Cognitive and Psychosocial Recovery in Schizophrenia: Evidence from a Case Study on Integrated Rehabilitation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Description

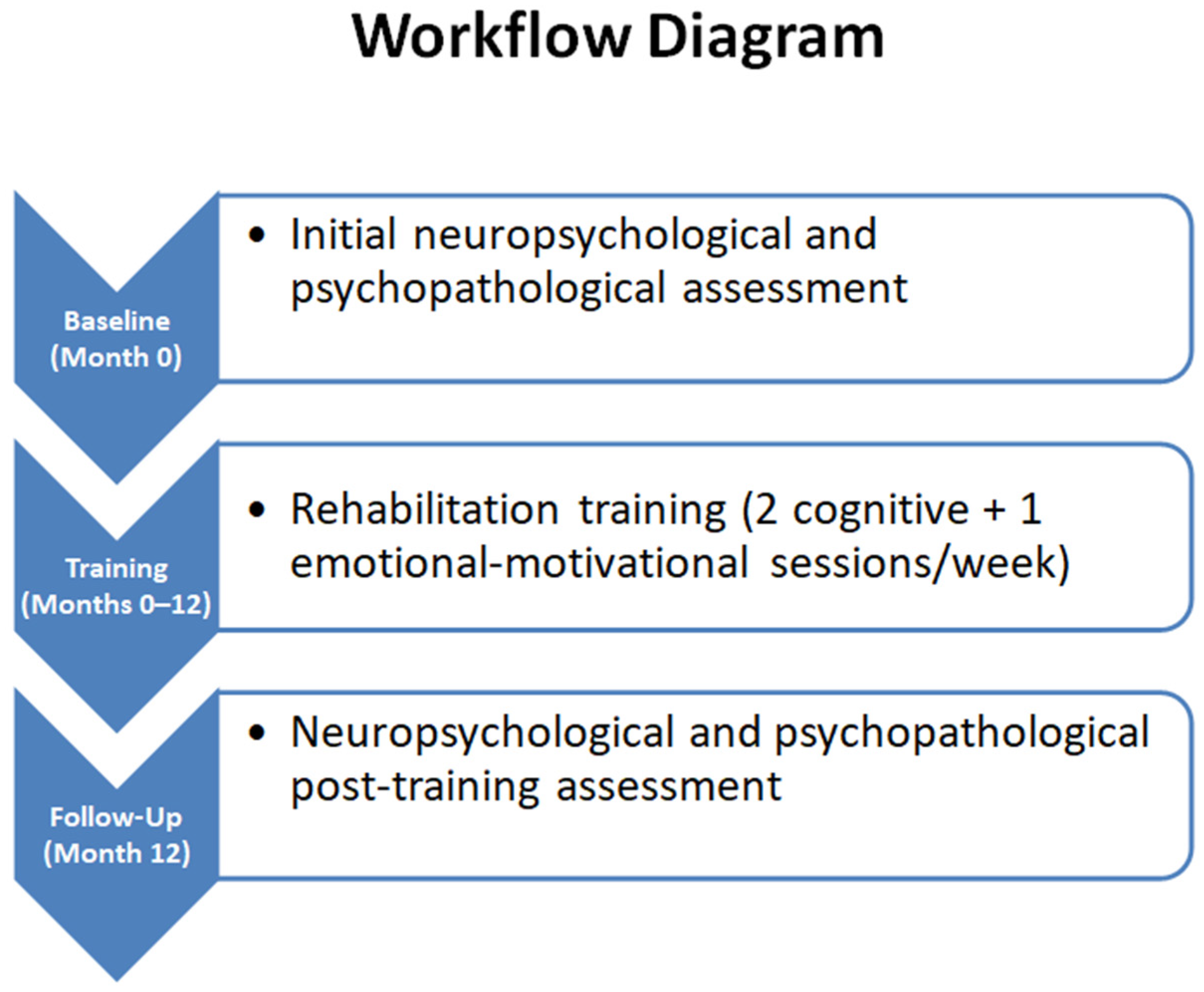

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rahman, T.; Lauriello, J. Schizophrenia: An Overview. Focus 2016, 14, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correll, C.U.; Schooler, N.R. Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Review and Clinical Guide for Recognition, Assessment, and Treatment. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasso, C.; Bellino, S.; Bozzatello, P.; Montemagni, C.; Rocca, P. Real-life functioning and duration of illness in schizophrenia: A mediation analysis. Heliyon 2024, 11, e41332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantala, M.J.; Luoto, S.; Borráz-León, J.I.; Krams, I. Schizophrenia: The new etiological synthesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 142, 104894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, R.; Liao, J.; Xiong, X.; Xia, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Zhao, F.; Zhuo, L.; Li, H. Meta-analysis of structural and functional brain abnormalities in early-onset schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1465758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.D.; Bosia, M.; Cavallaro, R.; Howes, O.D.; Kahn, R.S.; Leucht, S.; Müller, D.R.; Penadés, R.; Vita, A. Cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia: An expert group paper on the current state of the art. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 2022, 29, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, R.A.; Keefe, R.S.E.; McGuire, P.K. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: Aetiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 1902–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, W.J.; Abd Hamid, A.I.; Abdullah, J.M. Working Memory From the Psychological and Neurosciences Perspectives: A Review. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamata, Y.; Ohi, K.; Ito, S.; Hasegawa, N.; Yasuda, Y.; Fujimoto, M.; Yamamori, H.; Fukumoto, K.; Kodaka, F.; Matsumoto, J.; et al. Relationships between clinician adherence to guideline-recommended treatment and memory function in patients with schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2025, 185, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thibaudeau, E.; Bowie, C.R.; Montreuil, T.; Baer, L.; Lecomte, T.; Joober, R.; Abdel-Baki, A.; Jarvis, G.E.; Margolese, H.C.; De Benedictis, L.; et al. Acceptability, engagement, and efficacy of cognitive remediation for cognitive outcomes in young adults with first-episode psychosis and social anxiety: A randomized-controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 342, 116243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaker, P.H.; Pattison, M.L.; Leonhardt, B.L.; Phelps, S.; Vohs, J.L. Insight in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: Relationship with behavior, mood and perceived quality of life, underlying causes and emerging treatments. World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. (WPA) 2018, 17, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoupa, E.; Bogiatzidou, O.; Siokas, V.; Liampas, I.; Tzeferakos, G.; Mavreas, V.; Stylianidis, S.; Dardiotis, E. Cognitive Rehabilitation in Schizophrenia-Associated Cognitive Impairment: A Review. Neurol. Int. 2022, 15, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wykes, T.; Huddy, V.; Cellard, C.; McGurk, S.R.; Czobor, P. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: Methodology and effect sizes. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, A.; Barlati, S.; Ceraso, A.; Nibbio, G.; Ariu, C.; Deste, G.; Wykes, T. Effectiveness, key elements, and moderators of cognitive rehabilitation response for schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.P.; Ventura, J.; Subotnik, K.L.; Nuechterlein, K.H. Intrinsic motivation predicts cognitive and functional gains during coordinated specialty care for first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2024, 266, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, A.; Barlati, S.; Ceraso, A.; Nibbio, G.; Durante, F.; Facchi, M.; Deste, G.; Wykes, T. Durability of Effects of Cognitive Remediation on Cognition and Psychosocial Functioning in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Am. J. Psychiatry 2024, 181, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbe, D.E. The Therapeutic Alliance: The Fundamental Element of Psychotherapy. Focus 2018, 16, 402–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnier, J.J.; Kienle, G.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; Sox, H.; Riley, D. The CARE Guidelines: Consensus-based Clinical Case Reporting Guideline Development. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2013, 2, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I.H.; Manly, T.; Andrade, J.; Baddeley, B.T.; Yiend, J. ‘Oops!’: Performance correlates of everyday attentional failures in traumatic brain injured and normal subjects. Neuropsychologia 1997, 35, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicerone, K.D.; Dahlberg, C.; Kalmar, K.; Langenbahn, D.M.; Malec, J.F.; Bergquist, T.F.; Felicetti, T.; Giacino, J.T.; Harley, J.P.; Harrington, D.E.; et al. Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Recommendations for clinical practice. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000, 81, 1596–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabbatore, I.; Sacco, K.; Angeleri, R.; Zettin, M.; Bara, B.G.; Bosco, F.M. Cognitive Pragmatic Treatment: A Rehabilitative Program for Traumatic Brain Injury Individuals. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015, 30, E14–E28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, N.S.; Truax, P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, J.; Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N.; Sánchez, P.; Uriarte, J.J.; Elizagarate, E.; Gutierrez, M.; Ojeda, N. Mechanisms of functional improvement through cognitive rehabilitation in schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 101, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilicoglu, M.F.V.; Lundin, N.B.; Angers, K.; Moe, A.M. Narrative-Derived Indices of Metacognition among People with Schizophrenia: Associations with Self-Reported and Performance-Based Social Functioning. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argento, O.; Piacentini, C.; Bossa, M.; Caltagirone, C.; Santamato, A.; Saraceni, V.; Nocentini, U. Motor, cognitive, and combined rehabilitation approaches on MS patients’ cognitive impairment. Neurol. Sci. 2023, 44, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pijnenborg, G.H.M.; Larabi, D.I.; Xu, P.; Hasson-Ohayon, I.; de Vos, A.E.; Ćurčić-Blake, B.; Aleman, A.; Van der Meer, L. Brain areas associated with clinical and cognitive insight in psychotic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 116, 301–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, X.; Dai, Y.; Tang, J.; Huang, Y.; Hu, R.; Lin, Y. Cognitive rehabilitation in schizophrenia research: A bibliometric and visualization analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1509539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventriglio, A.; Gentile, A.; Bonfitto, I.; Stella, E.; Mari, M.; Steardo, L.; Bellomo, A. Suicide in the Early Stage of Schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, E.P.; Oquendo, M.A. Suicide Risk Assessment and Prevention: Challenges and Opportunities. Focus 2020, 18, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cates, A.N.; Catone, G.; Marwaha, S.; Bebbington, P.; Humpston, C.S.; Broome, M.R. Self-harm, suicidal ideation, and the positive symptoms of psychosis: Cross-sectional and prospective data from a national household survey. Schizophr. Res. 2021, 233, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlborg, A.; Jokinen, J.; Nordström, A.L.; Jönsson, E.G.; Nordström, P. CSF 5-HIAA, attempted suicide and suicide risk in schizophrenia spectrum psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2009, 112, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, H.Y.; Alphs, L.; Green, A.I.; Altamura, A.C.; Anand, R.; Bertoldi, A.; Bourgeois, M.; Chouinard, G.; Islam, M.Z.; Kane, J.; et al. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT). Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuechterlein, K.H.; Nasrallah, H.; Velligan, D. Measuring Cognitive Impairments Associated With Schizophrenia in Clinical Practice: Overview of Current Challenges and Future Opportunities. Schizophr. Bull. 2025, 51, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Yue, S.; Duan, M.; Yao, D.; Luo, C. Psychosocial intervention for schizophrenia. Brain-Appar. Commun. A J. Bacomics 2023, 2, 2178266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test | Description |

|---|---|

| Attention Matrices | Test evaluating selective and sustained attention. The patient must identify and discriminate visual stimuli among distractors, measuring processing speed, concentration, and resistance to distraction. |

| Raven’s Progressive Matrices | Non-verbal tool for assessing logical reasoning and problem-solving abilities. The subject completes visual patterns of increasing difficulty, measuring abstraction and analytical thinking. |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) | Assesses attention, processing speed, and cognitive flexibility. Part A involves connecting numbers sequentially; Part B alternates numbers and letters, also stimulating planning and executive control. |

| Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test | Measures short- and long-term verbal memory. The patient listens to a list of words and must recall them immediately and after a delay, evaluating learning, consolidation, and memory retrieval. |

| Verbal Fluency Test | Evaluates verbal production and executive functions. Includes phonological fluency (words starting with a letter) and semantic fluency (category of objects), measuring speed, planning, inhibitory control, and language skills. |

| Digit Span | Tests working memory and attention. The subject repeats sequences of numbers in forward and backward order. The backward version requires active manipulation of information, assessing retention and processing capacity. |

| Token Test | Examines language comprehension and auditory memory. The patient must follow increasingly complex instructions using tokens of different colors and shapes, evaluating language, attention, and ability to follow complex commands. |

| Insight Test | Clinical tool to assess the patient’s awareness of their cognitive and clinical state, useful for identifying distortions in self-awareness and metacognition. |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) | 21-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure depression severity according to DSM-IV criteria. Examines mood, loss of pleasure, guilt, suicidal thoughts, energy, appetite, and sleep. |

| Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) | 14-item clinical scale assessing severity of anxiety symptoms. Evaluates psychological symptoms (anxiety, fear, tension) and somatic symptoms (muscular, sensory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal), providing a quantitative measure of anxiety. |

| Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2) | 567-item true/false personality inventory widely used for psychological assessment and diagnosis of psychopathological disorders. Includes 10 clinical scales and 8 validity scales, providing a detailed profile of the subject’s psychological and behavioral characteristics. |

| Cognitive Function | Objectives | Intervention Modalities |

|---|---|---|

| Attention | Reduce the impact of distracting stimuli; improve target stimulus identification | Paper-and-pencil and verbal exercises, auditory and visuospatial exploration, management of complex tasks; progressive increase in task complexity |

| Short-term memory | Improve the ability to memorize and recall information over short intervals | Computerized exercises requiring the patient to remember and reproduce words or numbers after 15 min intervals |

| Long-term memory | Consolidate information and strengthen episodic memory | Oral and written narrative exercises, focusing on personal events and clinical history |

| Executive functions | Recover pragmatic and social skills; improve problem-solving and metacognition | Working memory and metacognition exercises; relearning the steps to complete goal-directed tasks (goal setting, subgoal organization, result monitoring) |

| Emotional–motivational support | Enhance relational skills, motivation, and emotional well-being | Individual or group sessions, discussion, and strategies for emotional regulation |

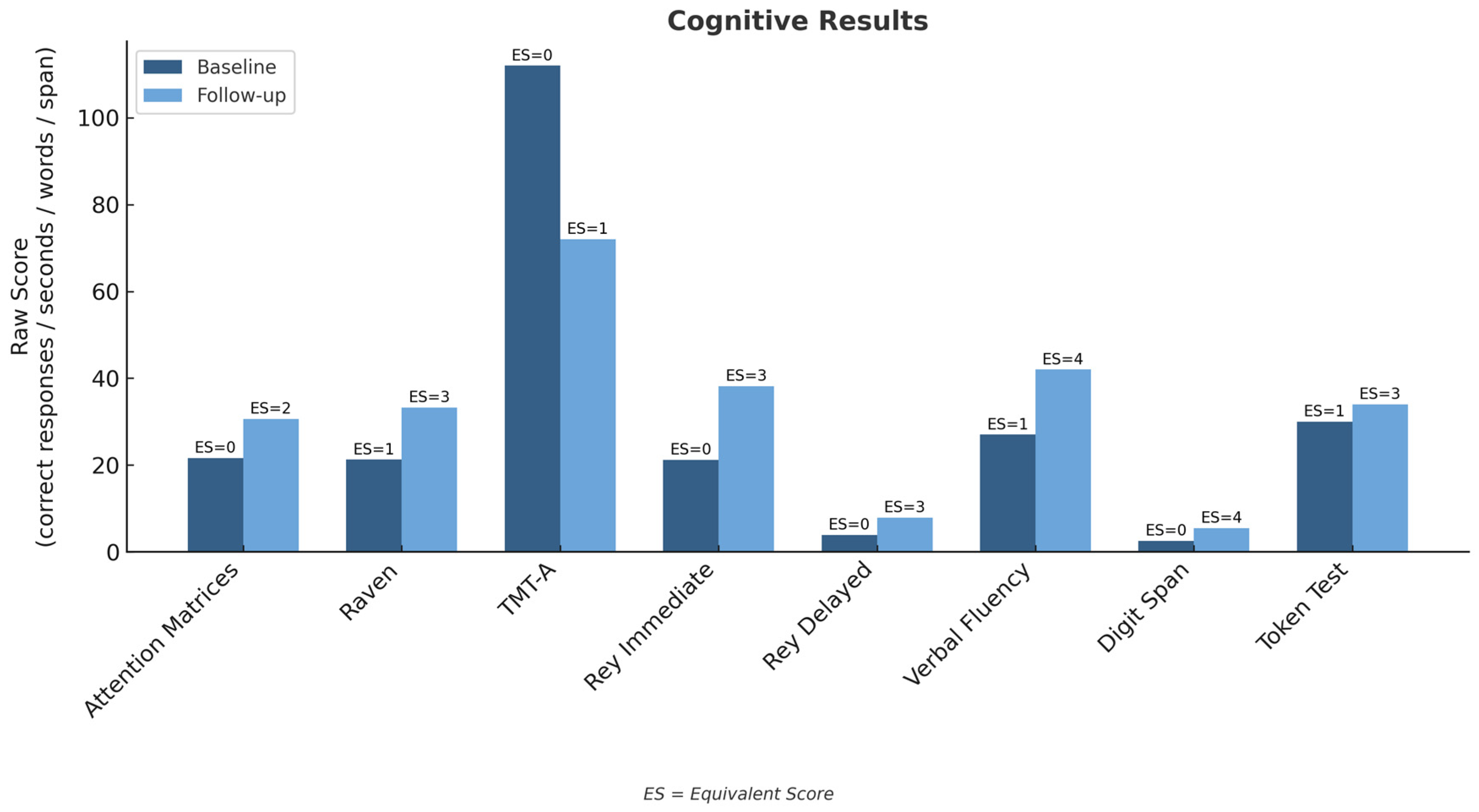

| Test | Baseline (Raw; Unit) | Baseline (Std.) | Follow-Up (Raw; Unit) | Follow-Up (Std.) | Cut-Off/Threshold | RCI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Matrices | 21.6 (responses) | ES = 0 | 30.6 (responses) | ES = 2 | ES < 2 = deficit | +2.45 | 0.014 |

| Raven’s Progressive Matrices | 21.25 | ES = 1 | 33.25 | ES = 3 | ES < 2 = deficit | +2.18 | 0.029 |

| Trail Making Test—A | 112 s | ES = 0 | 72 s | ES = 1 | Time > 93 s = deficit | +1.97 | 0.049 |

| Trail Making Test—B | — | — | 243 s | ES = 1 | Time > 282 s = deficit | n/a | n/a |

| Trail Making Test B–A | — | — | 171 s | ES = 1 | Time > 187 s = deficit | n/a | n/a |

| Rey Word List—Immediate | 21.2 (words) | ES = 0 | 38.2 (words) | ES = 3 | <28.5 = deficit | +2.80 | 0.05 |

| Rey Word List—Delayed | 3.9 (words) | ES = 0 | 7.9 (words) | ES = 3 | <4.7 = deficit | +2.42 | 0.016 |

| Verbal Fluency (phon./sem.) | 27 (words) | ES = 1 | 42 (words) | ES = 4 | <25 = deficit | +2.10 | 0.036 |

| Digit Span (total) | 2.5 (span) | ES = 0 | 5.5 (span) | ES = 4 | <3.75 = deficit | +2.85 | 0.004 |

| BDI-II | 45 (total) | — | 27 (total) | — | 0–13 minimal; 14–19 mild; 20–28 moderate; ≥29 severe | +2.10 | 0.036 |

| HAM-A | 25 (total) | — | 17 (total) | — | 0–17 mild; 18–24 moderate; 25–30 severe | +1.95 | 0.052 |

| Insight Test | 1 | — | 6 | — | Scale 0–8 (Absent → Present) | +2.20 | 0.028 |

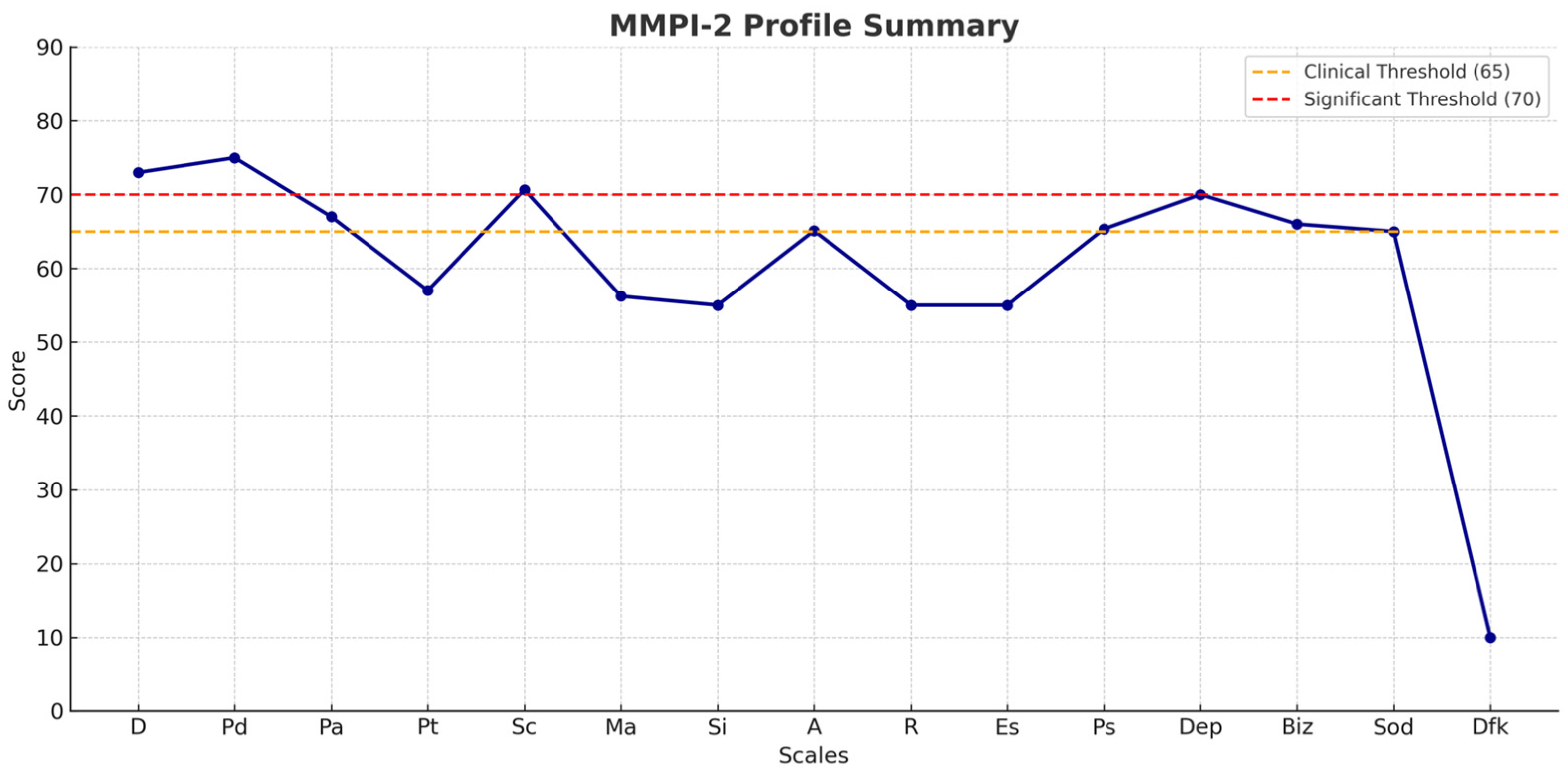

| MMPI-2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Basic Clinical Scales | Additional Scales | Content Scales |

| D (Depression) P = 73 | A (Anxiety) P = 65.10 | Dep (Presence of depressive thoughts) P = 70 |

| Pd (Psychopathic deviation) P = 75 | R (Repression) P = 55 | Biz (Bizzarries) P = 66 |

| Pa (Paranoia) P = 67 | Es (Ego Strength) P = 55 | Sod (Social discomfort) P = 65 |

| Pt (Psychasthenia) P = 57 | Ps (Post-traumatic stress) P = 65.34 | Dfk (Difficulties in monitoring and defense) DFK = 10 |

| Sc (Schizophrenia) P = 70.67 | ||

| Ma (Mania) P = 56.22 | ||

| Si (Social Introversion) P = 55 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cappadona, I.; Pagano, M.; Anselmo, A.; Cardile, D.; De Luca, R.; Todaro, A.; Calabrò, R.S.; Corallo, F. Cognitive and Psychosocial Recovery in Schizophrenia: Evidence from a Case Study on Integrated Rehabilitation. Psychiatry Int. 2026, 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010006

Cappadona I, Pagano M, Anselmo A, Cardile D, De Luca R, Todaro A, Calabrò RS, Corallo F. Cognitive and Psychosocial Recovery in Schizophrenia: Evidence from a Case Study on Integrated Rehabilitation. Psychiatry International. 2026; 7(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleCappadona, Irene, Maria Pagano, Anna Anselmo, Davide Cardile, Rosaria De Luca, Antonino Todaro, Rocco Salvatore Calabrò, and Francesco Corallo. 2026. "Cognitive and Psychosocial Recovery in Schizophrenia: Evidence from a Case Study on Integrated Rehabilitation" Psychiatry International 7, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010006

APA StyleCappadona, I., Pagano, M., Anselmo, A., Cardile, D., De Luca, R., Todaro, A., Calabrò, R. S., & Corallo, F. (2026). Cognitive and Psychosocial Recovery in Schizophrenia: Evidence from a Case Study on Integrated Rehabilitation. Psychiatry International, 7(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010006