1. Introduction

Binturongs (

Arctictis binturong) are the largest members of the viverrid family, which comprises a group of cat-like mammals, such as genets and civets [

1]. Adapted to a solitary, arboreal lifestyle, the distribution of wild populations ranges from the forests of India to Southeast Asia [

1,

2,

3]. They are also a popular species within zoological institutions—a search on the Species360 Zoological Information Management System indicated a population of over 500 individuals under human care as of April 2025 [

4].

Diabetes mellitus is a well-studied condition in both humans and companion animals, characterized by persistent hyperglycemia and glucosuria, often seen with clinical signs such as polyuria, polydipsia and weight loss [

5,

6]. The disease mainly presents in 2 forms: Type 1 results from an absolute deficiency of insulin, associated with conditions such as the autoimmune destruction of pancreatic islet cells [

7]. Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is characterized by a loss of sensitivity of target cells to insulin. In this form, insulin secretion is insufficient to prevent hyperglycemia due to a relative deficiency [

7]. This condition has been documented predominantly in humans and in cats, where amyloidosis of the pancreatic Islets of Langerhans and associated β-cell failure are often reported in association with the disease [

7,

8]. Other manifestations of diabetes may also be associated with insulin resistance resulting from high concentrations of diabetogenic hormones such as cortisol, epinephrine, or progesterone [

7].

Reports of diabetes mellitus and available literature remain limited in zoological species, where reports of amyloid-associated T2D exist predominantly in non-human primates [

8]. Despite what we know of the condition in domestic felids and other species, the pathogenesis, mechanisms, and risk factors of amyloidosis-related diabetes have not yet been elucidated for the members of the family Viverridae. We conducted a search in February 2025, with the keywords “binturong”, “viverrid”, “diabetes mellitus” and “amyloidosis” entered into databases including Google Scholar, Elsevier, Bio-One and PubMed. While McFarland et al. recorded 2 cases of diabetes mellitus in a 2023 review of disease and mortality in 74 binturongs kept in the United States over a 33-year period [

3], we retrieved no published case reports of diabetes mellitus in binturongs, suggesting that the clinicopathological findings associated with this disease have not been reported in the species. Grey literature and non-peer-reviewed sources were not screened.

Despite our limited understanding of the diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus in zoological institutions, its implications on the long-term health and welfare of the animal cannot be understated. The use of hypoglycemic medications such as insulin can prove more challenging in zoo species, where dose ranges are poorly established and patient compliance may be low. Without treatment, common sequelae seen in domestic species include cataracts, peripheral neuropathies, and diabetic ketoacidosis [

6]. Developing our understanding of this disease in commonly kept zoo species will further subsequent efforts to develop methods for prevention and management.

In this report, we describe the clinical, biochemical and pathological findings of a geriatric individual which presented to the veterinary department at Mandai Wildlife Reserve. Given the popularity of binturongs in zoo collections, and the long-term implications of the disease, we hope that the findings here may direct further efforts to establish diagnostic and therapeutic methods in the species and identify risk factors and management methods in zoological institutions.

2. Materials and Methods/Case Description

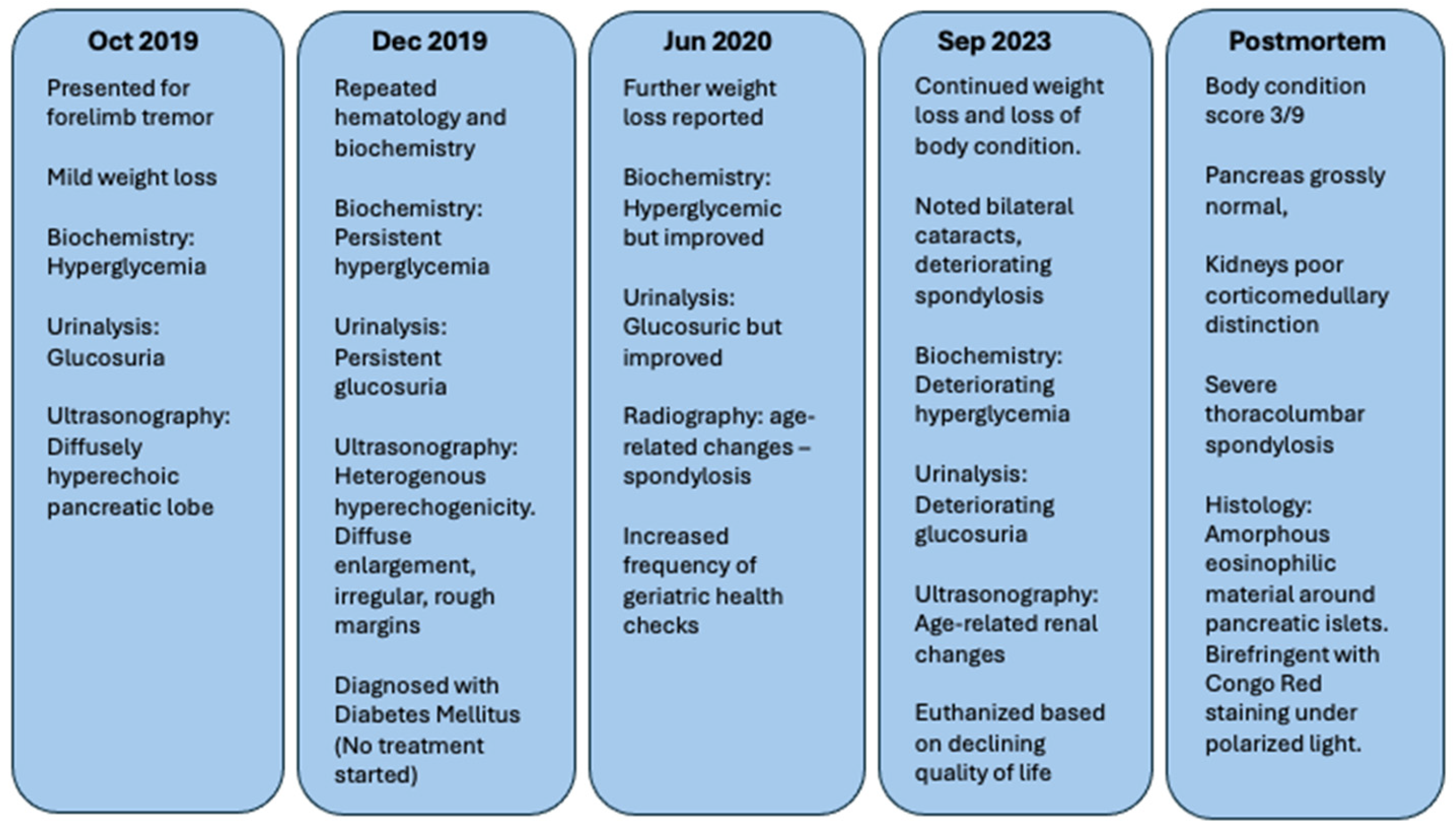

A 15.3 kg male binturong aged 16 years and 6 months presented on 10 October 2019 with tremors of the left foreleg, persisting over 4 days, as well as mild weight loss of 3.8% bodyweight over 2 weeks (

Figure 1). This patient was housed in an outdoor exhibit of approximately 400 m

2, with 24-h access to its indoor den, a building measuring approximately 3 m (l) × 3 m (w) × 2.5 m (h). The patient’s diet up until 2016 comprised mostly fruit but thereafter was adjusted to include a higher proportion of vegetables, better reflecting the species’ natural diet. Daily enrichment included the use of balls and toys in which food items were hidden, as well as numerous climbing structures within the exhibit.

Upon initial examination, a body condition score of 5/9 was assigned. Serum glucose was high (23.86 mmol/L; RI 2.93–18.94) (

Table 1), with concurrent glucosuria (approximately 500 mg/dL) (

Table 2). All hematology and biochemistry samples were run immediately following collection. All blood samples collected were drawn from either the patient’s cephalic or jugular vein under general anesthesia. To facilitate this, the patient was fasted for a minimum of 12 h, before sedation with 3 mg/kg of ketamine (Ketamine injection 100 mg/mL; Ceva Animal Health, Glenorie, NSW, Australia), 0.04 mg/kg of medetomidine (ilium Medetomidine hydrochloride 1 mg/mL; Troy Laboratories, Glendenning, NSW, Australia), and 0.15 mg/kg of butorphanol tartrate (Butomidor 10 mg/mL; Richter Pharma AG, Wels, Austria) administered intramuscularly. Testing was performed in-house using a ProCyte Dx Hematology Analyzer (IDEXX Laboratories, Inc. Westbrook, ME, USA) and a Catalyst One Chemistry Analyzer (IDEXX Laboratories, Inc. Westbrook, ME, USA), respectively. The Zoo Information Management System Global Reference Intervals (ZIMS, Species360, Bloomington, MN, USA) were used to obtain reference ranges for hematological and biochemistry values. As these reference ranges are updated monthly, reference ranges as accessed in April 2025 were utilized for the purpose of this report [

9]. All urine samples were collected by cystocentesis under general anesthesia and were analyzed immediately on collection. The gross appearance and urine specific gravity were noted for each sample. Cytology was performed using a wet mount preparation or stained with Diff-Quik for which findings were unremarkable. Samples were also analyzed in-house using urine test-strips (ABAXIS Global Diagnostics, Union City, CA, USA). We performed B-mode abdominal ultrasonography (MyLabEightVET Esaote S.p.A., Genoa, Italy), with the patient in dorsal recumbency. We used a convex-array ultrasound transducer (CA123, Esaote S.p.A, Genoa, Italy), noting the left lobe of the pancreas to be diffusely hyperechoic with smooth echotexture, and a chronic inflammatory process with associated saponification of the surrounding fat was suspected.

Bloodwork was repeated after 2 months (5 December 2019), in which hyperglycemia (27.71 mmol/L; RI 2.93–18.94) (

Table 1) and glucosuria (approximately >1000 mg/dL) (

Table 2) were found to be persistent. At this recheck, the binturong weighed 14.8 kg, and pancreatic changes suggestive of chronic fibrosis and suspected calcification within the pancreas were noted on ultrasonography. A generalized heterogenous hyperechogenicity and acoustic shadowing was reported in the pancreas, which appeared diffusely enlarged and irregular with rough margins (

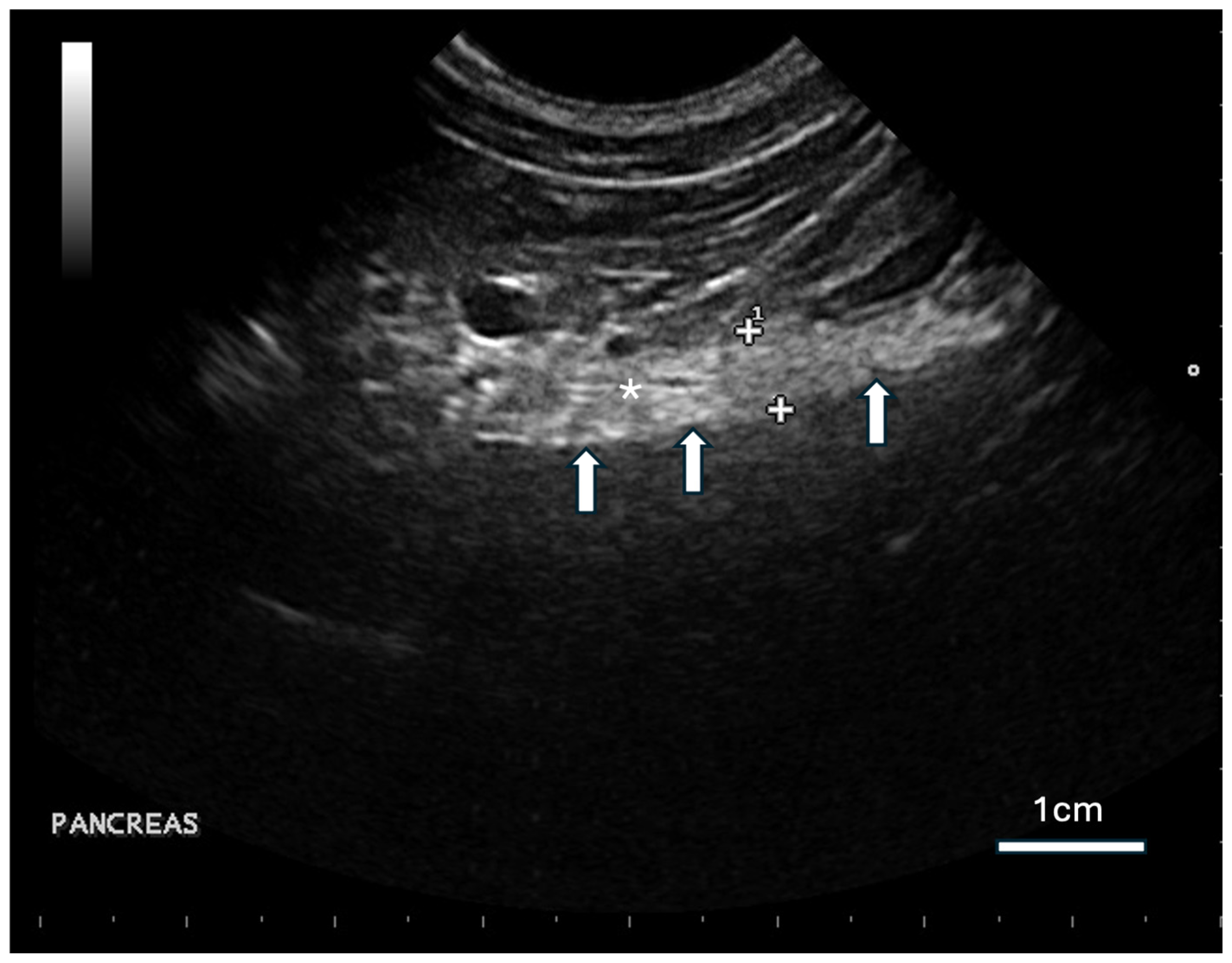

Figure 2). A primary diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was established. Due to the logistical challenges associated with the administration of antidiabetic agents in zoological species, management at this stage was limited to changes in husbandry and diet, with increased frequency of monitoring by keepers and veterinary staff for the progression of clinical signs.

The patient re-presented 6 months later (26 June 2020) for further weight loss with a recorded weight of 13.35 kg. Although significant improvement was noted with respect to the observed hyperglycemia (14.22 mmol/L; RI 2.93–18.94) (

Table 1) and glucosuria (approximately 5 mg/dL) (

Table 2), radiography noted age-related changes such as marked spondylosis of the thoracolumbar vertebrae. The patient was scheduled for biannual regular geriatric health checks to monitor the progression of this potentially painful and debilitating condition closely.

A gradual loss of weight and body condition was noted in the patient over the following 3 years. During a geriatric health check performed on 6 September 2023, the patient was found to weigh 13.1 kg and we noted the development of further changes including bilateral cataracts, and significant progression of spondylosis. We discovered age-related renal changes on an ultrasonographic examination and performed repeat blood tests, finding a marked increase in hyperglycemia (36.18 mmol/L; RR 2.68–15.65) (

Table 1) and glucosuria (approximately 500 mg/dL) (

Table 2).

Given the difficulties associated with patient handling and medication, long term management with antidiabetic medication was not considered to be a viable option, and continued husbandry-related changes were deemed unlikely to be successful, given the concurrent age-related comorbidities. Regular veterinary evaluations for quality of life were performed over the following 3 months, and the patient was euthanized in December 2023 on welfare grounds.

Ethical approval was not required for this case report, all diagnostic testing and treatments were performed as part of routine clinical and therapeutic management of the patient by the attending veterinarians. No experimentation outside of routine veterinary care was performed.

3. Postmortem Findings

A postmortem was performed immediately following euthanasia. The animal was 20 years and 8 months old at the time of death, with a body weight of 12.4 kg and an assigned body condition score of 3/9.

Gross examination found the pancreas and surrounding tissue to be normal in appearance. Other findings which were noted to be incidental included a focal, well-demarcated, 1.0 × 0.5 cm area of thickened, white fibrous tissue on the pectoral muscle, with similar multifocal lesions observed on the fascia at the sternal insertion of the pectoralis major. The heart appeared enlarged, with decreased myocardial tone and a rounded apex. A well-circumscribed, 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 cm3 cystic structure was identified cranial to the left thyroid gland, with no grossly obvious connection between the 2 structures. The kidneys bilaterally exhibited poor corticomedullary distinction. Severe spondylosis was present at the thoracolumbar vertebral level.

Samples were collected and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histological examination. Formalin-fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin and cut into 3–4 um sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

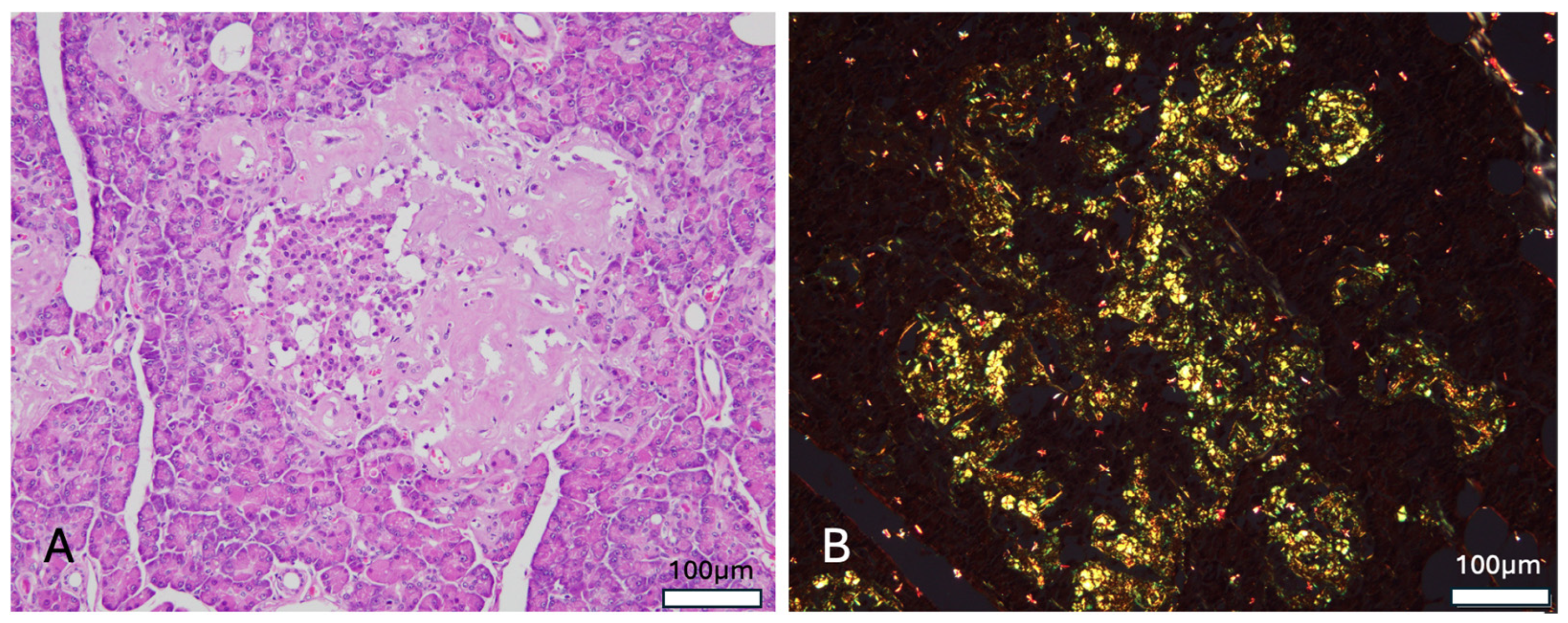

Histological examination of the pancreas revealed deposition of an amorphous eosinophilic material around pancreatic endocrine islets, with some lesions expanding into the adjacent exocrine acinar tissue (

Figure 3A). Approximately 70% of islets seen within the cut section were affected. Congo red staining demonstrated apple-green birefringence under polarized light, consistent with amyloid deposition (

Figure 3B). Immunohistochemical analysis for islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) was not performed due to cost and logistical limitations. In the kidney, focal thickening of the glomerular basement membrane was observed in some glomeruli, along with mild to moderate focal adhesion at the glomerulo-tubular junction, where collagen deposition was confirmed via Masson’s trichrome stain. Additionally, the adrenal parenchyma was found to contain two small osteolipomas composed of mature adipose tissue and bone elements. In the skeletal muscle, 2 small foci of Sarcocystis infection were identified within the myocytes, each containing numerous large bradyzoites.

4. Discussion

Primary findings on postmortem, particularly the presence of pancreatic islet amyloidosis were most consistent with that of T2D as observed in humans, and other species such as the cat [

7,

10]. Islet amyloid polypeptides (IAPP), a neuroendocrine hormone involved in the regulation of glucose homeostasis, is normally co-produced with insulin in response to glucose [

10]. IAPP sequences are susceptible to sudden post-translational modifications that increase the risk of misfolding and thus amyloid formation only in certain species, including humans, cats and non-human primates [

10]. In cases of T2D, the resulting amyloidosis within the Islets of Langerhans of the pancreas further leads to β -cell dysfunction and cytotoxicity, a hallmark feature of this form of the disease [

10]. Although pancreatic amyloidosis has not yet been documented in the binturong, our findings in conjunction with the classification of Viverridae within the suborder Feliformia suggest that the feline model of T2D may be a useful tool in understanding the progression of diabetes in the species.

Several limitations to this paper include the single-case nature of this report. Further observations and studies regarding similar presentations within the species will strengthen our understanding of the presentation and pathogenesis of this disease process in binturongs. Furthermore, the lack of immunohistochemical analysis to confirm the nature of the amyloid deposits seen is noteworthy. While the presence of amyloid deposition in this case can be confirmed by histology and Congo Red staining, the use of immunohistochemistry could further strengthen this report by differentiating IAPP from other amyloid types such as serum amyloid A, or amyloid light-chain. As this test has not yet been validated in the species, an assay with cross-reactivity to the domestic cat would likely serve as the best available proxy. Nevertheless, the morphological features and restriction of deposition to the pancreatic islets in this patient are most consistent with IAPP deposition, as reported in cats and humans.

This case report emphasizes the challenges of diagnosing diabetes mellitus in zoological species. There are no universally accepted criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes in animals [

5], and diagnosis, as in this case, is often presumptive through the observation of clinical signs as well as hyperglycemia and glucosuria [

6,

7]. In animals, parameters above which serum glucose levels are considered diagnostic are not well established, and in some species, may be further confounded by factors such as stress [

6]. Similarly, the interpretation of glucosuria must be done with care, as it too may manifest in other conditions such as renal disease [

6]. Furthermore, the renal threshold for glucose has not been established in binturongs.

Although the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was ultimately supported by clinicopathological tests and postmortem histological evidence of pancreatic islet amyloidosis, its clinical significance and manifestation in the patient appear atypical. Despite the patient’s initial presentation due to the observation of a forelimb tremor, no further mention of this was noted in subsequent records, implying possible spontaneous resolution. While diabetic neuropathies have been reported in feline cases of diabetes mellitus, reports most commonly involve signs such as weakness, a plantigrade stance, and depressed reflexes [

6]. It is thus unclear if T2D served as the underlying etiology for the patient’s initial tremor, and further studies are needed to explore such presentations in binturongs.

In addition, clinical presentation of this individual was unusual in its lack of overt polydipsia and polyuria, which are often reported in domestic species once the renal threshold for glucose has been surpassed [

6]. However, factors such as the impracticability of measuring fluid intake and urination in zoological species should also be considered. The non-specific findings of weight loss and loss of body condition were the main clinical signs noted in the years following diagnosis. The relatively mild and gradual progression seen, and the patient’s prolonged survival time despite the lack of pharmaceutical intervention is noteworthy. While weight loss is commonly observed in diabetes mellitus, the onset of age and processes such as spondylosis and bilateral cataracts may also have played a role here. Furthermore, the etiology of the bilateral cataracts, a known sequela to diabetes mellitus in other species but notably rare in cats [

6], was not elucidated in this binturong, and so may have been diabetogenic. The patient’s geriatric age thus serves as a confounding factor in establishing the clinical significance of the disease in this case.

Diabetes mellitus in other species has been noted to occur in association with conditions such as chronic kidney disease and hepatic lipidosis [

6]. Although antemortem findings in this patient such as a persistent proteinuria suggested a degree of glomerular dysfunction, and gross and histopathological changes were detected in the patient’s kidneys on postmortem examination, no evidence of azotemia or elevated liver enzymes were noted, further highlighting the difficulties in associating these findings with organ function and disease in zoological species.

The ultrasonographic abnormalities noted in this patient were more suggestive of chronic pancreatic changes secondary to previous episodes of pancreatitis such as fibrosis or calcification, rather than amyloid deposition. This was further supported by a mild increase in serum lipase, although serum amylase remained within reference ranges, and gross changes to the pancreatic tissue were not noted on postmortem examination. In domestic animals, the use of serum lipase and amylase as stand-alone tests should be interpreted with caution due to their limited sensitivity and specificity [

11], and elevations in lipase have been noted in conditions such as renal or gastrointestinal disease [

12]. The authors suggest that the collection of pancreatic biopsies for histological examination following diagnostic imaging may have facilitated antemortem diagnosis and should be a consideration for future cases.

The use of exogenous insulin and other hypoglycemic medications was not deemed suitable in this patient due to several limiting factors. Commonly used treatments in domestic species include parenteral glargine (Lantus) in cats as well as U-40 pork lente in the domestic dog [

13]. Such treatments are complicated by the need for frequent and primarily parenteral administration, for which achieving patient compliance in zoological species often proves difficult. Oral hypoglycemic options exist which may improve patient compliance, such as glipizide and metformin, the latter of which was successfully trialed in callitrichids in a 2017 study [

14,

15]. However, the 2018 American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) guidelines of diabetes management in domestic species advises against their long-term use and suggests their use as a temporary adjunct in combination with methods such as dietary adjustments [

13]. Furthermore, any such treatment carries risks such as hypoglycemia and necessitates constant monitoring and adjustments to dosage over the span of the animals’ treatment, due to the continuously changing state of the animal and its response to therapy [

13]. Coupled with the lack of established protocols for insulin dosage and use in non-domestic species, these methods carry significant risk. In the absence of overt clinical signs or welfare impairment, the costs and benefits of instituting treatment should be weighed carefully in zoological species on a case-by-case basis. Further research is needed to establish safe protocols and methods of administration.

Considering these challenges, a more practical approach in zoological institutions likely lies in mitigating predisposing risk factors. Such factors in both humans and animals are well established and include genetics, obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, and old age [

7]. As such, steps taken may include the careful calculation of an individual’s caloric requirements, matching captive and wild nutrient composition, frequent weight measurements and body condition scoring, and increasing opportunities for physical exercise and enrichment [

13]. An overall reduction in carbohydrate content in favor of high protein food items would also assist in achieving weight loss for obese individuals while maintaining lean muscle mass and mitigating diabetes-associated weight loss [

13].