Reimagining Natural History Museums Through Gamification: Time, Engagement, and Learning in Teacher Education Contexts

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Gamification as an Active Learning Strategy in Education: Concepts and Distinctions

1.2. Gamification in Informal Learning Spaces: Museums and Heritage Contexts

1.3. Gamification in Teacher Education Through Heritage-Based Experiences

1.4. Research Question and Objectives

- To compare students’ estimated time perceptions before and after the visit, evaluating potential changes based on the nature of the experience.

- To contrast the outcomes of the gamified experience with those of the traditional one, considering participants’ academic level.

- To assess students’ knowledge of the museum prior to and following the visit, to evaluate the impact of gamification on learning outcomes.

- To reflect on the pedagogical implications of the findings, particularly in relation to teacher training and heritage education.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and General Approach

2.2. Participants

- Group 1: 33 undergraduate students in Early Childhood Education (traditional visit, control group).

- Group 2: 21 undergraduate students in Early Childhood Education (gamified visit).

- Group 3: 24 graduate students from the Master’s in Secondary Education Teaching (specialization in arts) also engaged in a gamified visit.

2.3. Intervention Context

2.4. Procedure and Instruments

- Coordination with the museum staff was established to schedule the three visits and inform personnel of the nature and structure of each visit type.

- A consistent visit structure was implemented across groups to ensure comparability. Each session began with the pre-test, completed simultaneously and independently by all participants.

- During the visit—whether traditional or gamified—the author documented the session. In the gamified version, students were divided into teams and assigned specific roles. Gamification elements included playful mechanics such as “powers” (strategic advantages), which allowed participants to exchange members, block competitors, or nullify other teams’ points. These mechanics encouraged collaboration and competition, enhancing student engagement.

- Challenges included on-site drawing tasks, location-based puzzles, and knowledge-based questions, all scored with points. Bonus points were awarded for completing specific challenges to further motivate participants.

- The traditional visit followed a conventional educational format led by a museum educator, who provided standard explanations of the exhibits. All key content covered in the gamified sessions was also included in the traditional version to ensure content equivalence across groups.

- At the end of each visit, the post-test was administered, and its timestamp recorded the official end time of the activity.

- Finally, outside the recorded timeframe, a debriefing session was conducted with the future teachers to reflect on the dynamics of the activity and discuss the relevance of gamification in heritage education.

2.5. Data Analysis

- Descriptive statistics.

- Student’s t-tests for paired and independent samples.

- One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

- Non-parametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis), depending on assumption checks.

- Effect size calculations (Cohen’s d and partial eta squared).

- Post hoc comparisons (Tukey and Dunn tests).

3. Results

3.1. Actual Visit Duration

3.2. Perceived Time: Pre–Post Comparison

3.3. Change in Knowledge and Teacher Self-Perception

3.4. Interest, Satisfaction, and Activity Evaluation

- Q1: Was the visit interesting?

- Q2: Did you enjoy the activity?

- Q3: Do you consider this activity suitable for your future students?

- Q4: How much do you think your future students would enjoy it?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | one-way analysis of variance |

| HSD | Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference |

Appendix A

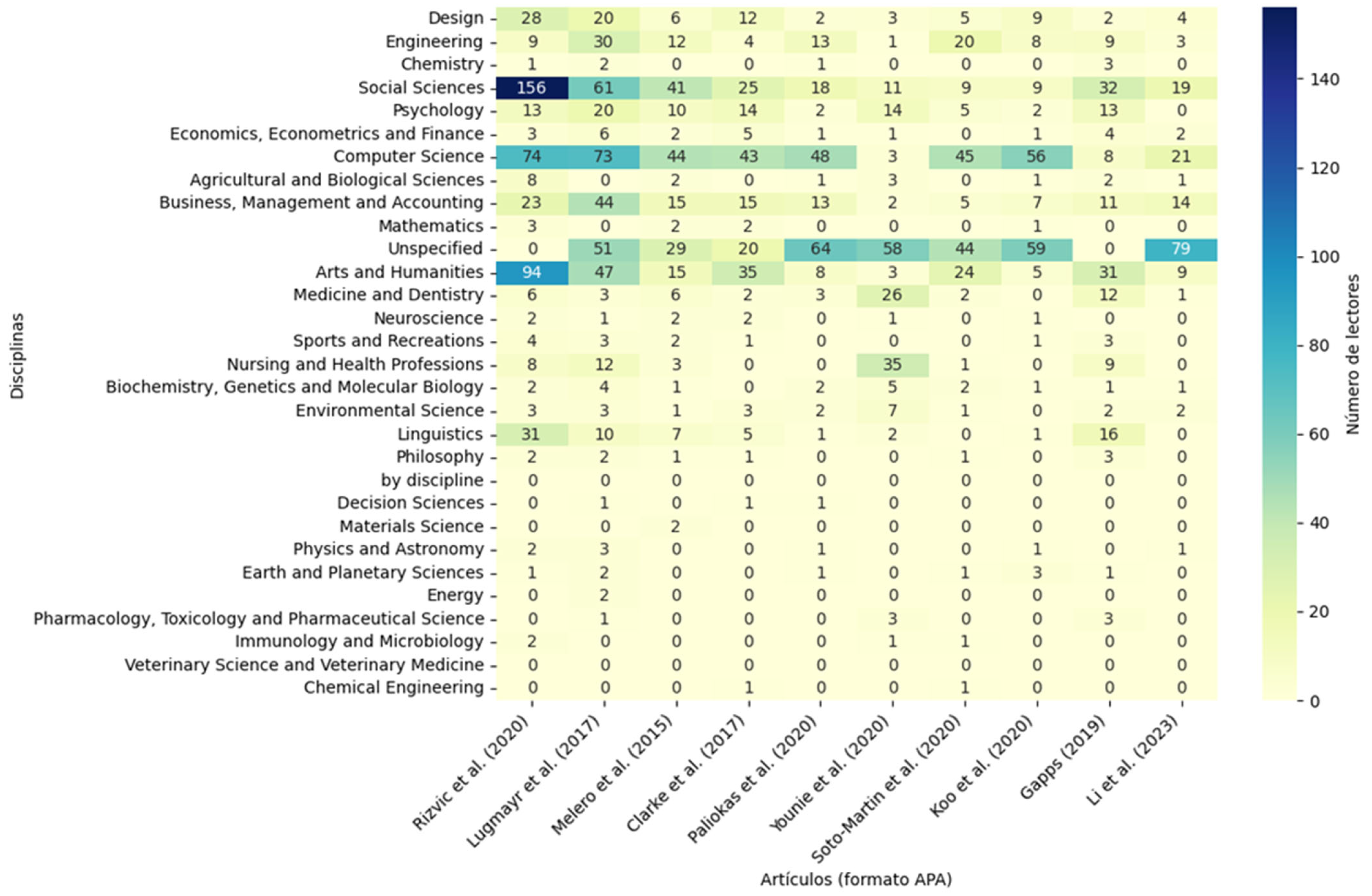

References

- Ellinger, J.; Mess, F.; Bachner, J.; von Au, J.; Mall, C. Changes in Social Interaction, Social Relatedness, and Friendships in Education Outside the Classroom: A Social Network Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1031693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abril-López, D.; López Carrillo, D.; González-Moreno, P.M.; Delgado-Algarra, E.J. How to Use Challenge-Based Learning for the Acquisition of Learning to Learn Competence in Early Childhood Preservice Teachers: A Virtual Archaeological Museum Tour in Spain. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 714684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W. Locating and Designing Participatory Conservation in the Museum: An Analysis of Chinese Practices. Int. J. Educ. Humanit. 2022, 9, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.; Conway, W.; Reading, R.P.; Wemmer, C.; Wildt, D. Evaluating the Conservation Mission of Zoos, Aquariums, Botanical Gardens, and Natural History Museums. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Yulfo, A. Transforming Museum Education Through Intangible Cultural Heritage. J. Mus. Educ. 2022, 47, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Cano, M.; Gil-Ruiz, P.; Martínez-Vérez, V. Visual arts museums as learning environments in the undergraduate and postgraduate programmes of the Faculty of Education at the Complutense University of Madrid. Int. Rev. Educ. 2025, 71, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tserklevych, V.; Prokopenko, O.; Goncharova, O.; Horbenko, I.; Fedorenko, O.; Romanyuk, Y. Virtual museum space as the innovative tool for the student research practice. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2021, 16, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Chiou, S.-C. An Analysis of the Sustainable Development of Environmental Education Provided by Museums. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabamona, J.; Dabamona, S.A. An Exploration of Participants’ Views and Experiences of Cultural Museums and Their Challenges. Gelar J. Seni Budaya 2023, 21, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 29–30 September 2011; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krath, J.; Schürmann, L.; von Korflesch, H.F.O. Revealing the theoretical basis of gamification: A systematic review and analysis of theory in research on gamification, serious games and game-based learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 125, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, J.; Hamari, J. The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 45, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, M.; Homner, L. The gamification of learning: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 32, 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-García, S.; Aznar-Díaz, I.; Cáceres-Reche, M.P.; Trujillo-Torres, J.M.; Romero-Rodríguez, J.M. Systematic Review of Good Teaching Practices with ICT in Spanish Higher Education Trends and Challenges for Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, D.; Skulmoski, G.J.; Fisher, D.P.; Mehrotra, V.; Lim, I.; Lang, A.; Keogh, J.W.L. Drivers and barriers to the utilisation of gamification and game-based learning in universities: A systematic review of educators’ perspectives. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2023, 54, 1748–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciarotti, C.; Bertozzi, G.; Sillaots, M. A New Approach to Gamification in Engineering Education: The Learner-Designer Approach to Serious Games. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 46, 1092–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaldi, A.; Bouzidi, R.; Nader, F. Gamification of E-Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Smart Learn. Environ. 2023, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Gamification for Educational Purposes: What Are the Factors Contributing to Varied Effectiveness? Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 891–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-González, M.E.; López Belmonte, J.; Segura-Robles, A.; Fuentes Cabrera, A. Active and Emerging Methodologies for Ubiquitous Education: Potentials of Flipped Learning and Gamification. Sustainability 2020, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melero, J.; Hernández-Leo, D.; Manatunga, K. Group-Based Mobile Learning: Do Group Size and Sharing Mobile Devices Matter? Comput. Human. Behav. 2015, 44, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofal, E.; Panagiotidou, G.; Reffat, R.M.; Hameeuw, H.; Boschloos, V.; vande Moere, A. Situated tangible gamification of heritage for supporting collaborative learning of young museum visitors. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2020, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangamuang, S.; Wongwan, N.; Intawong, K.; Khanchai, S.; Puritat, K. Gamification in virtual reality museums: Effects on hedonic and eudaimonic experiences in cultural heritage learning. Informatics 2025, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Carrasco, C.-J.; Monteagudo-Fernández, J.; Moreno-Vera, J.-R.; Sainz-Gómez, M. Effects of a Gamification and Flipped-Classroom Program for Teachers in Training on Motivation and Learning Perception. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotos-Martínez, V.J.; Tortosa-Martínez, J.; Baena-Morales, S.; Ferriz-Valero, A. Boosting Student’s Motivation through Gamification in Physical Education. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, W.; Oates, G.; Schonfeldt, N. Improving retention while enhancing student engagement and learning outcomes using gamified mobile technology. Account. Educ. 2025, 34, 366–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G.; Kinshuk. Virtual reality and gamification in education: A systematic review. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2024, 72, 1691–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvic, S.; Okanovic, V.; Boskovic, D. Digital Storytelling. In Visual Computing for Cultural Heritage; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugmayr, A.; Sutinen, E.; Suhonen, J.; Sedano, C.I.; Hlavacs, H.; Montero, C.S. Serious Storytelling—A First Definition and Review. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 15707–15733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, S.C.; Peckinpaugh, I.K.; Lane, S.P. Negative Emotion (Dys)Regulation Predicts Distorted Time Perception: Preliminary Experimental Evidence and Implications for Psychopathology. J. Pers. 2024, 93, 984–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kübel, S.L.; Wittmann, M. A German Validation of Four Questionnaires Crucial to the Study of Time Perception: BPS, CFC-14, SAQ, and MQT. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhouse, N.; tom Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T. An Experiential View to Children Learning in Museums with Augmented Reality. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2019, 34, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xing, Q.-W.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, L.-Y. Exploring the Influence of Gamified Learning on Museum Visitors’ Knowledge and Career Awareness with a Mixed Research Approach. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Blebil, A.Q.; Dujaili, J.A.; Chuang, S.; Lim, A. Implementation of a Hepatitis-Themed Virtual Escape Room in Pharmacy Education: A Pilot Study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 14347–14359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, A.H.S.; Nacke, L.E.; Chang, M.; Wang, Y.; Yousef, A.M.F. Revealing the hotspots of educational gamification: An umbrella review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 109, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahalan, F.; Alias, N.; Shaharom, M.S.N. Gamification and game based learning for vocational education and training: A systematic literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 1279–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwanto, I.; Wahyudiati, D.; Saputro, A.D.; Laksana, S.D. Research trends and applications of gamification in higher education: A bibliometric analysis spanning 2013–2022. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2023, 18, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Chu, S.K.W.; Shujahat, M.; Perera, C.J. The impact of gamification on learning and instruction: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 30, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuebold, J.; Pearlstein, E.; Shelley, W.; Wharton, G. Preliminary research into education for sustainability in cultural heritage conservation. Stud. Conserv. 2022, 67 (Suppl. 1), 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannakis, M.; Papadakis, S.; Zourmpakis, A.-I. Gamification in Science Education. A Systematic Review of the Literature. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo Durán, A. Propuestas artísticas educativas gamificadas: Una visión dinámica para conocer el patrimonio local en educación superior. Rev. Investig. Pedagog. Arte 2025, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Durán, A. Enhancing artistic heritage education through gamification: A comparative study of engagement and learning outcomes in local museums. Nusantara J. Behav. Soc. Sci. 2025, 4, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Real, J.L.; Uribe-Toril, J.; de Pablo Valenciano, J.; Gázquez-Abad, J.C. Rural tourism and development: Evolution in scientific literature and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 1322–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A. Social Justice Education and the Role of Museums. Mus. Soc. 2020, 18, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, M. The Museum Education Department as Training Ground for Scholar-Educators. J. Mus. Educ. 2019, 44, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morentin, M.; Guisasola, J. The Role of Science Museum Field Trips in the Primary Teacher Preparation. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2015, 13, 965–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, B.S.; Mork, S.M. Taking 21st Century Skills from Vision to Classroom: What Teachers Highlight as Supportive Professional Development in the Light of New Demands from Educational Reforms. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 100, 103286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, P.; Öhman, J. Museum Education and Sustainable Development: A Public Pedagogy. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 21, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiş Erümit, S.; Karakuş Yılmaz, T. Gamification Design in Education: What Might Give a Sense of Play and Learning? Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2022, 27, 1039–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, N.M.; Urías, M.D.V.; Salgado, L.N.; Benítez, N.V.; Martínez, M.C.V. Educate to Transform: An Innovative Experience for Faculty Training. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 1613–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Ordorika, A.; Camino-Esturo, E.; Portillo-Berasaluce, J.; Garay-Ruiz, U. Integrating the Maker Pedagogical Approach in Teacher Training: The Acceptance Level and Motivational Attitudes. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 815–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klima Ronen, I. Action Research as a Methodology for Professional Development in Leading an Educational Process. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2020, 64, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascenzi, A.; Brunelli, M.; Meda, J. School Museums as Dynamic Areas for Widening the Heuristic Potential and the Socio-Cultural Impact of the History of Education. A Case Study from Italy. Paedagog. Hist. 2021, 57, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Durán, A. Gamification in the Art World: An Escape Room to Immerse Yourself in the History and Local Artists of the City. In Practices and Implementation of Gamification in Higher Education; Membrive, V., Ed.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Durán, A.; Sánchez-Fuentes, R. Enhancing Artistic Learning Through Gamification: A Case Study in an Archaeology Museum Visit. In Practices and Implementation of Gamification in Higher Education; Membrive, V., Ed.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 114–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.I.; Lee, J.H.; Clark, N. Why video game genres fail: A classificatory analysis. Games Cult. 2017, 12, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliokas, I.; Patenidis, A.T.; Mitsopoulou, E.E.; Tsita, C.; Pehlivanides, G.; Karyati, E.; Tsafaras, S.; Stathopoulos, E.A.; Kokkalas, A.; Diplaris, S.; et al. A Gamified Augmented Reality Application for Digital Heritage and Tourism. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younie, S.; Mitchell, C.; Bisson, M.-J.; Crosby, S.; Kukona, A.; Laird, K. Improving young children’s handwashing behaviour and understanding of germs: The impact of A Germ’s Journey educational resources in schools and public spaces. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Martin, O.; Fuentes-Porto, A.; Martin-Gutierrez, J. A Digital Reconstruction of a Historical Building and Virtual Reintegration of Mural Paintings to Create an Interactive and Immersive Experience in Virtual Reality. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, C.; Kim, J.; Cha, H.S. Development of an Augmented Reality Tour Guide for a Cultural Heritage Site. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2019, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gapps, S. Role-play. In The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wider, W.; Ochiai, Y.; Fauzi, M.A. A bibliometric analysis of immersive technology in museum exhibitions: Exploring user experience. Front. Virtual Real. 2023, 4, 1240562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Mean Duration (min) | Standard Deviation | 95% Confidence Interval | Estimated Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 (Undergraduate + Traditional) | 23.53 | 2.57 | 22.65–24.41 | 20.96–26.1 |

| G2 (Undergraduate + Gamified) | 44.58 | 3.89 | 42.92–46.24 | 40.69–48.47 |

| G3 (Master’s + Gamified) | 46.63 | 5.32 | 44.5–48.76 | 41.31–51.95 |

| Source | DF | Sum of Square | Mean Square | F Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | 2 | 9381.7 | 4690.9 | 302.04 | <0.001 |

| (between groups) | |||||

| Error | 75 | 1164.8 | 15.5 | ||

| (within groups) | |||||

| Total | 77 | 10,546.50 | 137 |

| Pair | Difference | SE | Q | Lower CI | Upper CI | Critical Mean | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1–G2 | 21.05 | 0.78 | 27.06 | 18.42 | 23.68 | 2.63 | <0.001 |

| G1–G3 | 23.10 | 0.75 | 30.90 | 20.57 | 25.63 | 2.53 | <0.001 |

| G2–G3 | 2.04 | 0.83 | 2.46 | −0.77 | 4.86 | 2.82 | 0.1986 |

| Variable | Mean Estimated Time | Mean Difference | Standard Deviation | 95% Confidence Interval | t-Statistic | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pre-test/post-test | 28.7/38.4 | +9.68 min | 14.22 | [6.47–12.89] min | t (77) = 6.01 | d = 0.68 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Mean Pre–Post | Mean Difference | SD | 95% Confidence Interval | t-Statistic | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 1.80–3.10 | +1.34 | 1.16 | [0.93–1.76] | t (32) = 6.63 | 1.15 | <0.001 |

| G2 | 1.80–3.80 | +2.04 | 0.65 | [1.74–2.34] | t (20) = 14.26 | 3.11 | <0.001 |

| G3 | 1.70–3.50 | +1.75 | 0.79 | [1.41–2.08] | t (23) = 10.86 | 2.22 | <0.001 |

| G2 + G3 | 1.70–3.60 | +1.88 | 0.74 | [1.66–2.10] | t (44) = 17.18 | 2.56 | <0.001 |

| Variable | n | Mean/SD | Mann–Whitney | Statistic Z | p-Value (Bilateral) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 pre | 33 | 1.78/0.77 | 751.5 | 0.086 | 0.931 |

| G2, G3 pre | 45 | 1.75/0.17 | |||

| G1 post | 33 | 3.12/0.92 | 503.5 | −2.44 | <0.015 |

| G2, G3 post | 45 | 3.63/0.70 |

| Variable | Q1 Mean/SD | Q2 Mean/SD | Q3 Mean/SD | Q4 Mean/SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 3.03/1.2 | 3.06/1.4 | 2.91/1.4 | 2.76/1.4 |

| G2 | 4.67/0.6 | 4.71/0.6 | 4.00/0.8 | 4.57/0.6 |

| G3 | 4.68/0.7 | 4.46/1.0 | 3.50/1.2 | 4.21/0.8 |

| G2,3 | 4.67/0.6 | 4.59/0.8 | 3.75/1.1 | 4.39/0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galindo-Durán, A. Reimagining Natural History Museums Through Gamification: Time, Engagement, and Learning in Teacher Education Contexts. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2025, 6, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg6030046

Galindo-Durán A. Reimagining Natural History Museums Through Gamification: Time, Engagement, and Learning in Teacher Education Contexts. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens. 2025; 6(3):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg6030046

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalindo-Durán, Alejandro. 2025. "Reimagining Natural History Museums Through Gamification: Time, Engagement, and Learning in Teacher Education Contexts" Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens 6, no. 3: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg6030046

APA StyleGalindo-Durán, A. (2025). Reimagining Natural History Museums Through Gamification: Time, Engagement, and Learning in Teacher Education Contexts. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens, 6(3), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg6030046