Abstract

Botanical gardens play a crucial role in documenting and sustaining traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) that were integral to the lives of Indigenous peoples. TEK has gained significant attention in discussions on sustainable development. Faced with threats to the maintenance and transfer of this knowledge, alternative approaches like community-based ethnobotanical gardens are emerging as effective tools for conservation. This paper details a research partnership that focused on storing and sharing the Bunun ethnic community’s TEK to conserve and promote plant and crop diversity. This collaboration further led to the co-development of an Indigenous ecological calendar detailing knowledge about crops, specifically beans. The ecological calendar emerged as an effective tool for supporting knowledge sharing, facilitating the communication of crop knowledge along with both common and scientific names. The Indigenous ecological calendar has also become a valuable tourism resource for guided tours, helping to build recognition of Indigenous knowledge, and making it accessible to future generations.

1. Introduction

Botanical gardens play a crucial role in documenting and sustaining a wide array of local native plants integral to the lives of Indigenous peoples. Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) encompasses local ways of knowing that emerge from long-term observations of, and interactions with, the living environment [1]. Recognized as critical for conserving biodiversity and the maintaining social-ecological systems [1,2,3], TEK’s importance has been highlighted in international documents like “Our Common Future” [4] and “Caring for the Earth” [5]. TEK gained significant attention at the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), also known as the Rio Summit. Since then, it has been integrated into various international action plans and policies, including the Aichi Biodiversity Targets [6], the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [7], and the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation [8]. This widespread recognition highlights TEK’s essential role in driving global conservation efforts.

The importance of TEK is internationally recognized; however, it concurrently faces erosion, challenged by the biodiversity crisis. The primary causes of TEK’s erosion, such as climate change exceeding its adaptive capacity [9], changing social structures and language shifts disrupting intergenerational knowledge transmission [10], assimilation into market economies forcing the abandonment of traditional practices, and relocation away from vital social-ecological contexts, are well-documented [11,12,13,14,15].

Establishing ethnobotanical gardens can be a tool for preserving living plants and TEK. In related research, Jones and Hoversten, from a garden manager’s perspective, discuss how to design an ethnobotanical garden suitable for visitors [16]. They argue that interpretive activities and environmental design should not oversimplify plants by showing only one aspect, such as edibility or medicinal use. Instead, a clear storyline should allow visitors to understand the history of these ethnobotanical plants, their relevance to local people’s daily lives, and their cultural significance through interpretive activities and environmental experiences.

Innerhofer and Bernhardt’s research focuses on documenting the traditional use of medicinal plants by the Kichwa people in Ecuador and establishing an ethnobotanical garden in a secondary forest for plant conservation [17]. They aim to provide employment opportunities and promote environmental education to help mitigate habitat destruction caused by deforestation and intensive agriculture. A common theme emerges in these few studies on ethnobotanical gardens: the garden must illustrate the relationships between people, plants, and the environment while emphasizing cultural context. As Maunder (2008) highlighted, botanical/ethnobotanical gardens should be developed as resource centers appropriate to the local community’s needs, culture, and climate.

Based on the above TEK discourses and ethnobotanical garden research, this study aims to document and sustain TEK within the Kalibuan ethnic community, which was relocated during the colonial period. Collaborating with the Taipei Botanical Garden (TPBG) and the Indigenous community, we responded to the international call for botanical garden conservation strategies by actively implementing the concept of biocultural conservation [18]. Our efforts involve documenting TEK, the emergence of local ecological knowledge, and establishing an ethnobotanical garden within the Kalibuan ethnic community. This garden serves as a site for education and tourism, focusing on Indigenous plant knowledge. It also acts as a repository for ethnobotanical vouchers available for future research. Additionally, we collaborated with the community to develop two types of brochures: one detailing Bunun hunting knowledge and another on the Bunun ecological calendar. These initiatives aid the Kalibuan community in preserving their cultural and crop diversity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. A Historical Background of the Relocation of the Bunun Ethnic Community

The Bunun are one of the Indigenous highland peoples in Taiwan. They have a population of 6164 individuals, ranking them as the fourth largest Indigenous group in Taiwan [19]. The majority reside in the central section of Taiwan’s Central Mountain Range (Figure 2), which is characterized by an abundance of mountains exceeding an elevation of two thousand meters. Based on earlier Japanese anthropological surveys, the highest-altitude settlement was situated in a mountainous area with an elevation of 2306 m [20].

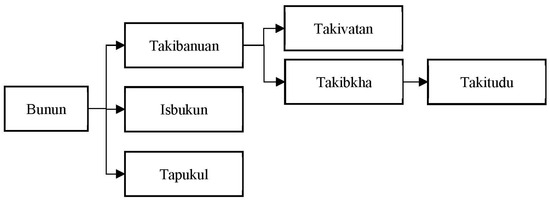

Between 1930 and 1935, Japanese anthropologists Utsurikawa Nenozo, Miyamoto Nobuto, and Mabuchi Toichi conducted a comprehensive investigation on the Indigenous peoples of Taiwan [21]. They interviewed elders born during the Qing Dynasty (1683–1895), recording their oral histories concerning tribal migrations, family genealogies, and interactions with outsiders. According to their findings, the Bunun consists of six branches: Takibanuan, Takivatan, Takibkha, Takitudu, Isbukun, and Tapukul (Figure 1). Takivatan and Takibkha emerged as separate branches from Takibanuan, estimated to have split off around 1630. Takitudu split within the Takibkha sub-branch, occurring approximately around 1680. Tapukul was already on the brink of disappearance during the investigation period, with only 13 individuals remaining, mainly due to an epidemic in 1770 that caused a significant population decline, compounded by interactions and intermarriages with neighboring Tsou people, resulting in the primary adoption of the Tsou language in their daily lives.

Figure 1.

Six branches of the Bunun.

From 1895 to 1945, Taiwan was under Japanese colonial rule. During the period between 1930 and 1940, the colonial government implemented a policy of relocating indigenous communities [22]. By 1939, approximately 62 percent of the Bunun population had been relocated from steep mountainous areas to valleys and foothills [20]. The original six branches of the Bunun, characterized by unique dialects and customs, gradually fragmented into numerous new villages.

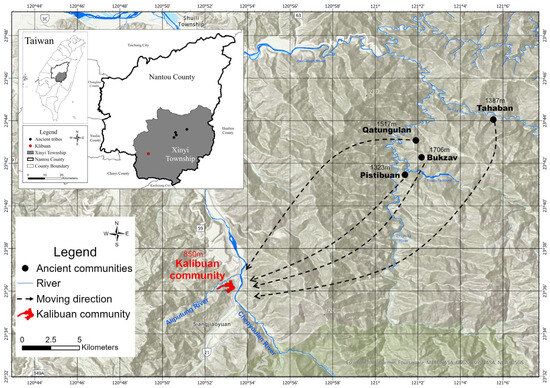

The relocation process from the ancient communities to Kalibuan was completed by 1938 [23]. The residents of Kalibuan community, primarily from the Takibanuan branch, include individuals from four ancient communities: Qatungulan, Bukzav, Pistibuan, and Tahaban [24]. These communities were originally located at elevations ranging from approximately 1300 m to 1700 m (Figure 2). After the relocation was completed, these four ancient community areas became uninhabited. The Kalibuan community is situated on the western side of the middle reaches of Chenyoulan River, on a terrace land between the Aliputung River and Hoshe River. The Alipudong River serves as the source of drinking and irrigation water for the residents of Kalibuan.

As of October 2023, the Kalibuan community has a population of 698 people, with 91 percent being members of the Bunun, totaling 636 individuals [19]. During interviews in the community, it was observed that elderly members aged over 80 are fluent in old Japanese and have vivid memories of their relocation experience. According to an interviewee, following the large-scale relocation and before the houses were constructed, the Japanese authorities offered a daily wage of fifty cents to hire community members for tasks such as building houses, clearing land, and working on irrigation projects. It is noteworthy that government officials received a monthly salary of 15 TWD during that period. The 50 cent daily wage was considered relatively high, ensuring that the residents had a decent income. Once the tribal settlements were established, the Japanese authorities guided the residents in rice cultivation and allocated fields based on the labor force available within each household.

Figure 2.

Relocation map of the Bunun in Kalibuan. Note: The map was made by authors, based on data from sources [23,24,25,26,27].

The enforcement of the collective relocation policy resulted in profound transformations in the Bunun community’s social structure and subsistence patterns [25,26,27]. Historically, the Bunun people sustained themselves through a self-sufficient system of agriculture and hunting, cultivating crops like millet, sweet potatoes, taro, pigeon pea, and various legumes [28,29,30]. However, the introduction of cash crops during Japanese colonial rule fundamentally altered in the indigenous land management practices, daily routines, and ceremonial customs [26,27]. As a result, community members gradually abandoned their traditional hillside-swidden cultivation methods for millet, shifting instead to more intensive agricultural practices on flat terrain.

The changes in livelihood significantly disrupted the traditional social organization of the Bunun. In the traditional Bunun society, governance was carried out by the elders who led and guided decisions regarding tribal rituals, expeditions, and other important matters [30]. However, the shift from traditional cultivation of millet and legumes to rice, which became the primary staple food, led to a gradual disappearance of various traditional rituals and ceremonies [26]. This change diminished the significance of related ritual activities, resulting in the loss of social status for traditional Bunun leaders [26]. Furthermore, the relocation from high mountain areas to lower elevations exposed community members to malaria, a disease that traditional healers were unable to cure [23,31]. This exposure also impacted the belief system of the Bunun [23,31].

During the Japanese colonial period, land was confiscated and placed under state ownership. To facilitate effective relocation and promote settled agriculture, the ruling authorities distributed and utilized land rights, disrupting the traditional territorial divisions of the Bunun community [32]. Another change involved the spatial arrangement of new houses. Traditionally, Bunun houses were often dispersed and distant from each other, with only closely related families living in close proximity in a small clustered pattern [29]. However, as part of the Japanese relocation policy for administrative convenience, residential areas were organized in a grid-like configuration near police stations [32]. Additionally, the new houses had smaller living spaces, leading to the fragmentation of large traditional Bunun households into smaller nuclear families [32].

2.2. Changes in the Livelihoods of the Kalibuan Community

After the government relocated the Bunun, the social and economic development of the Kalibuan community became closely intertwined with mainstream society. According to community pastor Yohani Isqaqavut, the changes in livelihoods within the Kalibuan community can be broadly categorized into several stages. In the 1940s, the primary crops in the Kalibuan community were still traditional ones such as millet, corn, sweet potatoes, taro, and beans. During this period, the Japanese began teaching the tribal members how to use water buffaloes for paddy rice cultivation. It marked the first time the community engaged in the cultivation of the introduced crop.

By the 1950s, members of the community had become adept at rice cultivation techniques, leading to a shift in their staple food from traditional crops to rice. They also began cultivating bananas for export to Japan, shipping them once a week. This shift provided the residents with a stable source of income and significantly improved their quality of life. Additionally, Japan’s demand for lemongrass oil prompted the community to extensively grow lemongrass for export.

During the 1960s, the government encouraged the community to cultivate pears. Initially, the prices were favorable, prompting many individuals to engage in pear farming. However, as the market became oversaturated with pears from various parts of Taiwan, the prices sharply decline. This downturn led to significant financial losses for many pear farmers, forcing them to ultimately remove their pear trees entirely. It was a challenging period for the community’s economy, marked by significant hardships.

By the 1970s, the main economic crops in the community were maize and plums. However, in the 1980s, the price of plums dropped significantly, prompting the community to shift their focus to higher-priced crops such as beefsteak tomatoes, cherry tomatoes, green beans, and bell peppers. In recent years, due to drastic climate changes and heavy rainfall in mountainous areas, the community began greenhouse cultivation in the 1990s, transitioning towards modernized agriculture (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The greenhouse cultivation of the Kalibuan community.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

This study can be divided into two phases: the first is an intensive data collection, and the second involves data application. The study commenced with a review of historical literature to elucidate the tribal migration and the evolution of socio-economic dynamics. From 2016 to 2018, coinciding with a project aimed at establishing a community-based ethnobotanical garden to bolster local plant conservation capabilities, on-site interviews were undertaken.

Before conducting the interviews, the authors first reached out to the Community Development Association. After securing consent from the chairman, the authors were scheduled to present at the community’s Sunday church services. This presentation aimed to inform residents about the upcoming interviews on ethnobotanical knowledge, which would be conducted in collaboration with the Taipei Botanical Garden. During the presentation, the chairman also provided simultaneous translations into the Bunun language for the elder members of the community. We selected community members familiar with ethnobotanical plants through snowball sampling [33], choosing those who were willing to participate in the study.

A total of 24 interviewees participated, ranging in age from 34 to 86 years. Among them, 22 were men and only 2 were women; the main reason being that men are more familiar with the forest and skilled at identifying wild plants, and were more willing to accompany the researchers to the forests surrounding the community. Women in the community tended to work in the farmlands and family gardens near their homes. Regarding the ages of the interviewees, among the men, three were aged 30–40, five were aged 40–50, six were aged 50–60, six were aged 70–80, and two were aged 80–90. For the women, both were aged 70–80.

We conducted semi-structured interviews [34] with open-ended questions following a general guide about the Bunun’s ethnobotanical plants. The guide included the Bunun names of plants, their habitats, interactions with plants, related traditions, ceremonies, cyclical events, and taboos. For elders not fluent in Chinese, we enlisted the help of community members fluent in the Bunun language to accompany us during interviews. They assisted by translating from Chinese to Bunun, ensuring that the elders could understand our questions.

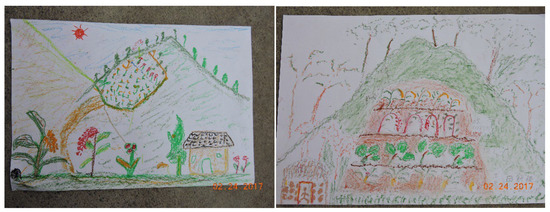

To accommodate elderly community members with mobility constraints, we employed an art-based method involving collage and drawing to facilitate interactive interviews [35]. This approach encouraged elders to share their memories and experience of TEK through drawing and crafting and served as a means to amplify their voices. Such methods are considered appropriate as part of decolonizing methodologies [36,37]. A workshop, which consisted of two sessions, was organized at the community’s elder care facility. It included eight participants, four women and four men, aged between 60 and 85. These eight participants were not among the 24 interviewees previously mentioned. During the first session, participants were prompted to depict their home gardens and partake in a seed-planting activity using a wooden frame provided by the researchers. This session facilitated a discussion on planting preferences and a collaborative effort in plant arrangement. The second session provided the elders materials to create drawings depicting the path from their homes to their fields. Following the completion of their drawings, the elders presented and discussed their artworks with the group.

For the data application of TEK within the community, we partner with women to co-create an ecological calendar, also referred to as natural or phenological calendars. These are knowledge systems that measure and interpret time based on detailed observation of the surrounding environment [38,39]. The indicators in these calendars are closely linked to agricultural activities, enabling communities to determine the best timing for their work. There was a total of nine female participants involved, including two aged over 90, three over 80, two over 70, and one each in their 60s and 50s.

For the three research methods—semi-structured interviews, art activities, and the ecological calendar—the number of participants is detailed in Table 1. Data from these three methods were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. We utilized conventional content analysis [40] to examine the emergence of local ecological knowledge and TEK, which is an approach commonly used to describe explicit information in any form of communication.

Table 1.

Three sets of participants were engaged in the three research methods.

3. Results

3.1. Documenting Traditional Ecological Knowledge

3.1.1. The Emergent Knowledge

TEK should not be considered a static concept or isolated from other knowledge systems [41,42]. It is both cumulative and dynamic, building on experiences and adapting to changes, thus enabling indigenous people to cope with social-ecological changes. This adaptability increases the sustainability of their practices and fosters social-ecological resilience [43]. While numerous researchers have highlighted that factors such as environmental changes [18] and shifts in livelihood practices can lead to the loss of TEK, other studies have found that TEK may also expand and transform [43,44]. In Kalibuan, we have observed that life experiences significantly shape their knowledge of plants, a phenomenon consistently observed in our fieldwork. Although the Kalibuan community’s formation resulted from forced relocation by the colonial government, discussing TEK from the perspective of dynamic changes shows how knowledge expands and evolves as community residents adjust to changing living environments. For instance, the Cowpea (Vigna umbellata), is referred to as “Benus tanaul” in the Bunun language, with “Tanual” meaning “beans of the Tsou people”. These beans come in green, red, and brown varieties. Originally, Kalibuan was inhabited by the Tsou people. During the Japanese colonial period, the Tsou were relocated to Alishan, and the Bunun was subsequently moved from the mountains to the area. As elders in the community cultivated the land, these beans began to grow naturally. Due to their slow growth rate, community members plant them alongside millet, allowing them to climb independently. These beans are believed to possess medicinal properties such as alleviating stomach pain.

In addition, interactions between Kalibuan residents and other ethnic groups have led to the emergence of local ecological knowledge. For example, Vigna radiata, known as “Laian” in the Bunun language, is associated with folklore. It is said that in ancient times, a Bunun individual visited the territory of the Siraya for trade. While there, the Bunun person tasted the local mung beans and found them delicious. He wanted to bring the seeds back to his community, but the Siraya people were reluctant to share them. To smuggle the mung beans, the Bunun individual concealed them in various body parts such as his hair, ears, mouth, and nails. However, the Siraya people discovered these hiding places. In a final attempt, the Bunun person hid the mung beans in his foreskin. The Siraya people hesitated to inspect this particular body part out of embarrassment, allowing the Bunun person to successfully bring the mung beans back to his community. From then on, the Bunun had mung beans. The name “Laian” is used for these beans because they originated from the Siraya.

Interactions with the mainstream society’s economic trading activities can also be inferred from how ethnic communities name plants. For example, Speckled Kidney Beans (Phaseolus coccineus) are called “bulavaz sui” in the Bunun language. The term “bulavaz” refers to the flat shape of the beans, while “sui” has two possible origins. The first origin is from its association with “money”, reflecting the use of Speckled Kidney Beans for trading and exchanging with people outside the community, thus underscoring their value as a form of currency. The second origin comes from the Minnan dialect, where the word for “beautiful” sounds similar to “sui”. This link to beauty led to the adoption of the name. In the Kalibuan, there are three varieties of Speckled Kidney Beans: light-colored, dark-colored, and a rounder, sweeter variety known as “bulavaz namboh”. Traditionally, these beans are cultivated alongside with millet and sorghum.

3.1.2. Observation of the Natural Environment

Another naming convention for ethnic communities involves combining the pronunciation of a plant name with another root word or adjective. For example, in Kalibuan—“kalibu” is related to Myrica rubra, commonly known as Yangmei or Chinese bayberry. In Izukan—the presence of “izuk” in the name suggests that citrus fruits, such as pomelos or oranges, are prevalent in the community. In Dadakus—the abundance of “dakus” in the name indicates that camphor trees are common in the area. Similarly, in Masudala—the reference to “dala” suggests that maple trees could be found in the Masudala ethnic community.

3.1.3. Observation of Plant Growth Characteristics

In the workshop, all participating elders adopted a mixed-cropping strategy, where various crop species were planted together on a single plot. The arrangement of the bean planting locations took into account growth speed and height. For example, a row of millet seeds was planted adjacent to a row of red quinoa to ensure that shorter crops received adequate sunlight. The plot accommodated six to eight plant species. Additionally, the ripening rate was a factor in the seed allocation strategy. Elders placed at least three varieties of beans in the same hole (Figure 4), each with different growth rates.

Figure 4.

Collage expression of three species in one hole.

Certain leguminous plants are particularly well-suited for cultivation along field edges, as their names often reflect their growth habits. For example, Lablab purpureus (L.) Sweet, locally known as Bulavaz Sila, is a short-lived summer-growing annual forage legume. The term “Sila” translates to “side edge”. This plant is characterized by twining, climbing, trailing, or upright herbaceous growth, and can reach 3–6 m lengths. The vines exhibit rapid growth and tend to entwine around other plants. Consequently, elders traditionally planted these beans at the edge of the field to accommodate their growth pattern.

3.1.4. The Criteria for Site Selection

The Bunun people typically choose their dwellings and agricultural plots on slopes flanking tributaries, strategically avoiding the dampness of valleys and the risk of flooding during heavy rain, while benefiting from the natural defensibility of steep slopes [24]. According to the paintings by the elders, these slopes are primarily eastward-facing, capturing the first morning sunlight (Figure 5); however, some elders also mention the use of west-facing slopes. Regardless of the orientation, there is a strong emphasis on the necessity of ample sunlight, which is crucial for the growth of millet. Regarding slope gradient selection, research by Lumaf [24] shows that the Bunun people use an experimental method in which they place stones on an uphill slope and observe where the stones naturally come to rest while rolling downhill to determine suitable areas for habitation. This practice is similar to the concept of the angle of repose [45], which represents the stable angle a slope maintains once erosion or landslides have ceased.

Figure 5.

The agricultural lands of the Bunun are often selected on slopes that receive ample sunlight.

3.2. Sustaining Traditional Ecological Knowledge

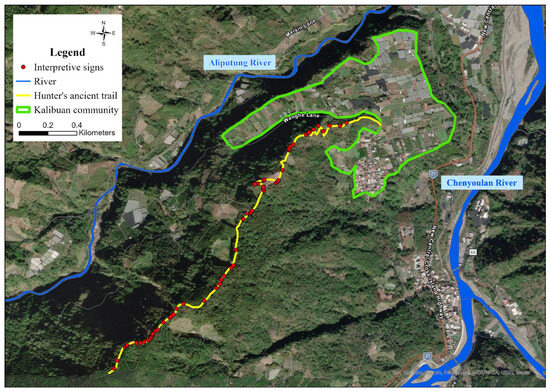

After experiencing relocation and changes in industries, the current lifestyle of the Kalibuan community is vastly different from its traditional way of life, and TEK has gradually declined. We are actively to collaborating with residents to explore how the collected TEK can be applied within the community. Considering their current livelihood, in addition to agriculture, the Kalibuan community is also focusing on developing cultural tourism. Establishing a community-based ethnobotanical garden has become a priority in line with these cultural tourism initiatives. The location and selection of culturally significant plants for this garden were guided by recommendations from the community association’s members and church pastors. This garden is located to the southwest of the community, along the hunter’s ancient trail (Figure 6). Once a frequented route for community hunters, this area has now been transformed into a hiking trail for tourists. From the highest points on the trail, a view of the entire community is visible.

Figure 6.

The Kalibuan community’s ethnobotanical garden is located to the southwest of the community along hunter’s ancient trail.

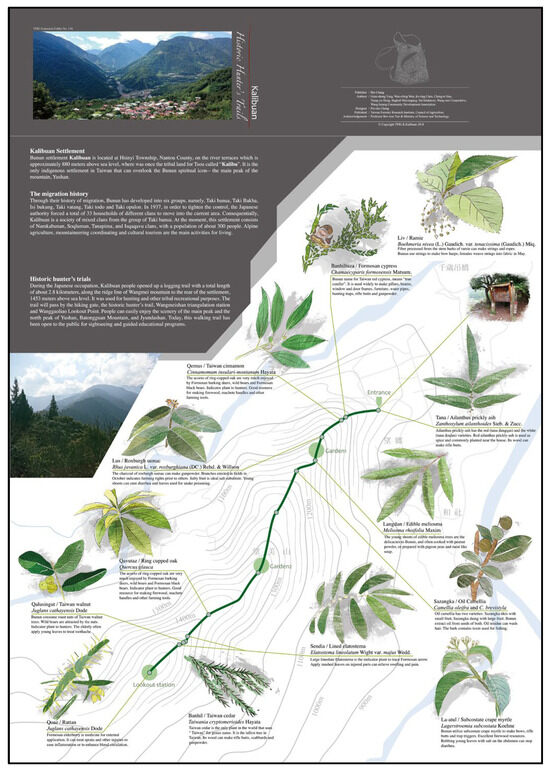

The trail extends for approximately 3 km. Colleagues from the Taipei Botanical Garden (TPBG) used GPS technology to document the coordinates of each plant. In collaboration with local residents, TPBG identified 104 species, recording the plants’ Bunun names and usages and discerning and confirming their scientific and Chinese names. Beyond integrating this gathered Bunun ethnobotanical knowledge into TPBG’s traditional ecological knowledge online database, TPBG transformed this plant information into interpretive signs (Figure 6 and Figure 7) placed along the trail and included some culturally significant plants in brochures (Figure 8). Consequently, this repository of ethnobotanical knowledge has been incorporated into educational materials for tourist guides and interpretive resources. Within the community-based ethnobotanical garden, the residents manage plant care, while TPBG serves in a supportive and advisory role, helping the community address plant pests and diseases.

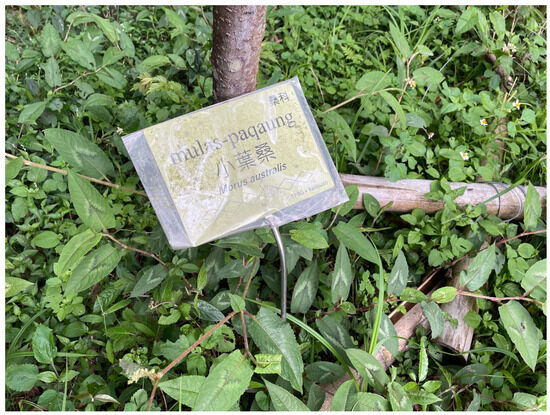

Figure 7.

The interpretive sign for the ethnobotanical plant includes names in Bunun, Chinese, and botanical (Latin).

Figure 8.

Brochure for the Kalibuan community ethnobotanical garden.

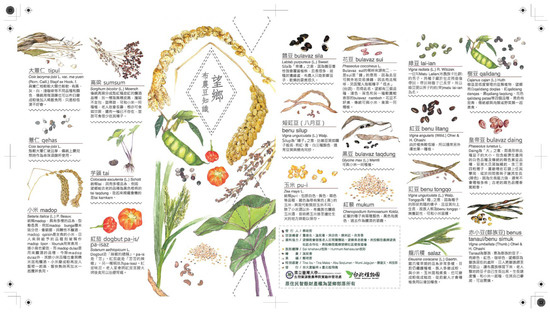

The second part focuses on women’s agricultural knowledge. Through interviews and observations of the elders’ home gardens, we discovered that women possess particularly abundant knowledge about “beans”. Although beans no longer play a significant role in the diet of the Bunun people as they once did, they remain an important food in the elders’ memories (refer Figure 9 for an example). Additionally, a few elderly members of the community continue to cultivate beans persistently because they yearn for the flavors remembered from their memories.

Figure 9.

Grandma Ibu cooked bean soup for the authors. This soup contained many different types of beans, stewed together with pork ribs, ginger, and various indigenous spices.

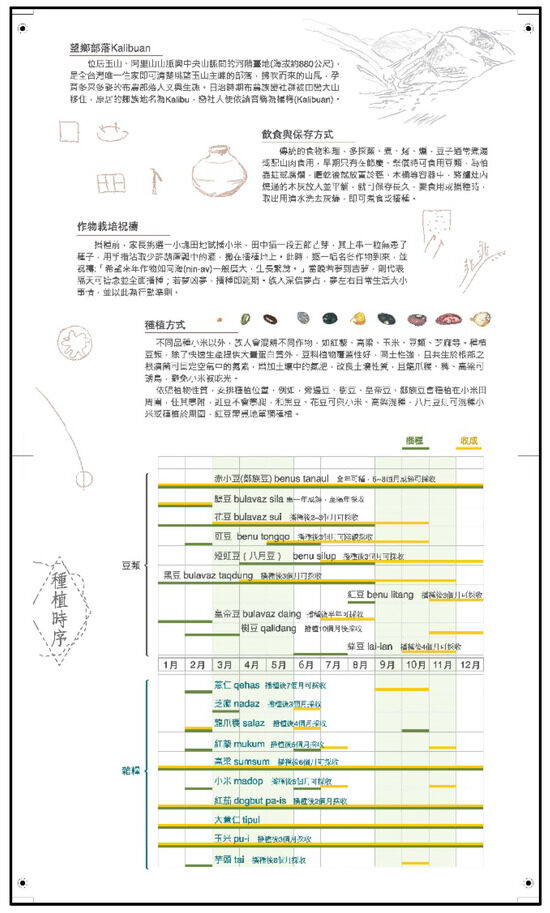

In the Kalibuan community, Grandma Ibu, known for cultivating the most diverse varieties of beans, shared with us, “I grow beans, not for profit, so anyone in need can come and take them. If fellow community members need them, I tell them to come and harvest. When guests visit the community, we usually prepare delicious dishes to entertain them. At these times, people often think of my beans and come to me to get some to cook with. It always brings me joy whenever they use these beans to prepare tasty dishes”. With this sentiment in mind, we aim to preserve the knowledge shared by the community elders through workshops by creating an ecological calendar. This ensures that the knowledge about beans can be passed down in written form (Figure 10 and Figure 11). Currently, the community also uses this ecological calendar in tourism guide brochures.

Figure 10.

Women’s crop knowledge brochure in Chinese (front side). This brochure includes descriptions of each crop’s variety and appearance, the origins of their names, methods for planting and preservation, and details on how they are used in cooking and their flavors.

Figure 11.

Women’s crop knowledge brochure with ecological calendar in Chinese (back side). The content includes the planting and harvesting months for each crop.

4. Conclusions

TEK is inherently dynamic and rooted in Indigenous oral history. The Bunun people, relocated from high mountain regions to lower elevations by the colonial government, experienced significant losses in TEK. However, we observed the emergence of local ecological knowledge post-relocation, as evidenced by the names of plants and crops within the Kalibuan community.

Community-governed ethnobotanical gardens can serve as tools for both plant and knowledge conservation, aiding Indigenous communities in documenting plant usage and recording gathering areas. The Kalibuan ethnobotanical garden, located along their ancient hunting trail, remains a culturally significant space for the Bunun people. Though it now functions as a hiking trail for tourists, it retains its cultural importance. The garden addresses the community’s cultural preservation needs and complements Kalibuan’s active development of Indigenous tourism. Additionally, it acts as a repository for ethnobotanical vouchers [46], providing a resource for future researchers studying ethnobotanical plants.

Documenting and sustaining TEK in-situ was crucial in providing opportunities for broader community members to engage in cultural preservation. This process allowed them to discuss their ecological observations with those directly involved in producing the ethnobotanical garden’s brochure and ecological calendar, and to develop a broader sense of ownership over the final products. This approach supports the idea, as noted by Dunn [18], that effective conservation efforts should address the connections between biological, cultural, and linguistic diversity, thereby embodying the concept of biocultural conservation.

Botanical gardens have many opportunities to bring diverse communities together through a shared interest in plants and empower communities to take greater control over their lives. They can position themselves as a voice of authority on biocultural conservation. In this way, it aligns with and helps achieve Target 14 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC), which aims to raise awareness about the importance of plant diversity and the necessity of its conservation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.-H.H., C.-L.C. and G.-S.T.; methodology, C.-L.C.; investigation, P.-H.H., C.-L.C. and G.-S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.-H.H.; writing—review and editing, P.-H.H.; supervision, G.-S.T. and C.-L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council, grant number MOST 105-2119-M-054-001-MY2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University (code NTU-REC 201909HS001).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to our Bunun friends who made this study possible. We are especially grateful to the elders who shared their knowledge and experiences during the process. The authors would also like to thank research assistants Wan-Ching Wen and Tsung-Yu Hung who help with data collection and tour facilitation. Sincere thanks to five anonymous reviewers whose thoughtful comments improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

References

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, S.; Goswami, M. Role of traditional ecological knowledge on field margin vegetation in sustainable development: A study in a rural-urban interface of Bengaluru. Trees For. People 2022, 8, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, K.; Kamura, K. Traditional Ecological Knowledge Maintains Useful Plant Diversity in Semi-natural Grasslands in the Kiso Region, Japan. Environ. Manag. 2020, 65, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN; UNEP; WWF. Caring for the Earth: A Stragety for Sustainable Living; IUCN, UNEP, WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Aichi Biodiversity Targets. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/ (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Global Strategy for Plant Conservation. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/gspc/targets.shtml (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Dunn, C.P. Climate Change and Its Consequences for Cultural and Language Endangerment. In The Oxford Handbook of Endangered Languages; Rehg, K.L., Campbell, L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 720–738. [Google Scholar]

- Benz, B.F.; Cevallos, E.J.; Santana, M.F.; Rosales, A.J.; Graf, M.S. Losing knowledge about plant use in the sierra de manantlan biosphere reserve, Mexico. Econ. Bot. 2000, 54, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, J.A. Interaction between Biological and Cultural Diversity. In Indigenous Peoples, Environment and Development; Büchl, S., Erni, C., Jurt, L., Rüegg, C., Eds.; International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) & Department of Social Anthropology, University of Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 1997; pp. 173–196. [Google Scholar]

- Maffi, L. Maintaining and Restoring Biocultural Diversity: The Evolution of a Role for Ethnobiology. Adv. Econ. Bot. 2004, 15, 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Maffi, L. (Ed.) On Biocultural Diversity: Linking Language, Knowledge, and the Environment; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maffi, L. Linking Language and Environment: A Co-Evolutionary Perspective. In New Directions in Anthropology and Environment: Intersections; Crumley, C.L., Ed.; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 24–48. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, D. Losing species, losing languages: Connections between biological and linguistic diversity. Southwest J. Linguist. 1996, 15, 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.B.; Hoversten, M.E. Attributes of a Successful Ethnobotanical Garden. Landsc. J. 2004, 23, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innerhofer, S.; Bernhardt, K.-G. Ethnobotanic garden design in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 20, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, C.P. Biological and cultural diversity in the context of botanic garden conservation strategies. Plant Divers. 2017, 39, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Household Registration Ministry of the Interior. April Statistics on Indigenous Population 2023. Available online: https://www.ris.gov.tw/app/portal/346 (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Chen, C.-H.; Sun, T.-H.; Tsai, H.-K. Taiwan’s Population; SMC Publishing Incorporated: Taipei, Taiwan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Taihoku Imperial University’s Department of Ethnology and Folklore Research Survey. The Formosan Native Tribes: A Generalogical and Classificatory Study; Council of Indigneous People: Taipei, Taiwan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Palalavi, H. Origin and Tribal Migration History of the Bunun Tribe; Council of Indigenous Peoples: Taipei, Taiwan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, K.-H. The Impact of Collective Relocation Policy on Social Networks of Indigenous People: The Case of Nitaka Gun. Taiwan Hist. 2013, 64, 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Taiwan Sotokufu Keimukyoku. The Household Registration Records of the Savages; Taiwan Sotokufu Keimukyoku: Taipei, Taiwan, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, K.-H. Divide and rule: Social networks and collective relocations of Bunun and Pan-Atayal tribes, 1931–1945. Taiwan Hist. Res. 2016, 23, 123–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-F. A Research on the Bunun’s Collective Movement at Nan-tou Area in the Period of Japanese Dominance. Master’s Thesis, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji, K. Taiwan under Colonial Rule: Developmentof Public Opinion about Savage That Had no Sovereignty; Hontosho Senta: Tokyo, Japan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, G.-S.; Huang, C.-R.; Haivangang, B. Wander Lamuan: The Ethnobotany of Bunun in Formosan Central Ridge; Forestry Bureau, Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan: Taipei, Taiwan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.-C. Social Organization of the Take-Bakha Bunun; Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica: Taipei, Taiwan, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.-K. The Bunun; San Min Book Co., Ltd.: Taipei, Taiwan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-W.; Teng, T.-T. The Spatial Transformation of Tonpu (1945–1990). Taiwan A Radic. Q. Soc. Stud. 1991, 3, 51–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.-H. Tribes Migration and Social Reconstruction of Taiwan Aborigines in Japan Colonial Period: The Case Study of the Bunun of Be-nan River; National Taiwan Normal University: Taipei, Taiwan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 6th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, S.; Davison, C.M.; Malla, M.; Bartels, S.; Collier, K.; Plamondon, K.; Purkey, E. Biographical Collage as a Tool in Inuit Community-Based Participatory Research and Capacity Development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flicker, S.; Danforth, J.Y.; Wilson, C.; Oliver, V.; Larkin, J.; Restoule, J.-P.; Mitchell, C.; Konsmo, E.; Jackson, R.; Prentice, T. Because we have really unique art: Decolonizing research with indigenous youth using the arts. Int. J. Indig. Health 2014, 10, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, C.; Gifford, W.; Thomas, R.; Rabaa, S.; Thomas, O.; Domecq, M.-C. Arts-based research methods with indigenous peoples: An international scoping review. AlterNative Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2018, 14, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, K.-A.S.; Ruelle, M.L.; Samimi, C.; Trabucco, A.; Xu, J. Anticipating Climatic Variability: The Potential of Ecological Calendars. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassam, K.-A.S.; Bulbulshoev, U.; Ruelle, M. Ecology of time: Calendar of the human body in the Pamir Mountains. J. Persianate Stud. 2011, 4, 146–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, A. Indigenous and scientific knowledge: Some critical comments. Indig. Knowl. Dev. Monit. 1995, 3, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V. The Values of Traditional Ecological Knowledge. In Handbook of Ecological Economics; Martínez-Alier, J., Muradian, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 283–306. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. Sacred Ecology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, R.; Gavin, M.C. A classification of threats to traditional ecological knowledge and conservation responses. Conserv. Soc. 2016, 14, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-J.; Zhao, D.; Liang, Y.; Wen, H.-B. Angle of repose of landslide debris deposits induced by 2008 Sichuan Earthquake. Eng. Geol. 2013, 156, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, M. Use of Herbarium Specimens in Ethnobotany. In Curating Biocultural Collections: A Handbook; Salick, J., Konchar, K., Nesbitt, M., Eds.; Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, UK, 2014; pp. 313–328. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).