Nanomodified Nexavar Enhances Efficacy in Caco-2 Cells via Targeting Aspartate β-Hydroxylase-Driven Mitochondrial Cell Death

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Drug-Loaded Nanospanlastics Prepared by the Thin-Film Hydration Method

2.2. Cell Lines

2.3. Preparation of Drugs

2.4. Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assay

2.5. Annexin-V Assay

2.6. Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Production

2.7. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) Copy Number

2.8. Detection of Accumulated Mitochondria

2.9. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.10. Flow Cytometric Assay

2.11. Immunoblotting Analysis

2.12. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.13. Bioinformatic and Data Analysis

3. Results

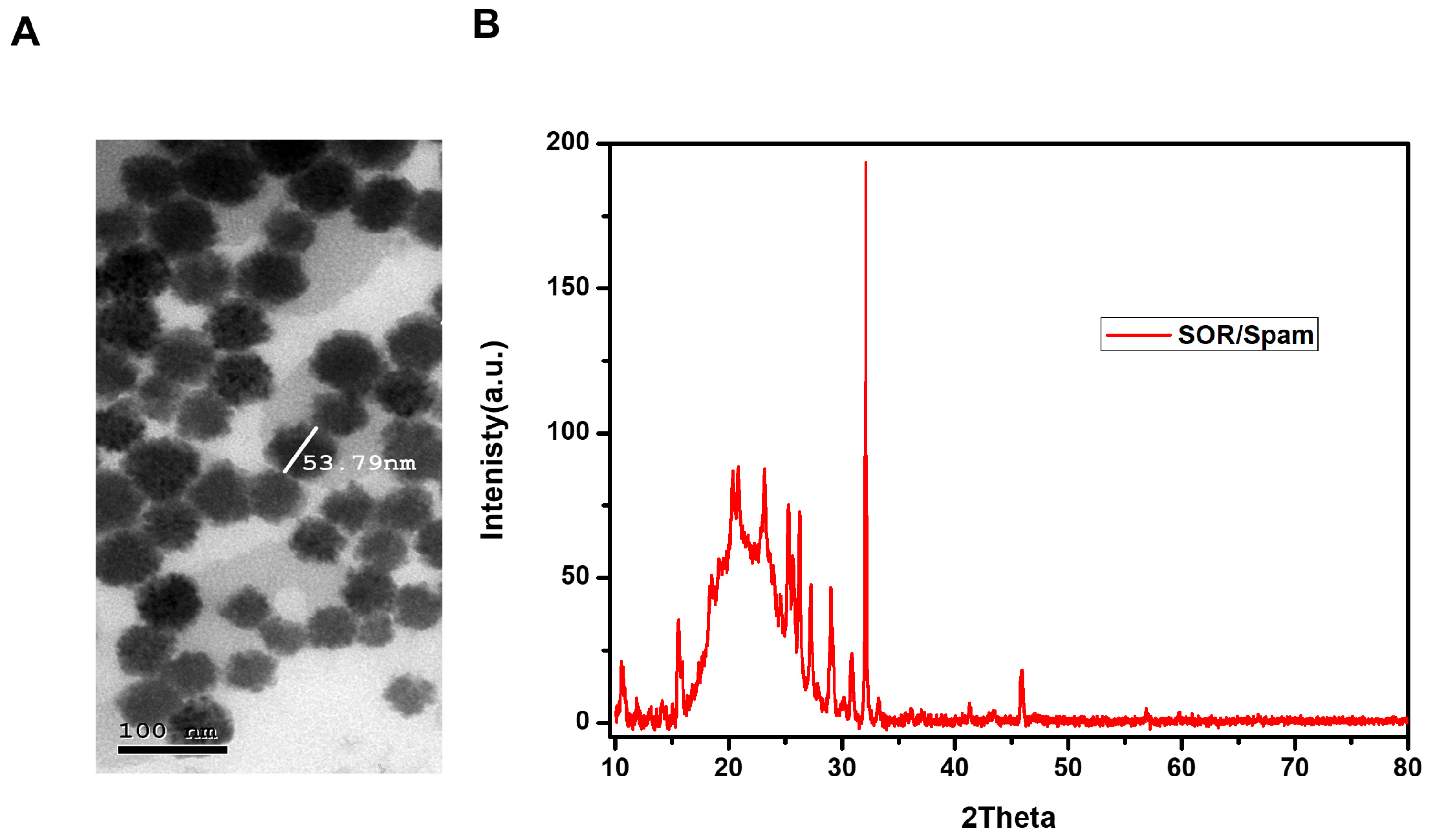

3.1. Nanomodified Particles of Nexavar (Nano-Nexavar)

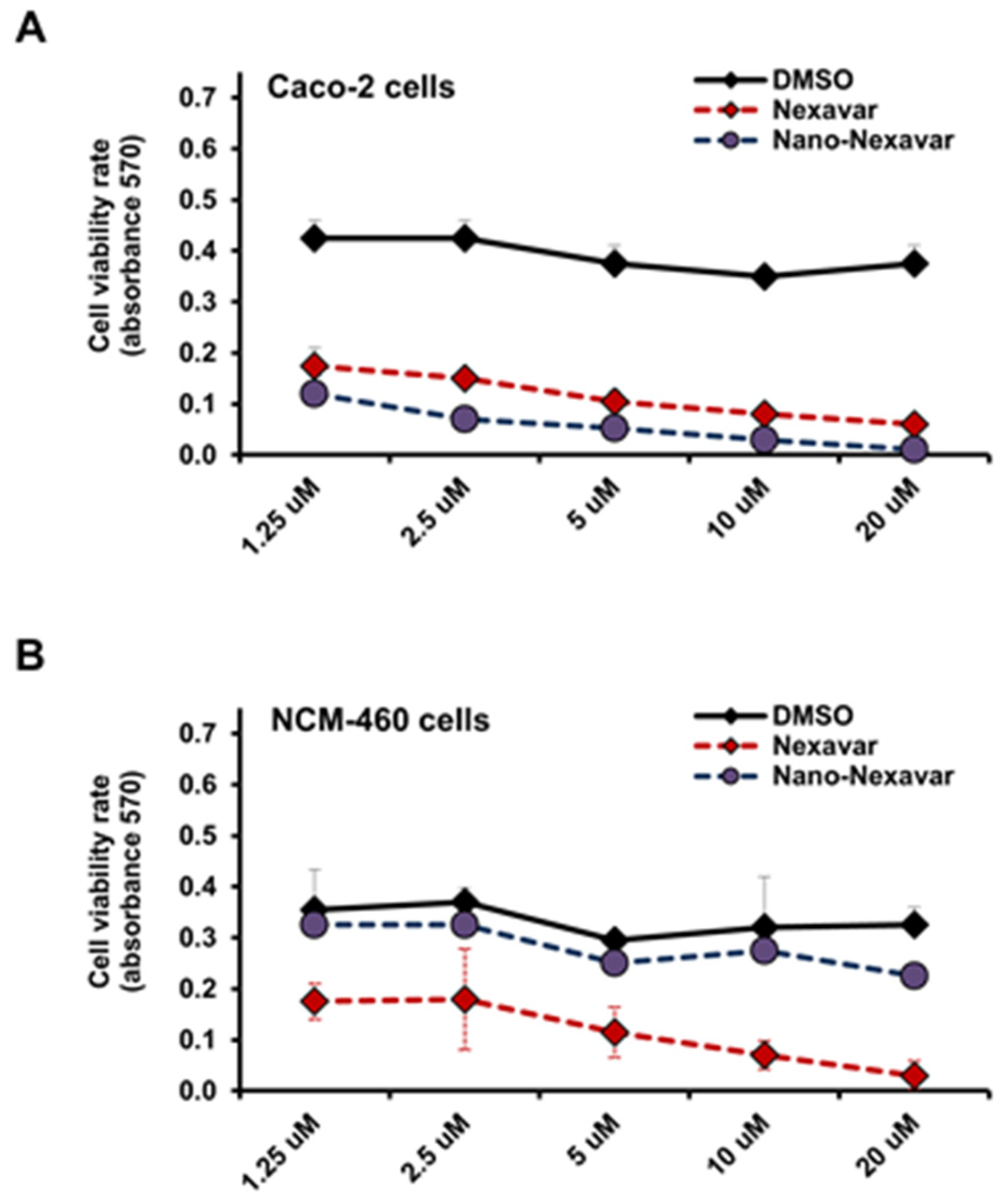

3.2. Selective Modulation of Colon Cancer Cell Proliferation Through Nano-Nexavar Treatment

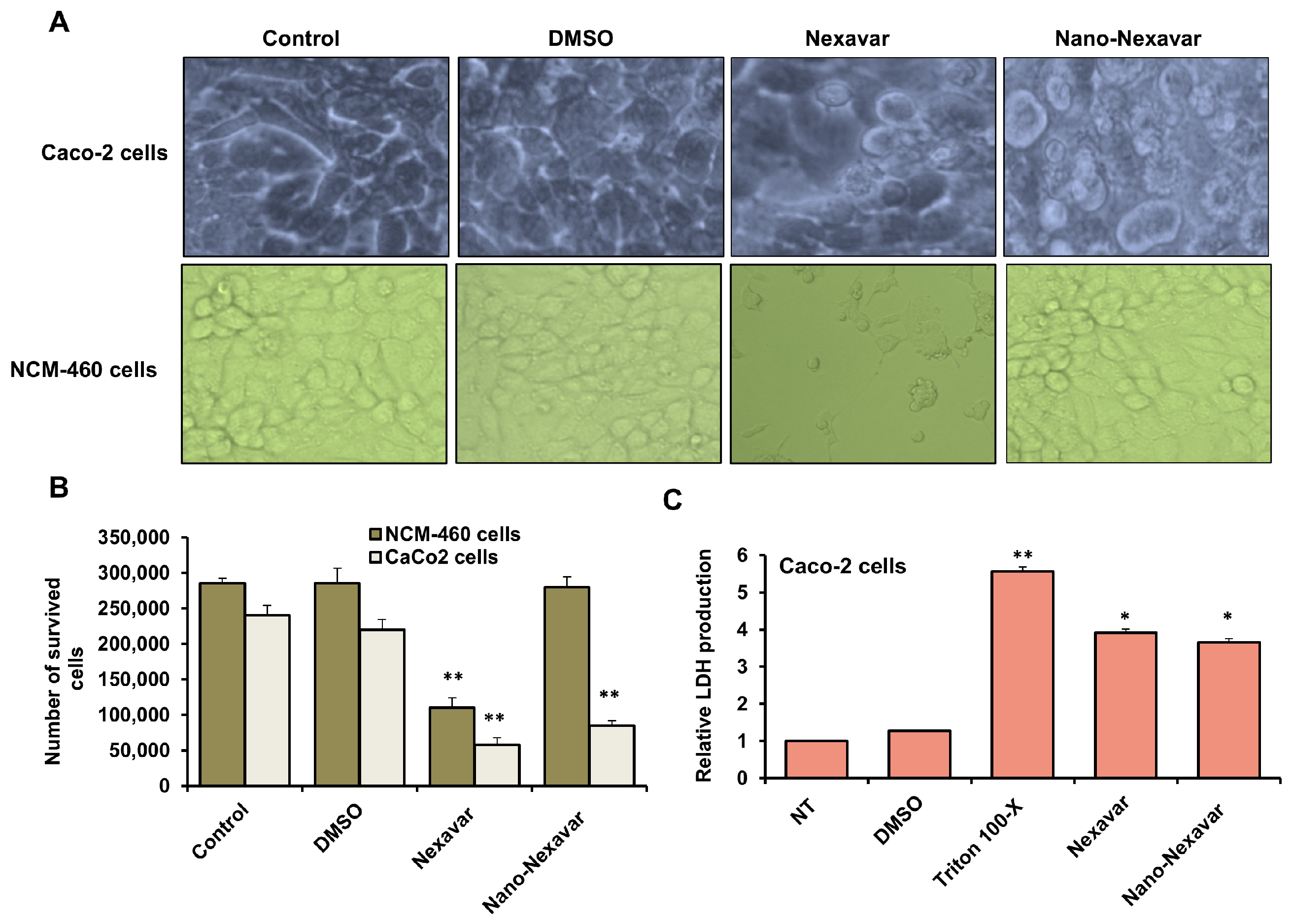

3.3. Cytotoxic Effects and Morphological Changes in Colon Cancer Following Treatment with Nexavar and Nano-Nexavar

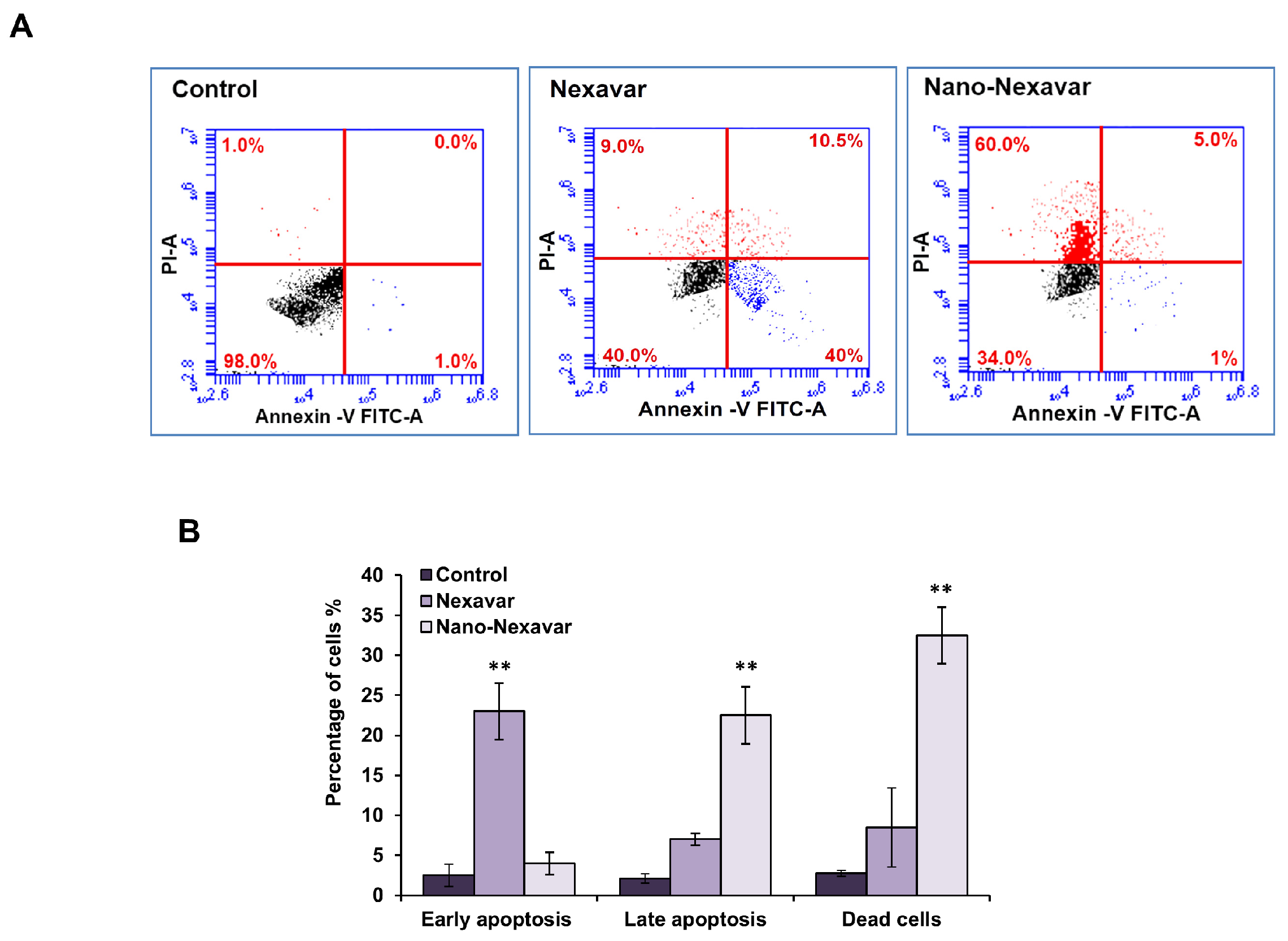

3.4. Nano-Nexavar Exhibits Significant Effects Overall Cytotoxicity on Caco-2 Cells

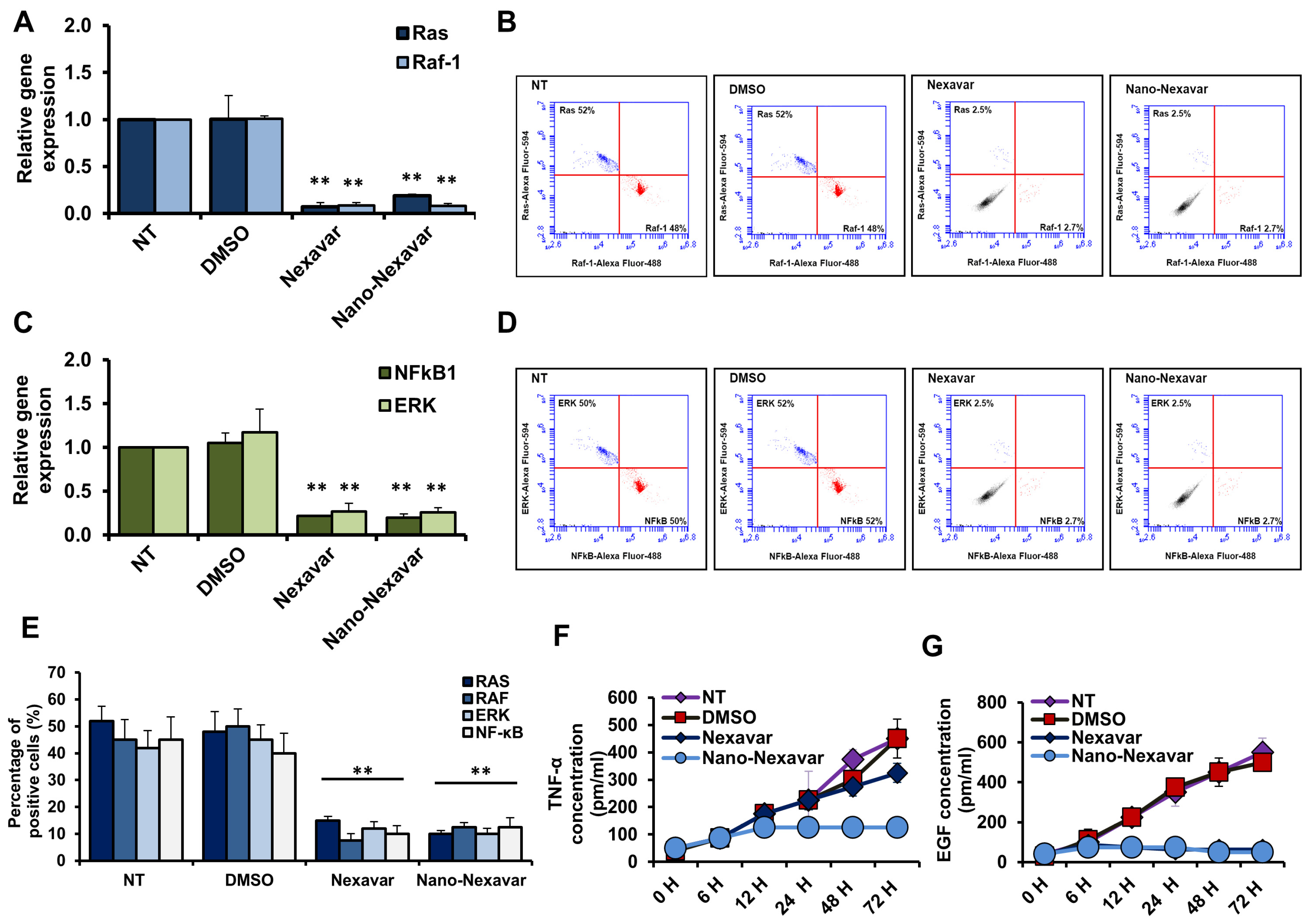

3.5. Nano-Nexavar Effectively Blocks MAPK Signaling, Similar to How Nexavar Works

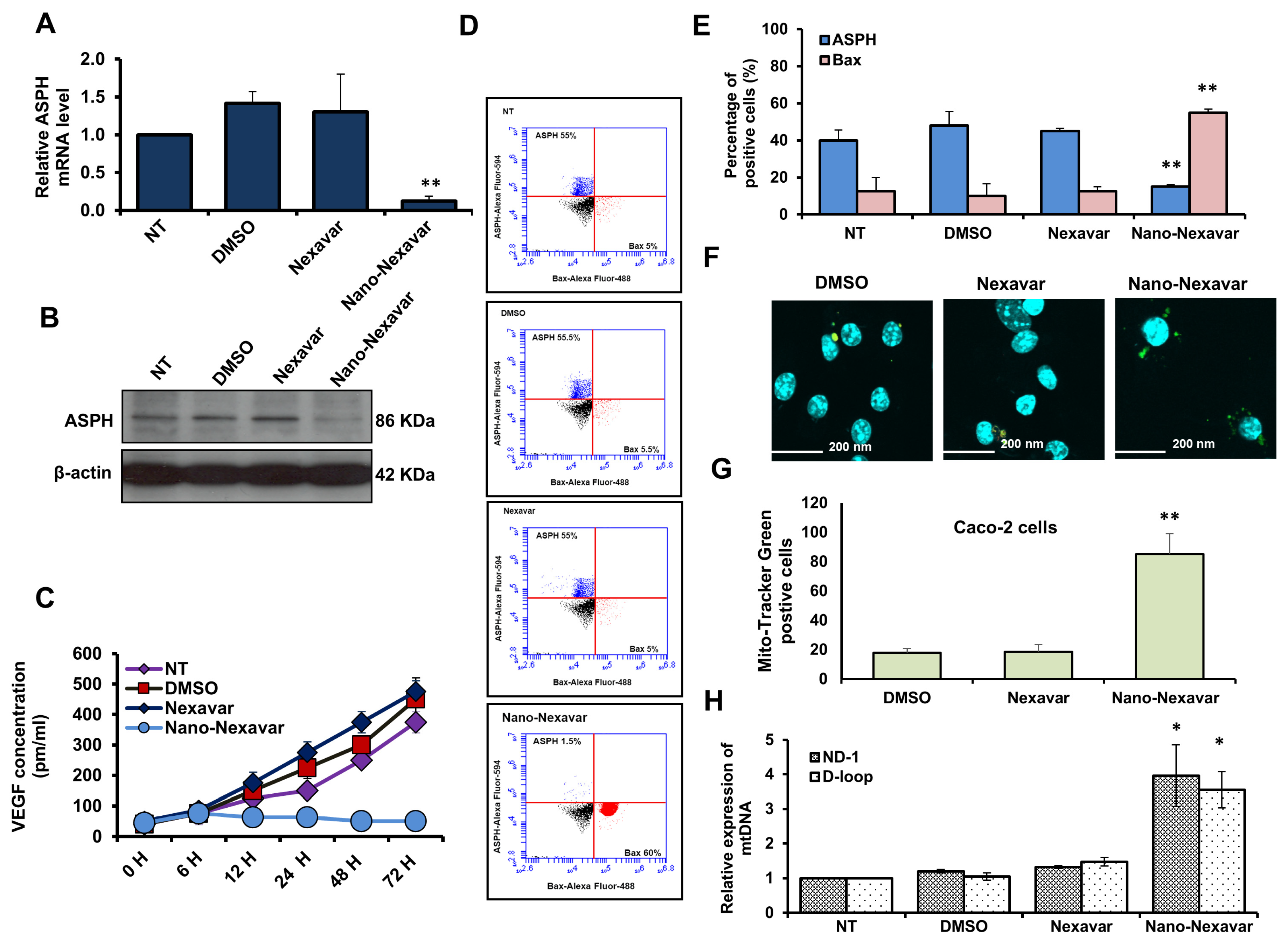

3.6. Nano-Nexavar Targets Mitochondrial-ASPH in Caco-2 Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dekker, E.; Tanis, P.J.; Vleugels, J.L.A.; Kasi, P.M.; Wallace, M.B. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 2019, 394, 1467–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalitzky, M.K.; Zhou, P.P.; Goffredo, P.; Guyton, K.; Sherman, S.K.; Gribovskaja-Rupp, I.; Hassan, I.; Kapadia, M.R.; Hrabe, J.E. Characteristics and symptomatology of colorectal cancer in the young. Surgery 2023, 173, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chang, Z.; Wang, J.; Ding, K.; Pan, S.; Hu, H.; Tang, Q. Unhealthy lifestyle factors and the risk of colorectal cancer: A Mendelian randomization study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.S.; Karuniawati, H.; Jairoun, A.A.; Urbi, Z.; Ooi, D.J.; John, A.; Lim, Y.C.; Kibria, K.M.K.; Mohiuddin, A.K.M.; Ming, L.C.; et al. Colorectal Cancer: A Review of Carcinogenesis, Global Epidemiology, Current Challenges, Risk Factors, Preventive and Treatment Strategies. Cancers 2022, 14, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anyane-Yeboa, A.; Bermudez, H.; Fredericks, M.; Yoguez, N.; Ibekwe-Agunanna, L.; Daly, J.; Hildebrant, E.; Kuckreja, M.; Hindin, R.; Pelton-Cairns, L.; et al. The revised colorectal cancer screening guideline and screening burden at community health centers. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisa, A.; Elshal, M.F.; Muawia, S.; Khalil, H. The combination of sitagliptin and bee honey extract potentiates the anti-proliferative properties of 5-fluorouracil on Caco-2 cell line without detectable inflammatory events. Clin. Tradit. Med. Pharmacol. 2024, 5, 200165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewitz, L.; Tumber, A.; Pfeffer, I.; McDonough, M.A.; Schofield, C.J. Aspartate/asparagine-β-hydroxylase: A high-throughput mass spectrometric assay for discovery of small molecule inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wang, X.; Hu, J.; Bai, B.; Zhu, H. Diverse molecular functions of aspartate β-hydroxylase in cancer (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2020, 44, 2364–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturla, L.-M.; Tong, M.; Hebda, N.; Gao, J.; Thomas, J.-M.; Olsen, M.; de la Monte, S.M. Aspartate-β-hydroxylase (ASPH): A potential therapeutic target in human malignant gliomas. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Du, H.; Hu, Y.; Xing, X.; Cheng, X.; Yan, Y.; Li, Z. Aspartate β-Hydroxylase Serves as a Prognostic Biomarker for Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Gastric Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, R.; Costa, D.; Mastracci, L.; Grillo, F.; Olsen, M.J.; Barboro, P.; Poggi, A.; Ferrari, N. Aspartate-β-Hydroxylase: A Promising Target to Limit the Local Invasiveness of Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smahelova, J.; Pokryvkova, B.; Stovickova, E.; Grega, M.; Vencalek, O.; Smahel, M.; Koucky, V.; Malerova, S.; Klozar, J.; Tachezy, R. Aspartate-β-hydroxylase and hypoxia marker expression in head and neck carcinomas: Implications for HPV-associated tumors. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2024, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacan, T.; Nayir, E.; Altun, A.; Kilickap, S.; Babacan, N.A.; Ataseven, H.; Kaya, T. Antitumor activity of sorafenib on colorectal cancer. J. Oncol. Sci. 2016, 2, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.; Carter, C.; Lynch, M.; Lowinger, T.; Dumas, J.; Smith, R.A.; Schwartz, B.; Simantov, R.; Kelley, S. Discovery and development of sorafenib: A multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, C.J.; Sissung, T.M.; Kim, A.; Jain, L.; Woo, S.; Gardner, E.R.; Kirkland, C.T.; Troutman, S.M.; English, B.C.; Richardson, E.D.; et al. Sorafenib Is an Inhibitor of UGT1A1 but Is Metabolized by UGT1A9: Implications of Genetic Variants on Pharmacokinetics and Hyperbilirubinemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 2099–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Erp, N.P.; Gelderblom, H.; Guchelaar, H.-J. Clinical pharmacokinetics of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2009, 35, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Cao, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X.; McNabola, A.; Wilkie, D.; Wilhelm, S.; Lynch, M.; Carter, C. Sorafenib Blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK Pathway, Inhibits Tumor Angiogenesis, and Induces Tumor Cell Apoptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 11851–11858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shao, A. Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy and Its Role in Overcoming Drug Resistance. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, J. Application of Nanomaterials in the Prevention, Detection, and Treatment of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, I.; El-Dahmy, R.M.; Elshafeey, A.H.; Abd El Gawad, N.A.; El Gazayerly, O.N. Tripling the Bioavailability of Rosuvastatin Calcium Through Development and Optimization of an In-Situ Forming Nanovesicular System. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fadl, H.M.A.; Hagag, N.M.; El-Shafei, R.A.; Khayri, M.H.; El-Gedawy, G.; El Maksoud, A.I.A.; Mohamed, D.D.; Mohamed, D.D.; El Halfawy, I.; Khoder, A.I.; et al. Effective Targeting of Raf-1 and Its Associated Autophagy by Novel Extracted Peptide for Treating Breast Cancer Cells. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabous, E.; Alalem, M.; Awad, A.M.; Elawdan, K.A.; Tabl, A.M.; Elsaka, S.; Said, W.; Guirgis, A.A.; Khalil, H. Regulation of KLRC and Ceacam gene expression by miR-141 supports cell proliferation and metastasis in cervical cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekry, T.; Salem, M.F.; Abd-Elaziz, A.A.; Muawia, S.; Naguib, Y.M.; Khalil, H. Anticancer Properties of Selenium-Enriched Oyster Culinary-Medicinal Mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus (Agaricomycetes), in Colon Cancer In Vitro. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2022, 24, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E.-S.A.; Bassiouny, K.; Alshambky, A.A.; Khalil, H. Anticancer Properties of N,N-dibenzylasparagine as an Asparagine (Asp) analog, Using Colon Cancer Caco-2 Cell Line. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 23, 2531–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, A.; Sleem, R.; Abd-Elaziz, A.; Khalil, H. Regulation of NF-κB Expression by Thymoquinone; A Role in Regulating Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and Programmed Cell Death in Hepatic Cancer Cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 24, 3739–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bery, D.; El-Masry, S.A.; Guirgis, A.A.; Zain, A.M.; Khalil, H. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits replication of influenza A virus via restoring the host methylated genes following infection. Int. Microbiol. 2025, 28, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsattar, S.; Al-Amodi, H.S.; Kamel, H.F.; Al-Eidan, A.A.; Mahfouz, M.M.; El khashab, K.; Elshamy, A.M.; Basiouny, M.S.; Khalil, M.A.; Elawdan, K.A.; et al. Effective Targeting of Glutamine Synthetase with Amino Acid Analogs as a Novel Therapeutic Approach in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 26, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoaib, H.; Negm, A.; Abd El-Azim, A.O.; Elawdan, K.A.; Abd-ElRazik, M.; Refaai, R.; Helmy, I.; Elshamy, A.M.; Khalil, H. Ameliorative effects of Turbinaria ornata extract on hepatocellular carcinoma induced by diethylnitrosamine in-vivo. J. Mol. Histol. 2024, 55, 1225–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guirgis, S.A.; El-Halfawy, K.A.; Alalem, M.; Khalil, H. Legionellapneumophila induces methylomic changes in ten-eleven translocation to ensure bacterial reproduction in human lung epithelial cells. J. Med. Microbiol. 2023, 72, 001676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Hou, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, K.; Xiang, H.; Wan, X.; Xia, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, W.; Xu, S.; et al. Aspartate β-hydroxylase disrupts mitochondrial DNA stability and function in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogenesis 2017, 6, e362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-C.; Chang, H.-S.; Wu, Y.-C.; Cheng, W.-L.; Lin, T.-T.; Chang, H.-J.; Kuo, S.-J.; Chen, S.-T.; Liu, C.-S. Mitochondrial transplantation regulates antitumour activity, chemoresistance and mitochondrial dynamics in breast cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, E.; Gedawy, G.; Fathy, W.; Farouk, S.; El Maksoud, A.A.; Guirgis, A.A.; Khalil, H. Hsa-miR-21-mediated cell death and tumor metastases: A potential dual response during colorectal cancer development. Middle East J. Cancer 2020, 11, 483–492. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, H.; Nada, A.H.; Mahrous, H.; Hassan, A.; Rijo, P.; Ibrahim, I.A.; Mohamed, D.D.; AL-Salmi, F.A.; Mohamed, D.D.; Elmaksoud, A.I.A. Amelioration effect of 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid on methylation inhibitors in hepatocarcinogenesis -induced by diethylnitrosamine. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1206990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, E.K.; Guirgis, A.A.; Elimam, H.; Habib, D.F.; Hanna, H.; Khalil, H. Supplying rats with halfa-bar and liquorice extracts ameliorate doxorubicin-induced nephrotic syndrome. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 39, 5147–5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalem, M.; Dabous, E.; Awad, A.M.; Alalem, N.; Guirgis, A.A.; El-Masry, S.; Khalil, H. Influenza a virus regulates interferon signaling and its associated genes; MxA and STAT3 by cellular miR-141 to ensure viral replication. Virol. J. 2023, 20, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.M.; Dabous, E.; Alalem, M.; Alalem, N.; Nasr, M.E.; Elawdan, K.A.; Nasr, G.M.; Said, W.; El Khashab, K.; Basiouny, M.S.; et al. MicroRNA-141-regulated KLK10 and TNFSF-15 gene expression in hepatoblastoma cells as a novel mechanism in liver carcinogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalem, N.; Alalem, M.; Awad, A.; Elshamy, A.M.; Elalem, O.R.; Tabl, A.M.; Ebaid, M.E.; Khalil, H. A novel mechanistic study on inhibiting influenza A virus replication by a newly extracted polypeptide targeting host autophagy. Arch. Microbiol. 2025, 207, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elawdan, K.A.; Farouk, S.; Aref, S.; Shoaib, H.; El-Razik, M.A.; Abbas, N.H.; Younis, M.; Alshambky, A.A.; Khalil, H. Association of vitamin B12/ferritin deficiency in cancer patients with methylomic changes at promotors of TET methylcytosine dioxygenases. Biomark. Med. 2022, 16, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeffer, I.; Brewitz, L.; Krojer, T.; Jensen, S.A.; Kochan, G.T.; Kershaw, N.J.; Hewitson, K.S.; McNeill, L.A.; Kramer, H.; Münzel, M.; et al. Aspartate/asparagine-β-hydroxylase crystal structures reveal an unexpected epidermal growth factor-like domain substrate disulfide pattern. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwal, M.; Smahel, M.; Olsen, M.; Smahelova, J.; Tachezy, R. Aspartate β-hydroxylase as a target for cancer therapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radogna, F.; Albertini, M.C.; De Nicola, M.; Diederich, M.; Bejarano, I.; Ghibelli, L. Melatonin promotes Bax sequestration to mitochondria reducing cell susceptibility to apoptosis via the lipoxygenase metabolite 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid. Mitochondrion 2015, 21, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.C. Mitochondria and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhmeida, A.; Assidi, M.; Al-Maghrabi, J.; Dallol, A.; Sibiany, A.; Al-Ahwal, M.; Chaudhary, A.; Abuzenadah, A.; Al-Qahtani, M. Membranous or Cytoplasmic HER2 Expression in Colorectal Carcinoma: Evaluation of Prognostic Value Using Both IHC & BDISH. Cancer Investig. 2018, 36, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Di Minno, A.; Santarcangelo, C.; Khan, H.; Daglia, M. Improvement of Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction by β-Caryophyllene: A Focus on the Nervous System. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, S.W.G.; Green, D.R. Mitochondrial Regulation of Cell Death. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a008706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, C.; Delivani, P.; Cullen, S.P.; Martin, S.J. Bax- or Bak-Induced Mitochondrial Fission Can Be Uncoupled from Cytochrome C Release. Mol. Cell 2008, 31, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lartigue, L.; Kushnareva, Y.; Seong, Y.; Lin, H.; Faustin, B.; Newmeyer, D.D. Caspase-independent Mitochondrial Cell Death Results from Loss of Respiration, Not Cytotoxic Protein Release. Mol. Biol. Cell 2009, 20, 4871–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Description | Primer Sequences 5′-3′ |

|---|---|

| Ras sense | ATACAGCTAATTCAGAATCATTT |

| Ras antisense | CTATAATGGTGAATATCTTCAAA |

| Raf-1 sense | TTTCCTGGATCATGTTCCCCT |

| Raf-1 antisense | ACTTTGGTGCTACAGTGCTCA |

| NFkB1-sense | GAAATTCCTGATCCAGACAAAAAC |

| NF-kB1 antisense | ATCACTTCAATGGCCTCTGTGTAG |

| ERK1 sense | TGTTATAGGCATCCGAGACATCCT |

| ERK1 antisense | CCATGAGGTCCTGAACAATGTAAAC |

| ASPH sense | AAGGCGGACTCTCAGGAACT |

| ASPH antisense | AATCTCCATCACCATCAGCAT |

| ND-1 senses | ATACAACTACGCAAAGGCCCCA |

| ND-1 antisense | AATAGGAGGCCTAGGTTGAGGT |

| D-loop sense | TTGATTCCTGCCTCATCCTAT |

| D-loop antisense | GTCTGTGTGGAAAGTGGCTGT |

| β-actin sense | GATGACCCAGATCATGTTTGAG |

| β-actin antisense | AGGGCATACCCCTCGTAGAT |

| GAPDH-sense | TGGCATTGTGGAAGGGCTCA |

| GAPDH-antisense | TGGATGCAGGGATGATGTTCT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tabl, A.M.; Ebeid, M.E.; Ali, Y.B.M.; Elawdan, K.A.; Alalem, M.; Al-Eidan, A.A.; Alalem, N.; Mansour, A.S.; Awad, A.M.; El-Madawy, E.A.; et al. Nanomodified Nexavar Enhances Efficacy in Caco-2 Cells via Targeting Aspartate β-Hydroxylase-Driven Mitochondrial Cell Death. Immuno 2026, 6, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/immuno6010005

Tabl AM, Ebeid ME, Ali YBM, Elawdan KA, Alalem M, Al-Eidan AA, Alalem N, Mansour AS, Awad AM, El-Madawy EA, et al. Nanomodified Nexavar Enhances Efficacy in Caco-2 Cells via Targeting Aspartate β-Hydroxylase-Driven Mitochondrial Cell Death. Immuno. 2026; 6(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/immuno6010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleTabl, Ahmed M., Mohamed E. Ebeid, Yasser B. M. Ali, Khaled A. Elawdan, Mai Alalem, Ahood A. Al-Eidan, Nedaa Alalem, Ahmed S. Mansour, Ahamed M. Awad, Eman A. El-Madawy, and et al. 2026. "Nanomodified Nexavar Enhances Efficacy in Caco-2 Cells via Targeting Aspartate β-Hydroxylase-Driven Mitochondrial Cell Death" Immuno 6, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/immuno6010005

APA StyleTabl, A. M., Ebeid, M. E., Ali, Y. B. M., Elawdan, K. A., Alalem, M., Al-Eidan, A. A., Alalem, N., Mansour, A. S., Awad, A. M., El-Madawy, E. A., Elbuckley, S. A., Refaai, R., Elshamy, A. M., & Khalil, H. (2026). Nanomodified Nexavar Enhances Efficacy in Caco-2 Cells via Targeting Aspartate β-Hydroxylase-Driven Mitochondrial Cell Death. Immuno, 6(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/immuno6010005