1. Introduction

Traditional Portuguese gastronomy is a pillar of national identity, incorporating Portugal’s cultural, historical, and social fabric. Recognised as an intangible cultural heritage, Portuguese cuisine is more than a collection of recipes; it reflects centuries-old traditions, regional diversity, and the harmonious fusion of influences stemming from its maritime history. Safeguarding this culinary heritage preserves the cultural identity of Portugal and plays a significant role in promoting tourism and economic growth.

Portuguese gastronomy is a vibrant tradition passed down through generations, deeply rooted in regional history and practices. Iconic dishes such as cod à Brás, caldo verde (green broth), seafood rice, and the famed pastéis de nata (from Belém in Lisboa) reflect the historical and geographical diversity of Portugal, from coastal fishing communities to the agricultural heartland. This cuisine is intrinsically linked to festivities, religious celebrations, and family gatherings, featuring, for instance, the centrality of sardines in the popular festivals of São João, S. Pedro, and Santo António. At the same time, Easter traditions showcase dishes such as roast goat or a variety of folar, sweet and adorned with boiled eggs in the south, and salty with various types of meat in the north. Moreover, each region possesses a unique culinary identity; for example, Porto is celebrated for its francesinha and Porto-style tripe, Alentejo for its açordas, and the Algarve region for its cataplana dishes, which often feature fish and/or seafood. Preserving these regional variations is vital to ensuring that they are not lost in an increasingly globalised world.

Koerich and Müller (

2022) define gastronomy as a multifaceted field encompassing food culture, cooking, product offerings, service management, and organisational structures. It highlights gastronomy’s dynamic and evolving nature, which operates through multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinary connections with various related areas, reflecting its complexity.

Almansouri et al. (

2022) emphasises the importance of authentic recipes, local ingredients, and knowledgeable chefs in preserving cultural heritage. In turn,

Partarakis et al. (

2021) highlighted the role of traditional food practices in shaping cultural identity and preserving heritage.

The northern region of Portugal was selected for this research due to the diversity of traditional Portuguese gastronomy, the various preparation methods, and the cultural differences that may suggest different approaches to the theme.

The selection of Porto for the preparation of this study is based on the fact that we consider that the historical city centre has a traditional gastronomic offer, and this city centre has tourists and Portuguese residents from all over Portugal, in particular the North of Portugal. The literature review mostly addresses tourist-focused research, with limited attention paid to residents’ perceptions. This study shifts the focus by exploring how residents perceive and value gastronomy as part of their cultural identity, addressing this gap in existing research. Therefore, this study aims to understand the Portuguese residents’ perceptions regarding recognising gastronomy as a cultural heritage and preservation for tourism development in Porto and its neighbouring municipalities in northern Portugal, and to group them into factors to more comprehensively understand the different perceptions.

Portuguese residents’ roles are essential, as they are the custodians of these practices and traditions, and contribute to preserving cultural authenticity.

To achieve this purpose, structured questionnaires were distributed to residents, employing a convenient selection of respondents from the North of Portugal as a sampling approach in popular urban tourism areas of Porto between May and October 2022. This resulted in the collection of 262 valid responses. We aim to contribute to a better understanding of how residents in this geographical area perceive the importance of traditional gastronomy, both as a cultural value and as a factor that helps preserve memories and traditions. Furthermore, it is an attraction for tourists and can significantly contribute to the sustainability of tourism and heritage.

This research is organised into several main sections. The introduction outlines the research objectives and provides the context. This is followed by a literature review establishing a theoretical framework related to the themes examined. The methodology outlines the methods employed to collect and analyse the data. The data analysis discusses the results and compares the findings with the existing literature. Lastly, the recommendations and conclusions underscore the practical implications and suggest avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review

Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) encompasses the living traditions inherited from our ancestors and transmitted across generations. These include representations, expressions, knowledge, skills, related instruments, objects, artefacts, and cultural spaces. ICH manifests in several domains, such as (a) oral traditions and expressions, including language; (b) performing arts; (c) social practices, rituals, and festive events; (d) knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe, and (e) traditional craftsmanship (

UNESCO, 2003). Together, these elements signify the intangible cultural heritage of a community, emphasising its distinctive traditions, values, and ways of life. This represents a significant step toward acknowledging different forms of heritage, transcending the physical and tangible aspects, including gastronomy. For this Convention, ICH is continuously recreated in response to the community environment, interactions with nature, and historical influences, fostering a sense of identity, continuity, and respect for cultural diversity and creativity. Therefore, it is fundamental to safeguard this intangible heritage through measures that ensure its viability. These measures include identification, documentation, research, preservation, protection, promotion, enhancement, and transmission, primarily through formal and non-formal education and the revitalisation of various aspects of this heritage.

Holistic strategies for safeguarding, maintaining, and conserving heritage require a unique approach that incorporates the study of local history, appreciates community values, and recognises the relationship between natural environments and cultural traditions (

Tricarico et al., 2023). From another perspective,

Santamarina (

2023) critiques cultural heritage management within market-driven systems, advocating for a more ethical and protective approach, particularly concerning intangible cultural expressions. The author emphasises the need to redefine priorities and frameworks, shifting the focus away from profit-driven motives (managing the ‘brand’) and toward safeguarding and preserving the true essence of heritage.

Gastronomy is a fundamental aspect of our daily lives, transcending mere necessity to become an essential cultural element. Food is intrinsically linked to well-being, sensory perceptions, and human behaviour in gastronomic experiences. As

Duman and Avcıkurt (

2023) highlight, cuisines blend tangible and intangible elements that embody a region’s identity. The intangible aspects include sensory and cultural dimensions, such as distinctive flavours and aromas, which are more challenging to capture. These elements hold profound cultural significance, representing a community or region’s history, values, and traditions.

It is also acknowledged as enhancing tourists’ experiences. Sustainable tourism conserves resources and enriches visitors’ experiences, influencing their satisfaction, loyalty, and future behaviour, which are vital aspects of tourism management (

Ramazanova et al., 2025). Local cuisine is a crucial component of a region’s cultural heritage, enhancing the image of tourist destinations (

Okech, 2014). Similarly, gastronomy promotes sustainable tourism by emphasising local ingredients, minimising environmental impact, and supporting smallholder farmers, fishermen, and producers. This approach attracts eco-conscious tourists and aids in preserving rural livelihoods, as well as regional and traditional cuisine. According to

Stalmirska (

2024), local food strengthens destination marketing, community pride, and cultural identity, but realising its full potential requires better support, clear guidelines, and stronger governance to enhance tourism sustainability. Urban destinations widely use food marketing strategies to strengthen their positioning within the highly competitive tourism market. In turn,

Park and Widyanta (

2022), in the context of emerging food tourism destinations, emphasise that creating new food experiences and expanding gastronomic offerings require the adoption of a holistic approach to food tourism development. Food is important for urban, developing, and emerging tourism destinations, forming an integral part of their cultural identity, visitor experience, and destination marketing strategies. As such, it has been widely recognised as a means of expression and cultural interaction, and in recent years, the consumption of typical dishes while visiting a destination has gained increasing relevance. In addition, food represents an important tool for promoting a local cultural identity to visitors (

Garibaldi & Pozzi, 2018), contributing to the construction and strengthening of a destination’s image, creating sustainability, and potentially influencing the behavioural intentions of tourists (

Y. Lin et al., 2011).

Tourism has increasingly explored gastronomy as a strategic marketing resource and branding tool (

Kivela & Crotts, 2006). Food tourism is growing globally, with tourists seeking unique dining experiences. For some destinations, it plays a central role in providing enriching, authentic, and memorable tourist experiences (

Williams et al., 2019), particularly standing out for its authenticity. Genuine cuisine can be a decisive factor in the selection of a destination. It should not be underestimated when areas seek to reshape their image and boost tourism development, especially those whose economies rely heavily on this sector (

Hiamey et al., 2021).

Ritual cuisine, a subset of intangible cultural heritage, involves the preparation and consumption of food as part of traditional rituals and ceremonies. It encompasses representations, knowledge, and skills from a community and symbolises local cultural expressions (

Ramazanova et al., 2022a). Its symbolic nature and cultural significance lie in how it embodies and reflects a community’s core values, beliefs, and identity. These culinary traditions handed down through generations incorporate specific ingredients, cooking methods, and presentation styles that hold special significance for the community. They encompass aspects such as traditional cuisine, regional peculiarities, and the typical foods of a particular geographical area (

Ramón Fernández, 2020).

Almansouri et al. (

2022) emphasises that gastronomy comprises three key dimensions: Legacy, which includes ‘inheritance’ and ‘authenticity of the recipe and cooking’; Place, linked to the ‘locality of ingredients’; and People, represented by ‘knowledgeable chefs who embody their culture’. Additionally,

Almansouri et al. (

2022) identify three authenticity risk factors: ‘adaptation to customer preferences’, ‘costs of ingredients’, and ‘non-native origin of chefs’.

Partarakis et al. (

2021) highlight the significance of traditional food production and consumption practices in shaping a society’s cultural identity, which is crucial for preserving cultural heritage, identity, and values.

Traditional gastronomy is deeply connected to the rituals of eating. Certain foods are often prepared and consumed during religious ceremonies, festivals, and life milestones, such as weddings and family gatherings (

Ramazanova et al., 2022a). These practices help in preserving and reinforcing the continuity of social and cultural traditions. In this way, ritual gastronomic practices transcend mere sustenance, serving as a powerful medium for expressing and safeguarding a community’s unique cultural heritage.

As

Brumberg-Kraus (

2020) notes, eating rituals can be categorised by their form and sequence, function, the emotions they elicit, and their meaning, and reinforce the idea that these rituals imbue eating experiences with affective, cognitive, social, cultural, and religious significance. Gastronomy shapes symbolic cultural heritage, bridging a community’s identity and historical roots. According to

González Rodríguez and Campos Medel (

2023), attachment to local societies is strengthened through belonging, acceptance, and a sense of rootedness. In essence, these factors collectively contribute to the cultural fabric of a community.

To preserve a place’s intangible heritage, it is essential to design methodologies that facilitate a closer analysis of its sites, people, and symbolic content. This highlights the significance of cultural heritage and underscores its thoughtful preservation efforts.

Traditional cuisine deserves special attention due to its symbolic nature and cultural significance, encapsulating a community’s values, beliefs, and identity. Furthermore, the literature on this topic remains scarce, and ongoing debate surrounds it.

Miguel Molina et al. (

2016) note that, while research on intangible heritage has expanded, the academic exploration of gastronomy as intangible heritage remains limited, highlighting a promising avenue for interdisciplinary study. Their bibliometric analysis suggests that, although interest in intangible heritage is growing, the focus on gastronomy as a cultural asset is still nascent. Defining gastronomic heritage more clearly could play a crucial role in preserving its essential elements and boosting its appeal as a driver of local tourism.

3. Materials and Methods

This article’s empirical research addresses the city of Porto and neighbouring municipalities in the North of Portugal, evaluating Portuguese residents’ perceptions of the recognition of gastronomy as a cultural heritage and tool for tourism development.

Porto has a history and is classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which underlines the importance of this study due to the constant growth in the number of tourists during the last decade (

Silva et al., 2024). The classification of World Heritage has contributed to the recognition of the landscape and cultural heritage, including gastronomy. It has also increased the number of tourists visiting the destination (

Ramazanova et al., 2022b).

One of the primary objectives of this research was to analyse Portuguese residents’ perceptions of the recognition of gastronomy as a cultural heritage and its role as a tool for tourism development in Porto and the neighbouring municipalities of Northern Portugal. To achieve this, we used a questionnaire-based methodology to collect quantitative data.

Data were collected by conducting questionnaires with residents using a convenient sampling approach in Porto’s historical city centre from May to October 2022. Before data collection, pilot testing with 15 respondents was conducted to assess the clarity of the questions, the overall structure of the questionnaire, and the time required to complete it. All respondents’ comments and suggestions were incorporated into the final version of the questionnaire.

The respondents were selected from Portuguese residents in northern Portugal who visited the historical city centre. The researchers selected a convenient sampling approach due to its several benefits; for example, it consumes requires less effort to select participants compared with other non-random sampling techniques, at a very low cost and in less time, given that the sample is taken from the population, which is available and accessible to researchers (

Golzar et al., 2022). Although convenience sampling has some limitations, efforts were made to ensure some diversity in the sample. For this purpose, different locations and periods were chosen to reach people of various age groups, occupations, and backgrounds as much as possible, given the context. All efforts resulted in 262 valid responses from Portuguese residents.

The questionnaire was prepared collaboratively by undergraduate students in tourism and hospitality and their supervising professors at Portucalense University.

Given the role of residents as custodians of gastronomy (

UNESCO, 2003), we employed questionnaires to capture their perceptions in two main sections, the first focusing on the sample profile and the second focusing on the evaluation of gastronomy, exploring the intersection between gastronomy, culture, heritage, and identity. The importance of preserving traditional dishes was emphasised, and concerns about globalisation contributing to the loss of traditional dishes were raised. The potential for cultural attractiveness through innovative approaches in the field of tradition is also highlighted.

To evaluate residents’ perceptions, respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Totally Disagree) to 5 (Totally Agree). Most of the attributes employed in this survey were derived from the works of

M. P. Lin et al. (

2021),

Miguel Molina et al. (

2016),

Partarakis et al. (

2021),

Ramazanova et al. (

2022b), and

Seyitoğlu and Ivanov (

2020), who have made vital contributions to the scientific dialogue on this topic that were further complemented by the contributions of the authors of this paper.

The data collected for this study were analysed employing both Excel and SPSS software. Excel was used for initial data organisation, and then the data were imported into SPSS 26. Sescriptive statistics were used to characterise the sample, providing an overview of the sample profile. Afterwards, the principal component analysis was employed to reduce the response profiles into synthesised responses regarding the assessment of gastronomy as an Intangible Cultural Heritage.

4. Results and Data Analysis

4.1. Sample Profile

The demographic characteristics of the 262 respondents (

Table 1) indicate that the gender distribution in this sample was relatively balanced. However, there was a slight predominance of men (52%) compared with women (48%). This balance reflects diversity and reasonable representation both men and women.

The sample was composed mainly of young adults, with 53% of respondents being 18–29 years old, 30–39 years old, and 40–49 years old, with 15% in each age range. This value can be relevant to understanding the respondent’s profile, such as their life stage, possibly at the beginning or middle of their career.

Most respondents (63%) were single, which may have been related to their young age, a phase in which many people are unmarried or in stable unions. Married people represented just over a quarter of the sample (27%), while divorced and widowed people were minorities, accounting for 8% and 2%, respectively.

Regarding education, most of the sample had a medium or high level of education. Most individuals had a Bachelor’s degree (35%) or 12th grade (35%), followed by respondents with a Master’s degree (10%). Analysing more details, we found that 70% of the participants held at least a 12th-grade or Bachelor’s degree (high school or higher). The most advanced levels (Master’s, Postgraduate, and Doctorate) represented 17% of the sample, which reveals a group with considerable academic training. Only 13% had a maximum grade of the or 9th grade, indicating a minority with more basic qualifications.

The analysis of attendee occupancy revealed some interesting trends. Private organisations (37%) and students (34%) represented the two largest groups. This indicated an active sample in the private and training labour markets. Civil servants corresponded to a small fraction (11%), as did entrepreneurs (7%). Retirees and those in unspecified categories (Others) added up to 6% each, being the smallest and least major groups.

The results reveal a diverse sample of gender, academic background, and occupation. However, a profile of young adults who are single and have at least completed secondary education predominates. The significant presence of students and workers from the private sector suggests that the sample reflects an active population in personal and professional development.

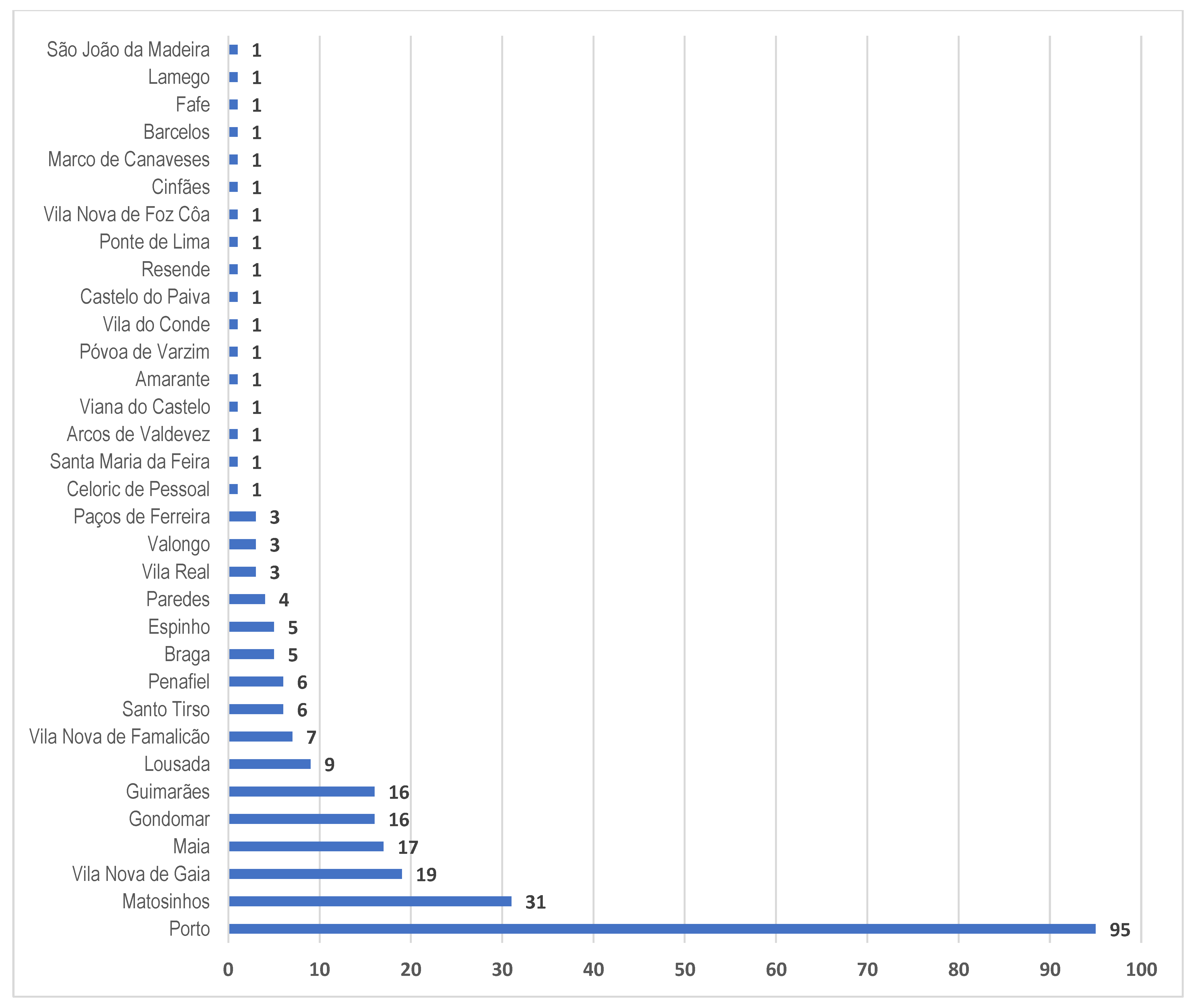

The analysis of

Figure 1 regarding the respondents’ municipality of residence was organised by groups of municipalities and associated percentages, detailing the main trends and possible inferences.

A detailed analysis indicated that the municipality of Porto stood out as the most frequent place of residence of the respondents, representing 36.3% of the total (95 individuals), which reflects its centrality in the North region. This result reflects the centrality of Porto, which, as the central city in the North region, concentrates a significant population and services, attracting permanent and temporary residents. Matosinhos comes in second place, with 11.8% (31 individuals), a considerable percentage attributed to the geographical proximity and socio-economic dynamics shared with Porto. Vila Nova de Gaia occupies the third position, with 7.3% (19 individuals).

Municipalities such as Maia, Gondomar, and Guimarães had percentages between 6.5% and 6.1%, reinforcing the influence of the Metropolitan Area of Porto (AMP).

Other municipalities, such as Lousada, Vila Nova de Famalicão, Santo Tirso, Penafiel, Braga, and Espinho, varied between 3.4% and 1.9%, while Paredes, Valongo, Paços de Ferreira, and Vila Real registered values between 1.5% and 1.1%.

More distant municipalities, with only 0.4% of respondents (1 individual each), included more distant locations or lower population density, such as Celorico de Basto, Santa Maria da Feira, Arcos de Valdevez, and Viana do Castelo, among others. The presence of these municipalities in the table may be related to occasional displacements or specific factors that led to the inclusion of inhabitants of these localities in the sample; however, their overall representativeness was small.

Overall, two-thirds of the respondents were from the Porto Metropolitan Area, but one-third were from other municipalities in the North of Portugal. Thus, most respondents lived in municipalities integrated into the metropolitan area of Porto or nearby, evidencing an apparent centrality of the city of Porto in the residential and population dynamics. However, the presence of more distant municipalities, although residual, suggests that the scope of this study included a significant territorial diversity, covering both urban and rural regions.

4.2. Results of Principal Component Analysis

This section presents the principal component analysis, which aims to reduce the response profiles into synthesised and orthogonal responses (

Table 2). In this context, 16 items related to gastronomy through the lens of residents were assessed. An exploratory factor analysis, using a varimax rotation with principal component analysis (PCA) extraction, was conducted to group these items into smaller factors that explain residents’ assessment from various perspectives. Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy were used to evaluate the suitability of applying factor analysis.

The KMO measure of sampling adequacy indicates the proportion of variance in the variables that might be attributable to underlying factors. High KMO values suggest a significant correlation between the original variables, indicating that factor analysis could be appropriate. In our study, the KMO and Bartlett’s test results (0.841 and

p < 0.001) demonstrated that applying factor analysis was appropriate (

Napitupulu et al., 2017).

PCA revealed the presence of four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0, explaining 55% of the cumulative variance (

Table 3). The rotation varimax was used to display the loadings, and variables loaded at a correlation level of 0.5 were included in the analysis (

Hair et al., 1995).

Concerning the reliability of the factors, Cronbach’s alpha was employed to assess the reliability of the extracted factors. The Cronbach’s alpha values exceeded 0.65 for factors 1, 2, and 3, which met the recommended threshold of 0.7 (

Nunnally, 1978) and indicated acceptable levels of internal consistency for these factors. To preserve the exploratory power of the extracted factors, factor 4 was retained for this analysis, despite its reliability being 0.47, as it demonstrated acceptable factor loadings and an eigenvalue greater than 1 (

Kaiser, 1974). From a theoretical perspective, it is essential to consider this factor as it offers significant insight into the conceptualisation of gastronomy. Factor 4 relates to the respondents’ perceptions of gastronomy as a concept not associated with heritage, but rather with modern cuisine, referring to the fact that traditional recipes can be changed over time. Traditional and modern kitchens should be the target of fusion to create new experiences for customers. This shows that gastronomy is a dynamic and evolving practice, distinct from traditional culinary heritage. Thus, its theoretical significance justifies its inclusion in the analysis.

Factor 1, labelled

Gastronomy, Tradition, and Identity (

M. P. Lin et al., 2021), underscores the appreciation of traditional gastronomy as a vital component of cultural identity and the concern for its preservation. The results indicate the importance of passing down traditional dishes to future generations, educating young people about gastronomic traditions, and involving the local community in conservation efforts. There is also concern regarding the loss of traditions due to globalisation. The connection between gastronomy and tourist products is positive, reinforcing the significance of integrating tradition into tourist events and services. Gastronomy is regarded as a cultural and economic pillar, essential for maintaining local identity and a tool for tourism development.

The second factor is

Gastronomy and Technology (

Pérez-Rodrigo & Aranceta-Bartrina, 2021), where innovation in traditional cuisine influences its cultural appeal, and preserving traditional recipes is highly valued. Publication in cookbooks is regarded as the best form of preservation, followed by digitising recipes through videos and photographs.

The third factor is called

Gastronomy and Daily Life (

Zábrodská, 2017), stressing the importance of traditional dishes prepared during weekends and holidays when more time is available. The daily preparation of traditional dishes is also considerable, although it occurs less frequently. In summary, cooking traditional dishes is often linked to leisure moments, although it remains a part of the routine for some individuals, albeit to a lesser extent.

Factor 4, named

Concept of Gastronomy (

Koerich & Müller, 2022), reveals that many participants believe that traditional recipes can evolve over time and that the fusion of traditional and modern cuisine presents an engaging way to create gastronomic experiences. The connection of gastronomy with modern cuisine is more significant than traditional cuisine, reflecting a trend towards innovation and adaptation.

In summary, there is a growing appreciation for the fusion of tradition and modernity, with traditional cuisine viewed as something to be modified or combined with contemporary approaches.

The principal component analysis (PCA) findings present a nuanced understanding of the interplay between gastronomy, cultural identity, and technological innovation. The four identified factors—Gastronomy and Tradition and Identity, Gastronomy and Technology, Gastronomy and Daily Life, and the Concept of Gastronomy—collectively underscore the significance of traditional culinary practices in preserving cultural heritage while adapting to contemporary influences. Factor 1 highlights the crucial role of gastronomy in preserving cultural identity and promoting community engagement, particularly in the context of globalisation. This is consistent with the perspective that traditional cuisine constitutes a vital economic and cultural pillar for tourism development and local identity. Furthermore, the second factor elucidates the dual function of technology in preserving traditional recipes, indicating a shift towards digital methods of documentation and promotion. Participants acknowledge the importance of tangible and digital preservation methods, suggesting that the future of gastronomy resides in a harmonious integration of tradition and innovation. The third factor illustrates the incorporation of traditional dishes into daily life, particularly during leisure periods, while the fourth factor denotes a burgeoning trend towards the fusion of traditional and modern culinary practices. This evolving appreciation for gastronomic innovation signifies a dynamic culinary landscape that values both heritage and creativity. These findings offer valuable insights for stakeholders in gastronomy and tourism, highlighting the necessity of strategies that honour traditional practices while embracing modernity.

In conclusion, the findings derived from this study illuminate a complex tapestry of perspectives regarding gastronomy, which encompass elements of tradition, technology, daily life, and innovation. The interplay among these factors underscores the significance of preserving culinary heritage while embracing contemporary advancements. This suggests that the future of gastronomy is grounded in the harmonious integration of both dimensions. This comprehensive insight may inform stakeholders within the culinary and tourism sectors, guiding strategic initiatives that honour traditional practices while fostering innovation and sustainability in gastronomic tourism.

4.3. Discussion

Factor 1 emphasises the role of traditional gastronomy in cultural identity and its preservation. It highlights the importance of transmitting gastronomic heritage to younger generations through education and community involvement, ensuring that traditional dishes and food practices are maintained and valued as part of a region’s cultural legacy.

The study by

Paunić et al. (

2024) aligns with our results. The first factor was labelled as geographic and cultural characteristics of gastronomy, emphasising authenticity, uniqueness, and the cultural integration of local gastronomic traditions in creating a rich gastronomic experience for tourists. The authors defined another factor related to gastronomic events, which promotes local products, cultural traditions, and sustainable tourism, offering tourists diverse opportunities, such as engaging in local dish preparation and familiarising themselves with the local gastronomic culture and tradition.

Hammou et al. (

2020) conducted a study on promoting Marrakesh handicrafts through social media, highlighting that communication is crucial for promoting products, particularly among the younger generation. They pointed out that social media communicates intangible cultural heritage, enabling its transmission, safeguarding, and promotion.

Ramazanova et al. (

2022a) explored the role of gastronomy as an intangible cultural heritage and its preservation through the analysis of international platforms, such as the International Institute of Gastronomy, Culture, Arts and Tourism (IGCAT), UNESCO Creative Cities Network, and UNWTO #TravelTomorrow, as well as its presence on social media. The results show the worldwide coverage of the topic; however, there is variability among world regions. Additionally, it demonstrates that the preservation of this heritage aligns with current trends, such as digitalisation processes, which facilitate its promotion and preservation.

The second factor, gastronomy and technology, reflects how technological innovation enhances the cultural significance of traditional gastronomy. It demonstrates that, while modern techniques are embraced, there is a strong emphasis on maintaining the authenticity of traditional recipes, balancing innovation with the preservation of culinary heritage. Nowadays, digitisation has become a popular tool for promoting traditional cuisine globally. According to

Thirumoorthi and Sedigheh (

2019), online marketing and social media platforms can help to promote gastronomic tourism by supporting its preservation and promotion. It is also noteworthy that participants refer to tangible methods, such as books, and acknowledge their importance in documenting and disseminating traditional recipes. Our results validate Almansouri’s ‘Legacy’ and ‘People’ dimensions, while highlighting technology as a new preservation axis.

The third factor, gastronomy and daily life, highlights how traditional dishes are especially valued during weekends and holidays when people have more time to cook. Although these meals are also prepared on regular days, they occur less frequently, indicating a link between time availability and culinary tradition. For instance, in Italy, dishes such as lasagna or ossobuco are typically reserved for Sunday meals or special occasions due to their lengthy preparation process (

Montanari, 2006). Similarly, tamales are commonly prepared in Mexico during Christmas and Día de los Muertos, symbolising familial bonding and cultural heritage (

Pilcher, 2012). In Czech households, traditional meals such as svíčková na smetaně (marinated beef with cream sauce) are also more often prepared on weekends or holidays, reflecting the time and effort required (

Zábrodská, 2017).

The everyday preparation of traditional dishes is significant, although it occurs less frequently. For example, in Japan, simple traditional dishes like miso soup, rice, and grilled fish continue to feature regularly in daily meals, demonstrating how culinary heritage adapts to modern lifestyles (

Cwiertka, 2008). Cooking traditional dishes is often associated with leisure time; however, it remains part of the routine for some individuals, albeit to a lesser extent.

Factor 4, the concept of gastronomy, demonstrates that participants view gastronomy as dynamic, supporting the evolution of traditional recipes. Factor 4’s low Cronbach’s alpha (0.47) is also noted. From a theoretical perspective, and considering the evolving nature of the concept, it is crucial to acknowledge this factor, as it offers significant insight into the conceptualisation of gastronomy. Factor 4 relates to respondents’ perceptions of gastronomy as a concept not tied to heritage, but to modern cuisine, indicating that traditional recipes can be altered over time. Traditional and modern cuisine appeal strongly, emphasising modern influences and highlighting a shift toward innovation and creative reinterpretation in contemporary culinary practices. However, according to previous studies, there is no standard definition of gastronomy. According to

Koerich and Müller (

2022), “gastronomy represents a field of studies and production activities, organisation of environments, service provision, management, product offerings, and performances in the context of food culture, which basically is centred on cooking and includes products, organisations, establishments, which, in a multi, inter, and transdisciplinary relationship with these areas” (

Koerich & Müller, 2022, p. 1). This definition reflects the multi-dimensionality of the concept, its complexity, and its evolving nature.

In tourism, destinations increasingly recognise the importance of their gastronomic offerings as a key part of their tourism product and adapt their cuisine to meet tourism demand. Thus, it becomes a challenge for chefs to strike a balance between meeting the expectations of tourists and preserving the integrity of traditional cuisine. From another perspective, innovation in the kitchen is evident, although most participants value the preservation of traditional recipes; a growing trend towards the fusion of traditional and modern cuisine is also apparent. The possibility of adapting traditional recipes to new contexts is well accepted, reflecting a willingness to innovate while respecting the authenticity of culinary practices. We can observe this reality in the modern health context of the Mediterranean diet, where classic dishes from Greek and Italian cuisines have been adapted to include healthier options, such as reducing fat or using plant-based alternatives. Nutrition trends have led to changes in traditional recipes, aiming for broader appeal without compromising core elements like olive oil, grains, and herbs. As a cultural model for dietary improvement, the Mediterranean diet is praised for its health benefits and palatability (

Nestle, 1995).

5. Conclusions

As an aspect of intangible cultural heritage, traditional Portuguese gastronomy plays a crucial role in shaping national identity, reflecting history, regional traditions, and various influences over the centuries. The research conducted in Porto and its surrounding municipalities underscored the significance that residents attribute to preserving traditional gastronomy as a cultural value and a strategic asset for the region’s tourist and economic development. The data analysis revealed a strong appreciation for gastronomy as a cornerstone of cultural identity. Most participants acknowledged the importance of passing on traditional dishes to future generations and educating young people about traditional cuisine, particularly considering the growing threat of globalisation, which can result in the loss of traditional practices.

Ren and Fusté-Forné (

2024) reached a similar conclusion, asserting that, within the context of tourism, the creation of food experiences is crucial for showcasing and redefining a region’s identity and relationship with the environment.

In this regard, gastronomy is an essential element for preserving cultural memory and a powerful tool for attracting tourists. As

Moreno Quispe and Hernández Rojas (

2025) conclude, gastronomy has become a key element in effectively managing and promoting tourist destinations.

This investigation also highlighted the potential of gastronomy to strengthen the connection between tourism and local culture, with many residents recognising the importance of integrating traditional dishes into tourism events and services. The relationship between gastronomy and gastronomic tourism was well-received and considered a practical approach to promoting sustainable economic development while preserving cultural authenticity.

Ren and Fusté-Forné (

2024) emphasise that such culinary experiences contribute to the preservation and reinterpretation of local traditions, employing innovative strategies to ensure that cultural identity remains relevant and captivating for visitors. As

Medina-Viruel et al. (

2019) conclude, the authenticity of culinary heritage plays a growing role in attracting tourists, acting as a significant driver for travel to World Heritage sites. They emphasise the importance of gastronomy in promoting cultural identity and enhancing the allure of these destinations.

Regarding innovation in the kitchen, although most participants value the preservation of traditional recipes, a growing trend towards the fusion of traditional and modern cuisine is evident. The possibility of adapting traditional recipes to new contexts was well-accepted, reflecting a willingness to innovate while respecting the authenticity of culinary practices. Technology, such as cookbooks and digitising traditional dishes, was also noted as an important strategy for documenting and preserving authentic recipes. In everyday life, gastronomy revealed that many Portuguese people cook traditional dishes during weekends and holidays, suggesting that these recipes continue to be prepared and enjoyed, especially for leisure and conviviality. However, the daily routine does not always include preparing these dishes, which may reflect changes in eating habits and the time available for preparing more traditional meals. The research conducted by

Villacrés et al. (

2025) expands on the topic, highlighting the impact of globalisation on cultural identity, including its influence on gastronomy. This study concludes that there is a significant decline in the intergenerational transmission of cultural heritage, with elders voicing concerns over the younger generation’s diminishing interest in traditional practices.

Ultimately, the findings of this research highlight the importance of promoting gastronomy as a cultural and economic asset, preserving traditional recipes while allowing for their evolution through innovation and adaptation to contemporary times. Public policies and private initiatives must continue to collaborate in integrating gastronomy within the tourism framework, ensuring that, while preserving cultural identity, it contributes to the sustainable and inclusive development of the Porto region and northern Portugal.

This study contributes to the existing literature by shifting the focus to how residents perceive and value gastronomy as a part of their cultural identity. It addresses a gap in research focusing on tourists’ perspectives (

Kivela & Crotts, 2006).

Our study aligns with that of

Koerich and Müller (

2022), emphasising the dynamic nature of gastronomy. It demonstrates how digitisation preserves gastronomy, highlighting technology’s role in syncing with contemporary cultural trends. The dynamic nature of gastronomy reflects its continuous adaptation to shifting technological and societal dynamics. Furthermore, it enhances the body of knowledge on gastronomy, emphasising its role in cultural identity, destination marketing, and tourism development (

Ren & Fusté-Forné, 2024;

Moreno Quispe & Hernández Rojas, 2025;

Stalmirska, 2024;

Park & Widyanta, 2022), as well as the significance of its preservation as intangible cultural heritage (

Ramazanova et al., 2022b).

This study also lays the groundwork for future research, particularly in examining tourists’ perceptions of local gastronomy and how new generations can continue to preserve and adapt this heritage.

In future research, we intend to include the opinions of tourists, restaurateurs, and representatives from the gastronomy sector, enriching the discussion and providing a broader and more diverse perspective. Tourists’ viewpoints can reveal how they perceive and value local cuisine. At the same time, the experiences and challenges faced by restaurateurs offer valuable insights into the sustainability and promotion of traditional dishes.

Furthermore, analysing public policies related to protecting gastronomy as cultural heritage is an essential aspect that deserves further investigation. Compared with other regions of Portugal or European countries with a strong gastronomic tradition, significant differences in approaches to preserving and promoting food culture can be revealed, offering valuable lessons that can be applied locally. In this context, we also aim to broaden the geographical scope of the analysis to include more rural areas, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of how traditional gastronomy is perceived and preserved in various regions.

Analysing the share of restaurants offering traditional dishes and their impact on tourism revenues can enhance our understanding of gastronomy’s economic significance. This would emphasise the value of local cuisine and serve as a foundation for strategies to promote gastronomy as a key tourist attraction.

Traditional Portuguese cuisine is not merely about food; it represents a vibrant heritage that connects the past with the present and nurtures a sense of national pride. By safeguarding this heritage, Portugal can ensure that its culinary traditions continue to thrive, using them to entice tourists seeking authentic cultural experiences. Integrating gastronomy into tourism strategies can bolster economic growth, support local communities and sustainability, and preserve the unique flavours that render Portugal a gastronomic treasure on the world stage.

Like any study, this research has its limitations. These limitations include the geographical area, which focuses only on part of Porto city, the characteristics of the respondents who participated in the study, including a predominance of respondents aged under 29, and the use of a convenient sampling approach, which introduces potential sampling bias that may affect the generalisability of the findings and the applicability of the results to broader populations. Thus, future work will consider all these aspects and use more robust sampling methods.