Intimate Partner Violence in Adolescent Girls: The Role of Impulsivity and Emotional Dysregulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

2.5. Variables and Instruments

2.5.1. Intimate Partner Physical Violence

2.5.2. Impulsivity

2.5.3. Emotional Dysregulation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Descriptive Data and Correlations Between Variables of Interest

3.3. Relationships Between Socio-Demographic Variables and Variables of Interest

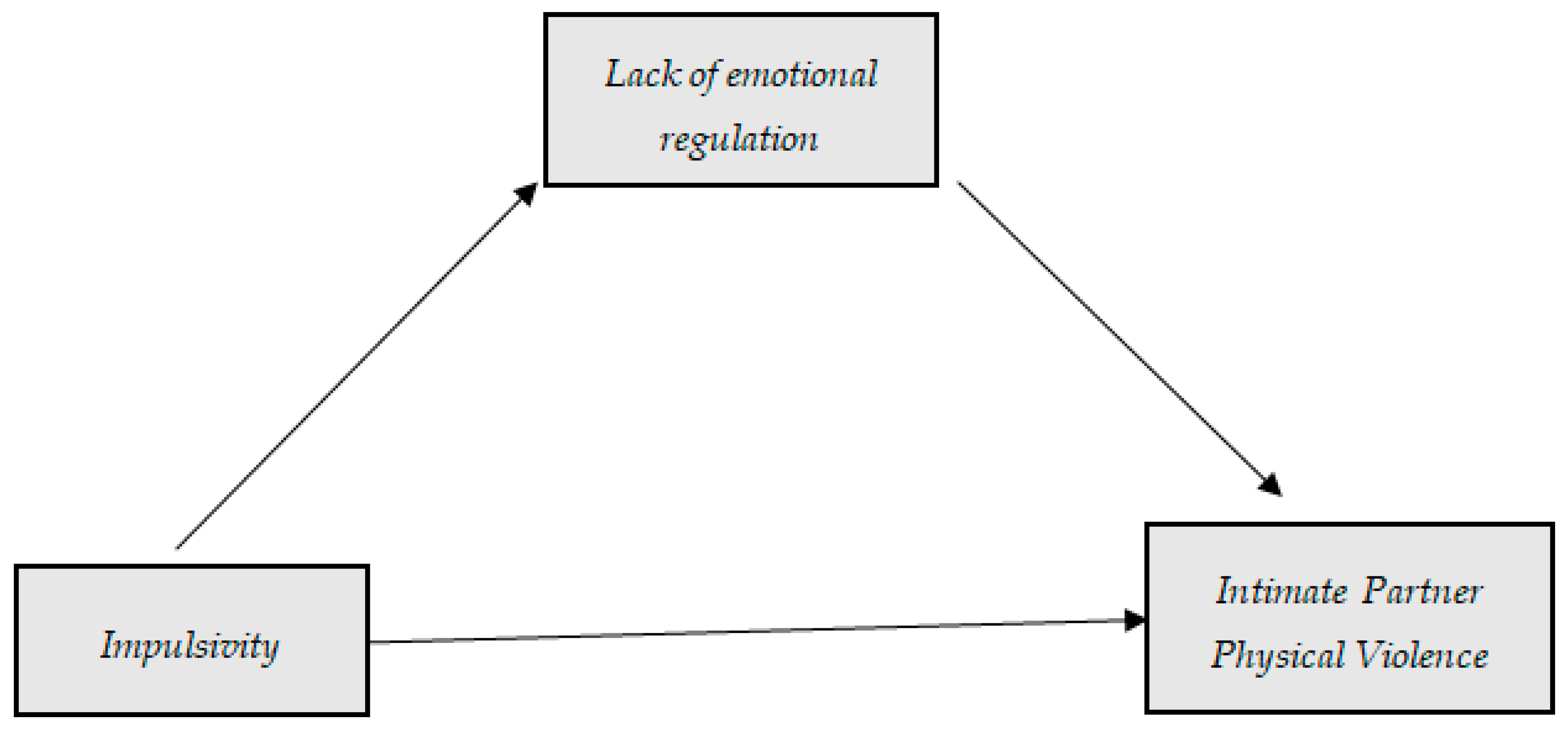

3.4. Mediation Analysis: Influence of Impulsivity on Intimate Partner Physical Violence Through Lack of Emotional Regulation

- (a)

- For physical violence received, the following mediation models (meeting the preconditions) are proposed: impulsivity–DERS Impulse–received violence; impulsivity–DERS Non-acceptance–received violence; impulsivity–DERS Strategies–received violence.

- (b)

- For physical violence perpetrated, the following mediation models (meeting the preconditions) are proposed: impulsivity–DERS Impulse–perpetrated violence; impulsivity–DERS Non-acceptance–perpetrated violence; impulsivity–DERS Goals–perpetrated violence; impulsivity–DERS Strategies–perpetrated violence.

3.4.1. Physical Violence Received

3.4.2. Physical Violence Perpetrated

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Center of Disease Control. Preventing Teen Dating Violence. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/about/about-teen-dating-violence.html (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos. Encuesta de Violencia Contra las Mujeres. 2019. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/violencia-de-genero/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Consejo Nacional para la Igualdad de Género. La Violencia de Género Contra las Mujeres en El Ecuador: Análisis de los Resultados de la Encuesta Nacional Sobre Relaciones Familiares y Violencia de Género Contra las Mujeres. 2014. Available online: https://repositorio.dpe.gob.ec/bitstream/39000/2153/1/VCM-DPE-009-2018.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos, INEC. Estadísticas Sociales y de Salud—Anuario 2010; INEC: Quito, Ecuador, 2010; Available online: https://inec.cr/wwwisis/documentos/INEC/Anuario_Estadistico/Anuario_Estadistico_2010.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Ibáñez, D.B. La violencia de género en Ecuador: Un estudio sobre los universitarios. Rev. Estud. Fem. 2017, 25, 1313–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garita Vílchez, A.I. Nuevas Expresiones de Criminalidad Contra las Mujeres en América Latina y el Caribe: Un Desafío del Sistema de Justicia en El Siglo XXI; Naciones Unidas: Panamá, Republic of Panama, 2013; Available online: https://americalatinagenera.org/violencia-contra-las-mujeres/nuevas-expresiones-de-criminalidad-contra-las-mujeres-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe-un-desafio-del-sistema-de-justicia-en-el-siglo-xxi/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Geneva Smalls Arms Survey. Small Arms Survey 2012: Moving Targets; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; Available online: https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/resource/small-arms-survey-2012-moving-targets (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género. Ministerio de Igualdad, Gobierno de España. 2024. Available online: https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/violenciaencifras/estudios/investigaciones/violencia-en-la-adolescencia/ (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género. Ministerio de Igualdad. Macroencuesta de Violencia de Género Contra la Mujer. 2019. Available online: https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/wp-content/uploads/Macroencuesta_2019_estudio_investigacion.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Taquette, S.R.; Monteiro, D.L.M. Causes and consequences of adolescent dating violence: A systematic review. J. Inj. Violence Res. 2019, 11, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, D.E.; Ball, B.; Houry, D.; Holland, K.M.; Valle, L.A.; Kearns, M.C.; Marshall, K.J.; Rosenbluthet, B.L.C.S.W. In search of teen dating violence typologies. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascardi, M.; Chesin, M.; Kammen, M. Personality correlates of intimate partner violence subtypes: A latent class analysis. Aggress. Behav. 2018, 44, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, Á.; Lila, M.; Moya-Albiol, L. The importance of impulsivity and attention switching deficits in perpetrators convicted for intimate partner violence. Aggress. Behav. 2019, 45, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, T.; Magallon-Neri, E.; Forns, M.; Munoz, D.; Segura, A.; Soler, L.; Planellas, I. Facing interpersonal violence: Identifying the coping profile of poly-victimized resilient adolescents. J. Interp. Violence 2020, 35, 1934–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, M.; Moreau, C.; Blais, M.; Oussaïd, E.; Lavoie, F. A three-step gendered latent class analysis on dating victimization profiles. Psychol. Violence 2019, 9, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamby, S.; Taylor, E.; Jones, L.; Mitchell, K.J.; Turner, H.A.; Newlin, C. From poly-victimization to poly-strengths: Understanding the web of violence can transform research on youth violence and illuminate the path to prevention and resilience. J. Interp. Violence 2018, 33, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.; Fernet, M.; Hébert, M.; Couture, S. Diversity of Profiles and Coping Among Adolescent Girl Victims of Sexual Dating Violence. J. Child Sex Abus. 2023, 32, 596–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvete, E.; Corral, S.; Estevez, A. Cognitive and coping mechanisms in the interplay between intimate partner violence and depression. Anxiety Stress Coping 2007, 20, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, E.D.; Kaltman, S.; Goodman, L.A.; Dutton, M.A. Avoidant coping and PTSD symptoms related to domestic violence exposure A longitudinal study. J. Trauma Stress 2008, 21, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaysen, D.; Dillworth, T.M.; Simpson, T.; Waldrop, A.; Larimer, M.E.; Resnick, P.A. Domestic violence and alcohol use: Trauma-related symptoms and motives for drinking. Add. Behav. 2007, 32, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haesler, L.A. Women’s coping experiences in the spectrum of domestic violence abuse. J. Evid. Based Soc. Work 2013, 10, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg-Looney, L.D.; Perrin, P.B.; Snipes, D.J.; Calton, J.M. Coping styles used by sexual minority men who experience intimate partner violence. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 3687–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neppl, T.K.; Conger, R.D.; Scaramella, L.V.; Ontai, L.L. Intergenerational continuity in parenting behavior: Mediating pathways and child effects. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 1241–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, B.J.; Neppl, T.K.; Senia, J.M.; Schofield, T.J. Understanding adolescent and family influences on intimate partner psychological violence during emerging adulthood and adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 500–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, H.; Azadfallah, P.; Watson, P.; Qaderi, K.; Pasha, A.; Dirmina, F.; Esrafilian, F.; Koulaie, B.; Fayazi, N.; Sepehrnia, N.; et al. Predicting the Social-Emotional competence based on childhood trauma, internalized shame, Disability/Shame scheme, cognitive flexibility, distress tolerance and alexithymia. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2022, 16, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbiola, I.; Estévez, A.I.; López, J.M. Desarrollo y validación del cuestionario VREP (Violencia Recibida, Ejercida y Percibida) en las relaciones de pareja en adolescentes. Apunt. De Psicol. 2021, 38, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosi, S.; Vigil-Colet, A.; Canals, J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Psychometric properties of the Spanish Adaptation of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale11a for children. Psychol. Rep. 2008, 103, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossati Fossati, A.; Barratt, E.S.; Acquarini, E.; Di Ceglie, A. Psychometric properties of and adolescent version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale11 for a sample of italian high school students. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2002, 95, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, J.H.; Stanford, M.S.; Barratt, E.S. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1995, 51, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervás, G.; Jódar, R. Adaptación al castellano de la Escala de Dificultades en la Regulación Emocional. Clínica Y Salud 2008, 19, 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Muñoz, P.; Muñoz Escobar, L.; Velasco Castelo, G. Robustez y potencia de la t-Student para inferencia de una media ante la presencia de datos atípicos. Perfiles 2020, 1, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandica de Roa, E.M. Potencia y robustez en pruebas de normalidad con simulación Montecarlo. Rev. Sci. 2020, 5, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainani, K.L. Dealing with Non-normal Data. PM&R 2020, 12, 977–984. [Google Scholar]

- Poitras, G. Parametric testing for normality against bimodal and unimodal alternatives using higher moments. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2024, 53, 4771–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sardinha, L.; Yüksel-Kaptanoğlu, I.; Maheu-Giroux, M.; García-Moreno, C. Intimate partner violence against adolescent girls: Regional and national prevalence estimates and associated country-level factors. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2024, 8, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos-Gómez, M.; Oliva Delgado, A.; Hernando-Gómez, A. Violencia en relaciones de pareja de jóvenes y adolescentes. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2014, 46, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza-Martínez, M.J.; García-García, M.I.; Zaragoza, L.L.; Ruiz-Hernández, J.A.; Jiménez-Barbero, J.A. Violencia en la pareja adolescente: Diferencias de sexo en función de sus variables predictoras = Adolescence dating violence: Sex differences according to their predictor variables. Rev. Argent. Clín. Psicol. 2019, 28, 937–944. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=psyh&AN=2020-35649-033&site=ehost-live&scope=site (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Derefinko, K.; DeWall, C.N.; Metze, A.V.; Walsh, E.C.; Lynam, D.R. Do different facets of impulsivity predict different types of aggression? Aggress. Behav. 2011, 37, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteside, S.P.; Lynam, D.R. The five-factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers. Individ. Diff. 2001, 30, 669–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, C.; Pereda, N.; Guilera, G.; Abad, J. Internalizing symptoms and polyvictimization in a clinical sample of adolescents: The roles of social support and non-productive coping strategies. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 54, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, M.A.; DiLillo, D.; Messman-Moore, T.L.; Peugh, J.; DeNardi, K.A.; Gaffey, K.J. Severity of child sexual abuse and revictimization: The mediating role of coping and trauma symptoms. Psychol. Women Quart. 2009, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman-Parks, A.M.; DeMaris, A.; Giordano, P.C.; Manning, W.D.; Longmore, M.A. Parents and partners: Moderating and mediating influences on intimate partner violence across adolescence and young adulthood. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2017, 34, 1295–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzolo, K.E.; Roberto, A.J.; Babin, E.A. The relationship between parents’ verbal aggression and young adult children’s intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Díaz, Y.; Guerra Morales, V.M. La regulación emocional y su implicación en la salud del adolescente. Rev. Cuba. Pediatr. 2014, 86, 368–375. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero, E.R.; Herrero, S.P.; Algovia, E.B.; Carrasco, R.V.; Cabrera, J.J. Influencia del apoyo social en el mantenimiento de la convivencia con el agresor en víctimas de violencia de género de León (Nicaragua). Inf. Psicol. 2018, 18, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damonti, P.; Leache, P.A. Las situaciones de exclusión social como factor de vulnerabilidad a la violencia de género en la pareja: Desigualdades estructurales y relaciones de poder de género. EMPIRIA. Rev. Metodol. Cienc. Soc. 2020, 48, 205–230. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/2971/297169772008/297169772008.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, M.; Hébert, M.; Paradis, A. Conflict resolution patterns and violence perpetration in adolescent couples: A gender-sensitive mixed-methods approach. J. Adolesc. 2016, 49, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, L.; Rodríguez-Corcho, J.D. A gender equity and new masculinities approach to development: Examining results from a Colombian case study. Impact Asses. Proj. Apprais. 2022, 40, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, C.J.; Joppa, M.; Barker, C.; Collibee, C.; Zlotnick, C.; Brown, L.K. Project Date SMART: A Dating Violence (DV) and sexual risk prevention program for adolescent girls with prior DV exposure. Prev. Sci. 2018, 19, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heron, R.L.; Eisma, M.; Browne, K. Why Do Female Domestic Violence Victims Remain in or Leave Abusive Relationships? A Qualitative Study. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2022, 31, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fávero, M.; Oliveira, R.; Del Campo, A.; Fernandes, A.; Moreira, D.; Lanzarote-Fernández, M.D.; Sousa-Gomes, V. Intimate Partner Violence: The Relationship Between the Stages of Change, Maintenance Factors, and the Decision to Keep or Leave the Violent Partner. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, A. We Can Do Better: Perspectives on Research and Interventions That Address Sexual, Intimate Partner, Youth, and Community Violence. Psychol. Violence 2024, 14, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Nocentini, A.; Menesini, E.; Pepler, D.; Craig, W.; Williams, T.S. Adolescent dating aggression in Canada and Italy: A cross-national comparison. Intern. J. Behav. Dev. 2010, 34, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Rivas, M.J.; Graña, J.L.; O’Leary, K.D.; González, M.P. Aggression in adolescent dating relationships: Prevalence, justification, and health consequences. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 40, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego JL, C.; Franco, L.R.; Díaz FJ, R.; Molleda, C.B. Violencia en el noviazgo: Revisión bibliográfica y bibliométrica. Arq. Bras. De Psicol. 2014, 66, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fuertes, A.A.; Fuertes, A. Physical and psychological aggression in dating relationships of Spanish adolescents: Motives and consequences. Child Abus. Negl. 2010, 34, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Antón, M.J.; Arribas-Rey, A.; de Miguel, J.M.; García-Collantes, Á. La violencia en las relaciones de pareja de jóvenes: Prevalencia, victimización, perpetración y bidireccionalidad. Rev. Logos Cienc. Tecnol. 2020, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age, Mean (SD) | 15.64 (1.20) |

| Areas, n (%) Rural Urban | 245 (35.1) 455 (64.9) |

| Cohabitation Living with their father, n (%) Living with their mother, n (%) Living with both parents, n (%) Living with your father’s partner, n (%) Living with your mother’s partner, n (%) Living with siblings, n (%) Living with your parent’s partner’s children, n (%) Living with grandparents, n (%) Living with their own partners, n (%) Living alone, n (%) | 499 (71.4) 608 (87) 476 (68.1) 24 (3.4) 70 (10) 523 (74.8) 55 (7.9) 180 (25.8) 68 (9.7) 4 (0.6) |

| Mother’s employment status Works alone on housework, n (%) Working outside the home, n (%) Unemployed, n (%) Pensioner or retired, n (%) Deceased, n (%) I don’t know, n (%) | 483 (69.3) 175 (25.1) 16 (2.3) 3 (0.4) 6 (0.9) 17 (2) |

| Father’s employment status Works alone on housework, n (%) Working outside the home, n (%) Unemployed, n (%) Pensioner or retired, n (%) Deceased, n (%) I don’t know, n (%) | 40 (5.8) 489 (70.6) 51 (7.4) 13 (1.9) 24 (3.5) 83 (10.9) |

| Mother’s level of education * No studies, n (%) Level 1 and 2. Primary education, n (%) Level 3. Secondary education, n (%) Level 4. Post-secondary non-tertiary, n (%) Level 7. University studies, n (%) I don’t know, n (%) | 139 (20) 182 (26.2) 113 (16.3) 84 (12.1) 64 (9.2) 117 (16.3) |

| Father’s level of education * No studies, n (%) Level 1 and 2. Primary education, n (%) Level 3. Secondary education, n (%) Level 4. Post-secondary non-tertiary, n (%) Level 7. University studies, n (%) I don’t know, n (%) | 110 (15.9) 176 (25.5) 112 (16.2) 79 (11.4) 52 (7.5) 170 (23.3) |

| Participants combining work and studies, n (%) | 91 (13) |

| Mean (SD) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Violence Exercised | 10.85 (16.58) | 0.76 ** | 0.20 ** | −0.03 | 0.17 ** | 0.11 * | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.12 ** |

| (2) Violence Received | 11.96 (19.16) | 0.14 ** | −0.02 | 0.16 ** | 0.10 * | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.11 * | |

| (3) Impulsivity | 65.60 (8.69) | 0.04 | 0.43 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.36 ** | ||

| (4) DERS Awareness | 18.47 (5.20) | 0.24 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.09 | 0.29 ** | |||

| (5) DERS Impulse | 14.72 (5.34) | 0.54 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.70 ** | ||||

| (6) DERS Non Accept. | 16.50 (7.25) | 0.57 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.63 ** | |||||

| (7) DERS Goals | 13.86 (4.06) | 0.36 ** | 0.59 ** | ||||||

| (8) DERS Clarity | 13.08 (3.79) | 0.37 ** | |||||||

| (9) DERS Strategies | 16.93 (5.74) |

| Regression of Impulsivity on Violence Received Through Lack of Regulation of Impulsivity (DERS Impulsivity) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: DERS Impulsivity | ||||

| Impulsivity | B (SE) 0.26 (0.02) | t 12.67 | p <0.001 | [LLCI–ULCI] [0.225/0.308] |

| R = 0.44 | R2 = 0.19 | F = 33.52 | p < 0.001 | |

| Outcome variable: Violence received | ||||

| B (SE) | t | p | [LLCI–ULCI] | |

| Impulsivity | 0.28 (0.09) | 3.14 | <0.001 | [0.108/0.467] |

| M: DERS Impulsivity | 0.36 (0.14) | 2.43 | 0.015 | [0.069/0.653] |

| Age | −0.39 (0.60) | −0.646 | 0.518 | [−1.56/0.79] |

| Siblings coexistence | −2.03 (1.65) | −1.23 | 0.218 | [−5.27/1.20] |

| Grandparents coexist. | 0.33 (1.63) | 0.205 | 0.837 | [−2.87/3.54] |

| Working | 2.28 (2.13) | 1.069 | 0.285 | [−1.91/6.47] |

| Model summary | R = 0.21 | R2 = 0.04 | F = 5.35 p < 0.001 | |

| Direct Effect of X on Y | Eff. (SE) 0.28 (0.09) | t 3.14 | p 0.001 | [LLCI–ULCI] [0.108/0.467] |

| Indirect effect of X on Y DERS Impulsivity | Eff. (SE) 0.09 (0.04) | [LLCI–ULCI] [0.016/0.177] | ||

| Regression of Impulsivity on Violence Received Through Non-Acceptance (DERS Non-Acceptance) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: DERS Non-acceptance | ||||

| Impulsivity | B (SE) 0.18 (0.03) | t 5.93 | p <0.001 | [LLCI–ULCI] [0.123/0.245] |

| R = 0.24 | R2 = 0.06 | F = 8.57 | p < 0.001 | |

| Outcome variable: Violence received | ||||

| B (SE) | t | p | [LLCI–ULCI] | |

| Impulsivity | 0.34 (0.08) | 4.01 | <0.001 | [0.172/0.505] |

| M: DERS Non-acceptance | 0.26 (0.10) | 2.53 | 0.011 | [0.057/0.456] |

| Age | −0.48 (0.60) | −0.798 | 0.425 | [−1.65/0.69] |

| Siblings coexistence | −2.03 (1.65) | −1.23 | 0.218 | [−5.28/1.21] |

| Grandparents coexist. | 0.12 (1.64) | 0.076 | 0.939 | [−3.09/3.34] |

| Working | 2.44 (2.13) | 1.142 | 0.253 | [−1.75/6.63] |

| Model summary | R = 0.21 | R2 = 0.04 | F = 5.46 | p < 0.001 |

| Direct Effect of X on Y | Eff. (SE) 0.34 (0.08) | t 4.01 | p <0.001 | [LLCI–ULCI] [0.173/0.505] |

| Indirect effect of X on Y DERS Non-acceptance | Eff. (SE) 0.05 (0.02) | [LLCI–ULCI] [0.011/0.091] | ||

| Regression of Impulsivity on Violence Exercised Through Lack of Regulation of Impulsivity (DERS Impulsivity) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: DERS Impulsivity | ||||

| Impulsivity | B (SE) 0.27 (0.02) | t 12.671 | p <0.001 | [LLCI–ULCI] [0.225/0.308] |

| R = 0.44 | R2 = 0.20 | F = 33.529 | p < 0.001 | |

| Outcome variable: Violence exercised | ||||

| B (SE) | t | p | [LLCI–ULCI] | |

| Impulsivity | 0.36 (0.07) | 4.68 | <0.001 | [0.211/0.516] |

| M: DERS Impulsivity | 0.37 (0.12) | 2.92 | 0.003 | [0.121/0.617] |

| Age | −0.574 (0.51) | −1.127 | 0.260 | [−1.57/0.43] |

| Siblings coexistence | −3.25 (1.40) | −2.32 | 0.020 | [−6.00/−0.51] |

| Grandparents coexistence | −1.78 (1.38) | −1.28 | 0.198 | [−4.51/0.939] |

| Working | 0.389 (1.81) | 0.215 | 0.829 | [−3.17/3.94] |

| Model summary | R = 0.28 | R2 = 0.08 | F = 10.112 | p < 0.001 |

| Direct Effect of X on Y | Eff. (SE) 0.36 (0.08) | t 4.68 | p <0.001 | [LLCI–ULCI] [0.211/0.516] |

| Indirect effect of X on Y DERS Impulsivity | Eff. (SE) 0.10 (0.03) | [LLCI–ULCI] [0.031/0.175] | ||

| Regression of Impulsivity on Violence Exercised Through Non-Acceptance (DERS Non-Acceptance) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: DERS Non-acceptance | ||||

| Impulsivity | B (SE) 0.18 (0.03) | t 5.938 | p <0.001 | [LLCI–ULCI] [0.123/0.245] |

| R = 0.24 | R2 = 0.06 | F = 8.573 | p < 0.001 | |

| Outcome variable: Violence exercised | ||||

| B (SE) | t | p | [LLCI–ULCI] | |

| Impulsivity | 0.42 (0.07) | 5.87 | <0.001 | [0.281/0.563] |

| M: DERS Non-acceptance | 0.23 (0.09) | 2.65 | 0.008 | [0.060/0.398] |

| Age | −0.675 (0.51) | −1.32 | 0.185 | [−1.67/0.326] |

| Siblings coexistence | −3.24 (1.40) | −2.30 | 0.021 | [−5.99/−0.48] |

| Grandparents coexist. | −1.96 (1.39) | −1.40 | 0.160 | [−4.69/0.778] |

| Working | 0.389 (1.81) | 0.215 | 0.829 | [−3.17/3.94] |

| Model summary | R = 0.28 | R2 = 0.08 | F = 9.85 | p < 0.001 |

| Direct Effect of X on Y | Eff. (SE) 0.42 (0.07) | t 5.87 | p <0.001 | [LLCI–ULCI] [0.281/0.563] |

| Indirect effect of X on Y DERS Non-acceptance | Eff. (SE) 0.04 (0.02) | [LLCI–ULCI] [0.008/0.082] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iruarrizaga, I.; Gutiérrez, L.; Olave, L.; Estévez, A.; Muñiz, J.A.; Momeñe, J.; Chávez-Vera, M.D.; Peñacoba, C. Intimate Partner Violence in Adolescent Girls: The Role of Impulsivity and Emotional Dysregulation. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020041

Iruarrizaga I, Gutiérrez L, Olave L, Estévez A, Muñiz JA, Momeñe J, Chávez-Vera MD, Peñacoba C. Intimate Partner Violence in Adolescent Girls: The Role of Impulsivity and Emotional Dysregulation. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(2):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020041

Chicago/Turabian StyleIruarrizaga, Iciar, Lorena Gutiérrez, Leticia Olave, Ana Estévez, José Antonio Muñiz, Janire Momeñe, Maria Dolores Chávez-Vera, and Cecilia Peñacoba. 2025. "Intimate Partner Violence in Adolescent Girls: The Role of Impulsivity and Emotional Dysregulation" Psychiatry International 6, no. 2: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020041

APA StyleIruarrizaga, I., Gutiérrez, L., Olave, L., Estévez, A., Muñiz, J. A., Momeñe, J., Chávez-Vera, M. D., & Peñacoba, C. (2025). Intimate Partner Violence in Adolescent Girls: The Role of Impulsivity and Emotional Dysregulation. Psychiatry International, 6(2), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020041