1. Introduction

The Blue-throated macaw

Ara glaucogularis (Dabbene 1921) is endemic to the Beni savanna in north central Bolivia [

1] and is assessed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN [

2], with the remaining wild population size said to be fewer than 500 individuals [

3]. Threats include illegal poaching, habitat loss, and a lack of breeding sites [

2,

3]. The species is 85 cm in length with a wingspan of 90 cm, and the feather colouration of adult birds is turquoise on the back, crown, and dorsal sides, with yellow on the chest and a turquoise feather patch on the throat, which gives them their name. They have yellow eyes, a black to greyish beak, turquoise tail feathers, a white-feathered face with dark blue feather stripes, and a bare cere [

1,

4,

5]. Their habitat is hot and humid, with average diurnal ambient temperatures ranging from 24 to 32 °C across the year [

6].

Like most birds, macaws possess excellent eyesight, with proportionately large eyes on the sides of the head providing a wide field of vision but a small field of stereovision. The lenses are held in place by the ciliary body that contains striated muscles, and these muscles allow birds to have conscious control over their iris and pupil size; macaws use this to rapidly dilate and constrict pupils in a behaviour termed ‘pinning’ [

7]. Macaws have a thinner cornea and a larger posterior chamber when compared with mammals, as well as a disc-like flat posterior chamber which enables their retinas to have broad visual acuity. Avian retinas are avascular and thick, and the larger number of cones ensures they have good eyesight clarity. Birds also have four types of single cones, which act as photoreceptor cells in their retinas, and these give them their tetrachromatic colour vision, allowing them to discern around 100 million colours, including longer wavelengths in the ultraviolet spectrum (UVA radiation). Macaws rely on this heightened primary sensory system to inform them about their environment and conspecifics, and the function of ultraviolet vision in birds is also thought to be related to orientation, foraging, as well as signalling [

8,

9]. Like reptiles (see [

10]), in addition to wavelengths of light important for vision, birds are also reliant on UVB wavelengths for cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D

3 and, therefore, for calcium homeostasis [

11,

12]. However, unlike in the case of captive reptiles, where artificial lighting provision is relatively advanced [

9], broad-spectrum lighting is not universally used for indoors-housed captive birds, and there is a need for research to underpin changes in practice in this area. Limited published research, which does not focus on psitaccids, showed that the absence of UVA light created the suboptimal condition for birds in general [

13] and proposed that environments where UVA is provided are enriching for birds as their environmental perception is enhanced [

14]. Ross et al. [

15] investigated lighting preferences between supplemental UVA and standard artificial light in 18 non-psittacine bird species housed at the Lincoln Park Zoo, finding that they spent more time in the area of their exhibit that was lit by the UVA light with birds from high light native ecological niches showing increased preference. The more comprehensive work on the broiler and laying hens (see [

16] for a review) demonstrates the importance of UVA and UVB lighting for the welfare and health of this species. In addition to the need to broaden and deepen research in this field generally, the impact of broad-spectrum lighting on behavioural management success has not been previously evaluated, and psittacids have also been poorly studied in this field in general.

Macaws must have access to an indoor area when kept in captivity in regions with temperate climates, as they dislike wind and are susceptible to frostbite [

17]. Behavioural management in the form of recall training should ideally be implemented with captive macaws, particularly with those housed in exhibits with an indoor and outdoor area. The ability to recall birds is important not only for day-to-day husbandry but also to ensure effective non-invasive health management of the birds. The success of behavioural management, such as recall training, is partly dependent on the environment in which it occurs, as negative stimuli from the environment will cancel out some or all of the impact of positive reinforcement for behaviour [

18]. It is therefore important for birds to feel comfortable when called indoors to remove any negative stimuli that could hinder the effectiveness of training. Moreover, enclosure usage is at least partly determined by the suitability of enclosure zones to the species in question, and areas of lower suitability may result in animals not fully using available space and resources [

19].

Given the sensitivity of the avian eye to light, we hypothesized that light levels in the indoor part of an aviary might impact the willingness of blue-throated macaws to remain in this part of their environment. We tested the impact of full-spectrum lighting installed in the indoor part of a macaw aviary on the latency to leave this area after being recalled in order to inform enclosure design and bird management moving forward.

2. Materials and Methods

We collected data on one bonded pair of blue-throated macaws, Zoological Information Management System Global Accession Numbers PYR12-00063 and ZRS15-08246, housed in our ‘MAC 1’ enclosure. This comprised of an indoor den area measuring approximately 327 cm length × 315 cm width × 243 cm height and an outdoor area measuring approximately 530 cm length × 320 cm width × 530 cm height—both with appropriate perching, food, and water provisions and linked with a remotely operated door and shutter. Prior to this study, the indoor light provision for these animals was comprised of one circular wall light approximately 35 cm in diameter containing one GE 2D butterfly CFL square double D 4 pin 16-watt lamp behind frosted glass, and a glass-panelled window measuring 78 cm width × 154 cm length, with glass approximately 9 cm thick, allowing some natural ambient daylight to penetrate the den. None of these light sources emitted any UVB or UVA light. Birds were recall trained through positive reinforcement prior to the study, such that they would enter the indoor den from outside in response to a bell, after which they were rewarded with food. Birds always had access to both in and outdoor parts of their aviary.

On the MAC1 indoor den ceiling, we installed a hydroponic light housing unit (Light Wave 4-tube 54W, Growth Technology, Taunton, UK) fitted with two High Output (HO) T5 fluorescent hydroponic lamps (Blue Growth Lights, Growth Technology, UK) and two 54W HOT5 fluorescent UVB-emitting lamps (D3+ 12% HOT%, Arcadia Reptile, UK). The lighting unit was meshed in with a cage of galvanized steel welded mesh with 2.5 cm apertures to prevent birds from tampering with the lighting. The lighting was calibrated to provide an ultraviolet index (UVI; Baines et al., 2016) of a maximum 2.0 at bird head height on the perch closest to the lamps. UVI was measured with a Solarmeter 6.5 UVI meter (Solartech, Greensboro, NC, USA). The lighting unit was installed but not used for several weeks prior to the beginning of the study, so it was present throughout.

We then conducted two series of experimental recall sessions, one in winter (November 2020) and one in the subsequent spring (March 2021). Both series consisted of twelve consecutive sessions with T5 lamps off and fifteen consecutive sessions with T5 lamps on, for a total of 54 sessions. Each treatment series was preceded by one week of unmonitored exposure to allow birds to habituate.

All sessions took place between 14:00 and 14:30 when the birds were not already inside the den. At each session, one keeper took a UVI reading using a Model 6.5 UV Index Solarmeter at the perching located directly under where the broad-spectrum light unit was mounted on the ceiling, at macaw head height, and a lux intensity reading at perch level using a RoHs Digital LUX meter MT30 model as well as a perching surface temperature using an infrared thermometer (Ketotek, Fujian, China). We also took a UVI and temperature reading on one of their outdoor perches (the same one each time) as well as an outdoor LUX reading immediately before or after the indoor reading.

After these parameters were collected, the keeper would conduct necessary husbandry indoors so that the birds were not disturbed after their recall. Both animals were then recalled into the den by the keeper. After the training concluded at each session, the keeper left their indoor enclosure via the keeper access door, and using two stopwatches, one for each animal, we viewed the birds through a gap in the keeper access door where we were hidden from view of the birds and recorded the time it took each individual bird to leave their indoor den to go back outside. The timing was capped at 900 s; if a bird had not left the den at this point, 900 was recorded as the duration.

Data were analysed using RStudio (Version 4.1.1). Data from both seasons were combined. To confirm the environmental effects of the lighting on the environment in the enclosure, Mann–Whitney tests (using the stats package in RStudio) were used to compare the effects of treatments on indoor and outside lux, UVi, and temperature. In order to determine whether the two birds could be treated as separate entities in analysis, we tested for autocorrelation between the birds using a Spearman’s Rank (again using the stats package in RStudio); this showed strong autocorrelation (Rs53 = 0.87, p (2-tailed) < 0.001). We, therefore, used mean data from the two animals in the analysis (i.e., for each trial, the mean duration spent inside by the birds was used).

We used the

shuffle function within the

Mosaic package [

20] to run a randomization analysis with 10,000 iterations in order to test for the effect of lighting on the duration spent inside after recall. Randomization is a valid strategy for analysing small- and single-n samples and is useful when working with small sample sizes in zoo contexts [

21,

22]. The residual between the means of each treatment is used as a test statistic, and the data are then shuffled randomly 10,000 times and a new test statistic calculated; the

p value is derived from the overlap of simulated test statistics with the observed test statistic.

4. Discussion

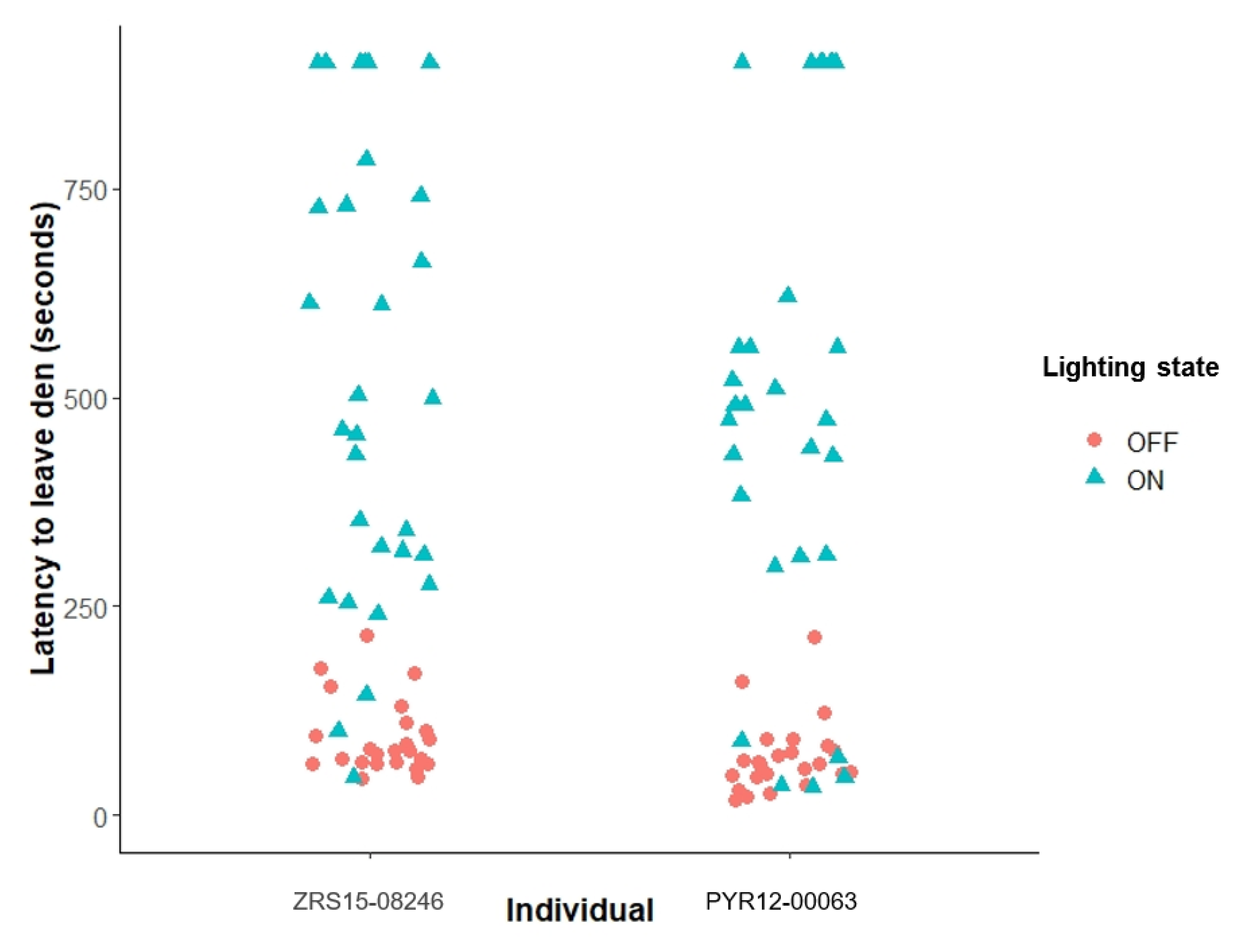

Our data show that the presence of the broad-spectrum lighting increased the time both animals spent in their inside den following each recall session. Improved vision due to the presence of UVA and overall higher colour rendering index (CRI) and lux with the additional lighting (all other measured environmental factors did not differ between treatments) may allow the birds to feel more secure or more visually comfortable in their environment, and therefore, more willing to remain inside after their training concluded. It is important to note that these birds are both parent-reared and a bonded pair and, therefore, exhibit less attachment to keepers compared with hand-reared birds.

These data are congruent with findings in other taxa [

13,

14,

15,

16] and could have wide applicability to other psittacid birds. The provision of broad-spectrum lighting in the captive environment could increase enclosure usage and improve behavioural management, as indoor training is more likely to be a success if the animals can see their environment more clearly and feel more confident navigating their indoor spaces. The birds’ overall welfare is likely improved with the additional broad-spectrum lighting inside because there is no longer a trade-off for the birds using the indoor space [

19]. Anecdotally, the macaws historically avoided spending time inside, even during cold weather, but after the installation of the broad-spectrum T5 lamps, this is no longer the case. The small overlap (

Figure 1) in latency to leave the den between with and without broad-spectrum lighting conditions reinforces the fact that birds did sometimes still choose to leave the den quickly in order to use outside resources and indicates that the birds were able to express a wider range of behavioural choice.

We do not know which parts of the UV spectrum were specifically important to the birds, so other types of lamps may prove to be just as effective. We had planned to conduct a UVB and UVA blocking study as part of our data gathering, which would have helped to inform us of this; however, all data collection had to cease as the birds started nesting and consequently reared three chicks. Further work could investigate this, as well as expand the data collection to other bird species, and include measures of enclosure and resource use. The inclusion of blood sampling or radiography could also indicate the impact of UV lighting on calcium metabolism and health [

11,

12]. However, based on the present small dataset and existing literature, we suggest that broad-spectrum lighting can facilitate the use of behavioural management in macaws, as well as impact other areas of health and welfare, which supports its use in indoor space for captive birds.