1. Introduction

We are currently living in a new digital age in which the internet is the most accessible and utilized means of communication, especially for the younger generations, where they can enjoy greater ease of access through digital platforms that contain chats, games, photo posting, etc. [

1]. Kimberly Young and Mark Griffiths were the first authors to explore the impact that new technologies would have on society, eventually developing the concept of internet addiction [

2,

3].

According to [

4], internet addiction encompasses a variety of online behaviors that are considered pathological when individuals are not able to regulate them, such as a compulsion to shop or play online games (in which money is invested), excessive surfing of web pages, online video game addiction, and cybersex/pornography. Online addiction, considered by many authors to be problematic internet use, has severe implications for both physical health (e.g., body posture problems and tendonitis) and mental health (e.g., depression and social isolation) and the development of young people [

5,

6]. Concerning internet addiction according to gender, ref. [

7] states that girls are more likely to have higher levels of online addiction. However, ref. [

8] establishes some differences between girls and boys, stating that boys have a higher dependence on online games and girls have a higher dependence on social networks. According to [

9], the prevalence of online addiction in general is higher in boys, but when it comes to social networks, this prevalence is higher in girls. As for age, ref. [

10] states that young people between 15 and 16 are most dependent on the internet.

Having said that, ref. [

4] developed an instrument entitled the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) consisting of a set of questions such as “Do you feel worried about the Internet?”; “Do you stay online longer than you initially intended?”; and “Do you feel restless, depressed or irritable when you try to cut down or stop using the Internet?”, among others, with the purpose of assessing internet addiction. According to the criteria in [

4], subjects answering affirmatively to five or more of these questions would be considered dependent users. For [

2,

3], internet addiction involves not only spending many hours online but also compromising the normal functioning of the subject in society, namely through uncontrolled and unconscious interactions. However, it should be noted that moderate and controlled internet use does not present significant risks for individuals since it allows for remote socialization and the creation or strengthening of new relationships [

2,

3,

11].

Research on online addiction has grown internationally and nationally in recent years. Previous studies have issued warnings about the incidence of cases of young people at risk of online addiction, which implies the need for continuous and deeper study of the explanatory variables of this phenomenon [

12].

A study conducted in a partnership between the APAV (Portuguese Association for Victim Support) and Geração Cordão to assess online risk behaviors and the impact of internet use on mental health in a sample of young Portuguese through the data presented in descriptive and inferential statistics indicated which characteristics are associated with a risk profile of technology and internet use in this sample. The most prevalent characteristics of young people who present an online or smartphone addiction are presented in

Table 1 [

13].

Some of these typical characteristics of young people with online addictions (

Table 1) are common to the findings of the study by [

14].

In addition to the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) developed by [

15], several instruments allow us to study internet addiction (

Table 2).

However, in a literature review by [

22], the most used instrument in studies on this subject is the Internet Addiction Test, with 1096 citations. It is also the most used instrument in different countries. Consulting Scopus reveals that the article containing this instrument has 2911 citations.

Some of the countries who have translated, adapted, or used this instrument are listed in

Table 3.

Therefore, the existence of an instrument to screen for internet addiction has become increasingly relevant in clinical practice so as to prevent online risk behaviors and the impact of internet use on mental health.

Having said this, the aim of this study was to adapt and evaluate a shortened version of the IAT (Internet Addiction Test) scale completed by young people aged 12 years and older in relation to their online behaviors and risk of online addiction. The psychometric qualities of the reduced version (Screening IAT—young people) are presented in order to validate the use of this version in the early detection of online addiction. The following research hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 1. The reduced version of the IAT scale has good psychometric qualities.

3. Results

3.1. Validity, Reliability, and Sensitivity of the Instrument

To perform the factorial analysis, the total sample was randomly divided into three samples. In the first sample, 600 participants were extracted; in the second, 1200 participants were extracted; and in the third, 1221 participants were extracted.

An exploratory factor analysis was carried out using the initial sample. According to the first exploratory factor analysis, the scale was formed by a single factor (uni-dimensional) with a KMO of 0.86, which was good [

46] (Sharma, 1996), and the results of Bartlett’s test of sphericity were significant at

p < 0.001, indicating that the data were from a multivariate normal population [

47] (Pestana & Gageiro, 2003). The factor structure of this scale was based on a factor that explained 51% of the total variability of the scale. All items had factor weights above 0.50 (

Table 5). As for internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83.

In the subsequent confirmatory factor analysis carried out with a sample of 1200 participants, the obtained adjustment indices proved to be adequate (χ2/gl = 2.93; GFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.040; SRMR = 0.029). The internal consistency presented a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84. It also showed good construct reliability with a value of 0.85 and convergent validity with a value of 0.45.

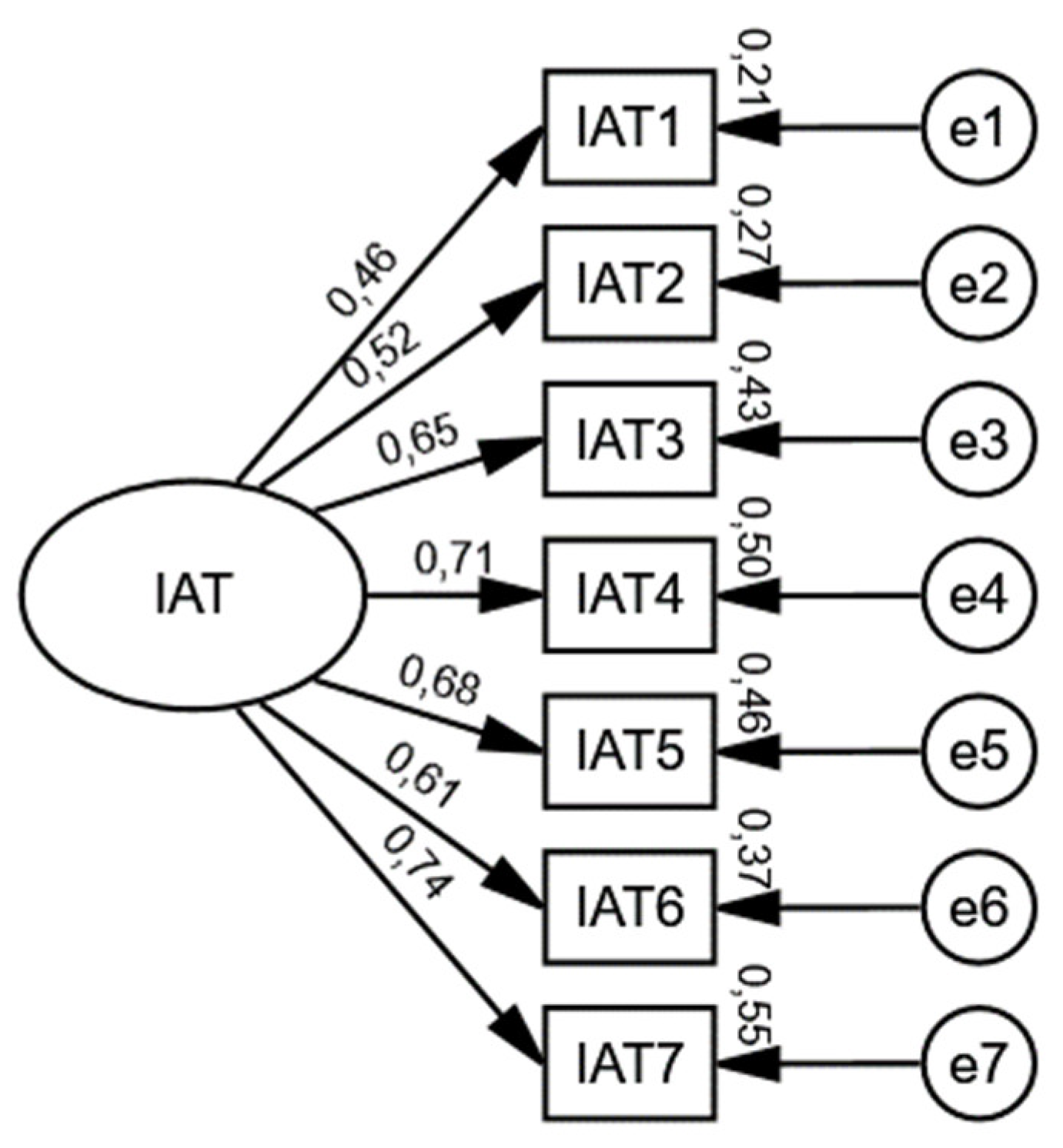

Figure 1 shows the factorial weight as well as the individual reliability of each of the items of the sample with 1200 participants.

Concomitantly, in the confirmatory factor analysis carried out with a sample of 1221 participants, the obtained adjustment indices were adequate (χ2/gl = 2.97; GFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.040; SRMR = 0.025). It also showed good construct reliability with a value of 0.82 and convergent validity with a value of 0.40.

Figure 2 presents the factorial weight and the individual reliability of each item of the sample with 1221 participants.

Next, the invariance of the Internet Addiction Test model in boys and girls was tested and assessed by comparing the free model (with factor weights and variances/covariances of the free factors) with the construct model in which the factor weights and variances/covariances of both groups were fixed. The significance of both models was measured using the chi-square test described by [

48]. The restricted model, with factorial weights and variances/covariances fixed between the two groups, did not show a significantly worse fit than the model with free parameters (∆χ 2λ(6) = 18.12;

p = 0.229), which indicated the invariance of the measurement model of the Internet Addiction Test between boys and girls. We also found that the intercepts were invariant (∆χ 2i(7) = 10.768;

p = 0.149), which indicated that we were looking at a model with strong invariance.

The scale’s internal consistency was tested among the 3021 participants, obtaining a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83.

Concerning item sensitivity, it was found that none of the items had a median close to one of the extremes, all items had responses at all points, and their absolute values of skewness and kurtosis were below two and seven, respectively (

Table 6), which indicated that they did not grossly violate normality [

49]. As far as the scale was concerned, it did not grossly violate normality since its absolute skewness and kurtosis values were below two and seven, respectively [

49].

3.2. Prevalence of Internet Addiction in the Sample

According to [

15], the IAT instrument, composed of 20 items, distinguished three types of users according to their different levels of internet use. To this end, they created three cut-off points: 20–39 = average user; 40–69 = a person who has frequent problems due to their internet use; and 70–100 = internet addicts. In [

23], the authors used the same cut-off points in their adaptation to the Portuguese population. However, as the reduced version proposed in this study is composed of only seven items, the proposed cut-off points are 0–11 = low risk of addiction; 12–19 = moderate risk of addiction; and 20–35 = high risk of addiction.

According to the proposed cut-off criteria, 1710 (56.6%) of the participants in this study showed a low risk of internet addiction, 1051 (34.8%) showed a moderate risk of internet addiction, and 260 (8.6%) showed a high risk of internet addiction.

3.3. Effects of Sociodemographic Variables on Internet Addiction

Finally, the effects of sociodemographic variables on internet addiction were tested. A Student’s t-test for independent samples was used for gender. Female participants were found to have higher levels of internet addiction than male participants (

Table 7). However, these differences were not statistically significant (t (3019) = 0.90;

p = 0.364; d = 0.03).

A one-way parametric ANOVA was used for the level of education. The participants with junior high school education revealed higher levels of internet addiction, followed by those with high school education and, finally, those attending college (

Table 7). Nevertheless, these differences were not statistically significant (F (3, 3018) = 0.51;

p = 0.600).

The association between age and internet addiction was also tested using Pearson’s correlations.

The results show that age was negatively and significantly associated with internet addiction (r = −0.036;

p = 0.046), which means that younger participants showed greater internet addiction (

Table 8).

We then tested whether sociodemographic variables were independent of internet addiction. To this end, the chi-squared test of independence was used.

The percentage of female participants with a low risk of internet addiction was similar to the percentage for males. This was also true for a moderate risk of internet addiction. However, the percentage of participants with a high risk of internet addiction was higher in female participants when compared with male participants (

Table 9). The chi-squared test (χ

2 (2) = 1.18;

p = 0.555; V = 0.02) suggested that the two variables were independent.

When testing the independence of the risk of internet addiction and the level of education, it was found that these variables were not independent (χ

2 (4) = 16.07;

p = 0.003; V = 0.07). The youngsters attending university had a higher percentage with a low risk of internet addiction. However, they had the lowest percentage with a moderate or high risk of internet addiction. The participants in secondary school had a higher percentage with a moderate risk of internet addiction. As for the high risk of internet addiction, the participants in primary schools were revealed to have a higher percentage (

Table 10).

4. Discussion

The main objective of this study was to validate a reduced version of the instrument developed by [

45] and adapted for the Portuguese population by [

23], consisting of 20 items. This instrument measures internet addiction. The version proposed in this article is a reduced version composed of seven items, which will be applied to young people attending primary schools, secondary schools, and higher education. We chose the items that are consistent with the general criteria of internet addiction (e.g., tolerance, mood change, and interpersonal conflict) and presented higher factor weights in both the version adapted to the Portuguese population and subsequent studies. This selection was reinforced by an assessment performed by one of the researchers of this study in her clinical practice, who detected that these items are the most relevant.

As previously mentioned, the sample of this study was composed of 3021 participants. For scale validation, the sample was divided into three parts. An exploratory factor analysis was performed with 600 participants and obtained a good KMO value [

46]. More than 0.50 of the total variance was explained, and all items had factor weights greater than 0.50.

The other parts into which the sample was divided consisted of 1200 and 1221 participants. Two one-factor confirmatory factor analyses were carried out with these two samples. The obtained adjustment indices are all adequate [

42]. Comparing the CFA results obtained in this study with those of the study carried out by [

27], it can be seen that the adjustment indices obtained in this study are better. It should be noted that the sample size in [

27] was much smaller than the sample in this study (n = 463), and the average age of the participants was also higher. On the other hand, the adjustment indices are identical to those of the study carried out by [

38]. They show good construct reliability, although their convergent validity is slightly below 0.50. However, when the Cronbach’s alpha value is above 0.70, AVE values greater than 0.40 are acceptable, indicating good convergent validity [

44].

Finally, we randomly divided the whole sample into two parts to perform a gender invariance analysis, which confirmed that we were studying a model with strong invariance. These results align with those obtained by [

38], who confirmed invariance according to the participant’s gender.

Regarding the internal consistency, the scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83, which can be considered good [

50]. All items show good sensitivity, which indicates that they can discriminate subjects. The Cronbach’s alpha value obtained in this study is higher than that of [

27], indicating better internal consistency.

The effects of sociodemographic variables on internet addiction showed us that female participants had more internet addiction than male participants, which may have been related to the social network consumption profile associated with the female gender. This profile is more normalized, as it is a source of contact with others and socialization. These results align with the findings of some authors, such as [

7], who found that girls are more likely to experience online addiction than boys. However, boys may experience more problems with online games, while girls prefer social networks [

8].

Concerning the level of education, the participants at primary schools had higher levels of internet addiction. This result is related to difficulties in the self-control of behavior and emotions during development. Throughout a school career and its different demands and challenges, an increasing learning curve of self-control of behavior and emotions can be expected.

Concerning age, there was a negative and significant correlation between age and internet addiction. These results are in line with a study carried out by [

10], who tells us that they found the highest internet addiction among young people between the ages of 15 and 16 (our sample was composed of participants between the ages of 12 and 25).

The main limitations of this study are the fact that it used a self-report instrument and that we were dealing with participants over 12 years of age since in this area of internet addiction, from a clinical point of view, young people tend to perceive contact and the acceptable use of technology without assessing the impact on their daily functioning (e.g., impact on sleep routines, eating, and studying). It should be noted that young people at this age are often unaware of their dependence on the internet.

Another limitation of this study is the small number of sociodemographic questions included in the questionnaire. As in previous studies, among other questions, it would have been interesting to ask about the frequency and duration of time spent on the internet.

Another suggestion is to recommend that parents read the “Practical guide to the healthy use of technology” developed by the project of Geração Cordão [

51]. This instrument, since it has few items, could be beneficial in the early diagnosis of internet addiction in young adolescents.