1. Introduction

LNG has been used as a marine propulsion fuel aboard LNG Carriers (LNGCs) since 1964, with further developments over the past decade, culminating in the introduction of the first LNG-powered carrier in 2000. Over the past decade, LNG has become a competitive fuel option, primarily due to stricter emissions regulations. These regulations favour LNG as a cleaner fuel, offering compliance advantages over traditional marine hydrocarbon fuels under MARPOL Annexe VI, despite its higher capital cost due to tank and fuel gas system requirements [

1].

In alignment with the IMO’s 2018 strategy, which targets a 40% reduction in CO

2 emissions by 2030 and 70% by 2050 (from 2008 levels), the adoption of LNG is accelerating. However, unresolved issues, such as methane slip and unburned hydrocarbon emissions, limit its long-term sustainability [

2].

The LNG maritime sector predicts growth in offshore LNG production, along with the rapid development of gas resources and rising demand for FLNG vessels. The swift expansion of equipment and processes in FLNG development addresses issues arising from carbon emissions, as well as weight and space constraints.

Current problems will focus on the fuel associated with existing hydrocarbon fuels and the incoming alternative fuel LNG in the marine sector. While LNG is promoted as a cleaner marine fuel for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, its effectiveness is debatable due to methane leakage during production, transport, and consumption [

3].

In other words, all other alternative marine fuels, such as natural gas, biofuels, alcohol fuels, and LNG, are unreliable energy sources due to their hydrocarbon content, as referred to in the Clean Energy Hypothesis. There will be many challenges to meet the clean energy criteria [

4].

The study proposes pathways for transitioning FLNG energy systems from LNG to zero-carbon fuels such as hydrogen, derived directly from LNG resources. Emphasis is placed on hydrogen–LNG co-firing gas turbine performance within an environment, linking Aspen HYSYS, MATLAB, and ANSYS Fluent.

Aspen Hysys thermodynamic modelling was used to evaluate pure LNG, blended LNGydrogen fuel, and pure hydrogen gas turbine models, highlighting trade-offs between efficiency and thermodynamic optimisation. Results show that co-firing with hydrogen (high specific energy) yields a distinct advantage over LNG for gas turbines used in FLNG power generation. To validate this concept, hydrogen gas turbines are examined in dual-fuel configurations, including the feasibility of applying complex processes in gas turbines for FLNG power systems [

5].

Gas turbine performance for a 50 MW unit was modelled in Aspen Hysys to focus on the process of 0–100% hydrogen blends. Parameters analysed included air–fuel ratio (AFR), Wobbe index, turbine inlet temperature, and other parameters, with a sensitivity analysis to quantify the effects of pressure ratio, equivalence ratio, as well as hydrogen fraction on efficiency, stability margins, and performance, which were validated with Gasturb software Version 15. The methodology bridges gas turbine performance to provide a transferable framework for fuel-flexible turbine optimisation for hydrogen blending, AFR calibration, and NOx reduction, aiming to mitigate the challenges of next-generation offshore turbines [

5].

5. Theory and Equations

5.1. Gas Turbine Technology

Gas turbine combustion cycles are based on the simple Brayton Cycle. The efficiency of the gas turbine is the ratio of the net output to the gross heat input, as shown below.

where

WTurbine = turbine work; WCompressor = compressor work; Wnet = net work

mf = fuel mass flow rate.; LHV = lower heating value of fuel

The heat input to the gas turbine is calculated by multiplying the fuel’s heat value by its mass flow rate.

Assume that fuel combustion within a period of one unit, t, sec, s, is used to calculate the power output of the gas turbine as

The above equation expresses the specific fuel mass flow of a gas turbine as a function of power output and thermal efficiency, given ambient conditions of 15 °C and 60% relative humidity [

26,

27].

5.2. Gas Turbine Pressure Ratio (PR)

The pressure ratio (PR) of the gas turbine is the most critical parameter for the thermodynamic efficiency and specific work output. However, a higher PR will increase the temperature rise across the turbine, generally leading to higher thermal efficiency, mechanical stress, and cooling demands. It is essential to perform a sensitivity analysis of the elevated best PR to ensure the turbine operates within safe thermal limits and achieves the target performance and energy output [

28].

To design the process cycle, there will be a separate portion for the equipment in the cycle, as shown below.

For the compressor, specify the inlet and outlet temperatures T1 and T2, respectively, and the compressor’s isentropic efficiency.

is used to compute the isentropic outlet temperature

T2S.

Use the isentropic relation (air,

γc ≈ 1.4) and pressure ratio for the compressor,

For the turbine, specify the inlet and outlet temperatures,

T3 and

T4, and the turbine isentropic efficiency,

ƞt, to compute the isentropic outlet temperature,

T4S.

Use the isentropic relation (hot gas,

γt ≈ 1.3–1.33), and pressure ratio for the turbine,

In the simple cycle, the overall cycle pressure ratio, PR, is set by the compressor PRc, and the turbine expansion ratio PRt is slightly lower due to combustor and diffuser pressure losses.

To obtain the optimum

PR for this case of 50 MW, it can be taken from the

PR sensitivity analysis graph and can also be calculated analytically to obtain the maximum specific work, such as

With the given turbine inlet temperature (TIT) and

γ ≈ 1.4 [

26].

5.3. Fuel Flow Calculation

Alternative ways to calculate the fuel flow rate for the required turbine output capacity are to, firstly, obtain the specific energy content of the fuel, such as the lower heating value (LHV) of each fuel, and the required thermal efficiency of the gas turbine:

The energy content of hydrogen, as its lower heating value (LHV), is approximately 0.34 MJ/kg, whereas LNG, primarily composed of methane (CH4), has an energy content of roughly 0.52 MJ/kg. The mass fuel flow rate for co-firing depends on the ratio of energy contributions from each fuel [

26].

5.4. Fuel Split Ration Calculation for Blending Fuel

It will depend on the percentage, which is determined by the volume percentage (~molecular percentage) at the mixer. If required to convert to mass fraction, multiply by the total fuel mass flow rate, using the molecular weights (hydrogen, MWH2, is 2.016 g/mol, and methane, MW

CH4, is 16.043 g/mol). There are different ways to split the fuel for a mixed ratio. If the design is based on the molar (volume) ratio, we must consider mass fraction and another factor for energy sharing, which will differ from the volume percentage-based approach as referred to in the

Appendix A [

26].

For mol-share, the mass fraction will be adjusted according to the volume ratio of the fuel blend for fuel species i and j.

where

= mole (or volume) fraction of species i

MWi = molecular weight of species i (kg/kmol);

MWj = molecular weight of species j (kg/kmol);

Wi = mass fraction.

The component mass flow for blending is as follows:

Energy share, which is considered the heat energy divided by the portion to be extracted from the respective fuel feed, is calculated as the total fuel with the LHVs of hydrogen (≈120 MJ/kg) and methane (≈50 MJ/kg), and the cycle efficiency ƞ, as in Equation (1). The equation for mass flow for the individual flow rate can be calculated by using the hydrogen fraction

:

The total mass flow rate is

5.5. Stoichiometric Air to Fuel Ratios

The optimal air-to-fuel ratio to achieve equal energy contributions will depend on the specific properties and energy content of the fuels, especially when co-firing hydrogen (H

2) and liquefied natural gas (LNG), as the primary component is methane (CH

4).

As per the equation, for every mole of methane, 2 moles of oxygen (or approximately 9.52 moles of air) are required for complete combustion, to convert this to a mass ratio.

The molecular weight of methane (CH

4) = 16.04 g/mol, and the molecular weight of air (approximately 78% nitrogen and 21% oxygen) is ≈28.97 g/mol (since the average molecular weight of air is close to this value). The mass of air required for stoichiometric combustion per unit mass of methane can be calculated as follows:

Thus, the stoichiometric fuel-to-air mass ratio for LNG (assuming it is primarily methane) is approximately 1:17.2.

The stoichiometric ratio for hydrogen fuel in a gas turbine is the ideal proportion of hydrogen and oxygen required for complete reaction, leaving no excess reactants. For hydrogen (H

2) combustion in air, the stoichiometric combustion reaction is as follows: two molecules of hydrogen gas react with one molecule of oxygen gas to produce two molecules of water vapour and release energy [

23,

26,

29,

30].

To calculate the stoichiometric AFR, use molecular weights: hydrogen (H

2) 2 g/mol and oxygen (O

2) 32 g/mol [

31].

The calculation for the air-to-fuel ratio (AFR) for the mixture for equal energy contribution is as follows:

Given the energy formula of the product of mass and lower heating value (LHV),

where

m is the mass flow rate, and

A is the air flow rate.

5.6. Wobbe Index for Co-Fire Gas Turbine

The Wobbe index is a critical parameter for assessing the interchangeability of fuel gases, including their performance in gas turbines. It is defined as the higher heating value (HHV) of the gas divided by the square root of its specific gravity (relative density).

For a gas turbine, especially in co-firing scenarios like hydrogen and liquefied natural gas (LNG), understanding the Wobbe index helps to ensure proper combustion and efficient operation, which requires higher heating values (HHVs) and specific gravity of fuel (SG), as per the following equation, to optimise the combustion process of mixed fuel characteristics.

For a co-fired turbine, the effective Wobbe index (WI_mix) is as follows:

By calculating the effective Wobbe index and adjusting turbine parameters accordingly, the turbine can maintain efficient operation and stable power output. However, the precise impact on power output will depend on the specific design and control capabilities of the gas turbine [

26,

32].

5.7. Equivalence Ratio (φ) and Excess Air Ratio (λ), as Well as Pressure Ratio (π)

Besides the fuel–air ratio, other ratios are essential in gas turbine thermodynamics and combustion analysis, such as the equivalence ratio (φ), excess air ratio (λ), and pressure ratio (π) for both single-fuel (non-blending) and multi-fuel blends, such as H2-LNG, in this research.

The equivalence ratio and excess air ratio equation are

Since .

(λ) = 1.0 stoichiometric; (λ) > 1.0 lean combustion (extra air); (λ) < 1.0 rich combustion.

For the actual air flow of the lean-premixed one,

In practical turbine operation, the turbine never operates at stoichiometric conditions; otherwise, the flame temperature would be too high, leading to thermal NOx emissions and material failure.

Instead, lean premixed combustion is used at a typical equivalence ratio of φ = 0.3–0.6, corresponding to an FAR of 30–60% of the stoichiometric value.

This keeps TIT (turbine inlet temperature) around 1350–1500 °C to align with material limits. For a hydrogen turbine, the stoichiometric FAR for H

2/air by mass is 0.029 (≈2.9%), and the typical turbine operating FAR is 0.009–0.018 (≈0.9–1.8%) under lean premixed conditions to reduce NOx and protect turbine materials [

26].

5.8. Equation for Stoichiometric Requirement per Mole of Blended Fuel

For a fuel blend of methane (CH

4) and hydrogen (H

2),

where

x is the molar fraction of H

2 in the blended fuel stream.

Therefore, the stoichiometric O

2 requirement per mole of blended fuel mixture is

This equation will provide the stoichiometric oxygen demand in mols of oxygen per mol of fuel mixture as a function of x.

When

x = 0, all methane

VO2,st = 2 and when

x = 1, all hydrogen

VO2,st = 0.5. As the hydrogen fraction increases, the oxygen requirement per mole of fuel drops because hydrogen needs less oxygen than methane [

26,

33,

34].

And stoichiometric moles of air are as follows:

The equation for stoichiometric AFR (mass basis) is as follows:

Regarding the excess air factor with equivalence ratio Equations (6)–(31) for 21% of oxygen in dry air, the molar flow rate will be

5.9. Fueling System to Gas Turbine Combustor

Current industrial research on fuel supply modes is most important for the development of hydrogen gas turbines: this includes diffusion, premixed, micro-mixed, and DLE (Dry Low Emission) for NOx reduction. In diffusion combustion, fuel and air are separately introduced into the combustor, and the flame forms at the interface where the mixing occurs. Turbulent diffusion leads to a thick flame front with high local temperatures. Diffusion flames are inherently stable and robust, making them extremely resistant to blow-off and flashback, even with highly reactive fuels such as hydrogen; however, their high adiabatic flame temperature results in substantial thermal NOx formation.

Fuel and air are pre-mixed before being injected into the combustor, generating a homogeneous lean mixture with an equivalence ratio ϕ ≈ 0.3–0.6. This significantly lowers flame temperature and reduces NOx formation. Premixed combustors produce shorter, more uniform flames and are widely used in low-emission turbine designs. However, hydrogen’s extremely high laminar flame speed increases the risk of upstream flame propagation (flashback) in premixed systems unless specially designed flame-holding and mixing elements are used. Therefore, although premixing is highly attractive for low-NOx hydrogen combustion, it may require an advanced injector to control real-time Lambda (λ).

For micro-mixing, it is built with multiple small-scale fuel injection ports to mix fuel and air extremely rapidly at the microscale before ignition, but without forming a fully premixed mixture upstream. This partially premixed approach allows hydrogen or fast-reacting blends to be handled safely, avoiding the high flashback risk of fully premixed systems. Micro-mixing burners limit residence time before ignition, restrict flame flashback pathways, and reduce local stoichiometric zones, lowering NOx. This strategy is now central to hydrogen-ready engines for hydrogen-LNG blends; micro-mixing provides an ideal balance between NOx reduction, stability, and safety. Advanced DLE (Dry Low Emission) is ongoing research to achieve lean premixing, dilution jets, and sufficient mixing time to manage high flame speeds and mitigate flashback, preventing hot spots and NOx spikes.

5.10. Hydrogen Fuel Combustion Correlation with NOx Emission

NOx formation in hydrogen-fueled gas turbines is a critical concern because hydrogen flames, although carbon-free, exhibit exceptionally high adiabatic flame temperatures and rapid reaction kinetics that strongly promote thermal NO formation through the extended Zeldovich mechanism. In lean-premixed hydrogen–air combustion, the high diffusivity of hydrogen and short chemical time scales result in steep temperature gradients and localised hot zones, where molecular nitrogen reacts with atomic oxygen to form NO, even in globally lean conditions [

35].

The rate of NO production is exponentially sensitive to the flame temperature and residence time in the high-temperature region, making the control of adiabatic flame temperature (Tad) and equivalence ratio (ϕ or λ) central to low-emission turbine operation. Unlike hydrocarbon fuels, hydrogen contains no fuel-bound nitrogen, so the prompt-NO and fuel-NO pathways are negligible. However, the dominance of thermal NOx at high flame speeds presents a challenge for maintaining ultra-lean, stable combustion without incurring flashback or excessive heat loss. Consequently, research on hydrogen turbines emphasises precise mixture control, staged combustion, and advanced cooling or dilution strategies to suppress NOx while sustaining flame stability and turbine efficiency.

There will be a base point for measuring the NOx index, and the surrogate’s qualitative Tadd adiabatic temperature, rather than a predictive ppm model to obtain the actual emission proxy. We can use the Zeldovich-type correlation, keyed to the adiabatic flame temperature calculator and heat loss assumptions, as per the equation [

35].

where

Eeff ≈ 75–80 kcal/mol:

β ≈ 2–3 (>0 leaner to lower NOx);

γ ≈ 0.5–1.0 (weak pressure effect for premixed flame;

C: calibrated from one to two known NOx data points.

5.11. Complexity for Molar Flow and Mass Flow

To meet the baseline power requirement, the stoichiometry per mole will vary, as hydrogen requires 0.5 mol of oxygen and methane requires 2 mol of oxygen. Even though hydrogen moles are higher, the demand for oxygen per hydrogen mole is lower, so the total air demand does not scale 1:1, which should be calculated as follows.

Energy per mole: LHVhydrogen ≈ 242 MJ/kmol and LHVmethane = 800 MJ/kmol; these deliver the same shaft power output, requiring 3.3 times more hydrogen than methane.

Energy per mass: LHV hydrogen ≈ 120 MJ/kgmol, LHV methane = 50 MJ/kgmol. For hydrogen, the energy per unit mass is higher than for methane, so the mass flow of hydrogen can be lower.

6. Simulation Analysis of Hydrogen Gas Turbine

Gas turbines are a primary power source for offshore floating platforms; all gas turbines are investigated and simulated using simple-cycle gas turbine flow diagrams. Compressors generate high-pressure air in the combustion chamber and further expand it through two-stage turbines, producing high- and low-pressure streams: high-pressure turbine (HPT) and low-pressure turbine (LPT) power output to link the FPSO power generator. Gas generators are controlled by the amount of fuel supplied to the compressor.

The chemical process software Aspen HYSYS (version 11) is used in conjunction with ANSYS simulation to predict and validate process-level performance in computational fluid dynamics (CFD). It is used to analyse the combustion flames of methane, hydrogen, and hydrogen-methane blended flames, and to compare them with other published analyses of flame stability. However, Ansys’s research findings are used in Aspen, and this article may not focus much on flame simulation. This article develops the transition towards low-carbon energy systems, which has brought natural methane (CH

4), hydrogen (H

2) and dual fuel for a simple of 50 MW class gas turbine that provides an optimal test rig case for investigating the operational impact of fuel flexibility and validates a dual-method simulation framework, Research methodology to consider for three scenarios are as follows: a gas turbine with single fuel LNG and hydrogen, and a gas turbine for the co-firing of LNG and hydrogen. To achieve 50 MW of electrical power, the approximate shaft power is 52.5–53.5 MW, depending on the generator efficiency [

7,

36].

The methodology enables a comprehensive evaluation of turbine efficiency, air–fuel ratios, exhaust conditions, flame stability, and emissions under various H2/CH4 mixing ratios. This is because hydrogen-rich fuel alters combustion dynamics, potentially leading to flashback and increased NOx formation, whereas methane-rich fuel emits CO2. Aspen HYSYS simulation provides thermodynamic balances for the 50 MW gas turbine, enabling calculation of the turbine inlet temperature (TIT), air–fuel ratios, and exhaust composition. Aspen HYSYS results to use in Matlab for sweep analysis and ANSYS Fluent CFD combustion simulation for fuel composition, AFR, and TIT target to resolve combustion chamber flow, flame structure, and emissions. For the coupling strategy, Aspen outputs serve as boundary conditions in ANSYS, and ANSYS results, including flame stability and NOx emissions, are used to validate the results in Matlab and adjust the Aspen assumptions.

6.1. Model for Pure LNG Fuel Gas Turbine

LNG turbine modelling in Aspen HYSYS involves simulating the performance of a gas turbine using LNG as fuel to support the design, optimisation, and operation of chemical reactions (

Figure 1). This is setup using the thermodynamics and physical properties of the components, utilising the Peng–Robinson equation of state.

The model, which includes a compressor, heat exchanger, and combustion chamber, is used in conjunction with a stoichiometric conversion reactor. This setup integrates all equipment, allowing for parameter adjustments to achieve realistic performance characteristics. Simulation results evaluate the turbine’s performance, including efficiency, power output, fuel consumption, and emissions.

6.2. Model for Pure Hydrogen Fuel Gas Turbine

Modelling a hydrogen turbine in Aspen HYSYS requires a detailed understanding of the system components, accurate estimation of thermodynamic properties, and careful integration of the combustion process. The simulation results can be used to optimise turbine performance and assess the feasibility of using hydrogen as a fuel in gas turbines.

Based on GT H2 100% simulation research, a hydrogen-rich fuel should be purified, which directly affects combustion stoichiometry, flame speed, and air–fuel ratio requirements (

Figure 2). Unlike LNG, hydrogen’s much lower molecular weight results in significantly lower volumetric energy density, meaning that for the same turbine output, a higher volumetric flow rate of fuel is required despite the relatively modest mass flow rate. This behaviour is confirmed in the material streams data, where the hydrogen mass flow needed to achieve the desired turbine heat input is substantially lower than that of an equivalent LNG feed. Still, the molar and volumetric flows are markedly higher. This highlights the challenge in designing injectors, piping, and combustors, as hydrogen’s diffusivity and velocity profiles must be carefully managed to maintain flame stability and prevent flashback.

The energy streams further confirm that, while the total heat input is sufficient to sustain 50 MW-class turbine operation, the energy distribution across the cycle differs from that with LNG firing. Hydrogen combustion releases heat more rapidly, thereby increasing the local flame temperature. Still, the turbine efficiency trends indicate that matching air supply, dilution, and pressure ratio is critical to prevent excessive NOₓ formation and turbine material stress. The turbine power output and compressor power balance show that, although net power generation is comparable to LNG scenarios, the margin between compressor work and turbine expansion is narrower due to the different heat-release and mass-flow characteristics of hydrogen.

This suggests that cycle optimisation, particularly in compressor pressure ratio, combustor cooling strategies, and turbine expansion staging, is essential for hydrogen-only operation. These findings are consistent with open-source research by Siemens and GE on hydrogen turbine trials, which validate that, while hydrogen enables carbon-free operation, its unique thermophysical properties necessitate significant adaptations to turbine design and operation.

6.3. Model for Hydrogen-Blended Methane Fuel Gas Turbine

Modelling hydrogen-blended methane fuel in a gas turbine requires careful consideration of both injection dynamics and combustion characteristics to ensure flame stability, efficiency, and emission control. In this model, the co-firing of hydrogen (H

2) and liquefied natural gas (LNG, predominantly methane) is achieved by integrating fuel injection into the gas turbine combustor (

Figure 3). The injection model defines premixed fuel streams, accounting for hydrogen’s distinct physical properties, including its high diffusivity, low density, and broader flammability range compared with methane.

To capture the mixing and combustion processes, the combustor geometry is discretised to simulate fuel-air mixing and ignition stabilisation under turbine-relevant pressure and temperature conditions. This article will focus more on the process and performance.

Firstly, research proposed a test rig in Aspen Hysys, a capacity-constrained rig that operates under control of the fuel molar flow within a range of 300–450 kmol/h. This envelope is suitable for injector sizing and fuel-train design based on current methane-fired turbine hardware, in accordance with current research practices for 50 MW power plants.

The second research pathway involves a performance–target comparison, aiming to maintain a fixed 50 MW net output across all blends and to evaluate the resulting requirements for fuel molar flow, air supply, and compressor work. Finally, the third angle of research explores the higher-efficiency cycle pathway. By considering recuperated or combined-cycle configurations, it becomes possible to reduce the fuel molar flow requirement per megawatt, easing the capacity gap for high-hydrogen blends.

Application of the air fuel ratio AFR for gas turbine combustion of blended fuel to be calculated using Equations (6)–(36) shows that molar AFR decreases when hydrogen fraction increases. In contrast, mass AFR increases because hydrogen has a very low molecular weight; consequently, combustion may need more air per unit mass of hydrogen.

These five research scenarios are referred to in

Table 1, which provides a clear parametric map for setting the equivalence ratio, dilution fraction, and π to maintain TIT, NOₓ, and net efficiency within the target while signalling where hardware or control adjustments are needed as the fuel transitions from LNG dominant to H

2 dominant. Key performance metrics include turbine efficiency, temperature distribution, and emission co-firing studies. This model establishes a baseline framework for evaluating the operational feasibility of hydrogen–methane blends in a 50 MW class gas turbine, providing a foundation for optimisation in terms of air–fuel ratio, injection velocity, and combustion chamber design.

6.4. Ansys Simulation for Combuster

For micro-mixing, it is built with multiple small-scale fuel injection ports to mix fuel and air extremely rapidly at the microscale before ignition, but without forming a fully premixed mixture upstream. This partially premixed approach allows hydrogen or fast-reacting blends to be handled safely, avoiding the high flashback risk of fully premixed systems. Micro-mixing burners limit residence time before ignition, restrict flame flashback pathways, and reduce local stoichiometric zones, lowering NOx. This strategy is now central to hydrogen-ready engines for hydrogen-LNG blends; micro-mixing provides an ideal balance between NOx reduction, stability, and safety.

Advanced DLE (Dry Low Emission) is ongoing research to achieve lean premixing, dilution jets, and sufficient mixing time to manage high flame speeds and mitigate flashback, preventing hot spots and NOx spikes. To avoid unnecessary computational complexity, the k–ε RANS (Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes) model is used to obtain velocity, accurate pressure drops, temperature distribution, and mass-flow behaviour, required to validate the combustion process with the average flow by introducing two transport equations by using two variables: the turbulent kinetic energy (k), which quantifies turbulent energy, and its dissipation rate (ε).

To ensure computational efficiency, a simplified steady RANS simulation using the Reliable k–ε turbulence model is utilised, along with an Aspen HYSYS gas turbine model with global steady-state equations to investigate combustion thermodynamics, predict the combustor exit temperature (T4), and perform full-cycle integration with the gas turbine model. This model is popular for its numerical stability, but it has some limitations, such as poor performance near stagnation points and minimum predictions of turbulent kinetic energy under certain conditions. RANS provides stable convergence for hydrogen and LNG mixtures while resolving the dominant flow structures needed to predict flame anchoring, mixing, and T4 distribution.

CFD is used to analyse HYSYS data without the need for a detailed combustor model, where flame structure and mixing behaviour are important. Therefore, LES (Large Eddy Simulation) and URANS (Unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes) may not be used to avoid the time and cost without adding value relevant to thermodynamic validation or cycle modelling [

37].

6.5. Hydrogen Flame Simulation

Hydrogen flame speed is about 250~300 cm/s compared with hydrocarbon gasoline, about 50 cm/s, which means that it is five to six times faster than conventional hydrocarbon fuel. This is important because a fast flame speed offers several advantages, including complete combustion. Also, hydrogen has the highest specific energy of any gas. During ignition, hydrogen can lead to very high diffusivity and alter flame behaviour. Hydrogen has a high theoretical research octane number (RON) of approximately 130 or higher, but its tendency to auto-ignite complicates its use.

All these impacts mean that a gas turbine requires three times higher flow rates for the same power output and necessitates adjustments to the fuel accessory system. It has been found that hydrogen is not preferable for pre-ignition, which requires limited operation conditions for lean combustion. Flashback studies of hydrogen-enriched methane-air flames at a constant fuel–air ratio, as hydrogen enrichment can cause flashback. The further development of the proven solution across different burner designs is a promising approach for improving flame stability.

The research work presented above is on the simple flame combustor, conducted using CFD analysis, with a progress-variable image corresponding to an instantaneous snapshot of the flame for visualisation of combustion velocity: mass fraction of hydrogen, mass fraction of oxygen, total temperature of the combustor, and analysis for turbulence flow (

Figure 4). Here, the research will not provide a deeper discussion for flame analysis, only a superficial focus on the reaction zone, such as the distortion effect of the Eddy phenomenon, the unburnt gas region and the burnt gas region, as well as achievable results from hydrogen feeding from the process flow to the gas turbine.

7. Sensitivity Analysis

7.1. Overview of Constraint Fuel Flow Simulation for 50 MW Gas Turbine

Standard research practices typically involve changing either the shaft output power, turbine inlet conditions, equivalence ratio, or heat input and then calculating the outputs accordingly. Simple cycle efficiency calculations numerically for the band (ƞ ≈ 0.35–0.41), using equation in

Section 5.5, would deliver a power output of ≈38.11 MW at a hydrogen fraction of 0%, 30.13 MW at 30%, 24.8 MW at 50%, 19.48 MW at 70%, and 11.5 MW only at 100%, as referred to in

Table 2. However, it could help isolate and test the effects of kinetic and mixing. Another factor to be adjusted to achieve the steady 50 MW is efficiency and LHV.

In this hydrogen gas turbine research, more emphasis is placed on the hardware capacity of the considered fuel train and injector limit rather than on the fairness criterion. This approach is clearly distinct from the constant–power comparison used to determine which hydrogen fraction performs best, intending to achieve 50 MW. A research comparison of H

2 blending, using the method of constraining the fuel molar flow, which is a critical view of the research proposal (fuel molar flow 300–450 kmol/h for “fair comparison”), based on analysis from the current research published data, can be observed in the following

Table 2.

Despite the LHV per mole differing by blend, fixing the fuel molar flow to 300–450 kmol/h is a crucial way to compare blending scenario; it may yield inconsistent power results due to varying heat input as it allows for a more consistent comparison of thermal input and achievable power 50 MW across the blending process, especially after the test rig result showed that the 0–70% blending scenario is achievable for 50 MW with constraint fuel molar flow. However, 100% pure hydrogen, which fuels motor flow, widely swings, as shown in the table and plotted graph.

For aiming the net power of 50 MW without a fuel molar flow constraint, the calculation result obtained using equations in

Section 5.5 is as follows: 591 kmol/h (0% H

2), 747 kmol/h (30%), 907 kmol/h (50%), 1155 kmol/h (70%), and 1958 kmol/h (100%). None of the hydrogen fraction results fall within the proposed 300–450 kmol/h window, so the constraint hard-limits output at 50 MW; especially, this may require a higher hydrogen flow, as per the simple cycle calculation. For the trial of hydrogen molar flow to decrease within the range of 300–450 kmol/hr to obtain 50 MW by 100% pure hydrogen, it may need the efficiency to achieve (ƞ = 165%), which is impossible and is only achievable only when net power is 7–11.5 MW—refer to

Table 3 and that is perfectly fine for a combustor rig, but it may not meet 50 MW; the only way of adjusting the required fuel flow is to achieve 50 MW for each hydrogen fraction.

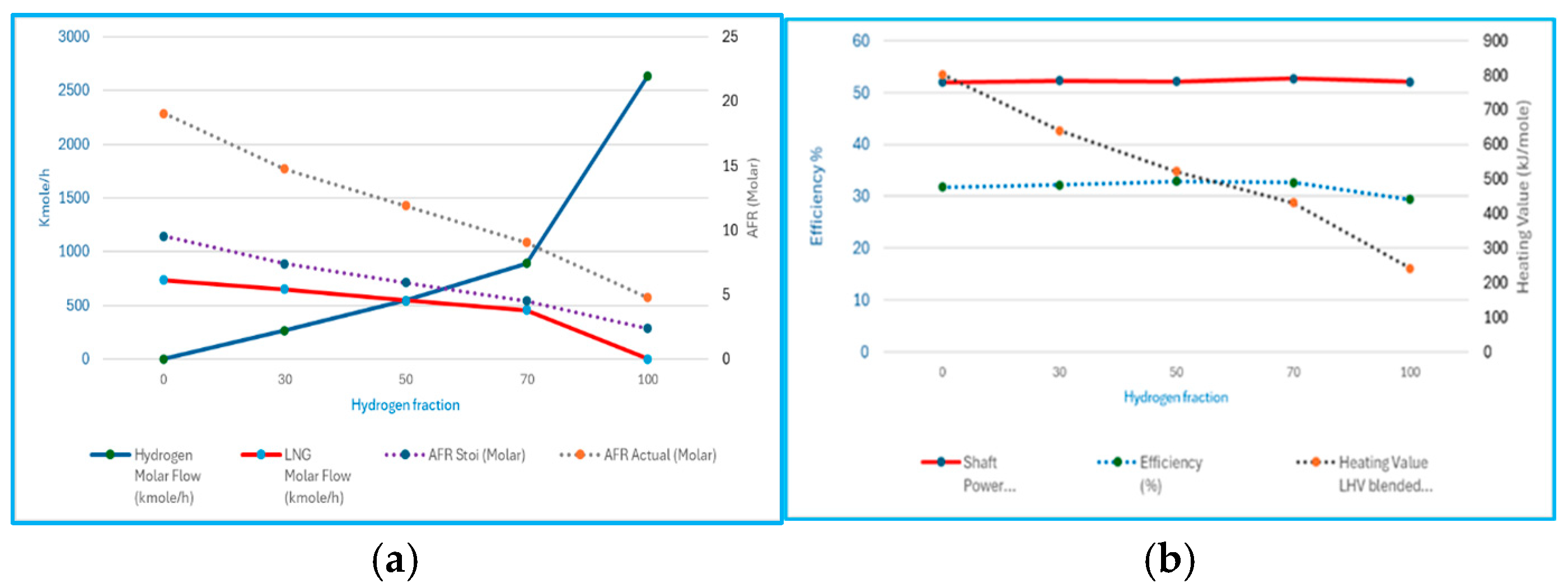

For this test rig, constrain the fuel flow rate at 420 kgmol/h, fixed for a 100% fuel-to-air ratio, to calculate the hydrogen fraction until it increases to 100% to monitor the changes in flow rate for the power achievable of the shaft power, as shown in

Figure 5 and

Table 3. A key finding is that the air flow rate decreases since the hydrogen flow increases to 100%, and the excess air ratio λ is 2 for this case to complete the combustion. This central constraint affects the system, causing it to become progressively more air-lean relative to the actual mixed-fuel feed as the hydrogen fraction increases. Power results follow the same logic with air sized for the 420 kgmol/h basis. However, the decline in this power trend across the 50 MW reference line at a hydrogen fraction of 30% indicates that the blending ratio is most effective in achieving the 50 MW power target.

Firstly, the strength of the idea view, with a fuel flow rate of 300–450 kmol/h, does cover the operating window for 0–70%. It removes the extreme 100% pure hydrogen case, which is out of both boundaries of the fuel molar flow (~1952 kmol/h) and in the compressor demand (~217 MW)—refer to

Table 3, showing that 100% pure hydrogen needs redesigned injectors and compressors, allowing fuel flow float to keep the constant power at 50 MW in comparison. This makes sense if the research focuses on the comparative performance of blends under a standard injector/fuel train sizing constraint. It has been demonstrated that 100% pure hydrogen necessitates redesigning injectors and compressors to maintain a constant power of 50 MW, as fuel flow fluctuates.

According to simulation results, a molar flow capacity-constrained test rig can provide valuable data on combustion, stability, and emissions across blends; however, it cannot accurately represent a full-load hydrogen operation without substantial hardware expansion. Excluding 100% hydrogen from the fair set means that pure hydrogen requires a step-change in fuel flow and air system sizing. Even hydrogen within the 30–70% limitation range has a lower bound that is very tight compared to rich methane blends. The research option is to study the 0% hydrogen as a pure LNG case, with 30–70% blending of the hydrogen and LNG case, as well as the 100% pure hydrogen case of a gas turbine.

7.2. Overview of Locked-Combustor State Simulation

Locking the combustor state in gas turbine testing is a critical procedure for validating and certifying combustor performance, especially for new fuels such as blended and pure hydrogen. Key combustor parameters are fixed to study the specific phenomena. In simple terms, to establish the thermodynamic and fluid dynamic conditions at the combustor inlet during the test, one needs to achieve a stable and repeatable baseline from which the impact of a single variable can be measured, such as fuel composition. The combustor’s locked state is crucial for hydrogen validation, enabling comparisons between scenarios. If testing is conducted without a locked state, the combustor inlet temperature (T3) and pressure (P3) will differ, impacting the accuracy of the comparison and the validity of the research data.

In the lock combustor simulation, the analysis is structured to hold the combustor state fixed, defined by inlet pressure to around 40 bar and temperature 407 °C, pressure drop Δp/p, primary-zone equivalence ratio ϕ, and turbine inlet temperature within an acceptable range for all five scenarios, while allowing fuel flow to vary freely across blends of hydrogen and methane to achieve 50 MW of net power with an efficiency of ƞ = 0.38, with an excess fuel ratio Lambda of λ = 2.

This framework reflects the physical reality for maintaining a stable combustor exit condition and meeting the turbine’s thermal demand; the system must supply as much fuel as the chemistry requires, regardless of the volumetric or molar rate. By removing artificial constraints on the fuel molar flow, the lock combustor simulation highlights the actual differences in hydrogen and methane energy densities and stoichiometry, enabling a fairer comparison of efficiency, air requirements, and compressor work across the hydrogen 0%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100% cases, as per specific metrics calculated by the equation shown in

Section 5.

The results across the five scenarios show in

Table 4 that while a methane-rich operation (0% H

2) has a higher fuel mass flow, it delivers energy more efficiently on a molar basis due to methane’s higher LHV. As the hydrogen fraction increases, the necessary molar fuel flow rises significantly, with 100% H

2 demanding nearly three to four times more molar flow than pure methane to sustain the same thermal output. However, this higher molar demand is offset by hydrogen’s very low molecular weight, so the overall fuel mass flow rate remains modest compared to LNG.

The lock combustor state simulations, without constraining fuel flow, provide a direct view of how hydrogen blending influences gas turbine cycle performance. performance as shown in

Figure 6. At 0% H

2 (pure LNG), the model indicates an air molar flow of ~13,965 kmol/h, with ~735 kmol/h of fuel, yielding a net power of ~52 MW. As the hydrogen fraction increases, both the air and fuel molar flows progressively reduce, falling to ~13,505/650 kmol/h at 30% H

2, ~13,018.6/547 kmol/h at 50% H

2, and ~12,167/456 kmol/h at 70% H

2, while keeping shaft power at ~52 MW; also, hydrogen molar flow is more extreme, with an increase to 2635 kgmole/h, with ~12,542 kmol/h of air and no reported achievment of a net power target. These results highlight the impact of hydrogen’s lower molar heating value: a higher molar flow is required to maintain stoichiometry at a constant combustor state; however, the overall thermal energy release is still necessary to meet turbine power requirements. Additionally, it is demonstrated that hydrogen at 30% is the optimal point to achieve 50 MW across the blended fuel range of 30% to 70%, as shown in the reference line in

Figure 5.

Examining the gas turbine work balance further emphasises the trend. At 0% H2, the heating value is at its maximum because LNG is used to meet the shaft power demand of approximately 52 MW, consistent with the highest net output case. As the hydrogen content increases, the heating value decreases steadily: 639 kJ/mole at 30% H2, ~522/52.13 MW at 50% H2, ~431/52.73 MW at 70% H2, and ~241.8/52.05 MW at 100% H2. This reduction aligns with the lower overall mass throughput at higher hydrogen fractions, since each mole of hydrogen is much lighter (2 g/mole) on a molar basis. So, per molecule, LNG releases three times as much energy as hydrogen when combusted. Hence, blending fuel shifts from rich methane to rich hydrogen, and the average heating value per mole of blended fuel decreases sharply, despite a reduction in the effective cycle efficiency as the H2 fraction rises.

This highlights a key research trade-off: hydrogen simplifies molar supply requirements, but its low energy per mole limits the achievable power unless the system design is adjusted. To better understand the analysis of re-expressing the hydrogen flow on a mass basis (MJ/kg), the expected trend shows that mass-based LHV rises, even though molar-based LHV falls within the target of ~52 MW per (

Table 5).

Taken together, these unconstrained fuel flow results suggest that a lock combustor model provides critical insights into the natural behaviour of hydrogen–methane blends before applying hardware constraints. The decreasing air and fuel molar requirements with increasing hydrogen fraction highlight the potential for smaller air systems and lower compressor loads in hydrogen-rich operation; however, the associated loss of net power underscores the need to redesign the cycle.

This research establishes a benchmark: unconstrained hydrogen blends can achieve only ~59% of methane’s net power under the same combustor conditions. Thus, moving from LNG to high-H2 or pure hydrogen operation requires either increased fuel flow capacity, higher turbine inlet temperatures, or efficiency-enhancing cycle modifications (e.g., recuperation). The lock combustor state simulations, therefore, frame the engineering challenge: balancing the reduced carbon emissions of hydrogen with the need for new design measures to maintain turbine output.

7.3. Overview of Pure Hydrogen Gas Turbine Simulation

According to the above simulation, 100% pure hydrogen requires a separate category, distinct from hydrogen and LNG blending, which involves a 30%-hydrogen-to-70%-hydrogen ratio. As shown in

Figure 7, a pure hydrogen gas turbine simulation was carried out with the condition of a non-constrained flow and lock combustor, and adjusted to 50 MW; the base operating point of hydrogen fuel flow H

2 ≈ 2550 kgmol/h and air ≈ 12,138 kgmol/h, which corresponds to λ ≈ 2.0 on a stoichiometric molar basis for hydrogen AFR (stoichiometric) ≈ 2.38 mol air per mol H

2.

A large amount of molar flow of hydrogen is a direct consequence of its lower LHV per mole relative to methane to meet the same heat input; a hydrogen-fired turbine, therefore, requires roughly 3.3× more moles of fuel than a methane-fired one. On a mass basis, however, the hydrogen flow is modest at 2550 kmol/s, corresponding to approximately 1.428 kg/s, indicating that even a large molar flow can be relatively small in terms of mass flow. At this base point, the thermal input for the locked setting produces 50 MW (consistent with a conservative simple-cycle assumption and the specific compressor/expander balances embedded in this case).

The research findings of a pure hydrogen gas turbine with a lock combustor and a non-constraint simulation case reveal the distinct thermodynamic behaviour of the gas turbine. For the fixed-hydrogen flow case, increasing the excess-air ratio from lean-rich (λ ≈ 1.6) to very lean (λ ≈ 2.4) results in a proportional rise in air molar flow, increasing the compressor work and slightly reducing both net and shaft power, while NOx decreases sharply due to a cooler adiabatic flame temperature under leaner operation. Conversely, when λ is fixed (≈2.0) and hydrogen flow varies, the net and shaft powers are almost linearly related to the total heat input, confirming that fuel flow rate governs power at a constant mixture ratio.

The NOx index remains nearly constant since combustion temperature does not change significantly with fixed lambda. These trends confirm that hydrogen’s high reactivity and low molecular weight drive strong sensitivity to lambda (mixture leanness), rather than to flow rate itself. To emphasise the effectiveness of power output, lean-premixed lambda control is the most effective lever for the pure hydrogen case.

7.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Gas Turbine Constrainted Fuel Flow

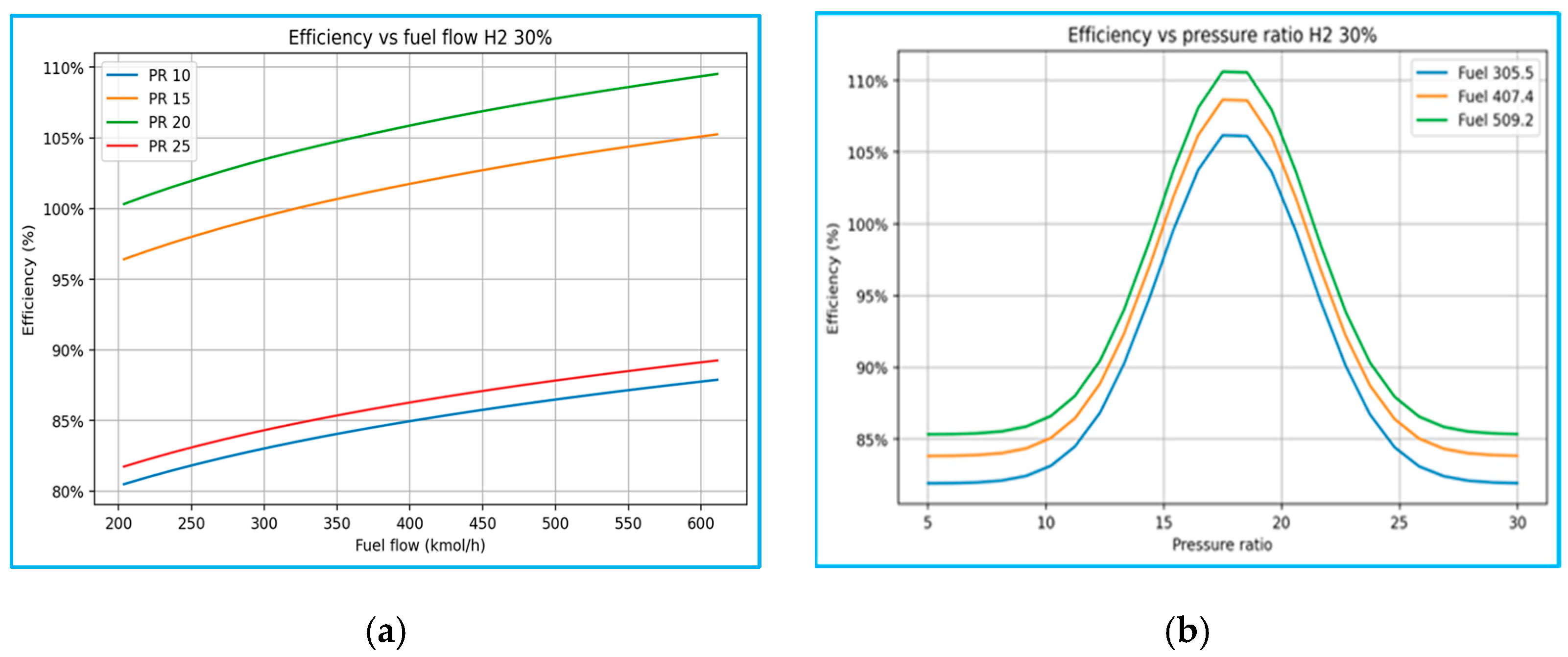

The sensitivity analysis conducted in this study assesses the variation in cycle efficiency with respect to two critical operational parameters: the fuel flow rate and the turbine pressure ratio (PR). The combustion chamber pressure ratio in a gas turbine is primarily determined by the compressor pressure ratio rather than the fuel type. However, different fuels can affect combustion temperature, flame speed, and pressure losses, thereby indirectly affecting the pressure ratio. As shown in

Table 6, the typical compressor pressure ratio ranges from 10:1 to 30:1, depending on the turbine design (aero-derivative or heavy-duty). The pressure at the combustion chamber inlet is thus significantly influenced by this compression ratio. While the compressor dictates the overall pressure ratio, the type of fuel impacts the combustion process, pressure losses, and combustion stability. LNG and H

2 pressure ratios are compared as follows.

In this research, five blending scenarios were considered, representing hydrogen mole fractions of 0%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100%. As shown in

Figure 8, all results were recorded. From the results of five scenarios with H

2 at 30% and CH

4 at 70%, data were plotted as three-dimensional (3D) graphs of efficiency versus mixed-fuel flow, and PR was also plotted. These graphs were then supported by two-dimensional (2D) cuts along fixed operating conditions. These visualisations provide a comprehensive map of the turbine’s performance envelope across varying compositions, enabling direct comparison of fuel blends and identification of operational bands associated with maximum efficiency.

The above 2D sensitivity analyses, in which one parameter was fixed while the other was varied, provide additional clarity. Efficiency versus fuel flow plots demonstrate that hydrogen-enriched fuels diverge significantly from pure LNG behaviour, particularly at elevated PR values. Efficiency versus PR plots reveal that stable, high performance under hydrogen-rich conditions is achievable only within narrow PR bands, underscoring the importance of precise integration between compressor and turbine design.

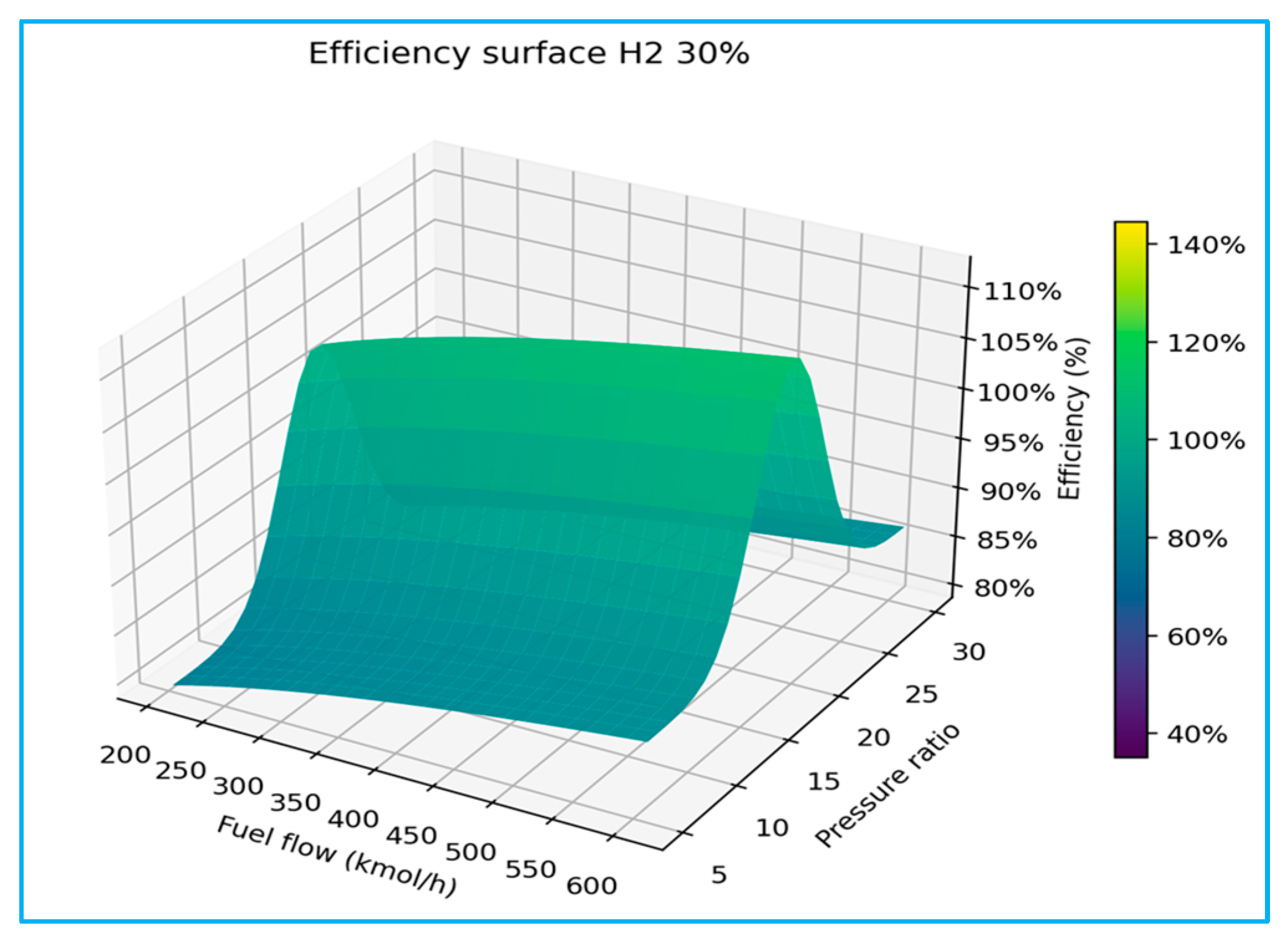

As shown in

Figure 9, the above 3D plots confirm a common trend across all cases: efficiency increases with pressure ratio up to an optimum value (typically 16–20), beyond which further increases result in a decline. Similarly, higher fuel flow rates contribute to increased net power but yield diminishing efficiency gains due to elevated compressor work and associated thermal penalties. To demonstrate the broad efficiency stability over a wide range of PR is to reflect combustion characteristics. In contrast, distinct differences emerge between the blending cases of pure LNG (0% H

2) and 100% H

2, which exhibit sharp sensitivity to PR variations, with efficiency strongly dependent on the tight matching of the compressor and turbine. Among the five scenarios, the intermediate blends (30% H

2 and 70% CH

4) exhibit hybrid behaviour, with performance trends that interpolate between the volumetric stability of LNG and the high reactivity of hydrogen.

These findings suggest that turbines optimised for LNG cannot be directly transitioned to high-hydrogen operation without significant adaptation of operational control strategies. The sensitivity analysis results collectively address the challenges and opportunities of hydrogen integration in gas turbine systems by reviewing the baseline model simulation.

7.5. Sensitivity Analysis of the Pure Hydrogen (Non-Blending) Simulation

Sensitivity analysis is a critical process in the gas turbine simulation workflow, enabling the determination of how varying input parameters can apportion uncertainty in model output. This process identifies which parameters exert the most significant influence on the system’s performance, thereby prioritising more precise measurements to control operations and achieve better performance. Systematically varying a single parameter in a gas turbine simulation is called a sweep. The most robust approach is to conduct a more robust sensitivity analysis; a multi-parameter sweep is conducted across lambda, fuel flow, and compressor load, as shown in the

Table 7.

For pure hydrogen gas turbine operations running with lean-premixed (Lambda λ ≈ 2), the sweep colour mapping graphs indicate that Lambda λ is approximately 2 in the central region, which controls the adiabatic flame temperature. This mitigates thermal NO formation while retaining flame stability and avoiding flashback. Additionally, the chosen Lambda λ = 2 increases the total molar throughput of reactants, modestly increasing compressor work and slightly reducing net power compared to the same fuel flow at a lower λ.

Referring to

Figure 10, the two-dimensional colour map of Lambda λ versus hydrogen levels, along with efficiency and power metrics, reveal key changes within the Lambda λ ≈ 1.6–2.4 and hydrogen flow 0.7–1.3 range, showing consistent patterns in the colour-coded flow. Firstly, net power increases with hydrogen flow. However, increasing Lambda λ reduces the net power due to the compressor penalty, requiring more air intake to be compressed, causing the constant-power contours to tilt upward with λ. Secondly, when λ is 1.6 to 2.0–2.2, and beyond this point, if fuel flows around 0.95–1.1 times the base, extra air does not help, and the compressor work begins to reduce efficiency.

When examining NOx in colour mapping of Lambda λ against hydrogen flow, in

Figure 10c, the NOx index drops steeply with increasing λ. It remains relatively unaffected by minor fuel-flow variations at a fixed Lambda λ, which illustrates that a practical window of NOx index is considerably lowered where η stays near its peak while Lambda λ ≈ 2.1, with hydrogen flow close to the baseline. This represents the classic trade-off in hydrogen operation: deploying leaner mixtures to cut NOx results in a higher compressor load, which raises the combustor’s adiabatic temperature and increases the associated risk.

For the pure hydrogen locked-combustor configuration targeting 50 MW, the maps support the implications of an operating-window set-point selection around λ ≈ 2.0–2.2, with hydrogen as the base fuel (minor fuel trims as needed to achieve 50 MW exactly). Referring to

Figure 11, this selection balances the low NOx propensity with compressor-work penalties and stability margins. If emissions constraints tighten, nudging Lambda λ ≈ 2.2 offers a marked reduction in the NOx index with only a minor efficiency trade-off. If power headroom is a priority, modestly raising the base while holding λ near 2.0 increases net power with a contained NOx impact.

The simulation results were imported into MATLAB to generate a visual normalisation in the form of a heat map, displaying the NOx index, Tadd, efficiency, and net power (MW), with contour colour gradients to visualise how each property changes with the excess ratio lambda λ and hydrogen molar flow rate. The NOx field is normalised to the reference case (Lambda λ ≈ 2.0, H2 ≈ base 2330 kgmol/h), where the normalised value of colour is ≈1.0. If the normalised value colour is greater than 1.0 (warmer: orange to red), it represents a higher NOx propensity, associated with a richer mixture (lower λ) and a hotter flame zone. If colour is less than ≈1.0, indicate the lower NOx formation, corresponding to leaner mixtures (higher Lambda λ) with lower adiabatic flame temperature.

The adiabatic flame temperature Tadd map typically uses a yellow–red scale increasing with temperature (hotter zones at lower λ), moving rightward (toward leaner λ) as the excess-air ratio (λ) increases from 1.6 to 2.4 and as the constant fuel flow cools; the map confirms that the thermal dilution decreases from approximately 2450 K to 2100 K, driven by enhanced air dilution and heat capacity loading. This temperature reduction sharply lowers the NOx index by nearly 70–80% across the lean range, as predicted by the exponential temperature sensitivity in the Zeldovich thermal–NO mechanism, as described in Equation (39). However, the same dilution increases compressor work, which slightly reduces net and shaft power.

The efficiency map displays light-green/yellow zones, indicating an optimal ridge near λ ≈ 2.0–2.2, where combustion completeness and completed load are balanced. The net power map is dominated by fuel flow, with darker blues indicating lower hydrogen feed and warmer colours (orange to red) indicating higher hydrogen flow. Consequently, the efficiency map shows a ridge between Lambda λ ≈ 2.0 and 2.2, beyond which the efficiency declines despite continued NOx improvement, suggesting that excessively lean mixtures lead to performance penalties without substantial emission gains.

At a fixed λ = 2.0, sweeping the hydrogen molar flow rate between 0.7× and 1.3× the base value (2550 kgmol/h) reveals a near-linear relationship with the net power output, which increases from ≈ approximately 35 MW to 65 MW. The adiabatic flame temperature varies modestly (±2–3%) since the air/fuel ratio remains constant, keeping the NOx index nearly flat across this sweep. The efficiency peaks slightly below the nominal design fuel rate (approximately 0.95 times the base), where turbine expansion and compressor load are most balanced. Combining both trends identifies an optimum operation window at λ = 2.0–2.2 and H2 ≈ 2400–2600 kgmol/h, where ηₗₕᵥ exceeds 40%, the NOx index is minimised by ~70%, and the net power target of 50 MW is maintained. These findings confirm that lean-premixed operation offers the best compromise between efficiency, power, and low-NOx performance for 100% hydrogen gas turbine combustion.

In summary, warmer colours (red/orange) indicate a higher flame temperature and higher power, but also higher NOx. Cool colours (blue/green) indicate a leaner operation, lower flame temperature, and reduced NOx, but at the expense of power and efficiency.

9. Conclusions

The comparative evaluation of hydrogen and methane fuel flows reveals different requirements between molar and mass flow rates, with direct implications for turbine operation and air management. On a molar basis, the same 50 MW thermal duty requires approximately three times as many moles of hydrogen as methane, because hydrogen’s lower molar heating value (approximately 242 MJ/kgmol) is only one-third that of methane’s (approximately 800 MJ/kgmol). Conversely, on a mass basis, hydrogen flow is lower due to its exceptionally high specific heat of combustion (≈120 MJ/kg versus ≈50 MJ/kg for methane).

This divergence means that while hydrogen appears to have higher molar throughput, it increases volumetric flow through the combustor, reducing air–fuel mixing. Furthermore, the stoichiometric oxygen requirement per mole is lower for hydrogen (0.5 mol O2/mol H2) than for methane (2.0 mol O2/mol CH4), so the total air requirement does not scale linearly with molar flow rate. Consequently, hydrogen combustion generally operates with higher apparent excess air ratios at the same thermal power, thereby enhancing flame stability and reducing peak flame temperature. However, it also requires tighter control of the equivalence ratio to mitigate flashback and NOx formation.

This non-constrained lock combustor framework is highly relevant for research because it removes arbitrary hardware limitations and exposes the fundamental thermodynamic trade-offs associated with hydrogen blending. It enables the clear identification of operating hydrogen, providing benefits such as faster flame speed, reduced CO2 emissions, higher volumetric fuel flow demand, and tighter compressor/airflow margins. By simulating the full range from 0% to 100% H2 under constant combustor states, the model provides a baseline reference for experimental test rigs and OEM designs, showing what the turbine could achieve if unconstrained by injector or manifold capacities. This duality between the “ideal non-constrained case” and the “capacity-constrained rig case” provides a comprehensive methodological model for developing hydrogen-ready gas turbines.

The pure hydrogen gas turbine simulation under locked-combustor, non-constrained flow conditions serves as the fundamental baseline for evaluating hydrogen’s combustion and performance behaviour in advanced gas turbine systems. In this configuration, the combustor inlet pressure, temperature, and pressure drop ratio (Δp/p) are fixed to reflect realistic aerothermal conditions. At the same time, the air and fuel flows are allowed to vary freely to satisfy the target net power output of 50 MW. This setup isolates the intrinsic thermodynamic behaviour of hydrogen, eliminating external flow limitations, and reveals the direct influence of stoichiometry (Lambda λ) and heat release on turbine performance, efficiency, and emission trends.

The results demonstrate that, unlike methane-fired operation, pure hydrogen combustion requires a significantly higher molar fuel flow rate, typically about three times greater, to supply the same thermal input because of hydrogen’s lower molar heating value (≈242 MJ kmol−1 compared with 800 MJ kmol−1 for CH4). However, on a mass basis, the fuel requirement remains comparatively small due to hydrogen’s low molecular weight. At the locked-combustor state (λ ≈ 2.0), the system achieves an adiabatic flame temperature around 2300–2400 K, supporting complete combustion and stable ignition with minimal carbon-based emissions. The absence of carbon eliminates CO2 and CO formation, focusing all emission concerns on thermal NOₓ.

Parametric sweeps of Lambda λ and hydrogen molar flow show a clear trade-off between power, efficiency, and NOₓ formation. Leaner mixtures (Lambda λ > 2.0) substantially reduce the flame temperature and NOₓ index (by up to 70–80%), though at the cost of reduced thermal efficiency and turbine power due to increased compressor load. Conversely, operating near Lambda λ ≈ 1.8–2.0 achieves the optimal balance, where ηₗₕᵥ ranges from 40 to 42% and the net power output remains near 50 MW. These findings confirm that lean-premixed hydrogen combustion under non-constrained flow conditions delivers both high specific power and low emissions, validating hydrogen’s viability as a clean turbine fuel when supported by advanced mixing and thermal management strategies.

In summary, the locked-combustor, non-constrained hydrogen case establishes high reactivity, elevated flame temperatures, and intense sensitivity to air–fuel ratio, all of which characterise the fundamental behaviour of a zero-carbon gas turbine cycle. The analysis highlights the critical role of λ-control in optimising efficiency and NOₓ performance and provides a validated framework for subsequent constrained-flow and hybrid-fuel (H2–LNG) simulations.

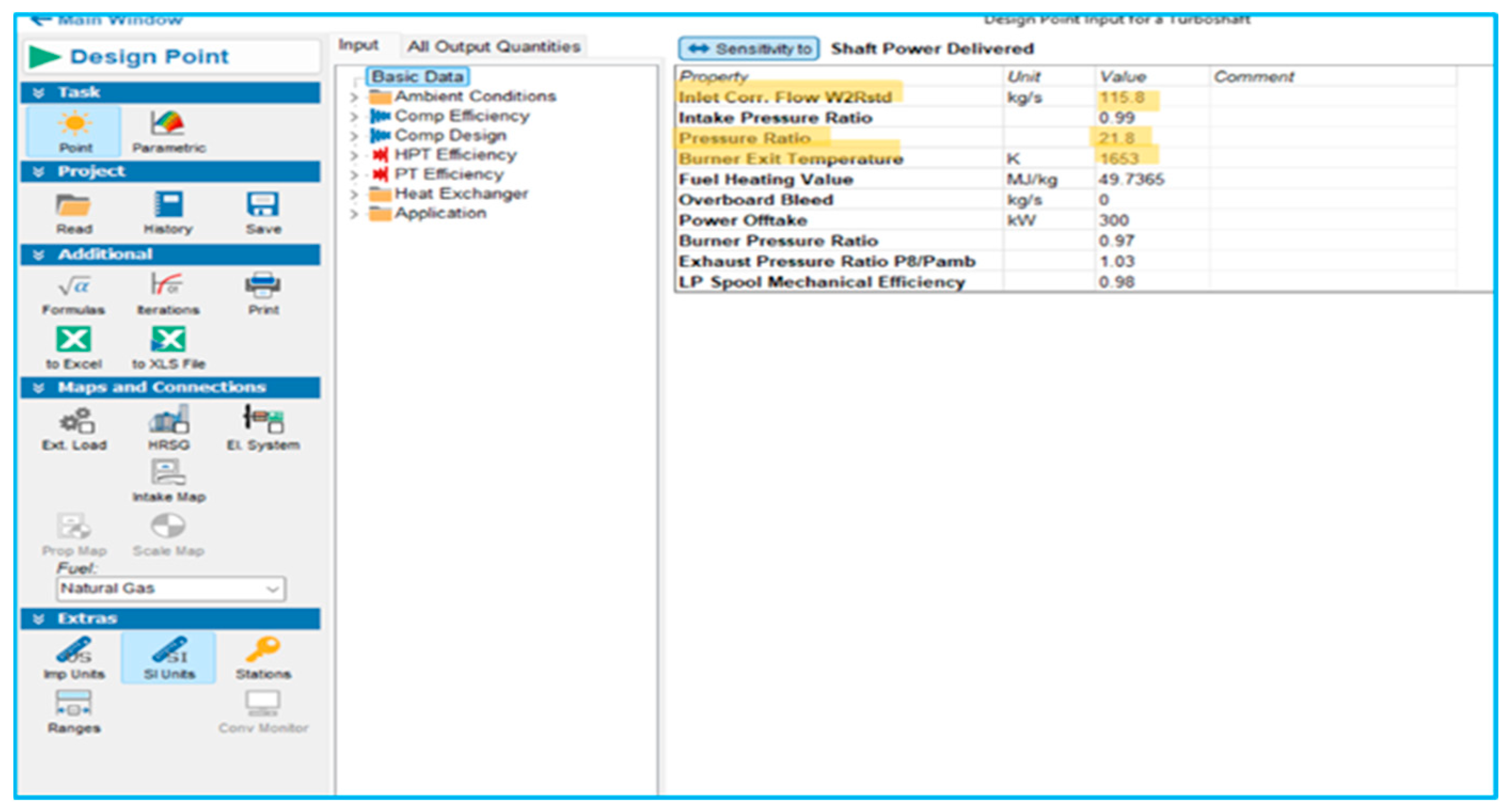

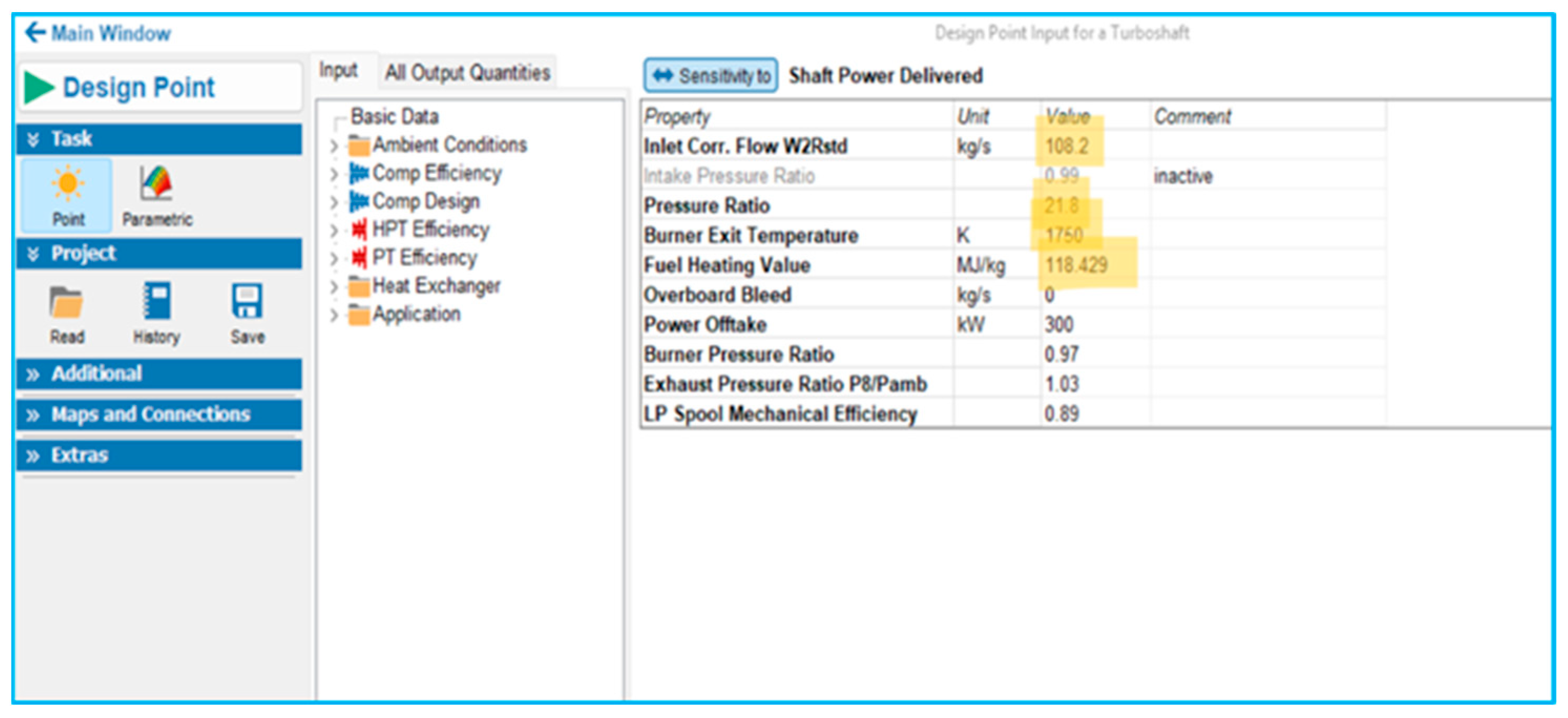

For Gasturb, regarding fuel properties and composition, input between Aspen and Gasturb is essential. For pure LNG and hydrogen models, Gasturb already allows the user to choose the fuel type. However, when dealing with LNG–hydrogen blends of varying calorific values, users need to define the fuel file input to Gasturb, such as molecular weight, LHV, and stoichiometric air requirement. However, the above two model validations in Aspen for reformulation in Gasturb, ensuring the simulation has identical hydrogen and LNG, are considered sufficient to demonstrate that both models are thermodynamically equivalent in terms of efficiency and output shaft power.

In practice, gas turbines never operate at stoichiometric AFR conditions because the flame temperature would be too high, leading to thermal NOx emissions and material failure. Instead, the gas turbine is to be run in lean, premixed combustion with a typical equivalence ratio of 0.3–0.6, which means the FAR is 30–60% of the stoichiometric AFR.