The Benefits of Hypnosis Support in Stress Management for First-Year Students at the Higher Institute of Nursing and Health Techniques, Rabat

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Target Population and Participant Allocation

- An intervention group, which received hypnosis sessions delivered over 10 weeks;

- A control group, which received no specific intervention.

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Measurement Scales

- T0 (baseline = pre-intervention);

- T1 (post-intervention).

- The Visual Analog Scale for Stress (VAS), a 10 cm horizontal line representing stress intensity from “no stress” to “maximum imaginable stress”. The students marked the point that best reflected their stress level, and the distance from the zero point was used as a quantitative score.

- The 14-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) was developed by Cohen et al. and has been translated and validated in French [20] and Arabic [21]. The PSS-14 assesses perceived stress over the past month using 14 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “Never” to 4 = “Very often”). Total scores < 18 indicate low stress, whereas scores > 38 indicate high stress. In this study, internal consistency was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = 0.76).

2.5. Structure of the Hypnosis Sessions

- The first session is devoted to introducing hypnosis, outlining its key characteristics, the typical stages of a session, and the concept of hypnotic trance. It begins with a preliminary discussion designed to explore the participants’ expectations, attitudes, and prior experiences, as well as to identify their perceptions and detect any potential contraindications to hypnosis. This initial exchange is followed by the establishment of a therapeutic alliance, fostering trust and collaboration between the practitioner and the participant. The session concludes with a cardiac coherence exercise, offering the participants an initial experience of relaxation and promoting a sense of connection and self-regulation.

- Second, Third, Fourth, and Fifth Session During the second, third, fourth, and fifth sessions, the standard stages of a hypnosis session were systematically followed, including induction, suggestions, awakening, and debriefing.

- ✓

- Induction: Each session begins by welcoming the students and ensuring they are physically and psychologically comfortable. Contextually adapted hypnotic induction is then conducted to facilitate a state of relaxation and focused attention. This induction incorporates the free exploration of visual sensations, specifically designed to stimulate creativity and prime the mind to receive therapeutic suggestions effectively.

- ✓

- Suggestions: Students are guided to recall a past experience associated with personal success, with the aim of eliciting positive emotions and physiological responses. This reflective process serves as an anchor to reinforce self-esteem and enable participants to draw upon their internal resources. Subsequently, a structured mental projection exercise encourages them to anticipate potentially stressful future situations—such as examinations or academic challenges—while simultaneously mobilizing these internal resources to regulate negative emotions and foster a sense of preparedness and confidence.Through the use of evocative metaphors such as the “balloon” technique, students learn to gradually release emotional tension and envision positive mental transformations. This process concludes with the reframing of an imagined ideal into a realistic and achievable goal, supported by suggestions that reinforce their abilities and promote constructive, success-oriented thinking.

- ✓

- Awakening: The return to wakefulness is gradual and structured. It relies on multisensory techniques, engaging the five senses, auditory (hearing), visual (imagery), kinesthetic (touch and movement), olfactory (smell), and gustatory (taste), with a particular emphasis on auditory and visual stimuli. A specific physical gesture is introduced to anchor internal resources, enabling students to retain and reactivate the benefits of the session.

- ✓

- Debriefing: The session concludes with a debriefing phase, during which students are invited to share their impressions and reflect on their hypnotic experience. The hypnotherapist supports them in recognizing their capacity to influence their internal states, behaviors, and surrounding environment.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

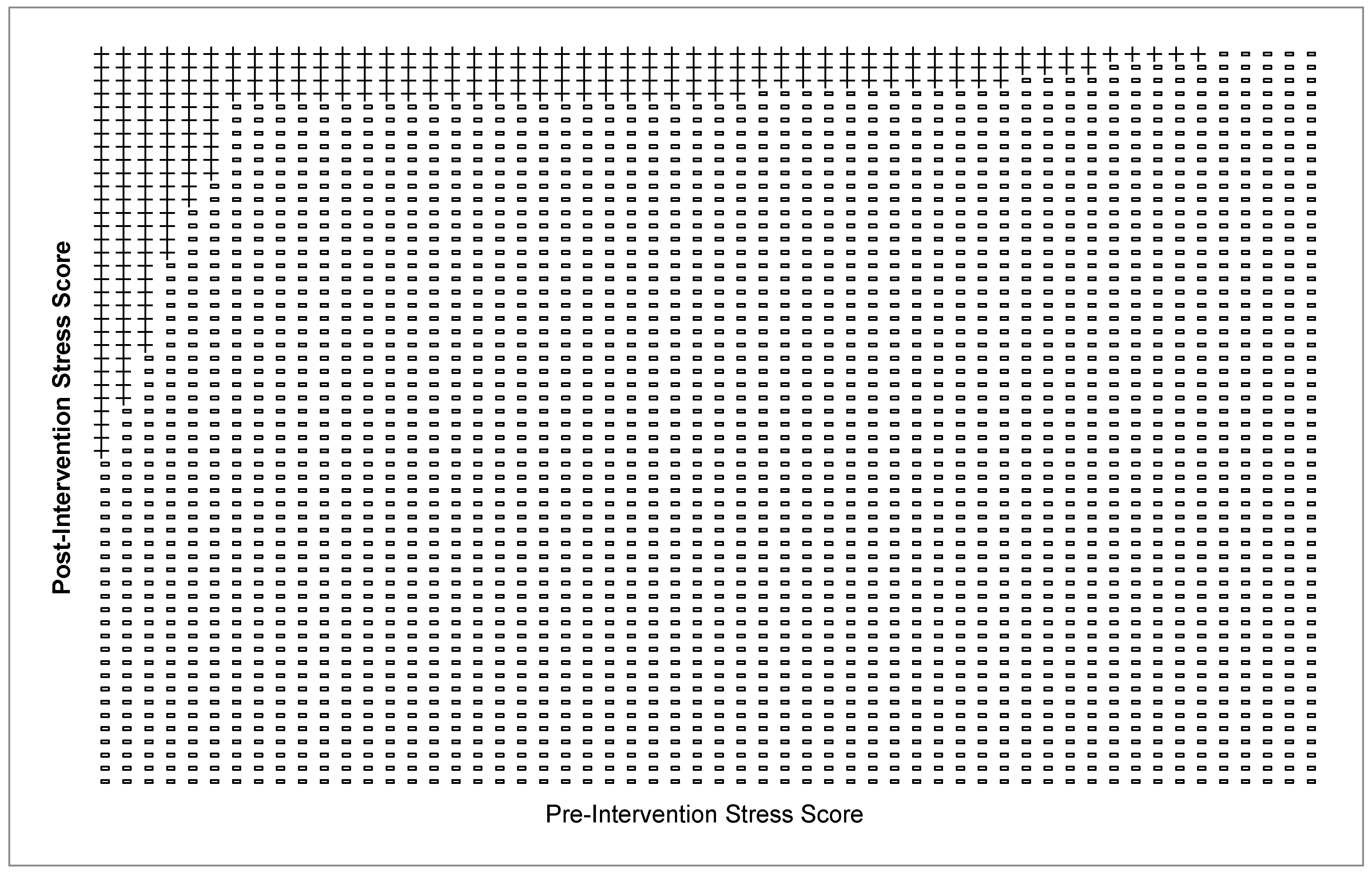

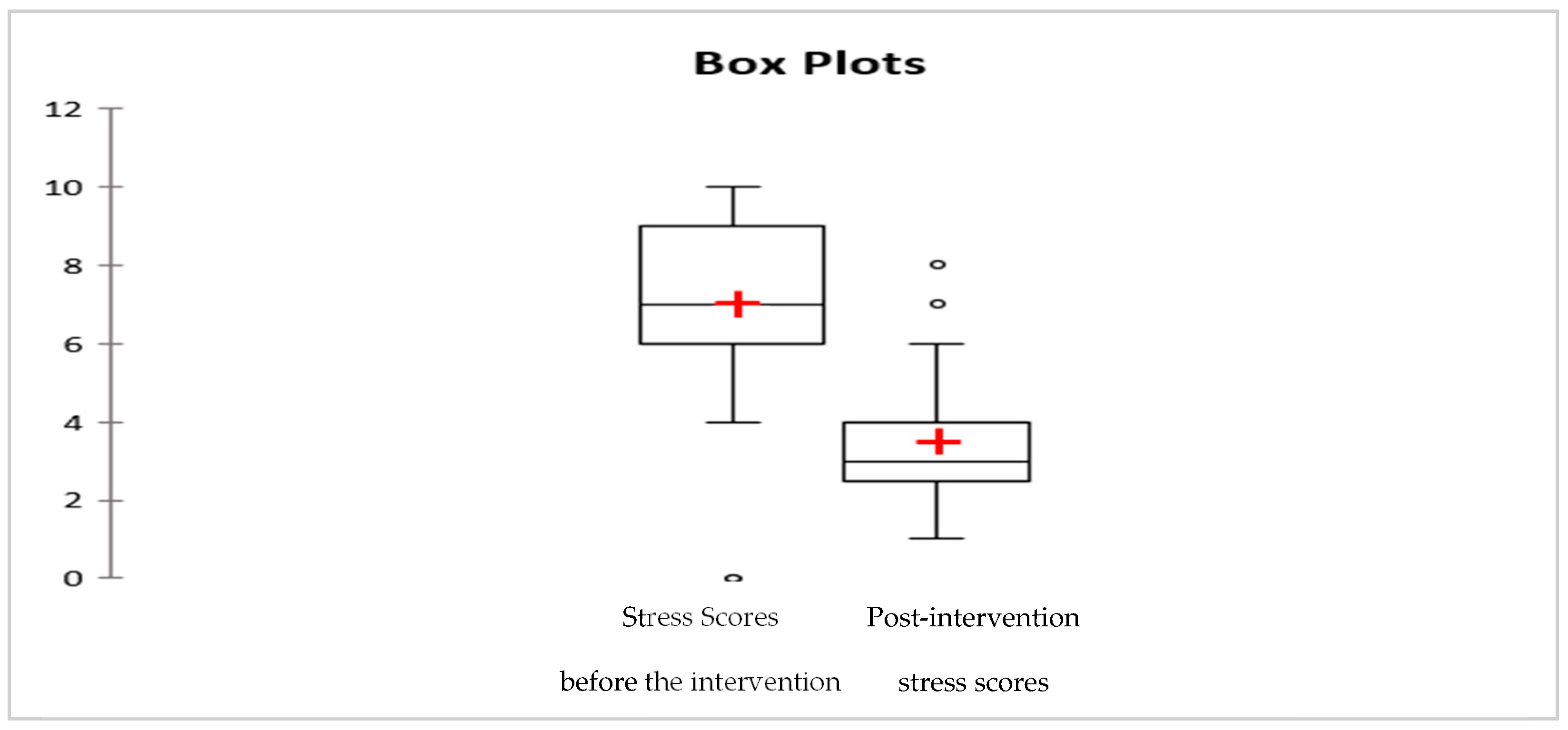

3.1. VAS Score Results (Inter- and Intra-Group)

3.2. Effect of the Hypnosis Intervention on Perceived Stress (PSS-14 Scores and Statistical Analysis)

3.3. Graphical Presentation of Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Clercq, M.; Frenay, M.; Wouters, P.; Raucent, B. Pédagogie Active Dans L’enseignement Supérieur: Description de Pratiques et Repères Théoriques. 2022. Available online: https://dial.uclouvain.be/pr/boreal/object/boreal:265191 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Garnham, W.; Gowers, I. Active Learning in Higher Education: Theoretical Considerations and Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lassarre, D.; Giron, C.; Paty, B. Stress des étudiants et réussite universitaire: Les conditions économiques, pédagogiques et psychologiques du succès1. L’Orientation Sc. Et Prof. 2003, 32/4, 669–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavolacci, M.P.; Ladner, J.; Grigioni, S.; Richard, L.; Villet, H.; Dechelotte, P. Prevalence and association of perceived stress, substance use and behavioral addictions: A cross-sectional study among university students in France, 2009–2011. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbayannis, G.; Bandari, M.; Zheng, X.; Baquerizo, H.; Pecor, K.W.; Ming, X. Academic Stress and Mental Well-Being in College Students: Correlations, Affected Groups, and COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 886344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, F.; Wagner, R.; Kolanisi, U.; Makuapane, L.; Masango, M.; Gómez-Olivé, F. The relationship between depression symptoms and academic performance among first-year undergraduate students at a South African university: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Peng, C.; Chen, C. Mental health and academic performance of college students: Knowledge in the field of mental health, self-control, and learning in college. Acta Psychol. 2024, 248, 104351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzoni, N.; Graz, B.; Bonvin, R.; Dodin, S.; Bonvin, E. Etudiants en médecine et exercices de gestion du bien-être: Étude de faisabilité. Rev. Médicale Suisse 2019, 15, 1193–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Cao, X. Bidirectional reduction effects of perceived stress and general self-efficacy among college students: A cross-lagged study. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, J.S.; Howard, J.L.; Chong, J.X.Y.; Guay, F. Pathways to Student Motivation: A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents of Autonomous and Controlled Motivations. Rev. Educ. Res. 2022, 92, 46–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavagne, C. Évaluation du Bien-être des Etudiants Sages-Femmes au sein du Departement de Maïeutique de Grenoble. Diplome de Sage Femme, Université Grenoble-Alpes UFR de Médecine de Grenoble. 2020. Available online: https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02985804 (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Liu, X.; Zhu, C.; Dong, Z.; Luo, Y. The Relationship between Stress and Academic Self-Efficacy among Students at Elite Colleges: A Longitudinal Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Madani, H.; El Harch, I.; Bahra, N.; Bourkhime, H.; Tachfouti, N.; Fakir, S.E.; Berraho, M. Le stress perçu et le rendement académique chez les étudiants en soins infirmiers au Maroc: Étude transversale. Rev. D’épidémiologie Santé Publique 2023, 71, 101666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don Smith, J. The Psychological Secrets Special Forces Use to Stay Calm Under Fire. Operational & Defense Psychology Review. Available online: https://medium.com/operational-defense-psychology-review/the-psychological-secrets-special-forces-use-to-stay-calm-under-fire-cc12ba393a6a (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Sala, G.; Haag, C. Comment vaincre l’anxiété en situation extrême?: Les secrets du GIGN, unité d’élite de la gendarmerie nationale. Rev. Française De Gest. 2016, 42, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, D.; Camart, N.; Romo, L. Intervention de gestion du stress par Internet chez les étudiants: Revue de la littérature. Ann. Médico-Psychol. Rev. Psychiatr. 2017, 175, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, M.; Adam, S.H.; Fleischmann, R.J.; Baumeister, H.; Auerbach, R.; Bruffaerts, R.; Cuijpers, P.; Kessler, R.C.; Berking, M.; Lehr, D.; et al. Effectiveness of an Internet- and App-Based Intervention for College Students With Elevated Stress: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebhinani, N.; Kuppili, P.P.; Mamta. Feasibility and effectiveness of stress management skill training in medical students. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2024, 80, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, C.; Scholz, M.; Bischofsberger, L.; Hammer, A.; Kleinsasser, B.; Paulsen, F.; Burger, P.H.M. Positive effects of medical hypnosis on test anxiety in first year medical students. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2021, 59, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinghausen, L.; Collange, J.; Botella, M.; Emery, J.-L.; et Albert, É. Validation factorielle de l’échelle française de stress perçu en milieu professionnel. Santé Publique 2009, 21, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubir, D.B.; Serhier, Z.; Otmani, N.; Housbane, S.; Mouddene, N.A.; Agoub, M.; Othmani, M.B. Le stress perçu: Validation de la traduction d’une échelle de mesure de stress en dialecte marocain. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2015, 21, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnier, P.-H.; Hardy Laudrin, B. Cas Pratiques en Hypnose Pour L’éducation Thérapeutique du Patient; Dunod: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Roulet, E. Intérêt à Moyen et Long Terme des Techniques D’autohypnose dans la Prise en Charge des Douleurs Chroniques. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Toulouse III–Paul Sabatier Facultés De Medecine, Toulouse, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, G.; Bonvin, E. (Eds.) Soigner par L’hypnose; Elsevier Masson: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dowd, E.T.; Healy, J.M. (Eds.) Case Studies in Hypnotherapy; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, S.J.; Kirsch, I. Essentials of Clinical Hypnosis: An Evidence-Based Approach; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Voit, R.; DeLaney, M. Hypnosis in Clinical Practice: Steps for Mastering Hypnotherapy; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M.E.; Wright, B.A. Clinical Practice of Hypnotherapy; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaz, Z.J.; Baig, M.; Al Alhendi, B.S.M.; Al Suliman, M.M.O.; Al Alhendi, A.S.; Al-Grad, M.S.H.; Qurayshah, M.A.A. Perceived stress, reasons for and sources of stress among medical students at Rabigh Medical College, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagat, V.; Menon, S. A Review Study on Self-hypnosis in the Management of High-Level Anxiety Affecting Educational Performance of University Students. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2019, 12, 1986–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitz, É.; Constantini, M.-L.; Baumann, M. Détresse psychologique et stratégies de coping des étudiants en première année universitaire. Rev. Francoph. Stress Trauma 2007, 7, 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Strenna, L.; Chahraoui, K.; Vinay, A. Santé psychique chez les étudiants de première année d’école supérieur e de commerce: Liens avec le stress de l’orientation professionnelle, l’estime de soi et le coping. L’Orientation Sc. Prof. 2009, 38/2, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.L.; Saunders, K.E.; Keown-Stoneman, C.D.G.; Duffy, A.C. Mental health trajectories in undergraduate students over the first year of university: A longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, L.M.; Jackson, H.M.; Gulliver, A.; Calear, A.L.; Batterham, P.J. Mental Health Among First-Year Students Transitioning to University in Australia: A Longitudinal Study. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 00332941241295978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karing, C.; Oeltjen, L. A longitudinal study of the psychological predictors of mental health and stress among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 35722–35735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, A.; Keown-Stoneman, C.; Goodday, S.; Horrocks, J.; Lowe, M.; King, N.; Pickett, W.; McNevin, S.H.; Cunningham, S.; Rivera, D.; et al. Predictors of mental health and academic outcomes in first-year university students: Identifying prevention and early-intervention targets. BJPsych. Open 2020, 6, e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langevin, V.; Boini, S.; François, M.; Riou, A. Échelle visuelle analogique (ÉVA). Références En Santé Au Trav. 2012, 130, 167–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lesage, F.-X.; Chamoux, A. Utilisation de l’échelle visuelle analogique (EVA) dans l’évaluation du stress au travail: Limites et perspectives. Revue de la littérature. Arch. Des Mal. Prof. L’environnement 2008, 69, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesage, F.-X.; Berjot, S.; Deschamps, F. Clinical stress assessment using a visual analogue scale. Occup. Med. 2012, 62, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worobetz, A.; Retief, P.J.; Loughran, S.; Walsh, J.; Casey, M.; Hayes, P.; Bengoechea, E.G.; O’Regan, A.; Woods, C.; Kelly, D.; et al. A feasibility study of an exercise intervention to educate and promote health and well-being among medical students: The ‘MED-WELL’ programme. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Sample Size (N) | Sample Size of the Control Group | Sample Size of the Intervention Group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Track 1: Environmental Health Technician | 30 | 15 | 15 |

| Track 2: Psychomotor Therapist | 36 | 18 | 18 |

| Track 3: Occupational Therapist | 30 | 15 | 15 |

| Track 4: Dietitians and Nutritionists | 30 | 15 | 15 |

| Track 5: Nurse Anesthetists | 40 | 20 | 20 |

| Total Sample Size (N) | 166 | 83 | 83 |

| University Track | Comparison Group | Timepoint | Mean ± SD | Difference in Means (T0–T1:10) | Mean T0 Intervention–Mean T0 Control | Mean T1:10 Intervention–Mean T1:10 Control | Paired Samples t-Test | p-Value (from Paired Samples t-Test) | Critical Value | IC (95%) | Independent Samples t-Test | p-Value (from Independent Samples t-Test) | Critical Value | IC (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Comparison (All tracks Combined) | Control Group | T0 | 7.63 ± 1.78 | - | 0.25 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.85 | 0.4 | 1.97 | [−0.33; 0.84] |

| Intervention Group | 7.89 ± 2.05 | |||||||||||||

| Track 1: Environmental Health Technician | Control Group | T0 | 8.29 ± 1.38 | 1.88 | - | - | 3.37 | 0.005 | 2.14 | [0.6; 2.73] | −4.93 | 0.0000 *** | 2.05 | [−4.62; −1.91] |

| T1 | 6.41 ± 1.8 | |||||||||||||

| Intervention Group | T0 | 8.27 ± 2.31 | 5.14 | - | - | 7.76 | 0.0000 *** | 2.14 | [3.28; 5.79] | |||||

| T1 | 3.13 ± 1.74 | |||||||||||||

| Track 2: Psychomotricity | Control Group | T0 | 8.06 ± 1.30 | 2.50 | - | - | 7.91 | 0.0000 *** | 2.11 | [1.83; 3.17] | −4.43 | 0.0000 *** | 2.03 | [−3.48; −1.29] |

| T1 | 5.56 ± 1.15 | |||||||||||||

| Intervention Group | T0 | 7.47 ± 2.65 | 4.29 | - | - | 7.69 | 0.0000 *** | 2.11 | [2.94; 5.17] | |||||

| T1 | 3.18 ± 1.98 | |||||||||||||

| Track 3: Occupational Therapy | Control Group | T0 | 7.76 ± 1.74 | 1.76 | - | - | 6.5 | 0.0000 *** | 2.14 | [1.16; 2.30] | −4.88 | 0.0003 *** | 2.04 | [−3.69; −1.51] |

| T1 | 6.00 ± 1.51 | |||||||||||||

| Intervention Group | T0 | 7.47 ± 1.46 | 3.78 | - | - | 8.9 | 0.0000 *** | 2.14 | [2.83; 4.63] | |||||

| T1 | 3.18 ± 1.50 | |||||||||||||

| Track 4: Dietetics and Nutrition | Control Group | T0 | 7.38 ± 2.09 | 1.81 | - | - | 3.36 | 0.005 | 2.14 | [0.65; 2.95] | −2.34 | 0.02 | 2.05 | [−2.3; 0.20] |

| T1 | 5.56 ± 2.00 | |||||||||||||

| Intervention Group | T0 | 7.56 ± 1.70 | 3.78 | - | - | 9.13 | 0.0000 *** | 2.14 | [2.91; 4.69] | |||||

| T1 | 3.78 ± 1.83 | |||||||||||||

| Track 5: Anesthesia | Control Group | T0 | 7.40 ± 2.28 | 1.85 | - | - | 4.61 | 0.0002 *** | 2.09 | [0.85; 2.25] | −3.89 | 0.0004 *** | 2.02 | [−3.42; −1.08] |

| T1 | 5.55 ± 1.98 | |||||||||||||

| Intervention Group | T0 | 9.45 ± 0.86 | 5.50 | - | - | 15.36 | 0.0000 *** | 2.09 | [5.22; 6.87] | |||||

| T1 | 3.95 ± 1.78 | |||||||||||||

| Post-Treatment Comparison (All Tracks Combined) | Control Group | T1 | 5.78 ± 1.72 | - | - | 2.4 | - | - | - | - | −9.06 | 0.0000 *** | 1.97 | [−2.93; −1.88] |

| Intervention Group | 3.37 ± 1.71 |

| Comparison (All Tracks Combined) | Comparison Group | Timepoint | PSS-14 Mean ± SD | Stress Category | Mean Difference ± SD | t | Critical Value | p-Value | IC (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison (All tracks Combined) | Control Group | T0 | 26.13 ± 6.86 | Moderate stress | 0.33 ± 6.50 | 0.45 | 2.0 | 0.65 | −0.95–1.61 |

| T1 | 25.80 ± 5.50 | Moderate stress | |||||||

| Intervention Group | T0 | 26.42 ± 7.54 | Moderate stress | 2.09 ± 7.70 | 2.21 | 2.0 | 0.030746 | 0.2–3.98 | |

| T1 | 24.32 ± 8.20 | Moderate stress |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benarfa, I.; Oudghiri, D.E.; Mountaj, N.; El Hessni, A.; Mesfioui, A.; Ahyayauch, H. The Benefits of Hypnosis Support in Stress Management for First-Year Students at the Higher Institute of Nursing and Health Techniques, Rabat. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030103

Benarfa I, Oudghiri DE, Mountaj N, El Hessni A, Mesfioui A, Ahyayauch H. The Benefits of Hypnosis Support in Stress Management for First-Year Students at the Higher Institute of Nursing and Health Techniques, Rabat. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(3):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030103

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenarfa, Ilham, Dia Eddine Oudghiri, Nadia Mountaj, Aboubaker El Hessni, Abdelhalim Mesfioui, and Hasna Ahyayauch. 2025. "The Benefits of Hypnosis Support in Stress Management for First-Year Students at the Higher Institute of Nursing and Health Techniques, Rabat" Psychiatry International 6, no. 3: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030103

APA StyleBenarfa, I., Oudghiri, D. E., Mountaj, N., El Hessni, A., Mesfioui, A., & Ahyayauch, H. (2025). The Benefits of Hypnosis Support in Stress Management for First-Year Students at the Higher Institute of Nursing and Health Techniques, Rabat. Psychiatry International, 6(3), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030103