1. Introduction

In recent decades, interest in nature-based tourism has increased, encompassing forms of travel centered on experiences in nature, green spaces, and environmentally responsible activities [

1,

2]. Botanical gardens, which serve multiple roles—scientific, educational, conservation, and recreational—are seen as valuable resources that can improve the tourism experience and satisfy the growing demand for sustainable and eco-friendly content [

3,

4]. Despite the rise in research on nature-based tourism and visits to urban green spaces, the specific topic of tourist valorization of botanical gardens remains underexplored scientifically. The existing literature has mostly focused on the ecological and educational roles of botanical gardens as well as their importance in preserving biodiversity. At the same time, the analysis of their tourist potential and visitor experience has remained fragmented and rarely supported by empirical evidence. In particular, there is a lack of studies that compare and rank botanical gardens based on their attractiveness and valorization possibilities through defined criteria.

Here, this gap is addressed by providing a methodological framework that allows for the systematic evaluation of botanical gardens in the function of tourism. The goal is to develop a structured, methodological approach to evaluating botanical gardens based on predefined criteria, to enhance tourist appeal. This objective was established to identify the garden with the highest tourist potential, attractiveness, and capacity for tourist valorization. To achieve this, the focus of this study was on evaluating botanical gardens in Split–Dalmatia County. This county was chosen because it has the most botanical gardens among all counties in Croatia. Its unique feature is that it primarily offers a tourist experience centered on the sun and sea. To complement this, it is necessary to offer tourists a diverse range of content. Botanical gardens complement existing tourist offerings and can also serve to introduce tourists to the local plant life specific to this region, enriching the attractions necessary for the sustainable and balanced development of a tourist destination. Botanical gardens are visual centers that combine plant study, preservation, educational functions, aesthetic appeal, and spaces for enjoyment and relaxation. Their importance is growing due to climate change and the extinction of plant species, as they act as repositories of knowledge and means of preserving plant diversity for future generations. All of these aspects should be used to boost tourism and attract visitors. For this reason, all botanical gardens in the county were included in the research and examined to determine how they could be integrated into the tourism offer. Based on this, the central research question was set: How can botanical gardens be transformed to enhance the tourist experience and become genuine attractions within sustainable tourism strategies?

The implementation of this research was carried out using the multi-criteria decision-making method (MCDM). The basis of these methods is that, according to the defined criteria, alternatives are assessed through a rank order. Since the selected criteria are qualitative in nature, the evaluation is based on a linguistic value scale, with fuzzy methods SiWeC and TOPSIS. This transition involves moving from descriptive to quantitative, comparative evaluation, which includes a clear ranking function.

Based on all of the above, the following research questions are set:

What criteria should be used to evaluate botanical gardens?

Which botanical garden presents the best research results, and why?

What insights can be drawn from this research to help enhance the tourist experience?

To our knowledge, no empirical research has yet been conducted to compare and rank botanical gardens based on specific criteria. This makes the research innovative, fills a scientific gap, and provides practical guidelines for decision-makers, garden management, and the tourism sector in shaping development and promotional strategies.

2. Literature Review

A review of the literature reveals a steady and increasing interest among tourists in natural, “green,” and environmentally responsible experiences—from walks in parks to visits to protected areas and urban green oases. Nature-based tourism is growing, and destinations that include additional green infrastructure, such as parks, gardens, and interpretive trails, stand out and appeal more to environmentally conscious travelers [

1,

2,

5,

6]. Urban parks and green spaces are popular due to their accessibility, landscape beauty, safety, cleanliness, and diverse recreational options. Visitors respond positively to variety, tranquility, contact with nature, and well-maintained infrastructure [

7,

8]. Online reviews confirm that accessibility and perceived attractiveness, including aesthetic qualities and content offerings, are key factors in choosing to visit [

9].

Although “garden tourism” has existed for decades, scientific research on visitors’ motives and the touristic role of gardens has long been limited. Connell [

10] identified a wide range of visitor motives—from recreation and aesthetic pleasure to inspiration for personal gardens—illustrating how gardens occupy a specific niche in leisure tourism. Later research has deepened the understanding of motives and perceptions. Setiadi [

11] emphasizes the ethnobotanical potential of the Bali Botanic Garden, while Goh and Mahmud [

12] show that in Kuala Lumpur’s Perdana Garden, tourism and recreational functions often overlap but also conflict due to differing visitor expectations. Similarly, Cudjoe and Gbedemah [

13] in Ghana emphasize the importance of recreation and new features, such as a canopy walkway, as primary motivations. Meanwhile, Rahmawati et al. [

14] examine visitor perceptions and satisfaction at Sukorambi Garden to guide development strategies.

Botanical gardens can be defined as institutions with documented collections of living plants, intended for scientific research, conservation, exhibition, and education. Empirical studies indicate that visitors see botanical gardens as places for rest, recreation, and observing nature, especially valuing their aesthetic appeal, tranquility, and diverse landscapes [

3]. Therefore, botanical gardens function not only as passive spaces but also as active sites for interpreting natural heritage. Williams et al. [

15] confirm that visiting botanical gardens has a positive impact on knowledge and attitudes about biodiversity, as well as on people’s health and well-being, reaffirming their educational and social importance.

In addition to cultural and educational value, botanical gardens also have economic value. Jayaratne and Gunawardene [

16] assessed the recreational value of Hakgala Garden in Sri Lanka using the travel cost method, while Karaşah and Var [

17] highlight the recreational functions of Nezahat Gökyiğit Garden in Istanbul. Safarinanugraha et al. [

18] in Bogor Garden, Indonesia, showed that quality environmental management has a strong impact on visitor satisfaction. Salvarcı and Aylan [

19] confirmed this by analyzing reviews, which revealed that peace, beauty, and education are key dimensions of the visitor experience.

To effectively promote botanical gardens, it is important to implement digital marketing strategies to raise awareness of their existence in the digital era. Zhang et al. [

20] emphasize that, in addition to informing visitors about the existence of these gardens, the gardens themselves promote sustainable and ecologically responsible tourism. Catahan et al. [

21] share a similar opinion, suggesting that gardens should be used to promote their values by offering additional tourist services within them. Additionally, using botanical gardens is crucial for promoting educational content and inspiring future generations to appreciate the value of these gardens [

22].

Seasonality remains one of the biggest challenges in modern tourism, especially in Mediterranean destinations. Botanical gardens, with their programs and attractions, can draw visitors year-round, helping to stabilize tourist demand. Gardens and related green attractions extend the tourist season, while an analysis of the botanical garden industry confirms that they offer programs and events throughout the year [

21]. In this way, they serve as a strategic tool for reducing seasonality.

One of the additional benefits of tourism valorization is its role in raising environmental awareness and promoting sustainable development. Catahan et al. [

20] point out that visitors to gardens are not only seeking recreation but also an opportunity to enhance their personal experience as well as social and educational value. The most recent research conducted by Middel et al. [

23] on a Lowveld Garden in South Africa confirms the multidimensional benefits of visits, which can be categorized into five areas: socio-cultural benefits, relaxation and stress relief, mental well-being, recreation, and exposure to biodiversity. In this way, botanical gardens serve as a platform for developing sustainable tourism that combines visitor satisfaction with the preservation of natural heritage and social responsibility. Furthermore, they contribute to achieving the global sustainable development goals, especially those related to well-being, health, and nature conservation (SDG3 and SDG15), thereby aligning with the international framework of sustainable tourism [

24].

3. Methodology

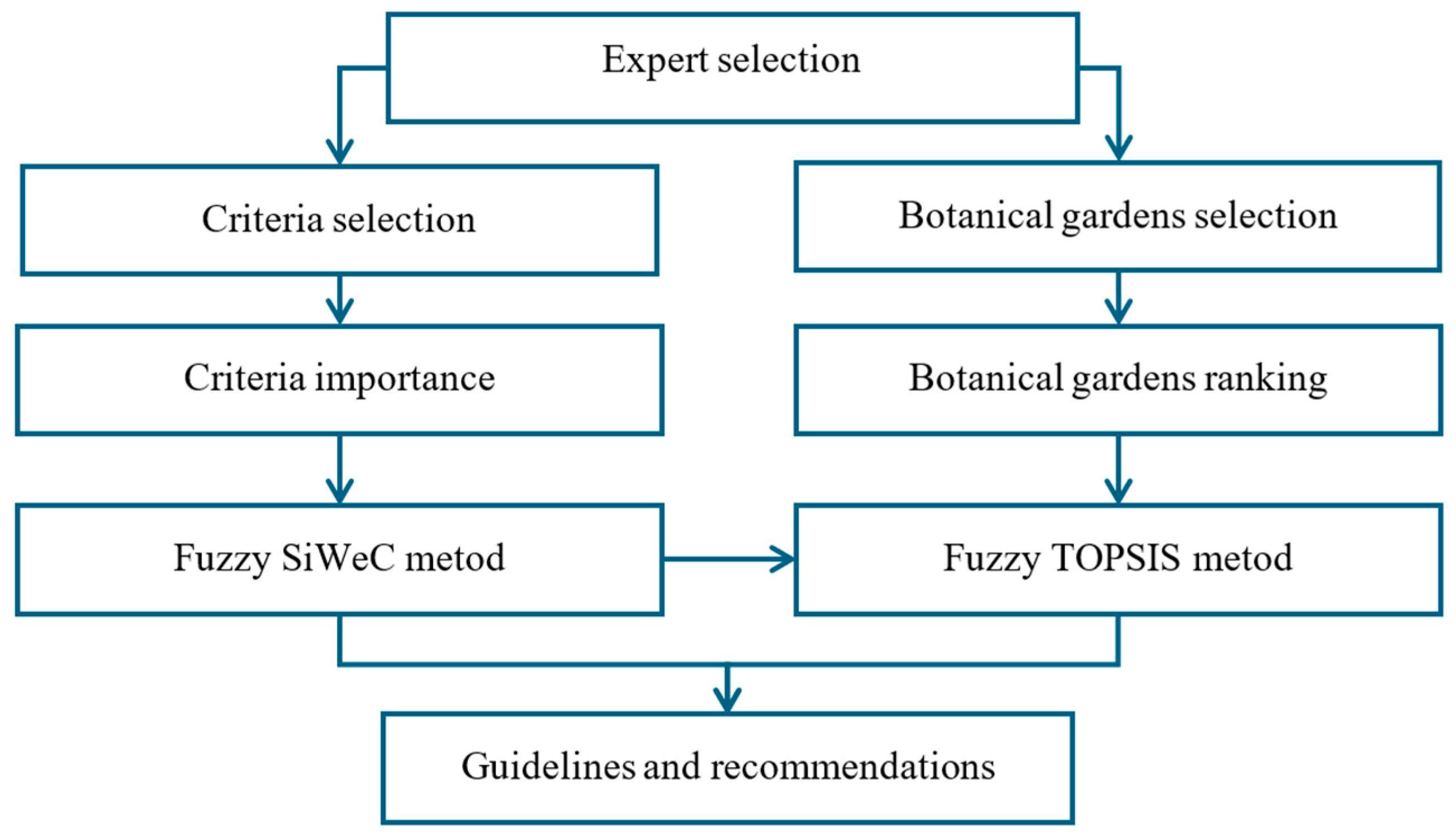

Since it is not possible to include all botanical gardens, this research was conducted using Croatia as an example. The reason for this is that Croatia generates a significant portion of its income through tourism and is visited by numerous tourists. To enhance this offer, botanical gardens were used as an additional form of tourism that is not common. Botanical gardens exist, but they are not typically promoted as tourist attractions. Therefore, primary research assesses the botanical gardens in Split–Dalmatia County in terms of their tourism potential. This county was chosen because it has the largest number of botanical gardens in Croatia; additionally, it features various types of gardens, including school, island, and urban gardens. The selection of these gardens, due to their specific features, is representative for achieving this research goal. Based on this, a methodology was developed for this research, which can serve as an example for similar studies in other countries. The research involves the following phases, shown in

Figure 1.

The first phase of this research involves selecting experts. Eight local tourism experts were selected for this research. The selected experts are based in the area and are knowledgeable about the locations of the specific botanical gardens. Additionally, they were responsible for deciding which gardens should be included in this research.

3.1. Descriptions of Botanical Gardens in Split–Dalmatia County

The second phase of this research involves consulting experts about the selection of criteria and alternatives. A total of six botanical gardens were chosen, and nine criteria were used to evaluate them. In this paper, six botanical gardens located in the Split–Dalmatia County are examined: Zaostrog Botanical Garden (BG1), Kotišina Botanical Garden (BG2), Hvar Botanical Garden (Dol) (BG3), Mary’s Garden (Brač) (BG4), Split Botanical Garden (BG5), and Ostrog Primary School Botanical Garden (BG6). The choice of these six gardens within Split–Dalmatia County was based on several reasons. First, Croatia is a highly tourism-focused country, where tourism contributes significantly to the GDP, making research on diversifying and sustaining the tourist offer especially important. Split–Dalmatia County is one of Croatia’s top tourist regions, where the dominant “sun and sea” model is increasingly facing challenges related to seasonality and the need to incorporate nature- and sustainability-based content into the offering. These gardens represent a comprehensive sample of the region’s botanical gardens, varying in size, location, function, and level of development, allowing for meaningful comparison. The Zaostrog and Kotišina Botanical Gardens are near mountains and natural parks, playing important educational and conservation roles. The Hvar Botanical Garden (Dol) and Mary’s Garden (Brač) are island gardens that can enhance the tourist experience of their respective islands. The Split Botanical Garden, situated in an urban area, has the potential to serve as a “green rest area” in a city with high tourist traffic. Meanwhile, Ostrog Primary School Botanical Garden offers a unique blend of educational and tourism opportunities. By selecting these six gardens, a representative sample was created, allowing for the testing of the evaluation framework and the comparison of different types of botanical gardens within one of Croatia’s most important tourist regions.

3.2. Research Criteria and Evaluation of Criteria and Alternatives

The defined criteria were developed through a review of the literature and collaboration with experts. First, based on previous research, a list of potential criteria for this study was created. Then, in collaboration with experts, the most important criteria for this research were selected.

Table 1 shows the criteria used in previous studies that will be applied in evaluating botanical gardens for tourism purposes.

After the selection phase, which involves evaluating criteria and botanical gardens, the third phase follows. This phase assesses the importance of the criteria and examines how botanical gardens meet them, as evaluated by experts. Since the criteria are observed through the qualitative dimension, the assessment of the criteria and botanical gardens will be conducted using linguistic assessments. These evaluations aim to make the research more relatable to human thinking, as it is easier to provide approximate assessments rather than exact numerical ones. It is difficult to determine the precise value that a criterion or botanical garden must have to receive a rating of 4 or 5; however, it is relatively easy to judge whether something is good or very good. Therefore, in this research, linguistic values will be used with nine levels of disagreement and agreement with the set research criteria (

Table 2).

3.3. MCDMs Used in the Research

To use these ratings more effectively, a fuzzy approach was adopted. This method enables decision-making when the decision-maker (DM) has incomplete information, allowing decisions to be made based on limited data, particularly when linguistic values are used as ratings [

33]. Therefore, before starting the fourth phase of this research, it is essential to define a membership function [

34]. This function determines how the existing linguistic values will be converted into fuzzy numbers [

35]. In this research, triangular fuzzy numbers are used, and the membership function is defined accordingly (

Table 2). The fourth phase involves applying the steps of the fuzzy SiWeC and TOPSIS methods. The fuzzy SiWeC method will be used to evaluate the importance of the criteria. To identify which botanical garden has the highest tourism potential, these gardens will be ranked using the fuzzy TOPSIS method. The steps for these methods will be explained in the following sections.

The fuzzy SiWeC method was selected because it simplifies the process of determining criterion weights. In this method, it is necessary to evaluate the importance of each criterion, and then, based on this evaluation, the final weight is assigned [

36]. The foundation of this method relies on expert ratings expressed as linguistic values. To obtain these ratings, experts do not need to compare or rank the criteria by importance; it is sufficient for them to indicate the importance of a specific criterion based on their opinion [

37]. Additionally, this method allows for different levels of importance to be assigned to expert ratings. Experts with relatively similar ratings will have less influence, while those with more divergent ratings will have greater influence. This method encourages a broader spread of ratings among experts and was first implemented by Puška et al. [

38], who outlined the method’s steps as:

Step 1. Criteria evaluation.

Step 2. Linguistic values transformation.

Step 3. Fuzzy numbers normalization.

where

is the maximum value of the fuzzy number.

Step 4. Standard deviation calculation ().

Step 5. Normalized values weighting.

Step 6. Aggregate weights calculation.

Step 7. Criteria weights determination.

The TOPSIS method is one of the most widely used MCDM in practice, and no justification for its use is necessary [

39]. Therefore, this method was chosen to rank botanical gardens. The principles of this method were introduced by Hwang & Yoon [

40]. Based on this approach, other variations of this method have been developed [

41]. The steps of this method for this research are:

Step 1. Alternative evaluation.

Step 2. Linguistic values transformation.

Step 3. Fuzzy numbers normalization.

where

is the maximum value of the fuzzy number for each criterion.

Step 4. Weighting process.

Step 5. Ideal and anti-ideal alternatives calculation.

Step 6. Calculation of deviations from ideal and anti-ideal alternatives.

Step 7. Relative closeness and ranking.

4. Results

When conducting this research, the importance of the criteria weights is determined first because these weights are crucial for ranking botanical gardens. The results from the fuzzy SiWeC method are linked with those from the fuzzy TOPSIS method. To determine the importance of the criteria weights, an expert assessment is initially conducted. In this step, experts provide assessments using linguistic values (

Table 3).

To apply the fuzzy SiWeC method, it is necessary to transform linguistic values into fuzzy numbers. For example, the value “Absolutely good” is transformed into a fuzzy number (9, 10, 10). By using the specified membership function, all linguistic values of expert ratings are transformed into fuzzy numbers. After the fuzzy numbers are generated, normalization is carried out. Since the ratings include the highest rating, “Absolutely good,” with a maximum fuzzy number value of 10, all these numbers are divided by this maximum. For instance, the calculation for Expert 1 and criterion C1 is as follows:

In fact, since the divisor is 10, the decimal point of the fuzzy numbers is only moved by one place, so the normalized matrix remains the same as the initial matrix, only scaled down by a factor of 10 (

Table 4). The next step is to calculate the standard deviation for all values of the normalized fuzzy numbers for each expert (

Table 4). Based on these standard deviation values, it is evident that the ratings of Expert 4 will have the greatest influence on the final criteria weights, while those of Expert 1 will have the least influence.

Next, the weighting step follows, where the normalized scores are multiplied by the standard deviation value. In the same example, this is done as follows:

The final steps of the fuzzy SiWeC method involve calculating the sum of the weights and determining the weights of the criteria. The sum of the weights is found by adding all the weighted values for each criterion, while the weight of each criterion is obtained by dividing the sum of its weighted values by the total sum of all weighted values. For example, the calculation for criterion C1 is as follows:

Based on the expert ratings and the steps of the fuzzy SiWeC method, the most important criterion is C4—Visitor content, followed by C5—Water features in the garden. The least important is C7—Cultural & historical proximity (

Table 5). These ratings highlight the importance of offering visitors diverse content, a key factor in encouraging them to visit botanical gardens. Additionally, incorporating a variety of water features can enhance visitor satisfaction during their visit.

After assigning the weights to the criteria, the next step is to assess the botanical gardens based on these criteria. The fuzzy TOPSIS method will be used to rank the botanical gardens. Since this method has been used in numerous studies, its detailed steps will not be explained here. The initial step involves experts evaluating the botanical gardens (

Table 6). In this stage, an assessment is also made using linguistic values, which helps determine how well each botanical garden meets the set research criteria.

The next step is similar to the fuzzy SiWeC method, which involves transforming linguistic values using defined membership functions. Then, a summary decision matrix is created by averaging the results from all experts. Afterward, this decision matrix is normalized by identifying the highest value for each criterion and dividing the remaining values by this maximum. For example, for criterion C1 and Zaostrog Botanical Garden (BG1), this process is calculated as follows:

After the normalized decision matrix is created, it is weighted using appropriate weights. In the same example, this is done as follows:

Then, it is necessary to establish an ideal and an anti-ideal alternative for all criteria. The ideal alternative represents the highest value among individual alternatives for each criterion, while the anti-ideal alternative is the lowest value. Next, the deviations from these alternatives are calculated to create a ranking of botanical gardens (

Table 7). The results, based on expert assessments and the steps of the fuzzy TOPSIS method, show that the Botanical Garden of the Ostrog Elementary School (BG6) shows the best outcomes, followed by the Botanical Garden of Split (BG5). The least favorable results are seen with Marijin Vrt (Brač) (BG4). These results likely stem from how well each botanical garden meets the set criteria. Analyzing their evaluations, it becomes clear that the Ostrog Elementary School Botanical Garden (BG6) demonstrates the strongest indicators in nearly all criteria, which explains why it was ranked as the top botanical garden for tourism valorization.

The evaluation results can serve as a guide for garden management, tourist boards, and local institutions when making decisions about investments, promotion, and strategic development. A clear ranking and identification of the most attractive garden allows for more efficient resource allocation. The developed framework can serve as a pilot model for implementation in other countries, regions, or territories, and can be further enhanced with additional criteria (e.g., digital interaction, spatial analysis, economic viability). This creates opportunities for standardizing the evaluation of the tourism quality of botanical gardens.

5. Discussion

Tourism as an economic activity is becoming increasingly important because its impact significantly influences a country’s development [

42]. Therefore, investments are made in developing tourism, and efforts are focused on enhancing this industry. The foundation for improvement lies with tourists, who seek diverse experiences to attract them to specific locations. It is essential to influence their satisfaction [

43], which is achieved through tailored tourist offerings [

44]. Croatia’s tourism primarily centers on sun and sea attractions. However, many countries offer similar experiences, so it is necessary to diversify offerings further to attract more tourists.

This research explores the potential of integrating botanical gardens into tourism offerings. While many studies, starting with Connell [

10], have highlighted the tourism potential of botanical gardens, they represent just one of the many functions these gardens serve. Key functions include ecological conservation [

1], recreation [

7], aesthetic benefits [

9], and the protection of endemic plant species, among others.

The importance of botanical gardens in the tourist offer is evident in the role they play in tourism recovery following the COVID-19 pandemic, where the emphasis should shift from mass tourism to offering a diverse range of attractions for tourists. Additionally, tourists themselves are seeking new forms of tourist offerings and are becoming increasingly receptive to ecological tourism [

45]. This would balance tourist visits, thereby achieving sustainability in tourism [

46]. In this way, the use of botanical gardens can also serve as a countermeasure to overtourism, all while protecting the natural resources that a particular region relies on for tourism [

47]. To achieve this, it is necessary to conduct digital promotion of this form of tourism, as the selection of tourist locations is primarily done through internet searches [

48]. Therefore, it is necessary to promote botanical gardens and their offer in order to attract tourists.

The choice of Split–Dalmatia County as a case study for the role of botanical gardens in tourism was based on its numerous botanical gardens, particularly around the city of Split. To gather expert insights, eight tourism professionals, all based in or near Split, were selected. They evaluated six botanical gardens within the county, using nine specific criteria to comprehensively assess each site.

The experts’ role was first to determine the importance of each criterion and then to evaluate how botanical gardens contribute to tourism. The selection of assessment methods was based on the types of criteria used in this research, which are qualitative [

49]. When evaluating these criteria, the challenge lies in providing accurate assessments, as assigning precise numerical scores to certain criteria can be difficult [

50]. To address this, linguistic values were used to evaluate the criteria and botanical gardens. Additionally, to make these assessments applicable in practice, a fuzzy approach was adopted. This method simplifies decision-making in situations where complete information is unavailable, and linguistic values are used [

51].

In this research, the fuzzy SiWeC method was used to determine the importance of the criteria, and the fuzzy TOPSIS method was used to assess how the selected botanical gardens meet these criteria. The results of the fuzzy SiWeC method indicated that the most important criteria for implementing tourism activities in botanical gardens are the content for visitors and water features in the garden. Therefore, it is necessary to have diverse content in botanical gardens, including water features whenever possible. This is because a monotonous and content-lacking botanical garden will not be engaging for visitors, and as a result, it cannot serve as an effective tourist attraction.

The results of the fuzzy TOPSIS method indicated that the Ostrog Elementary School Botanical Garden received the highest scores. This garden is unique because it is a protected monument of park culture, making it the only one of its kind in Croatia. It is divided into several main sections, including areas for sports and recreation. Interestingly, the garden was established through an initiative by teachers and students aimed at enhancing the local environment. Additionally, new plant species are frequently introduced alongside existing ones, resulting in about 1000 different plant varieties. Due to these features, the garden was designated as the best example for promoting tourism activities. Other botanical gardens could look to this one as a model for improving their offerings and attracting a broader audience, including tourists.

This research shows that all observed botanical gardens can enhance the tourist experience; therefore, investing more in planning new botanical gardens and developing existing ones is necessary. These gardens should play a greater role in tourism and be included to extend the tourist season. Currently, the tourist offerings in Croatia and other countries primarily rely on the sea and sun, while other types and forms of tourism are often overlooked. Promoting various types of tourism and presenting diverse attractions that can be incorporated into the tourist offer is essential. Additionally, botanical gardens offer opportunities to develop educational programs and organize excursions for students. As their importance grows, botanical gardens can play a crucial role in promoting the preservation of specific plant life in certain areas. Since the best results were achieved by school botanical gardens, establishing partnerships with local communities and schools through tourism strategies is key to further developing these gardens. Moreover, findings suggest that involving other interest groups in destination development is beneficial. This can be achieved by developing partnerships and coordinating interdepartmental efforts, reducing the burden on individual resources in tourism.

6. Conclusions

This research aimed to identify the botanical garden in Split–Dalmatia County with the greatest potential for tourism activities. For this purpose, eight experts participated in the study, evaluating six botanical gardens based on nine criteria. Using the fuzzy SiWeC and TOPSIS methods, the results showed that the Ostrog Elementary School Botanical Garden was the top choice, with visitor facilities and water features being the most important criteria.

The significance of this paper lies in its status as the first scientific effort to systematically evaluate botanical gardens based on clearly defined criteria such as attractiveness, tourist potential, and valorization possibilities. Prior research has primarily concentrated on their ecological and educational roles or on describing individual gardens. At the same time, comparative and methodological analyses of their attractiveness in relation to tourism have been largely overlooked. This paper addresses that gap by establishing a methodological framework adaptable to various geographical contexts, regardless of a garden’s location or specific features.

The scientific contribution is demonstrated through the integration of theoretical knowledge from tourism, nature conservation, and the management of cultural and natural heritage, along with a practical evaluation tool that enables the comparison and ranking of botanical gardens. The practical value of the research is also highlighted: the results offer guidance to botanical garden administrators, tourism communities, and decision-makers in developing strategies, planning investments, and promoting content with the greatest potential for tourism development. In this way, the research supports the advancement of sustainable tourism, diversification of offerings, and increased awareness of the importance of preserving natural heritage.

The use of botanical gardens for tourism purposes should enrich the tourist offer of Split–Dalmatia County, as the basis of the offer is already centered on the sea and the sun. In this way, a balanced development of this county would be achieved through the development of tourist offers based on ecology and sustainability in the function of protecting natural resources. The obtained research results showed that botanical gardens have great potential for use in tourism. In this way, the development of botanical tourism helps the local community achieve additional benefits while also preserving biodiversity. Additionally, other interest groups will also benefit from this form of tourism, as botanical gardens serve various functions. The most important thing is that these gardens are part of a model for the sustainable transformation of tourism, aiming to develop sustainable tourism and promote the natural resources of a particular tourist destination.

However, it is important to recognize that this research has certain limitations. First, it is geographically limited to Split–Dalmatia County, so the results and rankings of the botanical gardens cannot be directly applied to all gardens in Croatia or elsewhere. Additionally, while the evaluation criteria were based on a literature review, some relevant factors—such as digital presence, marketing efforts, or financial sustainability—may not have been included. The methodology also relies on subjective assessments by tourism experts, which may introduce perceptual bias; however, their expertise offers credibility. Finally, the attractiveness of botanical gardens can change over time due to factors like seasonality, new investments, infrastructure upgrades, or changes in offerings.

Given the limitations mentioned earlier, future research should expand the scope to include a national or international perspective and compare different types of botanical gardens, arboretums, and related green attractions. Additionally, incorporating more criteria, such as economic indicators, the extent of digital marketing, or visitors’ perceptions, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the tourism value of these gardens. A longitudinal approach is also recommended, as it would enable monitoring of changes in the appeal of botanical gardens over time, particularly in light of new investments and shifts in tourist demand. This expanded framework would support the development of detailed strategies for promoting the tourism valorization of botanical gardens at the regional and national levels.