Assessing Economic Impacts of Mile High 420 Festival in Colorado

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Economic Impact of Events and Festivals

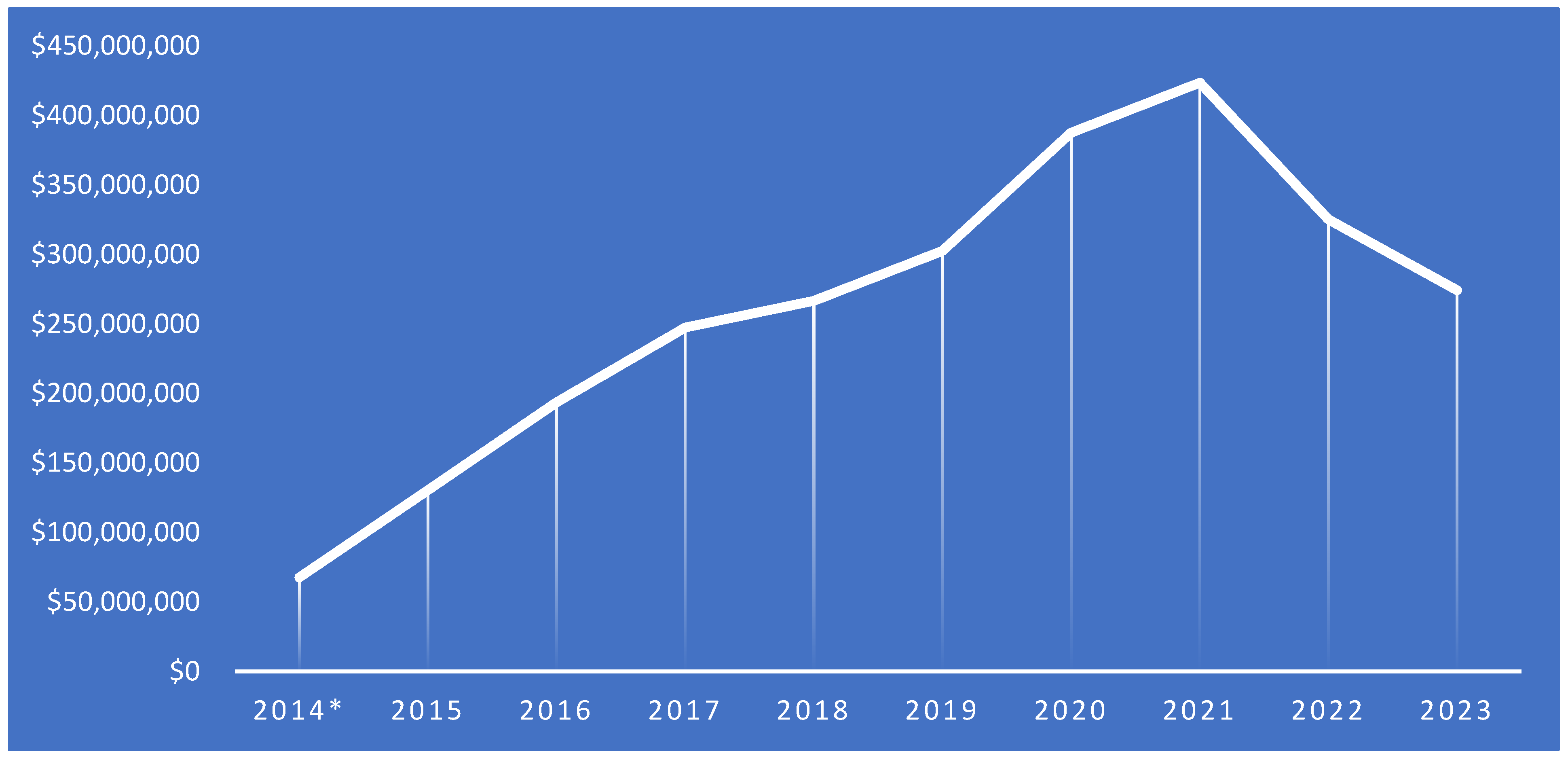

2.2. Cannabis-Themed Events and Festivals

2.3. Input–Output Model

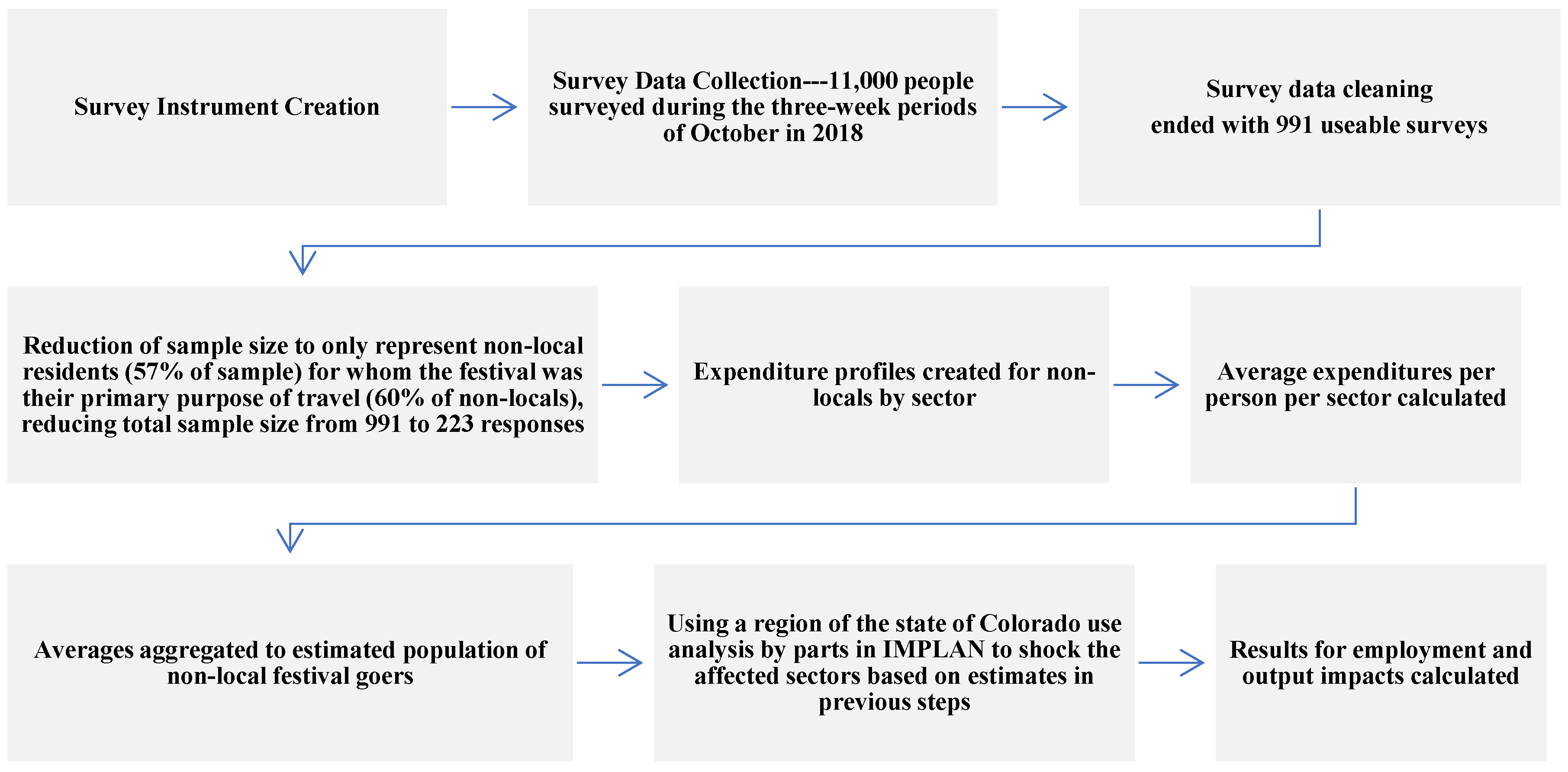

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Setting: 2018 Mile High 420 Festival

3.2. Research Instrument and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Characteristics

4.2. Expenditure Profile

4.3. Economic Impacts: Direct, Indirect, and Induced

4.4. Tax Impacts of 420 Festival Spending by Out-of-State Primary Purpose Visitors

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

Study Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crompton, J.L.; Lee, S.H.; Shuster, T.J. A guide for undertaking economic impact studies: The Springfest example. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Forsyth, P.; Spurr, R. Estimating the impacts of special events on an economy. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Banyai, M.; Smith, S. Expenditures, motivations, and food involvement among food festival visitors: The Hefei, China, Crawfish Festival. J. China Tour. Res. 2013, 9, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Conference of State Legislatures. State Medical Cannabis Laws. 2024. Available online: https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Kang, S.K. Place attachment, image, and support for marijuana tourism in Colorado. Sage Open 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.K.; Miller, J.; Lee, J.S. The cannabis festival: Quality, satisfaction, and intention to return. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2019, 10, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Lee, J. Support of marijuana tourism in Colorado: A residents’ perspective using social exchange theory. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorado Department of Revenue. Colorado Department of Revenue, Marijuana Tax Data. 2024. Available online: https://cdor.colorado.gov/data-and-reports/marijuana-data/marijuana-tax-reports (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Light, M.; Orens, A.; Rowberry, J.; Saloga, C. The Economic Impact of Marijuana Legalization in Colorado; Marijuana Policy Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, C.; Hill, M.; Phillips, R. Taxing Cannabis. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. 2019. Available online: https://itep.org/wp-content/uploads/012319-TaxingCannabis_ITEP_DavisHillPhillips.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Janeczko, B.; Mules, T.; Ritchie, B. Estimating the Economic Impacts of Festivals and Events: A Research Guide; Research Report Series; Sustainable Tourism Pty Ltd.: Gold Coast MC, Australia, 2002; Available online: https://sustain.pata.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Mules_EcoImpactsFestivals_v6.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Rogers, J. Guidelines: Survey Procedures for Tourism Economic Impact Assessments of Gated Events and Festivals; Canadian Tourism Commission: Vancouver, BC, Canada; Research Resolutions & Consulting, Ltd.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Skliamis, K.; Korf, D. An Exploratory Study of Cannabis Festivals and Their Attendees in Two European Cities: Amsterdam and Berlin. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2017, 50, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skliamis, K.; Benschop, A.; Korf, D.J. Cannabis users and stigma: A comparison of users from European countries with different cannabis policies. Eur. J. Criminol. 2022, 19, 1483–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounteney, J.; Griffiths, P.; Sedefov, R.; Noor, A.; Vicente, J.; Simon, R. The drug situation in Europe: An overview of data available on illicit drugs and new psychoactive substances from European monitoring in 2015. Addiction 2016, 111, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines-Saah, R.J.; Johnson, J.L.; Repta, R.; Ostry, A.; Young, M.L.; Shoveller, J.; Ratner, P.A. The privileged normalization of marijuana use—An analysis of Canadian newspaper reporting, 1997–2007. Crit. Public Health 2014, 24, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.C.; Mahmood, R.; Abdullah, H. Economic growth, tourism, and selected macroeconomic variables: A triangular causal relationship in Malaysia. J. Appl. Econ. Res. 2013, 7, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keul, A.; Eisenhauer, B. Making the high country: Cannabis tourism in Colorado USA. Ann. Leis. Res. 2019, 22, 140–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, R. The Role of Tourism in Sustainable Development. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. 2021. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/environmentalscience/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.001.0001/acrefore-9780199389414-e-387 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Getz, D. Event tourism: Evaluating the impacts. In Travel, Tourism and Hospitality Research: A Handbook for Managers and Researchers; Ritchie, J.R.B., Goeldner, C.R., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Raybould, M.; Fredline, L. An investigation of measurement error in visitor expenditure surveys. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2012, 3, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.; Thilmany, D. Exploring localized economic dynamics: Methods driven case studies of transformation and growth in agricultural and food markets. Econ. Dev. Q. 2017, 31, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D.; Sills, E.; Cubbage, F. The significance of festivals to rural economics: Estimating the economic impacts of Scottish highland games in North Carolina. J. Travel Res. 2003, 41, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Burkard, M.; Brown, L.; Clare, J. Economic Impacts of the Southern Rocky Mountain Agricultural Conference. Regional Economic Development Institute White Paper. 2023. Available online: https://csuredi.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/COMBINED-SRMAC-study-with-cover-page.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Tyrrell, T.J.; Johnston, R.J. A Framework for Assessing Direct Economic Impacts of Tourist Events: Distinguishing Origins, Destinations, and Causes of Expenditures. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frechtling, D.C.; Horvath, E. Estimating the multiplier effects of tourism expenditures on a local economy through a regional input-output model. J. Travel Res. 1999, 37, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuck, S. Exploring the Overall Distributional and Resiliency Implications of Investments in Rural Outdoor Tourism: The Case of Fishers Peak State Park. Master’s Thesis, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Burkard, M.; Hill, R. The Economic Contribution of River-Based Recreation in the Little Yampa Canyon, Colorado. Regional Economic Development Institute Report. 2023. Available online: https://csuredi.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/REDI-Report-Yampa-Nov23.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Upneja, A.; Shafer, E.L.; Seo, W.; Yoon, J. Economic Benefits of Sport Fishing and Angler Wildlife Watching in Pennsylvania. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.W. Measuring the economic value of tourism at the regional scale: The case of the County of Grey. E-Rev. Tour. Res. 2005, 3, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.T.; Fletcher, R.R.; Clabaugh, T. A comparison of characteristics, regional expenditures, and economics: The impact of visitors to historical sites compared to other recreational visitors. J. Travel Res. 1993, 32, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, K. Putting out the welcome mat. Reg. Rev. 2003, 13, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, E.A.; Sampol, C.J. Tourist expenditure for mass tourism markets. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 624–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.X.; Tian, T.T.; Cook, S. Impact of Travel on State Economics; Travel Industry Association of America: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; Leal Londoño, M.D.P. Festival cities and tourism: Challenges and prospects. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2022, 14, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilton, J.J.; Nickerson, N.P. Collecting and using visitor spending data. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frechtling, D.C. An assessment of visitor expenditure methods and models. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, S.E.; Labuschagne, V. Festival visitors’ expenditure: A comparison of visitor expenditure at the Vryfees Arts Festival. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2016, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J.L. Economic impact studies: Instruments for political shenanigans? J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.J.; Choi, H.C.; Dupej, S.; Zolfaghari, A. Motivations, risks, and constraints: An analysis of affective and cognitive images for cannabis tourism in Canada. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2023, 4, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupej, S.; Nepal, S. Cannabis tourism as an agent of normalization: A Canadian perspective. Tour. Rev. Int. 2021, 25, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.W.M. Cannabis and tourism: A future UK industry perspective. J. Tour. Futures 2019, 5, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.K.; Lee, J. A cannabis festival in urban space: Visitors’ motivation and travel activity. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2021, 4, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, B. The value of multipliers and their policy implications. Tour. Manag. 1982, 3, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mules, T. Kate Fischer or Liz Hurley? Which model should I use? In Proceedings of the 1996 Australian Tourism and Hospitality Conference, Bureau of Tourism Research, Canberra, Australia, 6–9 February 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.; Kang, S.; Milholland, E.; Furness, A. Planning a cannabis festival: A study of the 4/20 Festival in Denver, Colorado. J. Hosp. Tour. Cases 2022, 9, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilmany, D.; Costanigro, M. The 2012 Economic Contribution of Colorado’s Wine Industry: The Roles of Consumers, Wineries, and Tourism. 2013. Available online: https://mountainscholar.org/bitstream/handle/10217/192910/FACFAGRE_UCSU522W722013.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Furness, A. Phone Interview; Team Player Production: Denver, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stynes, D. Approaches to Estimating the Economic Impacts of Tourism: Some Examples. Michigan State University. 1999. Available online: https://www.msu.edu/course/prr/840/econimpact/pdf/ecimpvol2.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Colorado Department of Revenue. Colorado Department of Revenue, Marijuana Tax Data. 2022. Available online: https://cdor.colorado.gov/data-and-reports/marijuana-data/marijuana-tax-reports (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Harnik, P.; Crompton, J.L. Measuring the total economic value of a park system to a community. Manag. Leis. 2014, 19, 188–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.W.; Scott, D.; Thigpen, J.F.; Kim, S.S. The economic impact of a birding festival. Festiv. Manag. Event Tour. 1998, 5, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L.; Lee, S.H. The economic impact of 30 sports tournaments, festivals, and spectator events in seven U.S. cities. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2000, 18, 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Sundance Film Festival Reached a Record Economic impact of $92.1 Million According to Reports (Sundance Institute, n.d.). 2006. Available online: https://www.sundance.org/blogs/news/sundance_film_festival_reaches_record_economic_impact_of_921_million/ (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Schecter, J.G. The Dollars in Doubloons. Biz New Orleans. Available online: https://www.bizneworleans.com/the-dollars-in-doubloons/ (accessed on 1 February 2016).

- Destination Analysis. Big Sur Food & Wine Festival Economic Impact & Attendee Survey Report of Findings. 2016. Available online: https://assets.simpleviewinc.com/simpleview/image/upload/v1/clients/montereycounty/big-sur-food-and-wine-festival-economic-impact-report--final-revised_aea3ef6e-a076-4113-8d2c-1825669a00d2.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Charleston Wine and Food. Charleston Wine and Food ’22 Delivers $26 Million in Economic Impact. CRBJ BizWire.com. 2022. Available online: https://charlestonbusiness.com/ (accessed on 29 April 2023).

- Wen, J.; Meng, F.; Ying, T.; Belhassen, Y. A study of segmentation of cannabis-oriented tourists from China based on motivation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Mathews, S.; Anatol, M. Building a Model of Tourism for the People: The Case for Caribbean Cannabis Tourism. J. East. Caribb. Stud. 2021, 46, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, M.L. Greened Out: Improving Virginia's Recreational Marijuana Legislation. Lib. Univ. Law Rev. 2023, 17. Available online: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lu_law_review/vol17/iss2/3 (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Rogers, J.M.; Iudicello, J.E.; Marcondes, M.C.G.; Morgan, E.E.; Cherner, M.; Ellis, R.J.; Letemdre, S.L.; Heaton, R.K.; Grant, I. The Combined Effects of Cannabis, Methamphetamine, and HIV on Neurocognition. Viruses 2023, 15, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Rees, D.I. The Public Health Effects of Legalizing Marijuana. J. Econ Lit. 2023, 61, 86–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C. Assessing the impact of a major sporting event: The role of environmental accounting. Tour. Econ. 2008, 14, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Kang, J.H. Effects of sports event satisfaction on team identification and revisit intent. Sport Mark. Q. 2015, 24, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Event Management and Event Tourism; Cognizant Communication: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, H.; Bull, A.; Walo, M. A comparison of survey methods to estimate visitor expenditure at a local event. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. The impact of memory on expenditures recall in tourism conversion studies. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.; Wilson, J.; Thilmany, D.; Winter, S. Determining economic contributions and impacts: What is the difference and why do we care? J. Reg. Anal. Policy 2007, 37, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.A.; Hong, G.; Morrison, A.M. Household expenditure patterns for tourism products and services. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1995, 4, 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S.; Bai, B.; Hong, G.; O’Leary, J. Understanding travel expenditure patterns: A study of Japanese pleasure travelers to the United States by income level. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Gnoth, J. Tourist consumption systems among overseas visitors: Reporting on American, German, and Australian visitors to New Zealand. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leones, J.; Colby, B.; Crandall, K. Tracking expenditures of the elusive nature tourists of Southeastern Arizona. J. Travel Res. 1998, 36, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbey, G.; Graefe, A. Repeat tourism, play and monetary spending. Ann. Tour. Res. 1991, 18, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitler, D. Five Things to Know about Free Mile High 520 Festival. Fox 31 News. Available online: https://kdvr.com/news/local/5-things-to-know-about-free-mile-high-420-festival/ (accessed on 29 April 2022).

| Industry | Direct Impact | Indirect Impact | Induced Impact | Total Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marijuana Retail (stores) | 1.000 | 1.029 | 0.369 | 2.398 |

| Marijuana Manufacturing and Banking | 1.000 | 0.984 | 0.355 | 2.340 |

| Marijuana Cultivation | 1.000 | 0.793 | 0.332 | 2.126 |

| Variables (N = 233) | Characteristics | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 41.6 |

| Female | 58.4 | |

| Age | 21–30 | 36.1 |

| 31–40 | 39.5 | |

| 41–50 | 20.2 | |

| 51–60 | 3.9 | |

| 61–70 | 0.4 | |

| Marital status | Single | 33.0 |

| Married | 29.6 | |

| Divorced | 7.3 | |

| Separated | 0.9 | |

| In a domestic partnership or civil union | 7.7 | |

| Single but cohabiting with a significant other | 20.6 | |

| Education | High school diploma | 30.0 |

| Junior college degree | 34.3 | |

| University degree | 20.2 | |

| Graduate school degree | 9.0 | |

| Ethnicity | Black/African American | 41.2 |

| White/Caucasian | 28.3 | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 15.0 | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3.4 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islanders | 1.7 | |

| Multiple Ethnicity | 10.3 | |

| Income | <USD 20 K | 8.6 |

| USD 20 K–34.99 K | 22.7 | |

| USD 35 K–49.99 K | 23.6 | |

| USD 50 K–74.99 K | 21.9 | |

| USD 75 K–99.99 K | 13.3 | |

| USD 100 K or more | 9.9 | |

| Residing state | Texas | 11.9% |

| Florida | 5.3 | |

| Illinois | 5.1 | |

| New York | 4.1 | |

| New Mexico/Missouri * | 3.1 | |

| Georgia/Tennessee * | 2.9 | |

| Oklahoma/Kansas/Michigan/Minnesota/Pennsylvania * | 2.3 | |

| Wisconsin | 2.1 | |

| California | 1.8 | |

| # of previous festival attendances | None (first-time attendee) | 45.9 |

| Once | 35.6 | |

| Twice | 9.4 | |

| Three times | 7.7 | |

| Four times | 1.3 | |

| Lodging | Marijuana-friendly accommodation | 28.3 |

| Non-marijuana-friendly accommodation | 50.6 | |

| Friends or family | 4.7 | |

| Airbnb | 13.7 | |

| Other | 2.6 | |

| Travel size | Mean: 3.82 people Mode: 2 people | |

| LOS | Mean: 3.73 nights Mode: 3 nights | |

| Information source | Internet | 67.4 |

| Past experience | 18.9 | |

| Festival organizer | 7.3 | |

| Social media | 33.5 | |

| Advertisement | 4.7 | |

| Word of mouth | 32.6 | |

| Expense Category | Per-Person Expenditure | Total Sector Expenditure (Per-Person USD × 25,650 *) |

|---|---|---|

| Marijuana-related activities and shopping | USD 523.89 | USD 13,437,700.43 |

| Lodging | USD 404.58 | USD 10,377,385.15 |

| Dining, drinking, and nightlife | USD 328.69 | USD 8,430,931.96 |

| Non-marijuana-related activities and shopping | USD 301.09 | USD 7,722,991.96 |

| Transportation excluding airfare | USD 260.78 | USD 6,689,073.91 |

| Sightseeing | USD 87.50 | USD 2,244,486.52 |

| Other accommodation expense | USD 66.99 | USD 1,718,325.98 |

| Recreational activities | USD 25.69 | USD 658,870.43 |

| Gambling | USD 14.48 | USD 371,367.39 |

| TOTAL | USD 2013.69 | USD 51,651,133.74 |

| Employment | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | 527 | USD 46,665,714 |

| Indirect Effect | 125 | USD 29,056,593 |

| Induced Effect | 135 | USD 19,662,774 |

| Total Effect | 787 | USD 95,385,082 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, S.; Hill, R.; Thilmany, D. Assessing Economic Impacts of Mile High 420 Festival in Colorado. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 5, 521-536. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5030032

Kang S, Hill R, Thilmany D. Assessing Economic Impacts of Mile High 420 Festival in Colorado. Tourism and Hospitality. 2024; 5(3):521-536. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5030032

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Soo, Rebecca Hill, and Dawn Thilmany. 2024. "Assessing Economic Impacts of Mile High 420 Festival in Colorado" Tourism and Hospitality 5, no. 3: 521-536. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5030032

APA StyleKang, S., Hill, R., & Thilmany, D. (2024). Assessing Economic Impacts of Mile High 420 Festival in Colorado. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(3), 521-536. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5030032