‘I Just Want to Go Home’: Emotional Wellbeing Impacts of COVID-19 Restrictions on VFR Travel

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. VFR Travel

1.2. Identity, Home and Place Attachment

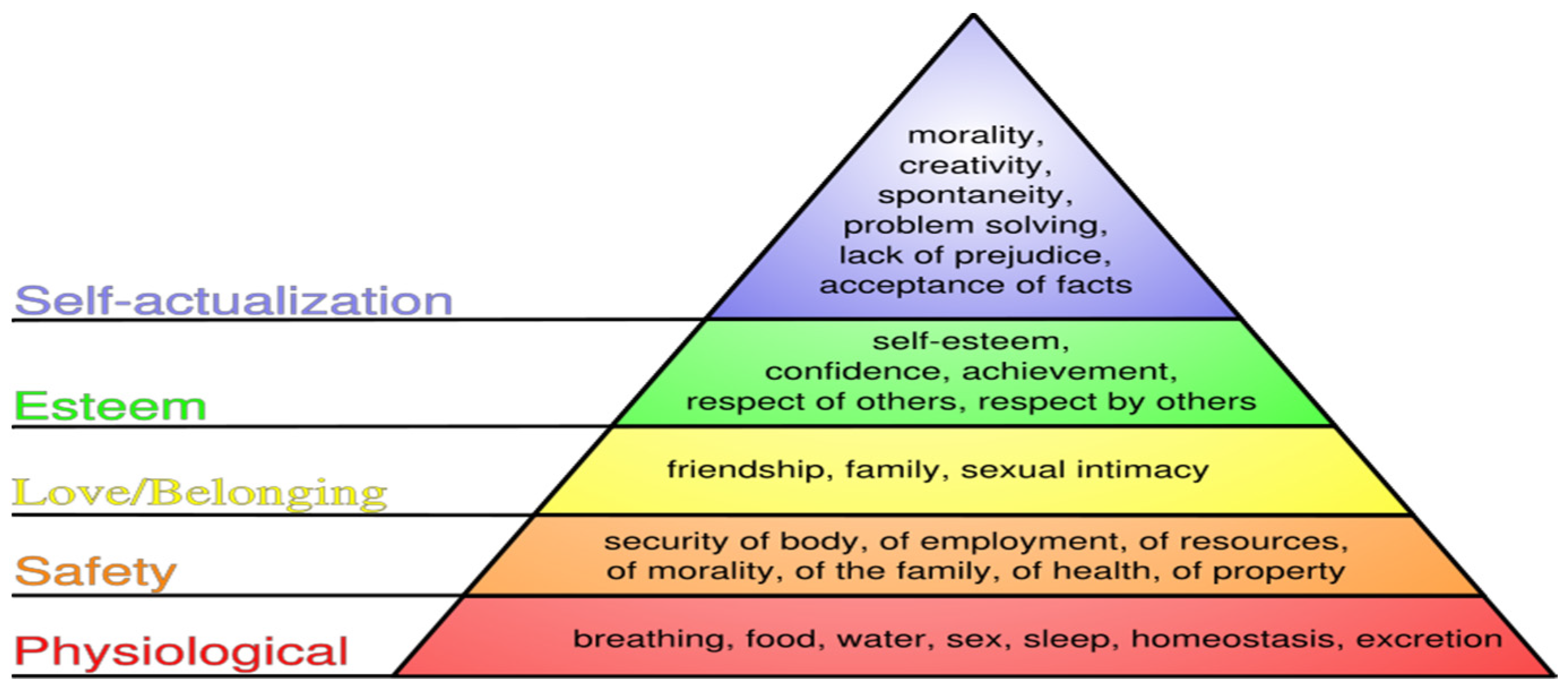

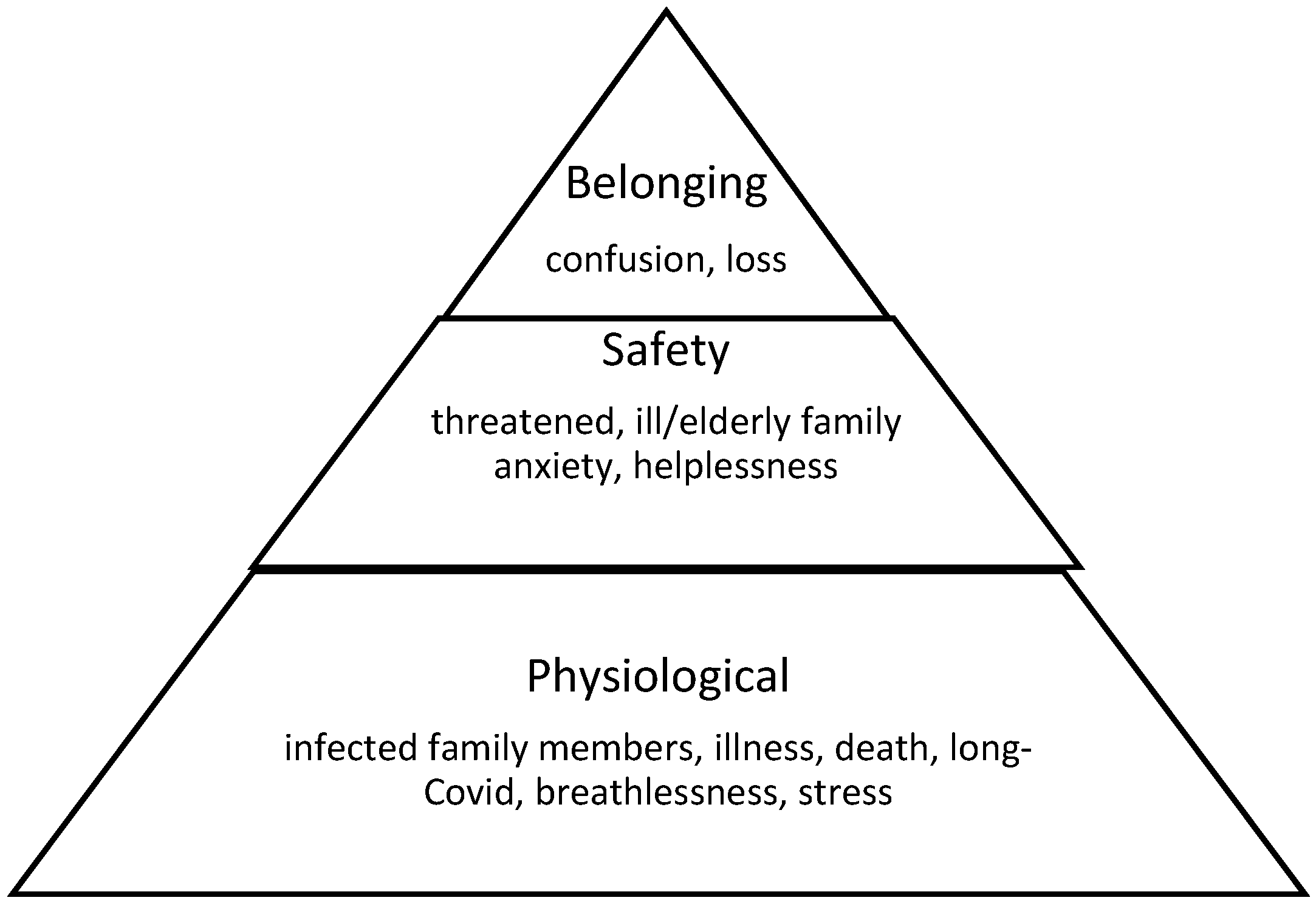

1.3. Human Needs and Differential Tourist Gazes

2. Methods

Sampling and Data Collection

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Safety, Love and Belonging

3.2. Emotional Impacts

3.2.1. Wellbeing Impacts

3.2.2. Coping Strategies

3.3. Performing Connectivity

3.4. The Post-Covid Tourist Gaze

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO. International Tourism Highlights 2020. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/ (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Backer, E.; Morrison, A.M. VFR Travel: Is It Still Underestimated? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škare, M.; Soriano, D.R.; Porada-Rochoń, M. Impact of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, J.; Mubeen, R.; Iorember, P.T.; Raza, S.; Mamirkulova, G. Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on tourism: Transformational potential and implications for a sustainable recovery of the travel and leisure industry. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 2021, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary, J.T.; Morrison, A.M. The VFR—Visiting Friends and Relatives–Market: Desperately Seeking Respect. J. Tour. Stud. 1995, 6, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G.; Pearce, P.; Morrison, A.M.; Green, D.; O’Leary, J.T. Developing a Typology for Understanding Visiting Friends and Relatives Markets. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.H. Preparation, simulation and the creation of community: Exodus and the case of diaspora education tourism. In Tourism, Diasporas and Space; Coles, T., Timothy, D.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, T.; Timothy, D.J. “My field is the world”: Conceptualizing diasporas, travel and tourism. In Tourism, Diasporas and Space; Coles, T., Timothy, D.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M.; Bryce, D.; Murdy, S. Delivering the Past. J. Travel Res. 2016, 56, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fowler, S. Ancestral Tourism. Insights 2003, D31–D36. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, J.; Urry, J.; Axhausen, K.W. Networks and Tourism: Mobile Social Life. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-J.; King, B.; Suntikul, W. VFR Tourism and the Tourist Gaze: Overseas Migrant Perceptions of Home. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentveld, E.; Labas, A.; Edwards, S.; Morrison, A.M. Now is the time: VFR travel desperately seeking respect. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, E. VFR travel: It is underestimated. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hughes, H.; Allen, D. Holidays of the Irish Diaspora: The Pull of the “Homeland”? Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Hall, C.M. Guest Editorial: Tourism and migration. Tour. Geogr. 2000, 2, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Hall, C.M. Tourism and migration: New relationships between production and consumption. Tour. Geogr. 2000, 2, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.; Ashworth, G.; Tunbridge, J. A Geography of Heritage: Power, Culture and Economy; Arnold: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. Space, Place and Placelessness in the Culturally Regenerated City. In Cultural Tourism: Global and Local Perspectives; Haworth Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, C. An Ethnography of Englishness: Experiencing Identity through Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin & Spread of Nationalism, Revised ed.; Verso: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, G. Social Geographies: Space and Society; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, P. My Own Island Home: The Orkney Homecoming. J. Mater. Cult. 2004, 9, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, K.; Healey, M. Place attachment and place identity: First-year undergraduates making the transition from home to university. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, N.R.; White, P.B. Home and Away: Tourists in a Connected World. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castles, S.; Miller, M.J. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World, 4th ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, M.V.; Feldman, R. Place attachment in a developmental and cultural context. J. Environ. Psychol. 1993, 13, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.T.; Mowen, A.J.; Tarrant, M. Linking Place Preferences with Place Meaning: An Examination of the Relationship between Place Motivation and Place Attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneafsey, M. Tourism and Place Identity: A case-study in rural Ireland. Ir. Geogr. 1998, 31, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L. Travel motivation, benefits and constraints to destinations. In Destination Marketing and Management: Theories and Applications; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.H.; Huang, S. Travel Motivations: A Critical Review of the Concept’s Development. In Tourism Management: Analysis, Behaviour and Strategy; Woodside, A., Martin, D., Eds.; Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J.; Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze 3.0; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf, M.; Backer, E. A content analysis of Visiting Friends and Relatives (VFR) travel research. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2015, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinshead, K. The Shift to Constructivism in Social Inquiry: Some Pointers for Tourism Studies. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2006, 31, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinckerhoff-Jackson, J. A Sense of Place, A Sense of Time; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. Collective feelings: Or, the Impressions Left by Others. Theory Cult. Soc. 2004, 21, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buda, D.; d’ Hautessere, A.M.; Johnstone, L. Feelings and Tourism Studies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, N. Emotional entanglements in tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 53, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buda, D.M. Affective Tourism; Dark Routes in Conflict; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- d’Hauteserre, A.-M. Affect theory and the attractivity of destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 55, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C. Beyond ‘a trip to the seaside’: Exploring emotions and family tourism experiences. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 24, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrador-Pons, P. Being-on-Holiday: Tourist Dwelling, Bodies and Space. Tour. Stud. 2003, 3, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.; Bondi, L.; Smith, M. Emotional Geographies; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, C. Analysing Wellness Tourism Provision: A Retreat Operators’ Study. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2010, 17, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrador, P. The place of the family in tourism research: Domesticity and thick sociality by the pool. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoz, D. The Mutual Gaze. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living; Bantam Dell Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Simkova, E.; Holzner, J. Motivation of Tourism Participants. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 159, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Backer, E.; Ritchie, B. VFR Travel: A Viable Market for Tourism Crisis and Disaster Recovery? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interview and Survey Questions |

|---|

| Where is “home” for you? (your parents)? * Even though you live in England, what is your level of identification/identity in relation to your homeland/your parents’ homeland? (options ranged from “Strongly identify” (if someone asked my identity, I would name that country first), to “Low level identify” How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect you and your family? ** What worries did you have about your/your family’s health? ** Can you talk about your emotional responses to the pandemic (during lockdowns/restricted travel) ** During “normal times” how often do you visit your homeland/your parents’ homeland? * During COVID Lockdown, can you describe how it felt NOT to be able to travel to see friends and relatives? How did COVID restrictions around travel to see friends and relatives affect your wellbeing? Do you think living in a different country made COVID experiences worse? If so, how? ** Can you talk about how being able to see your family abroad regularly matters to your own sense of identity, love and belonging? ** What strategies did you use to cope with not being able to travel to see family? Have you been on a Visiting Friends and Relatives trip since restrictions have ended? Can you describe what the experience of being able to travel to see family again felt like? Do you think you looked at your family or your homeland in a new or different way this time, compared to other visits in the past? Can you discuss that a little? ** Based on your answers so far, can you comment on the importance of VFR to you, personally? |

| Emotion/Theme | Most Commonly Expressed Phrases/Words |

|---|---|

| Negative | Awful, dreadful, suffocating, sad, devastated, angry |

| Loss of Control | Helpless, frustrated, stuck, trapped, locked-in “knowing that I could not go and that I was blocked in the UK was a bit overwhelming”. |

| Separate | Isolated, lonely, apart |

| Anxiety | Insecure, worried, stressed, afraid |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kelly, C. ‘I Just Want to Go Home’: Emotional Wellbeing Impacts of COVID-19 Restrictions on VFR Travel. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 634-650. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030039

Kelly C. ‘I Just Want to Go Home’: Emotional Wellbeing Impacts of COVID-19 Restrictions on VFR Travel. Tourism and Hospitality. 2022; 3(3):634-650. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030039

Chicago/Turabian StyleKelly, Catherine. 2022. "‘I Just Want to Go Home’: Emotional Wellbeing Impacts of COVID-19 Restrictions on VFR Travel" Tourism and Hospitality 3, no. 3: 634-650. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030039

APA StyleKelly, C. (2022). ‘I Just Want to Go Home’: Emotional Wellbeing Impacts of COVID-19 Restrictions on VFR Travel. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(3), 634-650. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3030039