Abstract

Introduction: In the literature, depression is a medical condition that is well known and has been studied for decades, yet in clinical practice it often happens that depressive symptoms are confused with structured disorders or complexes. This incorrect interpretation can lead the psychiatrist to choose to make a psychopharmacological prescription, relegating psychotherapy to mere support or in any case reducing its importance, risking making the patient’s symptoms chronic and overloading the healthcare system. Materials and Methods: The literature up to December 2024 was reviewed and 40 articles were included in the review. A pilot study was conducted to verify the effectiveness and validation of the proposed theoretical model. Results: We propose the use of the “Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment” (PDSYA) for the differential diagnosis in disorders with the manifestation of depressive symptoms, to facilitate the correct diagnosis and to reduce interpretative errors, both at a nosographic and therapeutic level. Conclusions: In the pilot study, in the content validity analysis, all items obtained a CVR score greater than the cut-off value, with a minimum score of 0.811. Therefore, all items of the scale were considered essential; also, regarding the relevance of the items in exploring the constructs investigated, optimal values of I-CVI (>0.93) and scale (S-CVI > 0.98) were obtained. Therefore, all items were rated as relevant. The validation study of the model is underway with a representative sample.

1. Introduction

1.1. General and Clinical Profiles

In the literature, depression is a medical condition that has been well known and studied for decades, with a precise nosographic framing based on symptoms [1]. In particular, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, version 5—rev (DSM-5-TR) uses the term “depression” to refer to one of the depressive disorders described in the manual [2]. Based on symptoms (depressed mood for most of the day, marked decrease or loss of interest or pleasure in new or enjoyed activities, psychomotor agitation or slowing down, fatigability, loss or lack of energy/life impetus, physical prostration, anxiety and sleep disorders, significant weight loss without dieting, or significant weight gain, or decreased or increased appetite, psychosomatic disorders and tendency to isolation, loneliness, sedentariness, poor self-care and self-abandonment with decreased social and emotional relationships, suicidality and hopelessness/pessimism), it is possible to identify other forms of depression, such as dysthymic disorder or those with specificity or without [2,3]. Symptoms of depressive spectrum disorders are often comorbid with other mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder [3,4], but they are always related to specific dysfunctional personality patterns [5,6].

Epidemiological estimates consider depressive disorder to be among the highest in incidence in the population, settling it between 5% and 8% of the general population and 15–35% of the psychiatric population, especially in the adult and mature segments [7,8,9].

The etiology of depressive disorders is not yet known, but both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the symptomatology [10]. Heredity determines about half of the etiology (less so in late-onset depression) [11]. Depression is therefore more common among first-degree relatives of depressed patients, and concordance among identical twins is high [12,13]. Other hypotheses point instead to changes in neurotransmitter levels, including abnormal regulation of cholinergic, catecholaminergic (noradrenergic or dopaminergic) glutamatergic, and serotonergic (5-hydroxytryptamine) transmission [14,15,16]. Neuroendocrine dysregulation may be a factor, with particular emphasis on the three axes: hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal, hypothalamus–pituitary–thyroid, and growth hormone–hypothalamus–pituitary. However, it is not yet clear in the literature whether neurotransmitter alterations are necessarily the cause of depressive spectrum disorders or whether they are the consequence of them [17,18,19]. Psychosocial factors, such as work stress and the social reference environment, also seem to be involved [20,21]. Severe existential stresses, particularly separations and losses, generally precede episodes of major depression; however, such events usually do not cause major depression except in individuals predisposed to a mood disorder, and in any case, less resilient and/or anxiety-prone individuals are more likely to develop a depressive disorder [22,23]. The female sex presents a higher risk of suffering from depressive symptoms (net of common causes such as traumatic episodes, negative experiences, and work stress), especially in adulthood and mature age probably due to an etiology combined with the hormonal profile, but in the literature there is not yet a clear position on this profile [24]. Certain drugs, such as corticosteroids, some beta-blockers, interferon, and reserpine, can cause depressive disorders. The abuse of certain substances and illicit substances (e.g., alcohol, amphetamines) can trigger or accompany depression. Toxic effects or withdrawal from substances can cause transient depressive symptoms [25].

The importance of an accurate clinical framework in the manifestations of the depressive spectrum arises from the need to correctly frame the morbid condition to decide on the best clinical approach (whether psychotherapeutic, psychopharmacological or combined) [26,27,28,29,30]. In clinical practice it often happens that depressive symptoms can be misinterpreted and confused with depressive disorders, as they are also present in anxiety disorders, bipolarism, dementia, substance use, and various medical conditions [31,32]. This can happen because the symptomatology is common to several disorders (as it is between bipolar disorder and borderline disorder), but it can also be faked, for personal reasons (to show up sicker, in fictitious disorders or to attract attention) or economic reasons (attainment of a disability pension), even in good faith (in somatizations), and thus the risk of prescribing the wrong drug therapy is very high, thus reducing the importance of psychotherapy or risking chronicizing the patient’s symptoms and overburdening the health care system with unnecessary costs [33,34,35,36].

For this reason, targeted intervention is needed to clarify the boundaries of differential diagnosis, in hypotheses of clinically relevant manifestations with depressive symptoms.

1.2. Objectives

A review was conducted to determine the clinical boundaries of depressive symptoms to aid exact diagnosis and reduce the risk of diagnostic error, both in terms of nosographic framing and treatment. The objective of this discussion is to try to determine whether, in the current state of scientific knowledge, the following research questions can be answered:

- (1)

- Can the difference between depressive symptoms and depressive disorders be determined?

- (2)

- Can a new scale of severity of depressive manifestation be determined with *reasonable* certainty that can fill the current gap in the literature?

- (3)

- Can we propose a model that helps to correctly frame the patient’s clinical condition when *he/she/they present(s) with* depressive symptoms?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Review Questions

Literature was reviewed on Pubmed. To identify the salient aspects, the author focused on the elements that can determine the exact differential diagnosis of disorders presenting with depressive symptoms.

2.2. Materials and Methods

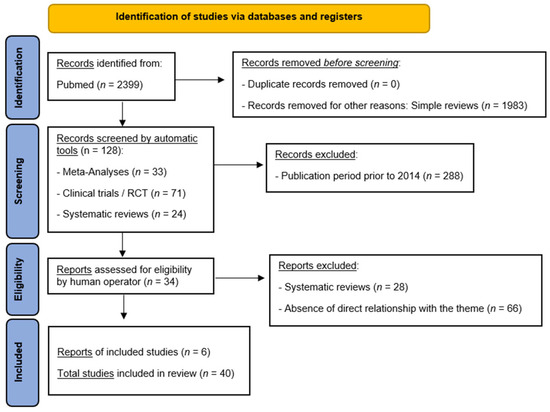

The authors selected systematic reviews, clinical trials, and randomized controlled trials using the keywords “depression disorder” AND “differential diagnosis” and selected 2399 useful results, from January 1971 to December 2024; of these, only 34 were included in the present narrative review paper and concern the last decade of publications. To have a broader and more comprehensive overview of the topic, 6 more publications were selected (in relation to academic manuscripts such as official manuals), for a total of 40 results to enrich the literature present in the introduction. The content of the selected manuscripts did not contribute to the nomenclature and diagnostic criteria of the proposed new model which is instead based on the DSM-5-TR [2] and the Perrotta Integrative Clinical Interviews 3 (PICI-3) [5]. Simple reviews and opinion contributions were excluded because they were not relevant or redundant to this work. The search was limited to English-language articles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart template. Adapted from Matthew J. Page et al., BMJ 2021; 372:n71 [37].

Finally, a pilot study was conducted to verify the effectiveness and validation of the proposed theoretical model, using the method suggested by Kishore et al. [38], based on a power analysis with the outcome indicated in the section relating to the results of the pilot study.

3. Results: “Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment” Proposal

3.1. Can the Difference Between Depressive Symptoms and Depressive Disorder Be Determined?

Yes, it is possible. In literature and clinical practice, the diagnostic criteria are clear and comprehensive with respect to the nosographic figures described. Based on the specific depressive symptoms and their characteristics (duration, intensity, and triggers), the most appropriate diagnostic framing can be determined (Table 1); however, the DSM-5-TR as well as other sources (e.g., the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual—PDM-II or International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision—ICD-11) are not yet able to provide a holistic model that can guarantee the therapist the exact diagnostic framing, without risking the interpretation of depressive symptoms necessarily as a disorder present in nosography but simply as dysfunctional personality traits. Therefore, for the purposes of diagnosis and treatment, it is important to have a tool that can support the therapist in clinical operations.

Table 1.

DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria related to principal depressive disorders.

3.2. Can a New Scale of Severity of Depressive Manifestation Be Determined with *Reasonable* Certainty That Can Fill the Current Gap in Literature?

Currently, no. There are no proposed models in the literature that succeed in determining the degree of functional impairment, except in terms of malaise and distress complained of by the patient. The scale values of the psychometric tests used to diagnose depressive disorder (e.g., the Beck Depression Inventory—BDI, or the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory 2—MMPI-II) are able to investigate the severity of the condition according to a logic of increasing score (the higher the score the greater the dysfunction found), but there is no model capable of organizing the depressive universe in a holistic and structured manner.

3.3. Can We Propose a Model That Helps to Correctly Frame the Patient’s Clinical Condition When *He/She/They Present(s) with* Depressive Symptoms?

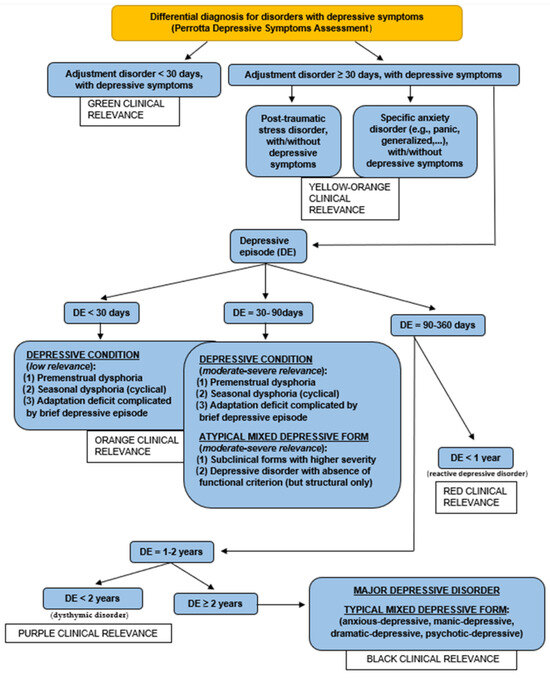

Based on the critical issues encountered in terms of a psychopathological diagnosis and subsequent treatment, it was decided to structure a theory (Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment Theory, PDSYA-t), a model (Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment Model, PDSYA-m), and a scale (Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment Scale, PDSYA-s), which were able to meet this clinical need, offering the therapist theoretical–practical support to correctly diagnose his patient’s psychopathological condition. Figure 2 shows the diagnostic flowchart for the differential diagnosis of disorders with depressive symptoms according to the proposed model. The Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment is described in detail in the following section.

Figure 2.

Diagnostic flow chart for differential diagnosis for disorders with depressive symptoms.

3.4. Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment (PDSYA)

To meet all the corrective needs of the current diagnostic profile of depressive disorders, the “Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment” (PDSYA) is proposed, which has the following technical features (Table 2), among which the model (Table 3) and scale (Table 4) are also defined.

Table 2.

Technical characteristics of the “Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment”.

Table 5.

Perrotta Depressive Symptom Assessment Scale for Therapies (PDSYA-s-t). “Level” represents the increasing scale of representation of psychopathological severity about depressive symptoms. The “color” is the exact corresponding of the levels, in its graphical representation. The “description” is the column for the descriptive listing of the specific level.

Table 3.

Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment Model (PDSYA-m). The “nosographic category” represents the definition of the new nosography. The “type” represents the specific subtype. The “description” is the column for the descriptive listing of the specific level according to the descriptive criteria.

Table 4.

Perrotta Depressive Symptom Assessment Scale (PDSYA-s). “Level” represents the increasing scale of representation of psychopathological severity about depressive symptoms. The “color” is the exact corresponding of the levels, in its graphical representation. The “specificity” is the mathematical result of the summation between 2 physical quantities: intensity (I understood as subjective perception of pervasiveness of depressive symptoms) and frequency (f, understood as the number of daily repetitions of depressive symptoms), according to individual subjective values ranging from 1 (low) to 3 (high). The “description” is the column of the descriptive details.

3.5. Pilot Study to Proceed with the Validation of the Model

From the “Perrotta Depressive Symptom Assessment Model” (PDSYA-m) proposal, a questionnaire was designed and developed with the aim of reducing the risk of diagnostic error of depressive symptoms and framing them in a functional manner with respect to one’s structural personality profile, according to the PICI-3 model, for an age range between 12 years and 70 years. It must be administered by the therapist and cannot be self-administered in any of its parts.

To facilitate the process of classifying depressive symptoms, a questionnaire with progressive questions was developed, divided into three sections: the first (A), with 8 items, relating to preliminary personal and clinical data; the second (B), with 9 items, relating to the severity index of the depressive state (ED), using three different sub-indexes (general dichotomous yes/no response, intensity and frequency perceived by the patient); and the third (C), with 18 progressive response items, relating to the diagnostic classification of depressive symptoms, using the general dichotomous yes/no response index.

The study is underway with a representative population sample, but here we proceed to report the research data on a limited population sample, to proceed with a pilot study to demonstrate the validity of the construct [38].

Based on the seven steps to follow for the development of a questionnaire, the validity analysis data based on the pilot study are reported below. The structured questionnaire was subjected to statistical analysis, using a pilot population sample (36 people, aged 18 to 65 years, 18 males and 18 females; M: 41.5, SD: 13.6).

The power of the sample was tested with a statistical analysis that required a population sample of no less than 24 units.

Therefore, the content validity ratio (CVR) measure was used to assess the relevance of the questionnaire, while the content validity index (CVI) measure was used for representativeness and clarity, as suggested by Kishore et al. [38]. The CVR is a statistical method for establishing content validity, while the CVI is the average CVR for all items included in the final instrument. Appropriate S-CVI values are ≥0.80. For qualitative content validation, the same group was asked two open-ended questions (one concerning the items and one about the administrative procedure): 1. “Is the language form adopted in defining the items described clear and understandable?” 2. “Evaluate the clarity and language form adopted to describe the administration procedure”. These questions were analyzed qualitatively using a thematic content analysis approach, taking into consideration any suggestions for clarification of the language form of the items.

It was administered through a clinical interview lasting 30 min for each participant, during November 2024 and February 2025, recording data in a single form, and reused anonymously and in aggregate.

In the case of content validity, all items scored CVR above the cut-off value, with a minimum score of 0.811.

Therefore, all scale items were considered essential. In addition, regarding the items’ relevance in exploring the investigated constructs, optimal I-CVI (>0.93) and scale (S-CVI > 0.98) values were obtained. Therefore, all items were rated as relevant (Table 6).

Table 6.

Data collection of PDSYA-Q1, according to the scheme of Kishore et al. [38]. The content of the items is indicated in the following Appendix A.

4. Discussion

In clinical practice, the differences between symptoms, conditions, manifestations, and disorders are often confused by practitioners, and it is not uncommon as revealed by the readings that in psychiatry, identification errors related to diagnosis, and consequently treatment, can be made. In addition, there is a marked tendency in psychiatry to prefer drug therapy as the first level of intervention, instead of adhering to psychotherapy, preventing the patient from cognitively intervening on symptoms to promote change. On the other hand, it is well known that drug therapy intervenes on the symptom by trying to limit it or make it disappear, but it is psychotherapy that teaches the patient what to do and how to change the perceptual state with respect to the problem, then finding the solutions [39,40].

Currently, there are no models that can clarify the diagnostic boundaries in the area of depressive manifestation and reduce the risk of misinterpretation of one or more symptoms (e.g., diagnosing depression in a person with a narcissistic covert personality, who tends to use depressive symptoms to blame and attract attention, reinforcing them if he or she succeeds in achieving what is desired). The PDSA thus seeks to fill these interpretive gaps, offering the following correctives to the current clinical approach:

- Allows grading the spectrum of complexity of the depressive manifestation, distinguishing the hypotheses of a depressive condition from that of a depressive disorder, through mixed forms, offering the therapist a flow chart for differential diagnosis and the best type of clinical intervention.

- It allows the exact diagnosis of the nosographic category involved in the investigation to be distinguished using specific structural and functional criteria.

- Allows early intervention even on the mildest or attenuated forms, to facilitate a gradual psychotherapeutic intervention, without necessarily waiting for the strict nosographic criteria of a depressive disorder to be met. Unlike the DSM-5-TR, this model does not distinguish only in categorical terms but also in functional/ dysfunctional terms.

- Allows the severity of depressive manifestation to be graded, based on subjective criteria, in relation to the intensity and frequency of the symptoms themselves.

Systematically defining the differential diagnosis of disorders presenting with depressive symptoms means being able to frame the subject both structurally and functionally, choosing the most appropriate treatment and avoiding letting the therapist decide based on his or her own assumption or subjective interpretation of the patient’s symptomatic experience or only based on the patient’s narrative. It is therefore extremely important to be able to carry out such an operation to give clinical dignity to a clinical manifestation that, to date, has not yet been fully explained and is often diagnosed only in its most severe and disabling forms, chronicizing the patient’s symptomatology and irrational beliefs.

The presence of depressive symptoms cannot simply be traced back to depressive disorders but must be assessed clinically, in the differential diagnosis, to decide on the best diagnosis and treatment most adherent and functional for the patient’s condition. To facilitate the therapist’s work, the Perrotta Depressive Symptom Assessment (PDSYA) tries to reduce the risk of diagnostic error, both in the identification phase of the nosographic condition and in the therapy phase (psychological and pharmacological).

5. Limitations and Future Prospects

This pilot study uses a small but powerful population sample according to the appropriately produced statistical analysis, and this result gives us hope for the outcome of the study that is underway with an adequate and representative population sample. This size currently represents a limitation for the generalization of the results; however, based on the statistical results obtained, we are confident in being able to state that the model has a good chance of being considered valid with the extended study.

In the future, research should focus on the practical requirements of this clinical need, with greater attention to etiological causes, the role of neurotransmitters and neural correlates, the best structural and functional framing of the subject’s personality, and the most appropriate therapy to pursue.

6. Conclusions

The proposal of the new theoretical model of the “Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment”, supported by the questionnaire, has demonstrated in the pilot study a fair content validity considering all the essential and relevant items. The validation study of the model is ongoing with a representative sample, but these results reinforce the hypothesis of its validity being able to generalize its results. This will allow preventive intervention even in attenuated or mild forms of a depressive nature and will allow us to focus on the diagnostic label and therapeutic objectives, reducing the risk of interpretative errors and promoting a better approach and a better resolution of depressive spectrum disorders.

Author Contributions

G.P. is the creator and developer of the theory, model, questionnaire, and scale. He is also the editor of the manuscript. S.E. and I.P. are co-authors and reviewers of the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to Legislative Decree No. 52/2019 link: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2019/06/12/19G00059/sg (accessed on 9 June 2025) and Law No. 3/2018, link: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2018/1/31/18G00019/sg (accessed on 9 June 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical approval requirements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

Perrotta Depressive Symptom Assessment (PDSYA). Perrotta Depressive Symptom Assessment Theory (PDSYA-t). Perrotta Depressive Symptom Assessment Model (PDSYA-m). Perrotta Depressive Symptom Assessment Scale (PDSYA-s). Perrotta Depressive Symptom Assessment Scale for Therapies (PDSYA-s-t). Perrotta Depressive Symptom Assessment Questionnaire (PDSYA-Q1). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, version 5—rev (DSM-5-TR). Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual 2 (PDM-II). International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11). Perrotta Integrative Clinical Interviews 3 (PICI-3). Depressive Disorder (DD). Perrotta Human Emotions Model-2 (PHEM-2).

Appendix A

Table A1.

Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment Questionnaire (PDSYA-Q1).

Table A1.

Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment Questionnaire (PDSYA-Q1).

| Perrotta Depressive Symptoms Assessment Questionnaire (PDSYA-Q-1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SECTION A: Preliminary biographical and clinical data | ||||||

| N | Item | Answer | ||||

| 1 | Name and surname | |||||

| 2 | Date of Birth (Age) | |||||

| 3 | Place of birth | |||||

| 4 | Habitual domicile | |||||

| 5 | Phone/Cel. | |||||

| 6 | ||||||

| 7 | Medical psychophysical history | |||||

| 8 | Drug therapies | |||||

| SECTION B: Depressive State Severity Index (ED) | ||||||

| N | Item | Answer | Intensity—Frequency | Score partial | ||

| 1 | Depressed mood, which consists of external character manifestations in sad, melancholy, passive and negative ways, with respect to circumstances and the socio-environmental context that instead turn out to be positive or in any case neutral, thus risking compromising the functioning of one or more spheres of life (e.g., personal, social, work, affective) |  |  |  | ||

| 2 | Low self-esteem, which consists in having a tendentially negative attitude towards life, believing little in oneself or in one’s own resources, or in any case in one’s abilities and means, due to insecurity, with a tendency to isolation, loneliness, a sedentary lifestyle, poor self-care or self-abandonment with/without a decrease in social and affective relationships (affective symptoms) |  |  |  | ||

| 3 | Marked decrease in pleasure in carrying out new interests and activities (anhedonia) or in any case previously liked or interested, while now they arouse fatigue, apathy, fear of failure, boredom and disinterest |  |  |  | ||

| 4 | Significant increase or decrease in body weight since the onset of the first depressive symptoms, which may result in eating disorders |  |  |  | ||

| 5 | Psychomotor agitation or slowdown, in the absence of manic/hypomanic symptoms and/or marked neurotic symptoms (e.g., phobic, obsessive, somatic), with/without alterations in the sleep–wake rhythm (insomnia or hypersomnia) and in one’s natural biorhythm |  |  |  | ||

| 6 | Perception of lack of energy or easy fatigue (asthenia) |  |  |  | ||

| 7 | Feelings of self-devaluation, restlessness, helplessness, worthlessness, inadequacy, emptiness, guilt, or shame, affecting self-perception and ability to plan |  |  |  | ||

| 8 | Reduced ability to concentrate and/or memory |  |  |  | ||

| 9 | Recurrent negative, melancholic or death-related thoughts that are not provoked by real events (e.g., mourning) |  |  |  | ||

| __/9(Y) |  | ||||

| SECTION C: Thematic path for differential diagnosis | ||||||

| N | Item | Answer | ||||

| 1 | Is there a perceived dysfunctional mental state, with depressive symptoms? (If the answer is “no” you can interrupt the questionnaire, with the result of “Absence of clinically relevant depressive state” and you can stop the administration, if the answer is “yes” you can continue with no. 2) |  | ||||

| 2 | Is the score in the third column of Section B of the questionnaire at least 5/9? (If the answer is “no” you can continue with no. 3, if the answer is “yes” you must continue with no. 8) |  | ||||

| 3 | Has the respondent recently been exposed to one or more sources of stress to which he or she cannot resolutely adapt, and has he or she developed an abnormal and/or distressing emotional and behavioral response? (If the answer is “no” you can continue with no. 5, if the answer is “yes” you must continue with no. 4) |  | ||||

| 4 | Is the period of difficulty or inability to adapt decisively, to the specific source of stress, lasting less than 30 days? (If the answer is “no” you can continue with no. 5, if the answer is “yes” the diagnosis will be “Adjustment disorder, with depressive symptoms” and you can stop the administration) |  | ||||

| 5 | Is the stressful event to which one cannot adapt decisively perceived by the interviewee as a traumatic event? (If the answer is “no” you can continue with no. 7, if the answer is “yes” you must continue with no. 6) |  | ||||

| 6 | Is the traumatic event capable of generating intrusive thoughts, nightmares, flashbacks, avoidance of trauma memories, negative cognitions and mood, hypervigilance, and sleep disturbances? (If the answer is “no” you can continue with no. 7, if the answer is “yes”, to at least 50% of the requirements listed, the diagnosis is “Post-traumatic stress disorder, with depressive symptoms” and the administration can be stopped, if the answer is “yes” but with less than 50% of the requirements listed, the administration can be continued with no. 7) |  | ||||

| 7 | Does the interviewee manifest, in addition to depressive symptoms, specific neurotic symptoms of an anxious type (panic, phobias, avoidance, obsessions, somatizations) capable of negatively impacting daily life in a significant way? (If the answer is “no” you can continue with no. 8, if the answer is “yes” the diagnosis is “Specific anxiety disorder, with depressive symptoms” and the administration can be stopped) |  | ||||

| 8 | Does the depressive state last less than 30 days? (If the answer is “no” you can continue with no. 12, if the answer is “yes” you can continue with no. 9) |  | ||||

| 9 | Is the depressive state connected to one’s premenstrual/menstrual period? (If the answer is “no” you can continue with no. 10, if the answer is “yes” the diagnosis is “Premenstrual/menstrual dysphoric disorder and the administration can be discontinued) |  | ||||

| 10 | Is the depressive state connected to seasonality or in any case to the weather/? (If the answer is “no” you can continue with no. 11, if the answer is “yes” the diagnosis is “Seasonal dysphoric or meteopathic disorder and the administration can be stopped) |  | ||||

| 11 | Is the depressive state connected to the stressful-traumatic event, despite psychotherapeutic intervention? (If the answer is “no” you can continue with no. 12, if the answer is “yes” the diagnosis is “Complicated adjustment disorder and the administration can be stopped) |  | ||||

| 12 | Is the depressive state only partially able to compromise general mental functioning, with marked perceptions of discomfort and psychophysical malaise, without however preventing him from living his own existence and without excessive impairments (in any case less than 50% of the average quality of life) in the spheres of life? (If the answer is “no” you can continue with no. 13, if the answer is “yes” the diagnosis is “Sub-clinical depressive disorder can be discontinued) |  | ||||

| 13 | Has the depressive state lasted for more than 90 days? (If the answer is “no” the diagnosis is “Atypical depressive disorder and the administration can be stopped, if the answer is “yes” the answer can be continued with no. 14) |  | ||||

| 14 | Is the depressive state present continuously or in any case for more than 75% of the average time of the reference period? (If the answer is “no” the diagnosis is “Atypical depressive disorder and the administration can be stopped, if the answer is “yes” the answer can be continued with no. 15) |  | ||||

| 15 | Has the depressive state lasted for at least 1 year? (If the answer is “no” the diagnosis is “Atypical depressive disorder and the administration can be stopped, if the answer is “yes” the answer can be continued with no. 16) |  | ||||

| 16 | Is the depressive state present continuously or in any case for more than 75% of the average time of the reference period? (If the answer is “no” the diagnosis is “Reactive depressive disorder and the administration can be stopped, if the answer is “yes” the answer can be continued with no. 17) |  | ||||

| 17 | Has the depressive state lasted for at least 2 years? (If the answer is “no” the diagnosis is “Dysthymic depressive disorder and the administration can be stopped, if the answer is “yes” the answer can be continued with no. 18) |  | ||||

| 18 | During the depressive state, are there anxious-humoral symptoms (e.g., panic, phobias, obsessions, avoidance, somatization, hypomanic), dramatic (e.g., manic, grandiose, theatrical, impulsiveness, antisociality, psychopathy) and/or psychotic (e.g., delusions, hallucinations, dissociations, paranoia), in a non-sporadic, non-occasional and disabling way? (If the answer is “no” the diagnosis is “Major depressive disorder” and the administration can be stopped, if the answer is “yes” the diagnosis is “Mixed form depressive disorder” of the anxious-depressive, manic-depressive-dramatic-depressive or psychotic-depressive type, based on the specific symptoms”, and the administration can be stopped) |  | ||||

| CLINICAL NOTES | ||||||

References

- Perrotta, G. Depressive disorders: Definitions, contexts, differential diagnosis, neural correlates and clinical strategies. Arch. Depress. Anxiety 2019, 5, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Pub.: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel-Ramsay, J.E.; Bertocci, M.A.; Wu, B.; Phillips, M.L.; Strakowski, S.M.; Almeida, J.R.C. Distinguishing between depression in bipolar disorder and unipolar depression using magnetic resonance imaging: A systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 2022, 24, 474–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vita, A.; Rossi, A.; Amore, M.; Carpiniello, B.; Fagiolini, A.; Maina, G. Manuale di Psichiatria; Edra: Palm Beach Gardens, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta, G. “Perrotta Integrative Clinical Interviews-3” (PICI-3): Development, regulation, updation, and validation of the psychometric instrument for the identification of functional and dysfunctional personality traits and diagnosis of psychopathological disorders, for children (8–10 years), preadolescents (11–13 years), adolescents (14–18 years), adults (19–69 years), and elders (70–90 years). Ibrain 2024, 10, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingiardi, V.; McWilliams, N. Manuale Diagnostico Psicodinamico (PDM), 2nd ed.; Raffaello Cortina: Milan, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey, S.; Ng, E.D.; Wong, C.H.J. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 61, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Pabst, A.; Luppa, M. Risk factors and protective factors of depression in older people 65+. A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smythe, K.L.; Petersen, I.; Schartau, P. Prevalence of Perinatal Depression and Anxiety in Both Parents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2218969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarron, R.M.; Shapiro, B.; Rawles, J.; Luo, J. Depression. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, ITC65–ITC80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.M.; Adams, M.J.; Clarke, T.-K.; Hafferty, J.D.; Gibson, J.; Shirali, M.; Coleman, J.R.I.; Hagenaars, S.P.; Ward, J.; Wigmore, E.M.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.F.; Neale, M.C.; Kendler, K.S. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, S.M.; Harkness, K.L. Major Depression and Its Recurrences: Life Course Matters. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 18, 329–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutt, D.J. Relationship of neurotransmitters to the symptoms of major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69 (Suppl. E1), 4–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DeFilippis, M.; Wagner, K.D. Management of treatment-resistant depression in children and adolescents. Paediatr. Drugs 2014, 16, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joca, S.R.; Moreira, F.A.; Wegener, G. Atypical Neurotransmitters and the Neurobiology of Depression. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2015, 14, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troubat, R.; Barone, P.; Leman, S.; Desmidt, T.; Cressant, A.; Atanasova, B.; Brizard, B.; El Hage, W.; Surget, A.; Belzung, C.; et al. Neuroinflammation and depression: A review. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 53, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leistner, C.; Menke, A. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and stress. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2020, 175, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarno, E.; Moeser, A.J.; Robison, A.J. Neuroimmunology of depression. Adv. Pharmacol. 2021, 91, 259–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, I.C.K.; Bernardes, J.W.; Monteiro, J.K.; Marin, A.H. Stress, anxiety and depression among gastronomes: Association with workplace mobbing and work-family interaction. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2021, 94, 1797–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.J.; Schmidt, C.; Abraham, A.; Walker, L.; Tercyak, K. Adolescents' social environment and depression: Social networks, extracurricular activity, and family relationship influences. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2009, 16, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalin, N.H. Anxiety, Depression, and Suicide in Youth. Am. J. Psychiatry 2021, 178, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, D.; Marshall, K. Depression and Loss in Older Adults. Home Healthc. Now. 2019, 37, 353–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassarini, J. Depression in midlife women. Maturitas 2016, 94, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faravelli, C. Psicofarmacologia per Psicologi; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rodziewicz, T.L.; Houseman, B.; Vaqar, S.; Hipskind, J.E. Medical Error Reduction and Prevention. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ormel, J.; Hollon, S.D.; Kessler, R.C.; Cuijpers, P.; Monroe, S.M. More treatment but no less depression: The treatment-prevalence paradox. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 91, 102111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devita, M.; De Salvo, R.; Ravelli, A.; De Rui, M.; Coin, A.; Sergi, G.; Mapelli, D. Recognizing Depression in the Elderly: Practical Guidance and Challenges for Clinical Management. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2022, 7, 2867–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S.; Niu, Z.; Lyn, D.; Cui, L.; Wu, X.; Yang, L.; Qiu, H.; Gu, W.; Fang, Y. Analysis of Seasonal Clinical Characteristics in Patients With Bipolar or Unipolar Depression. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 847485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Chen, S.; Ke, Y.; Qi, S.; Wei, X.; Ming, D. Discriminating subclinical depression from major depression using multi-scale brain functional features: A radiomics analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, N.R.; Blanke, J.; Leenings, R.; Ernsting, J.; Fisch, L.; Sarink, K.; Barkhau, C.; Emden, D.; Thiel, K.; Flinkenflügel, K.; et al. A Systematic Evaluation of Machine Learning-Based Biomarkers for Major Depressive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, J.F. Diagnosis and Pharmacotherapy of Bipolar Depression in Adults. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2021, 82, SU120014BR1C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfeld, R.M. Differential diagnosis of bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 169 (Suppl. S1), S12–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G. Pseudo-melancholia. Australas. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, P.B.; Gilliam, W.S. Differential diagnosis of childhood depression: Using comorbidity and symptom overlap to generate multiple hypotheses. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 1994, 24, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernberg, O.F.; Yeomans, F.E. Borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder: Practical differential diagnosis. Bull. Menn. Clin. 2013, 77, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishore, K.; Jaswal, V.; Kulkarni, V.; De, D. Practical Guidelines to Develop and Evaluate a Questionnaire. Indian. Dermatol. Online J. 2021, 12, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrotta, G.; Basiletti, V.; Eleuteri, S. The “Human Emotions” and the new “Perrotta Human Emotions Model” (PHEM-2): Structural and functional updates to the first model. Open J. Trauma. 2023, 7, 022–034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. The reality plan and the subjective construction of one’s perception: The strategic theoretical model among sensations, perceptions, defence mechanisms, needs, personal constructs, beliefs system, social influences and systematic errors. J. Clin. Res. Rep. 2019, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).