Abstract

The level of expenditure by cruise passengers in the various cities visited during their journey is a crucial variable for the key stakeholders involved in this industry. Promoting higher spending by cruise passengers in non-overnight stay ports is a challenge led by the destination manager. This study aims to shed light on the effect that different phases in the cruise passenger’s travel cycle have on their propensity to spend during their stay. Our case focuses on the city of A Coruña, a non-overnight stay port on Europe’s Atlantic arc routes, where the average spending per cruise passenger during their visit is quite low. The analysis considers the impact of passenger profiles and the cruise product consumption phases on the average spending per passenger. From a methodological perspective, we have applied logistic regression. The results indicate that the profile of the cruise passenger, variables related to the onboard journey, and the experience of the city are the factors with the greatest potential to increase cruise passenger spending during their visit to the city. This has allowed the areas of greatest impact and where actions should be focused to be identified for both the destination manager and key stakeholders.

1. Introduction

Cruises are defined as “a mixture of maritime transport, travel, and tourism services, facilitating the leisure activity of passengers paying for an itinerary and, potentially, other services on board, and including at least one night on board on a seagoing vessel having a capacity of at least 100 passengers” [1] (p. 593). As such, they can be considered complex tourism products [2] as they require users to adopt decisions regarding the destination, cruise line, and itinerary [3].

Studying the variables that affect tourist spending is essential for all stakeholders. Our study aims to analyze how a set of predictive variables related to the passenger profile and the cruise travel cycle influence cruise spending during their visit off the ship. Our case study has three unique characteristics: the low average spending by cruise passengers during their visit; the fact that we are dealing with a non-overnight stay port; and its inclusion in an Atlantic route. The results obtained highlight the potential of the various variables and provide action lines that offer decision-making tools for destination managers, tourism businesses in the city, and shipping companies.

The chosen predictors in our exploratory approach are categorized into four sections: cruise passenger profile; travel decision and preparation prior to embarkation; the information received during the voyage and principal pull factors; and the length of time spent in the city as well as the passengers’ assessment of their experience in A Coruña. In line with previous studies that have adopted an exploratory approach, expenditure demand models tend to be based on tourists’ preferences, along with their sociodemographic and economic characteristics [4,5].

A logit model was used to study cruise passengers’ spending decisions in the non-overnight stay port of A Coruña. Data collected via surveys conducted in the port of A Coruña in 2019 were used to estimate our model. The model specifications, which are used as a dependent variable in models studying tourism expenditure per capita per day, have a dichotomous response. The estimated coefficients account for the probabilities that tourist spending will occur, given the independent variables [6].

In short, this article identifies those variables that play a key role in cruise passenger spending in the city of A Coruña. The ultimate goal is to analyze the nature and intensity of the impact on these variables, thereby enabling stakeholders to design strategies and actions that will positively influence cruise passenger spending. All the information generated by this study will enable destination managers to select those cruise passenger segments that are best suited to their offer and identify the most effective marketing strategies that will drive tourism product expenditure.

1.1. The Cruise Industry

1.1.1. Cruise Activity in Europe

On an international scale, 31.7 million passengers took a cruise in 2023, and in 2022, the cruise industry contributed USD 138 billion to the global economy [7] (p. 5). The cruise industry has a multiplying effect on society that is not limited exclusively to the tourism sector.

The principal positive impacts of the cruise industry include increased foreign exchange earnings and tax revenue, employment, and positive externalities, as this sector also drives other economic areas such as shipping and tourism agents, port authorities, towage companies, oil companies, shipping companies, and shipbuilders. In contrast, the negative factors associated with the industry include hikes in the cost of goods and services caused by pressure on demand, the potentially uneven distribution of profits among residents, revenue loss for companies operating outside the cruise sector, and seasonal income for the industry’s workforce [8].

As for the cruise industry’s market structure, it has traditionally been considered oligopolistic or monopolistically competitive [9,10]. In 2022, the cruise market was divided into four main companies that make up most of the market share: Carnival Group (45%), Royal Caribbean International (25%), Norwegian Cruise Line (15%), and MSC Cruises (5%) [11].

In Europe, there was a steep upward trend in the number of ports of call around the world. This trend was halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. In 2021, just three ports (Southampton, Civitavecchia, and Barcelona) handled half a million cruise passenger movements, compared with 34 ports in 2019. Cruise passenger movements in 2020 and 2021 fell by 81% [12].

1.1.2. Cruise Activity in Spain and Galicia

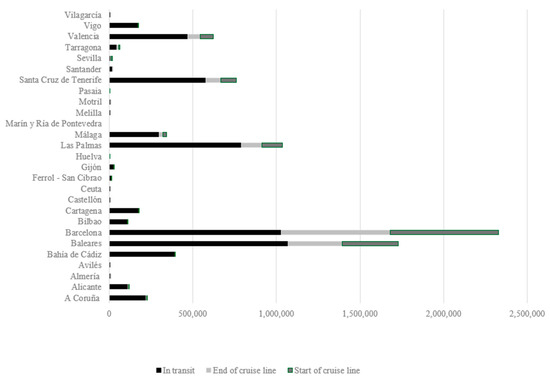

Spain is a country located in the south–west of Europe, bounded by France and Portugal, and an attractive geographical location for shipping companies. Its Mediterranean ports (Alicante, Almería, Balearic Islands, Barcelona, Tarragona, Cartagena, Castellon, Ceuta, Malaga, Melilla, Motril, Tarragona, and Valencia) accounted for 66.6% of the total number of cruise passengers visiting Spanish ports in 2022 [13]. In addition, the busiest cruise ports by passengers (Barcelona and the Balearic Islands) are located in this area (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cruise passengers in Spain 2022. Source: Authors’ own, based on an annual statistical report of the state-owned port system [14].

Galicia’s ports are of vital strategic importance in the international maritime market [15]. There are six ports managed by five port authorities: A Coruña, Vigo, Marín y Ría de Pontevedra, Vilagarcía de Arousa, and Ferrol–San Cibrao. They accounted for just over 4.79% of the total cruise traffic for Spain in the first semester of 2024 [16].

Cruise ship traffic during the first semester of 2024 is mainly concentrated in the Port of A Coruña (68.8% of the total in the Galician Autonomous Community) and Vigo (26.7% of the total) [16].

2. Background and Theoretical Framework

The tourism industry is made up of various stakeholders, such as “lodging, transportation, attractions, food and beverages, retail… which creates a complex value chain” [17] (p. 6). The tourism value chain was proposed by the UNWTO, classifying the activities that take place in the departure country (travel organization and booking) and in the entry country (transportation; accommodation; food and beverage; handicrafts; tourism assets in destination; leisure, excursions, and tours; support services) [17,18]. This generalized approach is applied to the cruise travel sector through its own Cruise Tourism Global Value Chain [19].

The analysis of cruise passenger spending and its determining variables have been addressed from both a macroeconomic and microeconomic perspective [20]. In macroeconomic terms, the focus has been on the impact of cruises on the receiving country [21], while from a microeconomic perspective, cruise passenger spending is considered a key variable for the analysis of the cruise industry’s costs and profits [22]. Our approach has significant implications for destination port managers’ motivation to increase both the number of cruise passengers visiting the city and their expenditure during the visit.

Four types of travel expenditure must be calculated in order to gain a full insight into the economic benefits of cruise tourism in the different ports and regions [23]: (i) crew-related expenditure; (ii) vessel-related expenditure; (iii) support expenditure; and (iv) passenger-related expenditure.

Consequently, this analysis will focus on examining the factors influencing cruise passengers’ spending at visited destinations. Various studies have used passenger expenditure per port as the most common metric to assess cruise passengers’ investment at different destinations [24,25]. Other measures include per capita spending on board and ashore, expenditure by category [26], or per capita spending excluding excursion costs [27].

Larsen et al. [28] showed that cruise passengers spend less at local tourism businesses than land tourists. Despite this, cruise tourism can be a major driving force for the development of port cities. Success in this sense depends on “the operational profile of the market and internal conditions, as well as the port size and facilities” [29] (p. 43).

The characteristics of the trip also play a significant role in determining expenditure [5,6]. Factors such as group size, accommodation, transport, length of stay, reason for travel, age, income, and first-time visit may or may not boost spending in the destination [30]. Other factors, such as passengers’ income or assets, also directly affect the amount of money they spend [7].

The analysis conducted by Park et al. [6] on a sample of 48,113 travelers allowed them to conclude that length of stay and tourist information are both factors that impact spending, albeit not the only ones. Psychological, economic, and sociodemographic considerations also determine spending levels in tourist cities [31]. Sociodemographic factors include gender, civil status, family size, income, place of residence, and occupation [32].

In line with this, and further elaborating on the literature cited above, this article studies the influence of certain travel phase variables on cruise passengers’ spending patterns. Cruise passengers’ total spending in the destination city may be subject to the influence of three key moments: (1) the decision to travel and preparation; (2) the information provided and the decision taken during the voyage; and finally, (3) the visit to the city.

Regarding the decision to travel and preparation phase, cruise passengers tend to purchase all-inclusive holiday packages, and therefore travel agencies are the principal source of commercial growth of the cruise industry as customers tend to trust travel agencies more [33]. Given that cruise passengers frequently opt for all-inclusive holiday packages, travel agencies emerge as the principal drivers of commercial growth within the cruise industry, as consumers tend to place a higher degree of trust in these agencies. According to Andriotis and Agiomirgianakis [34], returning tourists and tourists who were persuaded to visit the city because of experiences reported by others will have additional positive financial impacts on the local economy. This allows us to formulate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The port of call as a decisive factor when booking a cruise has a significant impact on expenditure in the city where the port of call is made.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Information prior to travel has a significant impact on expenditure in the port of call city.

The second moment is the information provided and the decision taken during the voyage. Klein [35] states that cruise companies use various forms of promotion in order to boost onboard sales. Increasingly, companies are promoting their ships as actual destinations rather than as means of transport or hotels that carry tourists to a number of ports [36]. Vogel [37] attributes this principally to their dependence on the additional revenue generated by customers who spend the majority of their holiday on board the ship. Other studies have segmented the results of the impact of expenditure on land excursions by cruise category [38]. Assuming that they are acquired by people with a higher purchasing power, the most expensive cruises have a significantly greater positive impact on spending [39]. Based on this, we have constructed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Information obtained during the voyage has a significant impact on spending in the port of call.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The city’s principal pull factor for cruise tourists (i.e., the built, environmental, historical, and artistic heritage) has a significant impact on spending in the port of call.

The third and final moment is the visit to the city. Penco and Di Vaio [40] argued that the length of time spent in the destination affects spending behavior. Larsen et al. [28] stated that cruise passengers’ spending per hour is similar to that of other tourists. Satta et al. [41] found that the longer cruise passengers spend in the destination, the greater their expenditure in that port will be. As Larsen and Wolf [42] observed, “time is a limited resource for cruise tourists when visiting a destination, and current evidence indicates that increasing the time available would boost per capita spending in any port” (p. 47).

Domènech et al. [24] reported varying spatiotemporal patterns in terms of spending among cruise passengers in Tarragona (Spain). Spending fell when they visited a large number of attractions and increased when they spent longer at the principal landmarks [39]. Henthorne [25] stated that cruise passengers obtain an incomplete impression of the destinations they visit due to the limited time they spend in the ports of call (approximately 5 h). The following hypothesis can therefore be put forward:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The length of time invested in the port of call has a significant impact on spending in the city.

Polykalas et al. [43] emphasized the strong correlation between the satisfaction of cruise passengers and their spending levels during their stay at a visited port. Di Vaio et al. [44] highlighted the positive effect sustainable service satisfaction (physical and socioeconomic environments) has on monetary spending onshore for cruise tourists that visit a location for only a few hours. Additionally, regarding the socioeconomic environment affecting cruise passenger satisfaction, Henthorne [25] observed that cruise passengers are more inclined to spend additional money when they perceive the destination vendor as “friendly”, in reference to the provision of helpful and valuable information.

In relation to academic studies that directly link tourists’ satisfaction to their land-based spending during visits, it is important to highlight the negative consequences that cruises have on the environment and cities due to pollution and overcrowding in various locations [45]. For instance, the saturation of ports such as those in Jamaica [46] or in cities like Barcelona, Venice [44], and the island of Mykonos is particularly notable. Moreover, various authors have examined the eco-efficiency of ship emissions in ports and the environmental costs associated with various ship types and cruise traffic [47,48].

The cruise industry seeks to eliminate these negative externalities in order to enhance passenger satisfaction [46] by promoting sustainability initiatives [49]. Cruise companies aim to comply with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [50], as according to Di Vaio et al. [44], satisfaction with sustainable services (environmental and social sustainability) is positively associated with overall satisfaction.

In this sense, we can propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Cruise passengers’ final rating of the city has a significant impact on spending in the port of call.

A considerable number of published studies have analyzed different models with various psychographic, sociodemographic, and economic covariates [24,51]. These include income, preferences, occupation, age, gender, place of residence, education, marital status, opinions, attitudes, and motivations.

The socioeconomic status of cruise passengers, as indicated in research conducted by Baños and Tovar [52] and Lee and Lee [53], exerts a positive influence on spending patterns.

Regarding cruise passengers’ age, the literature adopts varying stances: Jang and Ham [54] claimed that the over 65s spend more than young people. Marksel et al. [55] emphasized that creating efficient cruise marketing strategies in Slovenia requires identifying key target segments based on their nationality and sociodemographic characteristics. Dardis et al. [56] pointed to a negative relationship between age and tourist expenditure, namely that older adults spend less on tourism. This is consistent with the findings of Baños and Tovar [52], who suggested that encouraging the arrival of younger cruise tourists through specific marketing strategies could increase onshore expenditure. This approach is particularly relevant given the inverse U-shaped relationship between age and tourist spending, where younger tourists are likely to spend more compared to their older counterparts. Finally, Roehl [57], Cai [58], Lee [59], and Marksel et al. [55] found that the statistical relationship between age and tourist spending was insignificant.

These findings lead us to formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Cruise passengers’ age has a significant effect on their spending in the port of call.

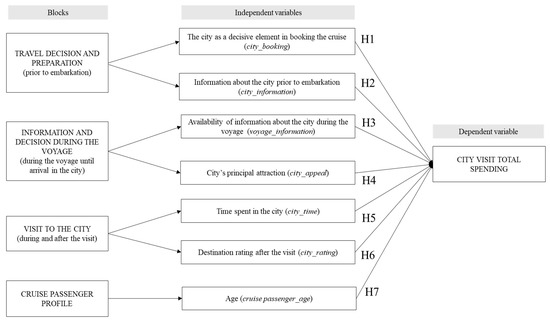

In accordance with the above, a model for predictors affecting cruise passenger spending is proposed, as shown in Figure 2. The aim is to identify the impact on cruise passenger spending in the city of A Coruña (Galicia, Spain) based on passenger profile, travel preparation, information during the voyage, and the visit to the city whilst the ship is moored in port. Age was chosen as the profile variable (Hypothesis 7). As for the travel decision and preparation, two variables were selected: the city as a decisive element in booking the cruise and the information cruise passengers obtain prior to embarkation (Hypotheses 1 and 2). These two variables provide an insight into cruise passengers’ prior interest in the city and its impact on spending while there. Regarding the impact of the information on the city obtained during the voyage, two variables were applied: the publicity given to the city from the cruise ship and the city’s major attractions (Hypotheses 3 and 4). These will allow the study of the impact of the shipping company’s communication on spending in the city. Finally, the length of time spent in the city and cruise passengers’ rating of the city were selected in order to analyze the impact of the visit on spending (Hypotheses 5 and 6).

Figure 2.

The proposed predictive model. Source: Authors’ own.

Furthermore, the proposed model will consider how three points in time impact cruise passengers’ spending in the city: prior to embarkation, whilst on board, and the visit itself. A profile variable was also included in order to verify the impact of endogenous characteristics on the variable under study.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey, Questionnaire, Sampling, and Fieldwork

The target population comprised cruise passengers that disembarked and visited A Coruña or carried out some form of activity in the city during the time their cruise ship was moored in port. The ships called at the port of A Coruña after visiting other ports of call included in the cruise itinerary. The cruise ships do not stay overnight in the port of A Coruña; consequently, all expenditure is made over the course of several hours on a single day. Each cruise ship was selected once only.

Convenience sampling, a non-probability sampling method, was used. This technique implies a sampling bias risk, namely self-selection bias, which may affect the generalization of the results. In order to reduce this bias, the survey participants provided the respondents with a detailed explanation of the objectives. Another key factor in the choice of location was that the survey participants had easy access to the respondents, which contributed positively in terms of the number of fully completed questionnaires.

G*Power 3.1.9.7 software [60,61] was used to define the minimum sample size. The final sample used for this research was collected between 18 September 2019 and 31 October 2019. A total of 314 responses were obtained, 310 of which were valid.

The questionnaire was available in Spanish and English and comprised twenty short questions that required approximately 10 min to complete. It was divided into four sections. Section 1, entitled “Cruise passenger profile”, refers to sociodemographic characteristics; Section 2, “Before embarking on the cruise”, refers to the booking process, prior information about the city of A Coruña, and the cruise duration; Section 3, “Cruise journey before your arrival in the city of A Coruña”, seeks to establish how information about the city was obtained during the voyage, the publicity provided by the shipping company, the purchase of services on board the cruise ship, and A Coruña’s principal visitor attractions; and Section 4, “Visit to the city of A Coruña”, comprises a breakdown of spending, the length of the visit, and the respondents’ final rating of the city.

The questionnaire guaranteed respondent anonymity. No personal data that could identify participants were collected. The survey used in 2019 was tested in 2018 for the same study. Several modifications were made to the initial version in order to adapt it to several questions included in the object of this study. However, it provided a pretest for survey validity.

The fieldwork and data collection were carried out by several survey participants provided by Turismo de A Coruña. They were selected, trained, and supervised by the project managers. The surveys were conducted in person during morning and afternoon sessions at the port access point when the cruise passengers returned from their visit to the city. The survey participants and their work were subject to ongoing monitoring and validation by a supervisor.

3.2. Characteristics of Cruise Passenger’s Profile

Table 1 shows the absolute and relative frequency of the variables sex, country of residence, labor status, traveling companions, number of visits to A Coruña, and the cruise purchase channel. Together, they make up the profile of the cruise passengers included in the sample used. Moreover, 57% of the survey respondents were men and 43% were women. The majority of cruise passengers were from the United Kingdom and Germany, accounting for 75% of the total sample. Fifty-one percent were retired. The majority were traveling with their partner, and for just under 75%, it was their first visit to the city. Travel agencies were the most frequently used channel for booking the cruise (57.7%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cruise passengers’ profile.

3.3. Characteristics of the Variables for the Proposed Model

The model variables were selected in accordance with the questions shown in Table 2 and based on the structure of the questionnaire. The absolute and relative frequency of each response has been included. The variable cruise passenger_age was selected for the section corresponding to the cruise passenger profile. In the initial questionnaire, it was a numerical variable, but this was later modified to over and under 65s due to the interest in analyzing the two most relevant groups in the sample.

Table 2.

Model variables.

In the block entitled “travel decision and preparation”, the city_booking variable was maintained as in the original questionnaire. Originally, city_information was a nominal variable with several options. For the purpose of the analysis, the responses were included under “I sought information” and “I did not seek information”. This is because the object of the research was not to obtain details of the nature of the information search but merely to determine whether or not it took place.

In the block entitled “Information and decision during the voyage”, two variables were selected: voyage_information and city_appeal. The response to the voyage_information variable included four options: three that included publicity and one that corresponded to no publicity. The publicity options were therefore divided into the three most relevant options: “marketing actions by the shipping company”, “sale of excursions”, and “excursion marketing and sales”. The city_appeal variable featured three major options that grouped together the original multiple options: “gastronomy”, “natural environment and scenery”, and “historic–artistic heritage”.

The block corresponding to the visit to the city of A Coruña comprises three variables: cruise passenger_spending, city_time, and city_rating. Cruise passenger_spending is the independent variable that was dichotomized, taking the median as the reference. The city_time variable was rescaled for the purpose of greater clarity regarding the various visit length profiles and the impact on spending. Similarly, the city_rating was also rescaled, given that the data were centered in the upper half of the scale of one to ten (Table 2).

Given the importance of the variable measuring cruise passenger spending in our study, Table 3 presents the main statistics for the variable cruise passenger_spending and the breakdown of this total spending into categories such as food, shopping, transportation, museums, excursions, and others. This information was collected in question 16, “How much did you spend (per person and day) on the following items during your visit to A Coruña?”. The analysis of the results reveals that food and shopping are the two main sources of spending.

Table 3.

Statistics for the breakdown of the variable total cruise passenger spending.

3.4. Analytical Method

Logistic regression methodology was used (logit model) [62]. Logistic regression was used to analyze a relationship of dependency. Therefore, despite the predictive focus, we are also implicitly analyzing the underlying causality between variables. In contrast, other research has employed the ordinary least squares (OLS) model [27], the probit model [53], the logit model and tobit model [63], the tobit model [51], the Heckman model [64], as well as both the tobit and Heckman models [65].

This modeling method is fit for predicting categorical outcomes from categorical and continuous predictors. It allows the identification of those factors that differentiate groups defined by the dependent variable. The idea is rooted in discriminant analysis, but with the advantage of being able to consider any level of measurement of the independent variables. From the point of view of the independent variables, not only qualitative and quantitative variables can be considered and their individual effects on each can be assessed, but also the effect of their interaction.

The data were processed and analyzed with the SPSS 28.0 statistical program for Windows (IBM) through data previously obtained and processed using Microsoft Excel.

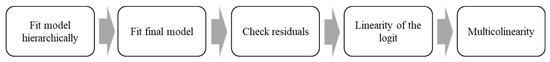

Following Field [66], the phases shown in Figure 3 were used to construct our model. Phase one consisted of the hierarchical analysis of several models, and the most parsimonious was selected. Next, using diagnostic statistics, we looked for indications of bias by detecting outliers (standardized residuals, DFBeta) and influential cases (Cook’s distance and leverage values). There are no unusually high Cook’s distance values (>1), and in practically all cases the leverage values fulfill the rule of thumb of less than 3 * (p/N) and 2 * (p/N). The normalized residuals have values greater than ±1.96 in less than 5% of the cases. All DFBeta values are less than 1. As the model does not include continuous variables, linearity did not have to be checked. Finally, regarding multicollinearity, the tolerance values are greater than 0.1 and the VIF values are less than 10.

Figure 3.

The process of fitting a logistic regression model. Source: Authors’ own, based on Field [66].

4. Results and Discussion

Table 4 shows the modeling results. The variable city_booking (H1) is significant in predicting cruise passenger spending. The model results show that when the city_decisive variable (“Was the city of A Coruña a decisive element in booking the cruise?”) varies from “Yes” to “No”, the cruise passenger expense ratio (odds ratio (Exp(B)) of ≤EUR 20 to ≥EUR 21 falls by 0.366. In other words, the probability of cruise passengers spending ≥EUR 21 drops by 63.4% (while all other variables remain constant).

Table 4.

Model output.

The variable city_information (H2), which includes the information on the city of A Coruña obtained by cruise passengers prior to travel, is not statistically significant.

The variable voyage_information (H3) is significant in predicting cruise passenger spending in terms of the “marketing actions by the shipping company” and “not publicized”. The model results show that when the variable information_voyage (promotion of the city of A Coruña by the shipping company) varies from “marketing actions by the shipping company” to “not publicized”, the cruise passenger expense ratio (odds ratio (Exp(B)) from ≤EUR 20 to ≥EUR 21 falls by 0.170. Specifically, the probability of cruise passengers spending ≥EUR 21 falls by 83.0% (while all other variables remain constant).

The variable city_appeal (H4) is significant in terms of “Gastronomy” and “Natural environment and scenery”. The model results show that when the variable city_appeal varies between the “Gastronomy” and “Natural environment and scenery categories”, the cruise passenger expense ratio (odds ratio (Exp(B)) of spending EUR 21 is multiplied by 3.104. In other words, the likelihood of cruise passengers spending EUR 21 rises by 210.4% (while all other variables remain constant).

The variable city_time (H5) is significant in predicting the spending of cruise passengers when they are in the destination for six hours or longer. The model results show that when the length of time spent in the destination varies from less than three hours to six hours or more, the cruise passenger expense ratio (odds ratio (Exp(B)) of spending EUR 21 is multiplied by 2.825. In other words, the probability of cruise passengers spending EUR 21 rises by 182.5% (while all other variables remain constant).

The variable city_rating (H6) is significant in predicting cruise passenger spending in all categories. The model results indicate that when the destination rating varies from eight or lower to nine and ten, the cruise passenger expense ratio (odds ratio (Exp(B)) of spending EUR 21 is multiplied by 2.266 and 2.408, respectively. This means that the probability of cruise passengers spending EUR 21 rises by 122.7% and 140.8%, respectively (while all other variables remain constant).

The variable cruise passenger_age (H7) is significant in predicting cruise passenger spending. The model results show that when this variable changes from “<65 years” to “65 years”, the cruise passenger expense ratio (odds ratio (Exp(B)) of EUR 20 to EUR 21 falls by 0.483. In other words, this means that the probability of cruise passengers spending EUR 21 falls by 51.7% (while all other variables remain constant).

The results obtained qualify the initial hypotheses. Although cruise passengers that consider the city of A Coruña as a decisive element for their trip during the decision and preparation phase are likely to spend more, it is interesting to note that prior information is not a significant variable. A number of studies, such as those by Casaló et al. [67] and Fandos and Flavián [68], applied the city_information variable in non-tourist contexts and found no significant effect in terms of satisfaction. Conversely, Sanz-Blas et al. [69] claimed that using online sources to obtain information about the destination increased tourists’ satisfaction levels due to the variety of information available.

As was to be expected, promotion actions by the shipping companies during the voyage increase spending, while the absence of this type of promotion reduces it. Cruise companies’ interest in publicizing the destination and the degree of attention paid by cruise passengers to this publicity are therefore both crucial factors for consideration.

Spending increases among those cruise passengers that consider gastronomy and, in particular, the natural environment and scenery to be the city’s principal pull factors. This has major implications for the correct positioning of the city brand, as the historic–artistic heritage is not statistically significant. Local authorities should work with cruise companies to intensify activities related to gastronomy, the natural environment, and scenery, as tourists are displaying a growing interest in experiencing the customs of the local communities in the destinations they travel to [62]. This is in line with earlier studies, which have shown how shipping companies use a range of marketing actions to boost sales [35,36,37].

During the actual visit to the city, only those cruise passengers that spend the longest time visiting the city are significant, which results in notably higher expenditure. Spending longer in the city increases the probability of purchasing a higher number of products and services. In turn, cruise passengers that rate the city visit with a score of nine or higher are likely to spend more, as this group is particularly satisfied with the city’s offer and their expectations have been met or even exceeded. This is in line with Henthorne [25], who stated that sales staff perceived as helpful will motivate greater tourist spending.

Finally, the age variable, associated with the cruise passenger profile, indicates that participants over the age of 65 and those who are retired are less likely to spend money at the destination. This is in line with Dardis et al. [56], Brida and Risso [22], Parola et al. [70], and Brida et al. [71], who found that spending was higher among younger age groups. However, this contradicts the findings of Henthorne [25], Gargano and Grasso [72], and Baños Pino and Tovar [51], who stated that spending in the destination was higher among older adults.

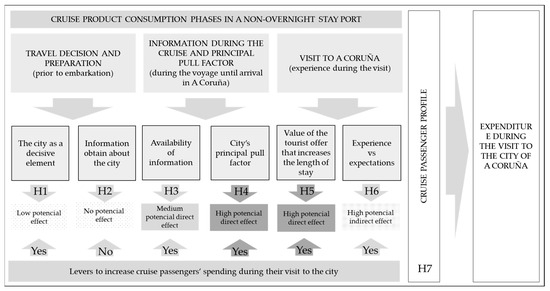

Lastly, based on the results obtained, we have drawn up an initial outline for an expenditure model in non-overnight stay ports. The objective is to enable stakeholders (namely shipping companies, the city’s tourism businesses, institutions, and tourist destination managers) to channel their strategic efforts in cruise tourism. The model includes the principal levers for action aimed at driving cruise passenger spending (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The expenditure impact model in a port where there is no overnight stay. Source: Authors’ own.

We have identified three main phases in cruise product consumption, with two hypotheses associated with each phase. The exception is the cruise passenger profile, which serves as the identifier for our case study. The phases and hypotheses encompass essential aspects that focus on the objectives and potential strategies and actions that destination managers could use to design and implement a master plan aimed at driving tourists’ spending when visiting the city.

In our case study, the high potential direct effect lies in the pull factor and the city experience, which can lead cruise passengers to use the maximum amount of time available to visit the city. Therefore, destination managers should center their efforts on communicating and coordinating with destination management companies in the city in order to create tourist products tailored to this specific customer type.

As for the stage of the cruise leading up to the city visit, coordination and commercial action with shipping companies emerge as highly relevant complementary elements for initiatives in areas with the highest potential.

We also identified a high potential indirect effect for those cruise passengers whose expectations are met or even exceeded by their experience. This represents a significant area for implementing policies that encourage return visits and generate positive word-of-mouth publicity regarding the experience. Pre-embarkation appears as the least effective for employing resources for promotional actions and should therefore only be explored after other avenues have been exhausted.

5. Conclusions

Our work is based on the study of an Atlantic port that is a non-overnight stay port with limited relevance on a national scale, despite its considerable importance within its catchment area. Expenditure during the visit to the city is a variable with significant potential for growth, given the low baseline from which it starts.

The main conclusions can be grouped according to the phases the cruise passengers have experienced. The key levers to increase the average spending of cruise passengers are concentrated in the stages of the journey prior to docking and during the visit to the city.

Both the marketing actions by the shipping company and the preference for the natural environment and scenery are important factors for higher spending by cruise passengers.

The type of city and the brevity of the visit emerge as two significant variables in understanding this phenomenon. During the visit to the city, the levers are based on maximizing the available time, supported by the value of its tourism offerings, and ensuring a satisfactory city experience in line with the expectations generated. Lastly, it appears that passengers under 65 years of age have the most attractive profile with the greatest potential impact on spending.

Our conclusions are of particular interest to the various stakeholders involved in promoting the city of A Coruña, and, in particular, for the destination’s tourism managers and the companies that make up the city’s tourist ecosystem.

The principal implications of this study and the results obtained can be directly applied by the destination management body, as they shed light on the levers that can be used to draw up and coordinate effective policies that will drive potential spending by cruise passengers. In turn, the shipping companies will acquire a greater awareness of the city’s potential in order to create more complex products that can be marketed during the cruise. Finally, the results point to areas in which the city’s tourism companies can design specific products tailored to cruise passengers’ preferences.

The sensitivity to spending detected in a number of the model variables confirms the value of the activities that destination managers could introduce and the potential outcomes of certain policies. These include their capacity to drive the development of specific products (such as routes, gastronomy, and the sale of products) by coordinating sector-related businesses in joint projects that would encourage cruise passengers to stay in the city for the maximum time available and therefore increase opportunities for spending. Essentially, the goal is to become a promoter of differentiated tourist products for this customer segment, which requires the solid positioning of the city based on a clearly defined and consistent long-term strategy.

Although the results obtained are based on a specific Atlantic itinerary, our study does pave the way for future lines of research addressing non-overnight stay ports eager to increase their impact in terms of cruise passenger spending. In this sense, now that the situation has stabilized following the COVID-19 pandemic, comparative studies can be conducted over time that transcend the temporal limitations of our case study. It has also laid the foundations for a future theoretical project for the creation of an initial general expenditure model in that kind of port.

Likewise, our study opens up four further lines of research: the generalization of the results to other ports located on similar itineraries; expanding the study of how the city’s image, characteristics, and offerings influence spending during the visit, with a particular focus on complex variables such as the information provided during the voyage and prior to arrival; the potential for satisfied cruise passengers to return and also publicize the destination; and measuring the impact of policies designed to boost cruise passengers’ spending during their visit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; methodology, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; software, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; validation, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; formal analysis, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; investigation, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; resources, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; data curation, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; writing—review and editing, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; visualization, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; supervision, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; project administration, J.-P.A.-V., S.L.M. and A.T.-F.; funding acquisition, J.-P.A.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the CENP Nuevas Profesiones A Coruña under Grant INV09919, as part of a project financed by the A Coruña City Council in collaboration with the Universidade da Coruña Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical review and approval of this study, based on a technical consultancy, was not necessary due to the Regulations of the Teaching and Research Ethics Committee of the University of A Coruña (https://www.udc.es/es/ceid) (accessed on 5 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consents were obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Zenodo repository at https://zenodo.org/records/10073457 (accessed on 5 November 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, and the funders had no role in the design of this study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Pallis, A. Cruise Industry. In International Encyclopedia of Transportation; Vickerman, R., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 5, pp. 593–599. [Google Scholar]

- Adukaite, A.; Inversini, A.; Cantoni, L. Examining user experience of cruise online search funnel. In Design, User Experience, and Usability. Web, Mobile, and Product Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Petrick, J.F.; Li, X.; Park, S.Y. Cruise passengers’ decision-making processes. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2007, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.W.; Wu, C.L.; Lu, J.L. Exploring the interdependency and determinants of tourism participation, expenditure, and duration: An analysis of Taiwanese citizens traveling abroad. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 649–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Woo, M.; Nicolau, J.L. Determinant factors of tourist expenses. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Scuderi, R. Determinants of tourist expenditure: A review of microeconometric models. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruise Lines International Association. State of the Cruise Industry, Cruise Lines International Association. Available online: https://cruising.org/-/media/clia-media/research/2024/2024-state-of-the-cruise-industry-report_updated-050824_web.ashx (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Sambracos, E. Recent Evolution of Cruise Activities in European Ports of Embarkation: A Quantitative and Economic Approach. Arch. Econ. Hist. XXVI 2014, 1, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, O.A. The economics of cruising: An application to the short ocean cruise market. J. Tour. Stud. 1996, 7, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, M. Onboard revenue: The secret of the cruise industry’s success? In Cruise Sector Growth: Managing Emerging Markets, Human Resources, Processes and Systems; Papathanassis, A., Ed.; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Cuota de Mercado de los Principales Grupos de Líneas de Cruceros en el Mundo en 2022. Available online: https://es-statista-com.accedys.udc.es/estadisticas/569657/principales-grupos-de-industria-de-cruceros-en-el-mundo-cuota-de-mercado/ (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Risposte Turismo. Trends and Perspectives in the EuroMed Cruise Tourism; Cruise Lines International Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Puertos del Estado. España recupera el pulso del turismo de cruceros. Puertos del Estado. Available online: https://www.puertos.es/comunicacion/espana-recupera-el-pulso-del-turismo-de-cruceros (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Puertos del Estado. Annual Statistical Report of the State-Owned Port System 2022. Available online: https://www.puertos.es/datos/estadisticas/anuales (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Del Río Rama, M.C.; Álvarez-García, J.; Sereno-Ramírez, A.; Durán Sánchez, A. El potencial del turismo de cruceros en Galicia. Estudio de caso. Tour. Hosp. Int. J. 2015, 5, 135–159. [Google Scholar]

- Turismo de Galicia. Pasaxeiros de Cruceiros nos Portos de Galicia. Xunta de Galicia. Available online: https://aei.turismo.gal/osdam/filestore/1/2/6/9/0/9_285fe2c84440f56/126909_abec0048c1b1a61.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Milicevic, K. Tourism Value Chain and Sustainability Certification; Labelscape Interreg Mediterranean-European Union: Aqaba, Jordan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DEVCO & UNWTO. Sustainable Tourism for Development; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, J.; Fernandez-Stark, K. Barbados in the Cruise Tourism Value Chain; Duke Global Value Chain Center, Duke University: Durham, NC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brida, J.G.; Lanzilotta, B.; Moreno, L.; Santiñaque, F. A multivariate prediction copula model to characterize the expenditure categories in tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 45, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Zapata, S. Cruise tourism: Economic, socio-cultural and environmental impacts. Int. J. Leis. Tour. Mark. 2010, 1, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Risso, W.A. Cruise passengers expenditure analysis and probability of repeat visit to Costa Rica: A cross-section data analysis. Tour. Anal. 2010, 15, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Forsyth, P. Economic significance of cruise tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doménech, A.; Gutiérrez, A.; Anton-Clavé, S. Cruise passengers’ spatial behaviour and expenditure levels at destination. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2020, 17, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henthorne, T.L. An analysis of expenditures by cruise ship passengers in Jamaica. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Osti, L.; Disegna, M. The effect of authenticity on visitors’ expenditure at cultural events. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 16, 266–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuellar-Río, M.; Kido-Cruz, M.T. Perfil y Análisis del gasto del Crucerista: El Caso de Bahías de Huatulco (México). Cuad. Tur. 2008, 22, 47–78. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, S.; Wolff, K.; Marnburg, E.; Øgaard, T. Belly full, purse closed: Cruise line passengers’ expenditures. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 142–148. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanidaki, E.; Lekakou, M. Cruise carrying capacity: A conceptual approach. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 13, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcussen, C.H. Determinants of tourist spending in cross-sectional studies and at Danish Destinations. Tour. Econ. 2011, 17, 833–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernini, C.; Fang, F. Living standard and Chinese tourism participation. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B.K.; Nayak, R.; Mahalik, M.K. Factors affecting domestic tourism spending in India. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.M.; Yang, C.H.; OLeary, J.T.; Nadkarni, N. Comparative profiles of travellers on cruises and land-based resort vacations. J. Tour. Stud. 2003, 14, 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Andriotis, K.; Agiomirgianakis, G. Cruise visitors’ experience in a Mediterranean port of call. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.A. Cruise Ship Squeeze—The New Pirates of the Seven Seas; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D. Environmentally sustainable cruise tourism: A reality check. Mar. Policy 2002, 26, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, M.P. Monopolies at Sea: The Role of Onboard Sales for the Cruise Industry’s Growth and Profitability. In Tourism Economics: Impact Analysis; Matias, A., Nijkamp, P., Sarmento, M., Eds.; Springer Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelbeg, Germany, 2011; pp. 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Georgsdottir, I.; Oskarsson, G. Segmentation and targeting in the cruise industry: An insight from practitioners serving passengers at the point of destination. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 8, 350–364. [Google Scholar]

- Casado-Díaz, A.B.; Navarro-Ruiz, S.; Nicolau, J.L.; Ivars-Baisal, J. Expanding our understanding of cruise visitors’ expenditure at destinations: The role of spatial patterns, onshore visit choice and cruise category. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penco, L.; Di Vaio, A. Monetary and non-monetary value creation in cruise port destinations: An empirical assessment. Marit. Policy Manag. 2014, 41, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satta, G.; Parola, F.; Penco, L.; Persico, L. Word of mouth and satisfaction in cruise port destinations. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S.; Wolff, K. Exploring assumptions about cruise tourists’ visits to ports. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 17, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polykalas, S.; Sgora, A.; Konidaris, A. Cruise Passengers’ Expenditures in Relation to Satisfaction Levels in a Mediterranean Port of Call. In Strategic Innovative Marketing Tourism; Kavoura, A., Borges-Tiago, T., Tiago, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 797–805. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vaio, A.; López-Ojeda, A.; Manrique-de-Lara-Peñate, C.; Trujillo, L. The measurement of sustainable behaviour and satisfaction with services in cruise tourism experiences. An empirical analysis. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 45, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeill, T.; Wozniak, D. The economic, social, and environmental impacts of cruise tourism. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.J.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of stress related to cruise tourism development. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2017, 14, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, B.; Tichavska, M. Environmental cost and eco-efficiency from vessel emissions under diverse SOx regulatory frameworks: A special focus on passenger port hubs. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 83, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichavska, M.; Tovar, B.; Gritsenko, D.; Johansson, L.; Jalkanen, J.-P. Air emissions from ships in port: Does regulation make a difference? Transp. Policy 2019, 75, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. The two market leaders in ocean cruising and corporate sustainability. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida Ramôa, C.E.; da Silva Flores, L.C.; Herle, F.B. Environmental sustainability: A strategic value in guiding cruise industry management. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2019, 3, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños Pino, J.F.; Tovar, B. Explaining cruisers’ shore expenditure through a latent class tobit model: Evidence from the Canary Island. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 1105–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños, J.F.; Tovar, B. Estimating cruise passenger’s expenditure: A censored system approach. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Lee, M.K. Estimation of the shore excursion expenditure function during cruise tourism in Korea. Marit. Policy Manag. 2017, 44, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.S.; Ham, S. A double-hurdle analysis of travel expenditure: Baby boomer seniors versus older seniors. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marksel, M.; Tominc, P.; Bozičnik, S. Cruise passengers’ expenditures: The case of port of Koper. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardis, R.; Derrick, F.; Lehfeld, A.; Wolfe, K.E. Cross-section studies of recreation expenditures in the United States. J. Leis. Res. 1981, 13, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehl, W. Highway accessibility and regional tourist expenditures. J. Travel Res. 1993, 31, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.A. Relationship of household characteristics and lodging expenditure on leisure trips. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 1999, 6, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C. Determinants of recreational boater expenditures on trips. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- López-Roldán, P.; Fachelli, S. Metodología de la Investigación Social Cuantitativa; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/129382 (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Brida, J.G.; Bukstein, D.; Tealde, E. Exploring cruise ship passenger spending patterns in two Uruguayan ports of call. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 18, 684–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellani, A.; Brida, J.G.; Lanzilotta, B. El turismo de cruceros en Uruguay: Determinantes socioeconómicos y Comportamentales del gasto en los puertos de desembarco. Rev. Econ. Rosario 2017, 20, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brida, J.G.; Fasone, V.; Scuderi, R.; Zapata Aguirre, S. Exploring the determinants of cruise passengers’ expenditure at ports of call in Uruguay. Tour. Econ. 2014, 20, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage Edge: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://edge.sagepub.com/field5e (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Casaló, L.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. The role of perceived usability, reputation, satisfaction and consumer familiarity on the website loyalty formation process. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandos, C.; Flavián, C. Consequences of consumer trust in PDO food products: The role of familiarity. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2011, 20, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Blas, S.; Buzova, D.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E. Investigating the moderating effect of information sources on cruise tourist behaviour in a port of call. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, F.; Satta, G.; Penco, L.; Penco, L.; Persico, L. Destination satisfaction and cruiser behavior: The moderating effect of excursion package. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 13, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Brida, J.G.; Lanzilotta, B.; Pereyra, J.S.; Pizzolon, F. A nonlinear approach to the tourism-led growth hypothesis: The case of the MERCOSUR. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 647–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, R.; Grasso, F. Cruise passengers’ expenditure in the Messina port: A mixture regression approach. J. Int. Stud. 2016, 9, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).