamics of the tourism industry, especially considering some global challenges, such as digital transformation, sustainability demands, and the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition, the growing relevance of the topic in the post-pandemic context is evidenced by the steady number of publications from 2023 (two articles) and 2024 (five articles), as well as by the emergence of early contributions in 2025 (three articles)—a particularly notable figure considering that the year is still ongoing. These findings indicate an upward trend in the academic discourse on the topic and a progressive shift in the research focus, from traditional innovation approaches towards more collaborative, open, and cross-sectoral strategies in tourism innovation management.

As presented in

Table 2, the 35 articles selected for this systematic review were published in 19 peer-reviewed academic journals, reflecting the thematic diversity and growing scholarly interest in the intersection between open innovation and the tourism sector. Among these journals, three stand out for their recurring engagement with the topic: the

Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, with ten published articles, and both the

International Journal of Hospitality Management and the

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, with three articles each. These three journals alone account for 45.71% of all reviewed publications, underscoring their prominent role in advancing the discourse on innovation in tourism and hospitality contexts.

The remaining articles are distributed across various specialized and multidisciplinary journals, suggesting a broad academic reach and an openness to cross-sectoral and cross-disciplinary perspectives. This distribution illustrates how open innovation in tourism is not confined to a single academic outlet but is rather integrated into diverse editorial domains that support research in business, management, innovation, and service industries. The dispersion also reflects the flexibility of the open innovation paradigm and its applicability across different conceptual and empirical approaches within the tourism literature.

The 35 articles selected involve a total of 100 co-authors, reflecting a moderate level of scholarly collaboration in the field of open innovation applied to the tourism industry. The research community on the topic seems to be expanding, with contributions originating from various institutional and national contexts.

In terms of academic impact, the selected articles have collectively received 2010 global citations, as indexed by Scopus. This review considers two citation metrics: Total Global Citations (TGCs) and Total Local Citations (TLCs). The TGCs refers to the total number of times each article has been cited globally, according to Scopus, and serves as an indicator of each publication’s overall academic visibility and reach (

Alon et al., 2018). In contrast, the TLCs specifically refers to the number of times an article has been cited within the corpus of the 35 articles included in this systematic review, measuring each article’s degree of influence or interconnection within the selected body of literature.

While the TGCs offers a broader view of external recognition, the TLCs highlights each study’s internal relevance and foundational value in shaping the current academic discourse on open innovation in the tourism context. Articles with higher TLC values may be interpreted as playing a central role in framing and advancing this emerging research domain. As detailed in

Table 3, the top ten most cited articles illustrate the academic visibility and interconnection patterns within the reviewed literature.

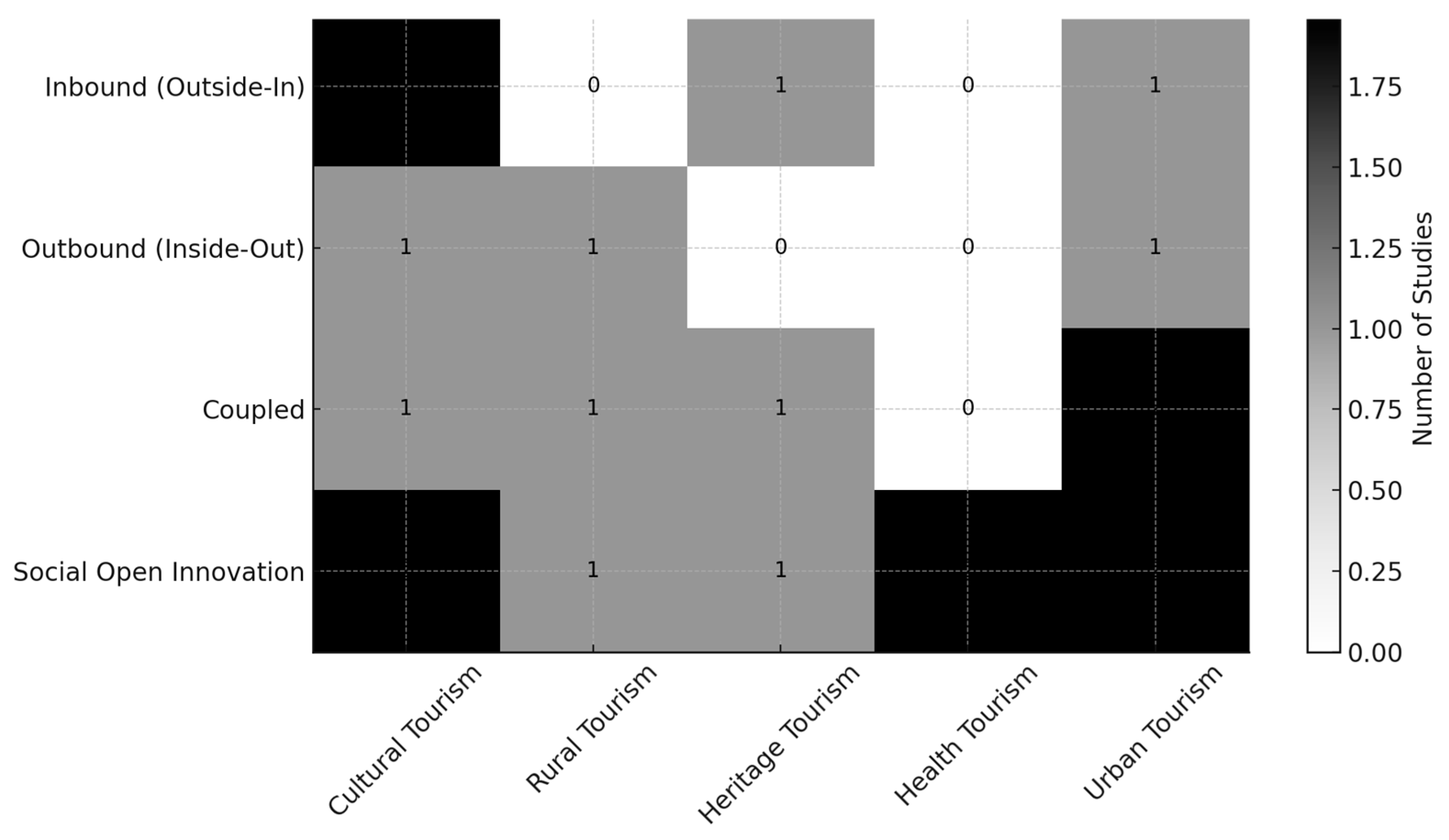

To enrich the analytical scope of the findings,

Figure 3 maps the reviewed studies according to the type of open innovation approach they adopt, namely inbound, outbound, coupled, and social open innovation, and the specific tourism segments addressed, including cultural, rural, heritage, health, and urban tourism. The matrix demonstrates that social open innovation is particularly relevant in cultural and urban tourism settings, reflecting the importance of co-creation with stakeholders and community-based approaches. Meanwhile, coupled innovation is present across diverse segments, indicating the dual flow of knowledge in more complex innovation processes. This mapping provides an integrated perspective on how open innovation strategies are applied across the multifaceted landscape of the tourism industry.

5. Discussion

The analysis highlights the increasing academic interest in the intersection between open innovation and tourism, as evidenced by

Table 1, which indicates that a significant share of the articles on this topic (over 50%) were published between 2019 and 2022, with an additional increase in contributions from 2023 to 2025 (e.g.,

Rehman et al., 2024;

Mota et al., 2024;

Tuan, 2025). Leading and successful firms operating within the tourism sector are actively reformulating their strategic approaches to enhance competitiveness by adopting open innovation practices (

Gusakov et al., 2020;

Pitakaso et al., 2025).

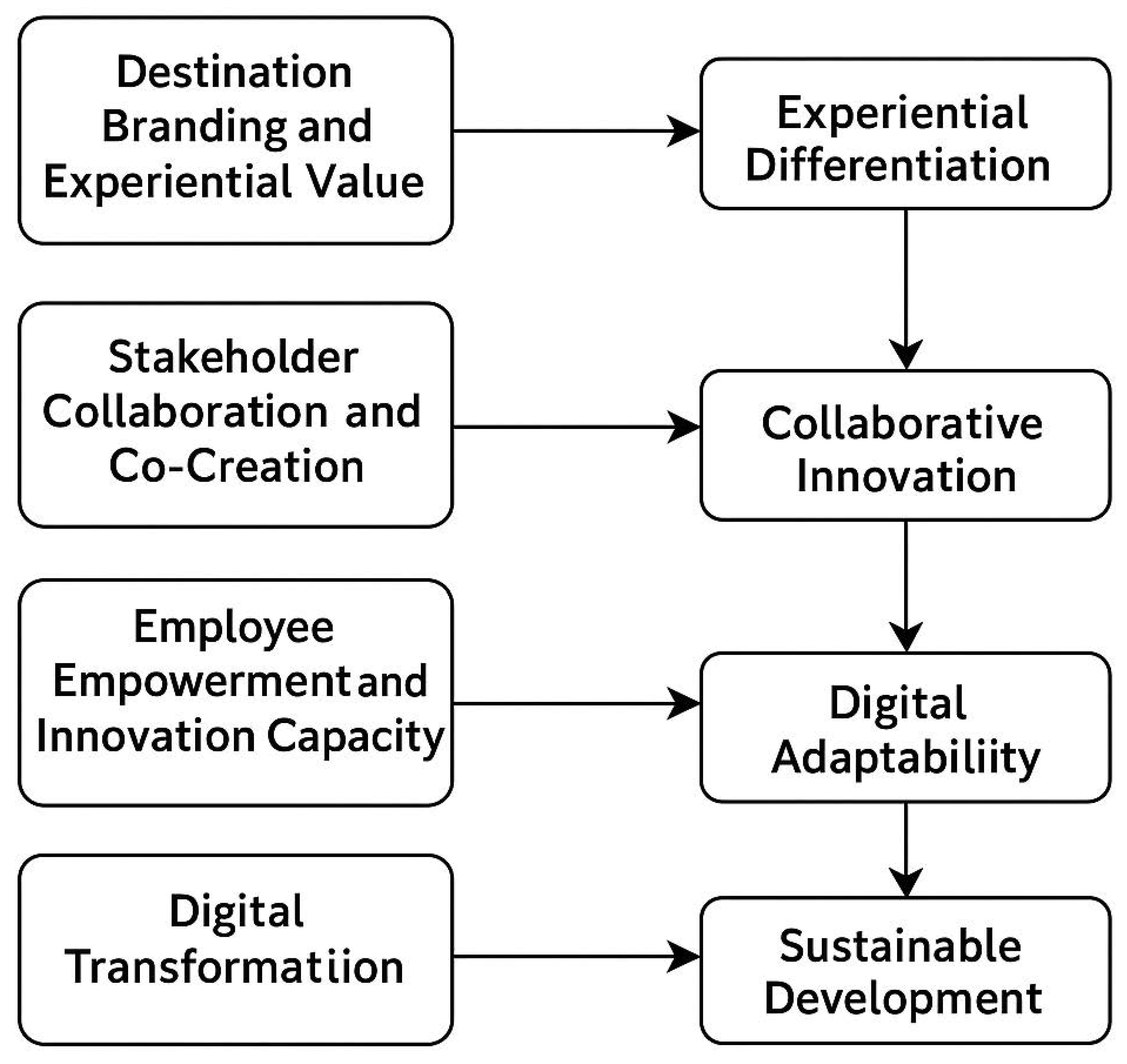

The discussion is structured around four thematic clusters, each analyzed through the lens of foundational theories of open innovation and value creation.

Chesbrough’s (

2003) open innovation model provides the overarching framework, emphasizing knowledge flows across organizational boundaries. Stakeholder theory (

Freeman & McVea, 2001;

Dredge, 2006) supports the collaborative and participatory dynamics identified in the literature. The service-dominant logic (

Vargo & Lusch, 2004,

2008) frames value as co-created among actors, while absorptive capacity theory (

Zahra & George, 2002) informs the analysis of internal learning and knowledge utilization within tourism organizations.

Open innovation is conceptualized as a process that involves opening organizational boundaries to foster stakeholder collaboration, thereby integrating external ideas and projects into internal strategic frameworks. This approach seeks to balance inbound and outbound innovation capabilities, creating new opportunities for value generation (

Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2019b).

Iglesias-Sánchez et al. (

2019a) observed that tourism-related enterprises have increasingly embraced open innovation as a strategic mechanism for achieving differentiation and competitive advantage. More recent studies confirm this strategic relevance, particularly when aligned with sustainability, data analytics, and digital transformation (

Cardoso et al., 2024;

Jutidharabongse et al., 2024;

Shin, 2023).

To better synthesize the empirical evidence from the selected literature, the discussion is structured around four core thematic dimensions that emerged from the review. Each theme aggregates a cluster of studies sharing conceptual and empirical similarities. The distribution of the 35 articles across these is as follows:

5.1. Tourism Branding and Experiential Value in Open Innovation (Eight Articles)

This thematic cluster brings together eight articles that explore the role of open innovation in enhancing the strategic positioning and branding of tourism destinations and firms. One of the most compelling contributions in this domain is the study by

Carrasco-Santos et al. (

2021), which analyses the online reputation of Marbella as a tourism destination. The authors argue that open innovation strategies are decisive in establishing the city’s competitive identity, particularly through digital engagement with tourists and ranking attractions based on user-generated feedback.

Similarly,

Cruz-Ruiz et al. (

2022) underscore the importance of aligning open innovation practices with brand management strategies, highlighting that such alignment allows destinations to incorporate the voices of both residents and tourists in shaping their brand narratives. The study confirms that co-created branding strategies offer greater authenticity and differentiation in the increasingly competitive tourism market.

The work by

Díaz and Duque (

2021) strengthens this argument by drawing on a vast dataset of 165,739 hotel reviews from customers worldwide. Their econometric analysis shows that open innovation practices focused on customer satisfaction significantly increase the likelihood of customer recommendations, demonstrating a direct link between open innovation and brand loyalty.

Naramski et al. (

2022) contribute a complementary perspective through their case study of a former industrial site transformed into a heritage tourism destination. Their research illustrates how open innovation facilitates the reinterpretation and revitalization of place-based assets, reinforcing territorial branding and diversifying tourism offerings.

Biconne et al. (

2023) extend this inquiry by examining open innovation in micro-tourism firms in the Italian Alps. Their findings reveal that even small-scale actors can leverage participatory innovation to reframe the identity of less prominent destinations, primarily through collaboration with local communities and visitors.

Furthermore, the study by

Mengual-Recuerda et al. (

2021) explores the emotional responses of restaurant customers to haute cuisine, drawing attention to how culinary experiences can be enhanced through creative, open innovation-based approaches. This experiential branding dimension supports the idea that destination identity is increasingly linked to multi-sensory and co-created value propositions.

The work of

Iglesias-Sánchez et al. (

2020) connects strategic branding to stakeholder involvement by demonstrating that communication channels must be designed to ensure that open innovation efforts are aligned with the perceptions and expectations of tourists and residents alike. Their findings reveal that authenticity, trust, and transparency are key drivers in strengthening brand positioning through collaborative innovation.

Additionally,

Szromek et al. (

2023) provide evidence from Central European cities, showing that tourism experts actively shape narratives through open knowledge exchange. This reinforces the idea that destination branding evolves from a continuous and inclusive innovation process, driven by multiple local actors and informed by territorial identity.

Collectively, these eight studies provide robust evidence that open innovation is not merely a functional mechanism for generating ideas, but a strategic resource for destination branding and differentiation. Integrating tourists and residents into innovation processes enables the construction of a shared destination identity, grounded in participatory values and real-time feedback mechanisms.

Moreover, this cluster reveals that open innovation strengthens the symbolic capital of places, as demonstrated by the emphasis on heritage (

Naramski et al., 2022), gastronomy (

Mengual-Recuerda et al., 2021), and digital reputation (

Carrasco-Santos et al., 2021). These diverse elements converge to produce holistic destination narratives that resonate with contemporary tourist preferences.

Another salient insight emerging from this cluster is the functional link between open innovation and customer lifetime value. As

Díaz and Duque (

2021) reveal, the propensity of customers to recommend a service is strongly influenced by firms’ openness to incorporating user feedback. This finding has profound implications for loyalty strategies in the tourism and hospitality sectors.

Notably, the reviewed studies also reveal that strategic branding through open innovation requires an integrated approach to stakeholder engagement, with public and private actors cooperating to build coherent branding ecosystems, especially in cities where tourism is a key economic driver (

Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2020). The combined insights of this cluster suggest that destination branding, when based on open innovation principles, is not a static communication exercise, but a dynamic process of identity development. Through co-creation, destinations evolve in alignment with changing tourist expectations, societal values, and technological possibilities.

Finally, the strategic use of open innovation in destination branding, as evidenced across the eight studies in the cluster, demonstrates the capacity of tourism organizations to transform external insights into sustainable competitive advantages, thus confirming the growing strategic importance of participatory branding practices in the digital age.

Open innovation fosters co-created branding strategies and enhances emotional engagement with tourists, resulting in stronger brand positioning and improved visitor experiences. The findings in this cluster resonate with the service-dominant logic of marketing (

Vargo & Lusch, 2004), where value emerges through ongoing interaction and co-creation between firms and consumers. Open innovation processes, such as involving tourists in content creation or brand experience development, reinforce the idea that experience is co-produced. This also aligns with

Pera et al. (

2016), who highlight co-creation as a source of differentiated experiential value in tourism.

5.2. Collaborative Innovation and Stakeholder Co-Creation in Tourism (10 Articles)

This second thematic cluster includes ten studies that explicitly examine the role of stakeholder participation, co-creation, and knowledge sharing in shaping open innovation practices within the tourism sector. A defining contribution in this area is the work by

Iglesias-Sánchez et al. (

2020), underscoring the critical function of communication channels facilitating two-way interactions between tourism providers and stakeholders. Their research highlights that open innovation depends on stakeholder trust, transparency, and aligned interests to achieve meaningful collaboration.

Mengual-Recuerda et al. (

2021) reinforce this position by investigating the emotional responses of diners to restaurant experiences, revealing how stakeholder knowledge, particularly that of customers, can be leveraged to co-create value and generate innovative service propositions. Their findings confirm that open innovation processes thrive in environments where customer feedback is systematized and embedded in product development cycles.

Lalicic (

2018) presents a compelling case study on stakeholder interaction within digital open innovation platforms. Her research demonstrates that constructive dialogue and collaborative problem-solving on these platforms significantly enhance the efficiency and legitimacy of innovation processes in tourism. It also concludes that the capacity to reach consensus among diverse actors is a key determinant of innovation success.

Deepening the theoretical foundation,

Iglesias-Sánchez et al. (

2019a) distinguishes between inbound and outbound knowledge flows in tourism innovation networks. They argue that effective stakeholder collaboration requires the creation of hybrid spaces (digital and physical) where ideas can circulate freely and be integrated into business strategies.

Nascimbeni et al. (

2017) expanded the creation of innovation spaces, proposing a model of student living labs in sustainable tourism. These labs serve as microcosms of participatory governance, illustrating how direct stakeholder involvement can facilitate learning and experimentation. The study shows that innovation is not simply a managerial function, but a socially distributed process involving multiple actors.

Another layer of insight is provided by the work of

Yeh and Ku (

2019), who examine how innovation capacity is influenced by knowledge exchange. Their research shows that when knowledge flows are facilitated through collaborative platforms, teams perform better and can align innovation outputs with organizational goals.

The findings of

Lalicic and Dickinger (

2019) complement this perspective by showing that customer ideas, collected through social media and digital tools, represent a rich source of innovation potential. Their study validates the importance of capturing user insights in real time to drive incremental and radical innovations.

Recent evidence by

Cardoso et al. (

2024), through a systematic review of open innovation in tourism, confirms that stakeholder collaboration across firms, governments, and academia remains a foundational mechanism in advancing innovative capacity in the sector. Likewise,

Rehman et al. (

2024) explore a multidimensional stakeholder approach to sustainable tourism development, demonstrating how open innovation initiatives require broad institutional coordination, public–private partnerships, and behavioral alignment.

Jutidharabongse et al. (

2024) add to this understanding by examining how management control systems and dynamic capabilities interact with open innovation strategies in tourism, especially under external pressures such as the COVID-19 crisis. Their findings reinforce the role of internal governance structures in operationalizing collaborative innovation.

These ten studies demonstrate that stakeholder engagement in tourism open innovation is neither optional nor peripheral. It is central to the co-creation of services, knowledge diffusion, and change legitimization, stressing that innovation ecosystems in tourism are fundamentally relational, dependent on trust, reciprocity, and shared value creation.

An important insight from this cluster is that stakeholder engagement enhances organizational adaptability.

Iglesias-Sánchez et al. (

2020) show that destinations that invest in open communication mechanisms are more responsive to emerging trends and crises, as collaborative knowledge exchange improves internal learning and strategic foresight (

Yeh & Ku, 2019).

Furthermore, these studies highlight the importance of intermediary actors, such as digital platforms, living labs, and customer interfaces, that enable interaction between otherwise disconnected stakeholders.

Lalicic (

2018) and

Nascimbeni et al. (

2017) illustrate how these mechanisms increase participation and innovation diversity.

Another recurring theme is the empowerment of non-traditional stakeholders.

Mengual-Recuerda et al. (

2021) and

Lalicic and Dickinger (

2019) show that customers, often considered passive recipients of services, play a proactive role in generating value through feedback and idea-sharing.

The cumulative insights of this cluster support the view that stakeholder engagement in tourism innovation must be institutionalized through precise governance mechanisms. Whether through formal structures like living labs or digital platforms, or informal networks of trust, engagement needs to be systematic and sustained.

These collaborative approaches support participatory governance, destination resilience, and innovation ecosystems driven by stakeholder input. The emphasis on stakeholder collaboration reflects the principles of stakeholder theory (

Freeman & McVea, 2001), particularly within tourism governance (

Dredge, 2006). Open innovation practices such as multi-actor engagement and shared data ecosystems demonstrate how inclusive governance fosters innovation. These practices also connect with community-based tourism innovation models (

Bramwell & Lane, 2011), which rely on inter-organizational trust and mutual benefit.

5.3. Employee Empowerment and Innovation Capacity in Tourism Firms (Nine Articles)

This cluster focuses on how internal organizational practices, particularly those involving employees, contribute to the effectiveness of open innovation in tourism. While “organizational innovation” may initially appear disconnected from tourism, several empirical studies demonstrate that tourism organizations, especially in hospitality, rely heavily on their workforce’s capacity to engage in, support, and co-create innovation.

Zhang et al. (

2022) provide compelling evidence that employees in the hospitality industry exhibit greater innovative behaviors when supported by open innovation environments. Their study highlights that such environments expose staff to external knowledge, collaborative practices, and idea-sharing platforms, fostering a culture of creativity and experimentation. This is particularly relevant in service-oriented contexts like tourism, where employee behavior directly influences customer experiences.

Khan et al. (

2021) further reinforce this argument by stating that the hospitality industry must transition from traditional hierarchical business models to innovation-driven and employee-centered approaches. Their research suggests that employees empowered to innovate during disruption are better equipped to deliver value under new service constraints. This adaptability is positioned as a core outcome of organizational open innovation.

Also,

Shin and Perdue (

2022) examine how hotel employees develop creative service ideas, particularly focusing on the role of empowerment and motivational mechanisms. Their findings suggest that when staff members feel heard and are given autonomy in their roles, they are more likely to contribute valuable ideas to the innovation process. These insights confirm that human capital is not just a passive recipient of innovation strategies, but an active driver of them.

Hameed et al. (

2021) offer a comprehensive model linking internal innovation capacity, external knowledge integration, and service innovation to business performance in the hotel sector. Their findings reveal that open innovation only yields significant results when employees have the necessary tools and environments to act upon external knowledge inputs; this positions employee competence as a mediating factor in the innovation–performance relationship.

Analyzing how process innovation capabilities relate to collaborative team performance,

Yeh and Ku (

2019) show that organizational learning, when supported by internal systems facilitating knowledge exchange, leads to more coherent and impactful innovation outcomes. This internal alignment is essential in the tourism industry, where service delivery is team-based.

From a different perspective,

Gusakov et al. (

2020) observe that open innovation in tourism increasingly depends on frontline employees who interface directly with customers. Their study emphasizes continual learning, digital literacy, and emotional intelligence, particularly in high-contact services such as hotels and guided experiences. They argue that investments in training and employee development must accompany the adoption of open innovation frameworks.

This argument is echoed in

Tuan (

2025), who finds that green entrepreneurial orientation, supported by open innovation and predictive analytics, positively influences employees’ contribution to sustainable performance in hotel firms. Similarly,

Luu (

2025) reveals that the effectiveness of big data in driving market pioneering is significantly enhanced when mediated by green open innovation strategies involving staff engagement and environmental responsibility.

Jutidharabongse et al. (

2024) also explore how management control systems, when aligned with open innovation strategies, enhance employee-driven dynamic capabilities, particularly under the pressure of external crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Their findings underscore the role of organizational design in supporting frontline innovation.

These studies offer a firm empirical grounding for including organizational innovation and employee behavior as a core cluster in tourism’s open innovation context. They establish that innovation is not simply the product of managerial decisions or technological inputs, but a collective, human-centered process rooted in the daily operations of service organizations. The behavioral engagement of staff becomes a determinant of how effectively external knowledge is translated into service innovation. Tourism organizations function as knowledge-intensive service environments, where employees’ roles are operational and creative.

Moreover,

Gusakov et al. (

2020) argue that digital transformation in tourism can only be successful when employees are digitally competent and institutionally supported. Their research highlights that innovation in tourism is increasingly contingent on digital fluency, which must be cultivated internally.

Another notable insight is the value of internal communication structures. Studies by

Yeh and Ku (

2019) and

Shin and Perdue (

2022) suggest that when internal feedback loops are robust, they improve coordination and amplify the visibility of frontline insights, which are often crucial to innovation. In this setting, leadership styles significantly influence employee participation in open innovation (

Khan et al., 2021;

Zhang et al., 2022). Transformational leadership is found to promote psychological safety and innovation readiness among staff, enabling more effective engagement with innovation initiatives.

In conclusion, the nine studies in this cluster establish that the organizational environment and employee dynamics profoundly shape open innovation in tourism. Investing in employee empowerment, knowledge sharing, and internal innovation capabilities is not peripheral, but foundational for achieving innovation outcomes in the sector.

In this context, open innovation empowers employees to contribute knowledge and ideas, increasing the internal innovation capacity of tourism firms. This cluster illustrates the internal dynamics of open innovation, where organizational learning and empowerment enhance innovation capacity. It reflects the theory of absorptive capacity (

Zahra & George, 2002), which posits that firms must acquire, assimilate, and apply knowledge to innovate. Empowered employees contribute to internal ideation and are instrumental in adapting external knowledge, particularly in service-dominant sectors such as tourism (

Sigala, 2018).

5.4. Digital Transformation and Innovation Resilience in Tourism (Nine Articles)

This final cluster combines nine studies emphasizing digital transformation and innovation resilience as central dimensions of open innovation in tourism. The capacity of tourism organizations to integrate technology and respond to crises through innovation mechanisms is at the core of this discussion. Collectively, these contributions highlight how digital tools, platforms, and intelligent systems shape the capacity of tourism enterprises to adapt, evolve, and compete in volatile contexts.

Gusakov et al. (

2020) provide an overarching view of how digitalization and open innovation intersect in the post-pandemic tourism industry. Their study underscores the acceleration of technological adoption due to COVID-19 and argues that open innovation platforms effectively respond to systemic disruptions. According to their findings, destinations integrating open innovation into their digital strategies are better equipped to rebuild trust and offer enhanced visitor experiences.

Stare and Križaj (

2018) explore how tourism firms employ digital technologies to create niche, personalized services. Their findings indicate that open innovation increasingly depends on digital infrastructure, enabling firms to co-create offerings with customers and other stakeholders.

He and Wang (

2016) present a process-based framework demonstrating how social media can support the innovation process in tourism. They argue that social platforms facilitate idea generation, diffusion, and refinement, especially when organizations systematically engage customers in innovation activities. This digital interaction becomes a strategic asset in service development. This integration enhances operational efficiency and deepens engagement.

Szromek and Polok (

2022) propose a business model for SPA tourism that integrates sustainability and innovation. Their research suggests that innovation resilience must be institutionalized, not merely improvised in response to crises. The authors advocate for a continuous and systemic open innovation approach that enhances long-term adaptive capacity, particularly in health-related and well-being tourism.

Gretzel et al. (

2015) examine the foundations of smart tourism, identifying open innovation as a key enabler of innovative destination ecosystems. Their work highlights that digital transformation is not solely technological, but also organizational and cultural, with data, connectivity, and real-time responsiveness being central to co-creative innovation in bright environments.

Liburd and Hjalager (

2010) contribute with an early but influential view on how digital learning platforms and knowledge resources support tourism innovation. Their research shows that innovation capacity can be expanded through collaborative learning environments, suggesting a shift towards distributed and digitally mediated knowledge exchange in tourism.

Recent findings by

Mota et al. (

2024) reinforce this idea, demonstrating that digital technologies in tourism enterprises can significantly increase competitiveness when linked to data-driven open innovation strategies. Their study also highlights the importance of digital literacy and cross-functional teams in maximizing innovation outcomes.

Similarly,

Rehman et al. (

2024) examine innovative tourism systems and confirm that open innovation mediates between digital transformation and stakeholder engagement. Their work suggests that tourism destinations capable of orchestrating digital networks are better positioned to enhance resilience and long-term value co-creation.

Lastly,

Shin (

2023) investigates the relationship between digital open innovation and hotel customer knowledge management. His findings underscore the importance of technological capabilities in integrating customer feedback and transforming it into service innovations that are both adaptive and scalable.

These studies confirm that digital transformation is more than an operational upgrade; it is a strategic imperative. Tourism organizations must increasingly rely on digital tools to reach markets, gather insights, co-create value, and respond to emerging challenges. One key theme standing out across these contributions is the role of crisis as a catalyst for innovation. Both

Gusakov et al. (

2020) and

Szromek and Polok (

2022) underscore that periods of disruption reveal structural weaknesses and simultaneously open windows of opportunity for innovation. Open innovation becomes a vehicle through which tourism organizations can redesign services and delivery models.

Another insight relates to the architecture of digital platforms.

Stare and Križaj (

2018) and

Gretzel et al. (

2015) show that innovation is increasingly embedded in digital ecosystems that connect suppliers, users, and institutions. These ecosystems facilitate the flow of data and knowledge necessary for rapid innovation cycles. Moreover, the studies collectively highlight the shift from reactive to proactive innovation. While digital adoption was initially driven by necessity, current trends point towards strategic digital integration as a sustained innovation practice (

Gusakov et al., 2020;

He & Wang, 2016).

In sum, the digital transformation and innovation resilience theme underscores that technology is both a tool and a context for open innovation in tourism. It enables operational efficiency, market reach, and the design of adaptive, co-created experiences that align with evolving consumer expectations and global uncertainties. Still, these contributions also call attention to the need for inclusivity in digital innovation.

Liburd and Hjalager (

2010) warn that technological access and literacy must be addressed to ensure that innovation remains open and participatory across diverse tourism actors.

Globally, this cluster reinforces the idea that open innovation in tourism cannot be dissociated from the digital transition. It must be understood as a multidimensional process that involves people, systems, and strategies, all working together to ensure that tourism remains competitive, resilient, and responsive to change. The analysis shows that two transversal dimensions are particularly relevant when examining the intersection between open innovation and the tourism industry: the role of the external environment and the integration of digital technologies, especially social media. Social media platforms emerged as critical channels through which tourism services acquire customer insights, foster engagement, and enable co-creative processes by acting as information sources and interaction spaces, reinforcing the open innovation model.

Open innovation enables the adoption of digital platforms and real-time feedback mechanisms, accelerating the innovation cycle and fostering greater adaptability. Digital transformation enables real-time feedback, user-driven innovation, and data-informed service adaptation. These patterns align with

Chesbrough and Bogers (

2014), who define digital infrastructures as key enablers of open innovation. Additionally, the integration of user-generated content and data analytics resonates with the work of

Gretzel et al. (

2015) on smart tourism ecosystems, where digital technologies enhance adaptability and system resilience.

To synthesize the findings of the review,

Figure 4 was developed to illustrate how the four thematic clusters contribute to open innovation outcomes in tourism. This visual representation offers an integrative view of the main innovation processes discussed and highlights their practical implications.

5.5. Cross-Cutting Reflections: Sustainability, Digitalization, and the Future of Open Innovation in Tourism

Beyond the four main thematic clusters identified, the literature reviewed reveals several transversal dimensions shaping the evolution of open innovation in the tourism sector. Among these, sustainability and digital transformation are critical paradigms that influence how innovation processes are being reconfigured to address contemporary challenges and future opportunities.

Although sustainability was not the primary focus in most reviewed studies, several contributions emphasize its growing relevance. For example,

Gusakov et al. (

2020) highlight how smart tourism destinations utilize open innovation to increase responsiveness to ecological and systemic challenges. Similarly,

Szromek and Polok (

2022) propose innovation-based models for spa tourism that integrate sustainable transformation and human well-being, reinforcing the link between innovation openness and environmental responsibility.

Rehman et al. (

2024) further underscore the potential of open innovation in shaping inclusive and eco-efficient tourism governance by integrating big data and stakeholder collaboration.

Jutidharabongse et al. (

2024) also draw attention to the role of open innovation in fostering resilience and sustainability performance in times of crisis, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

These studies collectively suggest that open innovation may function as a mechanism for enhancing competitiveness and a strategic platform for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) within the tourism sector. Co-creation, digital engagement, and knowledge sharing are increasingly used to design low-carbon, circular, and inclusive tourism services.

In parallel, the reviewed literature confirms that digital transformation remains a fundamental enabler of open innovation. From real-time feedback collection via social media (

He & Wang, 2016;

Shin, 2023) to the development of innovative, adaptive tourism ecosystems (

Gretzel et al., 2015), digital tools facilitate stakeholder participation and accelerate innovation cycles. Data analytics often reinforce these processes, which help firms to better anticipate trends, personalize experiences, and manage resources more efficiently.

A key challenge for scholars and practitioners will be to develop theoretical and empirical models that capture the intersection between open innovation, sustainability, and digitalization. These domains are not isolated, but mutually reinforcing sustainable innovation depends on participatory structures, while digital platforms serve as catalysts for open and inclusive innovation ecosystems. The ability of tourism organizations to integrate these dimensions will be decisive for their competitiveness and resilience in a rapidly changing global environment.

6. Conclusions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how open innovation has been empirically investigated in the tourism industry, offering well-grounded responses to the three central research questions. The evidence gathered across the four thematic clusters shows that the external environment, encompassing stakeholders, customers, and partners, is foundational in shaping open innovation dynamics. Similarly, incorporating digital technologies is no longer a peripheral strategy, but a structural enabler of continuous and collaborative innovation in tourism. This review confirms that open innovation delivers significant benefits for tourism organizations by enhancing collaboration, improving service innovation, and encouraging sustainable value creation.

Accordingly, this article confirms a growing academic interest in the topic and highlights the scarcity of in-depth research and theoretical consolidation in this domain. Despite its recent expansion, the relatively limited literature suggests fertile ground for further empirical investigation and conceptual development. Advancing research in this area will be crucial to fully understand how open innovation transforms the tourism sector and inform effective managerial and policy strategies.

The findings demonstrate that scholarly interest in the topic has intensified considerably over the past few years, with a noticeable increase in publications from 2019 to 2022, and a continuation of this trend into 2023, 2024, and early 2025. This reflects a growing awareness of the strategic value of open innovation in addressing the tourism sector’s structural and operational challenges. Nevertheless, the analysis also reveals that the empirical foundation of this research domain remains relatively limited. A predominance of recent studies characterizes the field, many of which are exploratory, and a need for broader methodological diversity. This observation directly addresses the first research question, highlighting that the current body of research, while promising, is still in its developmental stage and would benefit from further empirical consolidation.

Concerning the second research question, the review identifies multiple benefits of implementing open innovation in tourism. These include enhanced customer satisfaction, improved service quality, stronger destination branding, and increased organizational responsiveness. Open innovation facilitates the integration of external knowledge, particularly from tourists, residents, employees, and other stakeholders, into internal innovation processes, resulting in more authentic and co-created tourism experiences. Moreover, open innovation supports organizational learning, employee engagement, and interdepartmental collaboration, enhancing firms’ capacity to innovate consistently. The strategic use of digital platforms and social media further amplifies these benefits by enabling real-time interaction, feedback collection, and knowledge exchange between tourism actors.

Regarding the implications for future research, although the positive outcomes of open innovation are well documented, the empirical scope of the existing studies remains narrow regarding geography and methodological depth. Many studies focus on specific cases or contexts, offering valuable but localized insights. Expanding the empirical base through broader, comparative, and longitudinal studies exploring how open innovation practices evolve over time and across different tourism industry segments is essential to advance the field. Furthermore, greater theoretical refinement is needed to adapt open innovation concepts to the unique characteristics of tourism, particularly its experiential, co-creative, and relational dimensions.

In conclusion, the evidence collected supports that open innovation is applicable and highly beneficial to the tourism industry. It enables organizations to respond more effectively to changes, to co-develop value with diverse stakeholders, and to remain competitive in an increasingly dynamic and complex environment. However, further empirical research and theoretical development are required to fully harness its potential. The current findings provide a strong foundation for such efforts, highlighting both the opportunities and the pressing need to deepen the understanding of open innovation as a transformative force in tourism.

Furthermore, the findings underscore that open innovation can act as a catalyst for sustainable innovation. By encouraging collaboration and knowledge sharing, it enables the co-creation of solutions that address environmental and social challenges. Future studies should further explore how open innovation supports the development of eco-innovations in tourism, such as sustainable mobility, low-carbon accommodations, and regenerative tourism practices.

Moreover, this review offers a novel contribution by bridging open innovation theory and tourism studies through a thematic synthesis of empirical applications. While open innovation is well established in manufacturing and high-tech industries, its systematic integration in tourism remains underexplored. By identifying four innovation clusters and mapping their implications across tourism segments, this study advances our understanding of how openness fosters co-creation, resilience, and sustainable development within tourism ecosystems. In doing so, open innovation strengthens organizational resilience, accelerates digital adaptation, and contributes to the transition toward more inclusive and competitive tourism ecosystems.

6.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

This review offers significant implications for the tourism sector’s academic theory and managerial practice. Theoretically, it expands the scope of open innovation research by contextualizing its application in service-based and experience-driven industries. While open innovation has traditionally been associated with manufacturing and high-tech sectors, this study demonstrates its strong relevance in tourism, a sector characterized by high levels of stakeholder interaction, experiential co-creation, and service differentiation.

The review’s identification of four thematic clusters, destination branding and experiential value, stakeholder collaboration and co-creation, employee empowerment and innovation capacity, and digital transformation, offers a structured framework for theorizing open innovation in tourism. These clusters support the development of interdisciplinary models that integrate service-dominant logic (

Vargo & Lusch, 2008), stakeholder theory (

Freeman & McVea, 2001), and digital innovation paradigms (

Nambisan et al., 2017). Importantly, the findings reinforce the view of open innovation as a systemic and non-linear process through which internal capabilities and external inputs coalesce to generate adaptive and sustainable innovation trajectories.

From a managerial standpoint, the results offer targeted insights. First, managers should actively engage tourists, employees, residents, and institutional stakeholders as co-creators of value, particularly through participatory branding and community-based initiatives. Second, empowering employees—particularly frontline staff—with the autonomy and tools to contribute to innovation enhances internal responsiveness and organizational learning. Third, digital platforms should be adopted for promotion and as strategic instruments for ideation, feedback collection, and collaborative solution development. Finally, open innovation should be seen as a strategic enabler of sustainability, allowing organizations to co-design greener services and more inclusive governance practices.

Therefore, managers are encouraged to establish open organizational cultures that reward transparency, experimentation, and knowledge sharing. Investments should be made in innovation management systems that capture both internal insights and external signals in real time. Open innovation becomes a powerful strategy to address today’s tourism environment’s volatility, complexity, and sustainability imperatives when supported by appropriate digital infrastructure and leadership commitment.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

This section discusses both the limitations of the current review and the emerging research directions in the field of open innovation in tourism. It aims to provide a roadmap for future investigations and theoretical refinement based on the identified gaps and evolving trends in the literature. The selection of studies was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles published in English and indexed in Scopus, which may have excluded relevant research published in other databases, in different languages, or gray literature such as industry reports. This restriction, although deliberate to ensure academic quality, may have narrowed the representativeness of the findings. Though thematically rich, the final sample of 35 articles reflects a relatively limited empirical base. Most studies adopt qualitative and exploratory designs, often relying on single-case studies or context-specific analyses. As such, generalizability remains constrained, and causal relationships are rarely established. Future research would benefit from more diverse and rigorous methodologies, including quantitative approaches, mixed methods, and longitudinal studies examining open innovation strategies’ long-term impacts.

Future studies should focus on several promising areas, such as the integration of open innovation with sustainability and regenerative tourism, the role of digital and data-driven platforms in fostering collaboration, and the adaptation of open innovation models in resource-constrained contexts like SMEs or rural tourism. There is also a need to explore how governance mechanisms, such as public–private partnerships and participatory decision-making, support innovation openness and resilience in different tourism ecosystems.

Another relevant limitation concerns the conceptual fragmentation observed across the literature. While the four thematic clusters identified in this review offer a helpful structure, the absence of shared theoretical models highlights the need for conceptual refinement. Future research should seek to build more coherent and tourism-specific frameworks for understanding open innovation, particularly frameworks that integrate service-dominant logic, stakeholder theory, and digital transformation.

Finally, although no geographic limitation was imposed in the search process, the reviewed studies predominantly focus on European and East Asian contexts. Future research should therefore expand the geographic scope and contextual diversity to include underrepresented regions and tourism realities. Studies are concentrated in specific regions or destination types, which limits our understanding of how open innovation operates across different cultural, institutional, and economic contexts. Future research should explore applications in diverse tourism segments and settings, such as rural destinations, emerging markets, or heritage tourism, to gain a more comprehensive picture of innovation practices and outcomes.