Vicarious Trauma and Burnout Among Mental Health Professionals in Greece: The Role of Core Self-Evaluations, Self-Compassion, and Occupational Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Burnout of Mental Health Professionals

1.2. Vicarious Trauma and Burnout of Mental Health Professionals

1.3. Protective Factors Against Vicarious Trauma and Burnout of Mental Health Professionals

1.4. The Purpose of the Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Personal and Work-Related Demographics

2.2.2. Core Self-Evaluations

2.2.3. Self-Compassion

2.2.4. Vicarious Trauma

2.2.5. Mental Health Professionals’ Burnout

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Correlations Between Positive Self-Image, Self-Compassion, Vicarious Trauma, Job-Related Variables, and Burn-Out of Mental Health Professionals

3.3. Core Self-Evaluations, Self-Compassion, Vicarious Trauma, and Number of Sessions per Week Explained the Levels of Mental Health Professionals’ Burnout

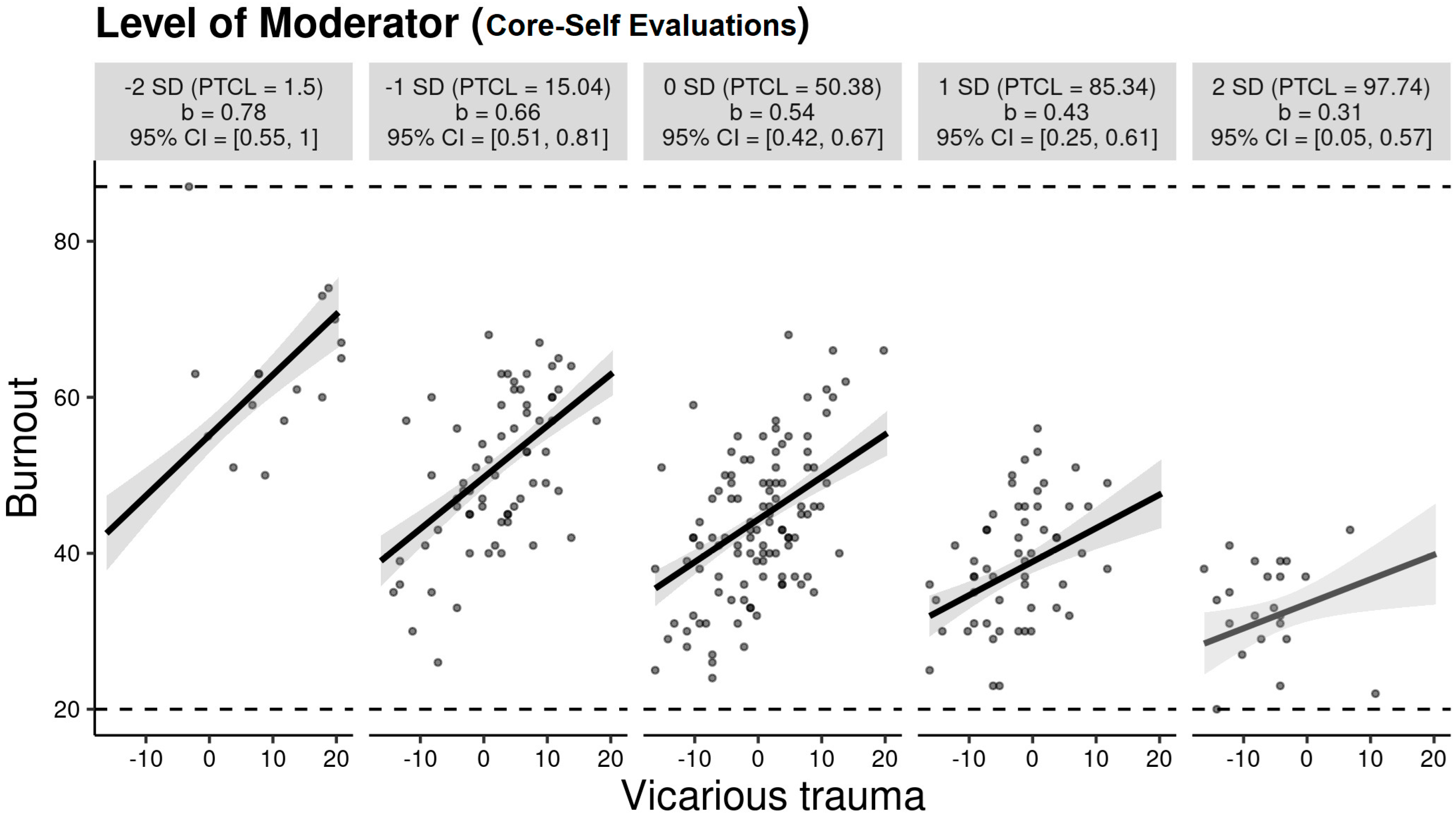

3.4. Core Self-Evaluations Moderated the Relationship Between Vicarious Trauma and Burnout Among Mental Health Professionals

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Studies

4.2. Contributions of the Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acker, G.M. Burnout among mental health care providers. J. Soc. Work 2012, 12, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Burn-Out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. 28 May 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Van Hoy, A.; Rzeszutek, M. Burnout and psychological wellbeing among psychotherapists: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 928191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, K.; Neff, D.M.; Pitman, S. Burnout in mental health professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and determinants. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 53, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory: Third edition. In Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources; Zalaquett, C.P., Wood, R.J., Eds.; Scarecrow Education: Blue Ridge Summit, PA, USA, 1997; pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lakioti, A.; Stalikas, A.; Pezirkianidis, C. The role of personal, professional, and psychological factors in therapists’ resilience. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2020, 51, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreison, K.C.; Luther, L.; Bonfils, K.A.; Sliter, M.T.; McGrew, J.H.; Salyers, M.P. Job burnout in mental health providers: A meta-analysis of 35 years of intervention research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Erwin, P.J.; Shanafelt, T.D. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016, 388, 2272–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupert, P.A.; Morgan, D.J. Work setting and burnout among professional psychologists. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2005, 36, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, L.; Rowe, S.; Hammerton, G.; Billings, J. The contribution of organisational factors to vicarious trauma in mental health professionals: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2022, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, J.M.; MacNeil, G.A. Professional burnout, vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue: A review of theoretical terms, risk factors, and preventive methods for clinicians and researchers. Best Pract. Ment. Health 2010, 6, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslak, R.; Shoji, K.; Douglas, A.; Melville, E.; Luszczynska, A.; Benight, C.C. A meta-analysis of the relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress among workers with indirect exposure to trauma. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, R.R.; Andersen, S.; Song, H.; Townsend, C. Vicarious trauma in mental health care providers. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2021, 24, 100451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trippany, R.L.; Kress, V.E.W.; Wilcoxon, S.A. Preventing vicarious trauma: What counselors should know when working with trauma survivors. J. Couns. Dev. 2004, 82, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.L.; Westwood, M.J. Preventing vicarious traumatization of mental health therapists: Identifying protective practices. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 2009, 46, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branson, D.C. Vicarious trauma, themes in research, and terminology: A review of literature. Traumatology 2019, 25, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, K.P.; Carlson, M.W.; Hatton-Bowers, H.; Fessinger, M.B.; Cole-Mossman, J.; Bahm, J.; Hauptman, K.; Brank, E.M.; Gilkerson, L. Evaluating the facilitating attuned interactions (FAN) approach: Vicarious trauma, professional burnout, and reflective practice. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 112, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounenou, K.; Kalamatianos, A.; Nikoltsiou, P.; Kourmousi, N. The interplay among empathy, vicarious trauma, and burnout in Greek mental health practitioners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bride, B.E.; Radey, M.; Figley, C.R. Measuring compassion fatigue. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2007, 35, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C. Indirect trauma: Implications for self-care, supervision, the organization, and the academic institution. Clin. Superv. 2013, 32, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.E. The power of being positive: The relation between positive self-concept and job performance. Hum. Perform. 1998, 11, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Locke, E.A.; Durham, C.C.; Kluger, A.N. Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, T.A.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.E.; Thoresen, C.J. The Core Self-Evaluations Scale: Development of a measure. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 56, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.S.; Lee, S.; Lu, K.Y. Core self-evaluation and burnout among mental health professionals. J. Couns. Psychol. 2014, 61, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Wong, C.A.; Grau, A.L. Authentic leadership, empowerment and burnout: A comparison in new graduates and experienced nurses. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2003, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, E.; Durkin, M.; Hollins Martin, C.J.; Carson, J. Compassion for others, self-compassion, quality of life, and mental well-being measures in student psychotherapists and student counselors. J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 63, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crego, A.; Yela, J.R.; Riesco-Matías, P.; Gómez-Martínez, M.Á.; Vicente-Arruebarrena, A. The benefits of self-compassion in mental health professionals: A systematic review of empirical research. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 2599–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupert, P.A.; Miller, A.O.; Dorociak, K.E. Preventing burnout: What does the research tell us? Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2015, 46, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaousis, I.; Nikolaou, I.; Serdaris, N.; Judge, T.A. Do the core self-evaluations moderate the relationship between subjective well-being and physical and psychological health? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasidou, E.; Pezirkianidis, C.; Galanakis, M.; Stalikas, A. Validity, reliability and factorial structure of the Self Compassion Scale in the Greek population. J. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 7, 2161–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; Whittaker, T.A.; Karl, A. Examining the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale in four distinct populations: Is the use of a total scale score justified? J. Personal. Assess. 2017, 99, 596–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrklevski, L.P.; Franklin, J. Vicarious trauma: The impact on solicitors of exposure to traumatic material. Traumatology 2008, 14, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Fernández, F.J.; Méndez-Fernández, A.B.; Lombardero-Posada, X.M.; Murcia-Álvarez, E.; González-Fernández, A. Vicarious Trauma Scale: Psychometric properties in a sample of social workers from Spain. Health Soc. Work 2022, 47, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounenou, K.; Gkemisi, S.; Nanopoulos, P.; Tsitsas, G. The psychometric properties of the Counselor Burnout Inventory in Greek school counsellors. J. Psychol. Couns. Sch. 2018, 28, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Baker, C.R.; Cho, S.H.; Heckathorn, D.E.; Holland, M.W.; Newgent, R.A.; Ogle, N.T.; Powell, M.L.; Quinn, J.J.; Wallace, S.L.; et al. Development and initial psychometrics of the Counselor Burnout Inventory. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2007, 40, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, P.; McMurray, I.; Brownlow, C. SPSS Explained; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Matthes, J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 924–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsiopoulos, A.T.; Buchanan, M.J. The practice of self-compassion in counseling: A narrative inquiry. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2011, 42, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Lizarondo, L.; Kumar, S.; Snowdon, D. Impact of clinical supervision on healthcare organisational outcomes: A mixed methods systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionato, G.K.; Simpson, S. Personal risk factors associated with burnout among psychotherapists: A systematic review of the literature. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 1431–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, U.; Luciano, M.; Palumbo, C.; Sampogna, G.; Del Vecchio, V.; Fiorillo, A. Risk of burnout among early career mental health professionals. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouanna, J. Hippocrates (M.B. DeBevoise, Trans.). 1999. Available online: https://archive.org/details/hippocrates0000joua (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Kraut, R. Aristotle on the Human Good; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, R.K. The Handbook of Jungian Psychology: Theory, Practice and Applications; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Georgas, J.; Berry, J.W.; Van de Vijver, F.J.; Kagitçibasi, Ç.; Poortinga, Y.H. (Eds.) Families Across Cultures: A 30-Nation Psychological Study; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. The Therapy of Desire: Theory and Practice in Hellenistic Ethics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, S.; Jenkins, S.R. Vicarious traumatization, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout in sexual assault and domestic violence agency staff. Violence Vict. 2003, 18, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Core self-evaluations | 40.64 (5.93) |

| Self-compassion | 86.00 (16.24) |

| Vicarious trauma | 29.23 (7.94) |

| Burnout | 44.71 (11.29) |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Core self-evaluations | - | ||||||||

| 2. Self-compassion | 0.71 *** | - | |||||||

| 3. Vicarious trauma | −0.39 *** | −0.36 *** | - | ||||||

| 4. Burnout | −0.61 *** | −0.57 *** | 0.59 *** | - | |||||

| 5. Years of personal therapy | 0.12 | 0.10 | −0.05 | −0.09 | - | ||||

| 6. Years of supervision | 0.21 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.07 | −0.19 ** | 0.60 *** | - | |||

| 7. Years of clinical training | 0.21 ** | 0.17 * | −0.04 | −0.17 * | 0.40 *** | 0.36 *** | - | ||

| 8. Years of clinical experience | 0.26 *** | 0.21 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.14 * | 0.39 *** | 0.65 *** | 0.30 *** | - | |

| 9. No of sessions per week | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.13 * | 0.08 | 0.23 *** | 0.20 ** | 0.20 ** | - |

| Predictors | b | SE b | Β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Burnout) | 69.80 | 5.81 | <0.001 | |

| Core self-evaluations | −0.74 | 0.15 | −0.37 | <0.001 |

| Vicarious trauma | 0.51 | 0.08 | 0.34 | <0.001 |

| Self-compassion | −0.16 | 0.05 | −0.23 | 0.002 |

| Number of sessions per week | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.003 |

| Predictors | B | SE B | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Burnout) | 44.33 [43.26, 45.39] | 0.54 | 82.214 | <0.001 |

| Vicarious trauma | 0.54 [0.40, 0.69] | 0.07 | 7.288 | <0.001 |

| Core self-evaluations | −0.91 [−1.14, −0.69] | 0.11 | −7.945 | <0.001 |

| Vicarious trauma × core self-evaluations | −0.02 [−0.04, −0.00] | 0.01 | −2.240 | 0.026 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kounenou, K.; Pezirkianidis, C.; Blantemi, M.; Kalamatianos, A.; Kourmousi, N.; Kostara, S.G. Vicarious Trauma and Burnout Among Mental Health Professionals in Greece: The Role of Core Self-Evaluations, Self-Compassion, and Occupational Factors. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030100

Kounenou K, Pezirkianidis C, Blantemi M, Kalamatianos A, Kourmousi N, Kostara SG. Vicarious Trauma and Burnout Among Mental Health Professionals in Greece: The Role of Core Self-Evaluations, Self-Compassion, and Occupational Factors. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(3):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030100

Chicago/Turabian StyleKounenou, Kalliope, Christos Pezirkianidis, Maria Blantemi, Antonios Kalamatianos, Ntina Kourmousi, and Spyridoula G. Kostara. 2025. "Vicarious Trauma and Burnout Among Mental Health Professionals in Greece: The Role of Core Self-Evaluations, Self-Compassion, and Occupational Factors" Psychiatry International 6, no. 3: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030100

APA StyleKounenou, K., Pezirkianidis, C., Blantemi, M., Kalamatianos, A., Kourmousi, N., & Kostara, S. G. (2025). Vicarious Trauma and Burnout Among Mental Health Professionals in Greece: The Role of Core Self-Evaluations, Self-Compassion, and Occupational Factors. Psychiatry International, 6(3), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030100