1. Introduction

Museums are among the most visited tourist attractions worldwide. The Louvre in Paris remains the world’s most visited museum, drawing over 8.9 million visitors in 2023 (

Louvre, 2024). Other major European museums also report significant annual attendance, including the British Museum in London (5.8 million visitors), the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid (3.3 million), and the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence (2.7 million) (

Statista, 2025). Museum attendance rebounded significantly since the COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting their lasting popularity. These numbers underscore the vital role of museums in global tourism, as they continue to attract millions of visitors and remain central to cultural travel experiences.

The steady annual influx of millions of visitors highlights the enduring significance of museums, not only as tourist destinations, but also as vital centers of cultural education. This raises critical questions about their sustainability—both as tourist destinations and as institutions responsible for fostering ethical, inclusive, and resilient engagement with social justice issues.

Zipsane (

2023) attributed the strong post-pandemic recovery in museum attendance to a renewed interest in museums as repositories of historical and cultural knowledge. Beyond offering opportunities to view iconic works of art and deepen historical understanding, museums serve as platforms for engaging with social justice issues, enabling visitors to gain broader insights into diverse cultures and histories (

Assylkhanova et al., 2025;

Landeta-Bejarano et al., 2025;

Pedroso et al., 2023;

Piras & Pedes, 2025). Consequently, how museums present social justice topics, particularly colonial histories, has become an increasingly important aspect of the visitor experience. This evolving engagement underscores the intersection of resilience and sustainability in museum practices. As museums respond to cultural shifts, they must balance historical preservation with the need to incorporate diverse voices into their narratives (

Boelhower, 2024;

Domínguez et al., 2024).

Museums traditionally engaged with social justice issues and recognized their responsibility to interpret and present the historical narratives of their collections to the public. However, these narratives often reflect a dominant Eurocentric perspective. Historically, many European museums framed their narratives around colonial legacies, emphasizing themes of wealth, conquest, and artifact acquisition (

S. Macdonald, 2003). Moreover, museums frequently function as institutions that reinforce Eurocentric narratives, prioritizing European superiority while marginalizing the histories of colonized populations (

Knell, 2014;

Sogbesan, 2022). Additionally, many museum artifacts possess problematic provenances that remain obscured or inadequately addressed for visitors (

Hicks, 2020). Even when museums attempt to acknowledge their colonial histories, exhibits often remain rooted in Western epistemologies, privileging Eurocentric interpretations over indigenous knowledge systems (

Malig Jedlicki & Oosterman, 2024). The persistence of these curatorial practices, even when well-intentioned, continues to marginalize the voices of the communities from which these objects were taken (

Diyabanza, 2020).

Recently, increasing recognition of the Eurocentric bias in museum narratives underscored how these institutions historically marginalized or silenced the voices of populations subjected to colonial rule. Contemporary museum visitors increasingly demand narratives that critically examine colonial histories and foreground the perspectives of marginalized communities (

Soares, 2018;

Soares & Leshchenko, 2022). This shift aligns with broader cultural movements seeking to confront the enduring legacies of colonialism, slavery, and systemic inequalities. In response, some museums attempted to address these concerns by supplementing traditional narratives with additional historical context and alternative perspectives (

B. Macdonald, 2022;

B. Macdonald & Parzen, 2023). However, integrating these perspectives into museum exhibitions remains an ongoing challenge, particularly in ensuring that such efforts are not merely symbolic, but lead to meaningful, sustained engagement with colonial histories. Achieving this balance requires museums to critically reassess curatorial practices to ensure historical accuracy, ethical responsibility, and long-term institutional commitment to decolonizing narratives.

A key strategy for addressing colonial legacies in museums is the integration of supplementary labels alongside traditional descriptions of exhibited art and artifacts. These additional labels provide alternative historical perspectives, situating artifacts within broader and often more complex colonial contexts. By displaying traditional and supplementary labels side by side, museums construct dual narratives that not only acknowledge the contributions and experiences of historically marginalized communities, but also directly challenge the dominant Eurocentric frameworks that traditionally shaped museum storytelling. This curatorial approach fosters a more critical and multidimensional engagement with artifacts, encouraging visitors to interrogate historical narratives and develop a deeper, more nuanced understanding of colonial histories (

B. Macdonald, 2022).

This study employs an interdisciplinary framework to examine how the inclusion of supplementary labels addressing colonial legacies influences the narratives and historical interpretations encountered by museum visitors. Specifically, this research investigates how a temporary exhibit featuring such labels introduced new historical perspectives, identities, and counter-narratives to visitors. Additionally, it explores the narrative void created when the exhibit ended and these labels were removed, thereby assessing the extent to which such interventions foster lasting critical engagement or risk becoming ephemeral gestures. By analyzing what is gained and lost through the addition and removal of these labels, this study offers critical insights into how museums can sustain their role as educational and cultural institutions for tourists while adapting their narratives to contemporary ethical and scholarly expectations. While existing research extensively examined decolonial curation and the ethics of artifact repatriation, fewer studies assessed the long-term impact of temporary interventions—such as supplementary museum labels—in reshaping visitor engagement with colonial histories (

B. Macdonald, 2022;

B. Macdonald & Parzen, 2023). This study addresses this gap by evaluating whether these temporary additions promote sustained critical engagement or contribute to moral licensing, where short-term efforts create a false sense of progress while ultimately reinforcing dominant narratives. Accordingly, this paper explores the following research questions:

RQ1: What new historical narratives and perspectives on colonialism did visitors encounter through the inclusion of supplementary museum labels addressing colonial legacies?

RQ2: What insights can be drawn from the addition and subsequent removal of these labels to inform future strategies for fostering sustained critical engagement with social justice issues, particularly colonial histories, in museum settings?

By examining these research questions, this paper contributes to ongoing discussions on how destination museums can critically and sustainably engage tourists with colonial legacies. While existing scholarship explored decolonial curation (

Boelhower, 2024;

B. Macdonald, 2022) and the ethics of artifact repatriation (

Domínguez et al., 2024), less attention has been devoted to the impact of short-term interventions, such as supplementary museum labels, on visitor engagement with colonial histories. This study addresses this gap by applying Gramsci’s theory of hegemony (

Bates, 1975) to examine how both original and supplementary museum labels construct and convey dominant and counter-hegemonic narratives. Additionally, the concept of moral licensing (

Merritt et al., 2010) provides a critical framework for analyzing how the removal of temporary curatorial efforts may unintentionally reinforce hegemonic perspectives, allowing institutions to revert to dominant narratives under the guise of prior progress.

This analysis situates the findings within broader discussions of destination resilience, underscoring the dual role of museums as both repositories of cultural heritage and adaptive institutions within heritage tourism (

Janes & Sandell, 2019;

Lonetree, 2012). While resilience in tourism is often framed in terms of economic sustainability and post-crisis recovery (

Chynoweth et al., 2020;

Redman, 2022), museums must also cultivate strategies that ensure continuous and meaningful engagement with social justice issues (

Message, 2014;

Smith, 2006). The temporary inclusion and subsequent removal of supplementary museum labels provide a lens through which to examine museums as sites of both historical reckoning and erasure, contingent upon their willingness to integrate marginalized voices into their permanent narratives. By critically assessing what is gained and lost in temporary exhibits, this study offers insights into how curatorial practices can be made more sustainable and ethically responsible when engaging with social justice issues.

2. Colonial Legacies and the Challenge of Destination Resilience

Many countries, particularly in Europe, continue to grapple with the complexities of their colonial legacies. Contemporary efforts to acknowledge and address this heritage vary significantly across regions, reflecting diverse political, cultural, and historical contexts (

Aldrich, 2009). One of the most visible forms of acknowledgment occurs through the display of colonial-era artifacts in museums, yet such exhibitions frequently raise ethical concerns regarding the historical contexts of acquisition and the curatorial choices shaping their presentation (

Small, 2011). As a discipline, museology involves constructing historical narratives through the selection and interpretation of artifacts. However, this process is often shaped by external sociopolitical forces, influencing the stories that museums ultimately convey (

Bergeron & Rivet, 2021). Historically, museums functioned as racialized institutions, reinforcing dominant power structures and privileging Eurocentric perspectives (

Ray, 2019). In

Decolonize Museums (2022), Shimrit Lee critically examined the origins of museums within the frameworks of colonial power and epistemic authority, arguing that their development was deeply intertwined with imperialist ideologies. Lee advocated for the dismantling and reframing of museum narratives, proposing a shift toward more equitable and inclusive storytelling that amplifies historically marginalized voices.

The themes explored in this study have been widely examined within anthropology but remain comparatively underexplored through a sociological lens, particularly in relation to tangible colonial legacies (

Harris & O’Hanlon, 2013).

von Oswald and Tinius (

2020) analyzed how nations and museum curators navigate the challenges of determining the “correct” approach to sensitive topics, including the legitimacy of artifact ownership, the histories of slavery, and persistent power dynamics. Their work underscores the complexities and ethical dilemmas inherent in addressing these issues within museum contexts. An anthropological study of the Mutare Museum in Zimbabwe found that acknowledging and incorporating colonial influences can enable museums to function as “community-anchoring institutions”, fostering constructive engagement with a difficult past (

Chipangura & Mataga, 2021). Similarly,

Mason and Santiago’s (

2023) research on Latin America’s historical ties to the Philippines highlights how interwoven colonial histories present significant challenges in shaping contemporary bilateral relationships. Various studies, such as those by

Thomas (

2009) and

Bancel et al. (

2017), explored postcolonial legacies across Europe, including detailed investigations into how countries such as France confronted their colonial histories. These studies collectively illustrate the diverse and context-specific strategies employed in addressing colonial pasts within museum narratives, highlighting the ongoing tensions between historical accountability, national identity, and cultural heritage management.

Recently, governments in countries such as the Netherlands have taken steps to formally acknowledge their colonial legacies (

Anderson & van den Berg, 2021). Although the Dutch government historically resisted policy initiatives addressing historical accountability (

McEachrane, 2021), recent actions signal a shift toward confronting and reassessing its colonial past. For instance, members of the Dutch monarchy publicly acknowledged the nation’s colonial history as part of broader efforts to promote historical reckoning and reconciliation (

Noor Haq & Krever, 2022). Similarly, Dutch museums revised their curatorial approaches to address growing critiques of the country’s colonial legacy, incorporating historically marginalized perspectives to foster a more inclusive representation of the past (

Ferrer, 2023;

Hickley, 2024). This study is grounded in the understanding that museums function not as static institutions but as dynamic cultural sites that must continuously adapt to evolving political, social, and scholarly discourses on colonial histories. Accordingly, this research examines how efforts to reframe colonial legacies shaped the presentation of art and artifacts, identifying key lessons that can inform sustainable and ethically responsible curatorial practices aimed at critically engaging with colonial histories.

Museums play a pivotal role in global tourism, attracting millions of visitors annually and serving as critical sites for both the presentation and contestation of historical narratives (

Redman, 2022). As cultural institutions, museums are responsible not only for preserving artifacts and historical records, but also for shaping public memory and engaging with evolving social and ethical discourses (

Lonetree, 2012;

Turner, 2020). Addressing destination resilience necessitates an examination of how tourist destination museums navigate the challenges of historical accountability and sustainability in their engagement with colonial legacies. While resilience in tourism is often framed in terms of a destination’s ability to recover from crises or disasters, it is equally essential to assess how museums adapt to shifting cultural expectations and demands for ethical representation (

Janes & Sandell, 2019). Resilience in heritage tourism encompasses both planned and adaptive strategies. Planned resilience involves deliberate curatorial efforts to integrate marginalized voices into exhibitions, ensuring that museum narratives reflect diverse historical perspectives (

Basyar et al., 2025;

Message, 2014). In contrast, adaptive resilience pertains to how museums respond to public discourse, critiques of traditional curatorial practices, and evolving debates on colonialism, social justice, and historical representation (

Smith, 2006). This study examines how the temporary inclusion of supplementary labels addressing colonial legacies functioned as an intervention into hegemonic narratives within a museum setting. While these labels expanded tourist engagement with the complexities of colonial histories, their subsequent removal underscores the precarious nature of such efforts, as they risk becoming temporary and performative rather than substantive and enduring (

Spiessens & Decroupet, 2023). Without sustained institutional commitment, museums risk falling into patterns of moral licensing, where temporary inclusivity measures serve to justify the continued dominance of traditional narratives without enacting meaningful structural change (

Merritt et al., 2010).

By analyzing the role of museums as central sites of heritage tourism, this research highlights the imperative for long-term strategies to ensure sustained engagement with social justice issues. The analysis identifies resilience at multiple levels. At the individual level, tourists engage with museum narratives in ways that shape their understanding of colonial histories and contemporary social justice concerns (

Brown, 2019). At the institutional level, museum curators, administrators, and destination management organizations influence how historical narratives are framed, which perspectives are included, and how exhibits evolve over time (

Janes & Sandell, 2019). As museums increasingly position themselves as spaces for historical dialogue and ethical engagement, this study underscores the critical need for sustained curatorial strategies that extend beyond short-term responses to public pressure. Destination resilience in tourism should not be limited to logistical or economic considerations, but must also encompass a museum’s capacity for continuous, critical engagement with historical accountability and social justice issues. By integrating marginalized voices into permanent exhibits rather than confining them to temporary or supplementary displays, museums can contribute to a more sustainable, accountable, and ethically engaged tourism industry (

Lonetree, 2012).

3. Theoretical Framework

Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony (

Gramsci & Boothman, 1995) provides a well-established framework for understanding how dominant groups (the hegemon) wield power to shape cultural and ideological narratives. Hegemony refers to the process by which a dominant class or group imposes its worldview on less powerful groups (the subaltern), thereby marginalizing or silencing alternative perspectives. This hegemon–subaltern dynamic is particularly relevant to museums, which function as cultural institutions with the authority to either reinforce or challenge historical narratives. Through the curation of artifacts, stories, and exhibits, museums possess the power to perpetuate hegemonic ideologies, thereby shaping public understandings of history and culture (

Bates, 1975). Gramsci identified subaltern groups as those systematically excluded from dominant narratives, including marginalized populations such as Indigenous communities and enslaved peoples. A defining characteristic of subaltern groups is their lack of agency or positionality in controlling how their histories are represented. This dynamic is particularly relevant in museum contexts, where dominant narratives historically glorified European colonial histories of conquest, wealth, and governance while silencing or omitting subaltern histories of violence, dispossession, and exploitation (

Molden, 2016).

Gramsci’s theory of hegemony offers a robust theoretical framework for analyzing museum exhibits and the narratives they present to visitors. It is particularly relevant to this research, which examines a temporary museum exhibit designed to address colonial legacies by introducing alternative perspectives and counter-narratives. Using Gramsci’s framework, this study systematically analyzed both original and supplementary museum labels within this exhibit to examine how traditional hegemonic narratives are contested and subaltern voices are elevated. By applying Gramsci’s theory of hegemony, this research employs content analysis of exhibit labels to critically assess the extent to which museum narratives reinforce or disrupt hegemonic structures.

In addition to Gramsci’s theory of hegemony, this study applies the theory of moral licensing as an interpretive tool to examine the unintended consequences of temporary museum interventions. This dual-theoretical framework informs both the coding and analysis of museum labels, enabling this research to assess not only how subaltern voices are introduced, but also how the removal of the exhibit reinforces hegemonic narratives. Moral licensing, a psychological concept introduced by

Merritt et al. (

2010) and further developed by

Mullen and Monin (

2016), describes how individuals and institutions may feel justified in acting less ethically after performing a prior moral action. This "license" effect occurs because previous moral acts create a psychological buffer, fostering a perception of integrity while simultaneously reducing guilt.

In the context of colonial histories and museum narratives, moral licensing provides insight into how the temporary acknowledgment of subaltern voices—such as those highlighted in new museum labels—can inadvertently enable institutions to revert to hegemonic perspectives. Because the exhibit was temporary, its critiques of colonialism and the amplification of marginalized voices may have only briefly disrupted hegemonic narratives. Once the exhibit ended and the labels were removed, the museum risked treating the intervention as sufficient, allowing it to reaffirm dominant colonial themes and perspectives. In this way, moral licensing explains how short-term inclusionary efforts can inadvertently undermine long-term structural reforms aimed at sustaining critical engagement with colonial legacies. Institutions may perceive temporary engagement with social justice issues as a meaningful step forward, yet without the permanent integration of marginalized perspectives, such efforts remain symbolic gestures rather than catalysts for systemic change. By using moral licensing as an analytical tool, this study underscores the need to ensure that museum interventions intended to facilitate sustainable change do not become justifications for the continued presentation of hegemonic frameworks under the guise of progress. By applying Gramsci’s theory of hegemony and the concept of moral licensing, this study addresses a key research gap: whether temporary interventions in museum curation produce sustained critical engagement or inadvertently reinforce dominant narratives by functioning as symbolic, short-lived gestures.

4. Materials and Methods

Guided by theories of hegemony and moral licensing, this study employs content analysis to systematically examine how a temporary exhibit on colonial legacies shaped visitors’ understanding of hegemonic and subaltern narratives. The data for this analysis are drawn from a temporary exhibit on colonial legacies at a prominent European museum (

Statista, 2025), which ran from 2021 to 2024. Acknowledging that many of its artifacts and historical collections were deeply entangled with state-sanctioned systems of slavery and exploitation, the museum sought to present a more comprehensive and critical account of its complex colonial past. Under colonial rule, enslaved individuals worldwide were systematically stripped of their freedom, possessions, and the ability to document their lives, leaving their histories erased or unheard for centuries. To address this legacy of silencing, the museum introduced 77 supplementary labels as part of an exhibit focusing on colonial legacies and slavery. These labels were designed to critique colonial systems, amplify marginalized voices, and construct a more nuanced and inclusive historical narrative. The museum’s intervention was structured around three core themes: (1) critiquing colonial legacies, (2) recognizing the lived experiences of historically marginalized groups, and (3) offering visitors a broader, more comprehensive understanding of its historical context.

This study employs content analysis, a well-established method for examining textual materials, to analyze the texts displayed on both the original and supplementary museum labels. The objective is to assess how these exhibits shape visitors’ understanding of the museum’s colonial legacies. Content analysis is particularly well-suited for systematically evaluating the narratives and messages conveyed through textual materials, making it an effective approach for exploring how museum labels construct and communicate historical interpretations.

This analysis was guided by the thematic goals outlined in the exhibit’s mission statement. Specifically, the following themes were examined: (1) critique of colonial legacies, (2) recognition of marginalized voices, and (3) presentation of a more comprehensive historical narrative. Each theme was associated with a set of keywords derived from an extensive review of relevant literature, the museum’s interpretive objectives, and a pilot analysis of a subset of labels. For example, keywords associated with critiquing colonial legacies included terms such as “appropriated”, “victim”, “enslaved”, and “exploited”.

The data collection process involved transcribing the content of both the original and supplementary museum labels (154 total labels) into a textual database. Each label was then systematically coded using predefined keywords associated with the exhibit’s themes. The presence of these keywords was flagged as evidence of their corresponding themes. Given the exhibit’s 154 labels, word frequency analysis was conducted to highlight the major themes and experiences tourists encounter in the museum. A lower word count for a term indicates that tourists are less likely to engage with that topic, whereas higher word counts increase the probability of tourist engagement and sustained interaction with that concept. Additionally, this analysis illustrates how the overall narrative shifts with the addition and removal of museum labels. Beyond quantifying occurrences, qualitative analysis was conducted to assess the depth of engagement with each theme. This ensured that the text aligned with hegemonic and subaltern ideas in a meaningful way. For instance, instances categorized under recognition of marginalized voices were further analyzed to determine whether they provided substantive insights into lived experiences or merely functioned as tokenistic acknowledgments.

To enhance objectivity, multiple team members independently coded the museum labels using a systematic content analysis approach. This process involved identifying recurring themes, concepts, and keywords within the labels that were relevant to the research objectives. Keywords were selected based on their frequency, relevance to the study’s core themes, and ability to encapsulate the main ideas expressed in the museum labels. Each team member was assigned a subset of labels and applied a predefined coding scheme to categorize the content. After the initial coding phase, triangulation was conducted by comparing and contrasting the codes assigned by each team member. This triangulation process ensured coding consistency and minimized bias. To validate the content analysis, inter-coder reliability checks were performed, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. This rigorous process enhanced the robustness and accuracy of the findings.

Below, word counts for key terms found in both the original and supplementary museum labels are presented to illustrate the frequency and range of terms. Additionally, separate word clouds were generated to visualize the central messages and themes encountered by tourists in the museum. These visualizations further highlight the thematic differences between the original and new museum labels. This study adopts a robust and systematic approach to examining hegemonic and subaltern narratives curated and conveyed within museum settings. By comparing and contrasting the original and supplementary museum labels, this research demonstrates how the inclusion and subsequent removal of supplementary materials impact representation gaps related to colonial legacies.

5. Results

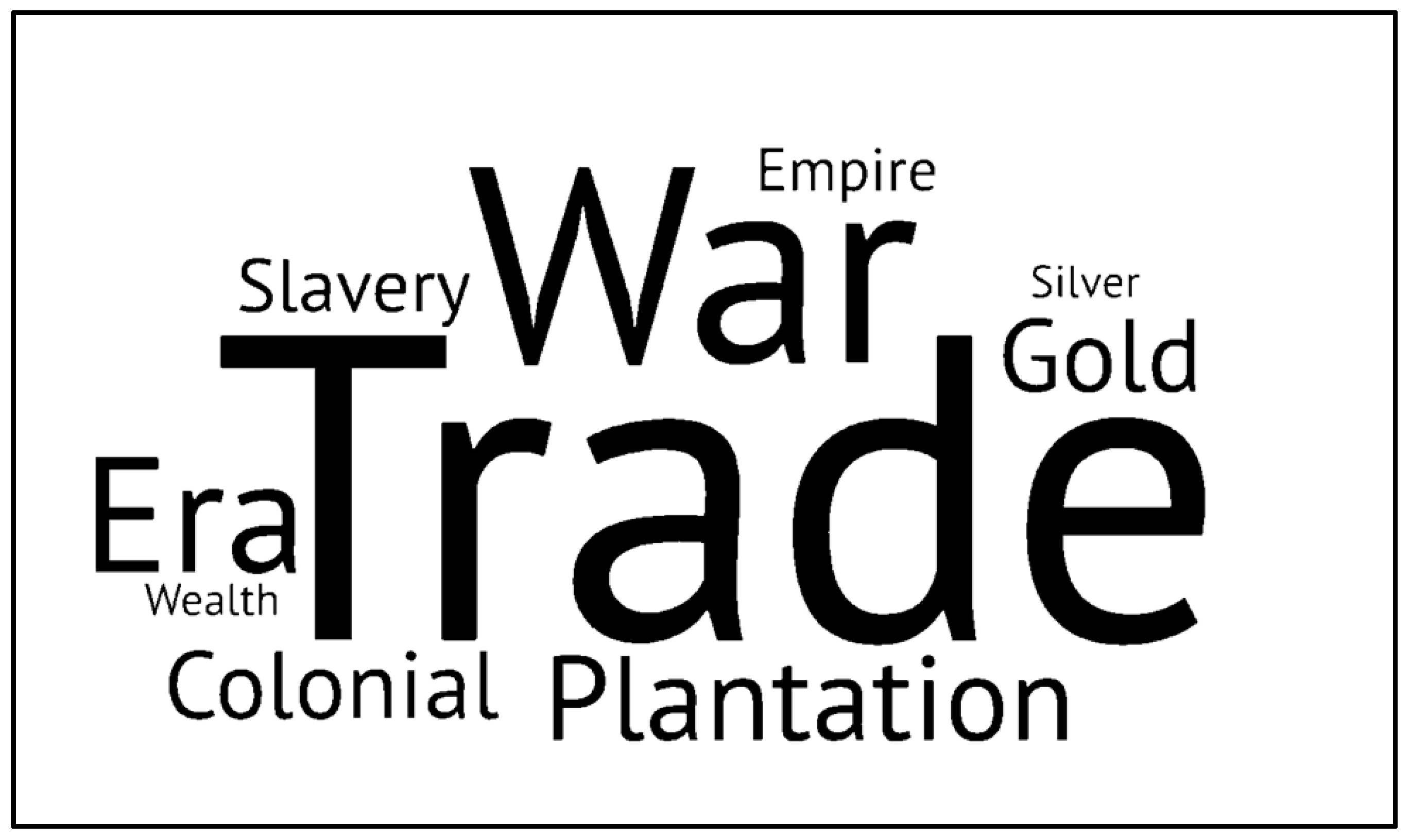

5.1. Critique of Colonial Legacies

The most prominent theme identified in the content analysis—and central to the exhibit’s mission—is the critique of colonial legacies. A total of 218 new keywords addressing colonial legacies were introduced in the supplementary museum labels, marking a substantial expansion of the critique of hegemonic colonial narratives. This expansion incorporates topics and perspectives that were marginalized or entirely absent in the original labels. This shift is reflected in the increased frequency and depth of terms associated with colonial exploitation and the experiences of subaltern groups, as demonstrated by the word counts. For instance, the term

enslaved appears nearly five times more often in the supplementary labels (95 mentions compared to 20), indicating a more comprehensive engagement with the realities of slavery and forced labor (

Figure 1). The supplementary labels also introduce new terms and concepts that were absent from the original labels, such as

appropriated,

exploited, and

racism. These additions reflect an intentional effort to challenge hegemonic narratives and amplify subaltern voices. Thematic shifts become more evident when comparing the word clouds generated from the original and supplementary labels (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). As a well-established tool, word clouds effectively highlight changes in dominant themes and user experiences, making changes in complex patterns easier to identify and interpret (

DePaolo & Wilkinson, 2014). While

enslaved remains the most frequently occurring term in both sets of labels, the supplementary labels emphasize additional terms that provide a more pointed critique of traditional colonial narratives. This shift reframes the visitor experience: rather than a narrative in which

trade,

power, and

wealth dominate representations of colonialism, the supplementary labels foreground

exploitation,

resistance, and

slavery as central themes.

This thematic transformation aligns with Gramsci’s theory of hegemony, which explains how dominant groups consolidate power by constructing narratives that legitimize their authority while marginalizing subaltern voices. The supplementary labels serve as a counter-hegemonic intervention, amplifying subaltern perspectives by foregrounding the experiences of enslaved individuals, Indigenous resistance, and the appropriation of resources. Terms such as exploited (eight mentions), appropriated (five mentions), and victim (five mentions) underscore the systemic dehumanization of colonized populations and the economic advantages accrued by European powers through resource extraction and forced labor. The museum’s critique of colonialism fulfills one of the exhibit’s core objectives—constructing a more comprehensive historical narrative. This revised narrative explicitly connects European economic prosperity (wealth, eight mentions) and trade (21 mentions) to the structural oppression and exploitation of colonized groups. By establishing these historical linkages, the exhibit disrupts hegemonic narratives that glorify trade and expansion, instead foregrounding the human costs of colonialism. This approach not only challenges conventional narratives, but also repositions subaltern perspectives at the center of historical interpretation, fostering a deeper and more critical engagement with colonial histories.

The addition of the supplementary museum labels significantly enhances the critique of colonial exploitation and amplifies subaltern voices. This expanded discussion aligns with the museum’s stated goals and represents a critical step toward acknowledging and addressing the enduring legacies of colonialism.

5.2. Increased Recognition of Marginalized Voices

The next theme examined is the enhancement of marginalized voices through the addition of supplementary museum labels. These labels significantly increase the representation of subaltern perspectives, with terms such as

slave and

enslave appearing at notably higher frequencies. The introduction of new terms such as

appropriated and

exploited reflects a deliberate shift toward acknowledging the lived experiences of those who endured the brutalities of colonial rule. This shift elevates previously silenced voices, integrating them more prominently into the museum’s historical narrative (

Figure 4). Additionally, while the use of power decreases in the new labels, there is a stronger focus on the lived realities of individuals subjected to colonial rule. This reframing disrupts the hegemonic narrative that glorifies colonial dominance and instead amplifies marginalized perspectives, providing visitors with a more critical and comprehensive engagement with the museum’s colonial legacies (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

Furthermore, the inclusion of these new terms enables the museum to take substantive steps toward addressing historical silences that become evident when only the original museum labels are considered. By doing so, the exhibit restores agency to those who were historically oppressed, aligning with Gramsci’s call to elevate subaltern voices. This demonstrates how museums can serve as critical spaces for confronting and reinterpreting colonial legacies. A striking example of this shift in recognition emerges in Portrait 20, which depicts a wealthy colonial leader with an enslaved man positioned behind him. The original museum label focuses exclusively on the colonial leader’s accomplishments in Africa, describing the scene as follows: “The gold and the African man symbolize merchandise traded on the Gold Coast”. In this account, the enslaved man is stripped of his humanity, reduced to an object of trade equated with gold within the colonial economy. In contrast, the new museum label offers a fundamentally different perspective, providing visitors with deeper insight into the life and experiences of the enslaved man. The revised label states:

The young man … is one of the many people enslaved… African traders took him and other prisoners to trading posts to be sold…. A total of 550,000 Africans to the Americas and the Caribbean. As slaves they were dehumanized: they were taken far away from their place of birth, separated from their families and friends, branded, and denied any say over their own actions and bodies.

This example demonstrates how the new museum labels directly challenge the hegemonic narrative of colonialism. The additional text provides visitors with a clearer understanding of how the colonial leader’s success was built on the exploitation and enslavement of others. Moreover, the revised description reshapes the narrative by centering the humanity of the enslaved man rather than reducing him to a mere commodity.

Unlike the original museum label, which emphasizes the wealth generated by colonialism and depicts enslaved individuals as passive elements within a trade system, the new label restores agency to the enslaved African. It highlights the profound trauma of being forcibly removed from his homeland, separated from loved ones, and dehumanized through branding. By amplifying this perspective, the label ensures that the lived realities of marginalized, or subaltern, individuals are recognized as fundamental to the historical narrative, fostering a more critical and inclusive engagement with colonial history.

5.3. Presentation of a More Comprehensive Historical Narrative

The content analysis of how the museum constructs a more comprehensive historical narrative reveals that the new museum labels contain a higher word count and incorporate a broader range of key terms (

Figure 7). In both the original and revised labels,

trade emerges as the most frequently used term when addressing historical narratives, reflecting the museum’s colonial history. However, the new labels provide greater context, emphasizing how the wealth derived from trade was largely built on

slavery (30 mentions) and how enslaved individuals labored on

plantations and in

colonies (both 17 mentions). By comparing the word clouds generated from these key terms (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), it becomes evident that trade remains central to the historical narratives. The revised labels also introduce a more critical perspective by amplifying subaltern voices and integrating repeated references to

resistance,

Indigenous, and

exploitation. This shift challenges the traditional narrative, reframing trade as a system inseparable from oppression and forced labor. Without the supplementary labels, the narrative remains dominated by a Eurocentric perspective that portrays conquest, wealth accumulation, and imperial expansion as symbols of progress, while marginalizing the voices of those who bore the costs of these conquests. This aspect aligns with Gramsci’s theory of hegemony, wherein dominant groups—in this case, European voices—assert control not only through economic power, but also by shaping historical narratives that justify their actions. The original museum labels often reinforce this dominance by glorifying empire and colonial rule while failing to acknowledge the exploitation that sustained them. In contrast, the new museum labels actively confront these omissions, providing visitors with a more historically responsible and critically engaged interpretation of colonial legacies.

The content analysis reveals that one of the most significant contributions of the new museum labels is the inclusion of a more complex historical narrative that integrates subaltern voices. The revised labels introduce 23 additional accounts that expand upon the historical legacies addressed in the original labels, offering visitors new perspectives on the experiences of enslaved peoples, colonial exploitation, and resistance movements. By elevating subaltern voices, the new labels disrupt the hegemonic narrative and challenge the glorification of colonial achievements. These additions complicate and enrich the historical account presented to visitors, fostering critical engagement with the museum’s portrayal of colonial history. By incorporating subaltern perspectives, the revised labels encourage visitors to interrogate the dominant narratives found in the original labels and cultivate a deeper, more inclusive understanding of the past.

An example of how the new museum labels construct a more comprehensive historical narrative is evident in the labels accompanying Paintings 3 and 4, which depict portraits of a wealthy merchant husband and wife. The original labels present the couple as esteemed members of elite society, emphasizing their sumptuous clothing adorned with expensive embellishments. Their wealth is attributed to a successful sugar refinery, portraying them as affluent and accomplished. The revised labels challenge this portrayal by providing visitors with a deeper understanding of the origins of their wealth. These labels reveal that the couple’s fortune was built on a sugar plantation in South America, where sugar was cultivated, harvested, and processed by Africans who had been enslaved. By exposing the reliance on slave labor that sustained their lifestyle, the revised labels shift the narrative from an uncritical celebration of wealth to a more nuanced account that foregrounds the exploitative and inhumane practices that enabled their prosperity.

Gramsci’s concept of hegemony provides critical insight into the significance of this shift in the portrayal of colonial legacy. The original museum labels reinforce hegemonic power by omitting the exploitative origins of the couple’s wealth, thereby legitimizing colonial achievements and obscuring the systemic oppression that enabled their affluence. In contrast, the revised labels disrupt this narrative by exposing the forced labor and exploitation that underpinned their prosperity, prompting visitors to engage with these portraits through a more critical and informed lens. By integrating subaltern voices, the revised labels not only expand the historical narratives associated with these artworks, but also reshape how visitors interpret similar pieces throughout the museum. Presenting information from both the original and new labels invites visitors to critically examine the histories embedded in the exhibits, fostering a deeper and more reflective engagement with the artifacts on display.

6. Discussion

6.1. What Lessons Can Be Learned?

This study highlights the challenge of ensuring that temporary museum interventions result in lasting shifts in public engagement with colonial histories. Addressing the research gap on the sustainability of such initiatives, the findings suggest that without institutional commitment, temporary efforts risk reinforcing rather than dismantling hegemonic narratives. While the introduction of the new museum labels provided a more comprehensive and critical account of colonial legacies, their long-term impact depends on sustained curatorial strategies. For museums seeking to adopt this model, this study offers four key recommendations for improvement.

First, the revised museum labels effectively exposed the economic and exploitative roles of enslaved individuals within the colonial system, demonstrating how colonial elites amassed wealth through their forced labor. However, while these labels surfaced hidden histories, they often presented enslaved individuals in a commodified and homogenized manner, emphasizing their economic function within the colonial apparatus rather than their lived experiences. This finding directly relates to the first research question (RQ1), as it reveals that while visitors encountered new narratives about colonialism, these narratives remained constrained in scope. Many revised labels documented the exploitation of enslaved labor for economic gain but provided limited insight into the personal histories, identities, and cultural agency of those who endured enslavement. To address this limitation, museums should integrate narratives that humanize enslaved individuals by centering their resilience, agency, and lived experiences. Expanding beyond depictions of economic exploitation to include personal histories would encourage visitors to view enslaved populations not solely as forced laborers, but as individuals with complex identities, emotions, and cultural contributions.

The exhibit provides limited insight into the experiences of women, particularly those from subaltern groups. This omission likely stems from the scarcity of historical documentation that captures the female experience under colonialism. As a result, male figures and narratives dominate as the hegemonic voice of this period, leaving women’s perspectives significantly underrepresented. Expanding narratives to include these perspectives would enrich the range of new stories that visitors encounter in museum exhibits (RQ1). Although elevating women’s voices from the colonial era presents challenges, their inclusion remains essential (

Molden, 2016). Actively seeking opportunities to incorporate these experiences would allow museums to present a more diverse and comprehensive account of colonial history.

Not all artwork or artifacts in the museum were accompanied by new labels with supplementary information. While it may not be practical to provide revised labels for every piece in the collection, offering transparency regarding the selection process would enhance visitor comprehension. For instance, some paintings included additional information addressing the colonial legacies of the subjects portrayed, while similar paintings in the same gallery did not. Without an explanation, visitors may leave with a fragmented or inconsistent understanding of the history presented in the exhibit (

Lonetree, 2012). Clarifying the criteria used to determine which artifacts received new labels would help ensure a more coherent and informed engagement with the exhibit’s themes.

Additionally, both the original and new museum labels are printed in colonial languages, requiring visitors from former colonies to engage with artifacts and narratives through former colonial and hegemonic linguistic frameworks. This limitation suggests that future strategies for engaging tourists with colonial histories (RQ2) should include multilingual accessibility. While standard in many museums, this practice reinforces the subaltern status of Indigenous languages and may alienate visitors from formerly colonized regions (

Lonetree, 2012;

Turner, 2020). When meaningful and contextually appropriate, the museum could consider incorporating labels in Indigenous languages alongside colonial ones. This approach would demonstrate respect for the cultures and languages of formerly colonized regions while providing visitors with additional opportunities to critically engage with the hegemonic colonial narratives presented in museums.

6.2. Removal of New Museum Labels and Moral Licensing

Although the addition of new museum labels significantly enhanced visitor engagement with the complex legacies of colonialism, the exhibit was temporary. As of early 2024, the revised labels were removed, meaning future visitors will no longer have access to the additional text and materials that elevated subaltern voices and challenged hegemonic perspectives. This directly relates to the second research question (RQ2), as it raises concerns about the sustainability of temporary interventions in shaping visitor engagement with colonial histories. The removal of these labels undermines the progress made in addressing social justice issues such as colonial legacies, particularly when viewed through the lens of moral licensing.

By temporarily showcasing subaltern and marginalized voices, the theory of moral licensing suggests that some may perceive their obligation to confront colonial histories as fulfilled (

Merritt et al., 2010). Even a brief elevation of subaltern voices may create an illusion of progress while justifying a return to the Eurocentric narratives presented in the original—and now sole—museum labels. This reversion reinforces the dominance of traditional hegemonic accounts of colonial history, allowing institutions to maintain their emphasis on narratives that prioritize colonial achievements. Without the new museum labels, the critical perspectives on colonial legacies risk being erased.

Moral licensing may also diminish the perceived urgency for sustained institutional change and engagement with social justice issues (

Mullen & Monin, 2016). When new voices have been briefly acknowledged, temporary interventions might be seen as sufficient, thereby impeding efforts for deeper and more enduring inclusion of subaltern narratives. Additionally, tourists may perceive that museums adequately addressed their colonial legacies, making them less inclined to demand exhibits that present a broader range of perspectives. If both institutional decision-makers and visitors regard the temporary exhibit as a complete effort toward historical accountability, the narratives and voices introduced through the new museum labels are unlikely to result in lasting or meaningful shifts in the museum’s engagement with colonial histories.

6.3. Sustainable and Practical Strategies for Museums

To move beyond temporary interventions and establish a sustainable engagement with social justice issues, museums must implement long-term, institutionalized strategies. Without embedding these efforts into core operations, museums risk reinforcing dominant narratives and allowing temporary initiatives to function as moral licensing rather than meaningful progress (

Merritt et al., 2010). A sustained commitment to ethical storytelling and historical accountability requires integrating inclusive practices into all aspects of museum curation and interpretation.

A key step is the permanent inclusion of subaltern voices in core exhibits rather than relegating them to temporary displays. Museums should systematically revise exhibit labels, expand collections to include artifacts representing diverse histories, and redesign permanent installations to ensure marginalized perspectives remain central (

Boelhower, 2024). This strategy directly addresses RQ2 by identifying ways to sustain critical engagement with colonial histories beyond temporary measures. By challenging Eurocentric narratives, this approach reinforces the museum’s role as an institution that documents history comprehensively rather than selectively curating it to maintain hegemonic perspectives (

Lonetree, 2012).

Another key strategy is rotational and adaptive labeling, which enables museums to update exhibit content without erasing critical perspectives. Rather than treating supplementary labels as temporary interventions, museums could implement a cycle of rotating interpretive materials that evolve in response to new research, public discourse, and community input (

Janes & Sandell, 2019). This approach not only sustains visitor engagement, but also aligns with broader efforts in heritage tourism resilience, where institutions must continuously adapt to shifting cultural expectations (

Smith, 2006).

Sustained engagement also requires collaboration with affected communities to ensure ethical representation of colonial histories. Museums should actively engage with Indigenous groups, descendants of enslaved populations, and scholars from formerly colonized regions to co-create exhibits rather than relying solely on institutional narratives (

Chipangura & Mataga, 2021). Establishing advisory panels, featuring guest curators, and integrating firsthand accounts from historically marginalized communities are practical steps that ensure these perspectives remain central to museum storytelling (

Domínguez et al., 2024).

Additionally, digital archives and augmented reality offer a sustainable approach to extending the impact of exhibits beyond physical spaces. Museums can develop digital repositories that preserve removed labels, oral histories, and interactive content, ensuring that critical narratives remain accessible even after temporary exhibits conclude (

Message, 2014;

Redman, 2022). QR codes linking to expanded historical narratives, virtual reality reconstructions, and interactive online exhibits can further enhance accessibility and engagement, transforming inclusive storytelling into a permanent institutional practice rather than a temporary initiative.

Equally crucial to sustaining long-term commitments to decolonial museum practices are staff training and institutional policy reforms. Museums should establish ongoing training programs for curators, educators, and administrators to ensure a continuous focus on ethical curation and inclusive storytelling (

Hickley, 2024). Additionally, policies should require the inclusion of marginalized perspectives in all major exhibits, preventing curatorial approaches from reverting to dominant colonial narratives (

Lee, 2022;

McEachrane, 2021). By integrating these changes into institutional frameworks, museums can transition from short-term, reactive measures to a sustained model of cultural accountability and historical integrity. These structural reforms directly address RQ2, ensuring that engagement with colonial histories extends beyond isolated interventions and becomes an enduring feature of museum practice.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights, its scope is inherently limited as a single case study of a temporary exhibit. Future research should systematically examine how different destination museums engage with social justice issues, particularly in institutions that may be less receptive to discussions on colonial legacies. While some museums actively incorporate these histories, others may face institutional or political constraints that hinder the implementation of similar interventions. A broader comparative analysis across national, regional, and private museums could reveal how structural factors influence engagement with colonial histories. Expanding research across diverse museum contexts would provide deeper insight into the broader applicability of these findings and offer guidance on fostering meaningful, long-term engagement with social justice issues. This study serves as a roadmap for museums, advocating for sustained cultural accountability and ongoing reassessment. Further investigation into best practices for addressing social justice issues in destination museums can help scholars and practitioners develop more effective strategies to ensure that engagement with colonial legacies remains sustainable, impactful, and responsive to the needs of diverse museum audiences.

7. Conclusions

Destination museums will continue to grapple with the complexities of addressing social justice issues and curating colonial narratives for visitors. The question of how museums and other tourist destinations can sustain meaningful engagement with social and cultural issues remains a pressing concern. This study underscores how even modest yet deliberate modifications to exhibits can disrupt hegemonic colonial narratives and amplify subaltern voices. These interventions offer visitors a more critical and inclusive understanding of colonial histories, fostering deeper engagement with the ethical dimensions of historical interpretation. By providing more transparent insights into the origins of artifacts and centering the lived experiences of those subjected to colonial systems, museums can facilitate a richer and more reflective engagement with the lasting impacts of colonialism. Embedding these narratives into permanent museum practices ensures that the inclusion of marginalized voices is not reduced to a symbolic or temporary gesture but becomes a foundational aspect of ethical curation, historical accountability, and responsible knowledge preservation.

However, if these efforts remain temporary, they risk failing to produce lasting change. The removal of the new museum labels deprives future visitors of transformative insights, allowing predominantly Eurocentric narratives to persist while marginalizing the lived experiences of those impacted by colonial rule. When exhibits are temporary, tourists lose access to critical narratives, reinforcing the need for sustainability efforts that extend beyond the physical preservation of artifacts. True sustainability must also encompass the continuous integration of marginalized voices and historical perspectives, ensuring that museums remain spaces of critical engagement rather than sites of selective storytelling.

The theory of moral licensing cautions that even well-intentioned but temporary efforts to challenge hegemonic perspectives may ultimately hinder lasting change by fostering a false sense of progress. To move beyond symbolic gestures, museums must balance short-term interventions with long-term strategies that embed marginalized voices into the permanent narratives of their exhibits. This research advances discussions on decolonizing museums by addressing a critical gap: whether temporary interventions, such as supplementary labels, lead to sustained change. The findings suggest that while these efforts can momentarily shift narratives, without the permanent integration of marginalized perspectives, museums risk engaging in moral licensing—appearing progressive while maintaining dominant colonial frameworks. By adopting resilient strategies that prioritize historical inclusivity, museums can serve as both dynamic tourist destinations and sustainable centers for cultural education and ethical engagement.