Long-Term Consequences of Combat Stress in Afghan War Veterans: Comorbidity of PTSD and Physical and Mental Health Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Methodological Basis

2.3.1. The Mississippi PTSD Scale

2.3.2. The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R)

2.3.3. The Spielberger–Khanin Questionnaire

2.3.4. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

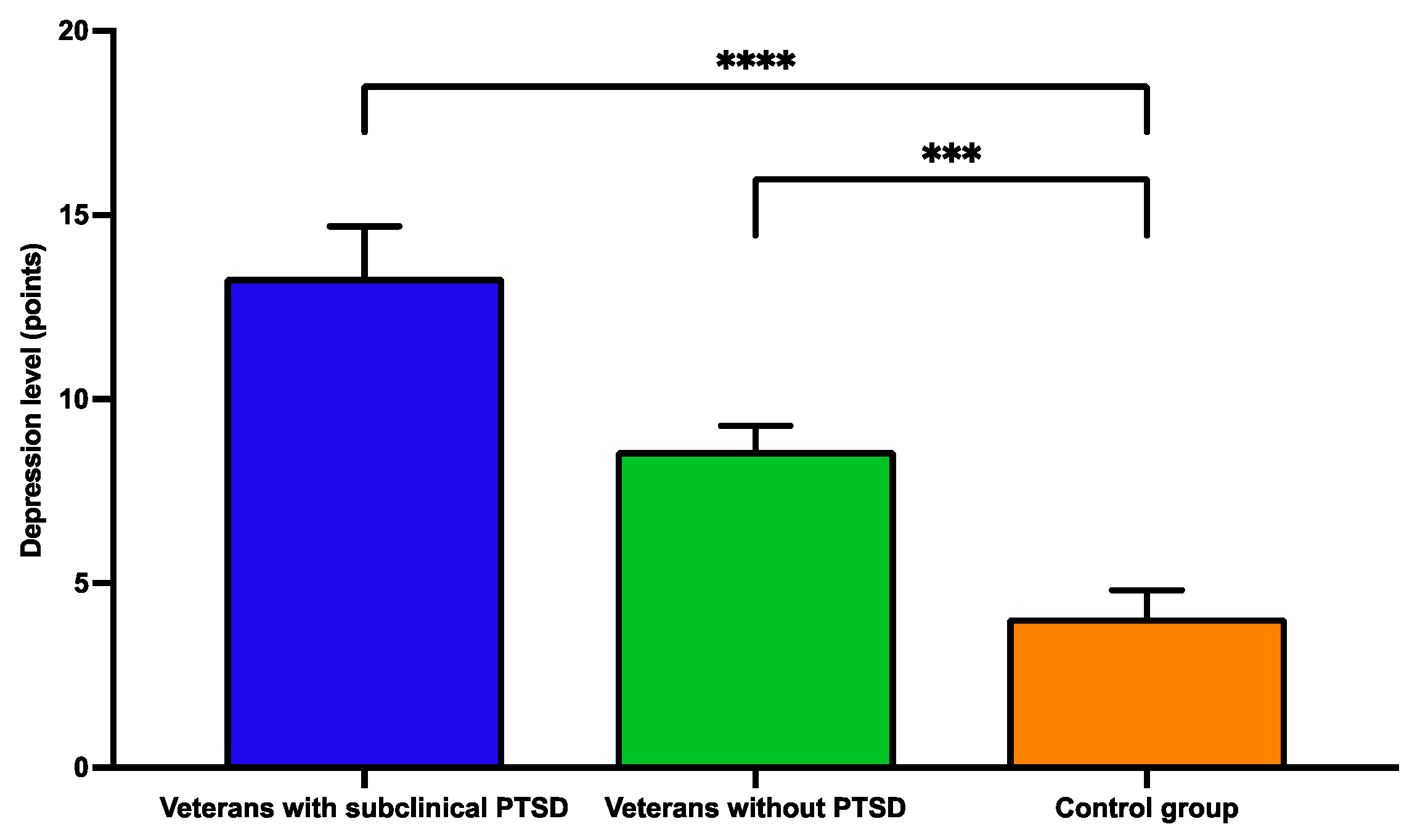

3.2. Results of Psychodiagnostic Methods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| CVD | Cardiovascular diseases |

| AH | Arterial hypertension |

| CHD | Coronary heart disease |

| IHD | Ischemic heart diseases |

| CVD | Cerebrovascular diseases |

| SCL-90-R | The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases |

| ICD-11 | International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision |

References

- Charlson, F.; van Ommeren, M.; Flaxman, A.; Cornett, J.; Whiteford, H.; Saxena, S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellman, S.; Pless Kaiser, A.; Smith, B.; Spiro, A.; Stellman, J. Impact of Persistent Combat-Related PTSD on Heart Disease and Chronic Disease Comorbidity in Aging Vietnam Veterans. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2025, 67, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Labor and Social Protection of the Population of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/enbek/activities/directions?lang=ru (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Singhal, S. Early Life Shocks and Mental Health: The Long-Term Effect of War in Vietnam. J. Dev. Econ. 2019, 141, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovnick, M.O.; Young, Y.; Tran, N.; Teerawichitchainan, B.; Tran, T.K.; Korinek, K. The Impact of Early Life War Exposure on Mental Health among Older Adults in Northern and Central Vietnam. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2021, 62, 526–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neznanov, N.G.; Rukavishnikov, G.V.; Kasyanov, E.D.; Filippov, D.S.; Kibitov, A.O.; Mazo, G.E. Biopsychosocial model in psychiatry as an optimal paradigm for modern biomedical research. Rev. Psychiatr. Med. Psychol. 2020, 2, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Girotti, M.; Bulin, S.; Carreno, F. Effects of chronic stress on cognitive function—From neurobiology to intervention. Neurobiol. Stress. 2024, 33, 100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuliakova, M.; Ratsyborynska-Polyakova, H. The Impact of Chronic Stress On the Human Body and the Role of Psychoeducation in Reducing its Mental Manifestations. Available online: https://e-medjournal.com/index.php/psp/article/view/490 (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Tatayeva, R.; Tussupova, A.; Koygeldinova, S.; Serkali, S.; Suleimenova, A.; Askar, B. The Level of Serotonin and the Parameters of Lipid Metabolism Are Dependent on the Mental Status of Patients with Suicide Attempts. Psychiatry Int. 2024, 5, 773–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013; Available online: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. ICD-11 Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Stellman, S.D.; Pless, K.A.; Smith, B.N.; Spiro, A.; Stellman, J.M. Persistence and Patterns of Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Medical, and Social Dysfunction in Male Military Veterans 50 Years After Deployment to Vietnam. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2025, 67, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qassem, T.; Aly-ElGabry, D.; Alzarouni, A.; Abdel-Aziz, K.; Arnone, D. Psychiatric Co-Morbidities in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Detailed Findings from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey in the English Population. Psychiatr. Q. 2021, 92, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, C.; Shawler, E.; Jordan, C.H.; Moore, M.J.; Jackson, C.A. Veteran and Military Mental Health Issues. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570608/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Veltischev, D.Y. The relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular diseases. Soc. Clin. Psychiatry 2023, 4, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potemina, T.E.; Zuikova, A.A.; Kuznetsova, S.V.; Pereshein, A.V.; Gornushenkov, M.V. Features of adaptation of the cardiovascular system of the veterans’ body after exposure to combat stress and injuries. Bull. Reaviz Med. Inst. 2019, 6, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Krantz, D.S.; Shank, L.M.; Goodie, J.L. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a systemic disorder: Pathways to cardiovascular disease. Health Psychol. 2022, 41, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krittanawong, C.; Maitra, N.S.; Qadeer, U.S.; Wang, Z.; Fogg, S.; Storc, E.A.; Celano, C.M.; Huffman, J.C.; Jha, M.; Charney, D.S.; et al. Association of Depression and Cardiovascular Disease. Am. J. Med. 2023, 136, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naumova, L.A.; Osipova, O.N. Comorbidity: Mechanisms of pathogenesis, clinical significance. Mod. Probl. Sci. Educ. 2020, 5, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Oganov, R.G.; Denisov, I.N.; Simanenko, V.T.; Bakulin, I.G.; Bakulina, N.V.; Boldueva, S.A.; Barbarash, O.N.; Garganeeva, N.P.; Doshchitsin, V.L.; Drapkina, O.V.; et al. Comorbid pathology in clinical practice. Clinical guidelines. Cardiovasc. Ther. Prev. 2017, 16, 5–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Scherer, D. Multimorbidity challenge of evidence-based medicine. Evid. Based Med. 2010, 15, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendlowicz, V.; Garcia-Rosa, M.L.; Gekker, M.; Wermelinger, L.; Berger, W.; de Luz, M.P.; Pires-Dias, P.R.T.; Marques-Portela, C.; Figueira, I.; Mendlowicz, M.V. Post-traumatic stress disorder as a predictor for incident hypertension: A 3-year retrospective cohort study. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, D.J.; Kaizer, A.M.; Kinney, A.R.; Bahraini, N.H.; Forster, J.E.; Brenner, L.A. The unique association of posttraumatic stress disorder with hypertension among veterans: A replication of Kibler et al. (2009) using Bayesian estimation and data from the United States-Veteran Microbiome Project. Psychol. Trauma 2023, 15, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baojian, X.; Yang, Y.; Shun-Guang, W.; Terry, G.B.; Fang, G.; Robert, B.F.; Alan, K.J. Stress-Induced Sensitization of Angiotensin II Hypertension Is Reversed by Blockade of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme or Tumor Necrosis Factor-α. Am. J. Hypertens. 2019, 32, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertkin, A.L. Comorbid Patient: A Guide for Practitioners; Eksmo: Moscow, Russia, 2015; 160p. [Google Scholar]

- Polevaya, N.V.; Shapovalova, M.A. Social status and problems of combat veterans. Bull. AmSU 2019, 84, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fattakhov, V.V.; Demchenkova, G.Z.; Yakubov, M.S.; Maksumova, N.V. Quality of life of veterans of the war in Afghanistan 20 years later. Quality of medical and social support for the population. Qual. Med. Soc. Secur. 2009, 2, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, D.; Smith, B.N.; Fox, A.B.; Amoroso, T.; Taverna, E.; Schnurr, P.P. Consequences of PTSD for the work and family quality of life of female and male U.S. Afghanistan and Iraq War veterans. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palace, M.; Zamazii, O.; Terbeck, S.; Bokszczanin, A.; Berezovski, T.; Gurbisz, D.; Szwejka, L. Mapping the factors behind ongoing war stress in Ukraine-based young civilian adults. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2024, 16, 868–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ST RK 1616-2006 “Good Clinical Practice”. Main Provisions. Available online: http://multiurok.ru/files/gcp-st-rk-1616-2006-nadliezhashchaia-klinichieskai.html (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Disease (ICD)—11th Revision; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://icd.who.int/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Keane, T.M.; Caddell, J.M.; Taylor, K.L. Mississippi scale for combat-related PTSD: Three studies in reliability and validity. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarabrina, N.V.; Agarkov, V.A.; Bykhovets, Y.V.; Kalmykova, E.S.; Makarchuk, A.V.; Padun, M.A.; Udachina, E.G.; Khimchyan, Z.G.; Shatalova, N.E.; Shchepina, A.I. Practical Guide to the Psychology of Post-Traumatic Stress. Part 1. Theory and Methods; Cogito-Center: Moscow, Russia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Lipman, R.S.; Covi, L. SCL-90: An outpatient psychiatric rating scale—Preliminary report. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1973, 9, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tarabrina, N.V. Practicum on Post-Traumatic Stress Psychology; Piter: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2001; 272p. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Jacobs, G.A.; Russell, S.F.; Crane, R.J. Assessment of anger: The State-Trait Anger Scale. In Advances in Personality Assessment; Butcher, J.N., Spielberger, C.D., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1983; Volume 2, pp. 159–187. [Google Scholar]

- Khanin, Y.L. Brief Guide to the Use of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory by Spielberger, C.D.; LNIITEK: Leningrad, Russia, 1976; 40p. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korte, K.J.; Allan, N.P.; Gros, D.F.; Acierno, R. Differential treatment response trajectories in individuals with subclinical and clinical PTSD. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016, 38, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Duan, Y.; Li, J.; Lai, L.; Zhong, Z.; Hu, M.; Ding, S. Somatic symptoms and their association with anxiety and depression in Chinese patients with cardiac neurosis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 4920–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Toussaint, A.; Rosmalen, J.G.M.; Huang, W.L.; Burton, C.; Weigel, A.; Levenson, J.L.; Henningsen, P. Persistent physical symptoms: Definition, genesis, and management. Lancet 2024, 403, 2649–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaei, S.; Kabir, K.; Kazemnejad, A.; Feizi, A.; Mansourian, M.; Keshteli, A.H.; Afshar, H.; Arzaghi, S.M.; Dehkordi, S.R.; Adibi, P.; et al. Explanation of somatic symptoms by mental health and personality traits: Application of Bayesian regularized quantile regression in a large population study. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smakowski, A.; Hüsing, P.; Völcker, S.; Löwe, B.; Rosmalen, J.; Shedden-Mora, M.; Toussaint, A. Psychological risk factors of somatic symptom disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. J. Psychosom. Res. 2024, 181, 11608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, R.S.; Hooten, W.M. Somatic Symptom Disorder. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532253/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Fischer, I.C.; Na, P.J.; Harpaz-Rotem, I.; Marx, B.P.; Pietrzak, R.H. Prevalence, Correlates, and Burden of Subthreshold PTSD in US Veterans. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2024, 85, 57386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichter, B.; Norman, S.; Haller, M.; Pietrzak, R.H. Physical health burden of PTSD, depression, and their comorbidity in the U.S. veteran population: Morbidity, functioning, and disability. J. Psychosom. Res. 2019, 124, 109744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmondson, D.; von Känel, R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease. Lancet 2017, 4, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ullah, H.; Gu, J.; Li, K. Immune-metabolic mechanisms of post-traumatic stress disorder and atherosclerosis. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1123692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.B.; Jaffee, M.S.; Jorge, R.E. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Anxiety-Related Conditions. J. Contin. 2021, 27, 1738–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatayeva, R.; Nurkatov, Y.; Akbayeva, L.; Ilderbayev, O.; Makhanova, A.; Suleimenova, A. Biological Basis for the Formation of Suicidal Behavior: A Review. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran. 2025, 27, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinciotti, C.M.; Fontenelle, L.F.; Van, K.N.; Riemann, B.C. Co-Occurring Obsessive-Compulsive and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Review of Conceptualization, Assessment, and Cognitive Behavioral Treatment. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2022, 36, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, E.; Kline, A.C.; Feeny, N.C.; Zoellner, L.A. Examining PTSD treatment choice among individuals with subthreshold PTSD. Behav. Res. Ther. 2015, 73, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.B.; Schnurr, P.P.; Bovin, M.J.; Friedman, M.J.; Keane, T.M.; Marx, B.P. An empirical investigation of definitions of subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Trauma. Stress. 2024, 37, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyni, S.; Musavi, S.E. Social Isolation of War Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Based on Emotional Inhibition: The Mediating Role of Rejection Sensitivity. J. Mil. Veterans Health 2024, 1, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Saguin, E.; Gomez-Merino, D.; Sauvet, F.; Leger, D.; Chennaoui, M. Sleep and PTSD in the Military Forces: A Reciprocal Relationship and a Psychiatric Approach. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.D.; Olfson, M.; Hellman, F.; Blanco, C.; Guardino, M.; Struening, E.L. Comorbidity, impairment, and suicidality in subthreshold PTSD. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1467–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yehuda, R.; LeDoux, J. Response variation following trauma: A translational neuroscience approach to understanding PTSD. Neuron 2007, 56, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkulova, S.; Tatayeva, R.; Urazalina, D.; Ossadchaya, E.; Rakhmetova, V. Comorbid Conditions in Persons Exposed to Ionizing Radiation and Veterans of the Soviet-Afghan War: A Cohort Study in Kazakhstan. J. Prev. Med. Public. Health 2024, 57, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moye, J.; Kaiser, A.P.; Cook, J.; Pietrzak, R.H. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Older U.S. Military Veterans: Prevalence, Characteristics, and Psychiatric and Functional Burden. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2022, 30, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wal, S.J.; Vermetten, E.; Elbert, G. Long-term development of post-traumatic stress symptoms and associated risk factors in military service members deployed to Afghanistan: Results from the PRISMO 10-year follow-up. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 64, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horesh, D.; Solomon, Z.; Keinan, G.; Ein-Dor, T. The clinical picture of late-onset PTSD: A 20-year longitudinal study of Israeli war veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 208, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unified Register of Legal Acts and Other Documents of the Commonwealth of Independent States. Action Plan “Main Directions” and Other. 2014, pp. 1–32. Available online: https://www.cis.minsk.by/reestrv2/doc/5040#text (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Shabat, N.; Bechor, U.; Yavnai, N.; Tatsa-Laur, L.; Shelef, L. The Link Between Somatization and Dissociation and PTSD Severity in Veterans Who Sought Help From the IDF Combat Stress Reaction Unit. Mil. Med. 2024, 189, e2562–e2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodson, J.; Ponder, W.N.; Carbajal, J.; Cassiello-Robbins, C. Combat veteran mental health outcomes after short-term counseling services. J. Veterans Stud. 2025, 11, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, K.A.; Sripada, R.K.; Defever, M.; Rauch, S.M. Comorbid mood and anxiety disorders and severity of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in treatment-seeking veterans. Psychol. Trauma 2019, 11, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Following Taliban Takeover, 9 in 10 Afghanistan Vets have Exacerbated Mental Health Symptoms. Online Therapy. Available online: https://www.onlinetherapy.com/taliban-takeover-exacerbates-vets-mental-health-symptoms/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Marmar, C.R.; Schlenger, W.; Henn-Haase, C.; Qian, M.; Purchia, E.; Li, M.; Corry, N.; Williams, C.S.; Ho, C.-L.; Horesh, D.; et al. Course of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder 40 Years After the Vietnam War: Findings From the National Vietnam Veterans Longitudinal Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghammer, L.; Marx, M.F.; Odom, E.; Chisolm, N. Wounded Warrior Project. Annual Warrior Survey. Longitudinal: Wave 1, Tech. Rep. 2022. Available online: https://www.woundedwarriorproject.org/media/4ptekte3/2021-report-of-findings.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Deferio, J.J.; Breitinger, S.; Khullar, D.; Sheth, A.; Pathak, J. Social determinants of health in mental health care and research: A case for greater inclusion. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2019, 26, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, N.; Holliday, R.; Ranney, R.M.; Bernhard, P.A.; Vogt, D.; Hoffmire, C.A.; Blosnich, J.R.; Schneiderman, A.I.; Maguen, S. Relationship of social determinants of health with symptom severity among Veterans and non-Veterans with probable posttraumatic stress disorder or depression. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2023, 58, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdar, N.; Khan, S.; Brostow, D.P.; Spencer, L.; Roy, S.; Sisson, A.; Hundt, N.E. Association between modifiable social determinants and mental health among post-9/11 Veterans: A systematic review. J. Mil. Veteran Fam. Health 2023, 9, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursa, E.K.; Barth, S.K.; Schneiderman, A.I.; Bossarte, R.M. Physical and mental health status of Gulf War and Gulf Era veterans: Results from a large population-based epidemiological study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, L.E.; Sexton, M.B.; Raggio, G.A.; Porter, K.E.; Rauch, S.A. Posttraumatic stress disorder and somatic complaints: Contrasting Vietnam and OIF/OEF Veterans’ experiences. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 82, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttner, M.M.; Godfrey, K.M.; Floto, E.; Pittman, J.; Lindamer, L.; Afari, N. Combat exposure and pain in male and female Afghanistan and Iraq veterans: The role of mediators and moderators. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 257, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargrave, A.S.; Sumner, J.A.; Ebrahimi, R.; Cohen, B.E. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as a Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Disease: Implications for Future Research and Clinical Care. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2022, 24, 2067–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, C.J.; Schwartz, L.L.; Cohen, B.E.; Fayad, Z.A.; Gillespie, C.F.; Liberzon, I.; Pathak, G.A.; Polimanti, R.; Risbrough, V.; Ursano, R.J.; et al. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Cardiovascular Disease: State of the Science, Knowledge Gaps, and Research Opportunities. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 1207–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, J.T.; Dell, N.A.; Issa, M.; Watkins, M.A. Associations between Allostatic Load and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Scoping Review. Health Soc. Work. 2022, 47, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen van Vuren, E.; van den Heuvel, L.L.; Hemmings, S.M.; Seedat, S. Cardiovascular risk and allostatic load in PTSD: The role of cumulative trauma and resilience in affected and trauma-exposed adults. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2025, 182, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zuiden, M.; Geuze, E.; Willemen, H.L.; Vermetten, E.; Maas, M.; Heijnen, C.J.; Kavelaars, A. Long-term impact of military deployment on physical fitness, health, and allostatic load in Dutch veterans. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, J.A.; Kariya, M.; Charns, M.P.; Koenen, K.C.; Kubzansky, L.D. Posttraumatic stress disorder and allostatic load: A systematic review. Psychosom. Med. 2023, 85, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakić, D.; Stipčević, M.; Morić Perić, M.; Bakotić, Z.; Lončar, J.V.; Bačkov, K.; Vojković, M.; Jakab, J.; Včev, A. Chronic Medical Conditions In Croatian War Veterans Compared To The General Population: 25 Years After The War. Acta Clin. Croat. 2023, 62, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n = 293, 100% | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Nationality | ||

| Kazakhs | 234 | 79.7 |

| Russians | 25 | 8.5 |

| Ukrainians | 18 | 6.2 |

| Other nationalities | 16 | 5.6 |

| Age range | ||

| 50–54 | 91 | 30.9% |

| 55–59 | 99 | 33.7% |

| 60–64 | 82 | 28.1% |

| 65–69 | 16 | 5.6% |

| 70 and older | 5 | 1.7% |

| Education | ||

| Secondary | 109 | 37.2% |

| Secondary Special | 90 | 41.7% |

| Higher | 29 | 21.1% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 174 | 59.5% |

| Divorced | 90 | 30.8% |

| Single | 29 | 9.7% |

| Employment Status | ||

| Employed: | 159 | 54.3% |

| (a) engaged in physical labor | 89 | 30.4% |

| (b) engaged in security activities | 62 | 21.1% |

| (c) other areas of employment | 8 | 2.8% |

| Non-employed: | 134 | 45.7% |

| (a) pensioners | 59 | 20.1% |

| (b) war invalids | 12 | 4.1% |

| (c) invalids due to other groups of diseases | 63 | 21.5% |

| Indicator | Veterans with Subclinical PTSD, n = 74 | Veterans Without PTSD, n = 219 | Control Group, n = 149 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mississippi PTSD Scale | 92.85 ± 14.69 | 68.06 ± 5.15 | 63.40 ± 7.93 | p1 < 0.001 |

| p2 < 0.001 | ||||

| p3 = 0.005 |

| Scale | Veterans with Subclinical PTSD/Veterans Without PTSD | Veterans with Subclinical PTSD/ Control Group | Veterans Without PTSD/ Control Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U1 | Me1 | p1 | U2 | Me2 | p2 | U3 | Me3 | p3 | |

| Somatization (SOM) | 1025 | 0.04 | 0.354 | 116 | 0.37 | 0.016 * | 404 | 0.33 | 0.030 * |

| Obsessive–Compulsive Disorders (O-S) | 804 | 0.25 | 0.014 * | 60.5 | 0.65 | <0.001 | 293.5 | 0.4 | 0.001 *** |

| Interpersonal Sensitivity (INT) | 967 | 0.34 | 0.185 | 88.5 | 0.56 | 0.001 ** | 344.5 | 0.22 | 0.005 ** |

| Depression (DEP) | 998.5 | 0.04 | 0.268 | 79 | 0.43 | 0.001 *** | 288 | 0.39 | 0.001 *** |

| Anxiety (ANX) | 1049 | 0.2 | 0.442 | 121.5 | 0.5 | 0.023 * | 382 | 0.3 | 0.016 * |

| Hostiles (HOS) | 1020 | 0.17 | 0.333 | 64.5 | 0.45 | <0.001 | 261 | 0.28 | 0.0002 *** |

| Phobic Anxiety (PHOB) | 784.5 | 0.21 | 0.009 ** | 52.5 | 0.64 | <0.001 | 245 | 0.43 | <0.001 |

| Paranoid Symptoms (PAR) | 108 | 0.30 | 0.008 ** | 108 | 0.3 | 0.007 ** | 424.5 | 0.13 | 0.048 * |

| Psychoticism (PSY) | 1010 | 0.25 | 0.276 | 17.5 | 0.21 | 0.351 | 610 | 0.04 | 0.898 |

| Global Symptom Severity Index (GSI) | 771.5 | 0.25 | 0.008 ** | 11 | 0.58 | <0.001 | 138.5 | 0.33 | <0.001 |

| MS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indicators | r | p-Value |

| Somatization (SOM) | 0.624 * | 0.015 |

| Obsessive–Compulsive Disorders (O-S) | 0.253 | 0.359 |

| Interpersonal Sensitivity (INT) | 0.686 ** | 0.006 |

| Depression (DEP) | 0.723 ** | 0.003 |

| Anxiety (ANX) | 0.569 * | 0.029 |

| Hostiles (HOS) | 0.462 | 0.084 |

| Phobic Anxiety (PHOB) | 0.551 * | 0.036 |

| Paranoid Symptoms (PAR) | 0.019 | 0.945 |

| Psychoticism (PSY) | 0.302 | 0.269 |

| Global Symptom Severity Index (GSI) | 0.581 * | 0.025 |

| Type of Anxiety | Veterans with Subclinical PTSD, n = 74 | Veterans Without PTSD, n = 219 | Control Group, n = 149 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Situational anxiety (points) | 44.96 ± 6.39 | 41.43 ± 6.03 | 29.87 ± 6.5 | p1 = 0.379 p2 < 0.001 p3 < 0.001 |

| Personal anxiety (points) | 44.14 ± 5.49 | 42.55 ± 6.24 | 36.13 ± 6.82 | p1 = 0.753 p2 = 0.003 p3 = 0.002 |

| Diseases | Veterans with Subclinical PTSD, n = 74 | Veterans Without PTSD, n = 219 | Control Group, n = 149 | χ2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Discirculatory encephalopathy (DEP) stage 2 | 29 (39.2%) | 106 (48.4%) | 15 (10.3%) | χ21 = 1.89 χ22 = 26.48 *** χ23 = 59.04 *** | p1 = 0.169 p2 < 0.001 p3 < 0.001 |

| Discirculatory encephalopathy (DEP) stage 3 | 3 (3.9%) | 20 (11.4%) | 3 (2%) | χ21 = 1.97 χ22 = 0.79 χ23 = 7.67 ** | p1 = 0.160 p2 = 0.375 p3 = 0.005 |

| Arterial hypertension (AH) stage 1 | 12 (16.5%) | 25 (7.2%) | 5 (3.4%) | χ21 = 1.15 χ22 = 11.61 *** χ23 = 7.69 ** | p1 = 0.282 p2 = 0.001 p3 = 0.005 |

| Arterial hypertension (AH) stage 2 | 22 (30.1%) | 40 (18.3%) | 15 (10.1%) | χ21 = 4.35 * χ22 = 13.81 *** χ23 = 4.69 * | p1 = 0.36 p2 < 0.001 p3 = 0.030 |

| Arterial hypertension (AH) stage 3 | 33 (45.2%) | 65 (29.8%) | 32 (21.3%) | χ21 = 5.53 * χ22 = 12.8 *** χ23 = 3.07 | p1 = 0.019 p2 < 0.001 p3 = 0.079 |

| Ischemic heart disease (IHD) | 34 (45.5%) | 68 (31.1%) | 20 (13.4%) | χ21 = 5.41 * χ22 = 28.5 *** χ23 = 15.14 *** | p1 = 0.020 p2 < 0.001 p3 < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) type 2 | 15 (20.3%) | 23 (10.4%) | 9 (6.1%) | χ21 = 4.68 * χ22 = 10.42 ** χ23 = 2.22 | p1 = 0.031 p2 = 0.001 p3 = 0.136 |

| Sensory disorders | 14 (18.9%) | 44 (20.1%) | 29 (19.7%) | χ21 = 0.04 χ22 = 0.01 χ23 = 0.02 | p1 = 0.827 p2 = 0.923 p3 = 0.882 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 6 (7.8%) | 21 (9.4%) | 7 (4.7%) | χ21 = 0.15 χ22 = 1.05 χ23 = 3.02 | p1 = 0.703 p2 = 0.306 p3 = 0.082 |

| Spinal diseases | 15 (20.7%) | 76 (34.6%) | 21 (14.1%) | χ21 = 5.38 * χ22 = 1.39 χ23 = 19.4 *** | p1 = 0.020 p2 = 0.237 p3 < 0.001 |

| Other concomitant diseases | 8 (10.5%) | 30 (13.7%) | 18 (12.1%) | χ21 = 0.41 χ22 = 0.08 χ23 = 0.20 | p1 = 0.523 p2 = 0.781 p3 = 0.651 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ossadchaya, E.; Tatayeva, R.; Sembayeva, Z.; Nursafina, A.; Zhakenova, M.; Slamkhanova, G. Long-Term Consequences of Combat Stress in Afghan War Veterans: Comorbidity of PTSD and Physical and Mental Health Conditions. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040141

Ossadchaya E, Tatayeva R, Sembayeva Z, Nursafina A, Zhakenova M, Slamkhanova G. Long-Term Consequences of Combat Stress in Afghan War Veterans: Comorbidity of PTSD and Physical and Mental Health Conditions. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(4):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040141

Chicago/Turabian StyleOssadchaya, Ekaterina, Roza Tatayeva, Zhibek Sembayeva, Akmaral Nursafina, Mira Zhakenova, and Gaukhar Slamkhanova. 2025. "Long-Term Consequences of Combat Stress in Afghan War Veterans: Comorbidity of PTSD and Physical and Mental Health Conditions" Psychiatry International 6, no. 4: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040141

APA StyleOssadchaya, E., Tatayeva, R., Sembayeva, Z., Nursafina, A., Zhakenova, M., & Slamkhanova, G. (2025). Long-Term Consequences of Combat Stress in Afghan War Veterans: Comorbidity of PTSD and Physical and Mental Health Conditions. Psychiatry International, 6(4), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040141