Understanding the Influencing Factors of Pro-Environmental Behavior in the Hotel Sector of Mauritius Island

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To compare different theories of behavior and apply the elaborated version of the TPB to the analysis of tourists’ behaviors;

- To isolate the factors that determine tourist consumption patterns within hotels;

- To offer specific consultancy concerning how understanding the behaviors of consumers may, in turn, enhance the hotel industry’s sustainability.

2. A Literature Review

2.1. Understanding Consumption Patterns in Hotels

2.2. Theories of Behavior as Applied to the Tourism Industry

2.3. Extended TPB Variables Applied to This Research

2.3.1. Environmental Commitment and Attitudes

2.3.2. Environmental Concerns and Attitudes

2.3.3. Environmental Consciousness and Attitudes

2.3.4. Environmental Knowledge and Behavioral Intention

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Population and Sample Size

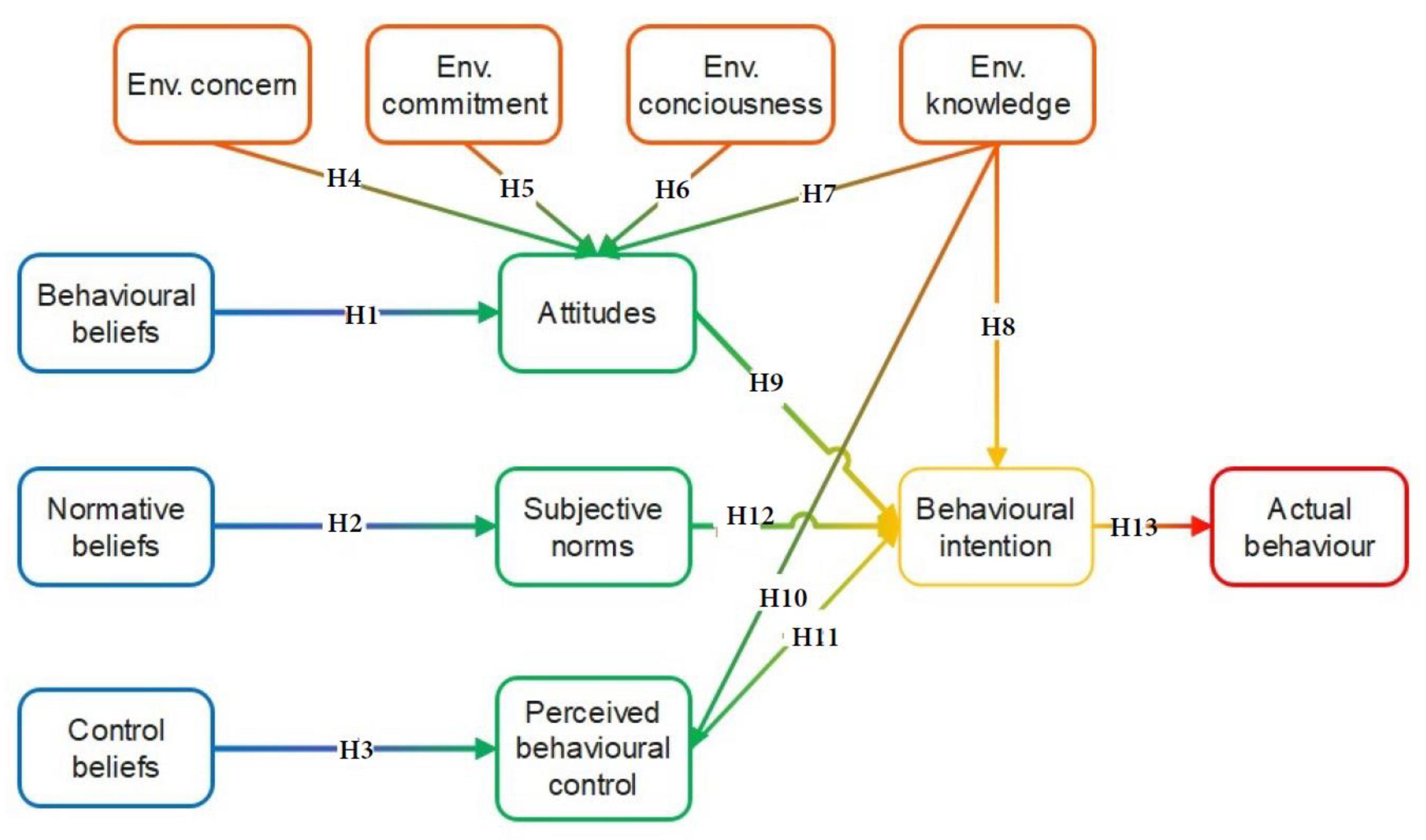

3.3. Conceptual Framework

3.4. Data Collection Instrument

- Demographic Information: The factors are gender, age, educational level, income level, marital status, and country of origin;

- Past Experiences/Behaviors: Based on the items that evaluated the respondent’s past experiences with sustainable practices;

- Moral Norms: Studies checking the level of perceived moral responsibility with regard to PEB;

- Personal Beliefs: In this study, the following products describe the respondents’ perceptions of the benefits of PEB in general;

- Perceived Value: Items that reflect the attitude of the customers in as much as the benefits they are likely to derive by booking and staying at ecologically friendly hotels;

- Motivation: The ISQ self-estimates items that involve perceived autonomy, competence, and relatedness, along with items and responses pertaining to the participants’ reasons and motivations to participate in PEB other than the self-serving financial gains;

- Willingness to Pay More: Products quantifying the consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for green hotel services;

- Attitudes, Subjective Norms, and Perceived Behavioral Control: Product and other TPB-based concepts and items;

- Environmental Commitment, Concern, Consciousness, and Knowledge: PPE-related items to measure other factors influencing PEB other than thermal comfort.

3.5. Procedure

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.1.1. Reliability Analysis

4.1.2. Multiple Regression Analysis

4.2. Model Summary

- R-squared: 0.42;

- Adjusted R-squared: 0.40;

- F-statistic: 16.35;

- Prob (F-statistic): <0.01.

4.3. Interpretation of Hypothesis Tested

- H1: Attitude → Behavioral Intention

- H2: Normative Beliefs → Subjective Norms

- H3: Control Beliefs → Perceived Behavioral Control

- H4: Environmental Concern → Attitude

- H5: Environmental Commitment → Attitude

- H6: Environmental Consciousness → Attitude

- H7: Environmental Knowledge → Attitude

- H8: Environmental Knowledge → Behavioral Intention

- H9: Attitude → Behavioral Intention

- H10: Environmental Knowledge → Perceived Behavioral Control

- H11: Behavioral Intention → Perceived Behavioral Control

- H12: Subjective Norms → Behavioral Intention

- H13: Behavioral Intention → Actual Behavior

Hypothesis Summary

Accepted Hypotheses with Positive Relationships

Rejected Hypotheses

Evolution of Hypotheses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNFCCC. Republic of Turkey Intended Nationally Determined Contribution. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/The_INDC_of_TURKEY_v.15.19.30.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Daneshwar, D.; Revaty, D. A Paradigm Shift towards Environmental Responsibility in Sustainable Green Tourism and Hospitality. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Hum. Res. 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ren, Y.T.; Xuan, L.X.; Ruidong, C.R.; Zuo, J. Exploring the heterogeneity in drivers of energy-saving behaviours among hotel guests: Insights from the theory of planned behaviour and personality profiles. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 99, 107012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M. Insights for Pro-Sustainable Tourist Behavior: The Role of Sustainable Destination Information and Pro-Sustainable Tourist Habits. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.; Gomes, C.; Malheiros, C.; Lima Santos, L. Hospitality Environmental Indicators Enhancing Tourism Destination Sustainable Management. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, A.M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Customer Behavior Associated with Hotels in Zanzibar. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 2022, 22, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Johnson, L. Understanding Tourist Behavior and its Environmental Impact: A Review of the Literature. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 567–585. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.; Davis, M. The Role of Tourist Behavior in Sustainable Tourism: A Critical Review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Olya, H.; Altinay, L.; Farmaki, A.; Kenebayeva, A.; Gursoy, D. Hotels’ Sustainability Practices and Guests’ Familiarity, Attitudes and Behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrevska, B.; Terzić, A.; Andreeski, C. More or Less Sustainable? Assessment from a Policy Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, H.L.T.; Lee, J.S.; Han, H. How do green attributes elicit pro-environmental behaviors in guests? The case of green hotels in Vietnam. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, A.; Kondolf, G.M. How Eco is Eco-Tourism? A Systematic Assessment of Resorts on the Red Sea, Egypt. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, K.P.; Nguyen, T.H.D. The green accommodation management practices: The role of environmentally responsible tourist markets in understanding tourists’ pro-environmental behaviour. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC]. Climate Change 2018: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ukko, J.; Nasiri, M.; Saunila, M.; Rantala, T. Sustainability strategy as a moderator in the relationship between digital business strategy and financial performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, C. Sustainability (World Commission on Environment and Development Definition). In Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 2358–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinger, T. Environmental Sustainability—Definition and Issues—Economics Help. 2018. Available online: www.economicshelp.org/blog/143879/economics/environmentalsustainability-definition-and-issues/ (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Balundė, A.; Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. The Relationship Between People’s Environmental Considerations and Pro-environmental Behavior in Lithuania. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behaviour: Individual differences, leader behaviour, and co-worker advocacy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.; Liu, X. Pro-Environmental Behavior Research: Theoretical Progress and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, B.; Alvarez, M.D. Understanding the Tourists’ Perspective of Sustainability in Cultural Tourist Destinations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbrow, M. Visitors as advocates: A review of the relationship between participation in outdoor recreation and support for conservation and the environment. Sci. Conserv. 2019, 333. Available online: https://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/documents/science-and-technical/sfc333entire.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Yeh, S.S.; Guan, X.; Chiang, T.Y.; Ho, J.L.; Huan, T.C.T. Reinterpreting the theory of planned behaviour and its application to green hotel consumption intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. The role of social cognitive theory in sustainable hotel practices. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 283–302. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behavior—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aertsens, J.; Verbeke, W.; Mondelaers, K.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Personal determinants of organic food consumption: A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ru, X. Examining when and how perceived sustainability-related climate influences pro-environmental behaviours of tourism destination residents in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Donald, F.V. Developing an integrated conceptual framework of pro-environmental behavior in the workplace through synthesis of the current literature. Adm. Sci. 2014, 4, 276–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behaviour in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of consumers’ green purchase behavior in a developing nation: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, F.; Pattitoni, P.; Mura, M.; Strazzera, E. Predicting intention to improve household energy efficiency: The role of value-belief-norm theory, normative and informational influence, and specific attitude. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolske, K.S.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Explaining interest in adopting residential solar photovoltaic systems in the United States: Toward an integration of behavioural theories. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 25, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, C.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ perceptions and preferences for local food: A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tenkasi, R.V.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, J. Behavioural change in buying low carbon farm products in China: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2016, 8, 065902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mosquera, N.; Lera-López, F.; Sánchez, M. Key factors to explain recycling, car use and environmentally responsible purchase behaviours: A comparative perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 99, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riper, C.J.; Kyle, G.T. Understanding the internal processes of behavioural engagement in a national park: A latent variable path analysis of the value-belief-norm theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V. Dual ‘Realities’ of conservation Behavior: Self-reports vs. Observations of re-use and recycling behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 1997, 17, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Luzón, M.D.C.; García-Martínez, J.M.Á.; Calvo-Salguero, A.; Salinas, J.M. Comparative Study Between the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Value–Belief–Norm Model Regarding the Environment, on Spanish Housewives’ Recycling Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 2797–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepler, J.; Albarracín, D. Liking More Means Doing More: Dispositional Attitudes Predict Patterns of General Action. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 45, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Sustainable Tourism: Sustaining Tourism or Something More? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Weiler, B.; Smith, L.D.G. Place attachment, place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour: A comparative assessment of multiple regression and structural equation modelling. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2013, 5, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, A.; Maryati, S.; Pradono, P.; Purboyo, H. Sustainable transportation: The perspective of women community (a literature review). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 592, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, E.; Williams, K.J. Connectedness to nature, place attachment and conservation behaviour: Testing connectedness theory among farmers. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ville, N.V.; Tomasso, L.P.; Stoddard, O.P.; Wilt, G.E.; Horton, T.H.; Wolf, K.L.; Brymer, E.; Kahn, P.H., Jr.; James, P. Time spent in nature is associated with increased pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative explanations of helping behavior: A critique, proposal, and empirical test. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1973, 9, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Burnett, J. Impact of Waste Recycling Programs on Guest Participation in Hotels. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 937–945. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, E.S.W.; Lam, D. The Effects of an Energy-Saving Campaign on Energy Conservation Behavior in Hotels. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Boecker, A.; Maertz, C.P.; Maertz, C.P. Effects of Eco-Friendly Hotel Amenities on Guest Behavior: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 425–451. [Google Scholar]

- van der Weff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between bio-spheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Lee, M.J.; Chua, B.L.; Han, H. An integrated framework of behavioral reasoning theory, theory of planned behavior, moral norm and emotions for fostering hospitality/tourism employees’ sustainable behaviors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 4516–4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Understanding hotel guests’ pro-environmental behavior: The importance of NEP. Tour. Manag. 2019, 67, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E. The New Environmental Paradigm Scale: From marginality to worldwide use. J. Environ. Educ. 2008, 40, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Hotel customers’ pro-environmental decision-making process: The role of NEP. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zizka, L.; Dias, Á.; Ho, J.A.; Simpson, S.B.; Singal, M. From Extra to Extraordinary: An academic and practical exploration of Extraordinary (E) Pro Environmental Behavior (PEB) in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 119, 103704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “new environmental paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 2008, 40, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Chandra, B. Sustainability in hospitality: A study of energy conservation practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; De Groot, J.I.M.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W.; Siero, F. General antecedents of personal norms, policy acceptability, and intentions: The role of values, worldviews, and environmental concern. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2011, 24, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-environmental Behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Determinants of consumers purchase attitude and intention toward green hotel selection. J. China Tour. Res. 2020, 18, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Values, norms, and intrinsic motivation to act pro-environmentally. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Mean or green? Values, morality and pro-environmental behavior. Conserv. Lett. 2009, 2, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fittipaldi, S.; Legaz, A.; Maito, M.; Hernandez, H.; Altschuler, F.; Canziani, V.; Moguilner, S.; Gillan, C.M.; Castillo, J.; Lillo, P.; et al. Heterogeneous factors influence social cognition across diverse settings in brain health and age-related diseases. Nat. Ment. Health 2024, 2, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q. Socially responsible human resource management and hotel employee organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: A Social Cognitive Perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Hu, S.; Que, T.; Li, H.; Xing, H.; Li, H. Influences of social environment and psychological cognition on individuals’ behavioral intentions to reduce disaster risk in geological hazard-prone areas: An application of social cognitive theory. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 86, 103546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S.; Kim, W. Impact of hotel-guest engagement on pro-environmental behavior: Merging social cognitive theory and goal-directed behavior theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102352. [Google Scholar]

- Gerardo Barroso-Tanoira, F. Motivation for increasing creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship. an experience from the classroom to business firms. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 5, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.-E. The Influences of Social Intelligence on Cooperation and Individual Performance of Hotel Employees. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2016, 16, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mody, M.; Suess, C.; Lehto, X. The impact of social identity on environmental sustainability in the hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 245–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J. Social identity and sustainable practices: A study of customer loyalty in the hotel sector. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 43, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.-F.; Tung, P.-J. The role of social identity in the hotel sector: A case study of pro-environmental behaviors. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 675–692. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. Greenwashing perceptions and customer loyalty in the hotel industry: A social identity theory perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 52, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Rather, R.A.; Hollebeek, L.D. Exploring and validating social identification and social exchange-based drivers of hospitality customer loyalty. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1432–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M.; Lohmann, S.; Albarracín, D. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes, Volume 1: Basic Principles; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 197–255. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Attitudes towards objects as predictors of single and multiple behavioral criteria. Psychol. Rev. 1974, 81, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-M.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, C.-K. Predicting hotel guests’ recycling behavior using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Tour. Manag. 2023, 40, 245–257. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Yoon, Y. Examining the role of TPB in promoting sustainable energy practices in hotels. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 120–135. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.-F.; Hsu, C.-H.; Chen, T.-L. Enhancing guest participation in hotel green practices: A TPB approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 60, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, S. The effectiveness of TPB-based interventions in the hotel industry: A meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 382–399. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S.W., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Acampora, A.; Preziosi, M.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Merli, R. The role of Hotel Environmental Communication and guests’ environmental concern in determining guests’ behavioral intentions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.K.; Chang, Y.J.; Chang, I.C.; Yu, T.Y. A pro-environmental behavior model for investigating the roles of social norm, risk perception, and place attachment on adaptation strategies of climate change. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 25178–25189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, H.; Yayla, O.; Tarinc, A.; Keles, A. The effect of environmental management practices and knowledge in strengthening responsible behavior: The moderator role of environmental commitment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, A. Studying the Impact of Environmental Consciousness on Perceived Effectiveness of Eco-Friendly Products in Delhi NCR. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, C.; Liu, C. Study on the influencing factors of public participation in environmental protection. J. Zhengzhou Univ. 2017, 50, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Han, H. Intention to pay conventional hotel prices at a green hotel–a modification of the theory of planned behaviour. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, W. Impact of social/personal norms and willingness to sacrifice on young vacationers’ pro-environmental intentions for waste reduction and recycling. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2117–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untaru, E.N.; Ispas, A.; Candrea, A.N.; Luca, M.; Epuran, G. Predictors of individuals’ intention to conserve water in a lodging context: The application of an extended theory of reasoned action. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 59, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M. Examining the effectiveness of environmental messages on hotel guests’ green behaviours: The role of normative influence. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 844–860. [Google Scholar]

- Anton, D.F. Characteristics of the ‘ecological consciousness’ concept: Content and definition within the framework of an interdisciplinary method. Alma Mater Vestn. Vyss. Shkoly 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Težak Damijanić, A.; Pičuljan, M.; Goreta Ban, S. The role of pro-environmental behavior, environmental knowledge, and eco-labeling perception in relation to travel intention in the hotel industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.W.; Hon, A.H.Y.; Okumus, F.; Chan, W. An empirical study of environmental practices and employee ecological behaviour in the hotel industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 170–179. [Google Scholar]

- Tavitiyaman, P.; Zhang, X.; Chan, H.M. Impact of environmental awareness and knowledge on purchase intention of an eco-friendly hotel: Mediating role of habits and Attitudes. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Fyall, A.; Baker, C. Sustainable labels in Tourism Practice: The effects of sustainable hotel badges on guests’ attitudes and behavioral intentions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empidi, A.V.A.; Emang, D. Understanding public intentions to participate in protection initiatives for forested watershed areas using the theory of planned behavior: A case study of Cameron Highlands in Pahang, Malaysia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Peng, X. Can the home experience in luxury hotels promote pro-environmental behavior among guests? PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asante, K.B. Hotels’ green leadership and employee pro-environmental behaviour, the role of value congruence and moral consciousness: Evidence from symmetrical and asymmetrical approaches. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 32, 1370–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapera, R.; Mbongwe, B.; Mhaka-Mutepfa, M.; Lord, A.; Phaladze, N.A.; Zetola, N.M. The theory of planned behavior as a behavior change model for tobacco control strategies among adolescents in Botswana. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice-Hall Publication: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Han, T.I. Objective knowledge, subjective knowledge, and prior experience of organic cotton apparel. Fash. Text. 2019, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Driver, B.L. Application of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice. J. Leis. Res. 1992, 24, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D.R.; Schindler, P.S. Business Research Methods, 12th ed.; McGraw Hill International Edition: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- CSO—Central Statistics Office, Mauritius. Yearly Digest of International Travel and Tourism. 2022. Available online: https://statsmauritius.govmu.org/ (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L. Sampling in developmental science: Situations, shortcomings, solutions, and standards. Dev. Rev. 2013, 33, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, L. Why environmental sustainability is important. BDJ Pract. 2021, 34, 40–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vught, F.; Huisman, J. Institutional profiles: Some strategic tools. Tuning J. High. Educ. 2014, 1, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.F.; Charry, A.; Sellitti, S.; Ruzzante, M.; Enciso, K.; Burkart, S. Psychological Factors Influencing Pro-environmental Behavior in Developing Countries: Evidence From Colombian and Nicaraguan Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 580730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; van der, W.E.; Bouman, T.; Harder, M.K.; Steg, L. I am vs. we are: How biospheric values and environmental identity of individuals and groups can influence pro-environmental behaviour. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 8956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods and Practices; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Sun, W.; Lu, C.; Chen, W.; Guo, V.Y. Adverse childhood experiences and handgrip strength among middle-aged and older adults: A cross-sectional study in China. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Ertz, M.; Sarigollu, E. The behavior-attitude relationship and satisfaction in pro environmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 1106–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namagembe, S. Climate change mitigation readiness in the transport sector: A psychological science perspective. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2021, 32, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, C.R.; Kalantari, H.; Johnson, L.W. Climate change beliefs, personal environmental norms and environmentally conscious behaviour intention. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.Y.; Amirudin, A.; Rahadi, R.A.; Nik Sarah Athirah, N.A.; Ramayah, T.; Muhammad, Z.; Dal Mas, F.; Massaro, M.; Saputra, J.; Mokhlis, S. An Investigation of Pro- Environmental Behaviour and Sustainable Development in Malaysia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, M.E.; Ferrer, D.M.; Mu~noz, L.V.A.; Claros, F.M.; Ruiz, F.J. University as change manager of attitudes towards environment (the importance of environmental education). Sustainability 2020, 12, 4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, E.; De Guimarães, J.; Dellarmelin, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on environmental awareness, sustainable consumption and social responsibility: Evidence from generations in Brazil and Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 124947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ootegem, L.V.; Verhofstadt, E.; Defloor, B.; Bleys, B. The Effect of COVID-19 on the Environmental Impact of Our Lifestyles and on Environmental Concern. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Patchen, M. Public Attitudes and Behavior about Climate Change: What Shapes Them and How to Influence Them; University of Purdue: East Lafayette, Indiana, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sürücü, L.; Maslakci, A. Validity and reliability in quantitative research. Bus. Manag. Stud. Int. J. 2020, 8, 2694–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research. Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 10th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C. Real World Research: A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods in Applied Settings, 2nd ed.; Sussex, A., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oluwatayo, J.A. Student Rating of Teaching Behaviour of Chemistry Teachers in Public Secondary Schools in Ekiti State. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 2013, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Doss, C.R.; Morris, M.L. How does gender affect the adoption of agricultural innovations? Agric. Econ. 2001, 25, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fransson, N.; Gärling, T. Environmental concern: Conceptual definitions, measurement methods, and research findings. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Gutscher, H. The proposition of a general version of the theory of planned behavior: Predicting ecological behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 586–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellish, S.; Pearson, E.L.; McLeod, E.M.; Tuckey, M.R.; Ryan, J.C. What goes up must come down: An evaluation of a zoo conservation-education program for balloon litter on visitor understanding, attitudes, and behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1393–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, S. Social norms and their influence on eating behaviours. Appetite 2015, 86, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.; Vostroknutov, A. Why do people follow social norms? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkargkavouzi, A.; Halkos, G.; Matsiori, S. A multi-dimensional measure of environmental behavior: Exploring the predictive power of connectedness to nature, ecological worldview and environmental concern. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 143, 859–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Zarkada, A.; Ramayah, T. The impact of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control on managers’ intentions to behave ethically. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2018, 29, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Ma, Y.; Ren, J. Influencing factors and mechanism of tourists’ pro-environmental behavior—Empirical analysis of the CAC-moa integration model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1060404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors?: The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulphey, M.M.; Faisal, S. Connectedness to nature and environmental concern as antecedents of commitment to environmental sustainability. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2021, 11, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Hübner, G.; Bogner, F. Contrasting the theory of planned behaviour with the value-belief-norm model in explaining conservation behaviour. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 2150–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Sharma, R. Determinants of pro-environmental behavior and environmentally conscious consumer behavior: An empirical investigation from emerging market. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2020, 3, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.V.; Young, C.W.; Unsworth, K.L.; Robinson, C. Bringing habits and emotions into food waste behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyaningtyas, D.; Untoro, W.; Setiawan, A.I.; Wahyudi, L. Health awareness determines the consumer purchase intention towards herbal products and risk as moderator. Contaduría Adm. 2023, 68, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Griffiths, M.A. Share more, drive less: Millennials value perception and behavioral intent in using collaborative consumption services. J. Consum. Mark. 2017, 34, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.K.; Lin, F.Y.; Kao, K.Y.; Yu, T.Y. Encouraging Environmental Commitment to Sustainability: An Empirical Study of Environmental Connectedness Theory to Undergraduate Students. Sustainability 2019, 11, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivis, A.; Sheeran, P. Descriptive norms as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2003, 22, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chi, C.G. Environmental sustainability in the hotel industry: A literature review. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 397–409. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S. Eliciting customer green decisions related to water saving at hotels: Impact of customer characteristics. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1437–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Koo, D.W.; Han, H.S. Innovative behavior motivations among frontline employees: The mediating role of knowledge management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lee, K. Environmental consciousness, purchase intention, and actual purchase behavior of eco-friendly products: The moderating impact of situational context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.S.; Shih, L.H. Effective environmental management through environmental knowledge management. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 6, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviour. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, A.; Yang, S.; Iqbal, Q. Factors affecting purchase intentions in generation Y: An empirical evidence from fast food industry in Malaysia. Adm. Sci. 2018, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability. Development, Globalisation and New Tourism in the Third World, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable Tourism: Research and Reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H.; Kühling, J. Are pro-environmental consumption choices utility-maximizing? Evidence from subjective well-being data. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 72, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchs, M.; Schnepf, S. Who Emits Most? Associations between Socio-Economic Factors and U.K. Households’ Home Energy, Transport, Indirect and Total CO2 Emissions. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 90, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas, L. Moving Toward Greener Societies: Moral Motivation and Green Behaviour. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2018, 70, 835–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenberg, A.; Alhusen, H. On the Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Literature Review and Guide for the Empirical Economist; CEGE Discussion Papers, No. 350; University of Göttingen, Center for European, Governance and Economic Development Research: Göttingen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Theoretical Model | Main Variables/Themes | Comparison to TPB |

|---|---|---|

| Norm Activation Model (NAM) | Awareness of Consequences (AC) Ascription of Responsibility (AR) Personal Norms (PN) | NAM emphasises morality through personal norms and perceived consequences. In contrast, TPB emphasizes attitudes, subjective standards, and perceived behavioral control. Although both examine subjective impacts, NAM emphasizes moral and ethical factors. |

| New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) | Environmental Concern Beliefs about Environmental Issues Ecological Worldview | NEP focuses on environmental attitudes and worldviews that affect environmental concern. TPB emphasizes behavioral attitudes rather than environmental views. TPB prioritizes behavior-specific goals over worldviews. |

| Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) Theory | Values Beliefs Norms Norm Activation (similar to NAM) | The VBN model integrates values and beliefs, which correspond to the TPB’s emphasis on attitudes. The inclusion of values in VBN serves to create a comprehensive framework for comprehending motivation, while TPB is more focused on behavioral intentions. Although Value-Based Networks (VBN) integrate values and beliefs, both prioritize norms. |

| Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) | Observational Learning Self-Efficacy Outcome Expectations Reciprocal Determinism | Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) places significant emphasis on self-efficacy and observational learning, specifically examining how individuals acquire knowledge from their surroundings and develop confidence in carrying out certain actions. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) similarly takes into account behavioral control, although it places less emphasis on observational learning or reciprocal determinism. |

| Social Identity Theory (SIT) | Social Categorization Social Identification Social Comparison In-group and Out-group Dynamics | Social Identity Theory (SIT) concentrates on the intricate relationship between group dynamics and social identity, which shape behavior by means of group norms and identity. TPB primarily examines individual-level attitudes and perceived control, while Social Identity Theory (SIT) highlights the influence of group membership and social identity on behavior. |

| Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) | Attitudes Subjective Norms Perceived Behavioral Control Behavioral Intentions | (TPB) is characterized by its emphasis on intentions as a direct antecedent to conduct. Attitudes, subjective standards, and perceived behavioral capability exert influence on these intentions. In contrast to other theories that may emphasize particular motivational elements or environmental beliefs, this theory has a wider scope of application to diverse behaviors. |

| Hypotheses | Relationships Determined in the Conceptual Framework |

|---|---|

| H1 | Behavioral Beliefs → Attitude |

| H2 | Normative Beliefs → Subjective Norms |

| H3 | Control Beliefs → Perceived Behavioral Control |

| H4 | Environmental Concern → Attitude |

| H5 | Environmental Commitment → Attitude |

| H6 | Environmental Consciousness → Attitude |

| H7 | Environmental Knowledge → Attitude |

| H8 | Environmental Knowledge → Behavioral Intention |

| H9 | Attitude → Behavioral Intention |

| H10 | Environmental Knowledge → Perceived Behavioral Control |

| H11 | Behavioral Intention → Perceived Behavioral Control |

| H12 | Subjective Norms → Behavioral Intention |

| H13 | Behavioral Intention → Actual Behavior |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 3.45 | 0.98 |

| Behavioral Intention | 3.67 | 1.02 |

| Subjective Norms | 3.25 | 0.85 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 3.50 | 0.90 |

| Environmental Knowledge | 3.80 | 1.05 |

| Construct | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|

| Attitude | 0.85 |

| Behavioral Intention | 0.87 |

| Subjective Norms | 0.82 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.84 |

| Environmental Knowledge | 0.88 |

| Predictor | Beta | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 0.30 | 4.25 | <0.01 |

| Subjective Norms | 0.25 | 3.80 | <0.01 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.28 | 4.00 | <0.01 |

| Environmental Knowledge | 0.32 | 4.50 | <0.01 |

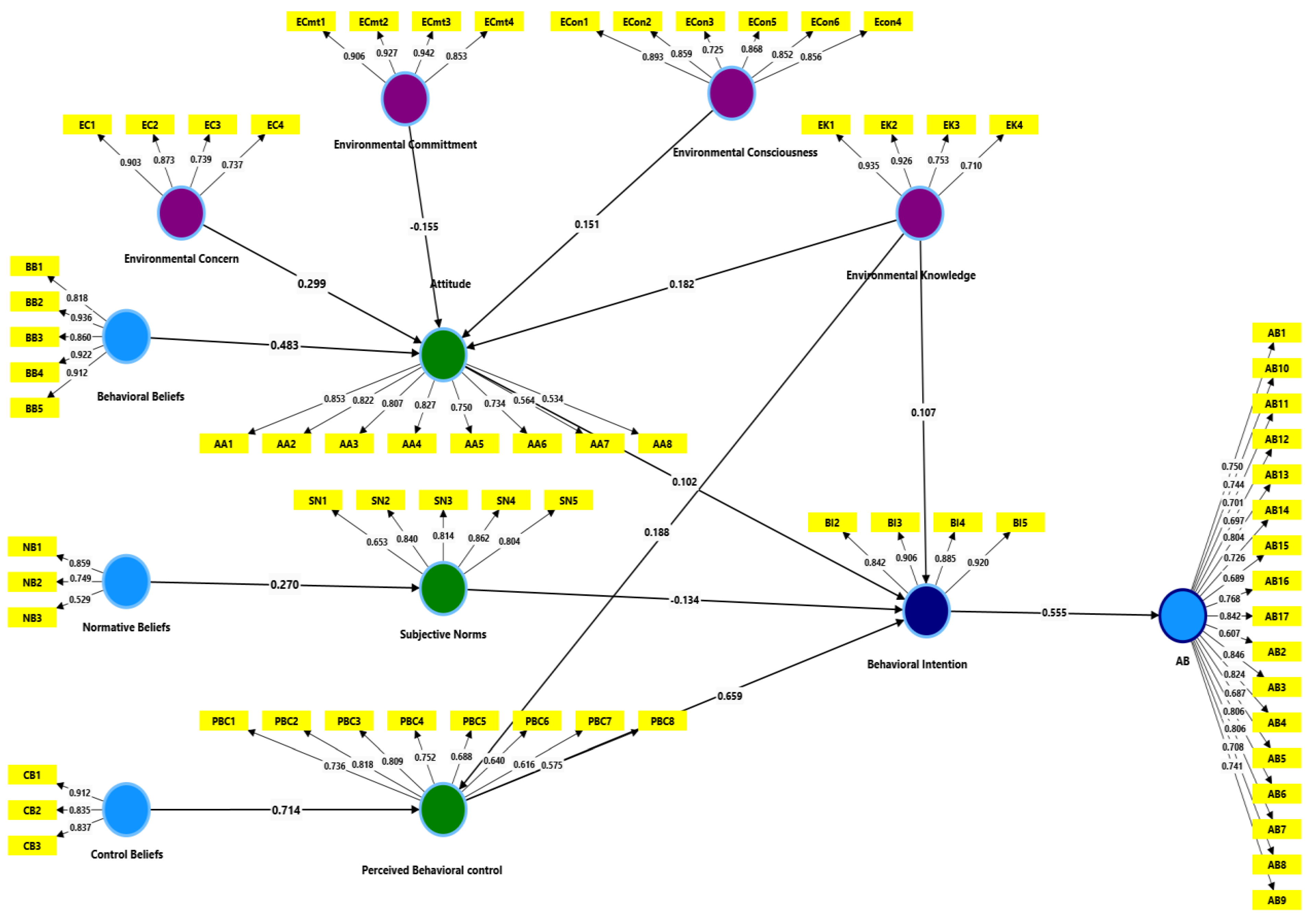

| Hypothesis | β-Value | t-Value | p-Values | CI (LL) | CI(UL) | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | BB → ATT | 0.484 | 8.847 | 0.000 | 0.374 | 0.581 | Supported |

| H2 | NB → SN | 0.270 | 3.563 | 0.000 | 0.145 | 0.415 | Supported |

| H3 | CB→ PBC | 0.783 | 27.88 | 0.011 | 0.722 | 0.834 | Supported |

| H4 | EC → ATT | 0.299 | 6.190 | 0.000 | 0.201 | 0.394 | Supported |

| H5 | ECmt → ATT | −0.15 | 2.544 | 0.000 | −0.259 | −0.015 | Not supported |

| H6 | ECon → ATT | 0.151 | 2.001 | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.303 | Supported |

| H7 | EK → ATT | 0.182 | 2631 | 0.000 | 0.045 | 0.317 | Supported |

| H8 | EK → BI | 0.137 | 2.715 | 0.000 | 0.034 | 0.234 | Supported |

| H9 | ATT → B1 | 0.120 | 1.841 | 0.066 | 0.003 | 0.249 | Supported |

| H10 | EK → PBC | 0.188 | 0.188 | 0.055 | 3.442 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H11 | PBC → BI | 0.654 | 10.323 | 0.000 | 0.518 | 0.766 | Supported |

| H12 | SN → BI | −0.15 | 2.683 | 0.007 | −0.250 | −0.041 | Not supported |

| H13 | BI → AB | 0.551 | 9.613 | 0.000 | 0.441 | 0.665 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makoondlall-Chadee, T.; Bokhoree, C. Understanding the Influencing Factors of Pro-Environmental Behavior in the Hotel Sector of Mauritius Island. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 5, 942-976. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5040054

Makoondlall-Chadee T, Bokhoree C. Understanding the Influencing Factors of Pro-Environmental Behavior in the Hotel Sector of Mauritius Island. Tourism and Hospitality. 2024; 5(4):942-976. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5040054

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakoondlall-Chadee, Toshima, and Chandradeo Bokhoree. 2024. "Understanding the Influencing Factors of Pro-Environmental Behavior in the Hotel Sector of Mauritius Island" Tourism and Hospitality 5, no. 4: 942-976. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5040054

APA StyleMakoondlall-Chadee, T., & Bokhoree, C. (2024). Understanding the Influencing Factors of Pro-Environmental Behavior in the Hotel Sector of Mauritius Island. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(4), 942-976. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5040054