1. Introduction

Academia stands at the crossroads of teaching and research, traditionally regarded as its two main missions (

Bortagaray, 2009). Furthermore, universities bear a moral obligation to advance science and society by facilitating effective communication and fostering social engagement among their students (

Etzkowitz, 2003;

Rothaermel et al., 2007;

Di Berardino & Corsi, 2018). Consequently, universities are expected to undertake a vast range of activities, including promoting innovation and knowledge transfer, lifelong learning and continuing education, and contributing to social and cultural development (

Mora et al., 2015). At the same time, they must address these challenges while demonstrating accountability and an efficient use of public resources, a goal achievable only through meticulous strategic management (

Callagher et al., 2015;

Benneworth et al., 2016;

Aragonés-Beltrán et al., 2017;

De La Torre et al., 2017;

Mariani et al., 2018). Thus, universities serve a central role in cultivating desirable attributes (

Hirst & Peters, 1972), underscoring the necessity for them to be institutions of high quality.

Quality, however, is a complex and contentious concept to define, comparable to other abstract notions such as “equality” or “justice” (

Harvey & Green, 1993). Gibson emphasizes this by stating that delivering quality is just as difficult as it is to describe it (

Gibson, 1986). There is a wide range of different conceptualizations of quality being used (

Schuller, 1991) as its interpretation depends on the user and the specific context in which it is applied (

Harvey & Green, 1993). In the context of higher education, there are several stakeholders involved, including students, teachers, administrative stuff, government entities, and funding organizations (

Burrows & Harvey, 1992), where each of them has its own perspective and approach regarding quality, shaped by its distinct objectives (

Fuller, 1986;

Hughes, 1988). Even though there is no consensus among the various definitions, there is notable agreement on certain aspects (

Ball, 2008). These aspects of education quality include the inputs (e.g., students) and outputs (e.g., educational outcomes) of the education system, as well as its capability to satisfy needs and demands by meeting expectations (

Cheng, 1995).

Crosby (

1979) succinctly defines quality as “conformance to requirements”. It is worth noting that Coxe’s research (

Coxe, 1990) led to a positive correlation between citizens’ standards of living and education and their demand on the quality of products and services provided. In order to meet stakeholders’ expectations—considered the primary purpose of any product or service (

Feigenbaum, 1991;

Ismail et al., 2009)—there is a need for constant feedback (

Nur-E-Alam Siddique et al., 2013), making assessment essential. In the context of education, Bramley defines assessment as a process that aims to determine the value of a certain aspect of education, or education as a whole, to facilitate decision-making (

Bramley, 2003). This is achieved through a set of indicators designed to measure these values (

Diamond & Adam, 2000), which are then compared with predetermined objectives (

Noyé & Piveteau, 2018). Assessment can also be described as a process that captures the overall impression of an educational institution for the purpose of fostering improvement (

Vlasceanu et al., 2004). Therefore, assessment is widely regarded as the most effective mechanism to enact change within an educational institution, enabling its development and contributing to its success (

Darling-Hammond, 1994).

2. Literature Review

The absence of proper instruments to measure quality hinders the effort to improve it (

Farrell et al., 1991). Moreover, accurate quality measurements are required in order to assess a service change, via a before and after comparison (

Brysland & Curry, 2001). In the pursuit of assessing service quality,

Gronroos (

1982) developed a model based on the notion that consumers evaluate quality by comparing the service they expected with their perception of the service received. This line of thinking was followed by many researchers. For instance,

Smith and Houston (

1983) argued that consumer satisfaction depends on whether their expectations are met, while

Lewis and Booms (

1983) defined service quality as the extent to which the delivered service aligns with customer expectations. Recognizing that quality encompasses more than outcomes, researchers have explored appropriate dimensions of quality (

Parasuraman et al., 1985). For example,

Sasser et al. (

1978) proposed three dimensions of service performance: personnel, facilities, and levels of material. To enable their search for these dimensions,

Parasuraman et al. (

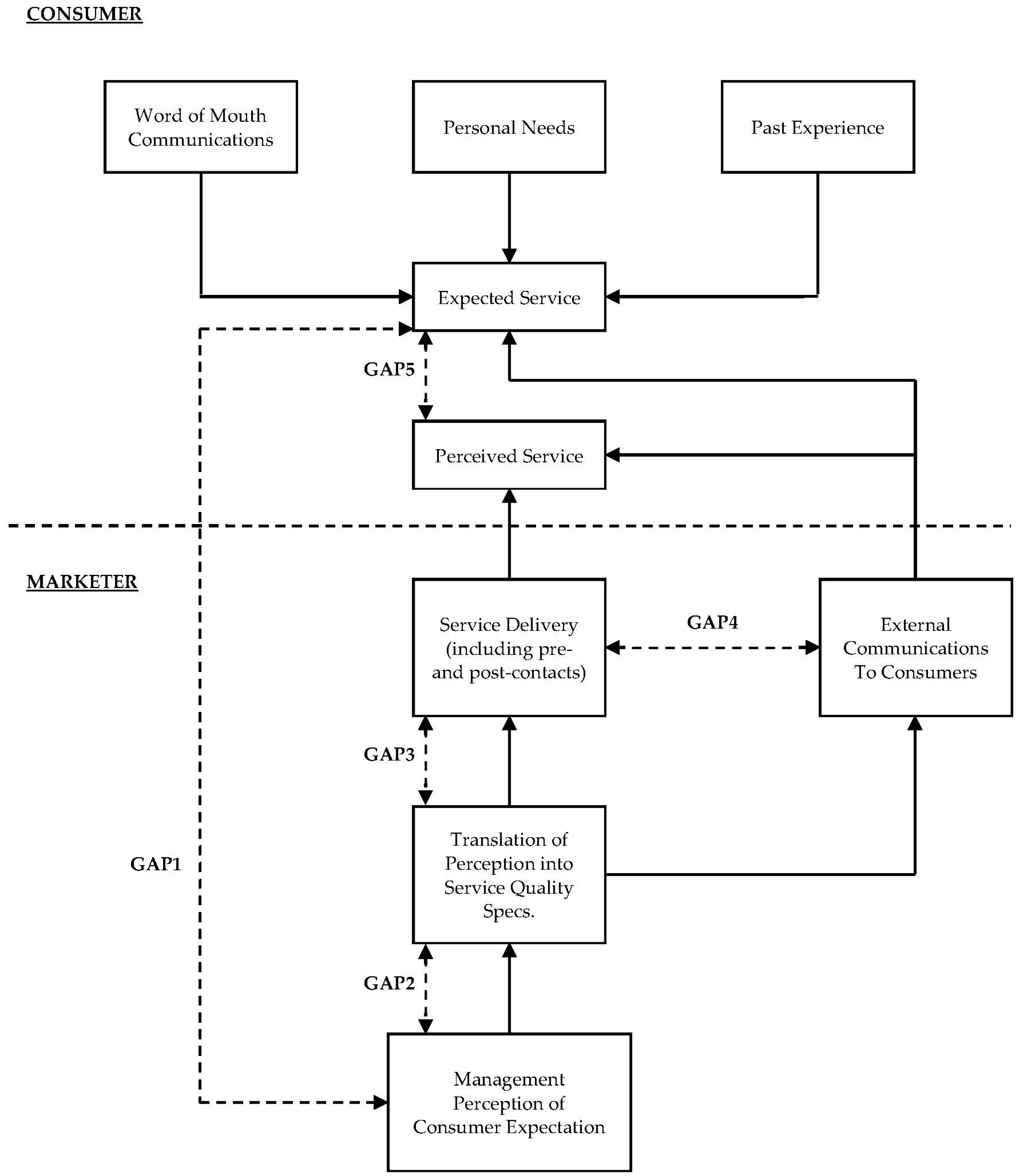

1988) investigated and proposed a framework that deconstructs the gap between expectation and perception into five distinct gaps (

Figure 1). The first gap arises from the difference between customer expectations and management’s perceptions of those expectations. The second occurs between management’s perceptions of customer expectations and the service quality specifications set by the firm. The third reflects discrepancies between the specified quality standards and the service actually delivered. The fourth emerges between the actual service delivery and how said service is communicated to consumers. Finally, the fifth gap is created between the actual service delivery, combined with how it is communicated, and the customers’ perception of said service, closing the loop between expectation and perception (

Parasuraman et al., 1985).

This investigation identified 10 key criteria categories—referred to as the sought-after dimensions—which, after further research and refinement, were consolidated into 5: tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy. Tangibles refer to facilities, equipment, and personnel appearance. Reliability concerns the ability to deliver the promised service accurately. Responsiveness reflects the willingness to assist customers and provide prompt service. Assurance pertains to personnel expertise and their ability to inspire trust. Finally, empathy involves the provision of individualized care to customers. This body of work culminated in the development of a service quality model known as SERVQUAL, which follows the above five-dimensional structure. The model is designed to capture the perception of service performance, along with its expectation (

Parasuraman et al., 1988). If perception falls below expectation, the service is deemed to provide low satisfaction. If perception matches expectation, the service is considered to provide adequate satisfaction. Finally, if perception exceeds expectation, the service is deemed to provide remarkable satisfaction (

Parasuraman et al., 1988).

In our study we introduced and utilized a modified version of the SERVQUAL quality measurement instrument to capture the Department of Tourism Management (University of Patras, Greece) students’ perceptions and expectations regarding the services provided by the departmental administrative offices and to potentially detect areas of service that may require improvement or redesign. The proposed modification lies in replacing traditional Likert scales with continuous scales, capturing the variance between the assessment’s underestimation and overestimation, enhancing the instrument by yielding more comprehensive insights. While SERVQUAL has been widely applied to assess service quality, most studies rely on fixed-point scales such as Likert scales, which are not capable of capturing the variance in respondents’ evaluations. This novel approach addresses this gap in the existing literature, while also contributing to the broader body of research on administrative quality assessment in higher education.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Participants

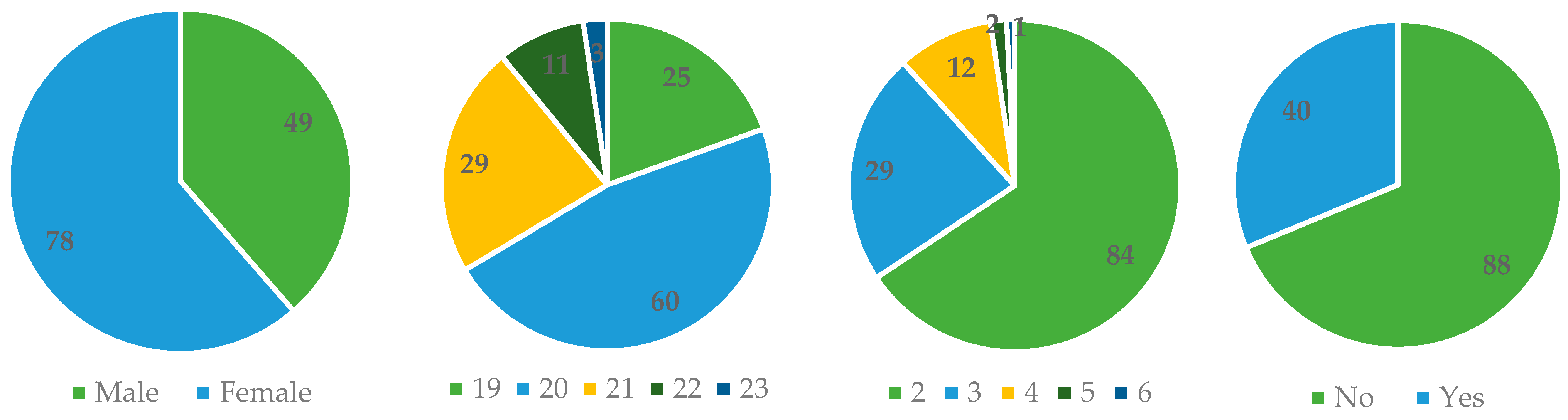

The target population of our study consisted of undergraduate second- and third-year students from the Department of Tourism Management at the University of Patras (Patras, Greece). The study was conducted on 19 May 2024, with 129 participants attending lectures in two core second- and third-year courses within the department. The required sample size, calculated for a -score based on a 90% confidence level and a 5% margin of error, was 116, making our sample size representative of the target population.

All procedures were carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (

World Medical Association, 2024). Participation was entirely voluntary, and the data collection process was designed to ensure complete anonymity. Participants were informed about the purpose of the survey both verbally and in the preface section of the questionnaire, while written consent was obtained to permit the use of the collected data. Completing the questionnaire required approximately 15 min. Since the study did not pose any physical or psychological risks, supervision from an ethical review board was not deemed necessary (

Whicher & Wu, 2015).

3.2. Survey

The deployment of the questionnaire was based on the SERVQUAL quality measurement instrument (

Parasuraman et al., 1988). The instrument was tested in a pilot study, involving staff and students, to determine whether any modifications were necessary.

Several other measurement instruments have been developed (

Moore, 1987;

Heywood-Farmer, 1988;

Beddowes et al., 1988;

Nash, 1988;

Philip & Hazlett, 1997;

Robledo, 2001). However, SERVQUAL remains one of the most popular and widely used, cited, and researched quality assessment methods (

Asubonteng et al., 1996;

Robinson, 1999;

Waugh, 2002) and is therefore highly trusted. Additionally, its design of empirical psychometric testing and trials enables its application across a broad range of service organizations (

Wisniewski, 2001), provided proper adjustments are made. Examples include its successful adaptation for use in higher education (

Broady-Preston & Preston, 1999;

Hill, 1995;

Galloway, 1998) and in tourism (

Puri & Singh, 2018;

Qolipour et al., 2018), which guided our decision to use it.

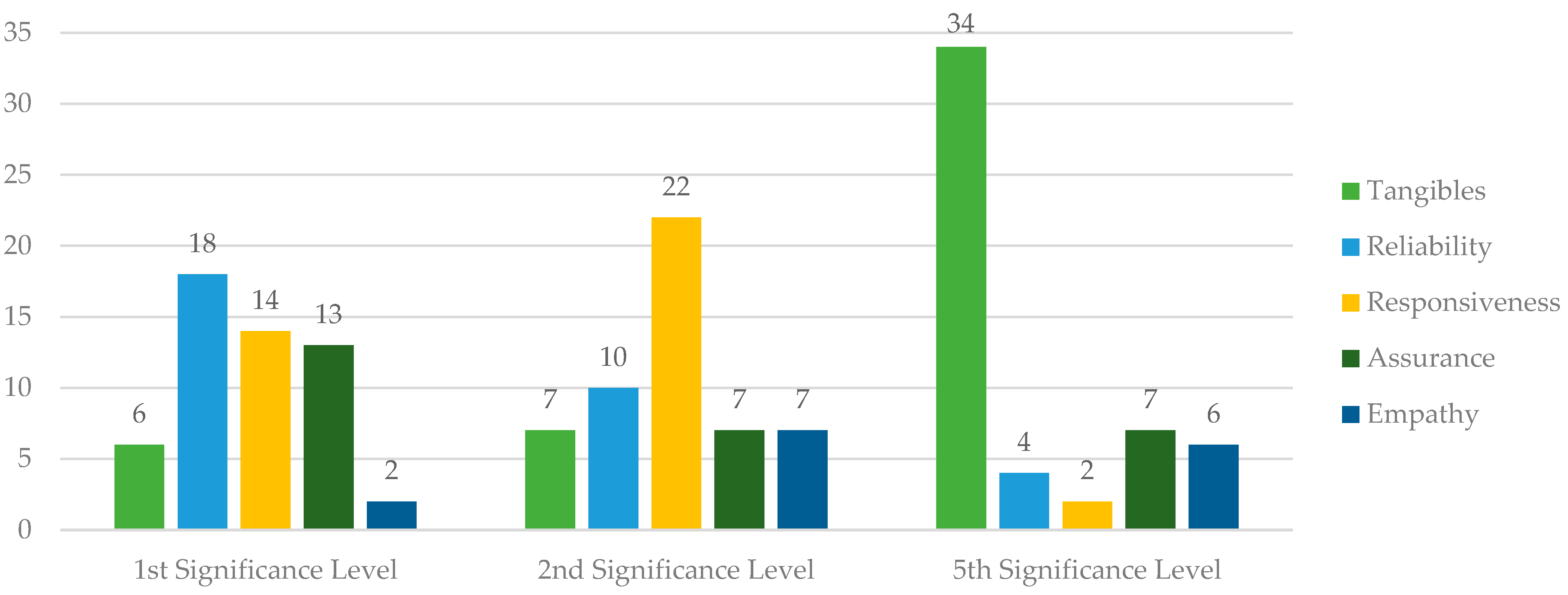

The survey consisted of 4 sections. Section A recorded demographic data, namely, gender, age, year of study, and whether the participant was raised in Athens (the capital of Greece). Section B aimed to capture the perception of service performance through 25 questions addressing each of the instrument’s 5 dimensions. Section C focused on capturing the expectation of service performance, using the same 25 questions, adjusted to reflect the case of an ideal secretariat. Finally, section D sought to determine the order of importance among the dimensions. Students were asked to allocate 100 available points across the dimensions based on their perceived importance. Additionally, section D included 3 direct questions asking participants to rank the dimensions in order of importance. These questions were intended to cross-check whether the point-based allocation aligned with the participants’ stated ranking. In total, the questionnaire consisted of 62 questions: 4 demographics, 25 for perception, 25 for expectation, 5 for point-based ranking, and 3 for cross-checking the rankings.

To ensure relevance in the modern era, the instrument’s questions were adapted to address contemporary advancements, including the role of digital and technological services in administrative support. Moreover, it was tailored to the Greek higher education system. Sections B and C were modified to accept ranges as input (with their endpoints ranging from 0 to 100), rather than relying on a traditional 5-point or 7-point Likert scale, aiming to capture the marginal behavior of underestimation and overestimation. Despite the above changes, the instrument retains its original philosophy intact (

Appendix B.1). To explain the unfamiliar concept, participants were instructed to provide an answer ranging from their worst to their best experience related to the subject of each question. The introductions of sections B and C included multiple examples of demonstrative ranges to help familiarize participants with this concept. Additionally, it was emphasized that there were no “incorrect” ranges, thereby encouraging participants to respond freely and as they deemed appropriate. An electronic/computerized version of the survey could make use of sliders with dual handles, enabling participants to define the positions of both endpoints. This design could facilitate their understanding of the concept of continuous scales without the need for additional clarification.

3.3. Processing

The database containing the survey responses was managed using Microsoft Excel (

Microsoft Corporation, 2018) and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (

IBM Corp., 2023). The results were presented using both software programs. A

-value of less than 0.05 was considered necessary for a finding to be deemed statistically significant. Moreover, the internal reliability of the survey was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha.

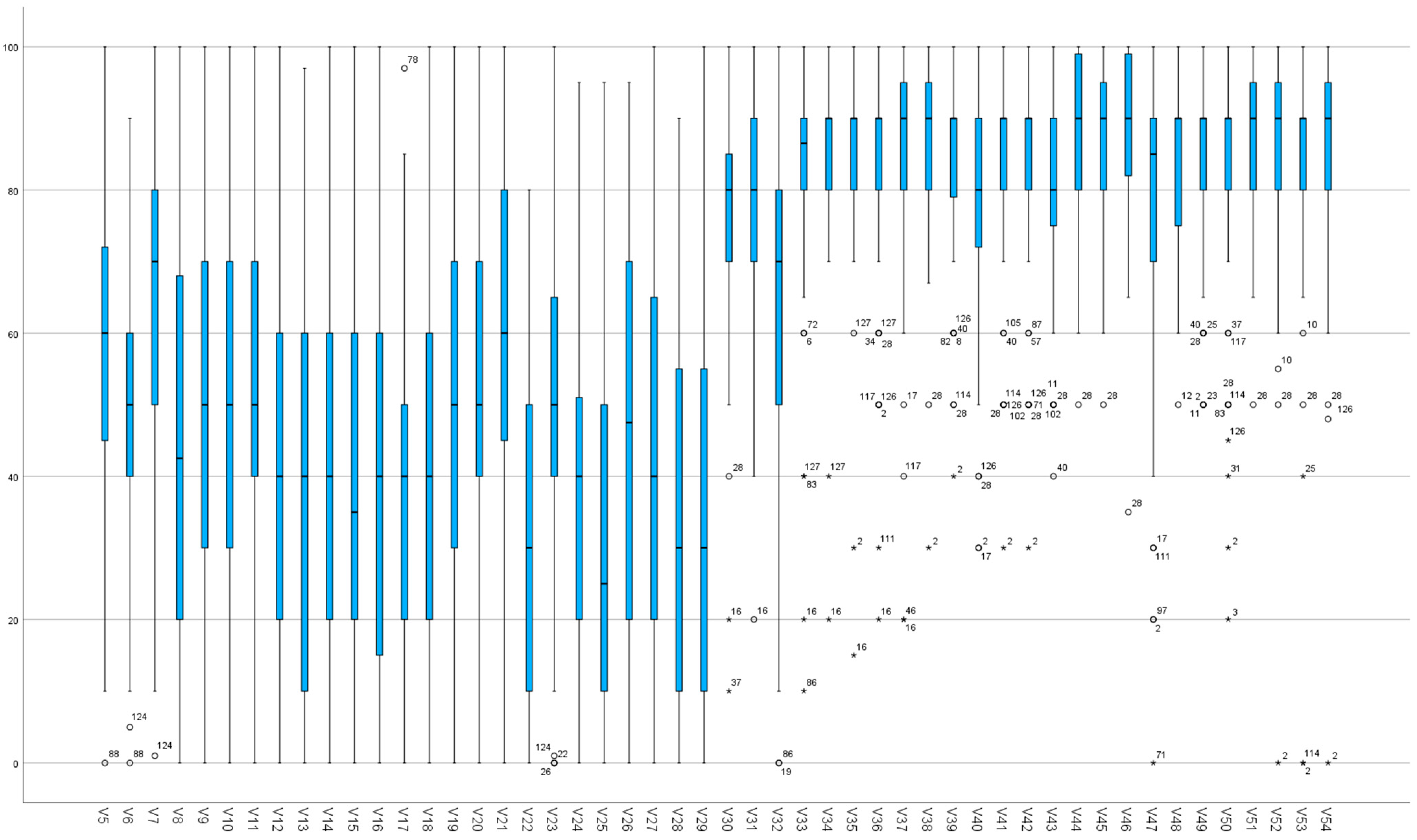

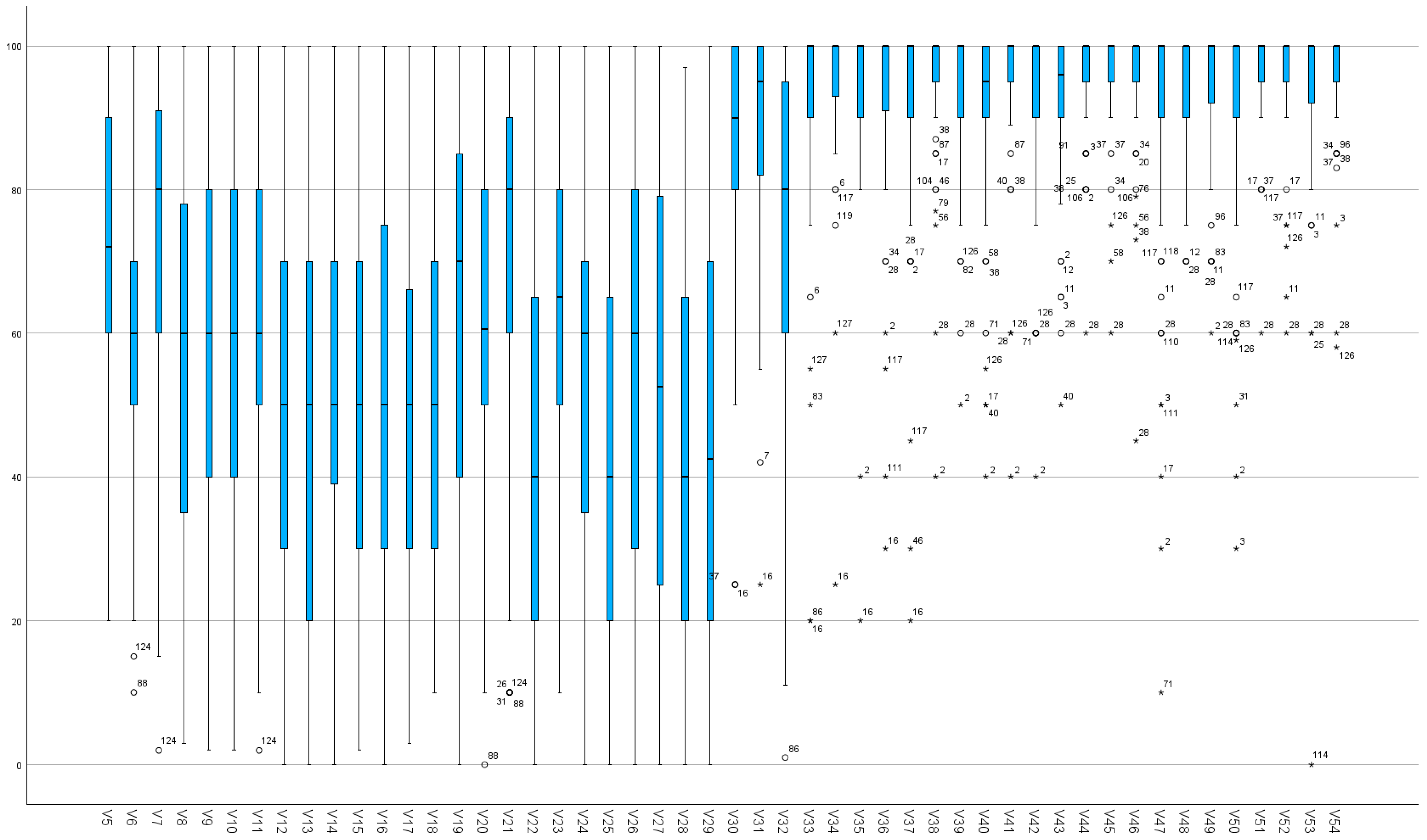

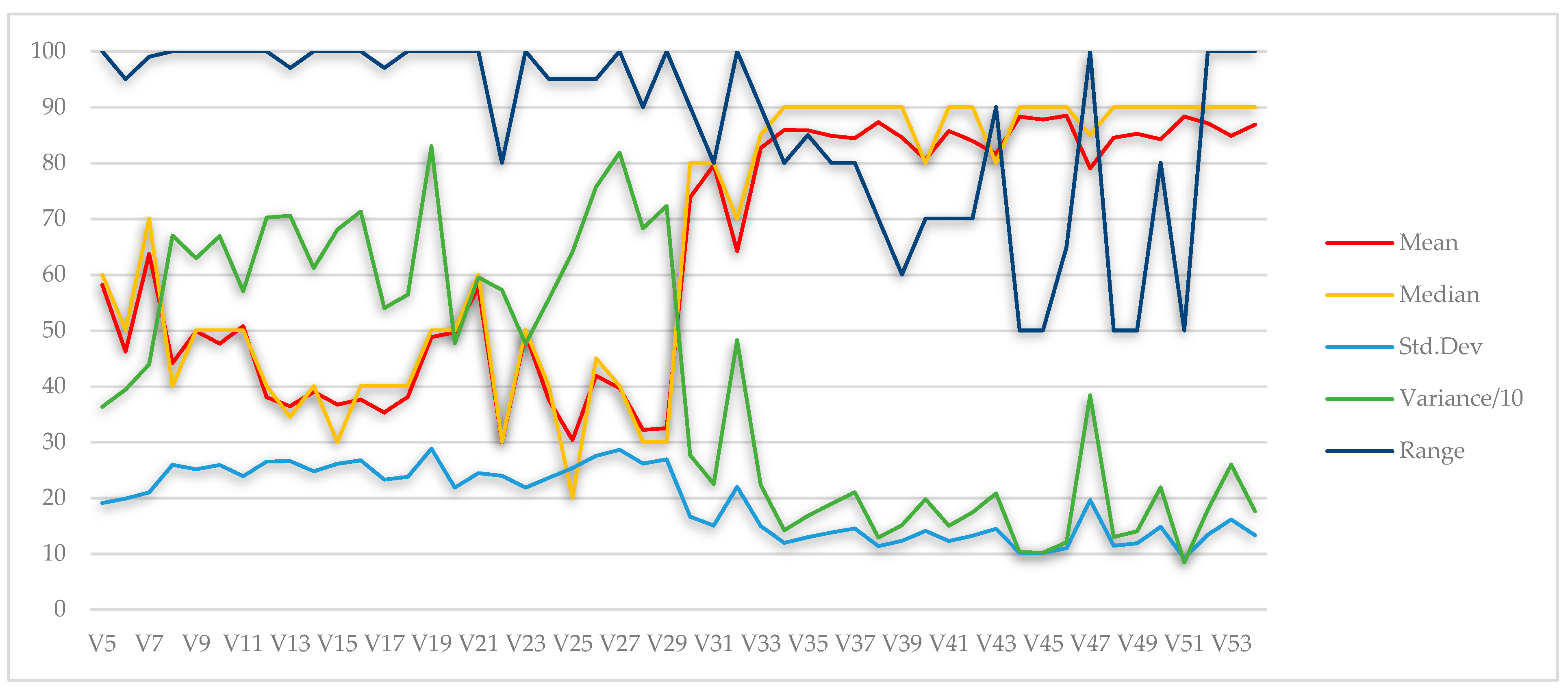

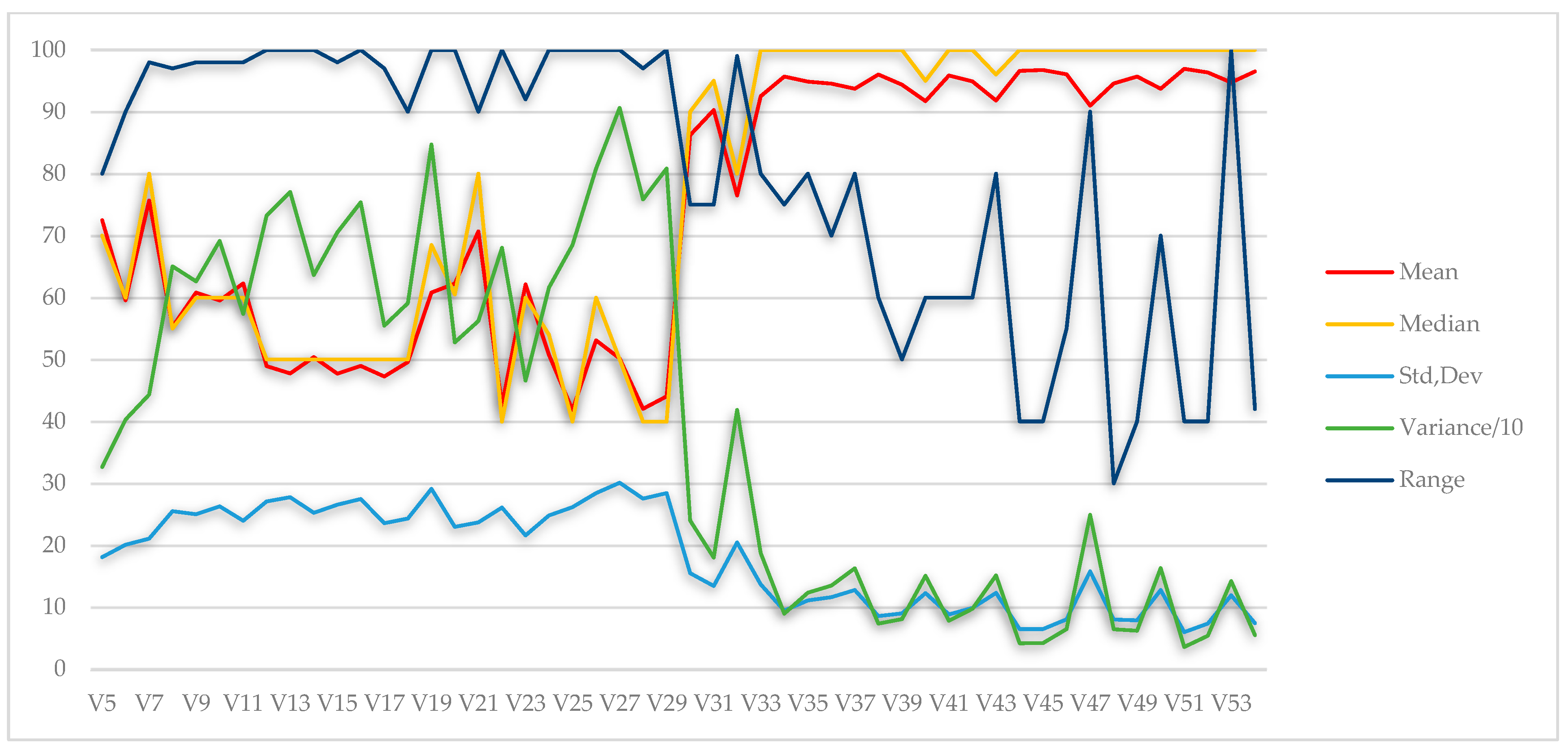

Questionnaires with unsuitable answers in the demographic section (section A) were excluded from the demographic statistical analysis. Additionally, questionnaires with 5 or more unsuitable answers in section B (i.e., 20% or more of the total questions in the section) were excluded from this section’s analysis. Questionnaires excluded from section B were not eligible for inclusion in section C’s analysis. From those included in section B, questionnaires with 5 or more unsuitable answers in section C (i.e., 20% or more of the total questions in the section) were excluded from this section’s analysis. Finally, regarding section D, questionnaires that did not pass the significance level check were excluded from this section’s analysis. Unsuitable answers included the following: no answer, failure to give a range, upside-down ranges, or ranges wider than 39 (considered too wide to provide meaningful information). The limit of 39 was set to prevent answers using more than 2 points on a 5-point Likert scale after conversion.

This protocol resulted in the following exclusions: 2 exclusions from section A (127 valid), 11 from section B (118 valid), 5 additional exclusions from section C (113 valid), and 76 from section D (leaving 53 valid questionnaires after the significance level test).

3.4. Analysis

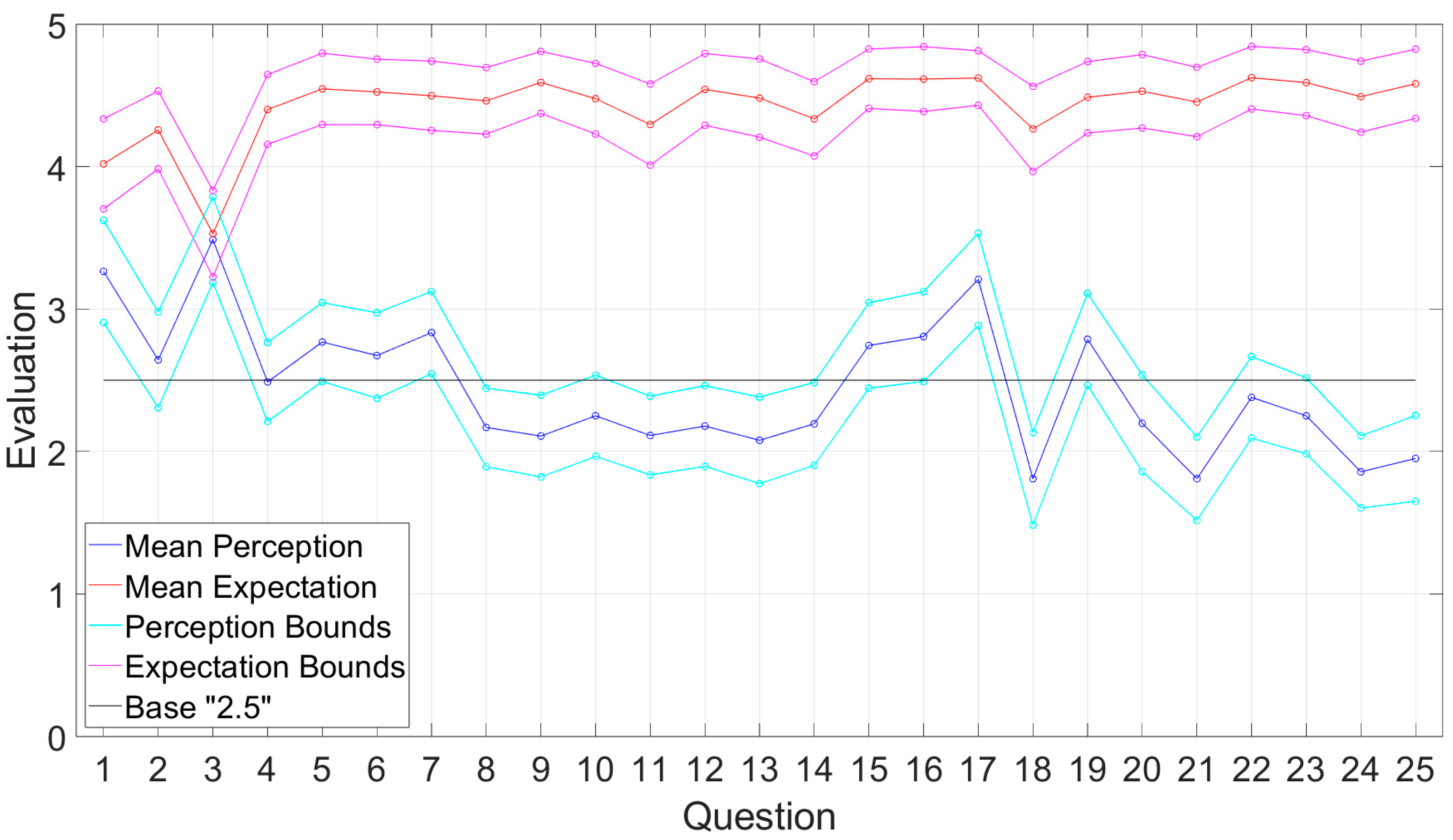

The study of marginal behavior involves two separate analyses: one for the underestimated and one for the overestimated students’ evaluation. Based on the assumption that the actual evaluation of the provided services lies within the area between underestimation and overestimation, we propose the following cases:

C1: If the overestimated perception is lower than the underestimated expectation, then the provided services are deemed unsatisfactory.

C2: If the overestimated expectation is lower than the underestimated perception, then the provided services are deemed highly satisfactory.

C3: If the overestimated perception is higher than the underestimated expectation or if the overestimated expectation is higher than the underestimated perception, then the provided services are deemed satisfactory.

Furthermore, we are allowed to state that the magnitude and consistency of this difference indicate how well established the corresponding conclusion is.

Based on the above assumption and proposed cases, the following results will address the research question of which of these cases applies to this study’s evaluation.

5. Discussion

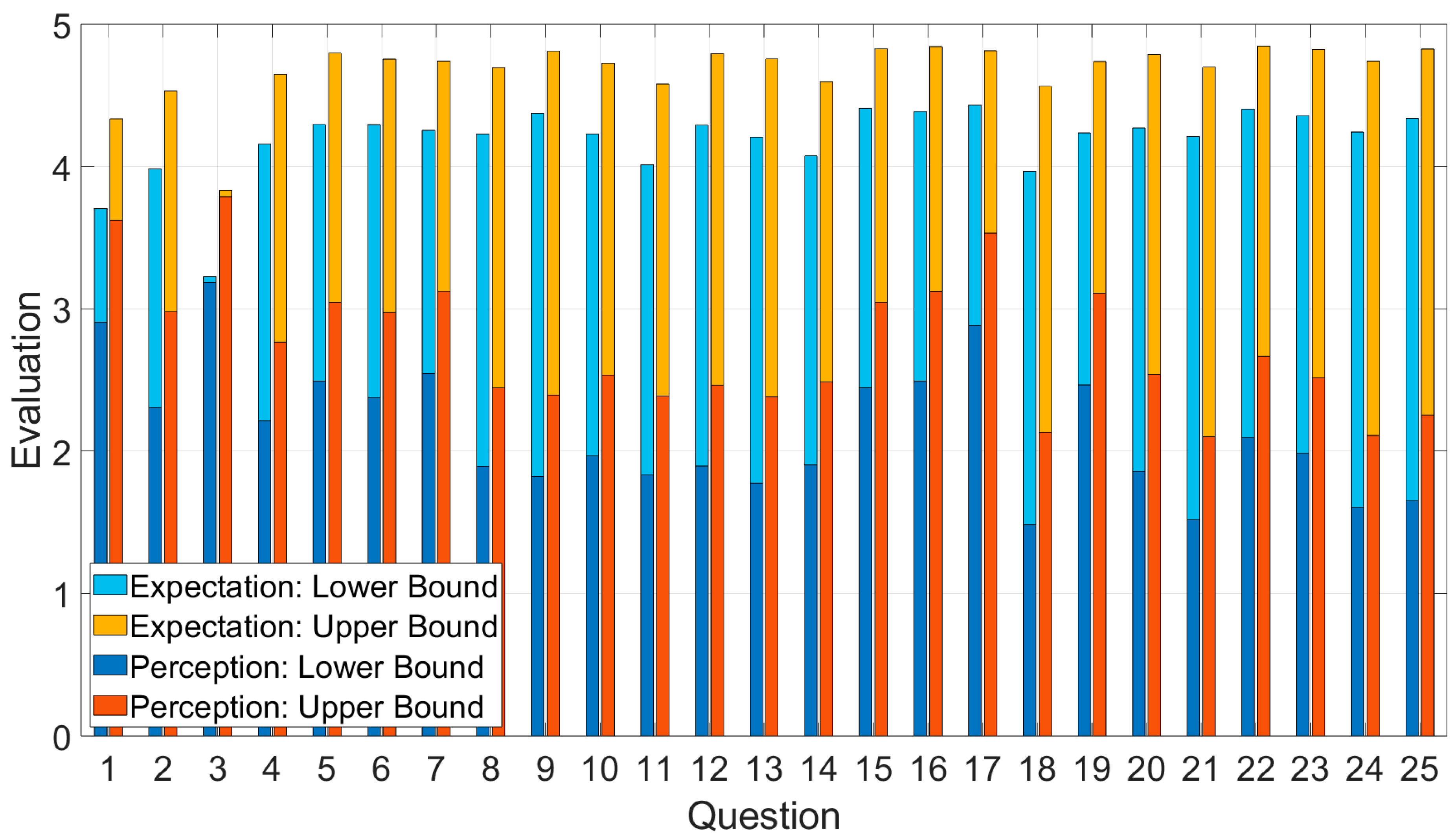

The captured perception of service performance consistently and significantly fell below expectations, thus deeming it unsatisfactory (C1). The magnitude and consistency of this difference indicated that this was a well-established conclusion. The only exception was Q3, which concerned the secretariat’s appropriate appearance, which was deemed adequate. Moreover, 13 of the 25 perceptions were found to be below half of their respective expectations (i.e., below their relative “base”).

With the exception of Q3, the difference between perception boundaries spanned from 1.48 to 3.62. This range was nearly double for the expectation, which spanned from 3.70 to 4.84. Additionally, expectation exhibited significantly more outliers than perception. This phenomenon suggested that students shared a relatively uniform perception of service performance, making perception appear more objective. By contrast, what is considered ideal performance (expectation) varies widely among students, making expectation appear more subjective.

Reliability was identified as the most important dimension, defined as the ability to deliver the promised service accurately. Responsiveness, referring to the willingness to assist customers and provide prompt service, was ranked as the second most important dimension. Finally, the least important was deemed to be tangibles, encompassing facilities, equipment, and personnel appearance. These findings aligned with those reported in similar studies (

Brysland & Curry, 2001;

Donnelly & Shiu, 1999;

Donnelly et al., 1995;

Smith et al., 2007).

Zeithaml et al. (

1990) observed a consistent ranking of service quality attributes, with reliability typically emerging as the most important dimension and tangibles as the least important.

Excluding a few isolated cases, neither age nor whether a student was raised in Athens significantly affected perception or expectation. However, females appeared to evaluate the provided service (perception) more critically than males, with males consistently assigning higher ratings across all affected variables, particularly in the upper endpoints of perception. Notably, no significant difference was detected between male and female expectations.

Furthermore, second-year students were observed to have higher expectations than third-year students, while no significant differences were recorded in their perceptions. Since age did not appear to influence the reduction in expectations, it may be inferred that this decline was not directly related to growing older but rather to department-wise or academic-wise experiences.

Regarding the questionnaire’s completion process, it is worth noting that explaining the concept of continuous scales proved more challenging for participants to understand compared with the traditional Likert scale. Additionally, it was observed that participants tended to follow uniform patterns when completing the survey, with the majority providing endpoints consistently ending in 0 s or 5 s throughout.

The use of continuous scales appeared to provide a more comprehensive assessment compared with traditional Likert scales. By evaluating services using the endpoints of these scales, instead of point values, the proposed modification of SERVQUAL enabled a detailed mapping of the evaluation area between underestimated and overestimated perceptions and expectations of service performance. This allowed a more accurate assessment compared with traditional Likert scales, which only captured an instantaneous mean value, which was, however, described by an inherent variability (

Westland, 2022;

Zeng et al., 2024). The proposed modification enabled the delineation of this variability. Furthermore, when the overestimated perception fell below the underestimated expectation (and vice versa), we had strong indications that they were strictly ordered. Conversely, when the overestimated perception overlapped with the underestimated expectation (and vice versa), we had strong indications they were relatively closed, even if their means appeared ordered—a limitation that would occur with a traditional Likert scale.

As a result, the proposed modification offers greater clarity in identifying the differences between perception and expectation. This enhanced precision offers more enriched insights into service performance and can potentially support the development of better-targeted corrective measures to address specific gaps. Additionally, this approach introduces a new perspective in evaluating tourism services, positioning itself as a valuable novel research tool. However, the approach does have its drawbacks. These include the challenge of explaining the concept of range-based answers to participants, as well as the increased workload it entails: since this method effectively combines two independent analyses—one for underestimation and one for overestimation—it requires additional time and effort to implement.

Using this modified version of the SERVQUAL quality measurement instrument, our study quantified deviations from the expected performance in the services provided by the secretariat of the Department of Tourism Management. This analysis serves as a foundational step toward identifying and implementing appropriate corrective measures. The findings highlight the potential for further research and broader application of this approach in any context where the SERVQUAL tool is utilized.

Research Limitations

The study relied exclusively on a quantitative approach, inherently limiting its scope to quantitative data. Future studies should incorporate a mixed-methods approach, which could enrich the analysis by including qualitative data (e.g., interviews) alongside the quantitative data (e.g., questionnaires), thereby providing deeper insights. For example, qualitative data might help identify specific issues within individual elements of each dimension that received a low rating. It has been suggested that service quality evaluation should not rely solely on fixed-choice questions. Instead, respondents should be given the opportunity to provide open-ended feedback on all aspects of the service they received (

Philip & Hazlett, 2001). The study focused mainly on second-year students, given its pilot nature. To increase generalizability of the findings within the department, future studies should include students from all academic years. Furthermore, the study was limited to a single university department. To achieve broader generalizability, future research should encompass multiple departments and, ideally, other universities as well. These studies should also account for institutional, cultural, or other contextual factors that could potentially affect students’ expectations and perceptions, expanding the list of demographic variables in order to take them into account. Additionally, thorough attention should be paid to ensuring that the phrasing of questions is neutral and independent of such factors, among students, to minimize bias.