Associations Between Young Adult Emotional Support Derived from Social Media, Personality Structure, and Anxiety

Abstract

1. Background

2. Method

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Anxiety

2.2.2. Social Media Emotional Support

2.2.3. Personality

2.2.4. Gender

2.2.5. Age

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whiteford, H.A.; Degenhardt, L.; Rehm, J.; Baxter, A.J.; Ferrari, A.J.; Erskine, H.E.; Charlson, F.J.; Norman, R.E.; Flaxman, A.D.; Johns, N.; et al. Global Burden of Disease Attributable to Mental and Substance Use Disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013, 382, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.R.; McGee, R.E.; Druss, B.G. Mortality in Mental Disorders and Global Disease Burden Implications: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegria, M.; Jackson, J.S.; Kessler, R.C.; Takeuchi, D. Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES), 2001–2003 [United States]; ICPSR Data Holdings: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Il Shin, J.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Age at Onset of Mental Disorders Worldwide: Large-Scale Meta-Analysis of 192 Epidemiological Studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, G.; Wilhelm, K.; Mitchell, P.; Austin, M.-P.; Roussos, J.; Gladstone, G. The Influence of Anxiety as a Risk to Early Onset Major Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 1999, 52, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lew, B.; Huen, J.; Yu, P.; Yuan, L.; Wang, D.-F.; Ping, F.; Abu Talib, M.; Lester, D.; Jia, C.-X. Associations between Depression, Anxiety, Stress, Hopelessness, Subjective Well-Being, Coping Styles and Suicide in Chinese University Students. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, J.M.; Alviña, K. The Role of Inflammation and the Gut Microbiome in Depression and Anxiety. J. Neurosci. Res. 2019, 97, 1223–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellappa, S.L.; Aeschbach, D. Sleep and Anxiety: From Mechanisms to Interventions. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 61, 101583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, M.F.P.; Mercante, J.P.P.; Tobo, P.R.; Kamei, H.; Bigal, M.E. Anxiety and Depression Symptoms and Migraine: A Symptom-Based Approach Research. J. Headache Pain 2017, 18, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.F.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Samma, M. Sustainable Work Performance: The Roles of Workplace Vi-olence and Occupational Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, I.; Catling, J.C. The Influence of Perfectionism, Self-Esteem and Resilience on Young People’s Mental Health. J. Psychol. 2022, 156, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa-Camacho, F.J.; Romero-Limón, O.M.; Ibarrola-Peña, J.C.; Almanza-Mena, Y.L.; Pintor-Belmontes, K.J.; Sánchez-López, V.A.; Chejfec-Ciociano, J.M.; Guzmán-Ramírez, B.G.; Sapién-Fernández, J.H.; Guz-mán-Ruvalcaba, M.J.; et al. Depression, Anxiety, and Academic Performance in COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Roberts, J.E. Social Anxiety, Depressive Symptoms, and Post-Event Rumination: Affective Consequences and Social Contextual Influences. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007, 21, 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, R.D.; Weinberger, A.H.; Kim, J.H.; Wu, M.; Galea, S. Trends in Anxiety among Adults in the United States, 2008–2018: Rapid Increases among Young Adults. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 130, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. APA Dictionary of Psychology. 2022. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/emotional-support (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Huang, L.; Picart, J.; Gillan, D. Toward a Generalized Model of Human Emotional Attachment. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 2021, 22, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Kendler, K.S.; Heath, A.; Neale, M.C.; Eaves, L.J. Social Support, Depressed Mood, and Adjustment to Stress: A Genetic Epidemiologic Investigation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 62, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E. Social Support: A Review. In The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 190–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. Mechanisms Linking Social Ties and Support to Physical and Mental Health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, A.; Krnjacki, L.; LaMontagne, A.D. Age and Gender Differences in the Influence of Social Support on Mental Health: A Longitudinal Fixed-Effects Analysis Using 13 Annual Waves of the HILDA Cohort. Public Health 2016, 140, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovier, P.A.; Chamot, E.; Perneger, T.V. Perceived Stress, Internal Resources, and Social Support as Deter-Minants of Mental Health Among Young Adults. Qual. Life Res. 2004, 13, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cai, L.; Qian, J.; Peng, J. Social Support Moderates Stress Effects on Depression. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2014, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornblith, A.B.; Herndon, J.E.; Zuckerman, E.; Viscoli, C.M.; Horwitz, R.I.; Cooper, M.R.; Harris, L.; Tkaczuk, K.H.; Perry, M.C.; Budman, D.; et al. Social Support as a Buffer to the Psychological Impact of Stressful Life Events in Women with Breast Cancer. Cancer 2001, 91, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Escobar-Viera, C.G.; Switzer, G.E.; Primack, B.A.; Choukas-Bradley, S. Emotional Support from Social Media and Face-to-Face Relationships: Associations with Depression Risk Among Young Adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandes, M.; Bienvenu, O.J. Personality and Anxiety Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2006, 8, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, A.M. Construction of Anxiety and Dimensional Personality Model in College Students. Psychol. Rep. 2013, 112, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakulinen, C.; Jokela, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Elovainio, M. Personality Traits and Mental Disorders. In The Cambridge Handbook of Personality Psychology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, H.; Ebrahimi, O.V.; Hoffart, A.; Johnson, S.U. Trait Versus State Predictors of Emotional Distress Symptoms. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2022, 210, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, L. The Mediating Role of Resilience in the Relationship Between Big Five Personality and Anxiety Among Chinese Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikčević, A.V.; Marino, C.; Kolubinski, D.C.; Leach, D.; Spada, M.M. Modelling the Contribution of the Big Five Personality Traits, Health Anxiety, and COVID-19 Psychological Distress to Generalised Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barańczuk, U. The Five Factor Model of Personality and Social Support: A Meta-Analysis. J. Res. Pers. 2019, 81, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J. (Ed.) Neurotechnology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Dew, M.A.; Escobar-Viera, C.G.; Primack, B.A. Social Media Use and Depression and Anxiety Symptoms: A Cluster Analysis. Am. J. Health Behav. 2018, 42, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, J.L.; Agas, J.M.; Lee, M.; Pan, J.L.; Buttenheim, A.M. Comparison of Online Survey Recruitment Platforms for Hard-to-Reach Pregnant Smoking Populations: Feasibility Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7, e8071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Yu, Z.; Wu, J.; Kean, J.; Monahan, P.O. Operating Characteristics of PROMIS Four-Item De-pression and Anxiety Scales in Primary Care Patients with Chronic Pain. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 1892–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, E. Anxiety. Nurs. Stand. 2016, 30, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkonis, P.A.; Choi, S.W.; Reise, S.P.; Stover, A.M.; Riley, W.T.; Cella, D. Item Banks for Measuring Emotional Distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): Depression, Anxiety, and Anger. Assessment 2011, 18, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, D.; Choi, S.W.; Condon, D.M.; Schalet, B.; Hays, R.D.; Rothrock, N.E.; Yount, S.; Cook, K.F.; Gershon, R.C.; Amtmann, D.; et al. PROMIS® Adult Health Profiles: Efficient Short-Form Measures of Seven Health Domains. Value Health 2019, 22, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B. A Very Brief Measure of the Big-Five Personality Domains. J. Res. Pers. 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, R.A.; Cao, C.; Primack, B.A. Associations Between Social Media Use, Personality Structure, and Development of Depression. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2022, 10, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppel, G.; Wickens, T.D. Design and Analysis: A Researcher’s Handbook; Pearson Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.Y.; Hancock, J.T. Social Media Mindsets: A New Approach to Understanding Social Media Use and Psychological Well-Being. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2023, 29, zmad048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.; Phillips, C.V.; Rodriguez, A.; Young, A.R.; Ramdass, J.V. Relationships Matter! Social Safeness and Self-Disclosure May Influence the Relationship Between Perceived Social Support and Well-Being for In-Person and Online Relationships. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 52, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; Ibáñez, I.; Bethencourt, J.M.; Marrero, R.; Carballeira, M. Structural Gender Differences in Perceived Social Support. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2003, 35, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P.; Matos, P.M.; Silva, E.R.; Silva, J.; Silva, E.; Sales, C.M.D. Distress Facing Increased Genetic Risk of Cancer: The Role of Social Support and Emotional Suppression. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 2436–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.S. Neuroticism and Health as Individuals Age. Personal. Disord. Theory Res. Treat. 2019, 10, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asselmann, E.; Specht, J. Changes in Happiness, Sadness, Anxiety, and Anger around Romantic Relationship Events. Emotion 2023, 23, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W.; Lejuez, C.; Krueger, R.F.; Richards, J.M.; Hill, P.L. What Is Conscientiousness and How Can It Be Assessed? Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 1315–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SMES | - | ||||||||

| 2. Anxiety | 0.17 ** | - | |||||||

| 3. Age | −0.08 ** | −0.10 ** | - | ||||||

| 4. Gender | 0.06 * | 0.11 ** | −0.06 * | - | |||||

| 5. Openness | 0.06 * | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.02 | - | ||||

| 6. Conscientious. | −0.06 * | −0.22 ** | 0.07 ** | 0.04 | 0.10 ** | - | |||

| 7. Extraversion | 0.14 ** | −0.10 ** | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.11 ** | - | ||

| 8. Agreeableness | 0.09 ** | −0.15 * | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.16 ** | 0.12 ** | - | |

| 9. Neuroticism | 0.04 * | 0.44 * | −0.08 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.02 | −0.22 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.22 ** | - |

| Study Variables | df | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Openness | 1 | 4.69 | 0.0046 |

| Conscientiousness | 1 | 9.19 | 0.0025 |

| Extraversion | 1 | 20.72 | <0.0001 |

| Agreeableness | 1 | 18.73 | <0.0001 |

| Neuroticism | 1 | 0.35 | 0.5536 |

| Study Variables | SMES (Mean) | SMES (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Openness | ||

| Yes | 10.58 | 4.74 |

| No | 10.17 | 4.74 |

| Conscientiousness | ||

| Yes | 10.16 | 4.73 |

| No | 10.78 | 4.75 |

| Extraversion | ||

| Yes | 11.01 | 4.72 |

| No | 10.07 | 4.73 |

| Agreeableness | ||

| Yes | 10.73 | 4.84 |

| No | 9.89 | 4.56 |

| Neuroticism | ||

| Yes | 10.44 | 4.56 |

| No | 10.32 | 4.85 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 10.64 | 4.68 |

| Male | 10.09 | 4.79 |

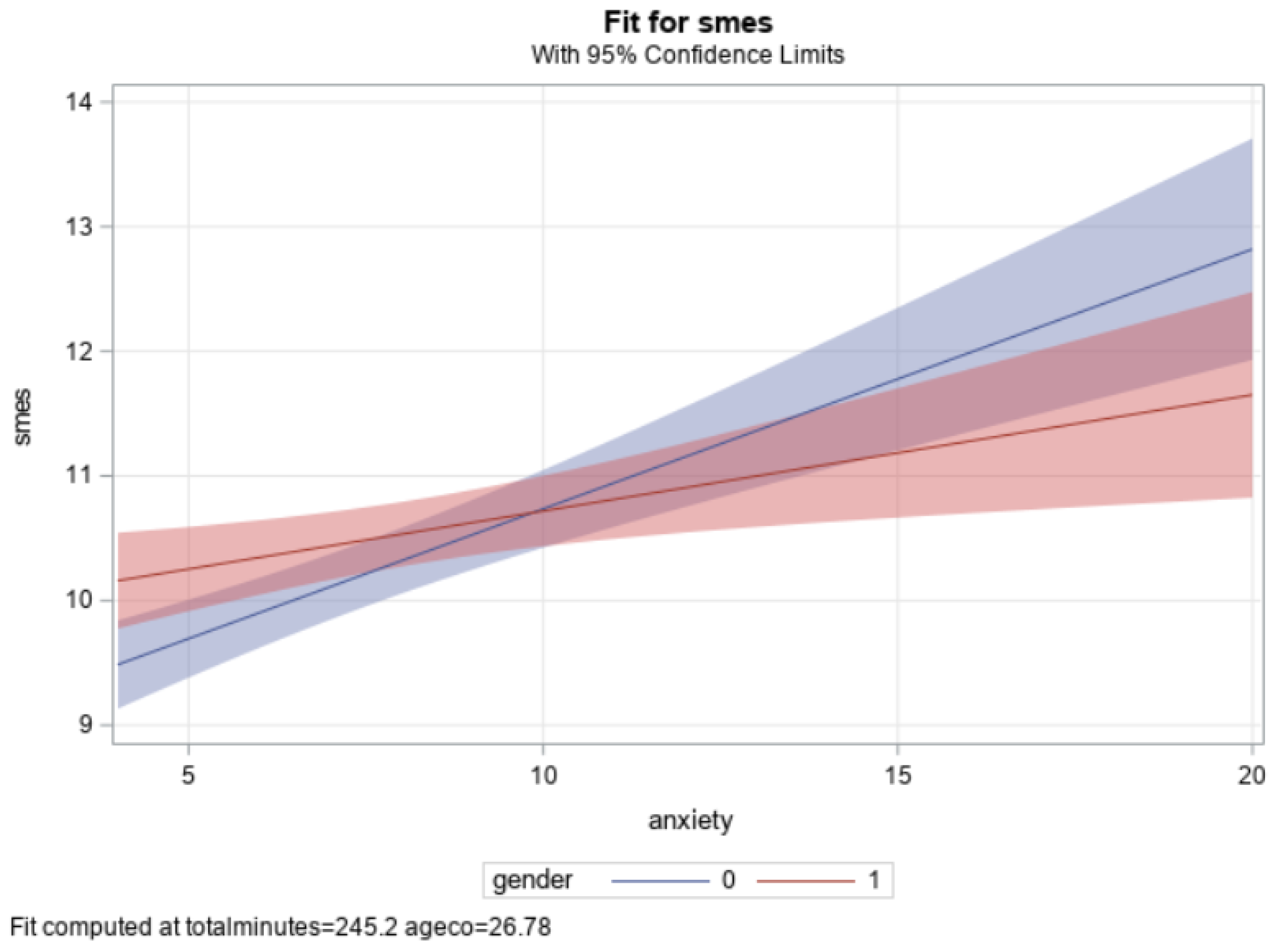

| Study Variables | Coefficients | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | −0.13 | −0.55 | 0.58 |

| Social Media (in minutes) | 0.001 | 10.81 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 1.13 | 2.67 | 0.01 |

| Age | −0.19 | −2.6 | 0.01 |

| Anxiety * Gender | −0.12 | −2.39 | 0.02 |

| Anxiety * Age | 0.01 | 1.49 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Merrill, R.A.; Cao, C. Associations Between Young Adult Emotional Support Derived from Social Media, Personality Structure, and Anxiety. Psychiatry Int. 2026, 7, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010018

Merrill RA, Cao C. Associations Between Young Adult Emotional Support Derived from Social Media, Personality Structure, and Anxiety. Psychiatry International. 2026; 7(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerrill, Renae A., and Chunhua Cao. 2026. "Associations Between Young Adult Emotional Support Derived from Social Media, Personality Structure, and Anxiety" Psychiatry International 7, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010018

APA StyleMerrill, R. A., & Cao, C. (2026). Associations Between Young Adult Emotional Support Derived from Social Media, Personality Structure, and Anxiety. Psychiatry International, 7(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010018