How Important Are Optimism and Coping Strategies for Mental Health? Effect in Reducing Depression in Young People

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

- (a)

- Trait Depression Inventory (T-DEP). Adapted into Spanish by Agudelo et al. [31] This is composed of a total of 16 items, eight for Dysthymia and eight for Euthymia. The items ask to identify the occurrence frequency (trait) for the affective component of depression. The area of content is the frequency of negative affectivity (Dysthymia) and positive affectivity (Euthymia). The final score for depression is obtained by adding the values. The inventory has reliability and validity.

- (b)

- Mexican Optimism Scale (MOS). The MOS [23] consists of 15 items, and is divided into 3 factors: affective resources, positive vision, and hope. It is rated on a 5-point Likert scale with reliability and adequate construct validity.

- (c)

- Coping strategies (CSI-SF). This consists of 16 items on a Likert scale that evaluates strategies focused on commitment and avoidance strategies, as well as two categories of coping, problem solving and resolution through emotion. CIS-SF has been validated for reliability in young people [32].

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations between the Study Variables

3.3. Moderating Effects Analysis

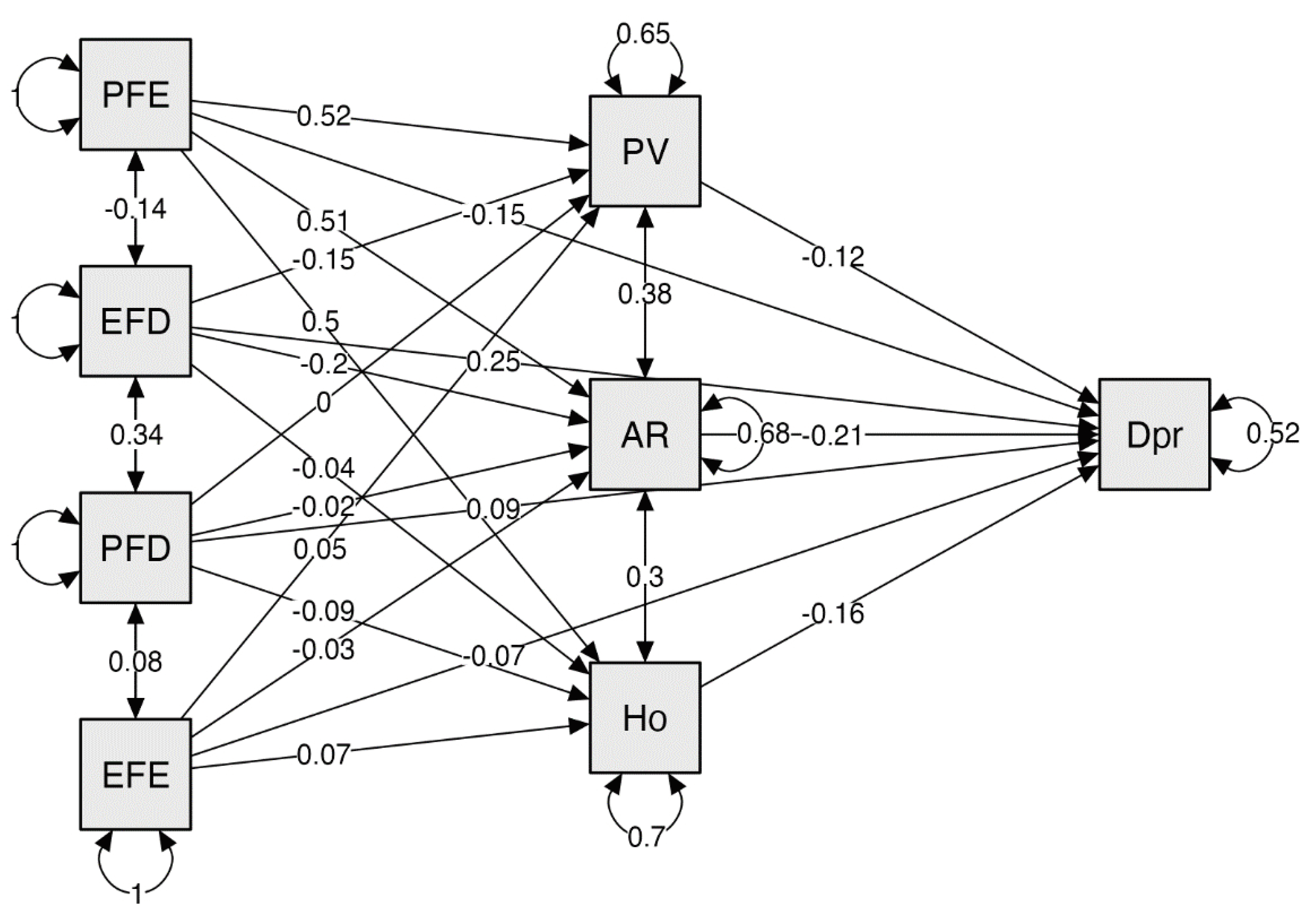

3.4. Direct Effects of Optimism and Coping on Depression

3.5. Indirect Effects of Optimism and Coping on Depression

3.6. Total Indirect Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Informe Mundial Sobre Salud Mental: Transformar la Salud Mental para Todos: Panorama General. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/356118 (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Depression. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Secretaría de Salud. 2° Diagnóstico Operativo de Salud Mental y Adicciones. Secretaría de Salud. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/730678/SAP-DxSMA-Informe-2022-rev07jun2022.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Dia Mundial para la Prevención del Suicidio. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/aproposito/2023/EAP_Suicidio23 (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Luo, J.; Cao, W.; Zhao, J.; Zeng, X.; Pan, Y. The moderating role of optimism between social trauma and depression among Chinese college students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría. Guía de Consulta de los Criterios Diagnósticos del DSM 5; Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-89042-551-0. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Tripartite Model of Anxiety and Depression: Psychometric Evidence and Taxonomic Implications. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1991, 100, 316–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nima, A.A.; Rosenberg, P.; Archer, T.; Garcia, D. Anxiety, Affect, Self-Esteem, and Stress: Mediation and Moderation Effects on Depression. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 0-8261-4191-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, J.S.R.; Staten, R.T.; Hall, L.A.; Lennie, T.A. The Relationship among Young Adult College Students’ Depression, Anxiety, Stress, Demographics, Life Satisfaction, and Coping Styles. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustems-Carnicer, J.; Calderón, C. Coping strategies and psychological well-being among teacher education students. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2013, 28, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E.; Stanton, A.L. Coping Resources, Coping Processes, and Mental Health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 3, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romswinkel, E.V.; König, H.H.; Hajek, A. The role of optimism in the relationship between job stress and depressive symptoms. Longitudinal findings from the German Ageing Survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 241, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Su, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, W. Optimism, Social Identity, Mental Health: Findings Form Tibetan College Students in China. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 747515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Segerstrom, S.C. Optimism. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G.; Yıldırım, M. Coronavirus stress, meaningful living, optimism, and depressive symptoms: A study of moderated mediation model. Aust. J. Psychol. 2021, 73, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P. Relationship between perceived psychological stress and depression: Testing moderating effect of dispositional optimism. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2012, 27, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.; Xu, X.; Hong, X.; Yuan, J. Higher socioeconomic status predicts less risk of depression in adolescence: Serial mediating roles of social support and optimism. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenglass, R.E.; Fiksenbaum, L. Proactive coping, positive affect, and well-being: Testing for mediation using path analysis considerations. Eur. Psychol. 2009, 14, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenglass, E.; Fiksenbaum, l.; Eaton, J. The relationship between coping social support, functional disability and depression in the elderly. Anxiety Stress Coping 2006, 19, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, K.W.C.; Chan, C.K.; Ip, P.K.Y.; Ma, S.Y.K.; Tsai, W.W.; Wong, C.S.; Wong, C.H.T.; Wong, T.W.; Yan, D. Depression and anxiety among university students in Hong Kong. HKMJ 2018, 24, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, L. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and its correlations with positive psychological variables among Chinese medical students: An exploratory cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Delgado, J.; Acevedo-Ibarra, J.N. Psychometric Properties of a New Mexican Optimism Scale: Ethnopsychological Approach. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 2747–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissette, I.; Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S. The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nes, L.S.; Segerstrom, S.C. Dispositional Optimism and Coping: A Meta-Analytic Review. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achat, H.; Kawachi, I.; Spiro, A.; DeMolles, D.A.; Sparrow, D. Optimism and depression as predictors of physical and mental health functioning: The Normative Aging Study. Ann. Behav. Med. 2000, 22, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, C.L.; Schwartz, S.J.; Salas-Wright, C.P.; Pinedo, M.; Martinez, P.; Meca, A.; Isaza, A.G.; Lorenzo-Blanco, E.I.; McClure, H.; Marsiglia, F.F.; et al. Alcohol use severity, depressive symptoms, and optimism among Hispanics: Examining the immigrant paradox in a serial mediation model. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 2329–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, J.L.; Connolly, S.L.; Liu, R.T.; Stange, J.P.; Abramson, L.Y.; Alloy, L.B. It gets better: Future orientation buffers the development of hopelessness and depressive symptoms following emotional victimization during early adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2015, 43, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rincón, U.A.; Botelho, S.; Gouveia, J.; da Silva, J. Association between the dispositional optimism and depression in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psicol. Reflex. Crit. 2021, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, K.S.; Vogeltanz, N.D. Dispositional optimism as a predictor of depressive symptoms over time. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2000, 28, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, D.; Carretero-Dios, H.; Blanco Picabia, A.; Pitti, C.; Spielberger, C.; Buela-Casal, G. Evaluación del componente afectivo de la depresión: Análisis factorial del ST/DEP revisado. Salud Ment. 2005, 28, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tous-Pallarés, J.; Espinoza-Díaz, I.M.; Lucas-Mangas, S.; Valdivieso-León, L.; Gómez-Romero, M.D.R. CSI-SF: Propiedades psicométricas de la versión española del inventario breve de estrategias de afrontamiento. An. Psicol. 2022, 38, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud. Reglamento de la Ley General de Salud en Materia de Investigación para la Salud. 2011. Available online: http://www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/cdi/nom/compi/rlgsmis.html (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Belsley, D.A. Assessing the presence of harmful collinearity and other forms of weak data through a test for signal-to-noise. J. Econom. 1982, 20, 211–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-60918-230-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lacobucci, D.; Saldanha, N.; Deng, X. A meditation on mediation: Evidence that structural equations models perform better than regressions. J. Consum. Psychol. 2007, 17, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Conditional Process Analysis: Concepts, computation, and advances in the Modeling of the Contingencies of Mechanisms. Am. Behav. Sci. 2020, 64, 19–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafogianni, C.; Pappa, D.; Mangoulia, P.; Kourti, F.E.; Koutelekos, I.; Dousis, E.; Margari, N.; Ferentinou, E.; Stavropoulou, A.; Gerogianni, G.; et al. Anxiety, Stress and the Resilience of University Students during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2573–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkul, B.; Günüşen, N.P. Stressors and Coping Methods of Turkish Adolescents With High and Low Risk of Depression: A Qualitative Study. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2020, 27, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanjie, T.; Qian, D. Depressive symptoms among first-year Chinese undergraduates: The roles of socio-demographics, coping style, and social support. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, J.G.; Cao, X.Y.; Cao, Y.; Shi, Y.F.; Wang, Y.N.; Yan, C.; Abela, J.R.Z.; Gan, Y.Q.; Gong, Q.Y.; Chan, R.C.K. Coping flexibility in college students with depressive symptoms. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, M.G.; Pfeiffer, S.; Spence, S.H. Life events, coping and depressive symptoms among young adolescents: A one-year prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 117, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussong, A.M.; Miggette, A.J.; Thomas, T.E.; Coffman, J.L.; Cho, S. Coping and Mental Health in Early Adolescence during COVID-19. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021, 49, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, D.L.; Holroyd, K.A.; Reynolds, R.V.; Wigal, J.K. The Hierarchical Factor Structure of the Coping Strategies Inventory. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1989, 13, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karing, C. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety, depression and stress among university students during the period of the first lockdown in Germany. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 5, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S.; Bridges, M.W. Optimism, pessimism, and psychological well-being. In Optimism & Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice; Chang, E.C., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 189–216. ISBN 1-55798-691-6. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sex—gender | ||

| Men | 410 | 48.3 |

| Women | 438 | 51.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 783 | 92.3 |

| Married | 32 | 3.8 |

| Free union | 33 | 3.9 |

| Profession | ||

| Health sciences | 394 | 46.5 |

| Social sciences | 67 | 7.9 |

| Arts and humanities | 101 | 11.9 |

| Business | 110 | 13.0 |

| Tourism and gastronomy | 15 | 1.8 |

| Engineering | 125 | 14.7 |

| No profession | 36 | 4.2 |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 508 | 59.9 |

| Worker | 85 | 10 |

| Student and worker | 255 | 30.1 |

| Region of residence | ||

| North | 602 | 71 |

| South | 215 | 24.5 |

| Center | 31 | 3.7 |

| PV | AR | H | PFE | EFD | PFD | EFE | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | −0.537 *** | −0.559 *** | −0.503 *** | −0.478 *** | 0.433 *** | 0.232 *** | −0.297 *** | 31.42 | 8.2 |

| Positive Vision | _ | 0.712 *** | 0.608 ** | 0.566 ** | −0.244 ** | −0.074 * | 0.295 ** | 21.09 | 4.6 |

| Affective Resources | — | 0.594 ** | 0.524 *** | −0.277 *** | −0.112 ** | 0.212 *** | 16.47 | 3.77 | |

| Hope | — | 0.535 *** | −0.162 *** | −0.119 ** | 0.273 *** | 22.84 | 4.5 | ||

| Problem Focused Engagement | — | −0.145 ** | −0.041 | 0.396 *** | 13.51 | 2.5 | |||

| Emotional Focused Disengagement | 0.339 *** | −0.222 *** | 12.61 | 3.0 | |||||

| Problem Focused Disengagement | 0.076 * | 10.52 | 3.0 | ||||||

| Emotion Focused Engagement | 12.43 | 3.7 |

| Confidence Intervals 95% | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Variables | β | SE | Z | Lower | Upper | ||

| PV | → | Depression | −0.121 | 0.039 | −3.13 ** | −0.197 | −0.045 |

| AR | → | Depression | −0.207 | 0.038 | −5.94 *** | −0.281 | −0.133 |

| Hope | → | Depression | −0.155 | 0.034 | −4.59 *** | −0.222 | −0.089 |

| PFE | → | Depression | −0.059 | 0.013 | −4.60 *** | −0.084 | −0.034 |

| EFD | → | Depression | −0.082 | −0.009 | 8.98 *** | 0.064 | 0.100 |

| PFD | → | Depression | 0.031 | 0.009 | 3.52 *** | 0.014 | 0.048 |

| EFE | → | Depression | −0.018 | 0.008 | −2.34 *** | −0.032 | −0.003 |

| PFE | → | Affective resources | 0.196 | 0.012 | 16.31 *** | 0.173 | 0.220 |

| EFD | → | Affective resources | −0.066 | 0.010 | −6.50 *** | −0.086 | −0.046 |

| PFD | → | Affective resources | −0.007 | 0.010 | −0.64 | −0.026 | 0.013 |

| EFE | → | Affective resources | −0.008 | 0.009 | −0.98 | −0.025 | 0.008 |

| PFE | → | Positive vision | 0.202 | 0.012 | 17.28 *** | 0.179 | 0.225 |

| EFD | → | Positive vision | −0.051 | 0.010 | −5.07 *** | −0.070 | −0.031 |

| PFD | → | Positive vision | −0.001 | 0.010 | −0.128 | −0.021 | −0.018 |

| EFE | → | Positive vision | −0.015 | 0.008 | 1.75 | −0.002 | 0.031 |

| PFE | → | Hope | 0.192 | 0.012 | 15.82 *** | 0.169 | 0.216 |

| EFD | → | Hope | −0.014 | 0.010 | −1.39 | −0.035 | 0.006 |

| PFD | → | Hope | −0.029 | 0.010 | −2.86 ** | −0.049 | −0.009 |

| EFE | → | Hope | 0.015 | 0.008 | 1.75 | −0.002 | 0.031 |

| Confidence Intervals 95% | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Variables | β | SE | Z | Lower | Upper | ||||

| PFE | → | PV | → | Depression | −0.002 | 0.008 | −3.08 * | −0.040 | −0.009 |

| PFE | → | AR | → | Depression | −0.410 | 0.008 | 5.20 *** | −0.056 | −0.025 |

| PFE | → | Ho | → | Depression | −0.030 | 0.007 | −4.41 ** | −0.043 | −0.017 |

| EFD | → | PV | → | Depression | 0.006 | 0.002 | 2.65 ** | 0.002 | 0.011 |

| EFD | → | AR | → | Depression | 0.014 | 0.003 | 4.19 *** | 0.007 | 0.020 |

| EFD | → | Ho | → | Depression | 0.002 | 0.002 | 1.33 | −0.001 | 0.006 |

| PFD | → | PV | → | Depression | 0.006 | 0.002 | 2.66 ** | 0.002 | 0.011 |

| PFD | → | AR | → | Depression | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.55 | −0.003 | 0.005 |

| PFD | → | Ho | → | Depression | 0.005 | 0.002 | 2.43 | 0.000 | 0.008 |

| EFE | → | PV | → | Depression | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.92 | −0.002 | 0.005 |

| EFE | → | AR | → | Depression | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.97 | −0.002 | −1.21 |

| EFE | → | Ho | → | Depression | −0.003 | 0.001 | −2.04 * | −0.006 | −2.21 |

| Confidence Intervals 95% | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Variables | β | SE | Z | Lower | Upper | ||

| PFE | → | Depression | −0.245 | 0.023 | −10.63 *** | −0.290 | −0.200 |

| EFD | → | Depression | 0.068 | 0.016 | 4.25 *** | 0.037 | 0.99 |

| PFD | → | Depression | 0.018 | 0.013 | 1.37 | −0.008 | 0.044 |

| EFE | → | Depression | −0.011 | 0.014 | −0.89 | −0.039 | −0.015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palacios-Delgado, J.; Acosta-Beltrán, D.B.; Acevedo-Ibarra, J.N. How Important Are Optimism and Coping Strategies for Mental Health? Effect in Reducing Depression in Young People. Psychiatry Int. 2024, 5, 532-543. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint5030038

Palacios-Delgado J, Acosta-Beltrán DB, Acevedo-Ibarra JN. How Important Are Optimism and Coping Strategies for Mental Health? Effect in Reducing Depression in Young People. Psychiatry International. 2024; 5(3):532-543. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint5030038

Chicago/Turabian StylePalacios-Delgado, Jorge, Delia Brenda Acosta-Beltrán, and Jessica Noemí Acevedo-Ibarra. 2024. "How Important Are Optimism and Coping Strategies for Mental Health? Effect in Reducing Depression in Young People" Psychiatry International 5, no. 3: 532-543. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint5030038

APA StylePalacios-Delgado, J., Acosta-Beltrán, D. B., & Acevedo-Ibarra, J. N. (2024). How Important Are Optimism and Coping Strategies for Mental Health? Effect in Reducing Depression in Young People. Psychiatry International, 5(3), 532-543. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint5030038