Interns’ Abuse Across the Healthcare Specialties in Saudi Arabian Hospitals and Its Effects on Their Mental Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Size

- Interns of the healthcare specialties (medical, dental, nursing, and pharmacy);

- Agree to participate;

- Both females and males;

- Residing in Saudi Arabia.

- Incomplete questionnaires will be excluded;

- Participants who refused to participate would be ineligible.

2.2. Sampling Method

2.3. Data Collection and Management

- The first section focused on sociodemographic information, including age, gender, major, and college.

- The second section assessed the frequency with which participants perceived themselves to have experienced abuse, the source of abuse, and the type of abuse (verbal abuse, physical assault, academic aggression, sexual abuse, and gender discrimination). Each item categorizes abuse into distinct domains to allow for granular analysis.

- The third section explored whether students reported mistreatment, assessed the frequency of reporting experienced abuse, the reasons for non-reporting of perceived abuse (investigated barriers to reporting abuse, including the following: lack of awareness or recognition of abuse, fear of consequences (e.g., grades, professional retaliation), distrust in confidentiality or fairness of reporting processes, belief that reporting is ineffective or burdensome, and personal coping strategies like avoidance or self-resolution), and the participants’ reactions to the abuse.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Intern Demographics

3.2. Prevalence and Types of Harassment and Discrimination

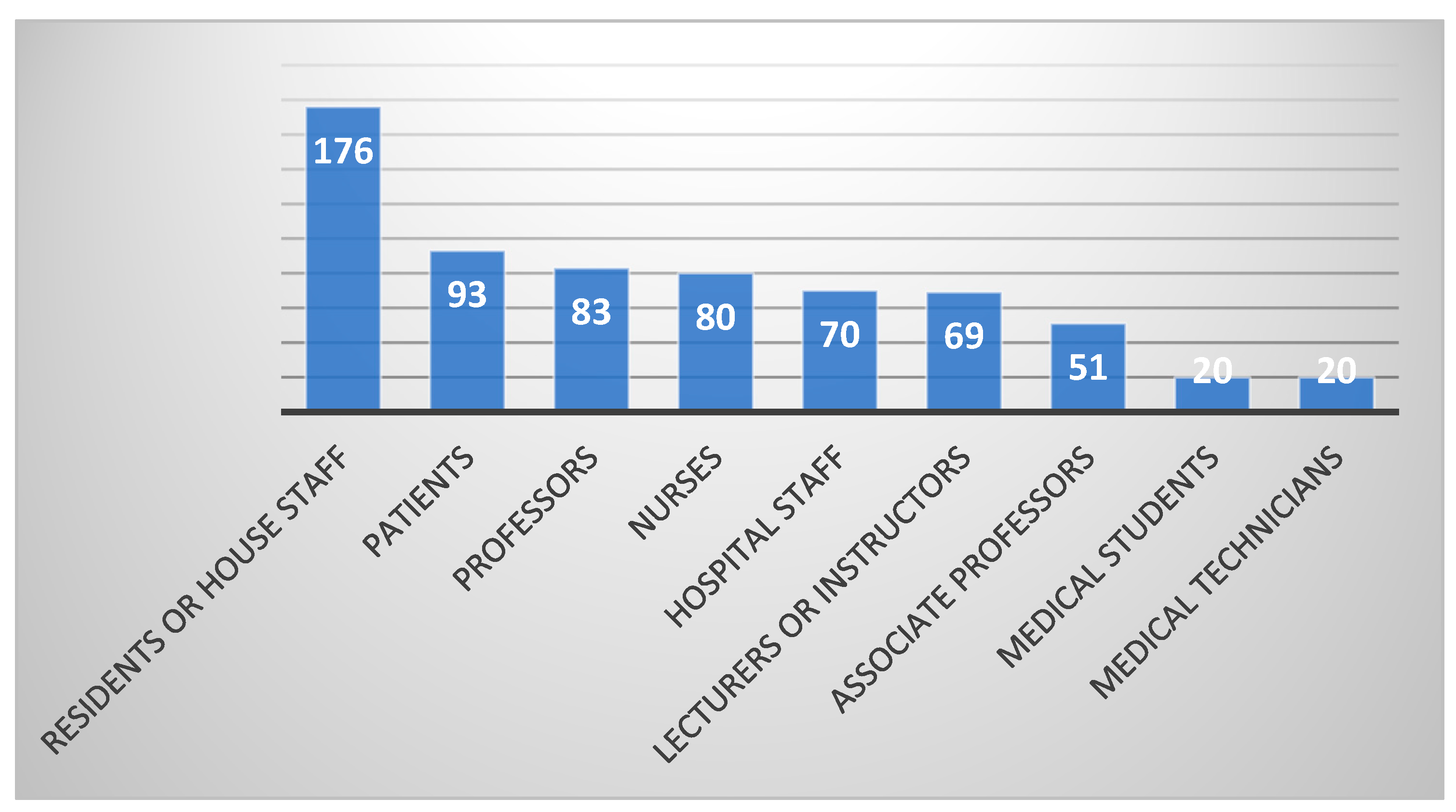

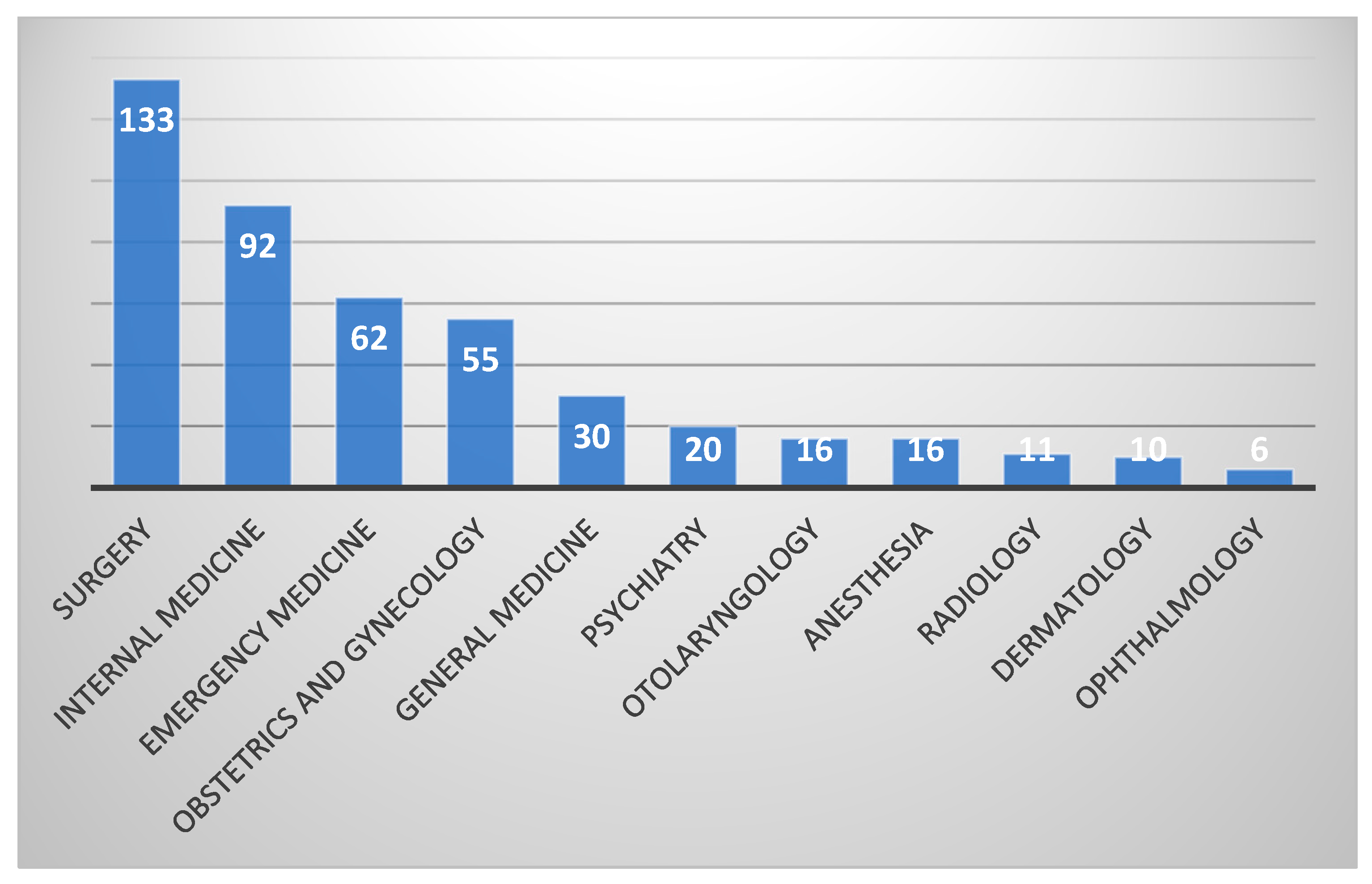

3.3. Perpetrators and Departments of Harassment and Discrimination

3.4. Attitude Towards Different Types of Harassment

3.5. Mental Health (DASS) of the Interns

3.5.1. Mental Health Differences Between Male and Female Interns

3.5.2. Gender Differences in Specific Aggressive Behaviors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johns, S.; Hydle, I.; Aschjem, Ø. The Act of Abuse: A Two-Headed Monster of Injury and Offense. J. Elder Abuse Negl. 1991, 3, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segen, J.C. The Dictionary of Modern Medicine; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-1-85070-321-1. [Google Scholar]

- Boudrias, J.-S.; Roberge, V.; Sénéchal, C.; Brunet, L.; Morin, D. Toutes les formes d’abus en milieu de travail ont-elles les mêmes incidences sur la santé des travailleurs? Hum. Organ. 2023, 7, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuil, B.; Atasayi, S.; Molendijk, M.L. Workplace Bullying and Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis on Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Kong, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, A.; Xie, Q.; Gao, F.; Luan, X.; Zhuang, X.; Du, C.; et al. Psychological Workplace Violence and Its Influence on Professional Commitment among Nursing Interns in China: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1148105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Lu, D.; Luo, Z.; Xu, M.; Sun, L.; Hu, S. Characteristics of Workplace Violence, Responses and Their Relationship with the Professional Identity among Nursing Students in China: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Gan, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, L.; Dwyer, R.; Lu, K.; Yan, S.; Sampson, O.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; et al. Prevalence of Workplace Violence against Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 76, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banakhar, M.; Alzahrani, M.; Essa, A.O.; Al-dhahry, A.F.; Batwa, R.F.; Salem, R.S. Verbal Abuse Facing Saudi Nurses during Internship Program. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2021, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, R.; Tawfiq, R.; Barabie, S. Interns’ perceived abuse during their undergraduate training at King Abdul Aziz University. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2014, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahmari, A.; Alotaibi, T.; Al-Arfaj, G.; Kofi, M. Workplace Bullying among Residents in Saudi Board Training Programs of All Specialties in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 2017–2018 Prevalence, Influencing Factors and Consequences: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Adv. Community Med. 2020, 3, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuainain, H.M.; Alqurashi, M.M.; Alsadery, H.A.; Alghamdi, T.A.; Alghamdi, A.A.; Alghamdi, R.A.; Albaqami, T.A.; Alghamdi, S.M. Workplace Bullying in Surgical Environments in Saudi Arabia: A Multiregional Cross-Sectional Study. J. Fam. Community Med. 2022, 29, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albajjar, M.A.; Bakarman, M.A. Prevalence and Correlates of Depression among Male Medical Students and Interns in Albaha University, Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 1889–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rautio, A.; Sunnari, V.; Nuutinen, M.; Laitala, M. Mistreatment of University Students Most Common during Medical Studies. BMC Med. Educ. 2005, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maida, A.M.; Vásquez, A.; Herskovic, V.; Calderón, J.L.; Jacard, M.; Pereira, A.; Widdel, L. A Report on Student Abuse during Medical Training. Med. Teach. 2003, 25, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, D.F. Bullying in Medical Schools. BMJ 2006, 333, 0610357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, E.; Carrera, J.S.; Stratton, T.; Bickel, J.; Nora, L.M. Experiences of Belittlement and Harassment and Their Correlates among Medical Students in the United States: Longitudinal Survey. BMJ 2006, 333, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, D.C., Jr.; Daugherty, S.R.; Eckenfels, E.J. Student Perceptions of Mistreatment and Harassment during Medical School. A Survey of Ten United States Schools. West. J. Med. 1991, 155, 140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.S. 318 Verbal and Physical Abuse against Jordanian Nurses in the Work Environment. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2012, 18, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, H.A. Bullying among Medical Students in a Saudi Medical School. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daugherty, S.R.; Baldwin, J.; DeWitt, C.; Rowley, B.D. Learning, Satisfaction, and Mistreatment During Medical Internship: A National Survey of Working Conditions. JAMA 1998, 279, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscarello, R.; Margittai, K.J.; Rossi, M. Differences in Abuse Reported by Female and Male Canadian Medical Students. CMAJ 1994, 150, 357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silver, H.K.; Glicken, A.D. Medical Student Abuse: Incidence, Severity, and Significance. JAMA 1990, 263, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shdaifat, E.A.; AlAmer, M.M.; Jamama, A.A. Verbal Abuse and Psychological Disorders among Nursing Student Interns in KSA. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2020, 15, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fnais, N.; al-Nasser, M.; Zamakhshary, M.; Abuznadah, W.; Al-Dhukair, S.; Saadeh, M.; Al-Qarni, A.; Bokhari, B.; Alshaeri, T.; Aboalsamh, N.; et al. Prevalence of Harassment and Discrimination among Residents in Three Training Hospitals in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 2013, 33, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Averbuch, T.; Eliya, Y.; Van Spall, H.G.C. Systematic Review of Academic Bullying in Medical Settings: Dynamics and Consequences. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata-Kobayashi, S.; Maeno, T.; Yoshizu, M.; Shimbo, T. Universal Problems during Residency: Abuse and Harassment. Med. Educ. 2009, 43, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, E.; Zhao, Z.; Fang, Y.; Cleary, J.L.; Viglianti, E.M.; Sen, S.; Guille, C. Trends in Sexual Harassment Prevalence and Recognition During Intern Year. JAMA Health Forum. 2024, 5, e240139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viglianti, E.M.; Oliverio, A.L.; Pereira-Lima, K.; Frank, E.; Meeks, L.M.; Sen, S.; Bohnert, A.S.B. Variation by Institution in Sexual Harassment Experiences Among US Medical Interns. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2349129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlMulhim, A.A.; Nasir, M.; AlThukair, A.; AlNasser, M.; Pikard, J.; Ahmer, S.; Ayub, M.; Elmadih, A.; Naeem, F. Bullying among Medical and Nonmedical Students at a University in Eastern Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2018, 25, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komaromy, M.; Bindman, A.B.; Haber, R.J.; Sande, M.A. Sexual Harassment in Medical Training. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubitz, R.M.; Nguyen, D.D. Medical Student Abuse during Third-Year Clerkships. JAMA 1996, 275, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bommarito, S.; Hughes, M. Intern Mental Health Interventions. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilchez-Cornejo, J.; Viera-Morón, R.D.; Larico-Calla, G.; Alvarez-Cutipa, D.C.; Sánchez-Vicente, J.C.; Taminche-Canayo, R.; Carrasco-Farfan, C.A.; Palacios-Zegarra, A.A.; Mendoza-Flores, C.; Quispe-López, P.; et al. Depression and Abuse During Medical Internships in Peruvian Hospitals. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. Engl. Ed. 2020, 49, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sociodemographic | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male Female | 149 (32.2) 314 (67.8) |

| Age (years) | 20–30 | 463 (100) |

| Internship province | Riyadh Eastern Aseer Mekkah Al-Baha Al-Qassim Others | 102 (22) 151 (32.6) 52 (11.2) 49 (10.5) 16 (3.5) 10 (2.2) 83 (18) |

| Major | Medicine Pharmacy Dentistry Nursing Other | 281 (60.7) 69 (14.9) 53 (11.5) 55 (11.9) 5 (1) |

| Variable | Male N (%) | Female N (%) | Total (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal aggression | 77 (31.6) | 167 (68.4) | 244 (52.7) | 0.8 |

| Physical assault | 16 (29.1) | 39 (70.9) | 55 (11.9) | 0.6 |

| Academic aggression (e.g., giving assignments as punishment, threatening to get a bad grade without justification, unjustifiably threatening to fail a class or during clinical training, facing malicious or unfair competition, and making negative statements about becoming a health professional or continuing in the health field) | 72 (29) | 176 (71) | 248 (53.6) | 0.1 |

| Sexual Assault | ||||

| Sexual comments | 16 (23.5) | 52 (76.5) | 68 (14.7) | 0.09 |

| Unwanted attention | 28 (20.9) | 106 (79.1) | 134 (29) | 0.001 * |

| Unwelcome verbal advances (e.g., expressions of sexual interest or sexual inquiries) | 24 (22.6) | 82 (77.4) | 106 (23) | 0.02 * |

| Unwanted, persistent personal invitations | 17 (20.7) | 65 (79.3) | 82 (17.7) | 0.014 * |

| Unwelcome explicit proposition | 18 (23.4) | 59 (76.6) | 77 (16.6) | 0.07 |

| Offensive material display (e.g., display of offensive sexual pictures or cartoons) | 9 (22.5) | 31 (77.5) | 40 (8.6) | 0.2 |

| Offensive body language (e.g., repeated leering; standing too close) | 27 (19.1) | 114 (80.9) | 141 (30.4) | 0.001 * |

| Unwanted physical advances | 17 (20.7) | 65 (79.3) | 82 (17.7) | 0.01 * |

| Sexual bribery (e.g., offers of better grades, other advantages, or threats in exchange for sexual favors) | 8 (21.1) | 30 (78.9) | 38 (8.2) | 0.1 |

| Gender Discrimination | ||||

| Denied or restricted the opportunity to examine patients | 55 (35.7) | 99 (64.3) | 154 (33.3) | 0.3 |

| Denied the opportunity to participate in a medical technique | 44 (32.1) | 93 (67.9) | 137 (29.6) | 0.9 |

| Assignments made based on gender | 70 (31.7) | 151 (68.3) | 221 (47.7) | 0.8 |

| Denied attending a conference or meeting | 23 (31.9) | 49 (68.1) | 72 (15.5) | 0.9 |

| Restriction of career choice | 28 (20.7) | 107 (79.3) | 135 (29.2) | 0.001 * |

| Variable | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Did not recognize the experience as abuse at the time. | 81 (8.9) | |

| - Considered the experience abusive but judged it not significant enough to report. | 98 (10.7) | |

| - Did not think reporting would accomplish anything. | 133 (14.5) | |

| - Considered reporting more troublesome than it was worth. | 40 (4.4) | |

| - Dealt with the problem directly. | 45 (5) | |

| - Did not know to whom to report. | 63 (6.9) | |

| - Fearful reporting would adversely affect evaluation. | 16 (1.7) | |

| - The mistreatment stopped. | 28 (3) | |

| - Fearful reporting would not be kept confidential. | 51 (5.6) | |

| - Did not think the problem would be dealt with fairly. | 19 (2) | |

| - Did not want to be labeled. | 21 (2.3) | |

| - Fearful of not being believed. | 63 (7) | |

| - Concerned about being blamed. | 15 (1.6) | |

| - Did not want to think about the mistreatment further. | 13 (1.4) | |

| - Fearful reporting would negatively influence a professional career. | 45 (4.9) | |

| - Despaired of the current learning situation during the apprenticeship. | 24 (2.6) | |

| - None of the above. | 160 (17.5) | |

| If you experienced mistreatment, what was your reaction to this? mistreatment? (Select one or more) (responses = 791). | Anger | 127 (19) |

| Little impact | 48 (6) | |

| Dismissal of the mistreatment experiences | 45 (5.7) | |

| Diminished eagerness to learn | 119 (15) | |

| Uncomfortable, nervous | 118 (15) | |

| Depressed | 75 (9.5) | |

| Afraid | 65 (8.2) | |

| More eager to learn | 131 (16.5) | |

| Insomnia, loss of appetite | 33 (4.2) | |

| Thought about dropping out | 30 (3.7) | |

| Variable | Depression Mean ± SD | Anxiety Mean ± SD | Stress Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Males | 8.47 ± 10 | 6.5 ± 9 | 8.4 ± 10 |

| Females | 14.8 ± 11.6 | 12.4 ± 11 | 15.3 ± 11.3 |

| p value | 0.02 * | 0.001 * | 0.01 * |

| Reporting the abuse to the authority | |||

| Yes | 12.6 ± 11.7 | 12.5 ± 12.7 | 14.2 ± 11.2 |

| No | 12.8 ± 11.5 | 10.3 ± 10.6 | 13 ± 11.4 |

| p value | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Verbal aggression | |||

| Yes | 15.9 ± 11.6 | 13.6 ± 11.3 | 16.2 ± 11.3 |

| No | 9.3 ± 10.4 | 7 ± 9 | 9.5 ± 10.3 |

| p value | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | 0.001 * |

| Physical assault | |||

| Yes | 18.4 ± 10.6 | 18.4 ± 10.6 | 18.2 ± 9.6 |

| No | 12 ± 11.5 | 9.4 ± 10.4 | 12.4 ± 11.4 |

| p value | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | 0.001 * |

| Academic aggression | |||

| Yes | 16 ± 11.8 | 13.8 ± 11.3 | 16.3 ± 11.3 |

| No | 9 ± 10 | 6.7 ± 8.7 | 9.3 ± 10.2 |

| p value | 0.03 * | 0.001 * | 0.001 * |

| Sexual assault | |||

| Yes | 10.6 ± 11.8 | 7.7 ± 10 | 10.7 ± 11.5 |

| No | 15.4 ± 10.6 | 13.7 ± 11 | 15.8 ± 10.6 |

| p value | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | 0.001 * |

| Gender discrimination | |||

| Yes | 9.16 ± 11 | 6.9 ± 9.9 | 9.5 ± 11.2 |

| No | 15.3 ± 11.2 | 13 ± 10.7 | 15.5 ± 10.8 |

| p value | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | 0.001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alghamdi, F.A.; Alghamdi, B.M.; Alghamdi, A.A.; Alzahrani, M.A.; Qasem, B.A.; Alshehri, A.A.; Aloufi, A.K.; Hakami, M.H.; Ismail, R.I.M.; Hakami, A.H.; et al. Interns’ Abuse Across the Healthcare Specialties in Saudi Arabian Hospitals and Its Effects on Their Mental Health. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030089

Alghamdi FA, Alghamdi BM, Alghamdi AA, Alzahrani MA, Qasem BA, Alshehri AA, Aloufi AK, Hakami MH, Ismail RIM, Hakami AH, et al. Interns’ Abuse Across the Healthcare Specialties in Saudi Arabian Hospitals and Its Effects on Their Mental Health. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(3):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030089

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlghamdi, Farah A., Bushra M. Alghamdi, Atheer A. Alghamdi, Miad A. Alzahrani, Basmah Ahmed Qasem, Atheel Ali Alshehri, Alwaleed K. Aloufi, Mohammed H. Hakami, Rawaa Ismail Mohammed Ismail, Alaa H. Hakami, and et al. 2025. "Interns’ Abuse Across the Healthcare Specialties in Saudi Arabian Hospitals and Its Effects on Their Mental Health" Psychiatry International 6, no. 3: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030089

APA StyleAlghamdi, F. A., Alghamdi, B. M., Alghamdi, A. A., Alzahrani, M. A., Qasem, B. A., Alshehri, A. A., Aloufi, A. K., Hakami, M. H., Ismail, R. I. M., Hakami, A. H., Abdelwahab, A. E., & Alghmdi, S. M. (2025). Interns’ Abuse Across the Healthcare Specialties in Saudi Arabian Hospitals and Its Effects on Their Mental Health. Psychiatry International, 6(3), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030089