Differential Impacts of COVID-19 on College Student Tourism Jobs: Insights from Vacationland-Maine, USA

Abstract

:1. Introduction/Background

1.1. Maine Tourism

1.2. University of Southern Maine and COVID-19

1.3. Purpose of the Study

- How have USM students’ jobs in tourism and recreation industries compared to other sectors been impacted by COVID-19? and

- What can the university and industry learn from this to support and attract back the workforce they lost?

2. Literature Review

2.1. COVID-19 and Worldwide Tourism Jobs

2.2. COVID-19 and USA Tourism Jobs

2.3. COVID-19 and Maine Tourism Jobs

2.4. Employment during College Is Vital for Many Students

2.5. COVID-19 Impacts on Student Employment

2.6. COVID-19 Impacts on College Students’ Tourism Employment at USM, Maine

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Participant Demographics

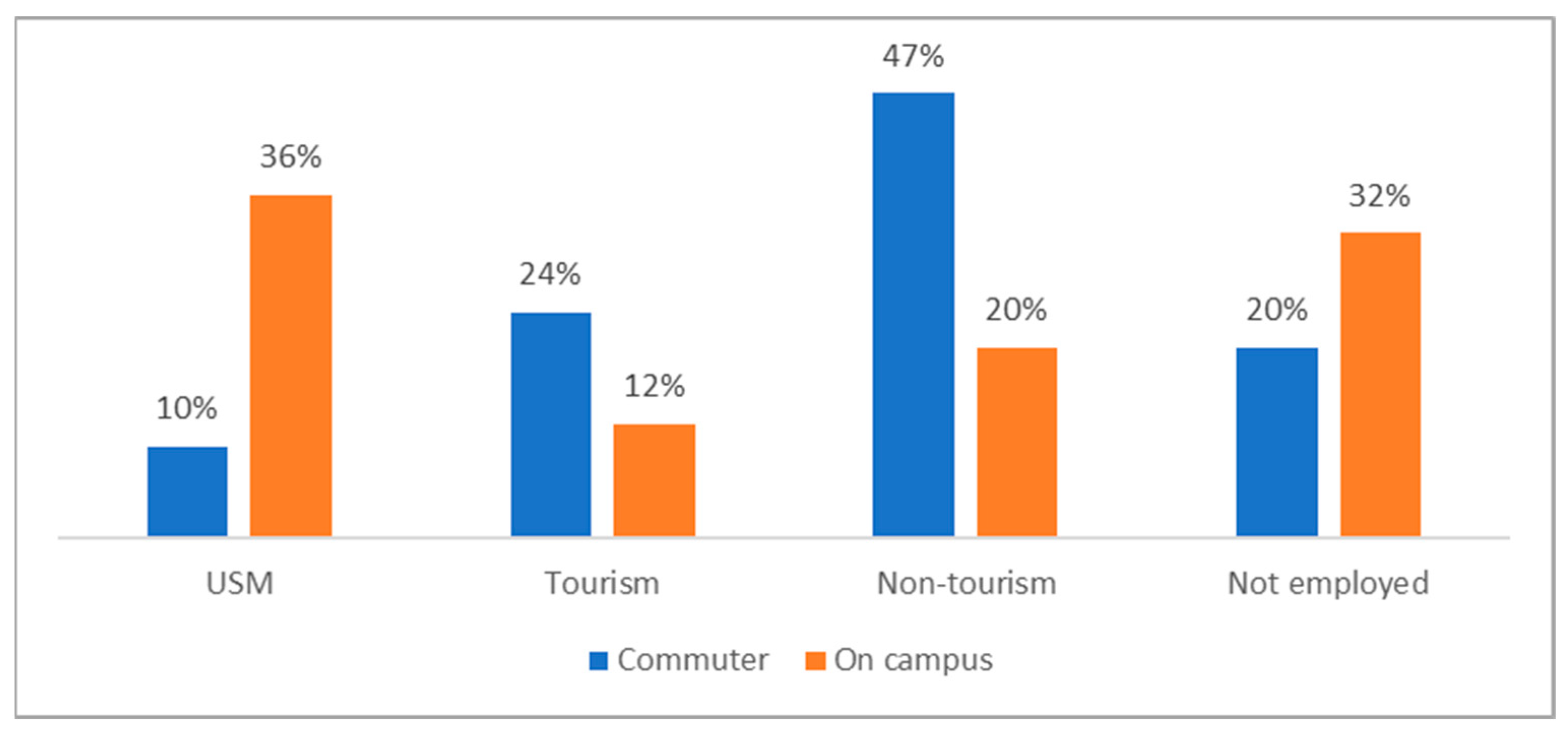

4.2. Employment Industry of USM Undergraduate Students

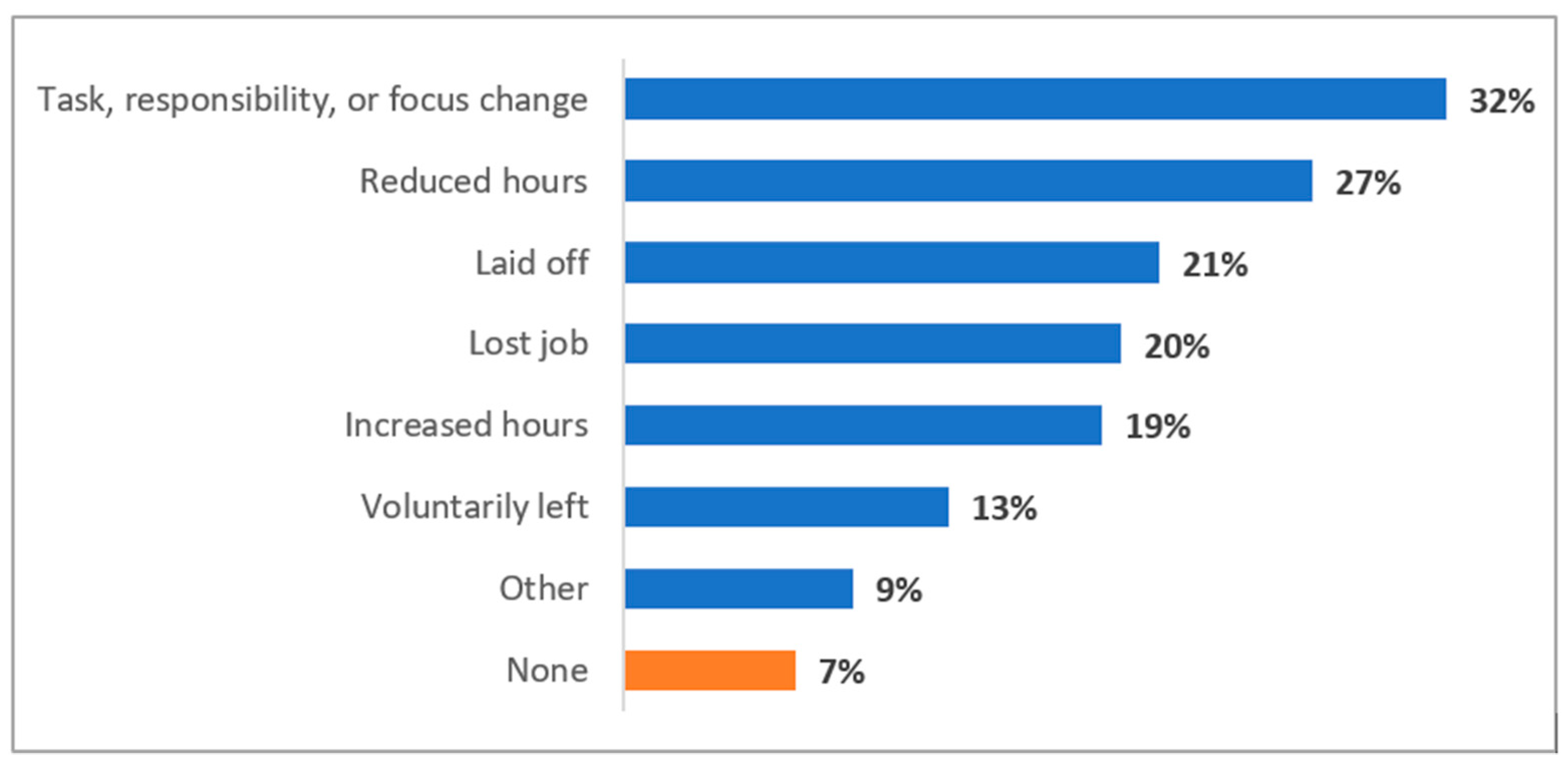

4.3. Initial Impact of COVID-19 on Employment

4.4. Movement between Industries

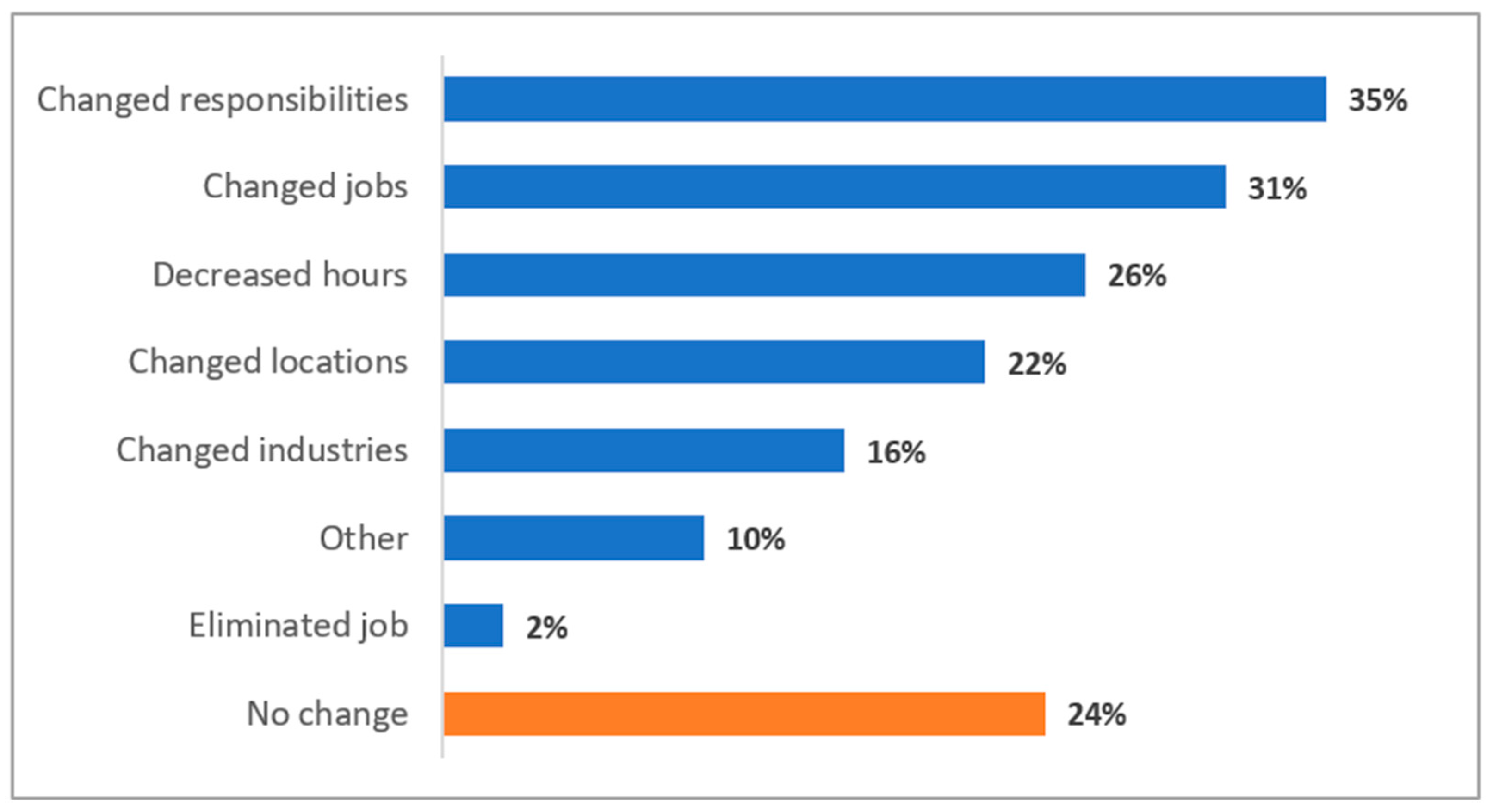

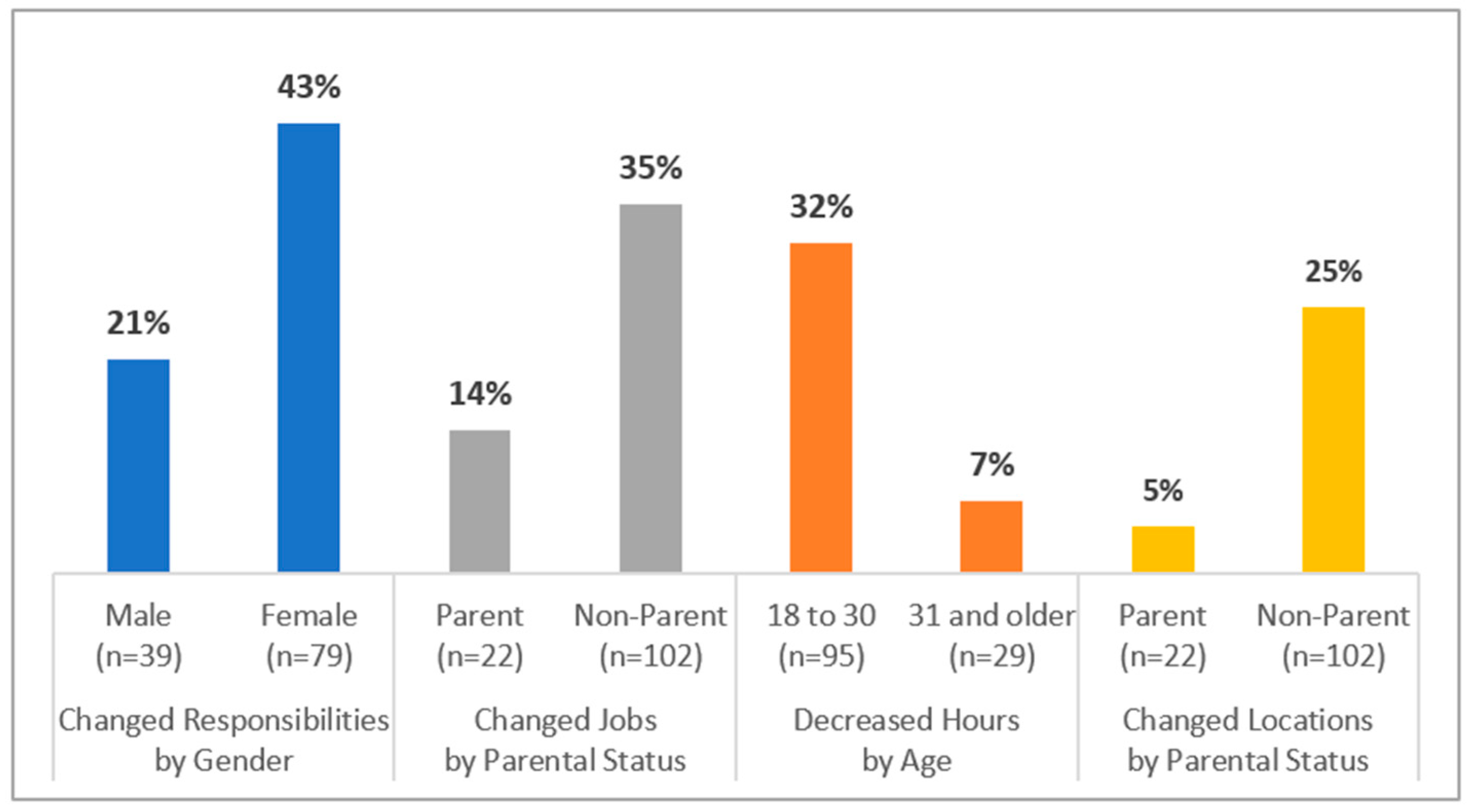

4.5. Impact of COVID-19 on Current Employment

4.6. Planned Employment over Summer/Fall

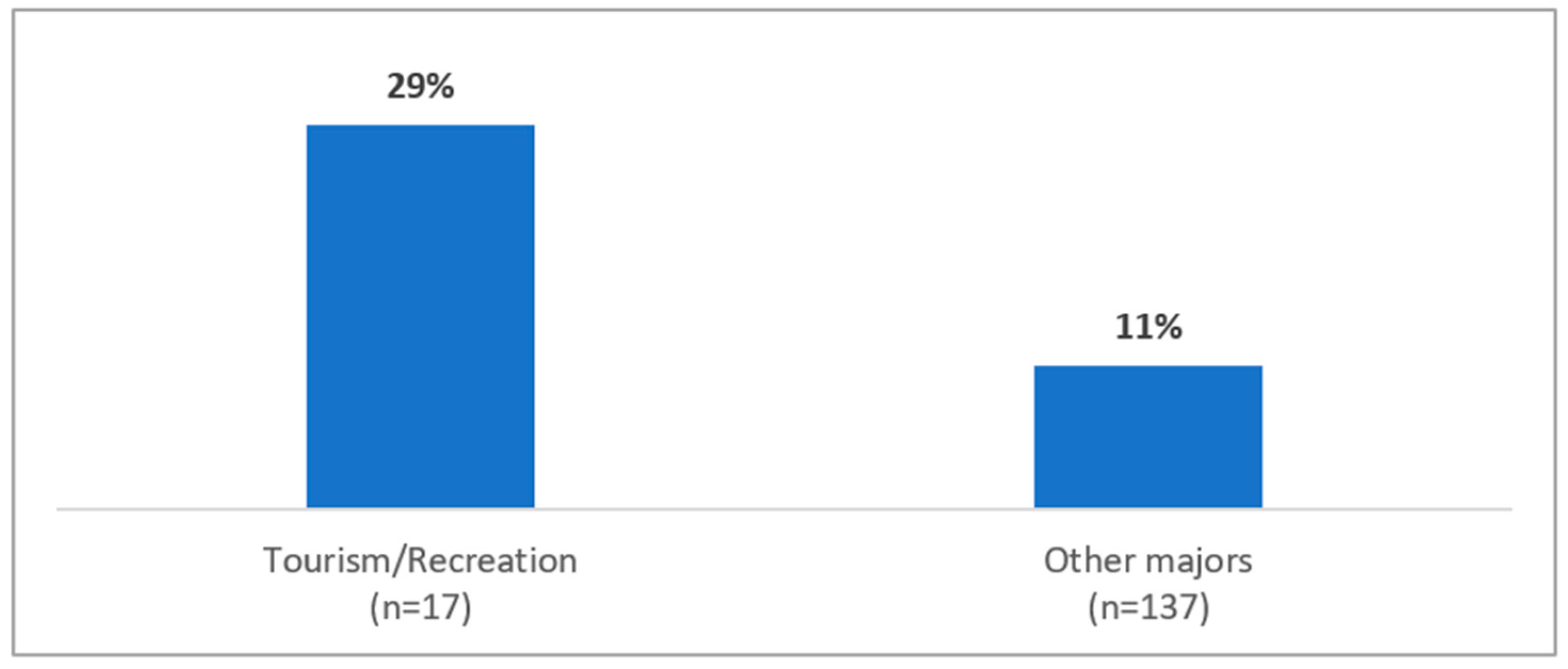

4.7. Incentives for Working in the Tourism Industry

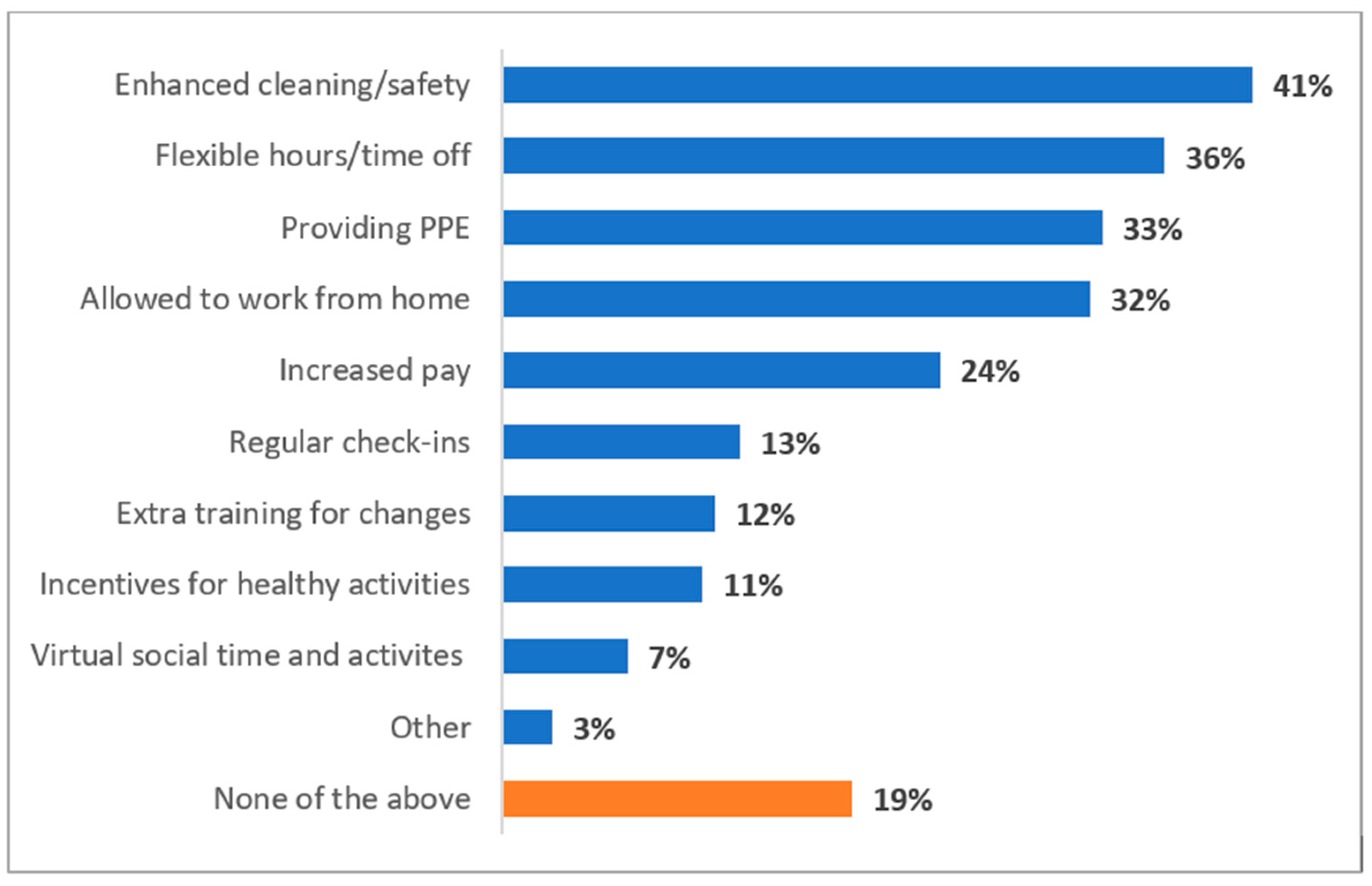

4.8. Industry Support during COVID-19

4.9. USM Support during COVID-19

5. Discussions

6. Practical Implications

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- In what industry were you primarily employed at the onset of COVID-19? (Report the job at which you spent the most hours).

- □

- USM (job, work study, research assistant, etc.)

- □

- Tourism/hospitality/recreation-based job (restaurant/bar, lodging, attractions, beaches, retail catering to visitors, activity-based business such as guiding and tours, transportation catering to visitors, local/state parks, etc.)

- □

- Non-tourism/hospitality/recreation-based job

- □

- I was not employed at the onset of COVID-19

- How was this employment impacted by COVID-19? (Select all that apply.)

- □

- Lost job

- □

- Laid off or furloughed

- □

- Reduced hours

- □

- Increased hours

- □

- Task, responsibility, or focus change

- □

- Voluntarily left

- □

- Other (Please describe.) ________________________________________________

- Are you currently employed?

- □

- Yes, at the same job

- □

- Yes, at a new/different job

- □

- No

- In what industry are you primarily employed currently?

- □

- USM (job, work study, research assistant, etc.)

- □

- Tourism/hospitality/recreation-based job (restaurant/bar, lodging, attractions, beaches, retail catering to visitors, activity-based business such as guiding and tours, transportation catering to visitors, local/state parks, etc.)

- □

- Non-tourism/hospitality/recreation-based job

- How has your employment changed due to COVID-19?

- □

- Changed jobs

- □

- Changed locations

- □

- Changed industries

- □

- Changed responsibilities within my job

- □

- Decreased hours

- □

- Eliminated job

- □

- Other (Please describe.) ________________________________________________

- □

- No change

- Do you plan to [enter into any employment/stay employed] this summer or fall?

- □

- Yes

- □

- Yes, if the pandemic is over [this answer option displayed to those not currently employed]

- □

- No

- Do you plan to [enter into employment/stay employed] in the tourism/recreation industry (restaurant/bar, lodging, attractions, beaches, retail catering to visitors, activity-based business such as guiding and tours, transportation catering to visitors, local/state parks, etc.) this summer or fall?

- □

- Yes

- □

- Yes, if the pandemic is over [this answer option displayed to those not currently employed]

- □

- No

- What incentives [might] encourage you to work in the tourism/recreation industry (restaurant/bar, lodging, attractions, beaches, retail catering to visitors, activity-based business such as guiding and tours, transportation catering to visitors, local/state parks, etc.)? (Select all that apply.)

- □

- Enhanced cleaning/public health measures

- □

- Increased ability to socialize and interact with others

- □

- Higher pay

- □

- More regular hours

- □

- The end of COVID-19

- □

- Other (Please describe.) _____________________________________

- □

- None of the above

- How has your industry supported you during the COVID-19 pandemic? (Select all that apply.)

- □

- Allowed to work from home

- □

- Enhanced cleaning/safety measures

- □

- Providing personal protective equipment

- □

- Increased pay

- □

- Flexible hours/time off

- □

- Virtual social time or other non-work activities

- □

- Extra training for changes in workplace

- □

- Offering time, money, or incentives for healthy programs/activities/apps

- □

- Regular check-ins

- □

- Other (Please describe.) _______________________________________

- □

- None of the above

- How has USM supported you during the COVID-19 pandemic? (Select all that apply.)

- □

- Kept me up to date on changes within my industry

- □

- Helped me to find employment during pandemic

- □

- Academic support

- □

- Emotional support

- □

- Provided trainings within my industry/field

- □

- Provided opportunities to make connections/networking

- □

- Offered me flexibility

- □

- Other (Please describe.) _______________________________________

- □

- None of the above

- Do you want to add anything? For example, COVID-19 pandemic impacts on your past/current/future employment, lessons learned, etc.? [open-ended response]

- What is your current gender identity?

- □

- Male

- □

- Female

- □

- Other ___________________________________________________

- □

- Prefer not to say

- What is your current age?

- □

- 18–30 years old

- □

- 31–45 years old

- □

- 46–60 years old

- □

- 60+ years old

- What is your race?

- □

- Asian/Pacific Islander

- □

- Black or African American

- □

- Native American or Alaska Native

- □

- White

- □

- From multiple races

- □

- Other ___________________________________________

- □

- Prefer not to say

- Do you consider yourself Latino or Hispanic?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- □

- Prefer not to say

- Are you…?

- □

- A commuter

- □

- Living on campus

- Are you a parent, or are you the primary caretaker for a parent or other family member(s)?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- Are you a first-generation college student?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- For how many years have you been pursuing your degree?

- □

- 1

- □

- 2

- □

- 3

- □

- 4

- □

- 5

- □

- >5

- What is your major? [see Appendix B for list of majors]

Appendix B

| Types of Majors | Major | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arts, Humanities, & Social Sciences | Art | 5 | 3% |

| Economics | 1 | 1% | |

| English | 2 | 1% | |

| History | 3 | 2% | |

| Liberal Studies-Humanities | 1 | 1% | |

| Media Studies | 5 | 3% | |

| Music | 3 | 2% | |

| Philosophy | 1 | 1% | |

| Political Science | 2 | 1% | |

| Social & Behavioral Sciences | 6 | 4% | |

| Theatre | 1 | 1% | |

| Business | Accounting | 3 | 2% |

| Business Administration | 12 | 8% | |

| Marketing | 2 | 1% | |

| Sports Management | 1 | 1% | |

| Health/Nursing | Athletic Training | 1 | 1% |

| Exercise Science | 5 | 3% | |

| Health Sciences | 9 | 6% | |

| Nursing | 11 | 7% | |

| Human/Public Service | Education | 3 | 2% |

| Environmental Planning & Policy | 2 | 1% | |

| Science & Technology | Biochemistry | 1 | 1% |

| Biology | 7 | 4% | |

| Cybersecurity | 3 | 2% | |

| Engineering | 4 | 3% | |

| Environmental Science | 1 | 1% | |

| Linguistics | 5 | 3% | |

| Mathematics | 1 | 1% | |

| Mechanical Engineering | 1 | 1% | |

| Physics | 1 | 1% | |

| Psychology | 5 | 3% | |

| Technology | 4 | 3% | |

| Tourism/Recreation | Recreation & Leisure Studies | 7 | 4% |

| Tourism & Hospitality | 10 | 6% | |

| Other/Undeclared | Other | 9 | 6% |

| Undeclared | 2 | 1% |

References

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee for the Coordination of Statistical Activities (CCSA). How COVID-19 Is Changing the World: A Statistical Perspective, Volume III. 2021. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/ccsa/documents/covid19-report-ccsa_vol3.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Harchandani, P.; Shome, S. Global Tourism and COVID-19: An Impact Assessment. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2021, 69, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, S.R.; Thrivikraman, J.K.; Noveck, N.; Romain, T.S.; Ludy, M.J.; Barnhart, L.; Tucker, R.M. Concerns of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Thematic perspectives from the United States, Asia, and Europe. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2021, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, T.; Mooney, S.K.; Robinson, R.N.S.; Solnet, D. COVID-19’s impact on the hospitality workforce—new crisis or amplification of the norm? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2813–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavosky, J.; Quin, Y.; Sargent, A. The gendered pandemic: The implications of COVID-19 for work and family. Sociol. Compass 2021, 15, e12881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, V. The State of Women’s Leadership in Five Statistics; The World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/11/un-women-2020-gender-equality/ (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Kochhar, R.; Barosso, A. Young Workers Likely to be Hard Hit as COVID-19 Strikes a Blow to Restaurants and Other Service Sector Jobs; (FACTANK: News in the Numbers); Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/27/young-workers-likely-to-be-hard-hit-as-covid-19-strikes-a-blow-to-restaurants-and-other-service-sector-jobs/ (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Dias, F.A.; Chance, J.; Buchanan, A. The motherhood penalty and the fatherhood premium in employment during COVID-19: Evidence from the United States. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2020, 69, 100542. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7431363/ (accessed on 29 January 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Current Employment Statistics—CES (National); U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/charts/employment-situation/otm-employment-change-by-industry-confidence-intervals.htm (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Bateman, N.; Ross, M. Why Has CVODI-19 Been Especially Harmful for Working Women? Brookings Gender Equality Series. 2020. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/essay/why-has-covid-19-been-especially-harmful-for-working-women/ (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Dashper, K. Mentoring for gender equality: Supporting female leaders in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 76, 38–44. Available online: https://doi-org.udel.idm.oclc.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102397 (accessed on 29 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, S.A. Mentors are Good. Sponsors are Better. The New York Times, 13 April 2013. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/14/jobs/sponsors-seen-as-crucial-for-womens-career-advancement.html?_r=0(accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Miller, R.K.; Washington, K. Travel & Tourism: Impact of the Pandemic Special Edition; Richard K. Miller & Associates: Miramar, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Vaccines. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-vaccines?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI_ePIxZuM9QIVIgJMCh3IhAC2EAAYAyAAEgKm3_D_BwE&topicsurvey=v8kj13) (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- The Coronavirus Pandemic. The New York Times, 2022. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/covid-cases.html(accessed on 11 May 2022).

- USM Office of Public Affairs. USM Receives Approval to Offer Bachelor’s Degree in Tourism and Hospitality. 2012. Available online: https://usm.maine.edu/publicaffairs/usm-receives-approval-offer-bachelors-degree-tourism-and-hospitality (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- McDonnell, J. Off Campus: University and City Can Be Partners in Economic Development. 2012. Available online: https://www.pressherald.com/2012/11/12/university-and-city-can-be-partners-in-economic-development_2012-11-12/ (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Gabe, T.; Crawley, A. Economic Contribution of Maine’s Hospitality Sector; School of Economics Staff Paper #635; University of Maine: Orono, ME, USA, 2019; Available online: https://regionaleconmodellinghome.files.wordpress.com/2019/11/hospitality-impact-2019-final-soe-staff-paper-copy.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Maine Office of Tourism. Economic Impact, Maine Tourism Highlights-2019. Available online: https://motpartners.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2019_Maine_Tourism_Highlights.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Maine Office of Tourism. Economic Impact, Maine Tourism Highlights-2020. Available online: https://motpartners.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/2020_Maine_Tourism_Highlight.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Liu, C.H.; Pinder-Amaker, S.; Hahm, H.C.; Chen, J.A. Priorities for addressing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health. J. Am. Col. Health 2020, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.; Chhetri, R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. High. Educ. Future 2021, 8, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmingham, W.C.; Wadsworth, L.L.; Lassetter, J.H.; Graff, T.C.; Lauren, E.; Hung, M. COVID-19 lockdown: Impact on college students’ lives. J. Am. Col. Health 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USM. Common Data Set (2021–2022). Available online: https://usm.maine.edu/department-analysis-applications-institutional-research/common-data-set-2021–2022 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Mahoney, M. The Chronicle of Higher Education, Who Is a First-Generation Student? 2021. Available online: https://connect.chronicle.com/rs/931-EKA-218/images/WhoisFirstGen_Ascendium_Explainerv3.pdf?aliId=eyJpIjoiRzlcLzJaT2l0WmpicFhlQzIiLCJ0Ijoid3g0VFwvWGJ3QUp2VUQ3ZG5mSjA1TVE9PSJ9 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- USM Office of Public Affairs. USM Welcomes Largest Cohort of Promise Scholar. 2021. Available online: https://usm.maine.edu/publicaffairs/usm-welcomes-largest-cohort-promise-scholars-program-moves-mountains (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Goeldner, C.R.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC). Economic Impact Reports. 2021. Available online: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- UNWTO. 2020 A Year in Review. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/covid-19-and-tourism-2020 (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- International Trade Administration (ITA); National Travel and Tourism Office. Fast Facts. 2019. Available online: https://travel.trade.gov/outreachpages/inbound.general_information.inbound_overview.asp (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Outdoor Industry Association—OIA. The Outdoor Recreation Economy (Report); Outdoor Industry Association-OIA: Boulder, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Outdoor Industry Association—OIA. Advocacy. 2020. Available online: https://outdoorindustry.org/advocacy/ (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Outdoor Industry Association—OIA. 2021 Outdoor Participation Trends Report. 2021. Available online: https://outdoorindustry.org/resource/2021-outdoor-participation-trends-report/ (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Maine Office of Tourism Highlights. 2018. Available online: https://motpartners.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/2018_MAINE_GovConf_HighlightSheet.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Gabe, T.; Crawley, A. Early Impacts of COVID-19 on Maine’s Hospitality Sector in 2020; School of Economics University of Maine: Orono, ME, USA, 2020; Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/102678/1/MPRA_paper_102678.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Gabe, T.; Crawley, A. Impacts of COVID-19 on Maine’s Hospitality Sector; School of Economics University of Maine: Orono, ME, USA, 2020; Available online: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1053&context=c19_teach_doc (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Valigra, L. Maine Hospitality Industry Anticipates Future with Fewer Workers but More Training. Bangor Daily News, 15 September 2021. Available online: https://bangordailynews.com/2021/09/15/business/maine-hospitality-industry-anticipates-future-with-fewer-workers-but-more-training/(accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Trotter, B. Maine’s Summer Tourist Season Managed to Beat Low Expectations After a Dismal Spring. Bangor Daily News, 14 September 2020. Available online: https://bangordailynews.com/2020/09/14/business/maines-summer-tourist-season-managed-to-beat-low-expectations-after-a-dismal-spring/(accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Michaud, T.; Metcalf, C.; Bampton, M. Understanding changing consumer behavior within a destination from social media. Int. J. Gaming. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 10, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Pineo, J. The Maine Monitor. Help Needed! Maine Tourism Faces too Much Business and too Little Staff. 2021. Available online: https://www.themainemonitor.org/help-needed-maine-tourism-faces-too-much-business-and-too-little-staff/ (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (U.S. BEA). Outdoor Recreation. 2022. Available online: https://www.bea.gov/data/special-topics/outdoor-recreation (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Cheng, D.X.; Alcántara, L. Assessing working students’ college experiences: A grounded theory approach. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2007, 32, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, E.F.; Bilges, D.C.; Shabazz, S.T.; Miller, R.; Morote, E.S. To work or not to work: Student employment, resiliency, and institutional engagement of low-income, first-generation college students. J. Stud. Fin. Aid 2012, 42, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remenick, L.; Bergman, M. Support for working students: Considerations for higher education institutions. J. Contin. High. Educ. 2021, 69, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucejo, E.M.; French, J.; Araya, M.P.U.; Zafar, B. The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. J. Pub. Econ. 2020, 191, 104271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.K.; Hoyt, L.T.; Dull, B. A Descriptive study of COVID-19–related experiences and perspectives of a national sample of college students in spring 2020. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, K. COVID-19 Pandemic: Financial Impacts on Postsecondary Students in Canada; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, R.H.; Dadaczynski, K.; Okan, O.; McCaffery, K.J.; Pickles, K. Psychological wellbeing and academic experience of University students in Australia during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odriozola-González, P.; Planchuelo-Gómez, Á.; Irurtia, M.J.; de Luis-García, R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, K.; Hurley, P.; Macklin, S. COVID-19, Employment Stress and Student Vulnerability in Australia; Mitchell Institute for Education and Health Policy, Victoria University: Footscray, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey and Company. COVID-19’s Impact on Women’s Employment, McKinsey Insights. 2021. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/seven-charts-that-show-covid-19s-impact-on-womens-employment (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Hite, L.M.; McDonald, K.S. Careers after COVID-19: Challenges and changes. Hum. Res. Dev. Int. 2020, 23, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristovnik, A.; Keržič, D.; Ravšelj, D.; Tomaževič, N.; Umek, L. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N.; Khosa, S. Disaster resiliency and culture of preparedness for university and college campuses. Adm. Soc. 2013, 45, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.A.; Karabas, I. Glamping after the coronavirus pandemic. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 21, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, T.B.; Jamal, T. An integrated approach to “sustainable community-based tourism”. Sustainability 2016, 8, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dangi, T.B.; Petrick, J.F. Enhancing the role of tourism governance to improve collaborative participation, responsiveness, representation and inclusion for sustainable community-based tourism: A case study. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2021, 7, 1029–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic | Response | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (98% responding) | Male | 33% |

| Female | 65% | |

| Other | 2% | |

| Age (99% responding) | 18–30 | 76% |

| 31–45 | 13% | |

| 46–60 | 9% | |

| ≥60 | 2% | |

| Race (95% responding) | White | 85% |

| Persons of Color | 15% | |

| Commuter/Residential (100% responding) | Commuters | 84% |

| Residential | 16% | |

| Parenting & Caretaking for Family (100% responding) | Yes | 16% |

| No | 84% | |

| First Generation Students (99% responding) | Yes | 36% |

| No | 64% | |

| Years as a Student (98% responding) | One year | 18% |

| Two years | 20% | |

| Three years | 17% | |

| Four years | 20% | |

| Five years | 4% | |

| Six years | 20% | |

| Major * (98% responding) | Arts, Humanities, & Social Science | 19% |

| Business | 11% | |

| Health/Nursing | 17% | |

| Human/Public Services | 14% | |

| Science & Technology | 21% | |

| Tourism/Recreation | 11% | |

| Other/Undeclared | 7% |

| Employment | COVID-19 Onset Employment (n = 160) | Current Employment (n = 160) |

|---|---|---|

| Tourism | 25% | 22% |

| Non-tourism | 44% | 42% |

| USM | 16% | 14% |

| Not employed | 15% | 22% |

| Industry Type | Most Recent Employment (n = 160) |

|---|---|

| Tourism | 26% |

| Non-tourism | 48% |

| USM | 17% |

| Not employed | 9% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dangi, T.B.; Michaud, T.; Dumont, R.; Wheeler, T. Differential Impacts of COVID-19 on College Student Tourism Jobs: Insights from Vacationland-Maine, USA. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 509-535. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3020032

Dangi TB, Michaud T, Dumont R, Wheeler T. Differential Impacts of COVID-19 on College Student Tourism Jobs: Insights from Vacationland-Maine, USA. Tourism and Hospitality. 2022; 3(2):509-535. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3020032

Chicago/Turabian StyleDangi, Tek B., Tracy Michaud, Robyn Dumont, and Tara Wheeler. 2022. "Differential Impacts of COVID-19 on College Student Tourism Jobs: Insights from Vacationland-Maine, USA" Tourism and Hospitality 3, no. 2: 509-535. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3020032

APA StyleDangi, T. B., Michaud, T., Dumont, R., & Wheeler, T. (2022). Differential Impacts of COVID-19 on College Student Tourism Jobs: Insights from Vacationland-Maine, USA. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(2), 509-535. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3020032