Abstract

Mental health issues and insufficient physical activity (PA) among students pose significant public health concerns. This study aimed to examine the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, alongside PA levels, among Croatian medical students, with a focus on sex-specific differences and associations between these variables. A cross-sectional study was carried out during May and June 2025 among medical students at the University of Osijek, Croatia. Participants completed a self-reported questionnaire consisting of three sections: sociodemographic characteristics, the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21), and the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF). The study included 244 students (70 males, 174 females) with a median age of 21 years (IQR: 20–23). Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress were reported by 33.1%, 48.4%, and 42.6% of participants, respectively. According to IPAQ-SF, 39.7% of students reported PA levels below current recommendations. Female students reported significantly higher depression (p = 0.009), anxiety (p < 0.001), and stress scores (p < 0.001), lower levels of moderate (p = 0.009) and vigorous PA (p < 0.001), and more time spent sitting (p = 0.006) compared to their male counterparts. Furthermore, significant positive correlations were identified between sitting time and depression (ρ = 0.17, p = 0.01), anxiety (ρ = 0.18, p = 0.006), and stress (ρ = 0.26, p < 0.001). Conversely, higher PA—particularly vigorous activity—was associated with lower levels of depression (ρ = −0.21, p = 0.001) and anxiety (ρ = −0.15, p = 0.018). Croatian medical students demonstrated a substantial prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, combined with inadequate levels of PA. These findings highlight the importance of implementing strategies aimed at supporting mental health and fostering regular PA among future healthcare professionals.

Keywords:

anxiety; depression; mental health; physical activity; psychological stress; students; medical 1. Introduction

Mental health disorders among university students represent an increasing public health concern [1]. Studies indicate that university students exhibit higher levels of depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms compared to their non-student peers [1,2]. Numerous studies worldwide have assessed depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms using the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) [3]. These studies consistently report substantial psychological distress among students, although prevalence rates vary considerably across populations. Reported prevalences were 40.6%, 29.9%, and 27.5% in Portugal; 26.4%, 25.7%, and 12.5% in China; 66%, 71.3%, and 69% in Malaysia; and 43.4%, 55.6%, and 45.8% in Saudi Arabia, for depression, anxiety, and stress, respectively [4,5,6,7]. With regard to medical students, a meta-analysis by Rotenstein et al. (2016) encompassing more than 120,000 participants estimated a global prevalence of depressive symptoms at 27% [8], while a subsequent meta-analysis by Quek et al. (2019) reported a 34% prevalence of anxiety symptoms among over 40,000 medical students [9]. Comparisons between medical and non-medical students remain inconclusive, with some studies suggesting higher levels of depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms in medical students [10,11], while others report no significant differences [12,13]. The reasons for these inconsistencies remain unclear.

In Croatia, elevated levels of psychological distress—particularly symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress—have also been documented. During the COVID-19 pandemic, university students in Croatia exhibited high prevalence rates of these symptoms, comparable to those reported globally [14]. A similar trend was observed in a multicenter cross-sectional study conducted among medical students in Osijek and Split, Croatia, one year after the official end of the pandemic, with 38.8% reporting symptoms of depression, 45.3% symptoms of anxiety, and 40.4% symptoms of stress [15].

University students are generally characterized by low levels of physical activity (PA) and high levels of sedentary behaviour [16,17]. Several recent studies worldwide employing the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) have demonstrated that a considerable proportion of students engage in PA below the recommended levels or are classified as inactive [16,18,19]. For instance, Edelmann et al. (2022) reported that 22.4% of a sample of 4351 German students were insufficiently active [16], while Roberts et al. (2024) found that among 590 UK university students, 37% did not meet the 150 min moderate-to-vigorous intensity weekly PA guideline and 56% did not meet strength-based activity recommendations [18]. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2024) found that 45.1% of 1216 healthcare students in China engaged in insufficient PA, defined as less than 600 MET-minutes per week [19]. In terms of sedentary behaviour, Barbosa et al. (2024) reported that among 8650 Brazilian university students, 55.1% spent more than nine hours per day sitting [20]. A similar trend has been observed in Croatia, where a cross-sectional study using the IPAQ involving 2100 university students found that 23% of participants did not meet the physical activity recommendations defined by the WHO Global Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour [21,22].

Moreover, numerous studies suggest that higher levels of PA are associated with lower levels of depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms [23,24,25]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by Huang et al. (2024) demonstrated that PA interventions among undergraduate students significantly reduced symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress [23]. Similarly, Guerriero et al. (2025), analyzing 61 studies, reported a positive correlation between PA and stress reduction [26]. However, contrasting findings have been reported in Croatia. For example, a study by Talapko et al. (2021), conducted among healthcare students at the University of Osijek during the COVID-19 pandemic, found no statistically significant association between PA and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress [27]. Research on this topic in the post-pandemic period remains limited, particularly among medical students. To date, only one cross-sectional study has examined the prevalence of these symptoms in this population, focusing exclusively on their association with sleep quality [15]. That study found that poorer sleep quality, as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), was associated with higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. However, the potential relationship between these symptoms and PA, as well as possible sex-specific differences in these variables among medical students in Croatia, has not yet been investigated. Given the vulnerability of this population and the potential protective role of PA, further research is warranted.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were fourfold: (1) to evaluate the prevalence and severity of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms using the DASS-21; (2) to assess the extent of engagement in different types of PA, including walking, moderate PA, and vigorous PA, as well as the amount of sitting time, measured by the IPAQ-short form (IPAQ-SF); (3) to investigate sex-specific differences in depression, anxiety, and stress levels, as well as in levels of engagement in walking, moderate PA, vigorous PA, and sedentary behaviour; and (4) to examine potential associations between levels of depression, anxiety, and stress and different types of PA and sitting time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

This cross-sectional study was carried out among medical students at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Osijek, Croatia. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Osijek (Approval code: 2158-61-46-25-123; Approval date: 6 May 2025). Recruitment was conducted through the institutional email system, inviting students to complete an online questionnaire hosted on Google Forms. The invitation contained a comprehensive Participant Information Sheet describing the study objectives, design, procedures, and expectations of participants. Participation was voluntary, with full anonymity ensured, and respondents retained the right to withdraw at any stage without providing a reason. Access to the questionnaire was provided via a secure hyperlink included in the invitation. Prior to beginning the survey, each participant confirmed electronic informed consent. Copies of the Participant Information Sheet and the Consent Form are available in Supplement Files S1 and S2. The initial invitation was distributed on 15 May 2025, and the survey remained open until 5 June 2025, when data collection concluded. Overall, the recruitment procedure was similar to that employed in our previous cross-sectional study [15].

The minimum sample size was determined with reference to the total population of medical students at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Osijek (N = 459). Based on a 95% confidence level (Z = 1.96), a 5% margin of error, and a conservative prevalence estimate of 50%, the required sample size was 210. The computation applied the finite population correction formula:

where n is the required sample size, N the population size, Z the Z-score (1.96 for 95%), p the estimated population proportion (0.5), and e the margin of error (0.05).

Out of 459 students invited to participate in the study, 255 agreed to take part, yielding a response rate of 55.6%. Of these, 11 participants did not complete the questionnaire in full and were excluded from the analysis. This resulted in a final sample of 244 fully completed responses, which exceeded the minimum required sample size determined by the power analysis and ensured adequate statistical power.

2.2. Instruments

Participants completed an anonymous, self-administered online questionnaire in the Croatian language. The English version of the questionnaire is provided in Supplementary File S2. The questionnaire consisted of three sections (57 items in total), and the estimated time to complete it was approximately 7 to 10 min. The first section gathered data on participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. The second section assessed symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21). The third section evaluated physical activity levels using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF).

Sociodemographic characteristics were assessed using a self-administered questionnaire adapted for this study, similar to the one used by Vidović et al. (2025) [15]. The questionnaire included items on sex, age, year of study, BMI (based on self-reported height and weight), GPA, hours of studying per day, place of residence, living arrangements, financial status, and relationship status. It also covered smoking, alcohol, and psychoactive substance use.

The DASS-21 is a shortened version of the original Depression Anxiety Stress Scale—42 Items (DASS-42), developed to identify and differentiate symptoms of three related emotional states: depression, anxiety, and stress. In this study, the validated Croatian version of the DASS-21 was used [28]. This self-report instrument is designed to assess the severity of symptoms across three subscales: Depression (DASS-21 D), Anxiety (DASS-21 A), and Stress (DASS-21 S), each consisting of seven items. Participants rated how much they had experienced each symptom over the past week using a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (“Did not apply to me at all”) to 3 (“Applied to me very much or most of the time”). Based on the total scores for each subscale—calculated by summing the scores and multiplying by two—participants were categorized into five levels of symptom severity: for depression, normal (0–9), mild (10–13), moderate (14–20), severe (21–27), and extremely severe (28+); for anxiety, normal (0–7), mild (8–9), moderate (10–14), severe (15–19), and extremely severe (20+); and for stress, normal (0–14), mild (15–18), moderate (19–25), severe (26–33), and extremely severe (34+) [29]. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the DASS-21 subscales were: Depression α = 0.86, Anxiety α = 0.84, and Stress α = 0.90. The total DASS-21 score had an alpha of 0.94.

The IPAQ-SF is a widely used self-report instrument developed for international use to assess PA in adults aged 15–69 years. It provides an estimate of the frequency and duration of physical activity at different intensities over the previous seven days [30]. The short form of the IPAQ consists of seven items that measure time spent in vigorous-intensity and moderate-intensity activities, walking, and sitting. Respondents are asked to report the number of days per week and the average time per day spent engaging in each type of activity. These data are used to calculate total PA expressed in metabolic equivalent minutes per week (MET-min/week). Vigorous-intensity MET-minutes per week were calculated by multiplying the number of minutes of vigorous activity per day by the number of days per week and by 8.0 METs; moderate-intensity MET-minutes used a factor of 4.0 METs, and walking used 3.3 METs, with total PA (total MET-min/week) obtained as the sum of the vigorous-, moderate-, and walking-specific MET-minutes per week. The validated Croatian version of the IPAQ-SF was used in this study [31]. As the IPAQ-SF is based on frequency and duration estimates rather than latent constructs, internal consistency measures such as Cronbach’s α are not applicable. Instead, reliability has been consistently demonstrated through test–retest methods, with the Croatian validation reporting moderate to high correlations (0.54–0.91) and similar findings internationally [31,32]. Due to the cross-sectional design of the present study, no additional reliability testing (e.g., test–retest or accelerometry) was conducted.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data distribution was examined with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, while equality of variances was checked using Levene’s test. Categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages, whereas continuous variables are summarized with medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Although the sample was relatively large (n = 244), deviations from normality and the results of Levene’s test indicated the use of non-parametric methods.

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare sex-specific differences in median values of depression, anxiety, and stress scores, as well as walking (MET-min/week), moderate physical activity (MET-min/week), vigorous/intense physical activity (MET-min/week), total MET-min/week, and sitting time. In addition, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied to compare depression, anxiety, and stress scores between participants who met the recommended levels of physical activity and those who did not. To assess the magnitude of observed differences, the standardized effect size r was calculated and interpreted according to Cohen’s criteria (small ≈ 0.1, medium ≈ 0.3, large ≥ 0.5).

Associations between DASS 21 scores (depression, anxiety, stress) and IPAQ-SF measures (walking, moderate and vigorous activity, total MET-min/week, and sitting time) were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients.

Multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to examine the associations between physical activity variables and symptoms of depression (D score), anxiety (A score), and stress (S score). For each outcome, a separate regression model was fitted, including the following predictors: walking (MET-min/week), moderate-intensity physical activity (MET-min/week), vigorous-intensity physical activity (MET-min/week), and sitting time (minutes/day). Total MET-min/week was excluded from the models to avoid multicollinearity, as it is derived directly from the other physical activity variables. Prior to analysis, the assumptions of multiple linear regression were evaluated. Multicollinearity was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), with values >5 considered indicative of problematic collinearity. All predictor variables met this criterion after removing Total MET-min/week. The regression coefficients for physical activity variables were rescaled by a factor of 1000 (expressed as MET-min/week × 10−3) to facilitate interpretation. Model outputs included unstandardized beta coefficients (β), standard errors (SE), t-values, and p-values for each predictor, as well as model-level statistics: coefficient of determination (R2), adjusted R2, F-statistic with associated p-value, and standard error of the estimate (SEE). Statistical analysis was performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Among the participants, there were 70 males (28.7%) and 174 females (71.3%), with a median age of 21 years (IQR: 20–23). An overview of additional sociodemographic data is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant sociodemographic characteristics (n = 244).

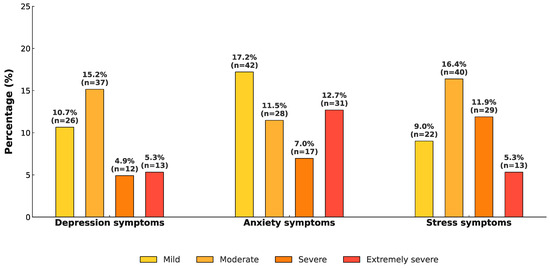

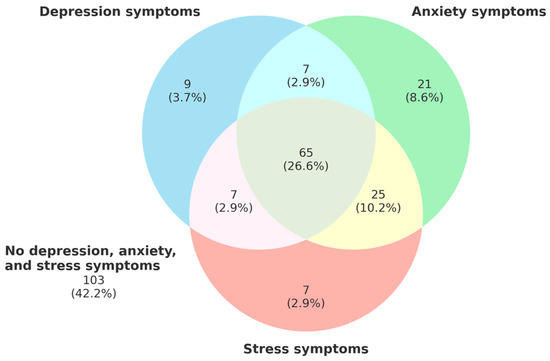

Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress were reported by 36.1%, 48.4%, and 42.6% of participants, respectively. Among female students, 39.7% (n = 69) reported symptoms of depression, 54.6% (n = 95) symptoms of anxiety, and 50.6% (n = 88) symptoms of stress. In contrast, among male students, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress were reported by 27.1% (n = 19), 32.9% (n = 23), and 22.9% (n = 16), respectively. Severe or extremely severe symptom levels were observed in 10.2% of participants for depression, 19.7% for anxiety, and 17.2% for stress. The distribution of symptom severity levels (mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe) across the three domains is presented in Figure 1. Additionally, 26.6% of participants reported concurrent symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, as illustrated in the Venn diagram (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Distribution of severity levels of depression, anxiety, and stress among medical students (n = 141), according to the DASS-21.

Figure 2.

Coexistence of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms among medical students: Venn diagram (n = 141, 57.8%).

Regarding PA, 147 (60.3%) participants met the WHO guidelines, which recommend that individuals aged 18–64 should engage in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity PA per week, or at least 75 min of vigorous-intensity PA, or an equivalent combination of both [22]. Notably, 96 (39.3%) participants self-reported sitting for 8 or more hours per day (Table 2).

Table 2.

The self-reported depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms (according to the DASS-21), and physical activity (according to the IPAQ-SF) (n = 244).

In the sex-specific comparison, female students exhibited significantly higher scores of depression (U = 7381, p = 0.009), anxiety (U = 7909, p < 0.001), and stress (U = 8513, p < 0.001) compared to their male counterparts. Furthermore, female students reported significantly lower IPAQ-SF MET-min/week values for moderate-intensity PA (U = 4787, p = 0.009) and vigorous-intensity PA (U = 4102, p < 0.001). Females also showed significantly lower total MET-min/week values (U = 4303, p < 0.001). Additionally, female participants reported spending significantly more time sitting (U = 7466, p = 0.006) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sex-based differences in depression, anxiety, stress scores and physical activity variables. Mann–Whitney U test (n = 244).

A comparison of depression, anxiety, and stress scores between participants who met the recommended levels of PA according to WHO guidelines and those who did not revealed that those who met the recommended levels of PA had lower depression (U = 5609, p = 0.005) and anxiety scores (U = 5585, p = 0.004) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of depression, anxiety, and stress scores based on the physical activity categories. Mann–Whitney U test (n = 244).

A statistically significant negative correlation was found between intense/vigorous PA and depression (ρ = −0.21, p = 0.001), as well as anxiety scores (ρ = −0.15, p = 0.018). A negative correlation was also observed between total MET-min/week and both depression (ρ = −0.22, p < 0.001) and anxiety scores (ρ = −0.14, p = 0.029). Furthermore, a significant positive correlations were identified between sitting time and depression (ρ = 0.17, p = 0.01), anxiety (ρ = 0.18, p = 0.006), and stress (ρ = 0.26, p < 0.001). The remaining correlations between depression, anxiety, and stress scores and various types of PA are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Correlations of depression, anxiety, and stress scores with physical activity variables in medical students, assessed by Spearman’s rank coefficients (ρ) (n = 244).

Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to examine the associations between physical activity variables and mental health outcomes. Three separate models were created, with depression, anxiety, and stress scores as the dependent variables, respectively (Table 6). The regression model for depression was significant, F(4, 239) = 2.740, p = 0.029, R2 = 0.044, with sitting time positively associated with depression scores (β = 0.003, p = 0.023). The model for anxiety was also significant, F(4, 239) = 2.751, p = 0.029, R2 = 0.044, in which vigorous physical activity was negatively associated with anxiety (β = −0.409, p = 0.041) while sitting time was positively associated (β = 0.004, p = 0.017). The model for stress was also significant, F(4, 239) = 5.261, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.081, with sitting time emerging as a significant positive correlate (β = 0.007, p < 0.001). Multicollinearity was not a concern, as indicated by VIF values ranging from 1.01 to 1.08.

Table 6.

Multiple linear regression analyses with DASS-21 subscale scores (depression, anxiety, and stress) as dependent variables, and IPAQ-SF activity types (walking, moderate, vigorous/intense, and sitting time) as independent variables (n = 244).

4. Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that a considerable proportion of students reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, with higher prevalence observed among those who engaged in lower levels of PA. In the sex-specific analysis, female students reported significantly higher levels of depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms, engaged in lower levels of PA, and spent more time sitting compared to their male counterparts. Furthermore, increased sitting time was positively associated with higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, whereas vigorous and overall physical activity were inversely associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms.

Overall, systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicate that medical students worldwide face a substantial burden of depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms. While some meta-analyses have reported lower rates of depression and anxiety compared with our findings [8,9], others have described prevalence levels comparable to or even higher than those observed in our sample [33,34]. Cross-sectional studies further illustrate these variations. For example, Haruna et al. (2025), using the DASS-21, reported markedly higher prevalence rates of depression (49%), anxiety (75%), and stress (73.3%) than our study, likely due to their focus on first-year medical students—a group particularly vulnerable to major life transitions, academic pressures, and limited coping strategies [3]. By contrast, Wang et al. (2023) found lower prevalence of depression (26.4%), anxiety (25.7%), and stress (12.5%) during the COVID-19 pandemic [5]. Conversely, Wong et al. (2023) observed considerably higher rates of depression (66%), anxiety (71.4%), and stress (68%) during the pandemic [6]. Such discrepancies are likely attributable to differences in study populations, sampling periods, and methodological approaches. Although higher levels of psychological distress during the pandemic compared with pre-pandemic periods have been consistently documented, the extent to which depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms differ between the pandemic and post-pandemic periods among student populations remains insufficiently understood. This underscores the need for additional systematic reviews and meta-analyses—particularly longitudinal investigations—to elucidate the trajectory and potential risk factors of these symptoms during and after the pandemic.

An analysis of participants’ PA revealed that approximately 39.7% of medical students engaged in levels of PA below the thresholds recommended by the WHO Global Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour, which advise that adults aged 18–64 should accumulate at least 150–300 min of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, or 75–150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, or an equivalent combination of both per week [22]. In addition, 39.3% of students reported sedentary behaviour exceeding the recommended limit of eight hours per day for this age group. A large-scale meta-analysis by Strain et al. (2024), which included 507 studies across 163 of 197 countries, found that nearly one-third of adults worldwide were insufficiently physically active (31.3% [95% CI, 28.6–34.0]), a prevalence similar to that observed in our study [35]. In our country, Štefan et al. (2018) conducted a cross-sectional study using the IPAQ among university students and reported a significantly higher proportion of sufficiently active students compared with our findings [21]. This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that our study focused exclusively on medical students, whose education is characterized by a demanding academic workload, extended periods of sedentary study, elevated stress levels, and limited time or opportunities for regular PA—all of which are distinctive features of medical training [36,37]. At the international level, Roberts et al. (2025) reported that 37% of university students in the UK did not meet PA recommendations, which is comparable to the prevalence of insufficient PA observed in our sample [18]. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2024), using the IPAQ-SF among Chinese students, found that 45% of participants fell into the low PA category, a higher proportion of inactivity than in our study [19]. This difference may be attributable to the fact that their study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, when movement restrictions and lockdowns likely limited opportunities for PA [38].

Previous research suggests that PA significantly reduces the risk of major non-communicable diseases, including coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and stroke, while also contributing to increased life expectancy [39,40]. In addition to the well-established link between PA and physical health, the findings of our study indicate a relationship between PA, sedentary behaviour, and mental health outcomes. Specifically, engagement in PA—particularly vigorous-intensity activity—was associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety, whereas increased sitting time was linked to higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress among medical students. These findings are consistent with a meta-analysis of 218 randomized controlled trials by Noetel et al. (2024), which demonstrated that vigorous PA significantly reduces depressive symptoms [41], as well as with the results of a meta-analysis by Huang et al. (2024), which reported that PA significantly decreases both depression and anxiety among undergraduate students [23]. In line with this, a meta-analysis of 12 prospective studies by Huang et al. (2020) confirmed a positive association between sedentary behaviour and the risk of depression in adults [42], while a systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 observational studies by Allen et al. (2019) indicated that sedentary behaviour is also associated with an increased risk of anxiety [43]. Further supporting our findings, several recent cross-sectional studies using the same instruments as in our study (DASS-21 and IPAQ-SF) have likewise reported that higher levels of PA are significantly and negatively correlated with DASS-21 scores, that is, with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress [44,45,46]. Although the associations identified in our study reached statistical significance, their strength was weak, and the cross-sectional design precludes any inference of causality. Nevertheless, this study is, to our knowledge, the first to demonstrate an association between sitting time and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress among Croatian medical students. Future research—particularly longitudinal studies, randomized controlled trials, and meta-analytic or meta-regression approaches—is needed to further elucidate the direction, magnitude, and potential risk factors underlying the relationships between different types of PA, sedentary behaviour, and mental health outcomes in this subpopulation.

The sex-specific analysis revealed that female medical students reported higher levels of depression, anxiety, and particularly stress. A similar pattern was observed in a study conducted in Croatia in the year following the COVID-19 pandemic, which found that female medical students at the Universities of Split and Osijek exhibited more pronounced symptoms than male students [15]. These differences may be influenced by a multifactorial interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors. Potential contributors include hormonal fluctuations, differences in emotional reactivity, coping strategies, and help-seeking behaviour, as well as varying levels of perceived academic pressure and social expectations—all of which may differentially affect mental health outcomes among male and female medical students [36,37]. Furthermore, the sex-specific analysis revealed that female students engaged in lower levels of PA, including both vigorous and moderate types, and spent more time sitting compared to male students. These results align with the observations of Strain et al. (2024), who conducted a pooled analysis of 507 population-based surveys involving 5.7 million adults worldwide [35]. Their sex-specific comparison showed that females were generally less physically active. Similarly, a cross-sectional study by Espada et al. (2023), which examined sex differences in physical activity among 3060 university students in Madrid, Spain using the IPAQ-SF, found that male students engaged in significantly more vigorous and moderate physical activity—findings that align with the results of our study [47]. These findings underscore the need to consider sex-specific factors when designing interventions aimed at promoting mental health and PA among medical students. Tailored strategies that address the unique challenges faced by female students—such as targeted stress-management programmes, initiatives to encourage regular engagement in vigorous and moderate PA, and fostering supportive academic and social environments—may help mitigate the disproportionate burden observed in this group. Future research should further investigate the mechanisms underlying these gender differences and evaluate the effectiveness of sex-specific interventions in improving both mental health and PA outcomes.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of this study need to be considered. The cross-sectional nature of the research does not allow conclusions about causality between PA and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of these associations, future research—particularly longitudinal studies and randomized controlled trials—is required to clarify the directionality and strength of the relationships between different types of PA and mental health outcomes among medical students.

The use of the IPAQ-SF, a self-report instrument, introduces the possibility of recall bias. Participants may have inaccurately reported their physical activity over the preceding week, which could compromise the reliability and validity of the data. Incorporating objective measures such as accelerometers, pedometers, wearable trackers, or heart rate monitors in future studies could improve the precision of PA assessment [48].

While the DASS-21 is a widely used and validated instrument for assessing mental health symptoms in non-clinical populations, it is not designed to provide clinical diagnoses. The use of symptom severity cut-offs—particularly for mild cases—may contribute to inflated prevalence rates. Self-report measures are also vulnerable to individual interpretation and short-term emotional states. Future research could benefit from incorporating structured clinical interviews conducted by qualified mental health professionals to validate screening results and reduce the risk of misclassification.

Moreover, this study was mainly concerned with PA as a potential correlate of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. While valuable, this narrow scope limits insight into the multifactorial nature of mental health outcomes in this population. Future investigations should adopt a more integrative approach by concurrently examining other potentially relevant variables, including sociodemographic characteristics, sleep quality, dietary habits, substance use, academic workload, coping mechanisms, social support, and recent exposure to stressful life events. Accounting for such factors would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay influencing psychological well-being among medical students.

Finally, the sample was drawn exclusively from the Faculty of Medicine in Osijek, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to medical students at the national level.

5. Conclusions

Medical students exhibited high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, accompanied by insufficient PA. Female students reported higher levels of these psychological symptoms, lower levels of PA, and more time spent sitting compared to their male counterparts. The results indicate that higher levels of sitting time were associated with increased levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, whereas greater engagement in PA—particularly vigorous-intensity activity—was associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety.

Furthermore, the results of this study highlight the need for future research—particularly longitudinal studies and randomized controlled trials on larger samples—to clarify the directionality and strength of the associations between different types of PA and mental health outcomes. Future investigations should also employ objective measures of PA and structured clinical interviews conducted by qualified mental health professionals to validate screening results and minimize the risk of misclassification. Taken together, these findings emphasize the necessity of developing evidence-based interventions aimed at improving mental health and promoting adequate levels of PA across different intensity domains, as well as reducing sedentary time, among future healthcare professionals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/psychiatryint6040124/s1, File S1: Participant Information Sheet; File S2: Consent Form and Questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.V.; Formal analysis, S.V., I.L. and M.H.; Investigation, S.V. and E.K.; Methodology, S.V. and I.L.; Software, I.L.; Writing—original draft, S.V.; Writing—review and editing, S.V., D.D., I.D., I.L., A.P., E.K., S.K. and M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Osijek (Approval code: 2158-61-46-25-123; Approval date: 6 May 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical approval requirements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Daniali, H.; Martinussen, M.; Flaten, M.A. A Global Meta-Analysis of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress before and during COVID-19. Health Psychol. 2023, 42, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, Y.; Han, N.; Huang, H. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of College Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 669119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haruna, U.; Mohammed, A.-R.; Braimah, M. Understanding the Burden of Depression, Anxiety and Stress among First-Year Undergraduate Students. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, G.; Estima, F.; Silva, A.C.; Mota, J.; Martins, C.; Aires, L. Mental Health in Young Adult University Students During COVID-19 Lockdown: Associations with Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviors and Sleep Quality. IJERPH 2025, 22, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yang, C.; Wang, J.; Sui, X.; Sun, W.; Wang, Y. Factors Affecting Psychological Health and Career Choice among Medical Students in Eastern and Western Region of China after COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1081360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.S.; Wong, C.C.; Ng, K.W.; Bostanudin, M.F.; Tan, S.F. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among University Students in Selangor, Malaysia during COVID-19 Pandemics and Their Associated Factors. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Garni, A.M.; Shati, A.A.; Almonawar, N.A.; Alamri, G.M.; Alasmre, L.A.; Saad, T.N.; Alshehri, F.M.; Hammouda, E.A.; Ghazy, R.M. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among Students Enrolled at King Khalid University: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Torre, M.; Segal, J.B.; Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quek, T.T.-C.; Tam, W.W.-S.; Tran, B.X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Ho, C.S.-H.; Ho, R.C.-M. The Global Prevalence of Anxiety Among Medical Students: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira De Sousa, J.; Moreira, C.A.; Telles-Correia, D. Anxiety, Depression and Academic Performance: A Study Amongst Portuguese Medical Students Versus Non-Medical Students. Acta Med. Port. 2018, 31, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSamhori, J.F.; Kakish, D.R.K.; AlSamhori, A.R.F.; AlSamhori, A.F.; Hantash, N.R.A.; Swelem, A.F.A.; Abu-Suaileek, M.H.A.; Arabiat, H.M.; Altwaiqat, M.A.; Banimustafa, R.; et al. Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia among Medical and Non-Medical Students in Jordan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2024, 31, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, A.A.; Milaat, W.A.; Ramadan, I.K.; Baig, M.; Elmorsy, S.A.; Beyari, G.M.; Halawani, M.A.; Azab, R.A.; Zahrani, M.T.; Khayat, N.K. Depression, Anxiety and Stress among Medical and Non-Medical Students in Saudi Arabia: An Epidemiological Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. NSJ 2021, 26, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasuriya, S.D.; Jorm, A.F.; Reavley, N.J. Perceptions and Intentions Relating to Seeking Help for Depression among Medical Undergraduates in Sri Lanka: A Cross-Sectional Comparison with Non-Medical Undergraduates. BMC Med. Educ. 2015, 15, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidović, S.; Kotromanović, S.; Pogorelić, Z. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Symptoms Among Students in Croatia During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. JCM 2024, 13, 6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidović, S.; Rakić, N.; Kraštek, S.; Pešikan, A.; Degmečić, D.; Zibar, L.; Labak, I.; Heffer, M.; Pogorelić, Z. Sleep Quality and Mental Health Among Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. JCM 2025, 14, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelmann, D.; Pfirrmann, D.; Heller, S.; Dietz, P.; Reichel, J.L.; Werner, A.M.; Schäfer, M.; Tibubos, A.N.; Deci, N.; Letzel, S.; et al. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in University Students–The Role of Gender, Age, Field of Study, Targeted Degree, and Study Semester. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 821703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.P.; Forman, E.M.; Butryn, M.L.; Herbert, J.D. Differential Programming Needs of College Students Preferring Web-Based Versus In-Person Physical Activity Programs. Health Commun. 2018, 33, 1509–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.J.; Ryan, D.J.; Campbell, J.; Hardwicke, J. Self-Reported Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour amongst UK University Students: A Cross-Sectional Case Study. Crit. Public Health 2024, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Meng, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J. Physical Activity, Weight Management, and Mental Health during COVID-19 Lockdown: A Cross-Sectional Study of Healthcare Students in China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, B.C.R.; Menezes-Júnior, L.A.A.D.; De Paula, W.; Chagas, C.M.D.S.; Machado, E.L.; De Freitas, E.D.; Cardoso, C.S.; De Carvalho Vidigal, F.; Nobre, L.N.; Silva, L.S.D.; et al. Sedentary Behavior Is Associated with the Mental Health of University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and Not Practicing Physical Activity Accentuates Its Adverse Effects: Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štefan, L.; Sporiš, G.; Krističević, T.; Knjaz, D. Associations between Sleep Quality and Its Domains and Insufficient Physical Activity in a Large Sample of Croatian Young Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Beckman, E.M.; Ng, N.; Dingle, G.A.; Han, R.; James, K.; Winkler, E.; Stylianou, M.; Gomersall, S.R. Effectiveness of Physical Activity Interventions on Undergraduate Students’ Mental Health: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Promot. Int. 2024, 39, daae054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanjau, M.N.; Möller, H.; Haigh, F.; Milat, A.; Hayek, R.; Lucas, P.; Veerman, J.L. Physical Activity and Depression and Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review of Reviews and Assessment of Causality. AJPM Focus 2023, 2, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrantes, L.C.S.; De Souza De Morais, N.; Gonçalves, V.S.S.; Ribeiro, S.A.V.; De Oliveira Sediyama, C.M.N.; Do Carmo Castro Franceschini, S.; Dos Santos Amorim, P.R.; Priore, S.E. Physical Activity and Quality of Life among College Students without Comorbidities for Cardiometabolic Diseases: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Qual. Life Res. 2022, 31, 1933–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerriero, M.A.; Dipace, A.; Monda, A.; De Maria, A.; Polito, R.; Messina, G.; Monda, M.; Di Padova, M.; Basta, A.; Ruberto, M.; et al. Relationship Between Sedentary Lifestyle, Physical Activity and Stress in University Students and Their Life Habits: A Scoping Review with PRISMA Checklist (PRISMA-ScR). Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talapko, J.; Perić, I.; Vulić, P.; Pustijanac, E.; Jukić, M.; Bekić, S.; Meštrović, T.; Škrlec, I. Mental Health and Physical Activity in Health-Related University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogić Vidaković, M.; Šimić, N.; Poljičanin, A.; Nikolić Ivanišević, M.; Ana, J.; Đogaš, Z. Psychometric Properties of the Croatian Version of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 and Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale-29 in Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021, 50, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.H.; Macfarlane, D.J.; Lam, T.; Stewart, S.M. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF): A Systematic Review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajman, H.; Đapić Štriga, S.; Novak, D. Reliability of the Croatian Short Version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Hrvat. Športskomedicinski Vjesn. 2015, 30, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahrami, H.; Dewald-Kaufmann, J.; Faris, M.A.-I.; AlAnsari, A.M.S.; Taha, M.; AlAnsari, N. Prevalence of Sleep Problems among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Public Health 2020, 28, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-K.; Saragih, I.D.; Lin, C.-J.; Liu, H.-L.; Chen, C.-W.; Yeh, Y.-S. Global Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression among Medical Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strain, T.; Flaxman, S.; Guthold, R.; Semenova, E.; Cowan, M.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C.; Stevens, G.A. National, Regional, and Global Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity among Adults from 2000 to 2022: A Pooled Analysis of 507 Population-Based Surveys with 5·7 Million Participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e1232–e1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.; Michaelides, G.; Totterdell, P. The Impact of Fluctuating Workloads on Well-Being and the Mediating Role of Work−nonwork Interference in This Relationship. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; Skodda, S.; Muth, T.; Angerer, P.; Loerbroks, A. Stressors and Resources Related to Academic Studies and Improvements Suggested by Medical Students: A Qualitative Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wunsch, K.; Kienberger, K.; Niessner, C. Changes in Physical Activity Patterns Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. IJERPH 2022, 19, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Friedenreich, C.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lee, I.-M. Physical Inactivity and Non-Communicable Disease Burden in Low-Income, Middle-Income and High-Income Countries. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blond, K.; Brinkløv, C.F.; Ried-Larsen, M.; Crippa, A.; Grøntved, A. Association of High Amounts of Physical Activity with Mortality Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noetel, M.; Sanders, T.; Gallardo-Gómez, D.; Taylor, P.; Del Pozo Cruz, B.; Van Den Hoek, D.; Smith, J.J.; Mahoney, J.; Spathis, J.; Moresi, M.; et al. Effect of Exercise for Depression: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. BMJ 2024, 384, e075847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Li, L.; Gan, Y.; Wang, C.; Jiang, H.; Cao, S.; Lu, Z. Sedentary Behaviors and Risk of Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, M.S.; Walter, E.E.; Swann, C. Sedentary Behaviour and Risk of Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 242, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuelvas-Olmos, C.R.; Sánchez-Vidaña, D.I.; Cortés-Álvarez, N.Y. Gender-Based Analysis of the Association Between Mental Health, Sleep Quality, Aggression, and Physical Activity Among University Students During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Psychol. Rep. 2023, 126, 2212–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, T.; Kuang, J.; Herold, F.; Ludyga, S.; Li, J.; Hall, D.L.; Taylor, A.; Healy, S.; Yeung, A.S.; et al. The Roles of Exercise Tolerance and Resilience in the Effect of Physical Activity on Emotional States among College Students. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2022, 22, 100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelleli, H.; Ben Aissa, M.; Kaddech, N.; Saidane, M.; Guelmami, N.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Bonsaksen, T.; Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Dergaa, I. Examining the Interplay between Physical Activity, Problematic Internet Use and the Negative Emotional State of Depression, Anxiety and Stress: Insights from a Moderated Mediation Path Model in University Students. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada, M.; Romero-Parra, N.; Bores-García, D.; Delfa-De La Morena, J.M. Gender Differences in University Students’ Levels of Physical Activity and Motivations to Engage in Physical Activity. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.T.; Kling, S.R.; Salata, M.J.; Cupp, S.A.; Sheehan, J.; Voos, J.E. Wearable Performance Devices in Sports Medicine. Sports Health A Multidiscip. Approach 2016, 8, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).