Understanding Binge-Watching: The Role of Dark Triad Traits, Sociodemographic Factors, and Series Preferences

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

Variables Associated with Binge-Watching

1.2. Binge-Watching and Dark Triad

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Selection and Recruitment

2.5. Data Collection

2.5.1. Procedures

2.5.2. Instruments

The Sociodemographic Questionnaire

The Questionnaire About Television Series Preferences

The Binge-Watching Engagement and Symptoms Questionnaire (BWESQ)

The Dark Triad Dirty Dozen

2.6. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

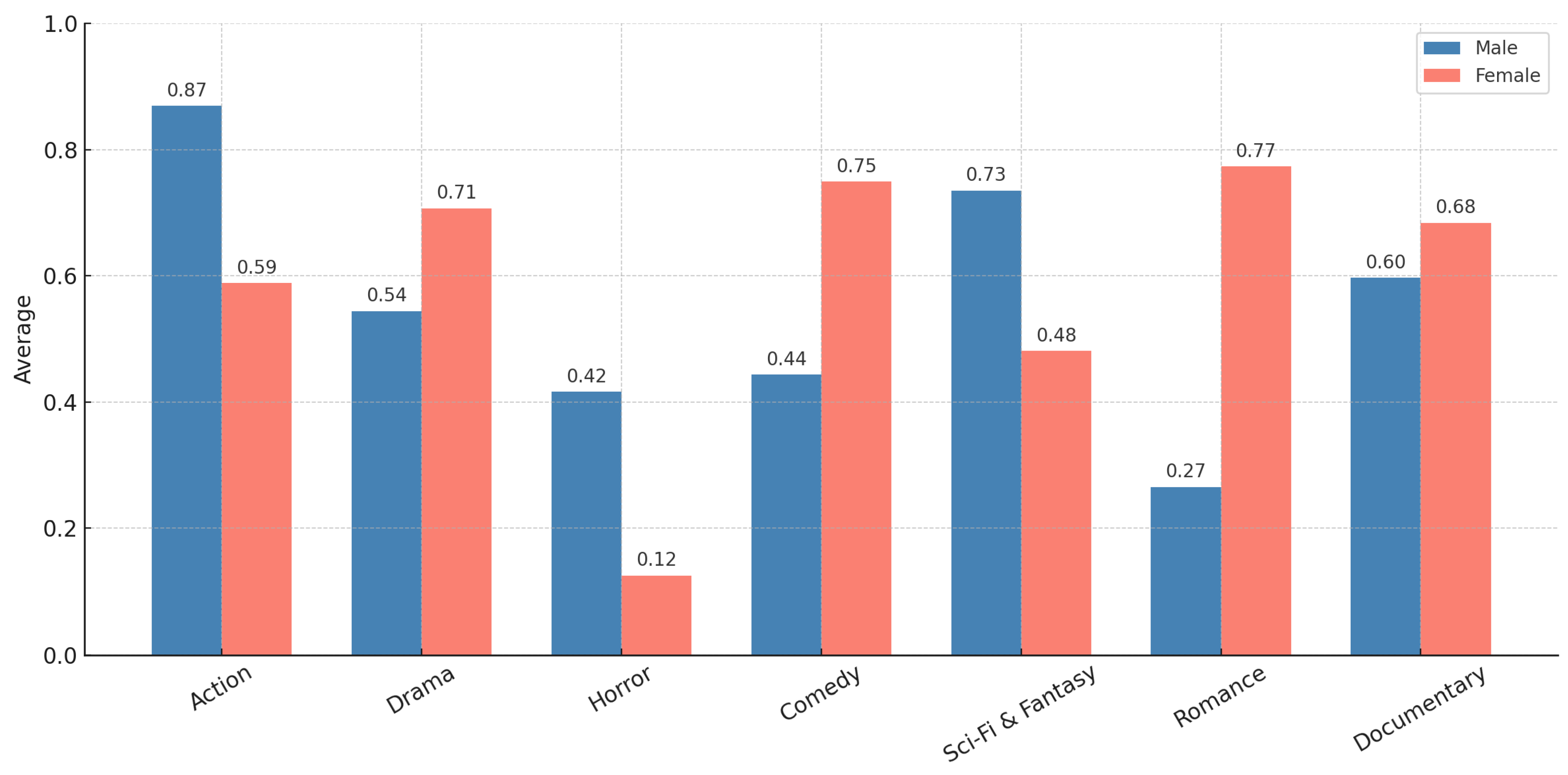

3.2. Descriptives

3.3. Structural Analysis and Measurement Invariance Across Gender

3.4. Descriptives, Reliability, and Convergent and Discriminant Validity of BWESQ

3.5. Descriptives, Reliability, and Convergent and Discriminant Validity of DDT

3.6. Correlations, Skewness, Kurtosis, Tolerance, and Variance Inflation Factor of BWESQ and DDT

3.7. Hierarchical Regression Analyses Predicting Different Binge-Watching Dimensions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire in English

- Sociodemographic Questionnaire

- 1.

- Sex: ☐ Male ☐ Female

- 2.

- Age: ________ years

- 3.

- Professional Status:

- 4.

- Marital Status:

- Questions about TV Series Watching

- 1.

- What type of series do you mostly watch?

| Genre | Yes | No |

| Action | ☐ | ☐ |

| Drama | ☐ | ☐ |

| Horror | ☐ | ☐ |

| Comedy | ☐ | ☐ |

| Science Fiction and Fantasy | ☐ | ☐ |

| Romance | ☐ | ☐ |

| Documentary Series | ☐ | ☐ |

- 2.

- Do you prefer series that are:

Appendix B. Binge-Watching Engagement and Symptoms Questionnaire (BWESQ)

Appendix C. The Dark Triad Dirty Dozen (DD) Scale

Appendix D. The Questionnaire in Portuguese

- Questionário Sociodemográfico

- 1. Sexo: Masculino ☐ Feminino ☐

- 2. Idade ________ anos

- 3. Estatuto Profissional:

- Estudante ☐ Trabalhador(a) Ativo(a) ☐ Desempregado(a) ☐ Reformado(a) ☐

- 4. Estado Civil:

- Solteiro(a), sem relação de namoro ☐ Solteiro(a), mas numa relação de namoro ☐ Casado(a) ou União de facto ☐ Divorciado(a)/Separado(a) ☐ Viúvo(a) ☐

- Questões Relativas ao Visionamento de Séries

- 1.

- Que tipo de séries mais vê?

| Sim | Não | |

| Ação | ||

| Drama | ||

| Terror | ||

| Comédia | ||

| Ficção Científica e fantasia | ||

| Romance | ||

| Séries documentais |

- 2.

- Prefere séries:

Appendix E. Binge-Watching Engagement and Symptoms Questionnaire (BWESQ) in Portuguese

| BWESQ Nesta secção irá ser exposto a uma série de declarações. Escolha entre as opções abaixo o quanto concorda ou discorda das afirmações (de 1—Discordo fortemente a 4—Concordo fortemente). | Discordo fortemente | Discordo | Concordo | Concordo fortemente |

| 1. Passo muito tempo a ver séries televisivas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. Fico ansioso/a pelo momento em que poderei ver um novo episódio da minha série televisiva favorita. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. Por vezes, fico tão concentrado/a na série que perco a noção do tempo. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. Acompanho a data de lançamento de novos episódios para poder manter-me atualizado/a e terminar a série televisiva (temporada). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. Por vezes, sinto-me vazio/a ou nostálgico/a quando a minha série televisiva favorita chega ao fim. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. Estou tão envolvido/a nas minhas séries televisivas que fico isolado/a e, por vezes, até recuso um convite para sair. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7. Geralmente, fico muito entusiasmado/a ao ver um episódio da minha série televisiva favorita. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8. Tendo a ver séries televisivas quando estou de bom humor ou a sentir emoções positivas (quando me sinto feliz, eufórico, etc). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9. Passo muito tempo a falar com as pessoas na Internet sobre séries televisivas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. Fico aborrecido/a ou irritado/a quando sou interrompido/a enquanto vejo a minha série televisiva favorita. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11. Vejo mais séries televisivas do que devia. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12. Por vezes, falho na realização das minhas tarefas diárias para poder passar mais tempo a ver séries televisivas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13. Fico muito irritado/a se recebo informações de alguém sobre próximos episódios antes de os ter visto. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 14. Preciso sempre de ver mais episódios para me sentir satisfeito. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 15. Por vezes, tento não passar tanto tempo a ver séries televisivas, mas falho sempre. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 16. Fico tenso/a, irritado/a ou agitado/a quando não consigo ver a minha série televisiva favorita. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 17. Não durmo tanto quanto devia por causa do tempo que passo a ver séries televisivas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 18. Ver séries televisivas é um dos meus passatempos favoritos. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 19. Frequentemente, passo mais tempo a ver séries televisivas do que o planeado. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 20. Não consigo evitar ver séries televisivas a toda a hora. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 21. Fico muito entusiasmado/a quando um novo episódio é lançado. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 22. Quando um episódio chega ao fim, e por querer saber o que acontece a seguir, frequentemente, sinto uma tensão irresistível que me faz avançar para o episódio seguinte. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 23. A minha família expressa a sua desaprovação em relação ao tempo que passo a ver séries televisivas, que eles consideram demasiado. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 24. Tendo a ver séries televisivas quando me sinto em baixo ou quando sinto emoções negativas (quando me sinto aborrecido/a, triste, etc.) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 25. Frequentemente, fico preocupado/a que possa existir um problema técnico (por exemplo, uma falha na Internet) que me impeça de ver séries televisivas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 26. Estou sempre à procura de novas séries televisivas para ver. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 27. A minha família e os meus amigos consideram-me uma mina de ouro de informação sobre séries televisivas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 28. Geralmente, sinto um prazer intenso ao ver um episódio da minha série de televisiva favorita. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 29. Os meus resultados escolares, académicos ou profissionais estão a sofrer com o tempo que passo a ver séries televisivas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 30. Costumo verificar aplicações de séries televisivas (i.e., IMDb, TVShow Time, TV Series, etc.) que mostram as pontuações e datas de lançamento de séries/filmes. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 31. Geralmente, fico de mau humor, triste, deprimido/a ou aborrecido/a quando não consigo ver nenhuma série televisiva e sinto-me melhor quando posso vê-las. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 32. De vez em quando, sinto-me culpado ou arrependido depois de ver alguns episódios. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 33. Ver episódios de séries televisivas desencadeia emoções positivas (entusiasmo, interesse, excitação, inspiração, etc.) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 34. Frequentemente, preciso de ver o episódio seguinte para voltar a sentir emoções positivas e para aliviar a frustração causada pela interrupção no enredo. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 35. Na minha opinião, as séries de televisivas fazem parte da minha vida e contribuem para o meu bem-estar. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 36. Por vezes, escondo à minha família quanto tempo passei a ver séries televisivas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 37. Preocupo-me se recebo informações sobre um episódio antes de o ver. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 38. Ver séries televisivas é uma causa de felicidade e entusiasmo na minha vida. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 39. Tendo a ver séries televisivas até ficar realmente viciado/a. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 40. Tendo a usar algumas estratégias para manter o prazer que sinto ao ver algo o mais intacto possível (por exemplo, tendo a esperar até a série completa sair para começar a ver e para poder ver compulsivamente, tendo a planear quando e como vou ver a série, tendo a tentar não receber informações sobre um episódio antes de o ver ou tendo a esperar até tarde para começar a ver, se necessário). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Appendix F. Escala Dark Triad Dirty Dozen (DD) in Portuguese

| Dirty Dozen Nesta secção irá ser exposto a uma série de declarações. Para cada afirmação, escolha o quão concorda com as mesmas (de 1—Discordo completamente a 5—Concordo completamente). | Discordo completamente | Discordo | Nem concordo nem discordo | Concordo | Concordo completamente |

| 1. Tenho tendência a levar as outras pessoas a fazerem o que eu quero. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2. Já enganei ou menti para obter o que eu queria. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. Já elogiei (engraixei) pessoas para obter o que eu queria. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4. Tenho tendência a usar as outras pessoas em meu benefício pessoal. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5. Tenho tendência a não sentir remorsos ou arrependimento. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6. Tenho tendência a não me preocupar com o que é certo ou errado. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7. Tenho tendência a ser uma pessoa insensível e fria. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8. Tenho tendência a não me importar com as regras e normas sociais. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9. Tenho tendência a querer que as outras pessoas sintam admiração por mim. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10. Tenho tendência a querer que as outras pessoas me prestem atenção. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11. Tenho tendência a querer ter prestígio ou estatuto social alto. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12. Tenho tendência a esperar que os outros me façam favores especiais. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

References

- Schweidel, D.A.; Moe, W.W. Binge-watching and Advertising. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Pandey, S.C. Binge-watching and college students: Motivations and outcomes. Young Consum. 2017, 18, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flayelle, M.; Castro-Calvo, J.; Vögele, C.; Astur, R.; Ballester-Arnal, R.; Challet-Bouju, G.; Brand, M.; Cárdenas, G.; Devos, G.; Elkholy, H.; et al. Towards a cross-cultural assessment of Binge-watching: Psychometric evaluation of the “watching TV series motives” and “Binge-watching engagement and symptoms” questionnaires across nine languages. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 111, 106410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.H.; Kang, E.Y.; Lee, W.N. Why do we indulge? Exploring motivations for Binge-watching. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2018, 62, 408–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.C. Binge-Watching e a Tríade Negra da Personalidade. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Braga Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, Â.; Vaz, B.B. Portuguese version of the watching TV series motives questionnaire: What does this have to do with loneliness? A bidirectional relationship. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2024, 24, 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Merikivi, J.; Bragge, J.; Scornavacca, E.; Verhagen, T. Binge-watching serialized video content: A transdisciplinary review. Telev. New Media 2020, 21, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starosta, J.A.; Izydorczyk, B. Understanding the Phenomenon of Binge-watching—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starosta, J.A.; Izydorczyk, B.; Lizinczyk, S. Characteristics of people’s Binge-watching behavior in the “entering into early adulthood” period of life. Health Psychol. Rep. 2019, 7, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starosta, J.A.; Izydorczyk, B.; Dobrowolska, M. Personality Traits and Motivation as Factors Associated with Symptoms of Problematic Binge-watching. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.; Kim, K.J. Na exploration of the motivations for Binge-watching and the role of individual diferences. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 82, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. New era of TV-watching behavior: Binge-watching and its Psychological effects. Media Watch 2017, 8, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exelmans, L.; Van den Bulck, J. Binge Viewing, Sleep, and the Role of Pre-Sleep Arausal. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, K., Jr.; Rubenking, B. Go Long or Go Often: Influences on Binge-watching Frequency and Duration among college Students. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M.; Sheehan, K. Sprinting a media marathon: Uses and gratifications of Binge-watching television through Netflix. First Monday 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenking, B.; Bracken, C.C. Binge-watching: A Suspenseful, Emotional, Habit. Commun. Res. Rep. 2018, 35, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.; Lim, S.; Jung, E.E.; Shin, E. I hate Binge-watching but I can’t help doing it: The moderating effect of immediate gratification and need for cognition on Binge-watching attitude-behavior relation. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1971–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, E.; Wirz, D.S.; Eden, A.; Ellithorpe, M.E. Boundaries on a binge: Explicating the role of intentionality in binge-watching motivations and problematic outcomes. Acta Psychol. 2025, 252, 104666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flayelle, M.; Maurage, P.; Billieux, J. Toward a qualitative understanding of Binge-watching behaviors: A focus group approach. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigre-Leirós, V.; Billieux, J.; Mohr, C.; Maurage, P.; King, D.L.; Schimmenti, A.; Flayelle, M. Binge-watching in times of COVID-19: A longitudinal examination of changes in affect and TV series consumption patterns during lockdown. Psychol. Pop. Media 2022, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetrovics, Z.; Griffiths, M.D. Behavioral addictions: Past, present and future. J. Behav. Addict. 2012, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. A “componentes” model of Addiction within a biopsychosocial Framework. J. Subst. Use 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, C.; Brockel, K.L.; Overmeyer, R.; Dieterich, R.; Endrass, T. Neural correlates of response inhibition and performance monitoring in Binge-watching. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2020, 158, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandamudi, V.A.; Sathiyaseelan, A. Binge Watchig: Why are College Students Glued to their Screens? J. Indian Health Psychol. 2018, 12, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. The five-factor model of personality and its relevance to personality disorders. J. Personal. Disord. 1992, 6, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaykamp, G.; Eijck, K.V. Personality, media preferences, and culture participation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 38, 1675–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karumur, R.P.; Nguyen, T.T.; Konstan, J.A. Personality, User Preferences and Behavior in Recommender systems. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 1241–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, L. Implicit acquisition of user personality for argumenting movie recommendations. In User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization; Ricci, F., Bontcheva, K., Conlan, O., Lawless, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.C.; Wang, B.C.; Ji, A.T. The Relationshio Between the Dark Triad and Internet Adaptation Among Adolescents in China: Internet Use Preference as a Mediator. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.L.; Lim, S.X. Predicting internet addiction with the dark triad: Beyond the five-factor model. Psychol. Pop. Media 2021, 10, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.M.; Stolze, D.; Brand, M. Predictors of social-zapping behavior: Dark Triad, impulsivity, and procrastination contribute to the tendency toward last-minute cancellations. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircaburun, K.; Griffiths, M.D. Instagram addiction and the Big Five of personality: The mediating role of self-liking. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.; Bryant, K. Instagram: Motives for its use and relationship to narcissism and contextual age. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrastro, V.; Calaresi, D.; Giordano, F.; Saladino, V. Vulnerable Narcissism and Emotion Dysregulation as Mediators in the Link between Childhood Emotional Abuse and Binge Watching. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2628–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, Z.; Wegmann, E.; Griffiths, M.D. The association between problematic social networking site use, dark triad traits, and emotion dysregulation. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moor, L.; Anderson, J.R. A systematic literature review of the relationship between dark personality traits and antisocial online behaviors. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 144, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.L.; Morshidi, I.; Yoong, L.C.; Thian, K.N. The role of the dark tetrad and impulsivity in social media addiction: Findings from Malaysia. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 143, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.L. Predicting SNS Addiction with the Big Five and the Dark Triad. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2019, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauk, E.; Dieterich, R. Addiction and the Dark Triad of Personality. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eksi, F. Examination of Narcissistic Personality Traits’Predicting Level of Internet Addiction and Cyber Bullying through Path Analysis. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2012, 12, 1694–1706. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos, M.; Naranjo-Zolotov, M.; Aparício, M. Binge-watching Uncovered: Examining the interplay of perceived usefulness, habit, and regret in continuous viewing. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoire, J. ITC guidelines for translating and adapting tests. Int. J. Test. 2018, 18, 101–134. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology 1980, 2, 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Flayelle, M.; Canale, N.; Vögele, C.; Karila, L.; Maurage, P.; Billieux, J. Assessing Binge-watching behaviors: Development and validation of the “Watching TV Series Motives” and “Binge-watching Engagement and Symptoms” questionnaires. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P.K.; Webster, G.D. The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechorro, P.; Jonason, P.K.; Raposo, V.; Maroco, J. Dirty Dozen: A concise measure of Dark Triad traits among at-risk youths. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 3522–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, R.M. Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific software international: Skokie, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, I.; Huang, Y.; Chen, J.; Benesty, J.; Benesty, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Cohen, I. Pearson correlation coefficient. In Noise Reduction in Speech Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flayelle, M.; Maurage, P.; Di Lorenzo, K.R.; Vogele, C.; Gainsbury, S.M.; Billieux, J. Binge-watching: What Do We Know So Far? A First Systematic Review of the Evidence. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2020, 7, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A.; McCoach, D.B. Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 2003, 10, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flayelle, M.; Maurage, P.; Karila, L.; Vögele, C.; Billieux, J. Overcoming the unitary exploration of Binge-watching: A cluster analytical approach. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spangler, T. Binge Nation: 70% of Americans Engage in Marathon TV Viewing. Variety. Available online: https://variety.com/2016/digital/news/Binge-watching-usstudy-deloitte-1201737245/adresindenalındı (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Pittman, M.; Steiner, E. Transportation or narrative completion? Attentiveness during Binge-watching moderates regret. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth-Király, I.; Bőthe, B.; Tóth-Fáber, E.; Hága, G.; Orosz, G. Connected to TV series: Quantifying series watching engagement. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, G.; Favieri, F.; Casagrande, M.; Tambelli, R. Personality and Behavioral Inhibition/Activation Systems in Behavioral Addiction: Analysis of Binge-watching. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D.; Rigby, J.M.; Cabral, D.; Nisi, V. The binge-watcher’s journey: Investigating motivations, contexts, and affective states surrounding Netflix viewing. Convergence 2021, 27, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenking, B.; Bracken, C.C. Binge watching and serial viewing: Comparing new media viewing habits in 2015 and 2020. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2021, 14, 100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA (CI) | CFI | IFI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 items, 7 factors first order, 1 factor second order | 633 | 4831.036 | 736 | 6.564 | 0.094 (0.091–0.096) | 0.892 | 0.892 | 0.048 |

| 40 items, 7 factors first order | 633 | 4233.077 | 719 | 5.887 | 0.088 (0.085–0.091) | 0.907 | 0.907 | 0.040 |

| 40 items, 7 factors first order, six correlations between errors | 633 | 3546.655 | 702 | 5.052 | 0.080 (0.077–0.083) | 0.925 | 0.925 | 0.037 |

| χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA (CI) | CFI | IFI | SRMR | Comparisions | Δ RMSEA | Δ CFI | Δ SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural invariance | 5641.744 | 1424 | 3.962 | 0.069 (0.067–0.070) | 0.886 | 0.887 | 0.027 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Metric invariance | 5698.563 | 1457 | 3.911 | 0.068 (0.066–0.070) | 0.886 | 0.887 | 0.028 | Configural vs. metric | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Scalar invariance | 5916.700 | 1497 | 3.952 | 0.068 (0.067–0.070) | 0.886 | 0.887 | 0.038 | Metric vs. scalar | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.010 |

| Error invariance | 6060.482 | 1525 | 3.974 | 0.069 (0.067–0.070) | 0.886 | 0.887 | 0.053 | Scalar vs. error variance | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.015 |

| Pearson’s Correlations | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | α | ω | CR | AVE | Mean (SD) | |

| 1. BWESQ total | 0.86 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 2.31 (0.91) | |||||||

| 2. Loss of control | 0.958 ** | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.83 | 2.11 (1.01) | ||||||

| 3. Engagement | 0.973 ** | 0.913 ** | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.78 | 2.29 (0.94) | |||||

| 4. Dependency | 0.959 ** | 0.958 ** | 0.908 ** | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.88 | 2.12 (1.00) | ||||

| 5. Desire/savoring | 0.900 ** | 0.776 ** | 0.873 ** | 0.797 ** | 0.88 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.77 | 2.61 (0.88) | |||

| 6. Positive emotions | 0.928 ** | 0.827 ** | 0.899 ** | 0.846 ** | 0.893 ** | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.78 | 2.52 (0.90) | ||

| 7. Binge-watching | 0.974 ** | 0.949 ** | 0.933 ** | 0.941 ** | 0.843 ** | 0.874 ** | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.82 | 2.26 (0.98) | |

| 8. Pleasure preservation | 0.933 ** | 0.889 ** | 0.896 ** | 0.895 ** | 0.811 ** | 0.848 ** | 0.904 ** | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 2.24 (1.00) |

| Pearson’s Correlations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | α | ω | CR | AVE | Mean (SD) | |

| 1. DDT total | 0.72 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.52 | 2.13 (0.76) | |||

| 1 Machiavellianism | 0.878 ** | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.66 | 2.27 (0.88) | ||

| 2 Psychopathy | 0.811 ** | 0.585 ** | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.73 | 1.79 (0.83) | |

| 3 Narcissism | 0.866 ** | 0.660 ** | 0.521 ** | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.73 | 2.31 (0.95) |

| Pearson Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skewness | Kurtosis | Tolerance | VIF | DDT Total | Machiavellianism | Psychopathy | Narcissism | |

| 1. BWESQ total | 0.63 | −0.64 | 0.425 ** | 0.339 ** | 0.518 ** | 0.245 ** | ||

| 2. Loss of control | 0.72 | −0.74 | 0.06 | 17.96 | 0.397 ** | 0.306 ** | 0.523 ** | 0.204 ** |

| 3. Engagement | 0.54 | −0.82 | 0.08 | 12.29 | 0.398 ** | 0.315 ** | 0.497 ** | 0.218 ** |

| 4. Dependency | 0.73 | −0.70 | 0.07 | 14.89 | 0.392 ** | 0.296 ** | 0.526 ** | 0.199 ** |

| 5. Desir/savoring | 0.07 | −0.84 | 0.17 | 6.06 | 0.401 ** | 0.346 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.273 ** |

| 6. Positive emotions | 0.15 | −0.82 | 0.14 | 7.41 | 0.418 ** | 0.341 ** | 0.465 ** | 0.271 ** |

| 7. Binge-watching | 0.53 | −0.83 | 0.06 | 16.50 | 0.423 ** | 0.333 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.247 ** |

| 8. Pleasure preservation | 0.46 | −0.94 | 0.15 | 6.76 | 0.410 ** | 0.324 ** | 0.491 ** | 0.242 ** |

| Skewness | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0.24 | ||||

| Kurtosis | −0.62 | −0.74 | −0.44 | −0.75 | ||||

| Tolerance | 0.49 | 0.63 | 0.54 | |||||

| VIF | 2.06 | 1.60 | 1.87 | |||||

| β (t) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWESQ Total | Loss of Control | Engagement | Dependency | Desire/Savoring | Positive Emotions | Binge-Watching | Pleasure Preservation | |

| Gender | −0.09 (−2.45) * | −0.13 (3.52) *** | −0.11 (−3.08) *** | −0.15 (−4.04) *** | −0.13 (−3.49) *** | |||

| Age | −0.15 (−3.71) *** | −0.19 (−4.53) *** | −0.26 (−5.85) *** | −0.19 (−4.46) *** | −0.14 (−3.32) *** | −0.19 (−4.66) *** | ||

| Employment | 0.14 (3.68) *** | 0.09 (2.86) ** | 0.15 (3.73) *** | 0.11 (3.36) *** | 0.15 (3.67) *** | 0.12 (2.98) ** | 0.14 (3.55) *** | 0.17 (4.37) *** |

| Action series | −0.07 (−2.06) ** | −0.10 (−2.89) ** | −0.10 (−2.87) ** | −0.07 (−1.97) * | −0.10 (−2.74) ** | |||

| Horror series | 0.16 (4.28) *** | 0.16 (4.34) *** | 0.18 (4.82) *** | 0.17 (4.61) *** | 0.14 (3.46) *** | 0.09 (2.33) ** | 0.17 (4.47) *** | 0.15 (4.05) *** |

| Comedy series | −0.09 (−2.63) ** | −0.07 (−2.02) * | −0.07 (−2.04) * | −0.11 (−3.18) ** | −0.09 (−2.28) * | −0.08 (−2.18) ** | −0.11 (−2.96) ** | −0.09 (−2.51) * |

| Scientific fiction and fantasy series | 0.16 (4.69) *** | 0.17 (5.03) *** | 0.15 (4.38) *** | 0.15 (4.44) *** | 0.13 (3.77) *** | 0.14 (4.16) *** | 0.14 (4.14) *** | 0.14 (4.30) *** |

| Documentaries | −0.14 (−4.14) *** | −0.15 (4.48) *** | −0.12 (−3.45) *** | −0.16 (−4.84) *** | −0.10 (−2.81) ** | −0.14 (−3.84) *** | −0.13 (−3.84) *** | −0.14 (−4.15) *** |

| Preferences: stimulating | 0.106 (2.54) * | 0.10 (2.46) * | 0.10 (2.55) * | 0.10 (2.44) * | 0.11 (2.79) ** | 0.12 (2.88) ** | 0.13 (3.10) ** | |

| Machiavellianism | 0.09 (2.41) * | 0.18 (4.26) *** | 0.13 (3.13) ** | 0.09 (2.30) * | 0.09 (2.30) * | |||

| Psychopathy | 0.24 (5.85) *** | 0.32 (9.43) *** | 0.30 (8.79) *** | 0.32 (9.45) *** | 0.11 (2.45) * | 0.21 (4.67) *** | 0.26 (6.15) *** | 0.20 (4.79) *** |

| R2adj | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.44 |

| F (2, 606) | 40.55 | 88.94 | 77.24 | 89.23 | 26.73 | 35.76 | 43.78 | 29.46 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leite, Â.; Rodrigues, A.; Lopes, S.; Pereira, A.C. Understanding Binge-Watching: The Role of Dark Triad Traits, Sociodemographic Factors, and Series Preferences. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020054

Leite Â, Rodrigues A, Lopes S, Pereira AC. Understanding Binge-Watching: The Role of Dark Triad Traits, Sociodemographic Factors, and Series Preferences. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(2):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020054

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeite, Ângela, Anabela Rodrigues, Sílvia Lopes, and Ana Catarina Pereira. 2025. "Understanding Binge-Watching: The Role of Dark Triad Traits, Sociodemographic Factors, and Series Preferences" Psychiatry International 6, no. 2: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020054

APA StyleLeite, Â., Rodrigues, A., Lopes, S., & Pereira, A. C. (2025). Understanding Binge-Watching: The Role of Dark Triad Traits, Sociodemographic Factors, and Series Preferences. Psychiatry International, 6(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020054