Using Systems Thinking to Improve Tourism and Hospitality Research Quality and Relevance: A Critical Review and Conceptual Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Pragmatic research which has both high rigour and high relevance and is the goal of research in applied fields;

- -

- Popularist research which has low rigour but high relevance, often emerging in response to new trends or unexpected changes in areas of interest such as the 2020 COVID 19 pandemic;

- -

- Pedantic research which has high rigour and low relevance with a focus on developing more exact and precise, although not necessarily valid, measurement instruments; and

- -

- Puerile research which has neither relevance nor rigour.

2. Systems Thinking

- -

- Causal relationships expressed as interconnections between elements:

- -

- Elements or components which correspond to the main institutions or actors in the system;

- -

- Feedback loops that connect the elements and relationships to outcomes of relevance to the problem being researched and managed;

- -

- Emergent properties which are new and often surprising elements that emerge from changes in the system;

- -

- External forces that exert pressure on the system; and

- -

3. Aims and Approach of This Paper

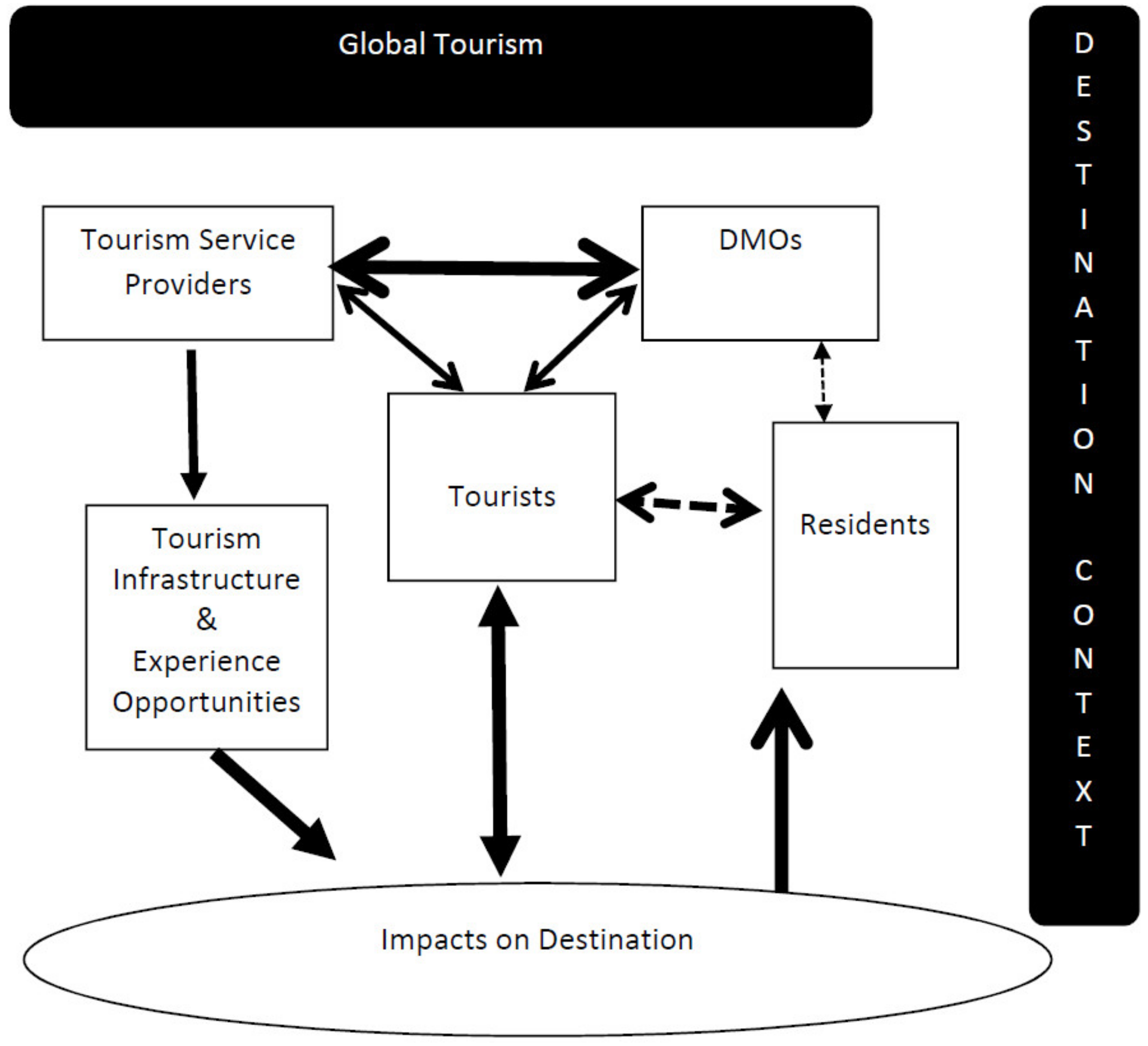

4. Taking a Systems Approach to the Social Impacts of Tourism

- -

- they are typically published in or as books providing a more descriptive rather than analytic overview of tourism impacts;

- -

- understanding tourism impacts is seen as a critical pathway to analysing tourism and sustainability;

- -

- tourism impacts are linked to features of tourism and tourist actions;

- -

- mostly links between tourism and tourists and impacts are focussed at the destination level; and

- -

5. Review of Research into the Social Impacts of Tourism

6. Taking a Systems Approach to Psychology for Guest Engagement with Sustainability in Hotels and Restaurants

7. Review of Research Using Psychological Concepts to Examine Guest Engagement with Sustainability in Hotels

8. Conclusions and Implications for Improving Tourism Research

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. References Examined for the Critical Review Components

Appendix A.1. References January 2018 to April 2020 on Resident Attitudes Towards/Perceptions of Tourism and Its Impacts (Not Including QoL or Similar Concepts)

- Alrwajfah, M.M.; Almeida-García, F.; Cortés-Macías, R. Residents’ perceptions and satisfaction toward tourism development: A case study of Petra Region, Jordan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1907.

- Cardoso, C.; Silva, M. Residents’ perceptions and attitudes towards future tourism development. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, doi:10.1108/WHATT-07-2018-0048.

- Eusébio, C.; Vieira, A.L.; Lima, S. Place attachment, host–tourist interactions, and residents’ attitudes towards tourism development: The case of Boa Vista Island in Cape Verde. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 890–909.

- Gannon, M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Taheri, B. Assessing the mediating role of residents’ perceptions toward tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2020, doi:10.1177/0047287519890926.

- Litvin, S.W.; Smith, W.W.; McEwen, W.R. Not in my backyard: Personal politics and resident attitudes toward tourism. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 674–685.

- Liu, X.R.; Li, J.J. Host perceptions of tourism impact and stage of destination development in a developing country. Sustainability 2018, 10, doi:10.3390/su10072300.

- Martín, H.S.; De los Salmones Sanchez, M.M.G.; Herrero, Á. Residents’ attitudes and behavioural support for tourism in host communities. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 231–243.

- Peters, M.; Chan, C.S.; Legerer, A. Local perception of impact-attitudes-actions towards tourism development in the Urlaubsregion Murtal in Austria. Sustainability 2018, 10, doi:10.3390/su10072360.

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ramayah, T. Urban vs. rural destinations: Residents’ perceptions, community participation and support for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 147–158.

- Rua, S.V. Perceptions of tourism: A study of residents’ attitudes towards tourism in the city of Girona. J. Tour. Anal. 2020, 27, 165–184.

- Shtudiner, Z.E.; Klein, G.; Kantor, J. How religiosity affects the attitudes of communities towards tourism in a sacred city: The case of Jerusalem. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 167–179.

- Thyne, M.; Watkins, L.; Yoshida, M. Resident perceptions of tourism: The role of social distance. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 256–266.

- Tsaur, S.H.; Yen, C.H.; Teng, H.Y. Tourist–resident conflict: A scale development and empirical study. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 152–163.

- Wassler, P.; Nguyen, T.H.H.; Schuckert, M. Social representations and resident attitudes: A multiple-mixed-method approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102740.

- Yang, J.; Ryan, C.; Zhang, L. Social conflict in communities impacted by tourism. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 82–93.

- Zamani-Farahani, H.; Musa, G. The relationship between Islamic religiosity and residents’ perceptions of socio-cultural impacts of tourism in Iran: Case studies of Sare’in and Masooleh. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 802–814.

Appendix A.2. References 2016–2020 on Tourism Impacts on Resident QoL/Wellbeing and Related Concepts

- Bimonte, S.; Faralla, V. Does residents’ perceived life satisfaction vary with tourist season? A two-step survey in a Mediterranean destination. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 199–208.

- Croes, R.; Ridderstaat, J.; Van Niekerk, M. Connecting quality of life, tourism specialization, and economic growth in small island destinations: The case of Malta. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 212–223.

- Eslami, S.; Khalifah, Z.; Mardani, A.; Streimikiene, D.; Han, H. Community attachment, tourism impacts, quality of life and residents’ support for sustainable tourism development. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 1061–1079.

- Eusebio, C.; Carneiro, M. Impact of tourism on residents’ quality of life. In Best Practices in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management; Campón-Cerro, A.M., Hernández-Mogollón, J.M., Folgado-Fernández, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 133–158.

- Hanafiah, M.H.; Azman, I.; Jamaluddin, M.R.; Aminuddin, N. Responsible tourism practices and quality of life: Perspective of Langkawi Island communities. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 222, 406–413.

- Konovalov, E.; Murphy, L.; Moscardo, G. An Exploration of Links between Levels of Tourism Development and Impacts on the Social Facet of Residents’ Quality of Life. In Best Practices in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management; Campón-Cerro, A.M., Hernández-Mogollón, J.M., Folgado-Fernández, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 77–107.

- Li, R.; Peng, L.; Deng, W. Resident Perceptions toward Tourism Development at a Large Scale. Sustainability 2019, 11, doi:10.3390/su11185074.

- Liang, Z.X.; Hui, T.K. Residents’ quality of life and attitudes toward tourism development in China. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 56–67.

- Mathew, P.V.; Sreejesh, S. Impact of responsible tourism on destination sustainability and quality of life of community in tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 83–89.

- Moscardo, G.; Konovalov, E.; Murphy, L.; McGehee, N.G.; Schurmann, A. Linking tourism to social capital in destination communities. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 286–295.

- Naidoo, P.; Sharpley, R. Local perceptions of the relative contributions of enclave tourism and agritourism to community well-being: The case of Mauritius. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 16–25.

- Porras-Bueno, N.; Plaza-Meijia, M.; Vargas-Sanchez, A. Quality of life and perceptions of the effects of tourism. In Best Practices in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management; Campón-Cerro, A.M., Hernández-Mogollón, J.M., Folgado-Fernández, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 109–132.

- Pratt, S.; McCabe, S.; Movono, A. Gross happiness of a ‘tourism’ village in Fiji. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 26–35.

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.; Uysal, M. Social involvement and park citizenship as moderators for quality-of-life in a national park. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 341–361.

- Ridderstaat, J.; Croes, R.; Nijkamp, P. The tourism development–quality of life nexus in a small island destination. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 79–94.

- Rivera, M.; Croes, R.; Lee, S.H. Tourism development and happiness: A residents’ perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 5–15.

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Huang, J. Effects of destination social responsibility and tourism impacts on residents’ support for tourism and perceived quality of life. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 1039–1057.

- Tichaawa, T.M.; Moyo, S. Urban resident perceptions of the impacts of tourism development in Zimbabwe. Bull. Geogr. Socioecon. Ser. 2019, 43, 25–44.

- Vogt, C.; Jordan, E.; Grewe, N.; Kruger, L. Collaborative tourism planning and subjective well-being in a small island destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 36–43.

- Woo, E.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. Tourism impact and stakeholders’ quality of life. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 260–286.

- Yu, C.P.; Cole, S.T.; Chancellor, C. Resident support for tourism development in rural midwestern (USA) communities: Perceived tourism impacts and community quality of life perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 802.

Appendix A.3. References Hospitality Guest Compliance with Sustainability Programs

- Agag, G. Understanding the determinants of guests’ behaviour to use green P2P accommodation. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3417–3446.

- Baker, M.A.; Davis, E.A.; Weaver, P.A. Eco-friendly attitudes, barriers to participation, and differences in behavior at green hotels. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 55, 89–99.

- Balaji, M.S.; Jiang, Y.; Jha, S. Green hotel adoption: a personal choice or social pressure? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3287–3305.

- Blose, J.E.; Mack, R.W.; Pitts, R.E. The influence of message framing on hotel guests’ linen-reuse intentions. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2015, 56, 145–154.

- Chang, H.S.; Huh, C.; Lee, M.J. Would an energy conservation nudge in hotels encourage hotel guests to conserve? Cornell Hosp. Q. 2015, 57, 172–183.

- Chen, H.; Bernard, S.; Rahman, I. Greenwashing in hotels: A structural model of trust and behavioral intentions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 326–335.

- Chen, H.; Jai, T.M. Waste less, enjoy more: forming a messaging campaign and reducing food waste in restaurants. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 19, 495–520.

- Choi, H.; Jang, J.; Kandampully, J. Application of the extended VBN theory to understand consumers’ decisions about green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 87–95.

- Cvelbar, L.; Grün, B.; Dolnicar, S. “To clean or not to clean?” Reducing daily routine hotel room cleaning by letting tourists answer this question for themselves. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 220–229.

- Dharmesti, M.; Merrilees, B.; Winata, L. “I’m mindfully green”: Examining the determinants of guest pro-environmental behaviors (PEB) in hotels. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 830–847.

- Dimara, E.; Manganari, E.; Skuras, D. Don’t change my towels please: Factors influencing participation in towel reuse programs. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 425–437.

- Dolnicar, S.; Cvelbar, L.K.; Grun, B. Do pro-environmental appeals trigger pro-environmental behavior in hotel guests? J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 988–997.

- Elhoushy, S. Consumers’ sustainable food choices: Antecedents and motivational imbalance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102554.

- Giebelhausen, M.; Chun, H.; Cronin, J.; Hult, G. Adjusting the warm-glow thermostat: How incentivizing participation in voluntary green programs moderates their impact on service satisfaction. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 56–71.

- Giebelhausen, M.; Lawrence, B.; Chun, H.; Hsu, L. The Warm Glow of Restaurant Checkout Charity. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 58, 329–341.

- Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V.; Cialdini, R.B. Invoking social norms: A social psychology perspective on improving hotels’ linen-reuse programs. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2007, 48, 145–150.

- Grazzini, L.; Rodrigo, P.; Aiello, G.; Viglia, G. Loss or gain? The role of message framing in hotel guests’ recycling behaviour. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1944–1966.

- Han, H. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177.

- Han, H. Theory of green purchase behavior (TGPB): A new theory for sustainable consumption of green hotel and green restaurant products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2815–2828.

- Han, H.; Chen, C.; Lho, L.H.; Kim, H.; Yu, J. Green Hotels: Exploring the Drivers of Customer Approach Behaviors for Green Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, doi:10.3390/su12219144.

- Han, H.; Chua, B.L.; Hyun, S.S. Eliciting customers’ waste reduction and water saving behaviors at a hotel. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102386.

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. What influences water conservation and towel reuse practices of hotel guests? Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 87–97.

- Han, H.; Moon, H.; Lee, H. Excellence in eco-friendly performance of a green hotel product and guests’ proenvironmental behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–10.

- Han, H.; Yoon, H. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33.

- Hanks, L.; Zhang, L.; Line, N.; McGinley, S. When less is more: Sustainability messaging, destination type, and processing fluency. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 58, 34–43.

- Hwang, K.; Lee, B. Pride, mindfulness, public self-awareness, affective satisfaction, and customer citizenship behaviour among green restaurant customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 169–179.

- Kallbekken, S.; Saelen, H. ‘Nudging’ hotel guests to reduce food waste as a win–win environmental measure. Econ. Lett. 2013, 119, 325–327.

- Kang, K.H.; Stein, L.; Heo, C.Y.; Lee, S. Consumers’ willingness to pay for green initiatives of the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 564–572.

- Kim, S.B.; Kim, D.Y. The effects of message framing and source credibility on green messages in hotels. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 64–75.

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L.; Zhang, L. Sustainability communication: The effect of message construals on consumers’ attitudes towards green restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 143–151.

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L.; Zhang, L. Birds of a feather donate together: Understanding the relationship between the social servicescape and CSR participation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 102–110.

- Lu, L.; Chi, C.G.Q. Examining diners’ decision-making of local food purchase: The role of menu stimuli and involvement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 113–123.

- Mair, J.; Bergin-Seers, S. The effect of interventions on the environmental behaviour of Australian motel guests. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2010, 10, 255–268.

- Nicolau, J.L.; Guix, M.; Hernandez-Maskivker, G.; Molenkamp, N. Millennials’ willingness to pay for green restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102601.

- Nimri, R.; Patiar, A.; Kensbock, S.; Jin, X. Consumers’ intention to stay in green hotels in Australia: Theorization and implications. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 149–168.

- Olya, H.G.; Bagheri, P.; Tümer, M. Decoding behavioural responses of green hotel guests. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2509–2525.

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D. Predicting green hotel behavioral intentions using a theory of environmental commitment and sacrifice for the environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 107–116.

- Shin, Y.H.; Im, J.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. Locally sourced restaurant: Consumers willingness to pay. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2018, 21, 68–82.

- Shin, Y.H.; Im, J.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. The theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model approach to consumer behavior regarding organic menus. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 21–29.

- Tanford, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, E.J. Priming social media and framing cause-related marketing to promote sustainable hotel choice. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1762–1781.

- Tang, C.M.F.; Lam, D. The role of extraversion and agreeableness traits on Gen Y’s attitudes and willingness to pay for green hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 607–623.

- Teng, C.; Chang, J. Effects of temporal distance and related strategies on enhancing customer participation intention for hotel eco-friendly programs. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 92–99.

- Tussyadiah, I.; Miller, G. Nudged by a robot: Responses to agency and feedback. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, doi:10.1016/j.annals.2019.102752.

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B.; Kumar, S. Values and ascribed responsibility to predict consumers’ attitude and concern towards green hotel visit intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 206–216.

- Wu, L.; Gao, Y.; Mattila, A.S. The impact of fellow consumers’ presence, appeal type, and action observability on consumers’ donation behaviors. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 58, 203–213.

- Yadav, R.; Balaji, M.S.; Jebarajakirthy, C. How psychological and contextual factors contribute to travelers’ propensity to choose green hotels? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 385–395.

- Zhang, L. How effective are our CSR messages? The moderating role of processing flouncy and construal level. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 56–62.

References

- Tribe, J.; Liburd, J.J. The tourism knowledge system. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, T.S.; Sandstrom, J.; Swanger, N. Bridging the gap. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1691–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, O.; Hahn, H.J.; Peterson, S.L. Research–Practice Gap in Applied Fields: An Integrative Literature Review. Hum. Resource Dev. Rev. 2017, 16, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.; Herriot, P.; Hodgkinson, G.P. The practitioner-researcher divide in Industrial, Work and Organizational (IWO) psychology. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2001, 74, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Page, S.J. Following the impact factor. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagioli, M.; Kenney, M.; Martin, B.R. Academic misconduct, misrepresentation and gaming. Res. Policy 2018, 48, 408–413. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, M.A.; Roy, S. Academic research in the 21st century. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2017, 34, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, D.B.; Kovács, G.; Spens, K. Questionable research practices in academia. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2018, 30, 101–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.; Groesser, S.N. Reframing the relevance of research to practice. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanberg, M. Guidelines for establishing practical relevance in logistics and supply chain management research. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2020, 50, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartunek, J.M.; Rynes, S.L. Academics and practitioners are alike and unlike. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1181–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, G.P.; Starkey, K. Not simply returning to the same answer over and over again. Br. J. Manag. 2011, 22, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichselgartner, J.; Kasperson, R. Barriers in the science-policy-practice interface. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, S.F. Information needs for building a foundation for enhancing sustainable tourism as a development goal. In A Research Agenda for Sustainable Tourism; McCool, S.F., Bosak, K., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Surveyer, A.; Elmqvist, T.; Gatzweiler, F.W.; Webb, R. Defining and advancing a systems approach for sustainable cities. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 23, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretter, A.; Ciolli, M.; Scolozzi, R. Governing mountain landscapes collectively. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Kennedy, S.; Philipp, F.; Whiteman, G. Systems thinking. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 866–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamim, S.R. Analyzing the Complexities of Online Education Systems. TechTrends 2020, 64, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inghels, D. Introduction to Modeling Sustainable Development in Business Processes; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baggio, J.A.; Baggio, R. Modelling and Simulations for Tourism and Hospitality: An Introduction; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baggio, R. Symptoms of complexity in a tourism system. Tour. Anal. 2008, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, R.; Scott, N.; Cooper, C. Improving tourism destination governance: A complexity science approach. Tour. Rev. 2010, 65, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, S.F.; Freimund, W.A.; Breen, C. Benefiting from complexity thinking. In Protected Area Governance and Management; Worboys, G.L., Lockwood, M., Kothari, A., Feary, S., Pulsford, I., Eds.; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2015; pp. 291–326. [Google Scholar]

- McCool, S.F.; Kline, J.D. A systems thinking approach for thinking and reflecting on sustainable recreation on public lands in an era of complexity, uncertainty, and change. In Igniting Research for Outdoor Recreation; Selin, S., Cerveny, L.K., Blahna, D.J., Miller, A.B., Eds.; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 2020; pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Abson, D.J.; Fischer, J.; Leventon, J.; Newig, J.; Lang, D. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 2017, 46, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.D.; Wade, J.P. A Definition of Systems Thinking. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 44, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, E.F. Making sense of the emerging conversation in evaluation about systems thinking and complexity science. Eval. Program Plan. 2016, 59, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.T.; Cook, C.N.; Redford, K.H.; Biggs, D.; Keene, M. Improving conservation practice with principles and tools from systems thinking and evaluation. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1531–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merali, Y.; Allen, P. Complexity and systems thinking. In The Sage Handbook of Complexity and Management; Allen, P., Maguire, S., Mckelvey, B., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2011; pp. 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G. Connecting people with experiences. In A Research Agenda for Sustainable Tourism; McCool, S., Bosak, K., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 70–89. [Google Scholar]

- Nisa, C.; Varum, C.; Botelho, A. Promoting sustainable hotel guest behavior. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 58, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briner, R.; Denyer, D. Systematic review and evidence synthesis as a practice and scholarship tool. In The Oxford Handbook of Evidence-Based Management; Rousseau, D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 112–129. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, B.; Cooper, C.; Ruhanen, L. The positive and negative impacts of tourism. In Global Tourism, 3rd ed.; Theobald, W., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, P. Tourism Impacts, Planning and Management; Butterworth-Heinemann: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rutty, M.; Gossling, S.; Hall, C.M. The global effects and impacts of tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Hall, C.M., Gossling, S., Scott, D., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 36–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, G.; Mathieson, A. Tourism: Change, Impacts, and Opportunities, 2nd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Konovalov, E.; Murphy, L.; Moscardo, G. An Exploration of Links between Levels of Tourism Development and Impacts on the Social Facet of Residents’ Quality of Life. In Best Practices in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management; Campón-Cerro, A.M., Hernández-Mogollón, J.M., Folgado-Fernández, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 77–107. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Ouyang, Z.; Nunkoo, R.; Wei, W. Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 306–333. [Google Scholar]

- Hadinejad, A.; Moyle, B.D.; Scott, N.; Kralj, A.; Nunkoo, R. Residents’ attitudes to tourism. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrill, R. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development. J. Plan. Lit. 2004, 18, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Smith, S.L.; Ramkissoon, H. Residents’ attitudes to tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deery, M.; Jago, L.; Fredline, L. Rethinking social impacts of tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, H.; Fyall, A.; Willis, C.; Page, S.; Ladkin, A.; Hemingway, A. Progress in tourism and destination wellbeing research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1830–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H.L. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.L.; Mattila, A.S.; Lee, S. A meta-analysis of behavioral intentions for environment-friendly initiatives in hospitality research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Encouraging hospitality guest engagement in responsible action. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakulin, T.J. Systems Approach to Tourism. Organizacija 2017, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.; Schmuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Deng, J.; Song, Z.; Ding, P. Research on environmental impacts of tourism in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2972–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.X.; Jin, M.; Shi, W. Tourism as an important impetus to promoting economic growth. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northcote, J.; Macbeth, J. Limitations of Resident Perception Surveys for Understanding Tourism Social Impacts. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2005, 30, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, C.; Silva, M. Residents’ perceptions and attitudes towards future tourism development. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Yen, C.H.; Teng, H.Y. Tourist–resident conflict. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 152–163. [Google Scholar]

- Thyne, M.; Watkins, L.; Yoshida, M. Resident perceptions of tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ryan, C.; Zhang, L. Social conflict in communities impacted by tourism. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Tourism and quality of life. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G.; Konovalov, E.; Murphy, L.; McGehee, N.G.; Schurmann, A. Linking tourism to social capital in destination communities. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridderstaat, J.; Croes, R.; Nijkamp, P. The tourism development–quality of life nexus in a small island destination. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.C. Disciplinary perspectives linked to middle range theory. In Middle Range Theory for Nursing, 4th ed.; Smith, M.J., Liehr, P.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P.J.; Dennis, A. Introduction: The Opposition of Structure and Agency. In Human Agents and Social Structures; Martin, P.J., Dennis, A., Eds.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2010; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, M.L.; Williams, P.; Spong, C.; Colla, R.; Oades, L.G. Systems informed positive psychology. J. Posit. Psychol. 2020, 15, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, M. Systems and theories. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology, 4th ed.; Weiner, B., Craighead, W.E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 971–972. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, T.L.; Stanton, M. Systems theories. In APA Handbook of Clinical Psychology; Norcross, J.C., VandenBos, G.R., Freedheim, D.K., Olatunji, B.O., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 213–239. [Google Scholar]

- Kerlinger, F.N.; Lee, H.B. Foundations of Behavioural Research, 4th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, D.; Dewall, C. Psychology in Everyday Life, 4th ed.; Macmillan Learning: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J. Dual-Process Theories. In The Routledge International Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning; Ball, L.J., Thompson, V.A., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, W. Habit in personality and social psychology. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 21, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D.; Twenge, J.M. Exploring Social Psychology, 8th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E. TED Talks and the Temptation of Big Ideas in Psychology. 2020. Available online: https://www.psychcongress.com/article/ted-talks-and-temptation-big-ideas-psychology (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Albarracin, D.; Shavitt, S. Attitudes and attitude change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 299–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElHaffar, G.; Durif, F.; Dubé, L. Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G.; Hughes, K. All Aboard! Strategies for Engaging Guests in Corporate Responsibility Programs. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleijenbergh, I.; Van Mierlo, J.; Bondarouk, T. Closing the gap between scholarly knowledge and practice: Guidelines for HRM action research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaz, A.; Hanney, S.; Borst, R.; O’Shea, A.; Kok, M. How to engage stakeholders in research: Design principles to support improvement. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Systems Thinking Features | Traditional Research Approaches |

|---|---|

| A focus on understanding the whole first as the key properties that emerge from the functioning of the whole system cannot be predicted from an analysis of its parts | A focus on understanding parts and assuming these build to a whole and therefore include key properties |

| A focus on the connectedness of actors and their actions | A focus on identifying, classifying and describing actors and their actions |

| Assumes nonlinear causality that contributes to continuous change through feedback loops | Assumes unidirectional causal connections between a single or small set of causes linked to a predicted or known effect |

| Is driven by a desire to change the system and emergent properties in some way | Is driven by a desire to describe the system |

| Simplifies complex systems using relatively simple models bounded by a specific problem or desired outcome | Builds increasingly complex models guided by a desire to describe in detail the processes considered to be of interest |

| Topic | Review Papers | Papers Published between Most Recent Review and End of April 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paper | No. of Papers Reviewed | ||

| Social Impacts of Tourism and Resident Attitudes | Deery et al., 2012 [44] | 41 | 16 |

| Gursoy et al., 2019 [39] | 28 | ||

| Hadinejad et al., 2019 [40] | 90 | ||

| Harrill 2004 [41] | 55 | ||

| Nunkoo et al., 2013 [42] | 140 | ||

| Sharpley 2014 [43] | 61 | ||

| QoL of Destination Communities | Hartwell et al., 2018 [45] | 40 | 21 |

| Uysal et al., 2016 [46] | 26 | ||

| Guest Engagement with Sustainability | Gao et al., 2016 [47] | 26 | 47 |

| Moscardo 2019b [48] | 19 | ||

| Nisa et al., 2017 [32] | 9 | ||

| Feature | Options | No. of Papers (Total 16) |

|---|---|---|

| Methodological Approach | Quantitative | 13 |

| Mixed method | 2 | |

| Qualitative | 1 | |

| Introductory claims about issues being addressed | Improving tourism sustainability/managing impacts | 13 |

| Supporting tourism development | 3 | |

| Systems Element Studied | Residents only | 13 |

| Other | 3 | |

| Recommendations | None | 7 |

| Changing resident attitude through marketing campaigns | 7 | |

| Changing tourism practices | 2 |

| Feature | Options | No. of Papers (Total 21) |

|---|---|---|

| Methodological Approach | Quantitative Only | 19 |

| Mixed Method/Qualitative | 2 | |

| Systems Element Studied | Residents Only | 8 |

| Other | 13 |

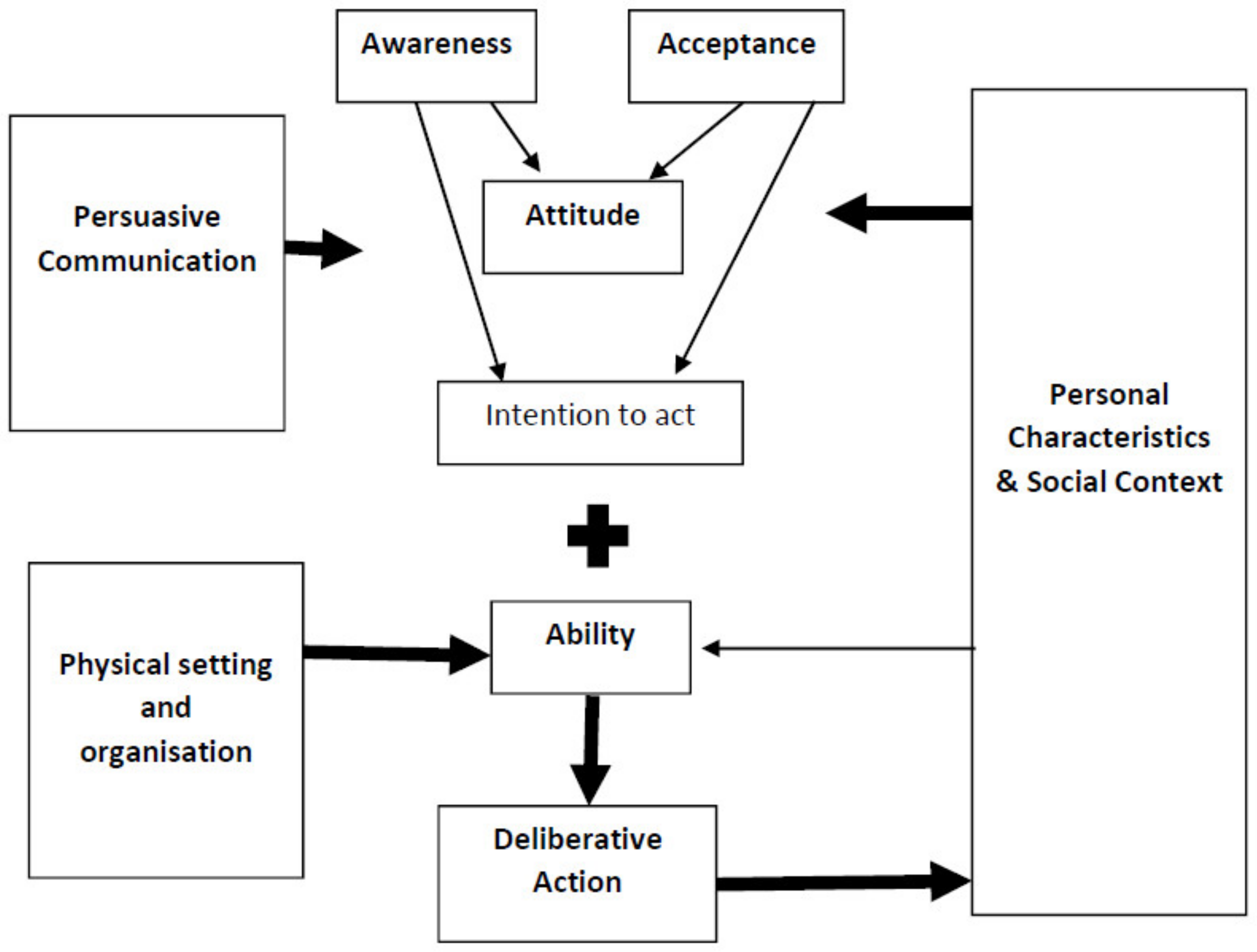

| Element | Features | Main Theories |

|---|---|---|

| Personal characteristics and social context | Personality Interest/motives Self-efficacy Values Social acceptability Previous experiences | Personality theory Social identity theory Value theory |

| Awareness | Knowledge of issue Knowledge of desirable actions | See persuasive communication |

| Acceptance | Belief actions will make a difference Trust in source of information Acceptance of responsibility Perceived social desirability or acceptability of action | Norm activation theory Trust |

| Attitude | Importance and accessibility of attitude | Attitude Theory |

| Intention | Intention | Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) |

| Ability | Perceived behavioural control over the action Self-efficacy Resources—time, money and physical infrastructure | Choice architecture |

| Persuasive communication | Communication source credibility, trustworthiness and likeability Communication medium accessibility and usage Type of information included Nature of argument presented Ease of comprehension | Elaboration Likelihood Model Mindfulness theory Prospect theory (framing) Construal theory (fluency) |

| Physical setting and context organisation | Infrastructure provided Administrative procedures | Choice Architecture |

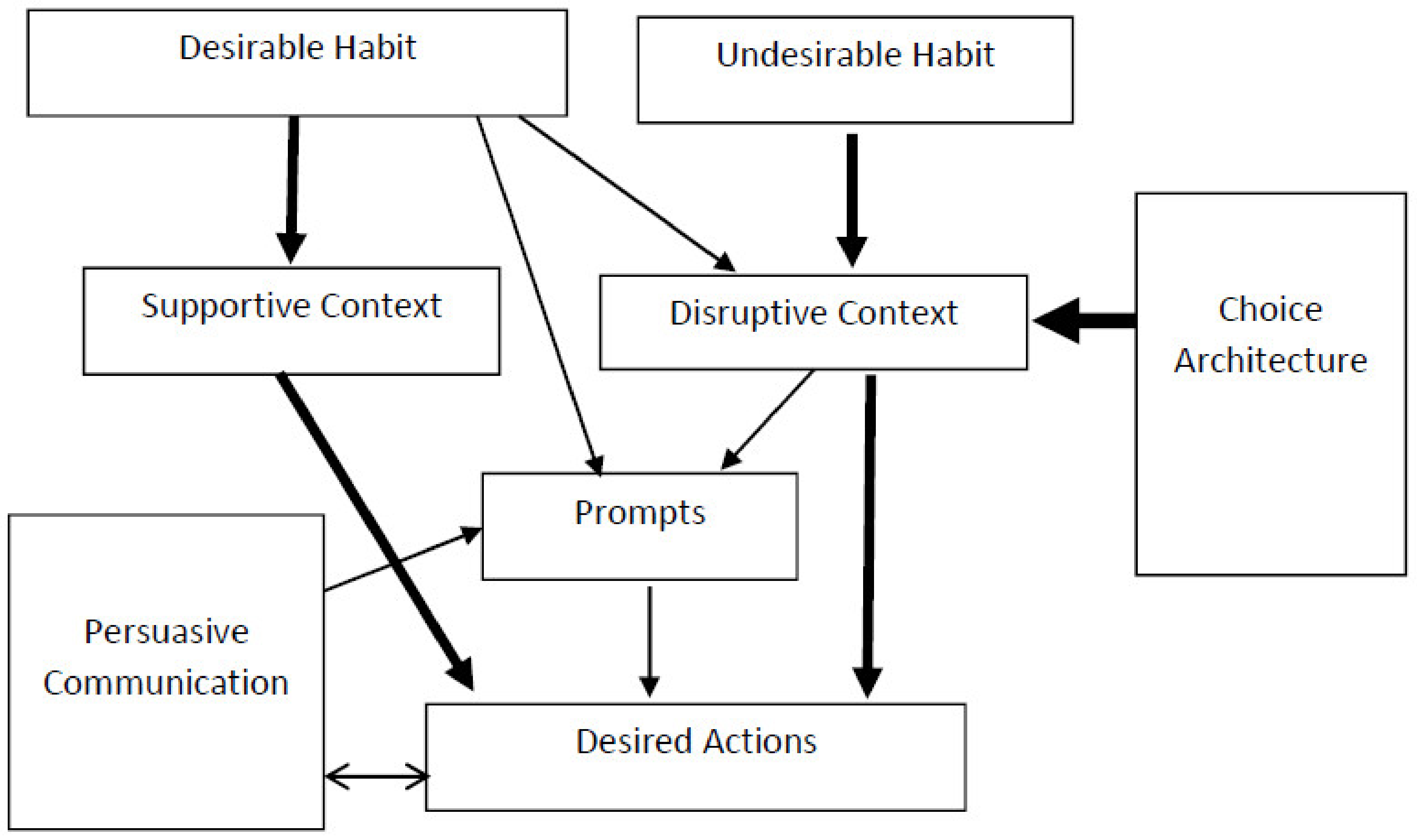

| Element | Features | Main Theories |

|---|---|---|

| Personal characteristics and social context | Personality Interest/motives Self-efficacy Values Social acceptability Previous experiences | Personality theory Social identity theory Value theory |

| Awareness | Knowledge of issue Knowledge of desirable actions | See persuasive communication |

| Acceptance | Belief actions will make a difference Trust in source of information Acceptance of responsibility Perceived social desirability or acceptability of action | Norms Trust |

| Attitude | Importance and accessibility of attitude | Attitude Theory |

| Intention | Intention | Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) |

| Ability | Perceived behavioural control Self-efficacy Resources—time, money and physical infrastructure | Choice architecture |

| Persuasive communication | Communication source credibility, trustworthiness and likeability Communication medium accessibility and usage Type of information included Nature of argument presented Ease of comprehension | Elaboration Likelihood Model Mindfulness theory Prospect theory (framing) Construal theory (fluency) |

| Physical setting and context organisation | Infrastructure provided Administrative procedures | Choice Architecture |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moscardo, G. Using Systems Thinking to Improve Tourism and Hospitality Research Quality and Relevance: A Critical Review and Conceptual Analysis. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 2, 153-172. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp2010009

Moscardo G. Using Systems Thinking to Improve Tourism and Hospitality Research Quality and Relevance: A Critical Review and Conceptual Analysis. Tourism and Hospitality. 2021; 2(1):153-172. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp2010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoscardo, Gianna. 2021. "Using Systems Thinking to Improve Tourism and Hospitality Research Quality and Relevance: A Critical Review and Conceptual Analysis" Tourism and Hospitality 2, no. 1: 153-172. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp2010009

APA StyleMoscardo, G. (2021). Using Systems Thinking to Improve Tourism and Hospitality Research Quality and Relevance: A Critical Review and Conceptual Analysis. Tourism and Hospitality, 2(1), 153-172. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp2010009