Life Intricacies of Sex Workers: An Integrative Review on the Psychiatric Challenges Faced by Sex Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review Methodology

2.1. Problem Identification

- (1)

- What are the prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders among sex workers, and what are the primary risk factors contributing to their mental health challenges?

- (2)

- How do experiences of stigma, discrimination, and trauma impact the mental health of sex workers?

2.2. Literature Search

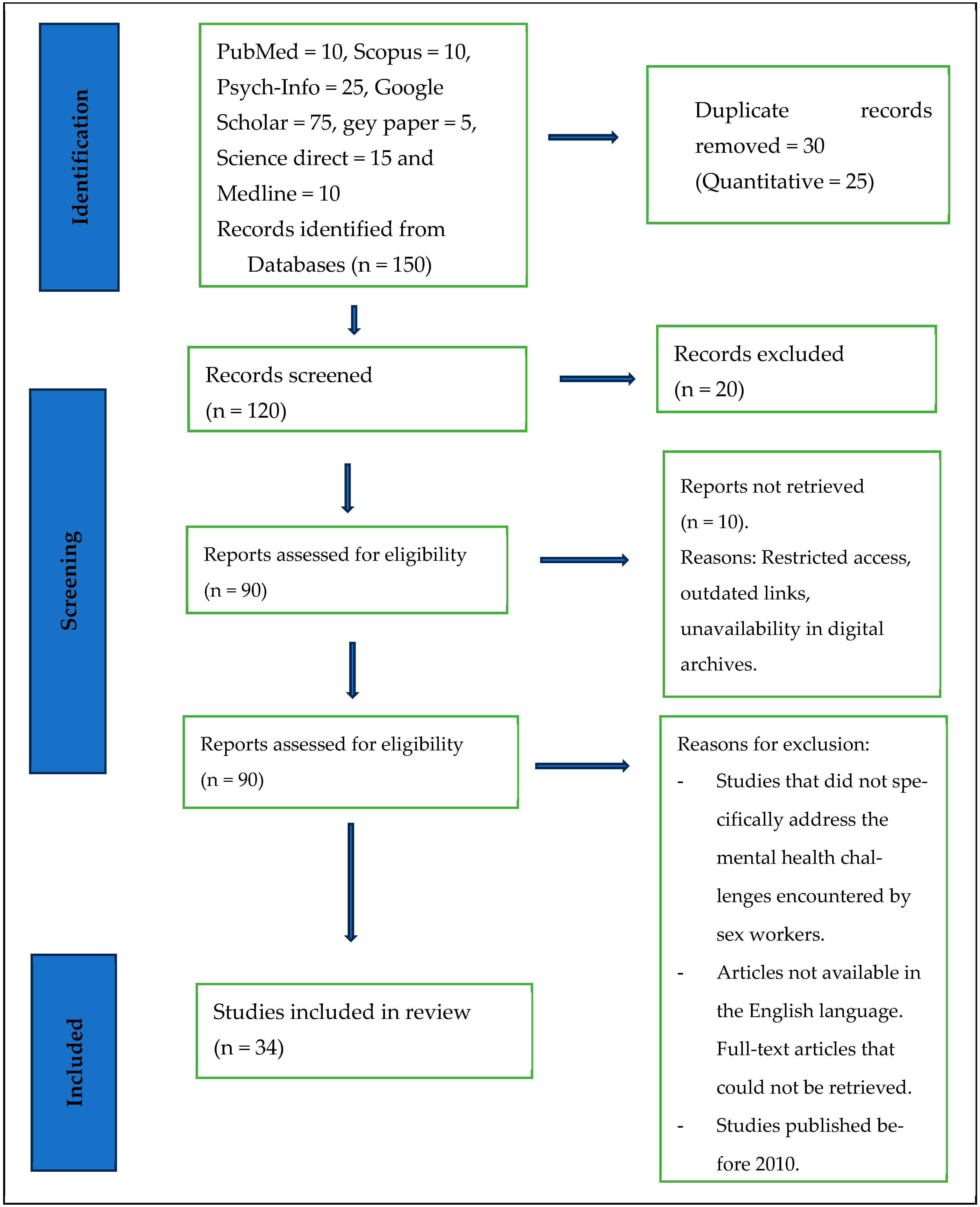

- Restricted access: some articles were behind paywalls or required institutional access, which was unavailable to the researchers conducting this review.

- Outdated links: in some cases, the URLs provided for accessing the full texts were outdated or no longer functional, making it impossible to retrieve the articles.

- Unavailability in digital archives: certain articles were unavailable in digital archives or online repositories, making it challenging to obtain them through standard search methods.

- Lack of response: attempts were made to contact authors or publishers to request access to the full texts of the article, but in some instances, there was no response, or the requests were denied.

- Limited availability: some articles may have been published in journals not indexed in the electronic databases searched for this review, resulting in their unavailability through the initial search strategy.

- Inclusion criteria

- Exclusion criteria

- Studies that did not specifically address the mental health challenges encountered by sex workers.

- Articles not available in the English language.

- Full-text articles that could not be retrieved.

- Studies published before 2010.

2.3. Data Evaluation and Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

2.5. Presentation of Data

3. Results

- Theme 1. Mental health challenges faced by sex workers

- Subtheme 1.1: Mental disorders

- Depression

- Anxiety

- PTSD

- Suicidal ideation and substance abuse disorder

- Theme 2: Primary risk factors contributing to their mental health challenges

- Subtheme 2.1 Work and personal associated factors.

4. Discussion

5. Policy Implications

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Puri, N.; Shannon, K.; Nguyen, P.; Goldenberg, S.M. Burden and correlates of mental health diagnoses among sex workers in an urban setting. BMC Women’s Health 2017, 17, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehnder, M.; Mutschler, J.; Rössler, W.; Rufer, M.; Rüsch, N. Stigma as a barrier to mental health service use among female sex workers in Switzerland. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 432334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, E. Sexual Exploitation and Prostitution and Its Impact on Gender Equality; EPRS: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjbar, F.; Sadeghi-Bazargani, H.; Pishgahi, A.; Nobari, O.; Farahbakhsh, M.; Farhang, S.; Adlnasab, L.; Dareshiri, S. Mental health status among female sex workers in Tabriz, Iran. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2019, 22, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millan-Alanis, J.M.; Carranza-Navarro, F.; de León-Gutiérrez, H.; Leyva-Camacho, P.C.; Guerrero-Medrano, A.F.; Barrera, F.J.; Garza Lopez, L.E.; Saucedo-Uribe, E. Prevalence of suicidality, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety among female sex workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2021, 24, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanayama, Y.; Yamada, H.; Yoshikawa, K.; Aung, K.W. Mental health status of female sex workers exposed to violence in Yangon, Myanmar. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2022, 34, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beksinska, A.; Shah, P.; Kungu, M.; Kabuti, R.; Babu, H.; Jama, Z.; Panneh, M.; Nyariki, E.; Nyabuto, C.; Okumu, M.; et al. Longitudinal experiences and risk factors for common mental health problems and suicidal behaviours among female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. Glob. Ment. Health 2022, 9, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panneh, M.; Gafos, M.; Nyariki, E.; Liku, J.; Shah, P.; Wanjiru, R.; Wanjiru, M.; Beksinska, A.; Pollock, J.; Maisha Fiti Study Champions; et al. Mental health challenges and perceived risks among female sex Workers in Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, T.S.; Smilenova, B.; Krishnaratne, S.; Mazzuca, A. Mental health problems among female sex workers in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rössler, W.; Koch, U.; Lauber, C.; Hass, A.; Altwegg, M.; Ajdacic-Gross, V.; Landolt, K. The mental health of female sex workers. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2010, 122, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengartner, M.P.; Islam, N.; Haker, H.; Rössler, W. Mental health and functioning of female sex workers in Chittagong, Bangladesh. Front. Psychiatry 2015, 6, 166557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagtani, R.A.; Bhattarai, S.; Adhikari, B.R.; Baral, D.; Yadav, D.K.; Pokharel, P.K. Violence, HIV risk behaviour and depression among female sex workers of eastern Nepal. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puras, D. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. Philipp. Law J. 2022, 95, 274. [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal-Blog, V. Protection against Violence and Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity; United Nations General Assembly [UNGA]: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Y. Partner violence and psychosocial distress among female sex workers in China. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Tanck, D. Impact of Debt on Women’s and Girls’ Human Rights–Introduction to the 2023 Report of the UN Working Group on Discrimination against Women and Girls, ‘Gendered Inequalities of Poverty: Feminist and Human Rights-Based Approaches’. In Feminism in Public Debt; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2024; pp. 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Hong, Y.; Su, S.; Zhou, Y. Relationship between female sex workers and gatekeeper: The impact on female sex worker’s mental health in China. Psychol. Health Med. 2014, 19, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duff, P.; Sou, J.; Chapman, J.; Dobrer, S.; Braschel, M.; Goldenberg, S.; Shannon, K. Poor working conditions and work stress among Canadian sex workers. Occup. Med. 2017, 67, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwood, J.A.; Grosso, A.; Decker, M.R.; Peitzmeier, S.; Papworth, E.; Diouf, D.; Drame, F.M.; Ceesay, N.; Baral, S. Sexual violence against female sex workers in The Gambia: A cross-sectional examination of the associations between victimization and reproductive, sexual and mental health. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewkes, R.; Milovanovic, M.; Otwombe, K.; Chirwa, E.; Hlongwane, K.; Hill, N.; Mbowane, V.; Matuludi, M.; Hopkins, K.; Gray, G.; et al. Intersections of sex work, mental ill-health, IPV and other violence experienced by female sex workers: Findings from a cross-sectional community-centric national study in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beksinska, A.; Jama, Z.; Kabuti, R.; Kungu, M.; Babu, H.; Nyariki, E.; Shah, P.; Maisha Fiti Study Champions; Nyabuto, C.; Okumu, M.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of common mental health problems and recent suicidal thoughts and behaviours among female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, J.; Buckley, J.; Otwombe, K.; Milovanovic, M.; Gray, G.E.; Jewkes, R. Depression and Post Traumatic Stress amongst female sex workers in Soweto, South Africa: A cross-sectional, respondent driven sample. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poliah, V.; Paruk, S. Depression, anxiety symptoms and substance use amongst sex workers attending a non-governmental organisation in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2017, 59, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.A.; Nedeva, M.; Tirado, M.M.; Jacob, M. Changing research on research evaluation: A critical literature review to revisit the agenda. Res. Eval. 2020, 29, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Toronto, C.E. Overview of the integrative review. In A Step-by-Step Guide to Conducting an Integrative Review; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ouma, S.; Tumwesigye, N.M.; Ndejjo, R.; Abbo, C. Prevalence and factors associated with major depression among female sex workers in post-conflict Gulu district: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, S.A.; Lancaster, K.E.; Lungu, T.; Mmodzi, P.; Hosseinipour, M.C.; Pence, B.W.; Gaynes, B.N.; Hoffman, I.F.; Miller, W.C. Prevalence and correlates of probable depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among female sex workers in Lilongwe, Malawi. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2018, 16, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Romo, L.; Sanmartín, F.J.; Velasco, J. Invisible and stigmatized: A systematic review of mental health and risk factors among sex workers. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2023, 148, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockton, M.A.; Pence, B.W.; Mbote, D.; Oga, E.A.; Kraemer, J.; Kimani, J.; Njuguna, S.; Maselko, J.; Nyblade, L. Associations among experienced and internalized stigma, social support, and depression among male and female sex workers in Kenya. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, R.; Mo, P.K.; Ma, T.; Liu, Y.; Lau, J.T. Impact of minority stress and poor mental health on sexual risk behaviors among transgender women sex workers in Shenyang, China. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 1790–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, A.; Oliveira, A. Exploratory study on the prevalence of suicidal behavior, mental health, and social support in female street sex workers in Porto, Portugal. Health Care Women Int. 2017, 38, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabunya, P.; Byansi, W.; Damulira, C.; Bahar, O.S.; Mayo-Wilson, L.J.; Tozan, Y.; Kiyingi, J.; Nabayinda, J.; Braithwaite, R.; Witte, S.S.; et al. Predictors of depressive symptoms and post traumatic stress disorder among women engaged in commercial sex work in southern Uganda. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 298, 113817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschoeke, S.; Borbé, R.; Steinert, T.; Bichescu-Burian, D. A systematic review of dissociation in female sex workers. J. Trauma Dissociation 2019, 20, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimiaga, M.J.; Hughto, J.M.; Klasko-Foster, L.; Jin, H.; Mayer, K.H.; Safren, S.A.; Biello, K.B. Substance use, mental health problems, and physical and sexual violence additively increase HIV risk between male sex workers and their male clients in Northeastern United States. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2021, 86, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Lau, J.T.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, T.; Gu, J.; Wang, Z. Prevalence and associated factors of sexualized drug use in sex work among transgender women sex workers in China. AIDS Care 2021, 33, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitty-Anderson, A.M.; Gbeasor-Komlanvi, F.A.; Johnson, P.; Sewu, E.K.; Dagnra, C.A.; Salou, M.; Blatome, T.J.; Jaquet, A.; Coffie, P.A.; Ekouevi, D.K. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol and tobacco use among key populations in Togo in 2017: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Lin, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y. Age group differences in HIV risk and mental health problems among female sex workers in Southwest China. AIDS Care 2014, 26, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, C.E.; Witte, S.S.; Pala, A.N.; Tsai, L.C.; Wainberg, M.; Aira, T. The impact of violence, perceived stigma, and other work-related stressors on depressive symptoms among women engaged in sex work. Glob. Soc. Welf. 2017, 4, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M. Associations of physical and sexual health with suicide attempts among female sex workers in South Korea. Sex. Disabil. 2013, 31, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oermann, M.H.; Knafl, K.A. Strategies for completing a successful integrative review. Nurse Author Ed. 2021, 31, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopia, H.; Latvala, E.; Liimatainen, L. Reviewing the methodology of an integrative review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 30, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, I. Qualitative research with a focus on qualitative data analysis. Int. J. Sales Retail. Mark. 2015, 4, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ulibarri, M.D.; Hiller, S.P.; Lozada, R.; Rangel, M.G.; Stockman, J.K.; Silverman, J.G.; Ojeda, V.D. Prevalence and characteristics of abuse experiences and depression symptoms among injection drug-using female sex workers in Mexico. J. Environ. Public Health 2013, 2013, 631479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasami, M.; Zhu, H.; Dewan, M. Poverty, psychological distress, and suicidality among gay men and transgender women sex workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Phuket, Thailand. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2023, 20, 1203–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, G.L. Allen Furr, and Aylur Kailasom Srikrishnan. An assessment of the mental health of street-based sex workers in Chennai, India. J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 2009, 25, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, D.A.; Harling, G.; Muya, A.; Ortblad, K.F.; Mashasi, I.; Dambach, P.; Ulenga, N.; Mboggo, E.; Oldenburg, C.E.; Bärnighausen, T.W.; et al. Structural, interpersonal, psychosocial, and behavioral risk fac-tors for HIV acquisition among female bar workers in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS Care 2019, 31, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghose, T.; Chowdhury, A.; Solomon, P.; Ali, S. Depression and anxiety among HIV-positive sex workers in Kolkata, India: Testing and modifying the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale. Int. Soc. Work 2015, 58, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiyan, K.; Chandrasekhar, H.; Madhusudhan, S. Psychological morbidity among female commercial sex workers with alcohol and drug abuse. Indian J. Psychiatry 2012, 54, 349–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, S.S.; Batsukh, A.; Chang, M. Sexual risk behaviors, alco-hol abuse, and intimate partner violence among sex workers in Mongolia: Implications for HIV prevention intervention development. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2010, 38, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cange, C.W.; Wirtz, A.L.; Ky-Zerbo, O.; Lougue, M.; Kouanda, S.; Baral, S. Effects of traumatic events on sex workers’ mental health and suicide inten-tions in Burkina Faso: A trauma-informed approach. Sex. Health 2019, 16, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Lau, J.T.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Gao, Q.; Feng, X.; Bai, Y.; Hao, C.; Hao, Y. Socio-ecological factors associated with depression, suicidal ide-ation and suicidal attempt among female injection drug users who are sex workers in China. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 144, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, S.T.; Flaherty, B.P.; Deya, R.; Masese, L.; Ngina, J.; McClelland, R.S.; Simoni, J.; Graham, S.M. Patterns of gender-based violence and associations with mental health and HIV risk behavior among female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya: A latent class analysis. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 3273–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semple, S.J.; Pines, H.A.; Vera, A.H.; Pitpitan, E.V.; Martinez, G.; Rangel, M.G.; Strathdee, S.A.; Patterson, T.L. Maternal role strain and depressive symptoms among female sex workers in Mexico: The moderating role of sex work venue. Women Health 2020, 60, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- morbidity among female commer-cial sex workers. Indian J. Psychiatry 2017, 59, 465–470.

- Devóglio, L.L.; Corrente, J.E.; Borgato, M.H.; De Godoy, I. Smoking among female sex workers: Prevalence and associated variables. J. Bra-Sileiro Pneumol. 2017, 43, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Forteza, C.; Rodríguez, E.M.; de Iturbe, P.F.; Vega, L.; Tapia, A.J. Social correlates of depression and suicide risk in sexual workers from Hidalgo, Mexico. Salud Ment. 2014, 37, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ortblad, K.F.; Musoke, D.K.; Chanda, M.M.; Ngabirano, T.; Velloza, J.; Haberer, J.E.; McConnell, M.; Oldenburg, C.E.; Bärnighausen, T. Knowledge of HIV status is associated with a decrease in the severity of depressive symptoms among female sex workers in Uganda and Zambia. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2020, 83, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, T.R.; Williamson, C.; Ventura, L.A.; Hairston, T.R.; La Tasha, C.O.; Laux, J.M.; Moe, J.L.; Dupuy, P.J.; Benjamin, B.J.; Lambert, E.G.; et al. Offenders who are mothers with and without experience in prostitution: Differences in historical trauma, current stressors, and physical and mental health differences. Women’s Health Issues 2012, 22, e195–e200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deering, K.N.; Amin, A.; Shoveller, J.; Nesbitt, A.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Duff, P.; Argento, E.; Shannon, K. A systematic review of the correlates of violence against sex workers. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e42–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, R. Street level prostitution: A systematic literature review. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 36, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remdingpuii, M. Perceived Social Support, Stigma and Mental Health of Female Sex Workers in Aizawl City. Ph.D. Thesis, Mizoram University, Aizawl, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Akinnawo, E.O. Mental health implications of the commercial sex industry in Nigeria. Health Transit. Rev. 1995, 5, 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Alschech, J. Predictors of Violence, Traumatic Stress, and Burnout in Sex Work; University of Toronto (Canada): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Roxburgh, A.; Degenhardt, L.; Copeland, J. Posttraumatic stress disorder among female street-based sex workers in the greater Sydney area, Australia. BMC Psychiatry 2006, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, C.; Chhoun, P.; Tuot, S.; Pal, K.; Chhim, K.; Yi, S. HIV risk and psychological distress among female entertainment workers in Cambo-dia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2015, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhead, R.; Elmes, J.; Otobo, E.; Nhongo, K.; Takaruza, A.; White, P.J.; Nyamukapa, C.A.; Gregson, S. Do female sex workers have lower uptake of HIV treatment services than non-sex workers? A cross-sectional study from east Zimbabwe. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K.E.; MacLean, S.A.; Lungu, T.; Mmodzi, P.; Hosseinipour, M.C.; Hershow, R.B.; Powers, K.A.; Pence, B.W.; Hoffman, I.F.; Miller, W.C.; et al. Socioecological factors related to hazardous alcohol use among female sex workers in Lilongwe, Malawi: A mixed methods study. Subst. Use Misuse 2018, 53, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, I.; Acree, M.; O’mahony, F.; McCabe, J.; Kenny, J.; Twyford, J.; Quigley, K.; McGlanaghy, E. Male street prostitution in Dublin: A psychological analysis. J. Homosex. 2011, 58, 998–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, B.O.; Grosso, A.; Adams, D.; Ketende, S.; Sithole, B.; Mabuza, X.S.; Mavimbela, M.J.; Baral, S. The prevalence and correlates of physical and sexual violence affecting female sex workers in Swaziland. J. Inter-Pers. Violence 2018, 33, 2745–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, A.L.; Ketende, S.C.; Stahlman, S.; Ky-Zerbo, O.; Ouedraogo, H.G.; Kouanda, S.; Samadoulougou, C.; Lougue, M.; Tchalla, J.; Anato, S.; et al. Development and reliabil-ity of metrics to characterize types and sources of stigma among men who have sex with men and female sex workers in Togo and Burkina Faso. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joulaei, H.; Zarei, N.; Khorsandian, M.; Keshavarzian, A. Legalization, Decriminalization or Criminalization; Could We Introduce a Global Prescription for Prostitution (Sex Work)? Int. J. High Risk Behav. Addict. 2021, 10, e106741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Koehl, M.; Rivas-Koehl, D.; McNeil Smith, S. The temporal intersectional minority stress model: Reimagining minority stress theory. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2023, 15, 706–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porritt, K.; Gomersall, J.; Lockwood, C. JBI’s systematic reviews: Study selection and critical appraisal. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tod, D.; Booth, A.; Smith, B. Critical appraisal. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 15, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Published Studies | Research Methodology | Population (n) | Country (Location) | Age-Range (Years) | Outcomes | Research Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puri et al., 2017 [1]. | Quantitative | 692 | British Columbia | ≥18 | Depression, Anxiety. | Moderate (5) |

| Zehnder et al., 2019 [2]. | Qualitative | 60 | Switzerland | 18 or above | Mental health service use was defined as the use of psychiatric medication, psychotherapy, or substance use services for at least one month during the past six months. | Low quality (3) |

| Ranjbar et al., 2019 [4]. | Quantitative | 48 | Iran | 18–45 | High burden of depression. | Strong (7) |

| Millan-Alanis et al., 2021 [5]. | Systematic review and meta-Analysis | 55 | Systematic review | >18 | High prevalence of suicidality, depression, and PTSD among FSWs. | Strong (8) |

| Kanayama et al., 2022 [6]. | Quantitative | 403 | Myanmar | 16–48 | Violence perpetrated by clients and threats of violence from partners induces severe symptoms of anxiety and depression. | Moderate (5) |

| Beksinska et al., 2022 [7]. | Quantitative | 1039 | Kenya | 18–45 | High levels of persistent suicidal behaviors among FSWs. | Strong (10) |

| Panneh et al., 2022 [8]. | Qualitative | 40 | Kenya | 18–45 | The majority of participants understood ‘mental health’ as ‘insanity’, ‘stress’, ‘depression’, and ‘suicide’. | Strong (7) |

| Beattie et al., 2020 [9]. | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 68 | Systematic review | 11–64 | A meta-analysis found significant associations between violence experience and depression, violence experience and recent suicidal behavior, alcohol use and recent suicidal behavior, illicit drug use and depression, depression and inconsistent condom use with clients, and depression and HIV infection. | Strong (10) |

| Rossler et al., 2010 [10]. | Qualitative | 2165 | Cameroon | 18 or over | Mediation analysis, both sexual violence and severe depression remained significant predictors of condomless sex. | Moderate (6) |

| Hengartner et al., 2015 [11]. | Quantitative | 193 | Switzerland | 18–63 | We found high rates of mental disorders among female sex workers. Additionally, 1-year prevalence rates were high, which points to the immediate burden associated with sex work. | Strong (7) |

| Sagtani et al., 2013 [12]. | Quantitative | 88 | Netherlands | 20–70 | Female prostitution has included samples with a high prevalence of substance abuse, violence, and human trafficking. | Strong (7) |

| Hong et al., 2013 [15]. | Cross-section study | 1986 | Southern India | Above 30 | Almost two-fifths of FSWs (39%) reported significant depression. | Strong (8) |

| Estrada-Tranck, 2023 [16]. | Cross-sectional | 1022 | China | >18 | Partner violence was strongly associated with each of the five measures of psychosocial distress, even after controlling for potential confounders. | Moderate (5) |

| Zhang et al., 2014 [17]. | Quantitative | 1022 | China | >18 | F–G relationship is an independent predictor of the mental health of FSW over and above potential confounders, including partner violence and substance use. | Strong (7) |

| Duff et al., 2017 [18]. | Qualitative | 800 | Canada | 14 and older | In multivariable analysis, poor working conditions were associated with increased work stress and included workplace physical/sexual violence. | Moderate (5) |

| Jewkes et al., 2021 [20]. | Cross-sectional | 18 or older | South Africa | 30 | FSWs’ poor mental health risk was often mediated by their work location and vulnerability to violence, substance abuse and stigma. | Strong (8) |

| Beksinska et al., 2021 [21]. | Cross-sectional qualitative and quantitative | 1000 | Kenya | 18–45 | Qualitative interviews found that childhood neglect and violence were drivers of entry into sex work and alcohol use and that alcohol and cannabis helped women cope with sex work. | Strong (8) |

| Coetzee et al., 2018 [22]. | Cross-sectional | 508 | South Africa | >12 | Findings highlight the sizable burden of treatable mental health conditions among FSWs in Soweto. This was driven by multiple exposures to violence, sex work-related discrimination and overall moderate levels of self-esteem masking defense mechanisms. | Moderate (4) |

| Poliah and Paruk, 2017 [23] | Quantitative | 624 | Mexico | Older 18 | FSW-IDUs identified drug use as a method of coping with the trauma they experienced from abuse. | Moderate (5) |

| Ouma et al., 2021 [27]. | Cross-sectional | 300 | Uganda | More than 20 | The study underscores the high magnitude of MD driven by multiple sex work-related factors like the presence of a psychosocial stressor, living with HIV, experiencing verbal abuse from clients, and older age. | Strong (7) |

| MacLean et al., 2018 [28]. | Cross-sectional | 200 | Malawi | 20–24 | High prevalence of depression, PTSD, and suicide. | Moderate (4) |

| Martín-Romo et al., 2023 [29]. | Systematic review | 30 | Systematic review | 18–71 | Mental health problems were prevalent among sex workers. Depression was the most common mental health problem; however, other psychological problems were also high, including anxiety, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation. | Strong (7) |

| Stockton et al., 2020 [30]. | Cross-sectional | 729 | Kenya | Over 18 | Increasing levels of experienced stigma were associated with an increased predicted prevalence of depression. | Moderate (5) |

| She et al., 2021 [31]. | Cross-sectional | 204 | China | Over 18 | The present study identified a high prevalence of co-occurring psychosocial health conditions and sexual risk behaviors. | Strong (8) |

| Teixeira et al., 2017 [32]. | Quantitative | 52 | Portugal | 18–63 | Both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts are prevalent in female street sex workers. | Moderate (6) |

| Nabunya et al., 2021 [33]. | Longitudinal randomized clinical trial | 542 | Uganda | 18–55 | Women engaged in commercial sex work are at a higher risk of HIV and poor mental health outcomes. Sex work stigma and financial distress elevate levels of depressive symptoms and PTSD over and above an individual’s HIV status. | Strong (9) |

| Tschoeke et al., 2019 [34]. | Systematic Review | 554 | Systematic review | Over 18 | Most study participants were street FSWs characterized by high rates of revictimization, a history of childhood sexual abuse, and trauma-related and substance use disorders. | Moderate (4) |

| Mimiaga et al., 2021 [35]. | Quantitative | 100 | USA | 18 or older | Street-based MSWs are a vulnerable group for experiencing psychosocial problems and engaging in HIV sexual risk with male clients. | Moderate (4) |

| Fan et al., 2021 [36] | Cross-sectional | 220 | China | 18–30 | Poor mental health status (depressive and anxiety symptoms) is associated with a higher likelihood of SDU in sex work. | Moderate (5) |

| Bitty-Anderson et al., 2019 [37]. | Cross-sectional | 2115 | Ghana | 18 | The prevalence of alcohol consumption, hazardous/harmful consumption, and binge drinking was 64.8%, 38.4%, and 45.5%, respectively. | Moderate (4) |

| Su et al., 2014 [38]. | Qualitative | 1022 | China | 21–34 | Mental health problems were more prevalent among older and younger FSWs than among medium-aged FSWs. | Strong (7) |

| Carlson et al., 2017 [39]. | Quantitative | 222 | Mongolia | >18 | A linear regression analysis indicated that significant risk factors for depressive symptoms included paying partner sexual violence, perceived occupational stigma, less social support, and higher harmful alcohol use. | Strong (9) |

| Jung 2013 [40]. | Quantitative | 1083 | South Korea | 18 or older | A higher suicide attempt likelihood was associated with poor sexual and physical health, but there was no significant association with the number of customers per week. | Moderate (6) |

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Winter, M.L.; Olivia, S.G. Life Intricacies of Sex Workers: An Integrative Review on the Psychiatric Challenges Faced by Sex Workers. Psychiatry Int. 2024, 5, 395-411. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint5030027

Winter ML, Olivia SG. Life Intricacies of Sex Workers: An Integrative Review on the Psychiatric Challenges Faced by Sex Workers. Psychiatry International. 2024; 5(3):395-411. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint5030027

Chicago/Turabian StyleWinter, Mokhwelepa Leshata, and Sumbane Gsakani Olivia. 2024. "Life Intricacies of Sex Workers: An Integrative Review on the Psychiatric Challenges Faced by Sex Workers" Psychiatry International 5, no. 3: 395-411. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint5030027

APA StyleWinter, M. L., & Olivia, S. G. (2024). Life Intricacies of Sex Workers: An Integrative Review on the Psychiatric Challenges Faced by Sex Workers. Psychiatry International, 5(3), 395-411. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint5030027