Not All Bad: A Laboratory Experiment Examining Viewing Images of Nature on Instagram Can Improve Wellbeing and Positive Emotions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Finding Images on Instagram

1.2. The Benefits of Nature

1.3. Theoretical Background

1.4. Authentic vs. Artificial Nature Experiences

1.5. Mechanisms for Improving Wellbeing

1.6. Changing Behaviour

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Design

2.3. Stimuli and Images

2.4. Procedure

“That is the end of this part of the experiment, and you will receive your credit for participating. We also have some additional survey studies that we need to be completed. These are not done here, they are sent to your email address. You do not have to complete these. Moreover, there is no payment for doing these—you do not receive extra credit. If you choose to complete some, you will be taken to another screen to enter your contact details. However, your answers to the current study will not be linked with your contact details. That is, we will not know how many surveys you have chosen to do, including zero. You will receive your credit for the current study regardless of your choice. Click below to proceed”

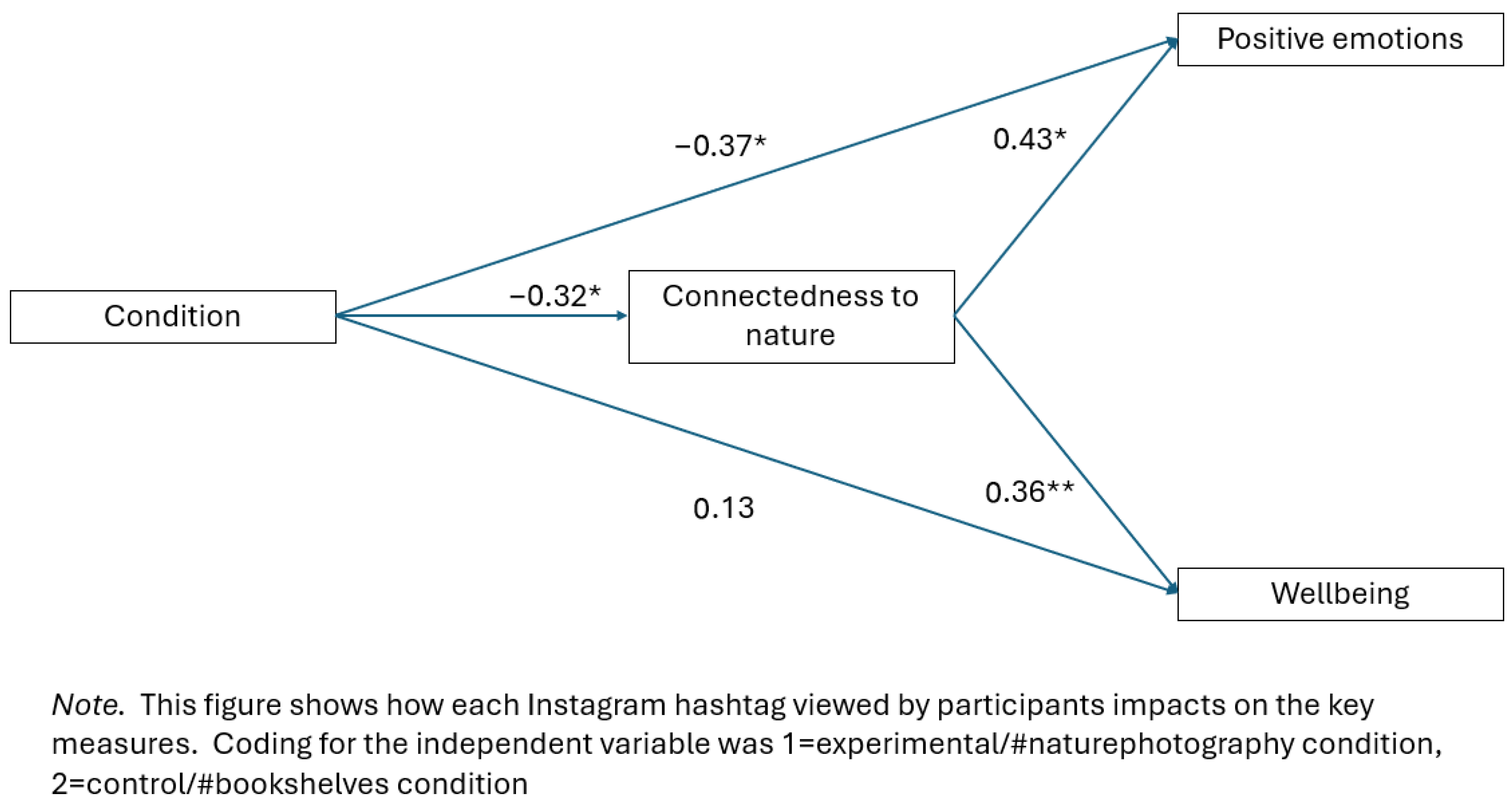

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Fitting the Findings into Existing Theory

4.3. Future Work and Methodological Issues

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Use of Generative AI

References

- McLachlan, S. 2024 Instagram Demographics: Top User Stats for Your Strategy. Available online: https://blog.hootsuite.com/instagram-demographics/ (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Faelens, L.; Hoorelbeke, K.; Cambier, R.; Put, J.; Van de Putte, E.; De Raedt, R.; Koster, E.H.W. The Relationship between Instagram Use and Indicators of Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2021, 4, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naslund, J.A.; Bondre, A.; Torous, J.; Aschbrenner, K.A. Social Media and Mental Health: Benefits, Risks, and Opportunities for Research and Practice. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2020, 5, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perloff, R.M.; Romer, D.; Cornwell, B. Social Media Effects on Young Women’s Body Image Concerns: Theoretical Perspectives and an Agenda for Research. Sex Roles 2017, 71, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Vartanian, L.R.; Halliwell, E. Appearance Comparison and Other Appearance-Related Influences on Body Dissatisfaction in Everyday Life. Body Image 2015, 12, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Nesi, J.; Prinstein, M.J. Instagram Use, Loneliness, and Social Comparison Orientation: Interact and Browse on Social Media, but Don’t Compare. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 703–708. [Google Scholar]

- Trifiro, B.M.; Prena, K. Active Instagram Use and Its Association with Self-Esteem and Well-Being. Technol. Mind Behav. 2021, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondragon, N.I.; Munitis, A.E.; Txertudi, M.B. The Breaking of Secrecy: Analysis of the Hashtag #MeTooInceste Regarding Testimonies of Sexual Incest Abuse in Childhood. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 123, 105412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.; Kim, A.D.; Smaldino, P.E. Hashtags as Signals of Political Identity: #BlackLivesMatter and #AllLivesMatter. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286524. [Google Scholar]

- Reif, A.; Miller, I.; Taddicken, M. “Love the Skin You‘re In”: An Analysis of Women’s Self-Presentation and User Reactions to Selfies Using the Tumblr Hashtag #bodypositive. Mass Commun. Soc. 2022, 26, 1038–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Skibins, J.C.; Das, B.M.; Schuler, G. Digital Modalities, Nature, and Quality of Life: Mental Health and Conservation Benefits of Watching Bear Cams. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2022, 28, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, S.; Aichinger, I.; Swami, V. The Impact of Nature Exposure on Body Image and Happiness: An Experience Sampling Study. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 32, 870–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudimac, S.; Sale, V.; Kühn, S. How Nature Nurtures: Amygdala Activity Decreases as the Result of a One-Hour Walk in Nature. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 4446–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreitzer, M.J. Wellbeing at the Workplace: The Urgency and Opportunity. In Innovative Staff Development in Healthcare; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A Systematic Review of Evidence for the Added Benefits to Health of Exposure to Natural Environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, E.A.; Estes, D. The Effect of Contact with Natural Environments on Positive and Negative Affect: A Meta-Analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmin-Pui, L.S.; Griffiths, A.; Roe, J.; Heaton, T.; Cameron, R. Why Garden?—Attitudes and the Perceived Health Benefits of Home Gardening. Cities 2021, 112, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Lin, B.B.; Dean, J.; Barber, E.; Fuller, R.A. Health Benefits from Nature Experiences Depend on Dose. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackey, N.Q.; Tysor, D.A.; McNay, G.D.; Joyner, L.; Baker, K.H.; Hodge, C. Mental Health Benefits of Nature-Based Recreation: A Systematic Review. Ann. Leis. Res. 2021, 24, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Lu, S. A Systematic Review of Evidence of Additional Health Benefits from Forest Exposure. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 212, 104123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974; ISBN 0-13-925248-7. [Google Scholar]

- Asgarzadeh, M.; Lusk, A.; Koga, T.; Hirate, K. Measuring Oppressiveness of Streetscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thach, T.-Q.; Mahirah, D.; Sauter, C.; Roberts, A.C.; Dunleavy, G.; Nazeha, N.; Rykov, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Christopoulos, G.I.; Soh, C.-K.; et al. Associations of Perceived Indoor Environmental Quality with Stress in the Workplace. Indoor Air 2020, 30, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratman, G.N.; Anderson, C.B.; Berman, M.G.; Cochran, B.; de Vries, S.; Flanders, J.; Folke, C.; Frumkin, H.; Gross, J.J.; Hartig, T.; et al. Nature and Mental Health: An Ecosystem Service Perspective. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, M.P.; DeVille, N.V.; Elliott, E.G.; Schiff, J.E.; Wilt, G.E.; Hart, J.E.; James, P. Associations between Nature Exposure and Health: A Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouso, S.; Borja, Á.; Fleming, L.E.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; White, M.P.; Uyarra, M.C. Contact with Blue-Green Spaces during the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown Beneficial for Mental Health. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; He, J.; Chen, J.; Larsen, L.; Wang, H. Perceived Green at Speed: A Simulated Driving Experiment Raises New Questions for Attention Restoration Theory and Stress Reduction Theory. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 296–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brymer, E.; Araújo, D.; Davids, K.; Pepping, G.J. Conceptualizing the Human Health Outcomes of Acting in Natural Environments: An Ecological Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasca, L.; Carrus, G.; Loureiro, A.; Navarro, Ó.; Panno, A.; Tapia Follen, C.; Aragonés, J.I. Connectedness and Well-being in Simulated Nature. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2021, 14, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, N.L.; Elliott, L.R.; Bethel, A.; White, M.P.; Dean, S.G.; Garside, R. Indoor Nature Interventions for Health and Wellbeing of Older Adults in Residential Settings: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2020, 60, e184–e199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; White, M.P.; Hunt, A.; Richardson, M.; Pahl, S.; Burt, J. Nature Contact, Nature Connectedness and Associations with Health, Wellbeing and pro-Environmental Behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.T.; Leung, A.K.-Y.; Chan, S.H.M. Through the Lens of a Naturalist: How Learning about Nature Promotes Nature Connectedness via Awe. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 92, 102069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehl, P.; White, M.P.; Vitale, V.; Pahl, S.; Elliott, L.R.; Fian, L.; Van Den Bosch, M. From Childhood Blue Space Exposure to Adult Environmentalism: The Role of Nature Connectedness and Nature Contact. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 93, 102225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylstra, M.J.; Knight, A.T.; Esler, K.J.; Le Grange, L.L.L. Connectedness as a Core Conservation Concern: An Interdisciplinary Review of Theory and a Call for Practice. Springer Sci. Rev. 2014, 2, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza-Terán, G.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Fraijo-Sing, B.; Borbón-Mendívil, D.; Poggio, L. Impact of Contact with Nature on the Wellbeing and Nature Connectedness Indicators After a Desertic Outdoor Experience on Isla Del Tiburon. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 864836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Dopko, R.L.; Zelenski, J.M. The Relationship between Nature Connectedness and Happiness: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakir-Demir, T.; Berument, S.K.; Sahin-Acar, B. The Relationship between Greenery and Self-Regulation of Children: The Mediation Role of Nature Connectedness. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Hussain, Z.; Griffiths, M.D. Problematic Smartphone Use, Nature Connectedness, and Anxiety. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A.M. Some Ways in Which Positive Affect Influences Decision Making and Problem Solving. In Handbook of Emotions; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 548–573. [Google Scholar]

- Forgas, J.P. The Influence of Affect on Higher Level Cognition: A Review of Research on Interpretation, Judgement, Decision Making and Reasoning. Cogn. Emot. 2011, 25, 561–595. [Google Scholar]

- Kogut, T. The Socializing Effect of Observing Another’s Helping Behavior. Soc. Influ. 2016, 11, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, C.D.; Powell, A.A. Altruism and Prosocial Behavior. In Handbook of Psychology: Vol. 5. Personality and Social Psychology; Weiner, I.B., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 463–484. [Google Scholar]

- Martela, F.; Ryan, R.M. Helping Others Makes Me Happy: The Influence of Generosity and Social Interest on Subjective Well-Being. J. Individ. Differ. 2015, 36, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sabato, H.; Kogut, T. Happy to Help—If It’s Not Too Sad: The Effect of Mood on Helping Identifiable and Unidentifiable Victims. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haver, A.; Akerjordet, K.; Caputi, P.; Furunes, T.; Magee, C. Measuring Mental Well-Being: A Validation of the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale in Norwegian and Swedish. Scand. J. Public Health 2015, 43, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Franz, C.M. A Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Measure of Individuals’ Feeling in Community with Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D. Altruism in Humans; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, T.-Y.; Li, J.; Jia, H.; Xie, X. Helping Others, Warming Yourself: Altruistic Behaviors Increase Warmth Feelings of the Ambient Environment. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macready, H. [SOLVED] Instagram Algorithm Tips for 2024. Available online: https://blog.hootsuite.com/instagram-algorithm/ (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; SAGE: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4462-7458-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Delle, F.A.; Clayton, R.B.; Jordan Jackson, F.F.; Lee, J. Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram: Simultaneously Examining the Association between Three Social Networking Sites and Relationship Stress and Satisfaction. Psychol. Pop. Media 2023, 12, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Evans, M.J.; Tsuchiya, K.; Fukano, Y. A Room with a Green View: The Importance of Nearby Nature for Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ecol. Appl. 2021, 31, e2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, R.O. Effects of Therapeutic Gardens in Special Care Units for People with Dementia: Two Case Studies. J. Hous. Elder. 2007, 21, 117–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, A.R.; Winterbottom, D. Nearby Nature and Long-Term Care Facility Residents: Benefits and Design Recommendations. J. Hous. Elder. 2006, 19, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.; Turner, M.; Udell, J. Add a Comment … How Fitspiration and Body Positive Captions Attached to Social Media Images Influence the Mood and Body Esteem of Young Female Instagram Users. Body Image 2020, 33, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavis, A.; Winter, R. #Online harms or benefits? An ethnographic analysis of the positives and negatives of peer-support around self-harm on social media. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 842–854. [Google Scholar]

- Mendini, M.; Peter, P.C.; Maione, S. The Potential Positive Effects of Time Spent on Instagram on Consumers’ Gratitude, Altruism, and Willingness to Donate. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 143, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vente, T. Snapchat Story—I Need a Heart Transplant: Benefits of Social Media Use in Serious Illness. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 73, 599–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassenzahl, M.; Tractinsky, N. User Experience—A Research Agenda. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2006, 25, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, H.L.; Toms, E.G. What Is User Engagement? A Conceptual Framework for Defining User Engagement with Technology. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2008, 59, 938–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, E.; Cotter, K.; Cho, J. Explanations as Mechanisms for Supporting Algorithmic Transparency. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, A.M.; Baumgartner, S.E.; Kühne, R.; Peter, J. The Effects of Social Information on the Enjoyment of Online Videos: An Eye Tracking Study on the Role of Attention. Media Psychol. 2021, 24, 214–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, L.; Bogomolova, S.; Kennedy, R.; Nenycz-Thiel, M.; Bellman, S. A Dual-process Model of How Incorporating Audio-visual Sensory Cues in Video Advertising Promotes Active Attention. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, S.E. Sacrifice Is a Step beyond Convenience: A Review of Convenience Sampling in Psychological Research in Africa. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2021, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Kanter, P.E.; Garrido, L.E.; Moretti, L.S.; Medrano, L.A. A Modern Network Approach to Revisiting the Positive and Negative Affective Schedule (PANAS) Construct Validity: Journal of Clinical Psychology. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 2370–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Finkenauer, C.; Vohs, K.D. Bad Is Stronger than Good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 323–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaish, A.; Grossmann, T.; Woodward, A. Not All Emotions Are Created Equal: The Negativity Bias in Social-Emotional Development. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, L.A.; Dovidio, J.F.; Piliavin, J.A.; Schroeder, D.A. Prosocial Behavior: Multilevel Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.D.; Larson, L.R.; Collado, S.; Cloutier, S.; Profice, C.C. Gender Differences in Connection to Nature, Outdoor Preferences, and Nature-Based Recreation Among College Students in Brazil and the United States. Leis. Sci. 2023, 45, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, I.; Yasmeen, B.; Nadeem, M.; Ahmad, N. Filtered Reality: Exploring Gender Differences in Instagram Use, Social Conformity Pressure, and Regret among Young Adults. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2024, 34, 1153–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noon, E.J.; Schuck, L.A.; Guțu, S.M.; Şahin, B.; Vujović, B.; Aydın, Z. To Compare, or Not to Compare? Age Moderates the Relationship between Social Comparisons on Instagram and Identity Processes during Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood. J. Adolesc. 2021, 93, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelenski, J.M.; Nisbet, E.K. Happiness and Feeling Connected: The Distinct Role of Nature Relatedness. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stiff, C.; Orchard, L.J. Not All Bad: A Laboratory Experiment Examining Viewing Images of Nature on Instagram Can Improve Wellbeing and Positive Emotions. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040117

Stiff C, Orchard LJ. Not All Bad: A Laboratory Experiment Examining Viewing Images of Nature on Instagram Can Improve Wellbeing and Positive Emotions. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(4):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040117

Chicago/Turabian StyleStiff, Christopher, and Lisa J. Orchard. 2025. "Not All Bad: A Laboratory Experiment Examining Viewing Images of Nature on Instagram Can Improve Wellbeing and Positive Emotions" Psychiatry International 6, no. 4: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040117

APA StyleStiff, C., & Orchard, L. J. (2025). Not All Bad: A Laboratory Experiment Examining Viewing Images of Nature on Instagram Can Improve Wellbeing and Positive Emotions. Psychiatry International, 6(4), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6040117