Density and Viscosity of CO2 Binary Mixtures with SO2, H2S, and CH4 Impurities: Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Thermodynamic Model Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

Method

3. Results and Discussion

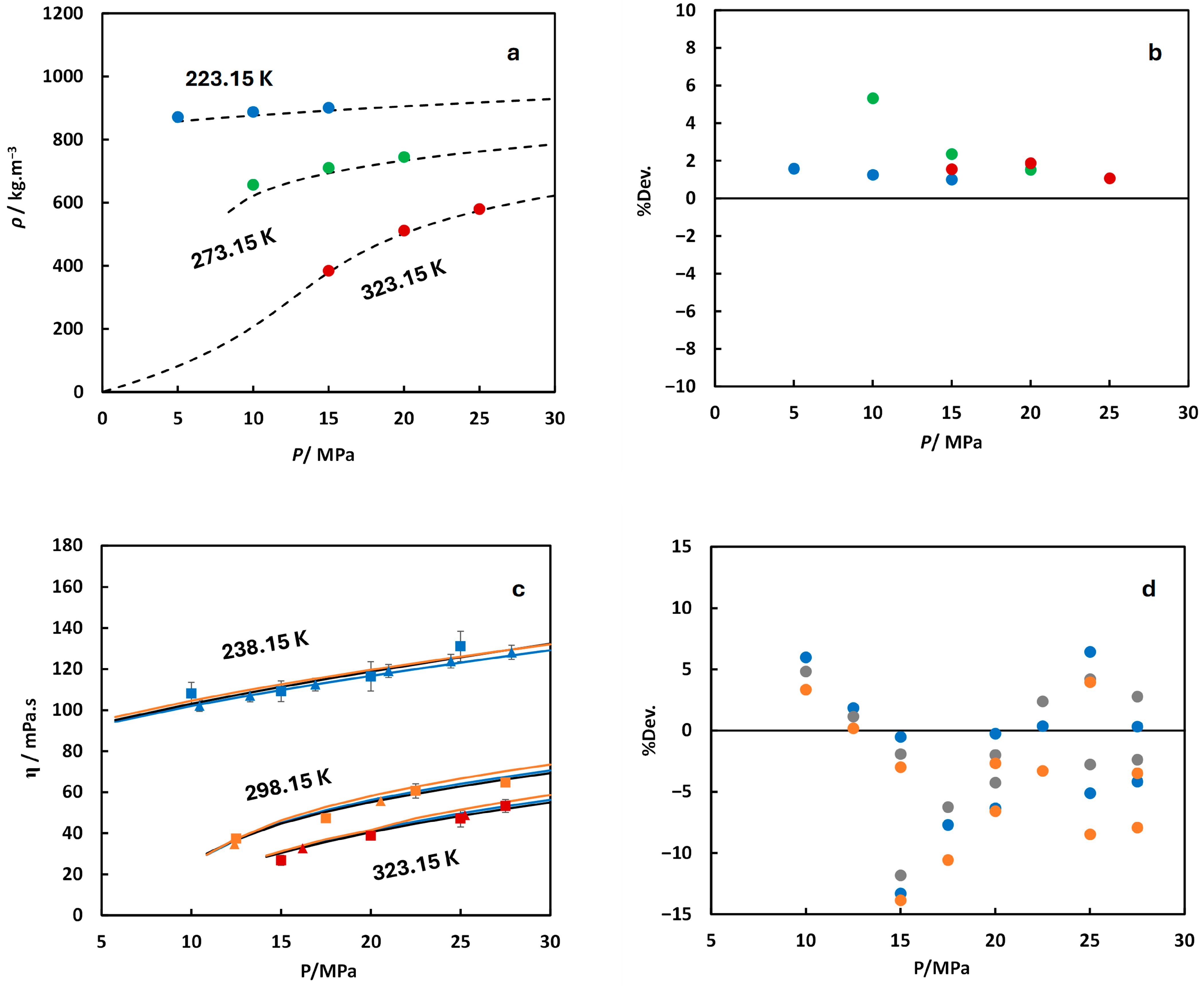

3.1. Validation with Model Predictions and Experimental Data

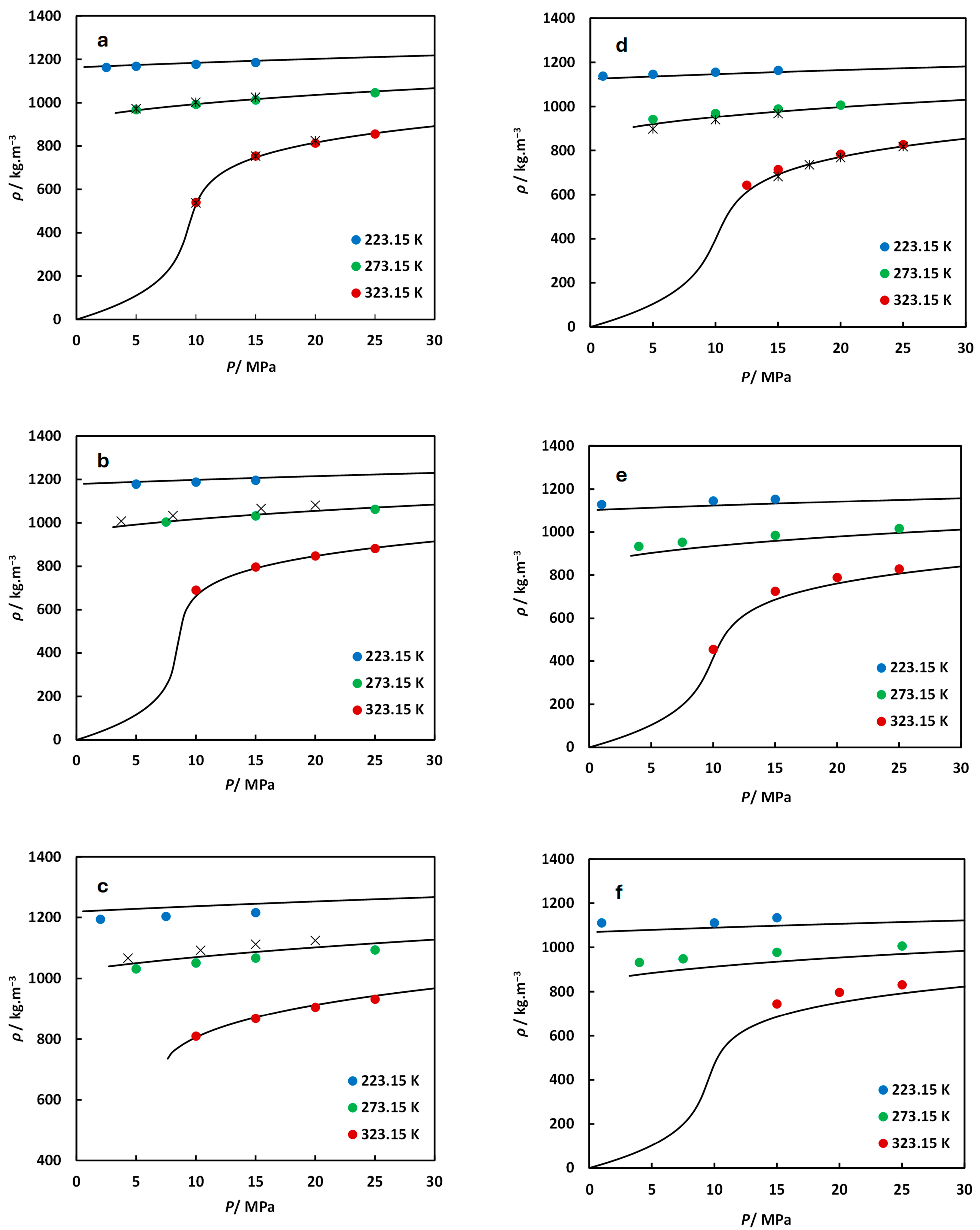

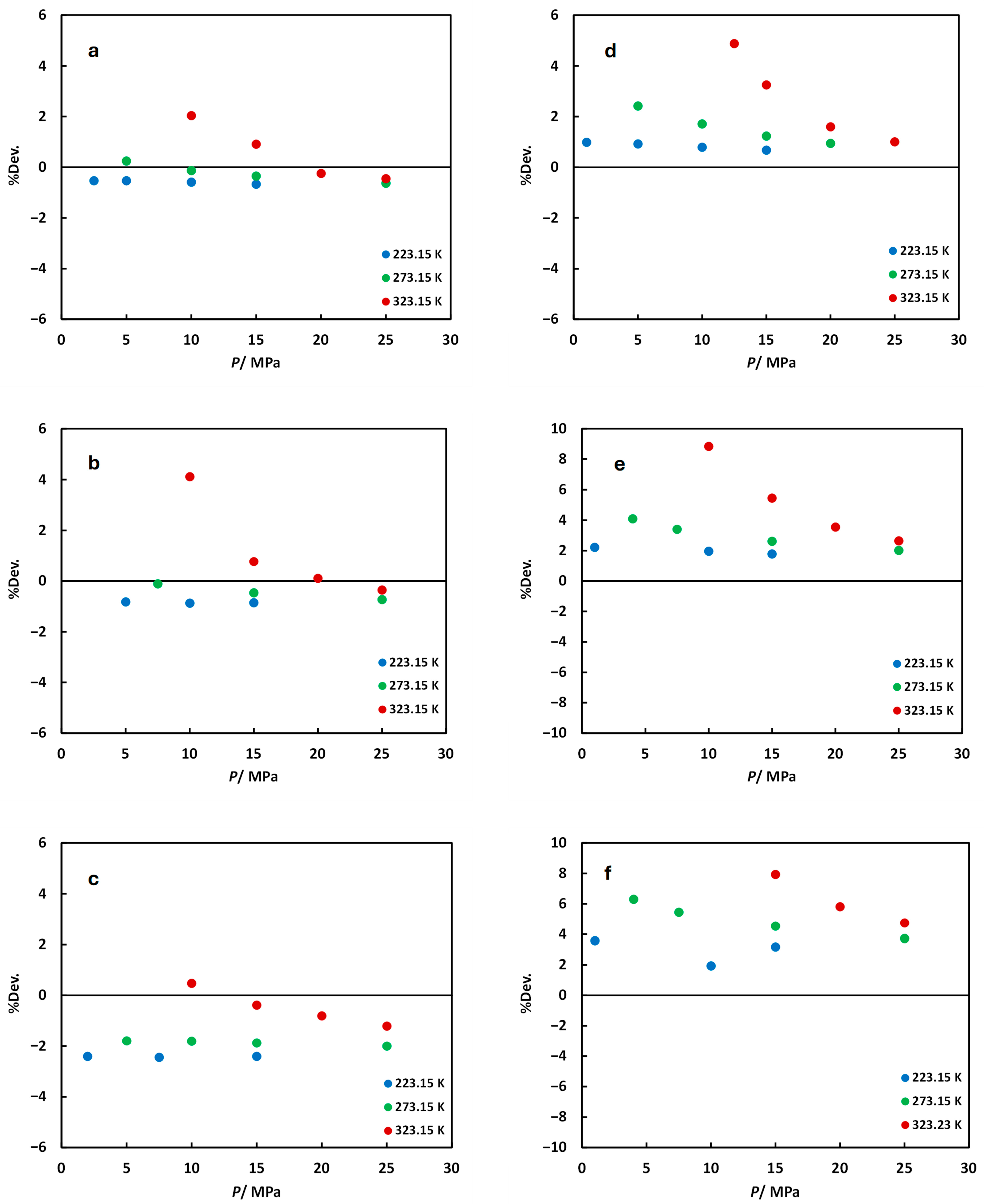

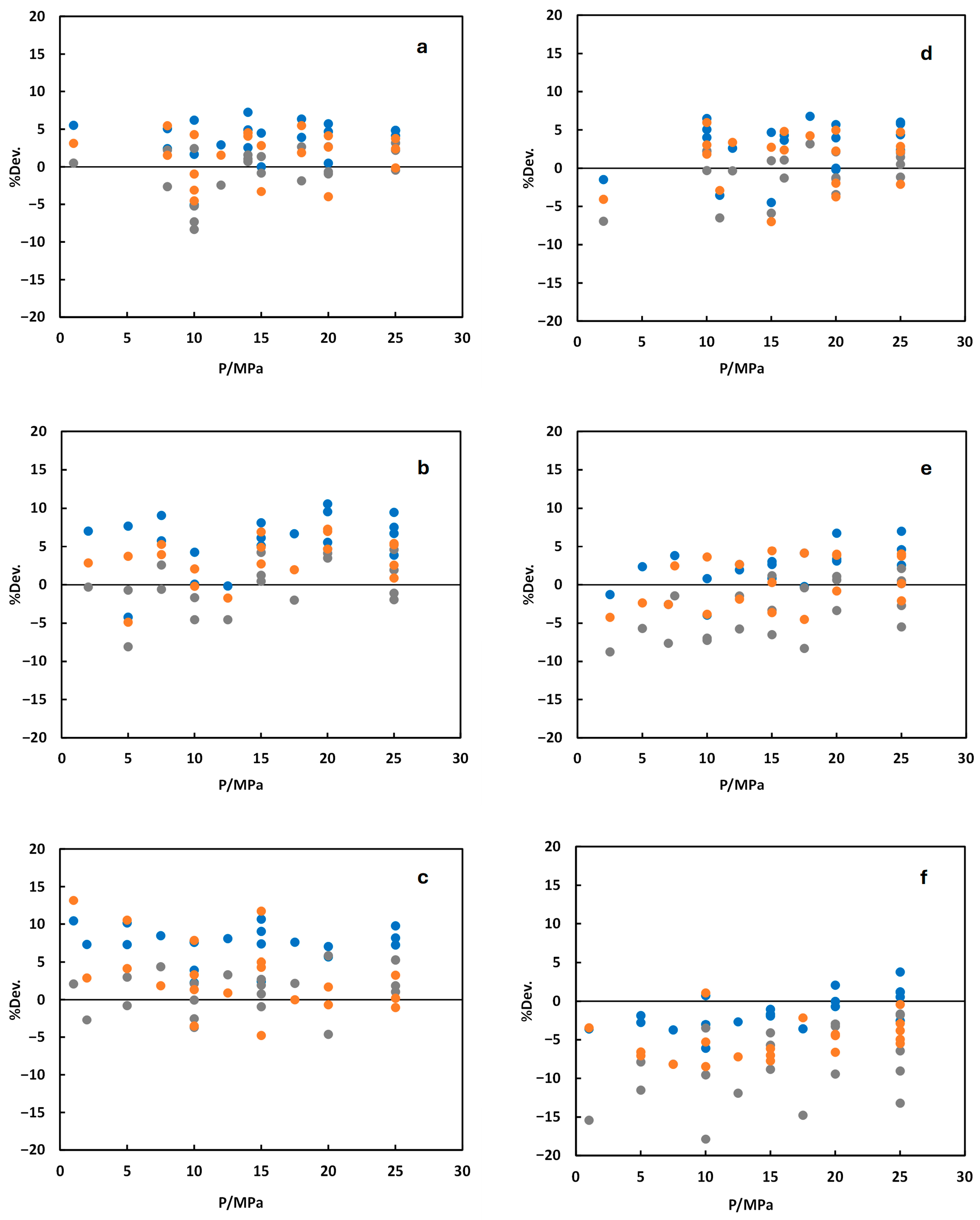

3.2. Density

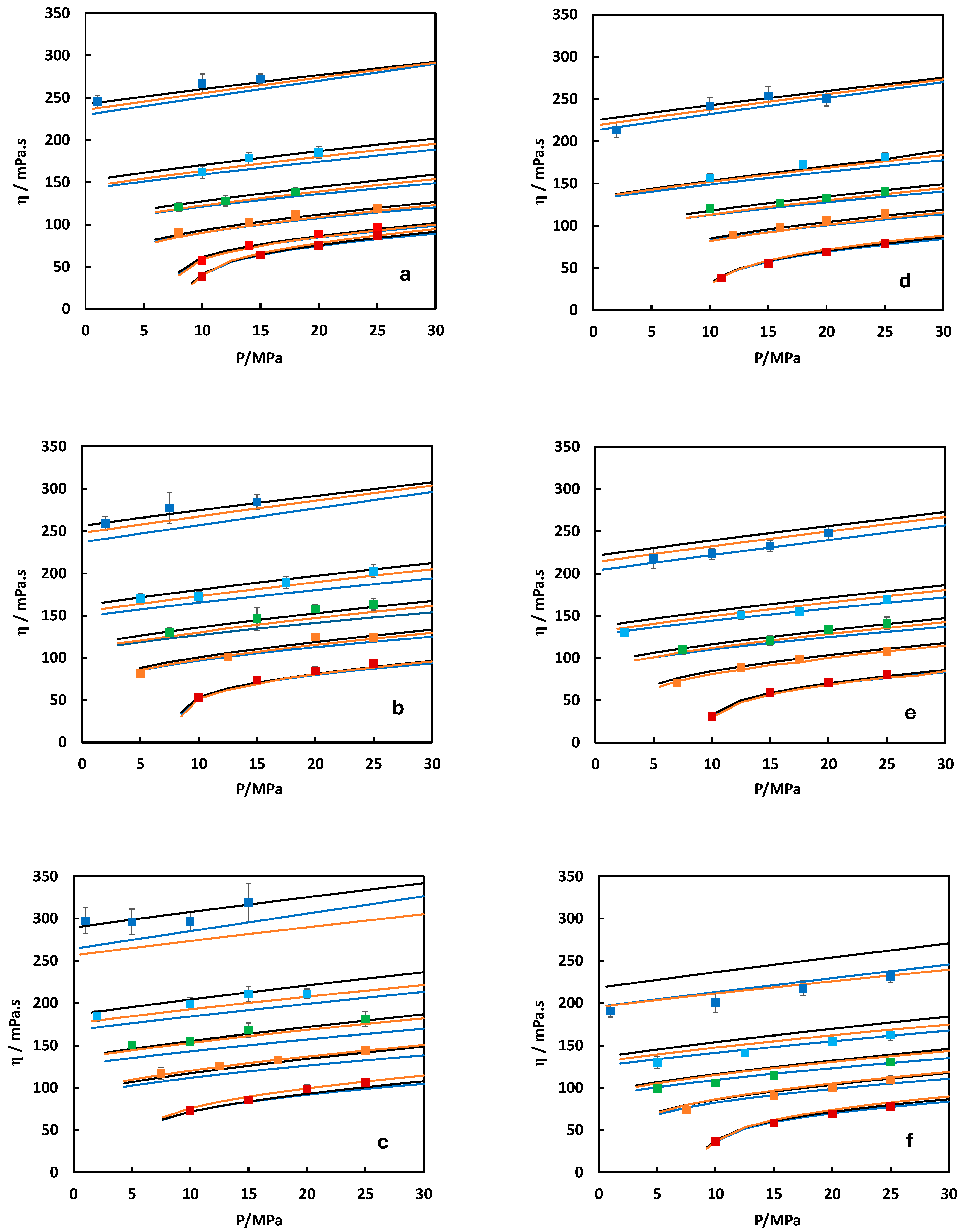

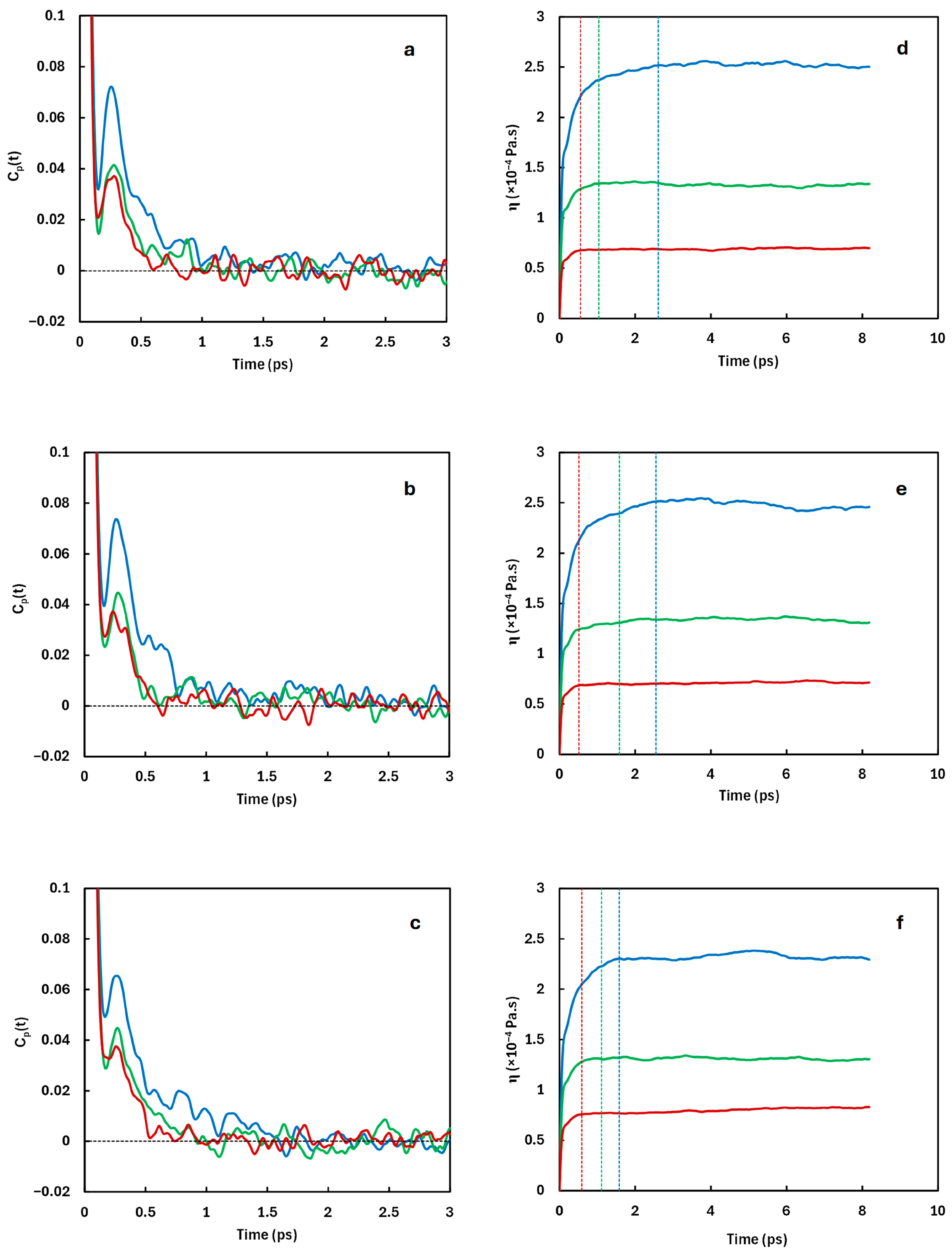

3.3. Viscosity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Thermodynamic Models

- Multi-Fluid Helmholtz Energy Approximation (MFHEA) Equations of States

Appendix A.2. Viscosity Models

- The Lennard Jones fluids (LJ)

- The extended corresponding states (ECS)

- The residual entropy viscosity (SRES)

References

- Council of the European Union. Paris Agreement on Climate Change. 2025. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/paris-agreement-climate (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Madejski, P.; Chmiel, K.; Subramanian, N.; Kuś, T. Methods and Techniques for CO2 Capture: Review of Potential Solutions and Applications in Modern Energy Technologies. Energies 2022, 15, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, R.T.J.; Fairweather, M.; Pourkashanian, M.; Woolley, R.M. The range and level of impurities in CO2 streams from different carbon capture sources. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2015, 36, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, M.; Corvaro, F.; Marchetti, B.; Terenzi, A. Thermodynamic challenges for CO2 pipelines design: A critical review on the effects of impurities, water content, and low temperature. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2022, 114, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyebuchi, V.E.; Kolios, A.; Hanak, D.P.; Biliyok, C.; Manovic, V. A systematic review of key challenges of CO2 transport via pipelines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2563–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapoy, A.; Nazeri, M.; Kapateh, M.; Burgass, R.; Coquelet, C.; Tohidi, B. Effect of impurities on thermophysical properties and phase behaviour of a CO2-rich system in CCS. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2013, 19, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddenberg, J.W.; Wilke, C.R. Viscosities of Some Mixed Gases; Remeen Press Division, Chemical Publishing Company: Gloucester, MA, USA, 1951; Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/j150492a008 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Rankine, A.O.; Smith, C.J. On the Viscous Properties and Molecular Dimensions of Silicane. Proc. Phys. Soc. Lond. 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jackson, W.M. Viscosities of The Binary Gas Mixtures, Methane-Carbon Dioxide and Ethylent-Argon. J. Phys. Chem. 1956, 60, 789–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewitt, K.J.; Thodos, G. Viscosities of binary mixtures in the dense gaseous state: The methane-carbon dioxide system. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1966, 44, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esper, G.J.; Bailey, D.M.; Holste, J.C.; Hall, K.R. Volumetric behavior of near-equimolar mixtures for CO2 + CH4 and CO2 + N2. Fluid Phase Equilibria 1989, 49, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobley, A.; Matthews, G.P.; Townsend, A. The use of a novel capillary flow viscometer for the study of the argon/carbon dioxide system. Int. J. Thermophys. 1989, 10, 1165–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouffer, C.E.; Kellerman, S.J.; Hall, K.R.; Holste, J.C.; Gammon, B.E.; Marsh, K.N. Densities of carbon dioxide + hydrogen sulfide mixtures from 220 K to 450 K at pressures up to 25 MPa. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2001, 46, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loianno, V.; Mensitieri, G. A novel dynamic method for the storage of calibration gas mixtures based on thermal mass flow controllers. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2022, 33, 65017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jakobsen, J.P.; Wilhelmsen, Ø.; Yan, J. PVTxy properties of CO2 mixtures relevant for CO2 capture, transport and storage: Review of available experimental data and theoretical models. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 3567–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Siyabi, I. Effect of Impurities on CO2 Stream Properties. Ph.D. Thesis, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, Scotland, 2013. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10399/2643 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Locke, C.R.; Stanwix, P.L.; Hughes, T.J.; Kisselev, A.; Goodwin, A.R.H.; Marsh, K.N.; May, E.F. Improved methods for gas mixture viscometry using a vibrating wire clamped at both ends. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2014, 59, 1619–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, B.; Girardon, S.; Bazer-Bachi, F.; Bergeot, G.; Marre, S.; Aymonier, C. Simultaneous measurement of fluids density and viscosity using HP/HT capillary devices. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 105, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghojogh, M.N. Impact of Impurities on Thermo-Physical Properties of CO2-Rich Systems: Experimental and Modelling. Ph.D. Thesis, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, Scotland, 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10399/2963 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Chapoy, A.; Owuna, F.J.; Burgass, R.; Ahmadi, P.; Stringari, P. Viscosity of the CO2 + CH4 Binary Systems from 238 to 423 K at Pressures up to 80 MPa. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2024, 69, 2152–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owuna, F.J.; Chapoy, A.; Ahmadi, P.; Burgass, R. Densities and Viscosities of Carbon Dioxide and Hydrogen Binary Systems: Experimental and Modeling. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2025, 70, 1858–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, P.; Chapoy, A.; Burgass, R. Thermophysical Properties of Typical CCUS Fluids: Experimental and Modeling Investigation of Density. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2020, 66, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, G.; Schmick, H. The Influence of Molecular Attractive Forces on the Viscosity of Gas Mixtures. Z. Phys. Chem. Abt. B 1930, 7, 130–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti, P.K.; Gray, P. Viscosities of Gaseous Mixtures Containing Polar Gases: Mixtures with One Polar Constituent. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1965, 61, 2422–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, P.K.; Ghosh, A.K. Viscosity of Polar–Quadrupolar Gas Mixtures. J. Chem. Phys. 1970, 52, 2719–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazeri, M.; Chapoy, A.; Valtz, A.; Coquelet, C. Tohidi, Densities and derived thermophysical properties of the 0.9505 CO2 + 0.0495 H2S mixture from 273 K to 353 K and pressures up to 41 MPa. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2016, 423, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazeri, M.; Chapoy, A.; Valtz, A.; Coquelet, C. Tohidi, New experimental density data and derived thermophysical properties of carbon dioxide—Sulphur dioxide binary mixture (CO2—SO2) in gas, liquid and supercritical phases from 273 K to 353 K and at pressures up to 42 MPa. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2017, 454, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno, B.; Artal, M.; Velasco, I.; Fernández, J.; Blanco, S.T. Influence of SO2 on CO2 Transport by Pipeline for Carbon Capture and Storage Technology: Evaluation of CO2/SO2 Cocapture. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 8641–8657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachet, V.; Creton, B.; De Bruin, T.; Bourasseau, E.; Desbiens, N.; Wilhelmsen, T.; Hammer, M. Equilibrium and transport properties of CO2 + N2O and CO2 + NO mixtures: Molecular simulation and equation of state modelling study. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2012, 322–323, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Nie, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, R.; Wang, J.; Yang, C.; Lin, A. Molecular dynamics investigation on shear viscosity of the mixed working fluid for supercritical CO2 Brayton cycle. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2022, 182, 105533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, G.A.; Vrabec, J.; Hasse, H. Shear viscosity and thermal conductivity of quadrupolar real fluids from molecular simulation. Mol. Simul. 2005, 31, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimoli, C.G.; Maginn, E.J.; Abreu, C.R.A. Force field comparison and thermodynamic property calculation of supercritical CO2 and CH4 using molecular dynamics simulations. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2014, 368, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimoli, C.G.; Maginn, E.J.; Abreu, C.R.A. Transport properties of carbon dioxide and methane from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 141, 134101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.P.; Aktulga, H.M.; Berger, R.; Bolintineanu, D.S.; Brown, W.M.; Crozier, P.S.; Veld, P.J.I.; Kohlmeyer, A.; Moore, S.G.; Nguyen, T.D. LAMMPS-a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2022, 271, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potoff, J.J.; Siepmann, J.I. Vapor-liquid equilibria of mixtures containing alkanes, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen. AIChE J. 2001, 47, 1676–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.G.; Yung, K.H. Carbon Dioxide’s Liquid-Vapor Coexistence Curve and Critical Properties As Predicted by a Simple Molecular Model. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 12021–12024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, D.; Ramdin, M.; Vlugt, T.J.H. Thermophysical Properties and Phase Behavior of CO2 with Impurities: Insight from Molecular Simulations. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2024, 69, 2735–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgass, R.; Chapoy, A. Dehydration requirements for CO2 and impure CO2 for ship transport. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2023, 572, 113830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, T.; Herrig, S.; Bell, I.H.; Beckmüller, R.; Lemmon, E.W.; Thol, M.; Span, R. EOS-CG-2021: A Mixture Model for the Calculation of Thermodynamic Properties of CCS Mixtures. Int. J. Thermophys. 2023, 44, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galliero, G.; Boned, C.; Baylaucq, A.; Montel, F. High-pressure acid-gas viscosity correlation. SPE J. 2010, 15, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, Y. Relation between the transport coefficients and the internal entropy of simple systems. Phys. Rev. A 1977, 15, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, Y. A quasi-universal scaling law for atomic transport in simple fluids. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1999, 11, 5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, H.J.M.; Cohen, E.G.D. Analysis of the transport coefficients for simple dense fluids: The diffusion and bulk viscosity coefficients. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 1976, 83, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Car, R.; Parrinello, M. Unified approach for molecular dynamics and density-functional theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1985, 55, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, G. Molecular Simulation Studies on Thermophysical Properties; Springer: Braunschweig, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S. Molecular Simulations: Fundamentals and Practice; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://search.worldcat.org/title/1002291342 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Allen, M.P.; Tildesley, D.J. Computer Simulation of Liquids, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, W.G.; Evans, D.J.; Hickman, R.B.; Ladd, A.J.C.; Ashurst, W.T.; Moran, B. Lennard-Jones triple-point bulk and shear viscosities. Green-Kubo theory, Hamiltonian mechanics, and nonequilibrium molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. A 1980, 22, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.J.; Morriss, G.P. Statistical Mechanics of Nonequilbrium Liquids; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanzig, R. Elementary derivation of time-correlation formulas for transport coefficients. J. Chem. Phys. 1964, 40, 2527–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deublein, S.; Eckl, B.; Stoll, J.; Lishchuk, S.V.; Guevara-Carrion, G.; Glass, C.W.; Merker, T.; Bernreuther, M.; Hasse, H.; Vrabec, J. Ms2: A molecular simulation tool for thermodynamic properties. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2011, 182, 2350–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svehla, R.A. Estimated Viscosities and Thermal Conductivities of Gases at High Temperatures; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Siepmann, J.I. Pressure Dependence of the Vapor−Liquid−Liquid Phase Behavior in Ternary Mixtures Consisting of n-Alkanes, n-Perfluoroalkanes, and Carbon Dioxide. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 2911–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; Du, Y.; Zhang, F.; Jiaqiang, E.; Chen, J.; Leng, E. Widom line of supercritical CO2 calculated by equations of state and molecular dynamics simulation. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 62, 102075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widom, B. Some topics in the theory of fluids. J. Chem. Phys. 1963, 39, 2808–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maginn, E.J.; Messerly, R.A.; Carlson, D.J.; Roe, D.R.; Elliot, J.R. Best Practices for Computing Transport Properties 1. Self-Diffusivity and Viscosity from Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics [Article v1.0]. Living J. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018, 1, 6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baladão, L.F.; Soares, R.P.; Fernandes, P.R. Comparison of the GERG-2008 and Peng-Robinson Equations of State for Natural Gas Mixtures. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2018, 8, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernert, J.; Span, R. EOS–CG: A Helmholtz energy mixture model for humid gases and CCS mixtures. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2016, 93, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Span, R.; Wagner, W. A New Equation of State for Carbon Dioxide Covering the Fluid Region from the Triple-Point Temperature to 1100 K at Pressures up to 800 MPa. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 25, 1509–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setzmann, U.; Wagner, W. A New Equation of State and Tables of Thermodynamic Properties for Methane Covering the Range from the Melting Line to 625 K at Pressures up to 1000 MPa. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 20, 1061–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Wu, J.; Zhang, P.; Lemmon, E.W. A Helmholtz Energy Equation of State for Sulfur Dioxide. J. Chem. 2016, 61, 2859–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, E.W.; Span, R. Short Fundamental Equations of State for 20 Industrial Fluids. J. Chem. 2006, 51, 785–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, O.; Wagner, W. The GERG-2008 Wide-Range Equation of State for Natural Gases and Other Mixtures: An Expansion of GERG-2004. J. Chem. 2012, 57, 3032–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galliéro, G.; Boned, C.; Baylaucq, A. Molecular Dynamics Study of the Lennard−Jones Fluid Viscosity: Application to Real Fluids. Ind. Chem. 2005, 44, 6963–6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, J.F.; Hanley, H.J.M. Prediction of Transport Properties.1. Viscosity of Fluids and Mixtures. Ind. Chem. 1981, 20, 323–332. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/sharingguidelines (accessed on 25 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.F.; Ely, M.L. NIST Standard Rejerence Database 4: NIST Thermophysical Properties of Hydrocarbon Mixtures, Washington, DC, USA. 1990. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/srd/Supertrapp.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Young, J.M.; Bell, I.H.; Harvey, A.H. Entropy scaling of viscosity for molecular models of molten salts. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 158, 024502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, I.H. Entropy Scaling of Viscosity—I: A Case Study of Propane. J. Chem. 2020, 65, 3203–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lötgering-Lin, O.; Gross, J. Group Contribution Method for Viscosities Based on Entropy Scaling Using the Perturbed-Chain Polar Statistical Associating Fluid Theory. Ind. Chem. 2015, 54, 7942–7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lötgering-Lin, O.; Fischer, M.; Hopp, M.; Gross, J. Pure Substance and Mixture Viscosities Based on Entropy Scaling and an Analytic Equation of State. Ind. Chem. 2018, 57, 4095–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, P.D.; Janzen, A.R.; Aziz, R.A. Empirical Equations to Calculate 16 of the Transport Collision Integrals Ω(l, s)* for the Lennard-Jones (12–6) Potential. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 57, 1100–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xiao, X.; Thol, M.; Richter, M.; Bell, I.H. Linking Viscosity to Equations of State Using Residual Entropy Scaling Theory. Int. J. 2022, 43, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

): experimental data from Nazari et al. [19] (xSO2 = 0.0497 measured at 273.55 K and 322.49 K and xH2S = 0.0495 measured at 272.56 K and 322.42 K); (×): experimental data from Gimeno et al. [28] (xCO2 = 0.8969 and 0.8029 measured at 273.15 ± 0.05 K); (▬): predicted from MFHEA model.

): experimental data from Nazari et al. [19] (xSO2 = 0.0497 measured at 273.55 K and 322.49 K and xH2S = 0.0495 measured at 272.56 K and 322.42 K); (×): experimental data from Gimeno et al. [28] (xCO2 = 0.8969 and 0.8029 measured at 273.15 ± 0.05 K); (▬): predicted from MFHEA model.

): experimental data from Nazari et al. [19] (xSO2 = 0.0497 measured at 273.55 K and 322.49 K and xH2S = 0.0495 measured at 272.56 K and 322.42 K); (×): experimental data from Gimeno et al. [28] (xCO2 = 0.8969 and 0.8029 measured at 273.15 ± 0.05 K); (▬): predicted from MFHEA model.

): experimental data from Nazari et al. [19] (xSO2 = 0.0497 measured at 273.55 K and 322.49 K and xH2S = 0.0495 measured at 272.56 K and 322.42 K); (×): experimental data from Gimeno et al. [28] (xCO2 = 0.8969 and 0.8029 measured at 273.15 ± 0.05 K); (▬): predicted from MFHEA model.

| CO2 TraPPE [35] | CH4 TraPPE [53] | SO2 Svehla [52] | H2S Svehla [52] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (K) | C-C | 27.0 | 148.00 | 335.4 | 301.1 |

| O-O | 79.0 | ||||

| (Å) | C-C | 2.8 | 3.73 | 4.112 | 3.623 |

| O-O | 3.05 | ||||

| q (e) | C | +0.7 | - | - | - |

| O | −0.35 | ||||

| O-C-O | 180 | - | - | - | |

| C-O | 1.16 | ||||

| Mixture | x | Density | Viscosity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFHEA | LJ | SRES | ST | ||

| CO2 + CH4 | (xCH4 = 0.25) | 2.00 | 4.36 | 3.89 | 5.61 |

| CO2 + SO2 | (xSO2 = 0.05) | 0.60 | 4.20 | 2.44 | 3.25 |

| CO2 + SO2 | (xSO2 = 0.10) | 0.92 | 6.20 | 2.78 | 3.91 |

| CO2 + SO2 | (xSO2 = 0.20) | 1.60 | 7.41 | 2.58 | 4.10 |

| CO2 + H2S | (xH2S = 0.05) | 1.69 | 3.98 | 2.75 | 3.67 |

| CO2 + H2S | (xH2S = 0.10) | 3.51 | 2.89 | 4.02 | 2.96 |

| CO2 + H2S | (xH2S = 0.20) | 4.72 | 2.24 | 8.33 | 5.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahmoodi, M.H.; Ahmadi, P.; Chapoy, A. Density and Viscosity of CO2 Binary Mixtures with SO2, H2S, and CH4 Impurities: Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Thermodynamic Model Validation. Gases 2025, 5, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/gases5040028

Mahmoodi MH, Ahmadi P, Chapoy A. Density and Viscosity of CO2 Binary Mixtures with SO2, H2S, and CH4 Impurities: Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Thermodynamic Model Validation. Gases. 2025; 5(4):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/gases5040028

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahmoodi, Mohammad Hassan, Pezhman Ahmadi, and Antonin Chapoy. 2025. "Density and Viscosity of CO2 Binary Mixtures with SO2, H2S, and CH4 Impurities: Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Thermodynamic Model Validation" Gases 5, no. 4: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/gases5040028

APA StyleMahmoodi, M. H., Ahmadi, P., & Chapoy, A. (2025). Density and Viscosity of CO2 Binary Mixtures with SO2, H2S, and CH4 Impurities: Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Thermodynamic Model Validation. Gases, 5(4), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/gases5040028