1. Introduction

Sport events are an important part of human life. They are attended by both active players and passive fans. A sport event is characterized by sport content, a large number of participants, and accompanying entertainment programs [

1]. In terms of the importance of an event, its size and scope of impact are very important. Getz and Page [

2] accurately describe this phenomenon by dividing events into occasional mega-events, periodic hallmark events, regional events, and local events. A similar division assumes the occurrence of local events, large events, events of symbolic importance, and mega-events [

3]. Typically, the larger the event (and often the less frequently it takes place), the more participants it attracts.

According to Bowdin et al. [

4], sport events can be divided into several categories depending on their size and importance. Mega-events are very large events that attract many competitors and spectators and have a global reach. Calendar events are based mainly on previously built reputation and tradition, and they are based on the international calendar of events for a particular sport discipline. One-off events are characterized by great interest among the media and fans. The place for such an event is selected as a result of a tender. Showcase events are usually regional events involving local people, which can influence the way other people perceive a given country or city, as well as the development of a given sport discipline.

Sport events are most often competitive and entertaining in nature, and also serve to promote various forms of physical activity based on the principles of fair play [

5]. Such events trigger many emotions that are independent of passive or active participation [

6]. Sport events build well-being and a sense of happiness. Well-being can come from many sources, such as the pleasure of attending events, being involved, and the joy of being close to events even if one is not participating in them [

7]. Due to their specific nature, sport events require particularly good organization. Hosts see significant benefits from organizing sport events. They link the benefits of sporting events to political, social, economic, physical, cultural, and environmental impacts. Such events have the ability to regenerate areas and create jobs both during and before the event. Sometimes sport events require the creation or renovation of infrastructure to accommodate large numbers of visitors [

8]. It is worth emphasizing that rural centers with a weaker economy usually record significant financial benefits from organizing sport events. Even small sport events also play an important role in building and promoting the image of rural areas. Holding small sport events in rural destinations provides an opportunity to offer forms of sustainable tourism in rural areas [

9,

10,

11].

Creating a sport event requires focusing on many criteria and elements. One such element is the atmosphere of the event, understood in the most general sense as the character, feeling, or mood of a place and situation [

12]. In this context, research on the atmosphere of sport events appears quite rarely in the literature. Researchers refer more often to stadium atmosphere e.g., [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Meanwhile, Kaplanidou et al. [

17] emphasize that the positive atmosphere of the destination and event favors participants’ willingness to return to the place and the event. Dankowska [

18] points out that creating a sport event requires focusing on the participants, the place where the event is organized, as well as the scope of the program and content of the event. Broadly understood, the atmosphere of a sport event, which includes various event attributes, influences the quality of event management. According to Kelley and Turley [

19], such attributes include the competition, the participants, and the place.

A good atmosphere is enough to ensure customer satisfaction and loyalty. Additionally, atmosphere influences public perception of sport events [

13]. According to the results of Kement et al. [

20], a good atmosphere affects willingness to return to a place, to recommend the place to others, and also to spend more money. In pursuance of the authors, the impact of atmosphere on customer decisions requires further and broader research and more detailed models. In the field of local sport events, Wafi et al. [

21] indicate a research gap in measuring how the perception of an event influences visitors’ decisions to attend. In this respect, there is a research gap regarding the participants’ assessment of the atmosphere of the event and its components. Hence, the main aim of this article is to assess the impact of rural sport event atmosphere on participants. The research consists of the following research questions:

Q1. How do participants perceive the atmosphere of the rural sport event?

Q2. What are the most important components of the atmosphere for participants?

Research was conducted during the Commando Quarter Marathon on 22 January 2022. The race is a cyclical event, held annually in the rural areas of Słupsk in Poland. Participants run a distance of 10.55 km in full uniform. The aim of the race is to popularize running and a healthy lifestyle through active participation in the event.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 provides a literature review;

Section 3 contains research hypothesis;

Section 4 refers to Materials and Method; and

Section 5 contains Study context and research samples. The results are presented in

Section 6 and supported by discussion in

Section 7. The article ends with conclusions in

Section 8.

2. Sport Event Atmosphere Components—Theoretical Background

The conducted literature review of the components of sport event atmosphere concerns a race for active participants without taking into account spectators, i.e., passive participants. According to the definition, sport events can belong to a group of events in which there is a clear distinction between active participants and passive participants, or to a group of participatory events in which sportsmen (often amateurs) play, but wherein they also constitute a significant part of the audience. Different components influence the perception of a sport event by active participants compared to passive participants. In general, the way a sport event’s atmosphere is determined is through factors related to the primary offering (resulting from the location of the hosting area, its attractiveness) and factors related to the secondary offering (equipment, infrastructure, service, information, gastronomy, etc.) [

1]. It is worth adding that sport event atmosphere does not focus on elements popular in other areas of tourism and recreation to create experiences, such as scent, lighting or sound.

Taking into account the views of Dankowska [

18] and Kelley and Turley [

19], sport event atmosphere from the participants’ perspectives was divided into three groups of components: event organization, relationships between participants, and event place. In relation to event organization, rules and safety, event management, hosting, and sport competition class were distinguished. The scope of other participants included: integration, sharing passion, and ability to compete. Within the place, the elements were divided into attractiveness of the area, attractiveness of the sport competition place, and the willingness to return to the place.

2.1. Event Organization

A sport event’s atmosphere should be a priority for organizers, as it can determine the satisfaction of participants, as well as the local community [

13]. Ryan and Lockyer [

22] emphasize that the organizational aspects of sport events are particularly important for experienced competitors, many of whom have traveled to take part in them. Aspects such as disorganization and lack of signage are perceived as particularly discouraging. An important recommendation for all event managers is to pay attention to the details of event organization. Participants expect good signage and a general sense of efficiency.

In their research, Chersulich et al. [

23] point out the importance of the safety of a sport event. Security is not only a destination element, but also a strategic event attribute. According to Cleland [

24], risk is present in the minds of a significant number of people associated with sporting events, which leads to the development of more aversive behaviors. The author emphasizes that although there is a need to manage risk during sporting events, it should not be at the expense of creating a sense of fear among participants. Maintaining safety covers many areas of event management and there are different levels of stakeholder involvement. Stakeholders should ensure that they do not limit their perspective only to security and terrorism but take into account all aspects of risk in event planning and preparation [

25]. Poczta et al. [

26] add that the organization and safety of a sport event should also include locals who involuntarily become its participants. It should be remembered that a sport event is associated not only with benefits, but also with negative effects, such as high costs of organization, crowds, difficulties in the normal functioning of premises, noise, and environmental hazards. Organizers must take these factors into account.

However, event hosts must remember that participants expect competent service and punctuality in starting events on time. Active sport tourists are quite a demanding group [

27]. Service quality and satisfaction play a very important role in determining success in sport management. Participant satisfaction is a key factor in the organization of sport events because it is the main driver of future behavior [

28]. Satisfaction is therefore a focal point of sport management and research because satisfaction is a consequence of service quality, which is a manageable antecedent of future intentions [

29]. This is important because hosting cyclical sport events can be a solution for the sustainable development of tourism, resulting in loyalty to destinations and a higher level of attachment to places [

17].

Generally, hosting sport events can bring many economic, social, and environmental benefits. The economic ones include investments, renovation, modernization of existing facilities, and tourism development by creating a positive image of the place. In the social dimension, organizing an event gives the local community an opportunity to work towards a common goal. Additionally, sport events can provide funding for environmental projects [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

The rank of the sport event is usually more important for professional competitors. For sport enthusiasts, the opportunity to participate is usually more important. For professionals, professions are associated with the need to achieve results and be successful, as these are important determinants in their careers [

35].

2.2. Relationships between Participants

In relation to the participants of a sport event, important factors include integration, sharing passion, and competition. Sport undoubtedly brings people together. Sport—in various forms—contributes to building relationships and interactions between people [

36]. Organized as well as spontaneous sport offers many benefits in terms of social integration. Encouraging contact with other people, it provides an opportunity to learn and consolidate social skills, including conflict resolution [

37]. For participants, sport events offer a specific atmosphere. Through interaction with other people, personal values can be created, satisfying individual needs. It is worth adding that active involvement makes experiences and values diverse and personal [

38].

Sport is a global movement with a common language. As a global phenomenon, it is an important arena for the integration of societies [

39]. Sport events can contribute to multicultural social integration. In this respect, a sport event creates a space for participants. In this space, participants can achieve results that reflect their own interests. It should be emphasized, however, that the social effects of participation in a sport event usually first reflect the participant’s own interests [

40]. Despite the predominance of individual interests, sport events are an opportunity to build broadly understood social capital. This happens due to the participation of many people who have a common goal and passion, or simply spend time together [

41].

Passion is an important element of sport. Various aspects of it are noticed, hence the division into harmonious and obsessive passion [

42], which are part of the dualistic model of passion. According to this model, passion is a strong inclination towards a self-defining activity that people like, value, and consider important, and in which they invest a significant amount of time and energy. Harmonious passion is characterized by a strong desire to engage freely in a passionate activity. Obsessive passion, on the other hand, overwhelms attention and is associated with excessive control [

43,

44]. Harmonious passion has a direct impact on athletes’ future intentions, perceived value, and satisfaction, while obsessive passion has a direct impact mainly on athletes’ satisfaction [

29].

Overall, passion for sport is positively associated with psychological needs and motivation. Importantly, passion affects the sense of competence and autonomy in participating in sport, as well as positive relationships with other players [

45], hence the participants’ desire to share their passion with other people. In this approach, passion can be treated as an element of the exchange process, e.g., between players and fans [

46]. This exchange may also include participant–participant relationships in a sport event. Kim et al. [

47] observed that the passion of other participants is an important determinant of value perception (both social and economic). Therefore, passion can be shared with other people.

One of the important elements of sport event atmosphere is competition and the opportunity to test abilities against other participants. Kelley and Turley [

19], examining the attributes of the quality of service for sport events, emphasize that this quality is also created by the sport competition itself. It is worth adding that sport competition is important not only for sport players, but also for passively watching fans [

48]. Moreover, Gommon and Robinson [

49] emphasize that competition is the basis not only of sport, but also of sport tourism, which includes traveling outside one’s usual environment to practice passive and active sports. Excitement represents the degree to which a sport event is perceived as providing stimulation. Individuals are motivated to seek out experiences from a sport event because of the opportunities to act and explore from the conditions created by the uncertainty of participation and competition and the spectacle of the activities involved [

50]. An interesting approach to competition is presented by Hayek [

51], according to which it is related to the discovery of facts. In the case of sport events, it is not known who the winner will be, and this element of surprise contributes to building an atmosphere of uniqueness. It is worth adding that sport brings people together and creates an opportunity for significant social interactions. Therefore, involvement and competition play a role in creating social capital [

36,

52]. It should be emphasized that many approaches to sport management derived from economic theory characterize sport competition as a team production process, focusing on results, limiting value creation to the production process and limiting sport consumers to the role of buyers [

53].

2.3. Event Place

A good place to organize a sport event must have a number of features. The destination must provide appropriate infrastructure and opportunities to create, promote, and organize tourist attractions, expand media coverage, and strengthen cooperation between national, regional, and local tourism organizations [

54].

A sport event can attract new guests who would not otherwise come to a given place. Therefore, thanks to sport events, a new group of tourists can be created [

55]. This means that the organization of sport events can contribute to increasing the attractiveness of these tourist destinations [

56]. Therefore, the attractiveness of a place in terms of sport events can be understood in two ways. Firstly, an attractive event location may be an attraction factor. Secondly, a sport event can increase the attractiveness of a given place.

When choosing a place to organize events, it is worth remembering environmental resources. These resources include the host’s local attractions, including landscape and cultural heritage (local culture and traditions). Environmental resources can contribute to the success of an event, if used appropriately [

57].

Outdoor events are highly location dependent, as the natural landscape and cultural heritage of the host city provide a unique setting that is key to experiencing the event [

58]. Space and place play a key role in the geography of sport tourism. Sports have features that are fixed spatial parameters such as time and dimensions. The event place is separated from the space as it gains significance [

55,

59]. In the field of outdoor events, rural areas are often a good location due to the space, environment and landscape. Such conditions are required by, among others: bicycle, motorcycle and running sports [

11,

60,

61].

Among outdoor sports, running is particularly popular. Running is a place-based sport, wherein the runner interacts with the landscape. The attractiveness of a running route is quite important for runners [

60]. However, it should be emphasized that this is more important for hobby runners. Among this group, an attractive landscape can even be a decisive factor in choosing a tourist destination for running. Another important factor is the ground, which is especially important for runners [

62,

63,

64]. In relation to running, the importance and suitability of a place is characterized by specific spatial guidelines (e.g., length of the run, difficulty of the route) [

58].

Threats are also indicated regarding the attractiveness of the running route. The most common difficulties encountered on running routes are poor lighting, off-leash dogs, and encounters with cyclists and cars [

64]. Therefore, the safety of runners is also important when it comes to running routes at sporting events.

Atmosphere is important because it can affect willingness to return to a place. This is an important determinant that should be taken into account by place and event managers. This is part of the process of attachment to place, which is extremely important in the hospitality sector [

20,

65]. Some participants express their desire to return to the event venue. This is a kind of loyalty. It is generated primarily as a result of satisfaction with the event, commitment, good organization, and victories (this applies not only to players, but also to fans taking part in the sport event) [

66]. The place dependence component has a more functional meaning, being more related to the physical attributes of a place and their ability to meet the goals and expectations of visitors [

67]. Cardinale et al. [

68] state that place loyalty is emotional. This is confirmed by the results of Kaplanidou et al.’s [

17] research, which indicates the important role of the atmosphere of a destination, the cultural context, and the characteristics of the event in increasing the level of dimensions of attachment to a place, identity.

Tzetzis et al. [

69] confirmed the hypothesis that participation outcomes motivate active sport tourists to interact with the environment and facilitate the development of their attachment to the environment, which in turn will influence their intention to return to the destination. Among sport tourists, the willingness to return is related to the quality of services and the level of satisfaction [

70,

71]. Satisfaction is a driving variable of positive attitude and re-attendance intentions, while destination image plays a strong complementary role in re-attendance intentions [

27]. Hallmann et al. also point out the importance of the image of a place in terms of a sport tourist’s willingness to return [

72].

Among sport tourists, important factors influencing willingness to visit again are sport facilities and activities, personal safety, friendliness of the locals, a clean and green city, tourist information, and support. Moreover, sport tourists rate the functioning of sport facilities, activities, and accommodation facilities higher than non-sport tourists [

54]. According to Hung et al. [

73] both creative experiences and the memorability of the experienced activity will have a significant positive relationship with revisit intention. Newland and Jung-Eun Yoo [

74] point out the need to examine how well event organizers understand the interests of their participants in the destination, its tourist advantages, and other event offers.

3. Research Hypothesis

As a part of the research, three research hypotheses were tested. According to Kement et al.’s [

20] research, atmosphere is an important factor influencing both current and future consumer behavior. It should be emphasized that this influence is positive. Taking into account the statement by Kelley and Turley [

19] that the main factors building the quality of event management are the athletics competitions themselves, their place, as well as the other people participating in the event, the first research hypothesis was formulated:

H1. The atmosphere is a key element of the sport event.

Due to the fact that preferences for participating in a sport event usually first reflect participants’ own interests [

42] the second research hypothesis was assumed:

H2. For participants, the organization of the sport event and its place are more important than relationships with other participants.

As Ryan and Lockyer [

22] emphasize, this results from the fact that participants expect good management, safety, and an appropriate place. Safety is one of the most important determinants of a good sport event [

23,

24,

25,

26]. The place where the event is organized is also related to a sense of security and good management. This is especially important in the case of a running event, where, in addition to the rules, an appropriate route is needed depending on the race, e.g., suitably difficult, but at the same time safe [

55,

59]. These factors build satisfaction with the event. Taking into account the fact that satisfaction and a good atmosphere are factors that determine the willingness to return [

19,

70] the third research hypothesis was formulated:

H3. Satisfaction with a running event has a positive impact on the perception of the event and its atmosphere components.

Satisfaction from participating in an event may not only influence its positive perception, but also, going further, may influence the limited perception of shortcomings and mistakes related to the organization of the event. A good event atmosphere promotes participant satisfaction, which is why it is such an important factor in building an event, by supporting good organization [

15]. In general, it should be emphasized that the determinants of an event’s atmosphere are interconnected and complement each other. However, they cannot be mutual substitutes. They are characterized by a synergistic, but not substitutive, effect.

4. Materials and Methods

The study design includes several stages: (1) literature review—identifying the components of a sport event atmosphere; (2) building a questionnaire for data collection; (3) conducting the survey; (4) statistical compilation of data; and (5) description and discussion of results. The research was conducted using the IPA model (Importance–Performance Analysis). This model is used in qualitative research regarding perception and satisfaction with certain processes, phenomena, and products. The IPA model aims to compare the expectations and assessment of respondents as to the actual state of affairs regarding the offered product. It is assumed that respondents’ preferences are a function of their assessments of the features of the phenomenon under study [

75,

76]. On 22 January 2022, 127 respondents assessed the atmosphere—before the run defining “importance” and after the run defining “performance”. The study was carried out using a questionnaire consisting of two main parts: the importance scale (the respondent subjectively assesses the value of the researched process) and the performance scale (the respondent assesses the level of implementation of the researched process). Therefore, the respondent’s ideas are compared with the real situation. A five-point Likert scale was used for evaluation [

77,

78]. Based on the literature review, the following elements of event atmosphere were analyzed: event organization — rules and safety, event management and hosting, class of the run; relationships between participants — integration, sharing passion, ability to compete; event place— attractiveness of the area, attractiveness of the route, the will to return to the place.

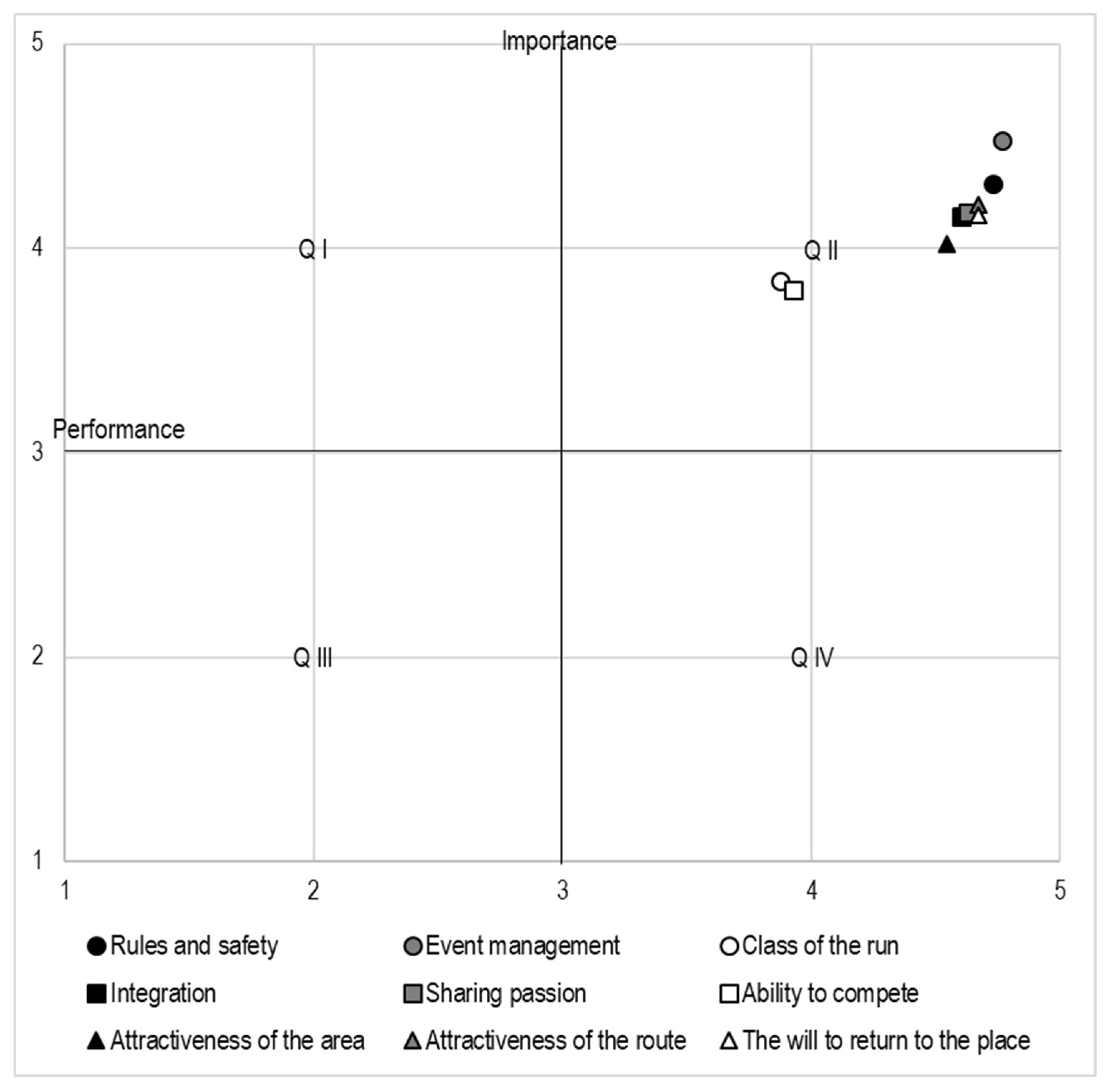

The next step in the research procedure was to place the obtained results on a chart, where one of the axes indicates the degree of importance and the other the scale of implementation. The axes form four quadrants [

79,

80,

81]:

Quadrant I (High Importance/Low Performance) is labeled “Concentrate Here”. Features in this quadrant represent key areas that require improvement with the highest priority.

Quadrant II (high importance/high performance) is labeled “Keep Up the Good Work”. All the characteristics that belong to this quadrant are strength and pillar and do not require change.

Quadrant III (Low Importance/Low Performance) is labeled “Low Priority”. Features that fall into this quadrant are not important and do not require a high degree of implementation.

Quadrant IV (Low Importance/High Performance) is labeled “Possible Overkill”. Means features that are assessed by respondents as not very important, but are characterized by an excessive level of implementation; one should consider whether it is worth focusing on these features or allocating more resources to features in quadrant I.

As a part of the research, respondents completed two paper forms. They filled out the first form before the run, commenting on the “importance” of the atmosphere of the event. After the run, the tested group completed the second form relating to “performance”. Both forms contained the same categories, which respondents rated using a five-point Likert scale.

5. Study Context and Research Sample

The research was conducted during the Commando Quarter Marathon. It is a cyclical sport event organized every year in rural areas near Słupsk (city in Poland). The eighth Commando Quarter Marathon was planned for 22 January 2022 in the buffer zone of the “Słupia Valley” Landscape Park. The aim of this cyclical sport event is to popularize running as the simplest form of physical recreation, promote a healthy lifestyle, enable competitors to compete in extreme conditions, popularize competition between uniformed services, and prepare participants to complete subsequent races: “Commando Half Marathon”, “Commando Marathon”, and “Commando Marathon”.

In the 2022 edition, the start was scheduled for 12.00 and the distance was 10.55 km. The rules of participation in the extreme race included primarily the rules of time measurement, which was carried out using active chips, and determining the order of competitors at the finish line, which was carried out thanks to designated judges. Registration for the race was made via a special form available on the website:

www.biegislupsk.pl (accessed on 7 January 2022), where an entry fee had to be paid to cover the costs associated with organizing the race. Out of 313 registered competitors, 273 people showed up at the start.

In addition to the formal requirements, each competitor could participate in the competition after meeting specific conditions, which included having full field uniforms at the start and during the race, and a 10 kg backpack along the entire route. During the run, drinks were available only at the finish line. It was assumed that each competitor must be self-sufficient.

The regulations of the “Commando Quarter Marathon”, in addition to formal requirements, recommendations, and restrictions, also included important information regarding distinctions, which included honoring the winners in the general classification of women and men, and in the team classification, where the sum of the three best times of competitors from the team with the same name was counted. After crossing the finish line, everyone received a cast medal.

The route ran along forest paths and paved roads. The route was mountainous and difficult in places. On this basis, it was decided that to complete such a route, the competitors would need 2 h, with medical care provided at two points: start–finish and around the 5th kilometer of the route. The route of the eighth edition of the commando run was marked out to be a greater challenge than in the two previous editions, i.e., in 2020 and 2021. This was additionally influenced by the weather, which was not favorable, and the competitors starting in full uniform, military boots, and backpacks weighing 10 kg. The slippery nature of the route along its entire length and many hills, including sharp descents and ascents, meant that the competitors had to use more strength than if they had performed a similar run on flat terrain

Out of 273 runners, 127 took part in the survey. In the analyzed group of 127 runners—as in the entire race—men predominated (over 90%). The surveyed players had a diverse age structure. The youngest participant was 17 and the oldest was 55. The average age was 32, so young people predominated, which is due to the demanding nature of the race. It should be emphasized that the runners came from all over Poland. The average distance between a participant’s place of residence and the race venue was 431 km—a long distance considering the distances between cities in Poland. Some of the competitors came from Słupsk (near the event place), Grabno (17 km), and Miastko (65 km). However, it should be added that the competitors also came from Rzeszów (795), Bochnia (762) and Kraków (716), covering over 700 km. Therefore, the race is important enough for the respondents that they are willing to travel several hundred kilometers to take part in it.

6. Results

Table 1 contains the obtained test results. In general, the participants rated individual elements of the event atmosphere highly, both in the “importance” and “performance” categories. The results ranged from 3.80 to 4.77 on a five-point Likert scale.

In the “importance” category, participants rated event organization the highest (4.23). It is worth adding that the most important thing for the players was event management and hosting (4.53). Due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, it was expected that participants would place the highest priority on safety. It is worth emphasizing that rules and safety received a high value of 4.31 points. In this group of factors, class of the run turned out to be the least important (3.84), which means that the competitors were encouraged to participate by other factors.

The second most important group of factors turned out to be elements relating to the event place (4.13). Attractiveness of the route is an important element of a running event, and the participants confirmed this, awarding it 4.21 points. The attractiveness of the place is confirmed by a willingness to return to the place, which was rated by participants as 4.17 points on the importance scale. The attractiveness of the immediate area turned out to be slightly less important (4.02). This may be due to the fact that runners taking part in competitions do not have time to enjoy the charm of the area.

Relationships between participants are quite important, although this the least important factor in the whole ranking (4.04). The opportunity to share passions (4.17) and integration (4.16) turned out to be more important than the opportunity to compete (3.80). This means that the opportunity to participate in this type of event is more important than winning. This is in line with the spirit of fair play competition.

It is worth adding that in terms of “performance”, in all the categories tested, the results turned out to be higher than in terms of “importance”. This is due to the fact that the participants confirmed that they had completed the difficult race. Satisfaction with completing the route had a positive impact on the perception of the event. Before the race, the competitors felt uncertain, not knowing the route and the difficulties awaiting them. After finishing the run—regardless of the time achieved—most of them felt satisfaction, treating the completion of the run as a success.

The biggest differences between “importance” and “performance” occurred in terms of the event place, which turned out to be more attractive than the runners’ expectations. Slightly smaller differences were noted in the event organization. From the answers provided, it can be concluded that the event met the high expectations of participants in terms of rules and safety and event management and hosting. These are very important factors related to the functioning of rural sport events. The event class was slightly less important. Participants emphasized that they took part in the event to test themselves, not for the importance of the event. Interactions with others were also rated higher—especially the opportunity to share passion and the possibility of integration. This proves that there was a good atmosphere at the event, which brings together running enthusiasts. The competition itself turned out to be less important, as the participants treated it as an additional opportunity resulting from practicing sports.

Figure 1 presents the research results in terms of the IPA model. The results were plotted on two axes, “importance” and “performance”. The data in the figure shows that all rural event atmosphere categories are included in quadrant II (high importance/high efficiency), called: “keep up the good work”. This is a very favorable result, proving the success of the event under study. This is also confirmed by the words of one of the players:

“A wonderful experience. I recommend to everyone. The atmosphere during the race is friendly. Medal-worthy service. Fantastic organization of the event. I would like to thank”.

No category requires changes, but rather all must be maintained at the current level. Of course, maintaining a high level of event organization is not an easy matter in itself, but it is worth emphasizing that there is already a path that must be followed. The research shows that the success of a rural sport event depends on many different factors. It is necessary to organize the event well, ensure the safety of participants, select an appropriately attractive place, and provide opportunities to compete with others. The running route cannot be too monotonous or too easy. Completing it should give participants satisfaction from completing a difficult but interesting challenge. The race route was extremely difficult. An example of the above was undoubtedly the opinion of the majority of players. The six-time winner of the Commando Quarter Marathon said that:

“The route was, as always, difficult, but knowing it helped me because it was in Słupsk that I was building my shape for various competitions. The weather conditions turned out to be an additional difficulty, so it was better to be careful and just reach the finish line safe.”

A debutant won the women’s competition, but she admitted that:

“The route was perfect for me, even though it wasn’t easy, and it was the first time I ran with weights. It’s a lot of effort, but the joy of victory is so great that it rewards all the effort”.

Overall, it is worth emphasizing that the Commando Quarter Marathon was a success. Most competitors (96%) declared their willingness to take part in this cyclical event again, hoping for a difficult challenge.

7. Discussion

The research results confirm the first research hypothesis, according to which atmosphere is a key element involved in building a sport event. The examined factors—event organization, other participants, and place—received high values on the importance scale (above 4). It is worth adding that almost 2/3 of the participants took part in the race not for the first time. Therefore, the results also fit the results presented by Kelley and Turley [

19] that the main factors comprising the quality of event management are the sport competition itself, its place, and other people participating in the event.

With regard to research on the components of event organization, it should be emphasized that rules and safety turned out to be an important factor in building the positive atmosphere of a sport event. This is important both from a sport point of view, as a large group of people competes under strictly defined rules, as well as from a social point of view, as a sense of security is one of the most basic human needs. The participants positively perceived the rules of the competition, the route markings, and safety rules. This is consistent with the results presented by Ryan and Lockyer [

22], according to which this is what players expect—not only good fun, but also clearly defined rules of the game that prevent disorganization.

The results showed that the event participants’ satisfaction with its good organization had an impact on the perception of the event and its surroundings. This is undoubtedly a success factor. Howat and Assaker [

28] and Crespo-Hervás et al. [

29] obtained similar results. The third hypothesis confirmed that satisfaction with a running event has a positive impact on the perception of the event and its atmospheric components.

The organization of the analyzed race is associated with benefits for the host community. Due to its cyclical nature, the event is part of the annual calendar of the commune in which it is held. This place is beginning to become recognizable among runners, slowly awakening their interest in tourism outside the running season. This place has become a popular place for running training, and due to its environmental significance, it has been placed under protection. These effects are in line with the benefits of place indicated by Solberg and Presuss [

31] and Wilson [

33].

It is worth adding that for the surveyed participants, the class of the event turned out to be less important than other elements of the atmosphere. They took part in the competition primarily to test their abilities. It is worth emphasizing that the participants are not professional players and work professionally in their everyday lives. This is consistent with Cowden’s views [

35] that competitions and the results achieved therein are an important element in the careers of professional players. For amateurs, it is more important to participate and test their abilities and skills.

In relation to other participants of the event, the sense of integration with other competitors turned out to be stronger than they expected. Running together, overcoming difficulties, and having a common goal gave the group a sense of integration. This finding is consistent with the results presented by Wiium and Säfvenbom [

37] and Yukhymenko-Lescroart [

45]. People take part in sport competitions not only for the results, but also for their own satisfaction or the opportunity to connect with other people.

Generally, the players showed a willingness to share their passion with others, which confirms the role of passion in building positive relationships [

45]. It is worth adding, however, that willingness to share passion turned out to be much higher after finishing the race. It follows that it was influenced by the satisfaction from participating in difficult competitions. Findings fit into the results of Howat and Assaker [

28] and Crespo-Hervás et al. [

29], according to which satisfaction is the source of positive behavior, in both the near- and long-term.

It is worth emphasizing that, for the participants, the opportunity to compete with others turned out to be less important than other components of the atmosphere. This may be due to the fact that most participants compete mainly with themselves and their own weaknesses. This is a specific way of competing which is appropriate for individual sports. However, it undoubtedly creates the quality of the event, according to Kelley and Turley [

19]. The very willingness to participate in the race under study confirms the views of Gammon and Robinson [

49], because the participants came to the race from all over Poland, so they can be called sport tourists.

However, in general, relationships between participants, although important, turned out to be slightly less important for the respondents than event organization and place. This means that the second research hypothesis was confirmed. These findings are also consistent with the results obtained by Müller et al. [

40], according to which preferences for participating in a sport event usually first reflect a participant’s own interests.

In terms of the event place, reference was made to the attractiveness of the area, the running craze, and the willingness to return. According to the results obtained, the analyzed rural sport event influenced the image of the place and the perception of its attractiveness. This is consistent with the observations of Pop et al. [

56]. It is worth adding that, in the opinion of respondents, as a result of their satisfaction with participating in the event, the attractiveness turned out to be greater than before the event.

For the group of surveyed runners, the attractiveness of the running route turned out to be an important factor in building atmosphere. This finding confirms Qviström’s views on runners’ interactions with the environment, which influence the feeling of attractiveness of the running place [

60]. This, in turn, may contribute to the desire to return to a given place. For the participants of the analyzed race, the difficulty of the route also turned out to be important, which translated into the satisfaction felt after finishing the race. This element fits into the spatial dimensions of the place, determining the suitability of the place for organizing a run or event [

58].

The research results indicate a relationship between level of satisfaction and willingness to return to a place. After finishing the race, the participants rated their willingness to return as much higher. These findings are consistent with those of Allameh et al. [

70], Kaplanidou and Gibson [

27], and Tsuji et al. [

71]. Therefore, the factors creating the atmosphere of an event can significantly contribute to the popularization among sport tourists of not only the event, but also of the place in which the event occurs.

The presented research has some limitations. The study was conducted on a group of participants of one event, which makes it difficult to formulate generalizations. Moreover, the atmosphere of a rural sport event is a complex phenomenon, and its empirical study requires simplifications. Therefore, research was limited to precisely defined elements of the atmosphere. The research limited the scope of the intangible and immeasurable components of the atmosphere of a sport event—it was limited to examining selected attitudes of participants towards other participants—from the perspective of an individual participant. Therefore, future research directions should focus on the intangible and unmeasurable components of a sport event atmosphere, such as fair play, tolerance, and sportsmanship. This is an approach from the perspective of a group, not from the perspective of an individual participant. Research should refer to the common values and beliefs that unite participants in a group. It is also worth considering conducting cross-group studies [

17,

19,

82], which can provide new insights and help identify similarities and differences. Directions for further research may include extending the empirical part to include other sport events. Qualitative research is also noteworthy as it allows for expanding the list of factors shaping the atmosphere.

8. Conclusions

The results of the conducted research indicate the complexity of factors shaping the atmosphere of a rural sport event. The article attempts to assess the atmosphere resulting from the organization and course of a rural sport event. It is worth emphasizing that this is a shot from the point of view of the event participants taking an active part in the run. Referring to the literature, event atmosphere was divided into three basic levels: event organization, relationships between participants, and event place. Specific factors were analyzed within each plane.

The conducted research shows that atmosphere is a key element in building a rural sport event. All analyzed factors turned out to be important and highly rated by respondents at both the “importance” and “performance” stages of the study. It is worth adding that, according to the results obtained, satisfaction with a running event has a positive impact on the perception of the event and its atmospheric components, which influenced positive results in terms of “performance”. Despite slight differences in the assessment, the organization of the event and its place are more important to participants than the presence of other participants, which results from putting their own needs first.

In terms of practical implications, organizing a rural sport event requires special commitment and attention to detail. Organizers should pay attention not only to hard elements, such as rules, place, route, but also to soft factors relating to participants’ feelings, such as a sense of integration or sharing passion. This is a difficult task, but necessary in the process of building atmosphere, which then translates into the attendance and loyalty of participants, and therefore determines the success of the event. A successful rural sport event can also contribute to the willingness of participants to return to the event place on dates other than the event and contribute to the development of sustainable tourism. Policy makers should support the organizers of cyclical events. This is a way to attract not only participants, but also to develop the area in a broader context. In this approach, policy makers should consider the good atmosphere of a sport event as a pull factor and an important element in building the image of not only the event, but also the area. It is also worth involving the local community in the process of building a good atmosphere for the event. This will help create the right background for the event.