Identifying Patterns among Tourism-Oriented Online Communities on Facebook

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Online Communities: Their Specificities and Classification

2.2. Studies Focused on Online Communities in the Tourism Sector

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Tourism-Oriented Online Communities

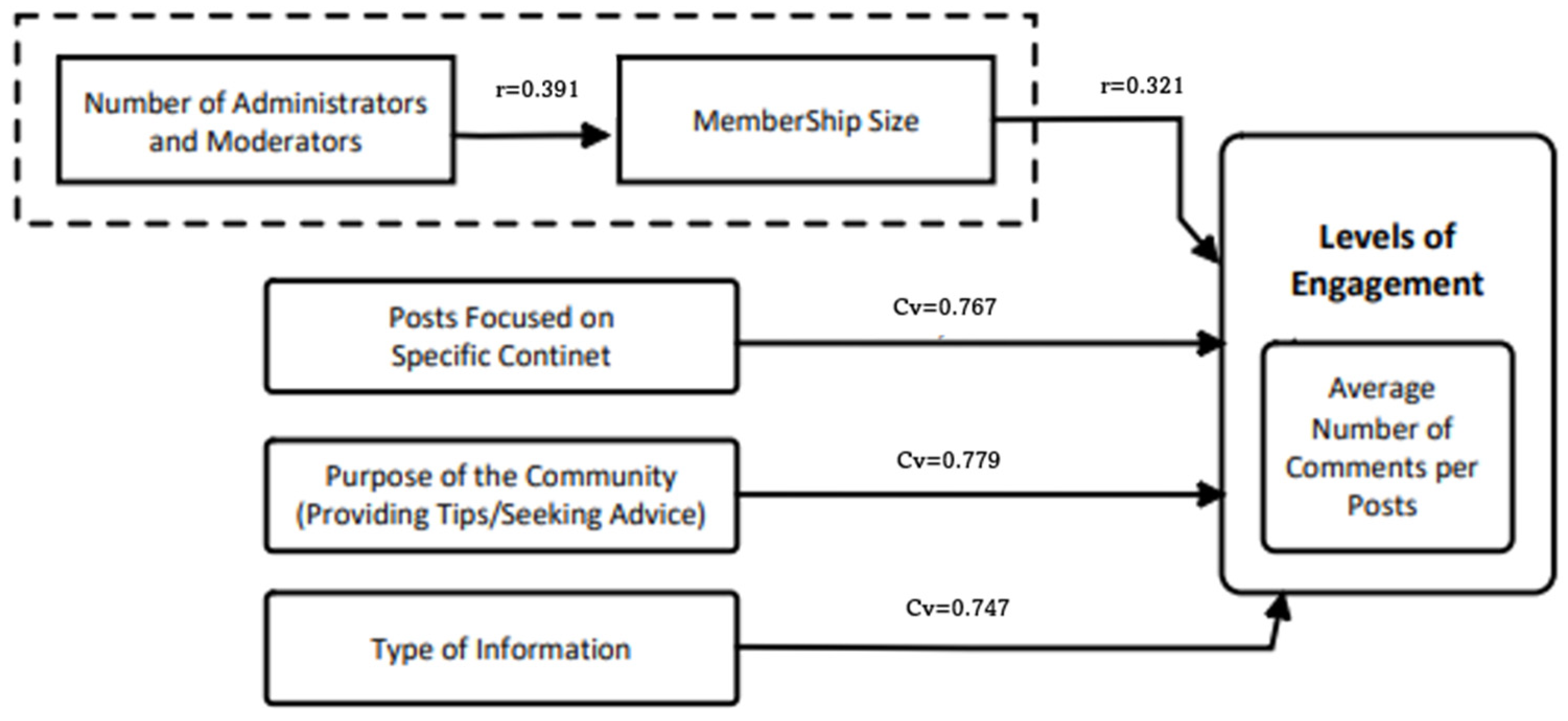

4.2. Factors Influencing Engagement among Members of Online Communities

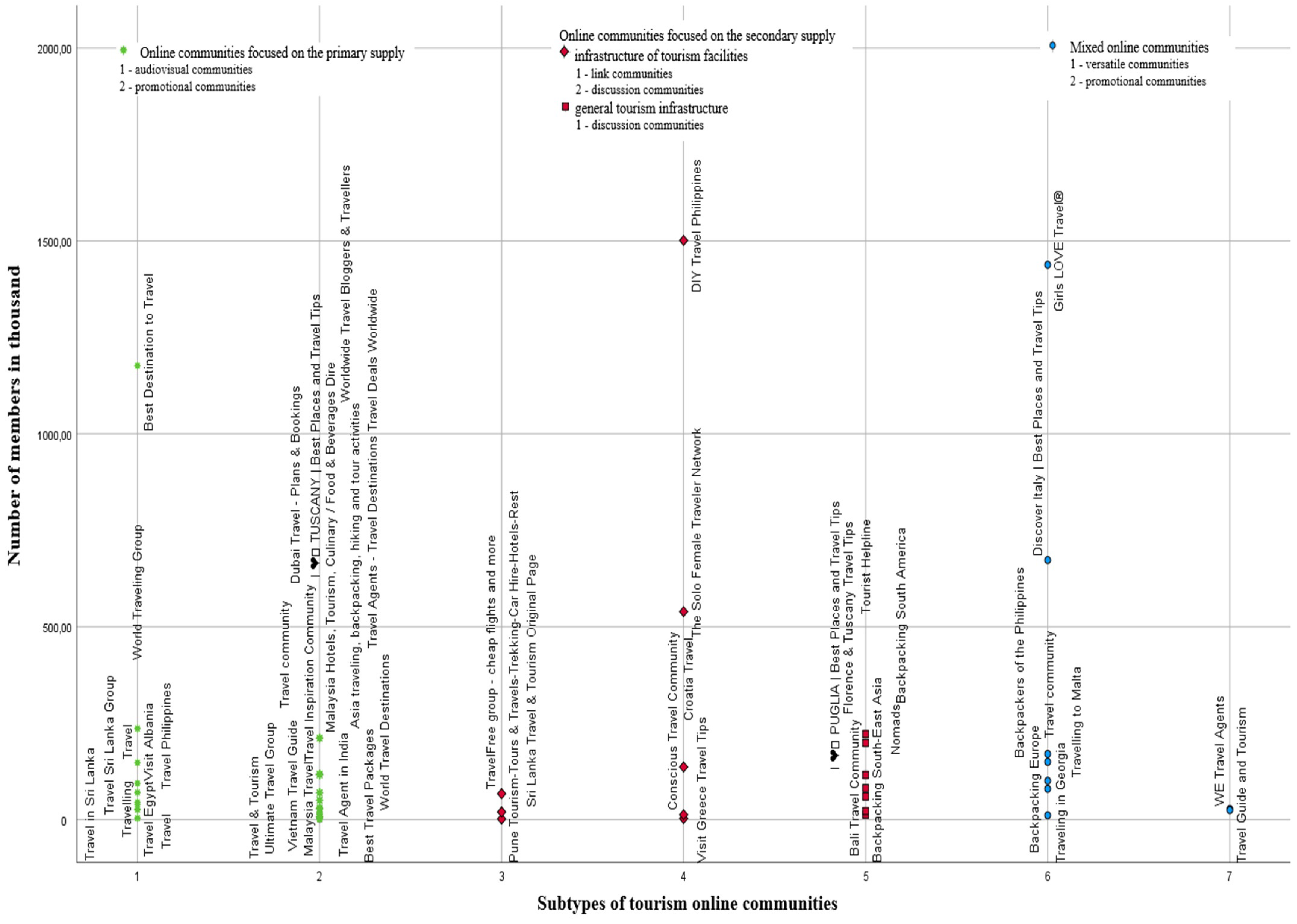

4.3. Typology of Online Communities in Tourism

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, T.-L.; Lai, W.-C.; Yu, T.-K. Participating in online museum communities: An empirical study of Taiwan’s undergraduate students. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 565075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, S.; Flynn, S.; Kylänen, M. Digital transformation in tourism: Modes for continuing professional development in a virtual community of practice. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2021, 2, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, S.; Freundlich, H.; Klotz, M.; Kylänen, M.; Niedoszytko, G.; Swacha, J.; Vollerthum, A. Towards an Online Learning Community on Digitalization in Tourism; Universitätsverlag Potsdam: Postupim, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Kim, W.G.; Okumus, B.; Cobanoglu, C. Understanding online travel communities: A literature review and future research directions in hospitality and tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Poon, P.; Xie, L. Enhancing users’ well-being in virtual medical tourism communities: A configurational analysis of users’ interaction characteristics and social support. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Kraut, R.; Kittur, A. Effectiveness of shared leadership in online communities. In Proceedings of the ACM 2012 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Seattle, DC, USA, 11–15 February 2012; Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2145204.2145269 (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Wahyuni, A.S. Delivering online community service from community perspective: A critical review. J. Community Serv. Empower. 2023, 4, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannettou, S.; Caulfield, T.; Blackburn, J.; De Cristofaro, E.; Sirivianos, M.; Stringhini, G.; Suarez-Tangil, G. On the origins of memes by means of fringe web communities. In Proceedings of the IMC ’18 ACM, Boston, MA, USA, 31 October–2 November 2018. 15p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarzauskiene, A.; Mačiulienė, M. Assessment of users’ behavior in Lithuanian online communities. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1265341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, M.; Frank, J. Designing of online communities of practice to facilitate collaborative learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 5th International Symposium on Emerging Trends and Technologies in Libraries and Information Services (ETTLIS), Noida, India, 21–23 February 2018; pp. 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rolls, K.; Hansen, M.; Jackson, D.; Elliott, D. How health care professionals use social media to create virtual communities: An integrative review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Hyun, S.S. A model of behavioral intentions to follow online travel advice based on social and emotional loneliness scales in the context of online travel communities: The moderating role of emotional expressivity. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepaniuk, K. The model of tourist virtual community members engagement management. Bus. Theory Pr. 2015, 17, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Agag, G.; El-Masry, A.A. Understanding consumer intention to participate in online travel community and effects on consumer intention to purchase travel online and WOM: An integration of innovation diffusion theory and TAM with trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannettou, S.; Caulfield, T.; De Cristofaro, E.; Kourtellis, N.; Leontiadis, I.; Sirivianos, M.; Stringhini, G.; Blackburn, J. The web centipede: Understanding how web communities influence each other through the lens of mainstream and alternative news sources. In Proceedings of the 2017 Internet Measurement Conference, London, UK, 1–3 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. Reciprocity and commitment in online travel communities. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Huang, X. Adoption of a deep learning-based neural network model in the psychological behavior analysis of resident tourism consumption. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 995828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, S.; Mechant, P. Hacia una definición de la Comunidad Virtual. Signo Y Pensam. 2019, 38, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dennis, M.; Halbert, J. Preface. In Community Engagement in the Online Space; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. xiv–xxiii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, D.; Teixeira, A. As complexidades da cibercultura em Pierre Lévy e seus desdobramentos sobre a educação. In XXI Workshop de Informática na Escola; Sociedade Brasileira de Computação: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 2015; pp. 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muryanto, M.A.; Nuzula, I.F.; Venkatesan, T. Online communities, brand recovery, consumer relationships, and repurchase intention. J. Manag. Stud. Dev. 2023, 2, 50–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, K. Virtual communities in Japan. In Proceedings of the Pacific Telecommunications Council 1994 Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–25 November 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, J.; Preece, J. Classification schema for online communities. In AMCIS 1998 Proceedings (Paper 30); AIS eLibrary: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1998; Available online: http://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis1998/30 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Armstrong, A.; Hagel, J. Real profits from virtual communities. McKinsey Q. 1995, 3, 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, G. Information exchange in virtual communities: A typology. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2000, 5, 82. Available online: https://informationr.net/ir/5-4/paper82.html (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Intentional social action in virtual communities. J. Interact. Mark. 2002, 16, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanoevska-Slabeva, K. Toward a community-oriented design of internet platforms. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2002, 6, 71–95. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, C.E. A typology of virtual communities: A multi-disciplinary foundation for future research. J. Comput. Commun. 2004, 10, JCMC1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virnoche, M.E.; Marx, G.T. Only connect—E. M. Forster in an age of electronic communication: Computer-mediated association and community networks. Sociol. Inq. 1997, 67, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, Z.; Parmentier, G. Drivers and mechanisms for online communities performance: A systematic literature review. Eur. Manag. J. 2023, 41, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, I.; Cha, K.; Suh, Y.-K.; Kim, K.-H. Travelers’ parasocial interactions in online travel communities. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 888–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lee, K.Y.; Yang, S.-B. Exploring the effect of heuristic factors on the popularity of user-curated ‘Best places to visit’ recommendations in an online travel community. Inf. Process. Manag. 2019, 56, 1391–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Manstrly, D.; Ali, F.; Steedman, C. Virtual travel community members’ stickiness behaviour: How and when it develops. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafipour, A.A.; Heidari, M.; Foroozanfar, M.H. Describing the virtual reality and virtual community: Applications and implications for tourism industry. Kuwait Chapter Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2014, 3, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueg, C.H. Mediation, expansion and immediacy: How online communities revolutionize information access in the tourism sector. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth European Conference on Information Systems, ECIS 2006, Göteborg, Sweden, 12 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Law, R.; Murphy, J. Helpful reviewers in TripAdvisor, an online travel community. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2011, 28, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Jin, M.; Ren, P. Empirical research on knowledge sharing factors in travel online community. Pak. J. Stat. 2014, 30, 815–826. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, D.; Lin, Z.; Zhuo, R. What drives consumer knowledge sharing in online travel communities?: Personal attributes or e-service factors? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dippelreiter, B.; Grün, C.; Pöttler, M.; Seidel, I.; Berger, H.; Dittenbach, M.; Pesenhofer, A. Online Tourism Communities on the Path to Web 2.0: An Evaluation. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2008, 10, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Defining the virtual tourist community: Implications for tourism marketing. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illum, S.F.; Ivanov, S.H.; Liang, Y. Using virtual communities in tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2009, 31, 335–340. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1413628 (accessed on 14 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-J.; Chen, Y.-H.; Chung, Y.-S. Trust factors influencing virtual community members: A study of transaction communities. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. Understanding the intention to follow the advice obtained in an online travel community. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, S.; Li, G.; Choi, C. Understanding service quality in a virtual travel community environment. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, M.-T.; Jeng, D.J.-F.; Lin, C. The Importance of Attribution: Connecting Online Travel Communities with Online Travel Agents. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2014, 56, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Bai, X.; Park, A. Understanding sustained participation in virtual travel communities from the perspectives of is success model and flow theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 475–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, E.C.S. Distributed fascinating knowledge over an online travel community. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Hyun, S.S. A model of value-creating practices, trusting beliefs, and online tourist community behaviors: Risk aversion as a moderating variable. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1868–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.; Jang, J.; Barrett, E.B. Linking website interactivity to consumer behavioral intention in an online travel community: The mediating role of utilitarian value and online trust. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 18, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; George, B. Not all posts are treated equal: An empirical investigation of post replying behavior in an online travel community. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Li, J.; Prybutok, V.R. Posting-related attributes driving differential engagement behaviors in online travel communities. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1263–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Rahman, Z. Measuring customer social participation in online travel communities: Scale development and validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2017, 8, 432–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglieri, D.; Consoli, R. Collaborative innovation in tourism: Managing virtual communities. TQM J. 2009, 21, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. Relationship quality, community promotion and brand loyalty in virtual communities: Evidence from free software communities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2010, 30, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, W.; Seshadri, S. From virtual travelers to real friends: Relationship-building insights from an online travel community. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1822–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zhang, H. Building interpersonal trust in a travel-related virtual community: A case study on a Guangzhou couchsurfing community. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimrod, G. The benefits of and constraints to participation in seniors’ online communities. Leis. Stud. 2012, 33, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dencheva, S. Analysis of virtual communities in tourism. EcoForum J. 2013, 2, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. New members’ integration: Key factor of success in online travel communities. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimrod, G. Probing the audience of seniors’ online communities. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2013, 68, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors of Studies Sorted Chronologically | Nature of the Online Community | Examined Online Communities |

|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [40] | undefined social network |

|

| Lueg [35] | online community website |

|

| Dippelreiter et. al. [39] | online community website |

|

| Baglieri & Consoli [53] | travel agency website |

|

| Illum et al. [41] | online community websites for tourism students |

|

| Casaló et al. [43] | online community website |

|

| Lee et al. [36] | online community website |

|

| Casaló et al. [59] | online community website |

|

| Dencheva [58] |

| |

| Nimrod [60] | online community website |

|

| Elliot et al. [44] | Travel agency website |

|

| Bui et al. [45] | online community website |

|

| Ku [47] | online community website |

|

| Najafipour et al. [34] | online community website |

|

| Wang et al. [37] | online community website |

|

| Kunj & Seshadri [55] | online community website |

|

| Lee & Hyun [12] | online community website |

|

| Stepaniuk [13] |

| |

| Agag & El-Masry [14] | online community website |

|

| Lee & Hyun [48] | online community website |

|

| Luo & Zhang [56] | online community website |

|

| Gao et al. [46] | online community website |

|

| Jeon et al. [49] | online community website |

|

| Kamboj & Rahman [52] | online community website |

|

| Fang et al. [50] | online community website |

|

| Fang et al. [51] | online community website |

|

| Belanche et al. [16] | online community website |

|

| Choi et al. [31] | online community website |

|

| Li et al. [32] | online community website |

|

| El-Manstrly et al. [33] | online community website |

|

| Chen et al. [1] | online community website |

|

| Marx et al. [2] | online community website |

|

| Marx et al. [3] | online community website |

|

| Peng et al. [5] | online community website |

|

| Online Community Name | Membership Size (in Thousands) | Age | Number of Administrators and Moderators | Average Number of Comments per Post | Average Daily Growth Rate of Posts in % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIY Travel Philippines | 1501.24 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 4.35 |

| Girls LOVE Travel® | 1438.18 | 8 | 26 | 32 | 2.72 |

| Best Destination to Travel | 1176.64 | 5 | 7 | 52 | 13.20 |

| Discover Italy | Best Places and Travel Tips | 672.21 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 5.05 |

| The Solo Female Traveler Network | 539.46 | 7 | 8 | 46 | 3.15 |

| World Traveling Group | 236.43 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 6.89 |

| Tourist Helpline | 222.28 | 10 | 16 | 12 | 2.97 |

| Travel community | 211.59 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Nomads | 199.18 | 10 | 6 | 89 | 3.36 |

| Travel community | 170.42 | 6 | 16 | 31 | 2.97 |

| Backpackers of the Philippines | 149.71 | 11 | 12 | 4 | 5.56 |

| Travel | 147.3 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 1.69 |

| Croatia Travel | 136.65 | 11 | 4 | 11 | 5.45 |

| Dubai Travel—Plans & Bookings | 117.99 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Travel Inspiration Community | 116.95 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 2.17 |

I  PUGLIA | Best Places and Travel Tips PUGLIA | Best Places and Travel Tips | 116.13 | 2 | 3 | 45 | 5.00 |

| Travelling to Malta | 100.97 | 7 | 7 | 35 | 0.83 |

| Visit Albania | 94.43 | 1 | 4 | 35 | 4.98 |

| Bali Travel Community | 82.00 | 9 | 11 | 6 | 6.68 |

| Backpacking Europe | 80.06 | 17 | 9 | 7 | 5.81 |

| Travel Philippines | 70.39 | 12 | 24 | 0 | 8.21 |

| Worldwide Travel Bloggers & Travellers | 69.89 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 4.11 |

| TravelFree group—cheap flights and more | 67.55 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 1.28 |

| Florence & Tuscany Travel Tips | 60.01 | 4 | 5 | 17 | 3.78 |

I  TUSCANY | Best Places and Travel Tips TUSCANY | Best Places and Travel Tips | 50.54 | 2 | 3 | 20 | 6.61 |

| Travel Egypt | 44.72 | 11 | 12 | 80 | 2.21 |

| Travel in Sri Lanka | 39.53 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 5.48 |

| Travel & Tourism | 31.51 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Travel Agent in India | 28.72 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 3.09 |

| Travel Guide and Tourism | 27.64 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 1.23 |

| Malaysia Travel | 27.62 | 13 | 13 | 8 | 6.10 |

| Travelling | 27.15 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 5.10 |

| Travel | 26.1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2.63 |

| WE Travel Agents | 24.72 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 1.55 |

| Backpacking South America | 22.31 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 0.63 |

| Sri Lanka Travel & Tourism Original Page | 20.03 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2.79 |

| Best Travel Packages | 18.59 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 5.46 |

| World Travel Destinations | 13.91 | 3 | 13 | 0 | 8.47 |

| Conscious Travel Community | 12.85 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 0.00 |

| Backpacking South-East Asia | 12.81 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 5.84 |

| Traveling in Georgia | 11.23 | 9 | 2 | 13 | 4.64 |

| Vietnam Travel Guide | 7.43 | 13 | 3 | 2 | 4.44 |

| Tourist and Hotels | 6.44 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Asia traveling, backpacking, hiking and tour activities | 4.76 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 2.95 |

| Travel Sri Lanka Group | 4.05 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 4.67 |

| Visit Greece Travel Tips | 3.05 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 11.11 |

| Malaysia Hotels, Tourism, Culinary / Food & Beverages Dire | 2.03 | 12 | 5 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Pune Tourism-Tours & Travels-Trekking-Car Hire-Hotels-Rest | 1.79 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3.23 |

| Ultimate Travel Group | 1.36 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 11.76 |

| Travel Agents—Travel Destinations Travel Deals Worldwide | 1.3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 5.62 |

| Selected quantitative characteristics of examined online communities | |||||

| Mean () | 164.99 | 7.34 | 4.12% | 11.71 | 6.56 |

| Standard deviation (sx) | ±334.26 | ±4.04 | ±3.01 | ±20.40 | ±5.41 |

| Coefficient of variation (vk) | 202.59% | 55.04% | 73.06% | 174.21% | 82.47% |

| Median () in thousand | 47.62 | 7.00 | 3.95 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Mode () in thousand | 1.30 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

| Cluster Name | Category of Published Information | Nature of Published Information |

|---|---|---|

| General Tourism Infrastructure Communities | information on general tourism infrastructure (insurance, parking, car rentals, etc.) | discussion posts |

| Tourism Services Communities | information on tourism services (accommodation services, dining services, ancillary services, etc.) | hyperlinks |

| Comprehensive Tourism Services and Destinations Communities | information on tourism services and destinations | discussion posts, hyperlinks, online audiovisual materials |

| Focused Tourism Services Communities | information on tourism services (accommodation services, dining services, ancillary services, etc.) | discussion posts |

| Destination Highlight Communities | information on destinations (natural attractions, cultural–historical attractions, organized events) | online audiovisual materials |

| Destination Promotion Communities | information on destinations (natural attractions, cultural–historical attractions, organized events) | promotional materials |

| Integrated Tourism Services and Destinations Promotion Communities | information on tourism services and destinations | promotional materials |

| Category of Online Communities | Subcategory of Online Communities | Community Management | Community Intent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Online communities centred on primary offerings | Audiovisual communities | community members | providing advice |

| Promotional communities | external businesses | providing advice | |

| Online communities centred on secondary offerings | Link communities | moderators and members | providing advice |

| Discussion communities (tourism infrastructure) | community members | providing advice | |

| Discussion communities (general infrastructure) | community members | seeking advice | |

| Mixed online communities | Versatile communities | community members | seeking and providing advice |

| Promotional communities | external businesses | providing advice |

| Category of Online Communities | Subcategory of Online Communities | Quantitative Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Number of Members (in Thousands) | Average Daily Growth Rate of Posts (in %) | Average Age of the Community | Average Number of Administrators and Moderators | ||

| Online communities centered on primary offerings | Audiovisual communities | 186.67 | 5.51 | 8.4 | 8 |

| Promotional communities | 43.25 | 5.92 | 6.82 | 5 | |

| Online communities centered on secondary offerings | Link communities | 29.79 | 2.03 | 4.33 | 4 |

| Discussion communities (tourism infrastructure) | 438.65 | 6.01 | 8.0 | 6 | |

| Discussion communities (general infrastructure) | 102.10 | 3.73 | 7.0 | 7 | |

| Mixed online communities | Versatile communities | 374.68 | 3.93 | 8.7 | 11 |

| Promotional communities | 26.17 | 6.39 | 6.5 | 6 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zabudská, E.; Pompurová, K. Identifying Patterns among Tourism-Oriented Online Communities on Facebook. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 5, 830-847. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5030048

Zabudská E, Pompurová K. Identifying Patterns among Tourism-Oriented Online Communities on Facebook. Tourism and Hospitality. 2024; 5(3):830-847. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5030048

Chicago/Turabian StyleZabudská, Eva, and Kristína Pompurová. 2024. "Identifying Patterns among Tourism-Oriented Online Communities on Facebook" Tourism and Hospitality 5, no. 3: 830-847. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5030048

APA StyleZabudská, E., & Pompurová, K. (2024). Identifying Patterns among Tourism-Oriented Online Communities on Facebook. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(3), 830-847. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5030048