Mental Health in Croatian Competing Adolescent Athletes: Insights from the SMHAT-1 Questionnaire

Abstract

1. Introduction

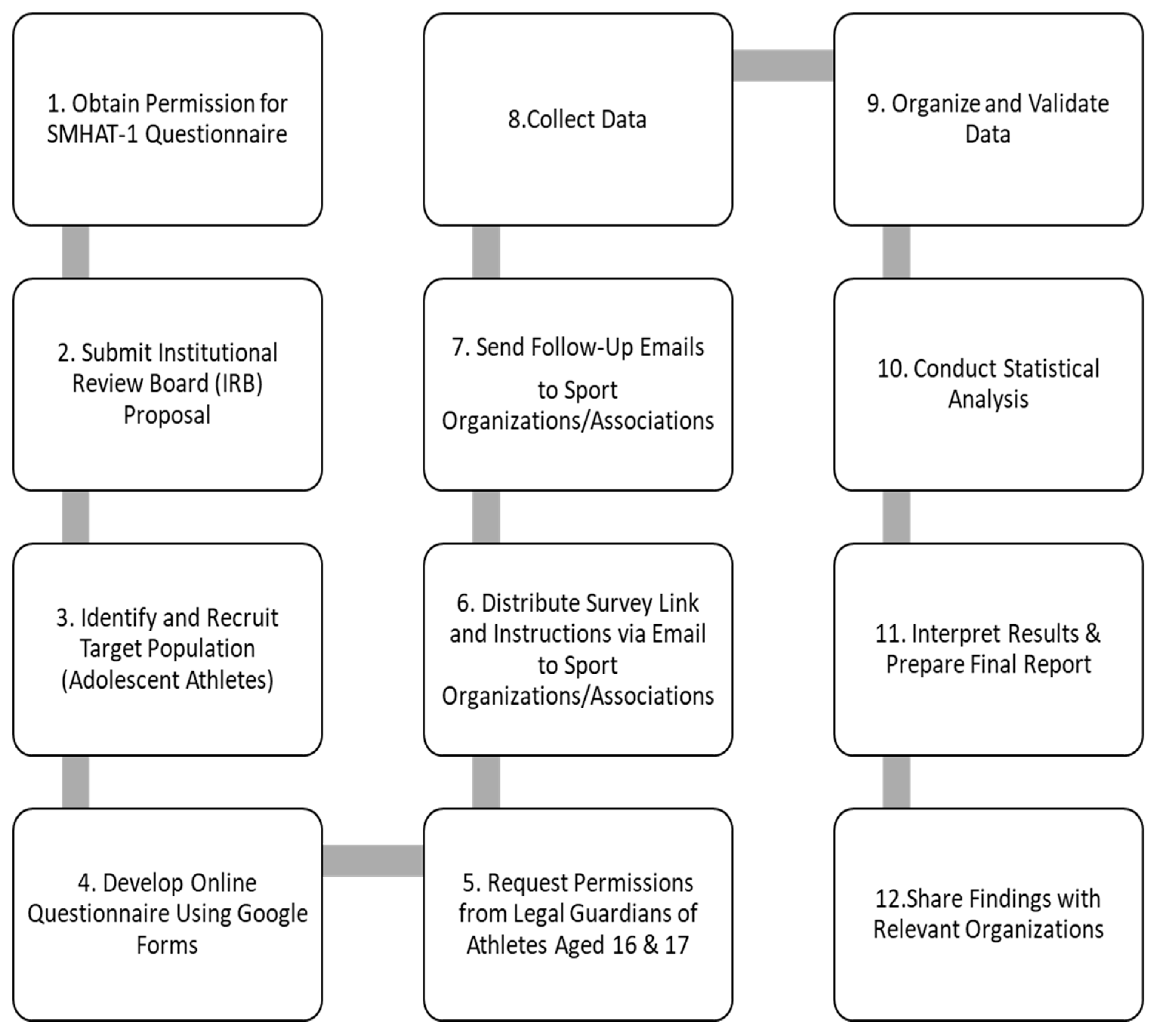

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Study Instrument

- Athlete Psychological Strain Questionnaire (APSQ): Measures psychological strain (maximum score: 50). Athletes who scored ≥17 were classified as above the threshold. The APSQ validated in Croatian was used in this study [21].

- Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD-7): Assesses anxiety levels (range: 0–27). Scores of 5–9 indicate mild anxiety, 10–14 moderate anxiety, and ≥15 severe anxiety. Participants who scored ≥10 were classified as above the threshold [22].

- Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): Tests for depression (range: 0–27). Scores of 5–9 indicate mild depression, 10–14 indicate moderate depression, 15–19 indicate moderatly severe depression, and ≥20 indicate severe depression. Participants who scored ≥10 were categorized as above the threshold [22].

- Athlete Sleep Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ): Assesses sleep disturbances (range: 0–17). Scores of 5–7 represent mild symptoms, 8–14 moderate symptoms, and ≥15 severe symptoms. Values ≥ 8 were classified as above the threshold (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.78).

- Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test—Consumption (AUDIT-C): Tests for alcohol abuse (range: 0–12). Participants who scored ≥4 (men) or ≥3 (women) were classified as above the cut-off [23].

- Cutting Down, Annoyance by Criticism, Guilty Feeling, and Eye-openers Adapted to Include Drugs (CAGE-AID): Measures substance use (except alcohol abuse). The scale consists of four dichotomous items. Participants who scored ≥4 were classified as above the cut-off point [23].

- Brief Eating Disorder in Athletes Questionnaire (BEDA-Q): Assesses eating disorders using nine items with scores ranging from 0 to 3. Scores ≥ 4 were classified as above the cut-off (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.64).

- Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) screening tool: Assesses inattention and hyperactivity (range: 0–6). Participants with a score ≥ 4 were classified as above the cut-off point (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.773).

- Bipolar disorder (BD) scale: Assesses proclivity to manic and depressive episodes. Participants with a score ≥ 7 were classified as above the cut-off point (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.921).

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) screening tool: Assesses exposure to traumatic events and associated symptoms. Scores ≥ 3 indicate a positive screening and were categorized as above the threshold (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.706).

- Screening tool for gambling disorder: Checks for problematic gambling behavior. Scores ≥ 3 indicate moderate gambling problems and were classified as above the threshold (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.815).

- Psychosis screening tool: Assesses symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. Scores ≥ 6 indicate significant symptoms and were categorized as above the threshold (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.922).

2.4. Participants

3. Results and Statistical Analysis

Results

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Implications for Interventions

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Olympic Committee. Mental Health in Elite Athletes: A Consensus Statement. 2021. Available online: https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/bjsports/53/11/667.full.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Hughes, J.; Hargreaves, E.A. Athlete mental health and wellbeing during the transition into elite sport: Strategies to prepare the system. Sports Med.-Open 2024, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Olympic Committee. Mental Health Action Plan. 2021. Available online: https://www.olympic.org/mental-health-action-plan (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Logan, K.; Cuff, S.; LaBella, C.R.; Brooks, M.A.; Canty, G.; Diamond, A.B.; Hennrikus, W.; Moffatt, K.; Nemeth, B.A.; Pengel, K.B.; et al. Organized sports for children, preadolescents, and adolescents. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20190997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgeon, S.; Martin, L.; Rathwell, S.; Camiré, M. The influence of gender on the relationship between the basic psychological needs and mental health in high school student-athletes. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2024, 22, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, C.S.; Hopkins, C.; Kanny, S.; Watson, A. A systematic review of factors associated with sport participation among adolescent females. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Reardon, C.L. The Mental Health of Athletes: Recreational to Elite. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2021, 20, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daley, M.M.; Reardon, C.L. Mental Health in the Youth Athlete. Clin. Sports Med. 2024, 43, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergeron, M.F. The young athlete: Challenges of growth, development, and society. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2010, 9, 356–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderman, E.M.; Breuner, C.C.; Committee on Adolescence; Grubb, L.K.; Powers, M.E.; Upadhya, K.; Wallace, S.B. Unique Needs of the Adolescent. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20193150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelinas, J.; Baillet, S.; Bertrand, O.; Galván, A.; Kolling, T.; Lachaux, J.-P.; Lindenberger, U.; Ribary, U.; Sawa, A.; Uhlhaas, P. Late adolescence: Critical transitions into adulthood. In Late Adolescence: Critical Transitions into Adulthood; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, M.M.; Shoop, J.; Christino, M.A. Mental health in the specialized athlete. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2023, 16, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, M.; Pankowiak, A.; Woessner, M.; Brockett, C.L.; Hanlon, C.; Spaaij, R.; Robertson, S.; McLachlan, F.; Parker, A. Gender-specific psychosocial stressors influencing mental health among women elite and semi-elite athletes: A narrative review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N.; Heinen, T.; Elbe, A.-M. Factors associated with disordered eating and eating disorder symptoms in adolescent elite athletes. Sports Psychiatry 2022, 1, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.; Froehle, A. Examining the incidence of reporting mental health diagnosis between college student athletes and non-athlete students and the impact on academic performance. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 71, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, C.C.; Rice, S.; Gao, C.X.; Butterworth, M.; Clements, M.; Purcell, R. Gender differences in mental health symptoms and risk factors in Australian elite athletes. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2021, 7, e000984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xanthopoulos, M.S.; Benton, T.; Lewis, J.; Case, J.A.; Master, C.L. Mental health in the young athlete. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouttebarge, V.; Bindra, A.; Blauwet, C.; Campriani, N.; Currie, A.; Engebretsen, L.; Hainline, B.; Kroshus, E.; McDuff, D.; Mountjoy, M.; et al. International Olympic Committee (IOC) sport mental health assessment tool 1 (SMHAT-1) and sport mental health recognition tool 1 (SMHRT-1): Towards better support of athletes’ mental health. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 55, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sore, K.; Franic, F.; Androja, L.; Batarelo Kokic, I.; Marčinko, D.; Drmic, S.; Markser, Z.V.; Franic, T. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of the Croatian version of the Athlete Psychological Strain Questionnaire (APSQ). Sports 2024, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić, J.; Skitarelić, N.; Majstorović, D.; Zoranić, S.; Čivljak, M.; Ivanišević, K.; Marendić, M.; Mesarić, J.; Puharić, Z.; Neuberg, M.; et al. Levels of depression, anxiety, and subjective happiness among health sciences students in Croatia: A multi-centric cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovičić Burić, D. Rizični Čimbenici Zlouporabe Alkoholnih Pića Među Šesnaestogodišnjacima u Hrvatskoj. Master’s Thesis, University of Zagreb, School of Medicine, Zagreb, Croatia, 2022. Available online: https://repozitorij.mef.unizg.hr/islandora/object/mef:5155 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Ministry of Tourism and Sport (MTS). National Information System for Sports. 2024. Available online: https://iss.gov.hr/ (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Procjena Stanovništva. 2024. Available online: https://podaci.dzs.hr/2024/hr/76804 (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- European Commission. Special Eurobarometer 472: European Opinion Research Group. 2018. Available online: https://sport.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/special-eurobarometer-472_en.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Calculator.net. Sample Size Calculator. 2024. Available online: https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- UNICEF Croatia. Croatia—Analysis of Gender Issues. 2011. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/croatia/en/reports/croatia-analysis-gender-issues (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Beisecker, L.; Harrison, P.; Josephson, M.; DeFreese, J.D. Depression, anxiety, and stress among female student-athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2024, 58, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison Gutman, L.; Codiroli McMaster, N. Gendered pathways of internalizing problems from early childhood to adolescence and associated adolescent outcomes. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2020, 48, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Volkmar, F.R. (Eds.) Lewis’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook, 5th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wolanin, A.T. Depression in athletes: Incidence, prevalence, and comparisons with the non-athletic population. In Mental Health in the Athlete; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huskey, A.; Kim, K.; Emert, S.; Auerbach, A.; Webb, R.; Skog, M.; Grandner, M.; Taylor, D. Athlete sleep and mental health: Differences by gender, race, and ethnicity. Sleep 2021, 44 (Suppl. S2), A125–A126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halson, S.L.; Johnston, R.D.; Appaneal, R.N.; Rogers, M.A.; Toohey, L.A.; Drew, M.K.; Sargent, C.; Roach, G.D. Sleep quality in elite athletes: Normative values, reliability, and understanding contributors to poor sleep. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F.C.; Driver, H.S. Circadian rhythms, sleep, and the menstrual cycle. Sleep Med. 2007, 8, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2000, 109, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarokh, L.; Short, M.; Crowley, S.J.; Fontanellaz-Castiglione, C.E.; Carskadon, M.A. Sleep and circadian rhythms in adolescence. Curr. Sleep Med. Rep. 2019, 5, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.P.; Ford, D.E.; Mead, L.A.; Cooper-Patrick, L.; Klag, M.J. Insomnia in young men and subsequent depression: The Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 146, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzder, J.; Santhanam-Martin, R.; Rousseau, C. Gender, power, and ethnicity in cultural consultation. In Cultural Consultation: Encountering the Other in Mental Health Care; Kirmayer, L.J., Guzder, J., Rousseau, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babinski, D.E. Sex differences in ADHD: Review and priorities for future research. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2024, 26, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K. Female athletes with ADHD: Time to level the playing field. Br. J. Sports Med. 2024, 58, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzi, I.M.A.; Stival, C.; Gallus, S.; Odone, A.; Barone, L. Exploring patterns of alcohol consumption in adolescence: The role of health complaints and psychosocial determinants in an Italian sample. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Heim, D. Sports and spirits: A systematic qualitative review of emergent theories for student-athlete drinking. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014, 49, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M.; Bishop, D.V.M.; Pine, D.S.; Scott, S.; Stevenson, J.; Taylor, E.; Thapar, A. (Eds.) Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 5th ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Su, X.; Wang, M.; Li, Q.; Shao, Z.; Sun, L. Global, regional, and national burdens of bipolar disorders in adolescents and young adults: A trend analysis from 1990 to 2019. Gen. Psychiatry 2024, 37, e101255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reardon, C.L.; Factor, R.M. Sport psychiatry: A systematic review of diagnosis and medical treatment of mental illness in athletes. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 961–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, C.L. Psychiatric comorbidities in sports. Neurol. Clin. 2017, 35, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akesdotter, C.; Kentta, G.; Eloranta, S.; Franck, J. The prevalence of mental health problems in elite athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olff, M. Sex and gender differences in post-traumatic stress disorder: An update. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2017, 29 (Suppl. S4), 1351204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padaki, A.S.; Noticewala, M.S.; Levine, W.N.; Ahmad, C.S.; Popkin, M.K.; Popkin, C.A. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among young athletes after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. J. Athl. Train. 2020, 55, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, M.; Brackenridge, C.; Arrington, M.; Blauwet, C.; Carska-Sheppard, A.; Fasting, K.; Kirby, S.; Leahy, T.; Marks, S.; Martin, K.; et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement: Harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collomp, K.; Ericsson, M.; Bernier, N.; Buisson, C. Prevalence of prohibited substance use and methods by female athletes: Evidence of gender-related differences. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 839976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloos, A.; Weller, R.A.; Chan, R.; Weller, E.B. Gender differences in adolescent substance abuse. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2009, 11, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.; Robles-Martínez, M.; Tirado-Muñoz, J.; Alías-Ferri, M.; Mestre-Pintó, J.I.; Coratu, A.M.; Torrens, M. A gender perspective of addictive disorders. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2021, 8, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfabbro, P.; King, D.L.; Derevensky, J.L. Adolescent gambling and problem gambling: Prevalence, current issues, and concerns. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2016, 3, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S.; Olive, L.; Gouttebarge, V.; Parker, A.; Clifton, P.; Harcourt, P.; Lloyd, M.; Kountouris, A.; Smith, B.; Busch, B.; et al. Mental health screening: Severity and cut-off point sensitivity of the Athlete Psychological Strain Questionnaire. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 1, 00001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowiec, J.; Banio-Krajnik, A.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Kantanista, A. Eating disorder risk in adolescent and adult female athletes: The role of body satisfaction, sport type, BMI, level of competition, and training background. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Button, T.A.J.; Ouellette, G.P. Actions speak louder than coaches: Eating disorder behaviour among student-athletes. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, A.; Gorczynski, P.; Rice, S.M.; Purcell, R.; McAllister-Williams, R.H.; Hitchcock, M.E.; Hainline, B.; Reardon, C.L. Bipolar and psychotic disorders in elite athletes: A narrative review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Subcategory | Statistics |

|---|---|---|

| Groups | N (%) | |

| Age 16–17 | 104 (15.4) | |

| Age 18–21 | 391 (58.0) | |

| Age 22–24 | 179 (26.5) | |

| Age | Mean ± SD | |

| 20.11 ± 2.30 | ||

| How many hours per week do you practice? | N (%) | |

| 10–16 h | 369 (54.7) | |

| 17+ hours | 305 (45.3) | |

| Gender | N (%) | |

| Male | 418 (62.0) | |

| Female | 256 (38.0) | |

| Education Attainment | N (%) | |

| No elementary school | 2 (0.3) | |

| Elementary school | 177 (26.3) | |

| High school | 455 (67.5) | |

| Baccalaureate degree | 33 (5.0) | |

| University degree | 6 (0.9) | |

| Postgraduate college | 1 (0.1) | |

| Marital Status | N (%) | |

| Not involved in relationship | 394 (58.5) | |

| In relationship | 279 (41.4) | |

| Married | 1 (0.1) | |

| Type of Sport | N (%) | |

| Soccer | 168 (25.0) | |

| Swimming | 147 (21.8) | |

| Athletics | 77 (11.4) | |

| Tennis | 73 (10.8) | |

| Voleyball | 38 (5.6) | |

| Other | 171 (25.4) | |

| How old you were when you started to practice one sport only? | Mean ± SD | |

| 9.64 ± 2.89 | ||

| Sport-Related Injury (Past 12 Months) | N (%) | |

| Yes | 175 (26.0) | |

| No | 499 (74.0) | |

| Participation in Competitions (Last 12 Months) | Mean ± SD | |

| Total | 15.31 ± 11.86 | |

| Next Competition (Days) | Mean ± SD | |

| Total | 17.98 ± 25.88 | |

| Did you ever visit a psychiatrist? | N (%) | |

| Yes | 131 (19.4) | |

| No | 543 (80.5) | |

| Did a psychiatrist ever prescribe you medication? | N (%) | |

| Yes | 60 (8.9) | |

| No | 614 (91.1) |

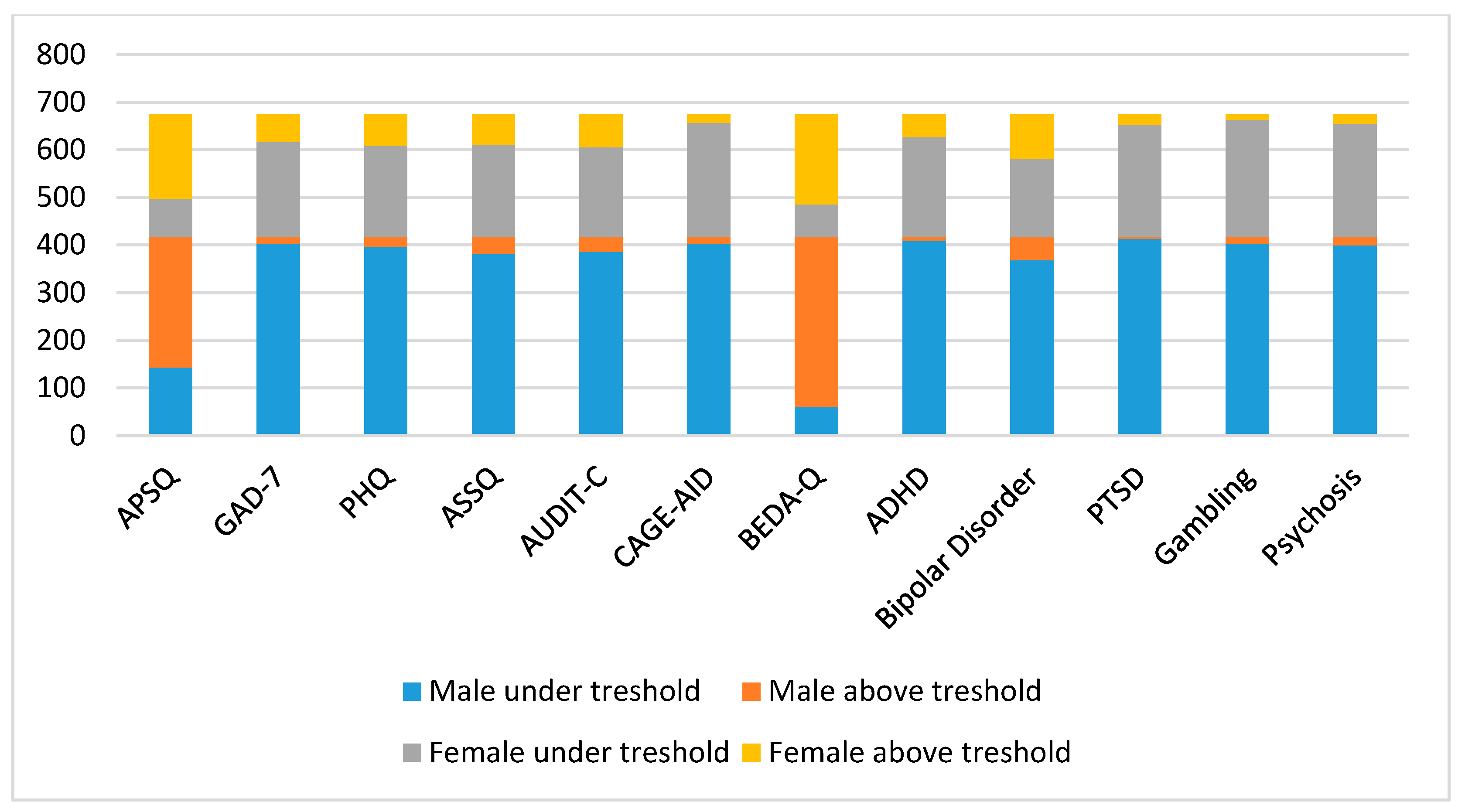

| Test | Gender | Contingency | Chi-Square Tests | Cramér’s V | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under Threshold N (%) | Above Threshold N (%) | Χ2 | df | p | |||

| APSQ | Male | 143 (34.2) | 275 (65.8) | 1.00 | 1 | 0.315 | 0.384 |

| Female | 78 (30.5) | 178 (69.5) | |||||

| Total | 221 (32.8) | 453 (76.2) | |||||

| GAD-7 | Male | 402 (96.2) | 16 (3.8) | 57.59 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.436 |

| Female | 198 (77.3) | 58 (22.7) | |||||

| Total | 600 (89.0) | 74 (11.0) | |||||

| PHQ | Male | 396 (94.7) | 22 (5.3) | 57.21 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.499 |

| Female | 191 (74.6) | 65 (25.4) | |||||

| Total | 587 (87.1) | 87 (12.9) | |||||

| ASSQ | Male | 381 (91.1) | 37 (8.9) | 32.50 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.425 |

| Female | 192 (75.0) | 64 (25.0) | |||||

| Total | 573 (85.0) | 101 (15.0) | |||||

| AUDIT-C | Male | 386 (92.3) | 32 (7.7) | 46.41 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.344 |

| Female | 187 (73.0) | 69 (27.0) | |||||

| Total | 573 (85.0) | 101 (15.0) | |||||

| CAGE-AID | Male | 403 (96.4) | 15 (3.6) | 3.27 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.157 |

| Female | 239 (93.4) | 17 (6.6) | |||||

| Total | 642 (95.3) | 32 (4.7) | |||||

| BEDA-Q | Male | 60 (14.4) | 358 (85.6) | 14.50 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.524 |

| Female | 67 (26.1) | 189 (73.8) | |||||

| Total | 127 (18.8) | 547 (81.1) | |||||

| ADHD | Male | 408 (97.6) | 10 (2.4) | 54.01 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.343 |

| Female | 208 (81.2) | 48 (18.8) | |||||

| Total | 616 (91.4) | 58 (8,6) | |||||

| BD | Male | 368 (88.0) | 50 (12.0) | 54.88 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.431 |

| Female | 164 (64.1) | 92 (35.9) | |||||

| Total | 532 (78.9) | 142 (21.1) | |||||

| PTSD | Male | 413 (98.8) | 5 (1.2) | 21.02 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.249 |

| Female | 235 (91.8) | 21 (8.2) | |||||

| Total | 648 (96.1) | 26 (3.8) | |||||

| Gambling | Male | 403 (96.4) | 15 (3.6) | 0.22 | 1 | 0.64 | 0.196 |

| Female | 245 (95.7) | 11 (4.3) | |||||

| Total | 649 (96.1) | 26 (3.9) | |||||

| Psychosis | Male | 399 (95.5) | 19 (4.5) | 2.47 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.185 |

| Female | 237 (92.6) | 19 (7.4) | |||||

| Total | 636 (94.4) | 38 (5.6) | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sore, K.; Franic, F.; Androja, L.; Batarelo Kokic, I.; Marcinko, D.; Drmic, S.; Markser, V.Z.; Franic, T. Mental Health in Croatian Competing Adolescent Athletes: Insights from the SMHAT-1 Questionnaire. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6010029

Sore K, Franic F, Androja L, Batarelo Kokic I, Marcinko D, Drmic S, Markser VZ, Franic T. Mental Health in Croatian Competing Adolescent Athletes: Insights from the SMHAT-1 Questionnaire. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleSore, Katarina, Frane Franic, Luka Androja, Ivana Batarelo Kokic, Darko Marcinko, Stipe Drmic, Valentin Zdravko Markser, and Tomislav Franic. 2025. "Mental Health in Croatian Competing Adolescent Athletes: Insights from the SMHAT-1 Questionnaire" Psychiatry International 6, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6010029

APA StyleSore, K., Franic, F., Androja, L., Batarelo Kokic, I., Marcinko, D., Drmic, S., Markser, V. Z., & Franic, T. (2025). Mental Health in Croatian Competing Adolescent Athletes: Insights from the SMHAT-1 Questionnaire. Psychiatry International, 6(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6010029