How COVID-19 Affected Portuguese Travel Intentions—A PLS-SEM Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Fear of Traveling, Anxiety, and Fear of the Consequences of COVID-19

2.2. Risk of Traveling

2.3. Travel Behavior

2.4. Intention to Travel

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Population and Sample

3.2. Data Collection Instruments

3.3. Procedures

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

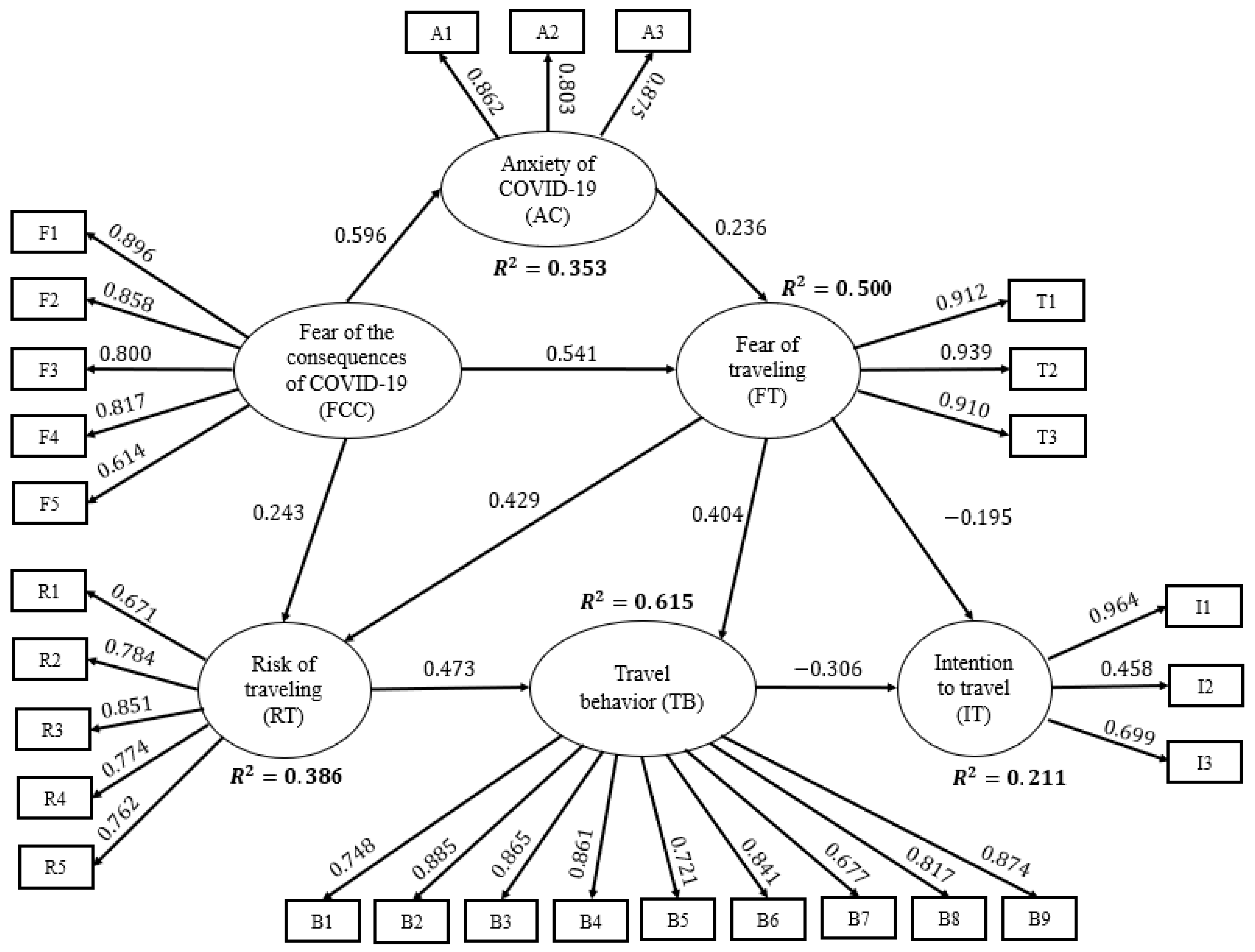

4.2. Evaluation of the Structural Model

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aebli, A.; Volgger, M.; Taplin, R.A. two-dimensional approach to travel motivation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.; Garcia, G.M.; Limberger, P.F.; Zucco, F.D.; Quadros, C.M.B. Percepções dos riscos de viagens aéreas durante a pandemia da COVID-19 no estado de Santa Catarina-Brasil. TURYDES Rev. Sobre Tur. Desarro. Local Sosten. 2020, 13, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; Oliveira, M.; Ratten, V.; Tavares, F.O.; Tavares, V.C. A reflection on explanatory factors for COVID-19: A comparative study between countries. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 63, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Braun, E.; Gyimóthy, S. Too afraid to Travel? Development of a pandemic (COVID-19) anxiety travel scale (PATS). Tour. Manag. 2021, 84, 104286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G.; Morrill, W. The Challenge of COVID-19 for Youth Travel. Rev. An. Bras. Estud. Tur.-ABET 2021, 11, 1–8. Available online: https://periodicos.ufjf.br/index.php/abet/article/view/33299 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Toubes, D.R.; Araújo Vila, N.; Fraiz Brea, J.A. Changes in Consumption Patterns and Tourist Promotion after the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1332–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J. The effect of COVID-19 and subsequent social distancing on travel behavior. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 5, 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, N.A.; Long, F. To travel, or not to travel? The impacts of travel constraints and perceived travel risk on travel intention among Malaysian tourists amid the COVID-19. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, F. COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.; Henry, R.E.; Lee, Y.K.; Berro, A.; Maskery, B.A. The effects of past SARS experience and proximity on declines in numbers of travelers to the Republic of Korea during the 2015 MERS outbreak: A retrospective study. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 30, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, H.I.; Chen, C.C.; Tseng, W.C.; Ju, L.F.; Huang, B.W. Assessing impacts of SARS and Avian Flu on international tourism demand to Asia. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novelli, M.; Burgess, L.G.; Jones, A.; Ritchie, B.W. ‘No Ebola… still doomed’—The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Lam, C.F. Travel anxiety, risk attitude and travel intentions towards “Travel Bubble” destinations in Hong Kong: Effect of the fear of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokni, L. The Psychological Consequences of COVID-19 Pandemic in Tourism Sector: A Systematic Review. Iran. J. Public Health 2021, 50, 1743–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Chang, P.J. The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.L.; Al-Ansi, A.; Lee, M.J.; Han, H. Impact of health risk perception on avoidance of international travel in the wake of a pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiza, T.; Kruger, M. Ceding to their fears: A taxonomic analysis of heterogeneity in COVID-19 associated perceived risk and intended travel behaviour. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Bao, J.; Tang, C. Profiling and evaluating Chinese consumers regarding post-COVID-19 travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonmoy, P.; Rohit, C.; Nafis, A. Impact of COVID-19 on daily travel behaviour: A literature review. Transp. Saf. Environ. 2022, 4, tdac013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.Y.T.; Jahari, S.A. Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post disaster Japan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Pizam, A.; Bahja, F. Antecedents and outcomes of health risk perceptions in tourism, following the COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, B.D.D.; Moyle, C.L.L.; Bec, A.A.; Scott, N. The next frontier in tourism emotion research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1393–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoog, N.N.; Stroebe, W.W.; Wit, J.B. The processing of fear-arousing communications: How biased processing leads to persuasion. Soc. Influ. 2008, 3, 84–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, L.; Moen, B.E.; Rundmo, T. Explaining risk perception. An evaluation of the psychometric paradigm in risk perception research. Rotunde Publ. Rotunde 2004, 84, 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington-Gray, L.; Schroeder, A.; Kaplanidou, K.K. Examining the influence of past travel experience, general web searching behaviour and risk perception on future travel intentions. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Tour. 2011, 1, 64–92. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger, Y.Y.; Mavondo, F. Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: Implications of travel risk perception. J. Travel. Res. 2005, 43, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F. Tourism, terrorism, and political instability. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 416–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maser, B.; Weiermair, K. Travel decision-making: From the vintage point of perceived risk and information preferences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1998, 7, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, L. International tourism and its global health consequences. J. Travel Res. 2003, 41, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Gibson, H. Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittichainuwat, B.N.; Chakraborty, G. Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Influence of terrorism risk on foreign tourism decisions. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 112–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyanto, I.; Wiblishauser, M.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Schroeder, A. The dynamics of travel avoidance: The case of Ebola in the US. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, M.F.; Pennington-Gray, L. Profiling risk perceptions of tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Song, H.J.; Bendle, L.J.; Kim, M.J.; Han, H. The impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions for 2009 H1N1 influenza on travel intentions: A model of goal-directed behavior. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.K.; Agarwal, S.; Kim, H.J. Influences of travel constraints on the people with disabilities’ intention to travel: An application of Seligman’s helplessness theory. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.T.; Fazekas, K.I. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: A theory-informed, systematic review. Prev. Med. 2007, 45, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, N. It’s the End of the World Economy as We Know It. The New York Times, 20 April 2020. Available online: www.nytimes.com/2020/04/16/upshot/world-economy-restructuring-coronavirus.html (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Papadimitriou, D.; Kaplanidou, K. Marketing Destinations and Venues for Conferences, Conventions and Business Events, 2nd ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.; King, B.; Bauer, T. Understanding Chinese tourists’ travel behavior: A qualitative study. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 731–743. [Google Scholar]

- Wachyuni, S.S.S.; Kusumaningrum, D.A. The Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic: How are the Future Tourist Behavior? J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2020, 33, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, C.C.; Joun, Y.Y.; Han, H.H.; Chung, N. A structural model for destination travel intention as a media exposure: Belief-desire-intention model perspetive. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1338–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.A.; Martin, J.D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 6576–6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R. Tourist’s perceptions of safety and security while visiting Cape Town. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 5755–5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canhota, C. Qual a importância do estudo piloto. In Investigação Passo a Passo: Perguntas e Respostas para Investigação Clínica; Silva, E.E., Ed.; APMCG: Lisbon, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, C.B.; Canhota, C.; Silva, E.E.; Simões, J.; Yaphe, J.; Maia, M.C.; Ribas, M.J.; Melo, M.; Nicola, P.J.; Braga, R.; et al. Investigação Passo a Passo: Perguntas e Respostas para a Investigação Clínica; APMCG: Lisbon, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023.

- SMARTPLS GmbH, SMART PLS 4 [Software]. 2023. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; SAGE Publication Ltd.: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Marôco, J. Análise Estatística Com o SPSS Statistics 25, 7th ed.; Report Number: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international Marketing. Adv. Int. Mark. 2009, 20, 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 381 | 50.1 |

| Male | 379 | 49.9 | |

| Marital status | Single | 269 | 35.4 |

| Married or in a civil partnership | 413 | 54.3 | |

| Widowed | 6 | 0.8 | |

| Divorced or separated | 72 | 9.5 | |

| Academic background | Basic education (up to 9th grade) | 11 | 1.5 |

| Secondary education (up to 12th grade) | 104 | 13.7 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 349 | 45.9 | |

| Master’s/PhD | 296 | 38.9 | |

| Professional situation | Employee | 530 | 69.7 |

| Self-employed worker | 123 | 16.2 | |

| Unemployed | 35 | 4.6 | |

| Student | 51 | 6.7 | |

| Retired | 19 | 2.5 | |

| Domestic worker | 2 | 0.3 | |

| Level of income | Very low | 29 | 3.8 |

| Low | 65 | 8.6 | |

| Medium | 544 | 71.6 | |

| High | 118 | 15.5 | |

| Very high | 4 | 0.5 |

| Items | M (SD) | Loadings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fear of the consequences of COVID-19 ( = 0.859, CR = 0.899, AVE = 0.645) | |||

| F1. I am afraid of being infected with COVID-19. | 3.30 (1.25) | 0.896 | |

| F2. Thinking about the possibility of being infected with COVID-19 makes me uncomfortable. | 3.44 (1.28) | 0.858 | |

| F3. I am afraid of dying because of COVID-19. | 2.86 (1.44) | 0.800 | |

| F4. I am afraid of the health consequences that could result from the pandemic situation. | 3.18 (1.24) | 0.817 | |

| F5. I am afraid of the social consequences that could result from the pandemic situation. | 3.48 (1.19) | 0.614 | |

| Anxiety of COVID-19 ( = 0.810, CR = 0.884, AVE = 0.718) | |||

| A1. I get nervous or anxious when I see or read news in newspapers and on social media about COVID-19. | 2.46 (1.18) | 0.862 | |

| A2. I can’t sleep because I’m worried about being infected with COVID-19. | 1.38 (0.76) | 0.803 | |

| A3. My heart races or flutters at the thought of being infected with COVID-19. | 1.65 (0.98) | 0.875 | |

| Fear of traveling ( = 0.910, CR = 0.943, AVE = 0.847) | |||

| T1. Due to the pandemic situation, I am afraid to risk my life when traveling. | 2.77 (1.23) | 0.912 | |

| T2. Watching the news about the pandemic situation makes me afraid to travel. | 2.67 (1.26) | 0.939 | |

| T3. The identification of the Delta variant of COVID-19 has left me with less desire to travel. | 2.53 (1.29) | 0.910 | |

| Risk of traveling ( = 0.821, CR = 0.874, AVE = 0.583) | |||

| R1. Tourism is the main driver of the spread of COVID-19. | 2.38 (1.10) | 0.671 | |

| R2. Staying in a hotel is a risk because there are many people from different countries, who may be carriers of the virus. | 2.53 (1.14) | 0.784 | |

| R3. I fear that the virus could be carried by tourists into my immediate environment. | 2.73 (1.12) | 0.851 | |

| R4. Travel should be banned to prevent a wider spread of the virus. | 2.10 (1.13) | 0.774 | |

| R5. Currently, traveling to destinations with a high number of COVID-19 cases should be avoided. | 3.78 (1.17) | 0.726 | |

| Travel behavior ( = 0.935, CR = 0.946, AVE = 0.661) | |||

| B1. I would currently cancel my travel plans to countries with a high number of COVID-19 cases. | 3.59 (1.30) | 0.748 | |

| B2. I would currently avoid air travel. | 2.88 (1.39) | 0.885 | |

| B3. I would currently avoid traveling by boat. | 2.91 (1.41) | 0.865 | |

| B4. I would currently avoid traveling by train. | 2.74 (1.33) | 0.861 | |

| B5. I would currently avoid big events. | 3.66 (1.25) | 0.721 | |

| B6. I would currently avoid visiting tourist attractions. | 3.06 (1.30) | 0.841 | |

| B7. I would currently avoid domestic travel (traveling within the country). | 1.94 (1.08) | 0.677 | |

| B8. I would currently avoid any contact with other tourists. | 2.88 (1.24) | 0.817 | |

| B9. I would currently avoid traveling abroad. | 2.95 (1.41) | 0.874 | |

| Intention to travel ( = 0.728, CR = 0.766, AVE = 0.542) | |||

| I1. I travel, whenever I have a chance to travel, even in a pandemic situation. | 2.69 (1.26) | 0.964 | |

| I2. I will do my best to improve my way of traveling by meeting the required standards. | 4.18 (1.01) | 0.458 | |

| I3. I will continue to collect travel-related information for the future, even in a pandemic situation. | 3.67 (1.15) | 0.699 | |

| FCC | AC | FT | RT | TB | IT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCC | 0.803 | |||||

| AC | 0.595 | 0.847 | ||||

| FT | 0.681 | 0.558 | 0.920 | |||

| RT | 0.535 | 0.380 | 0.595 | 0.764 | ||

| TB | 0.563 | 0.394 | 0.686 | 0.714 | 0.831 | |

| IT | −0.223 | −0.179 | −0.403 | −0.234 | −0.438 | 0.736 |

| Mean | 3.25 | 1.83 | 2.65 | 2.70 | 2.96 | 3.51 |

| Standard deviation | 1.02 | 0.83 | 1.16 | 0.86 | 1.06 | 0.92 |

| Path | Coefficient | t-Value ª | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: FCC FT | 0.541 | 15.782 *** | Supported |

| H2: FCC AC | 0.596 | 24.990 *** | Supported |

| H3: AC FT | 0.236 | 6.166 *** | Supported |

| H4: FCC RT | 0.243 | 5.486 *** | Supported |

| H5: FT RT | 0.429 | 10.027 *** | Supported |

| H6: RT TB | 0.473 | 15.859 *** | Supported |

| H7: FT TB | 0.404 | 12.845 *** | Supported |

| H8: FT IT | −0.195 | 4.348 *** | Supported |

| H9: TB IT | −0.306 | 6.502 *** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, E.; Oliveira, M.F.; Tavares, F.O. How COVID-19 Affected Portuguese Travel Intentions—A PLS-SEM Model. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 5, 657-671. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5030039

Santos E, Oliveira MF, Tavares FO. How COVID-19 Affected Portuguese Travel Intentions—A PLS-SEM Model. Tourism and Hospitality. 2024; 5(3):657-671. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5030039

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Eulália, Margarida Freitas Oliveira, and Fernando Oliveira Tavares. 2024. "How COVID-19 Affected Portuguese Travel Intentions—A PLS-SEM Model" Tourism and Hospitality 5, no. 3: 657-671. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5030039

APA StyleSantos, E., Oliveira, M. F., & Tavares, F. O. (2024). How COVID-19 Affected Portuguese Travel Intentions—A PLS-SEM Model. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(3), 657-671. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5030039