Clinical Trial Studies of Antipsychotics during Symptomatic Presentations of Agitation and/or Psychosis in Alzheimer’s Dementia: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Questions

2.1. Methods

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|

|

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Comparator

2.5. Outcomes

| Primary Outcomes | Secondary Outcomes |

|

|

2.6. Search Strategy

2.7. Information Sources

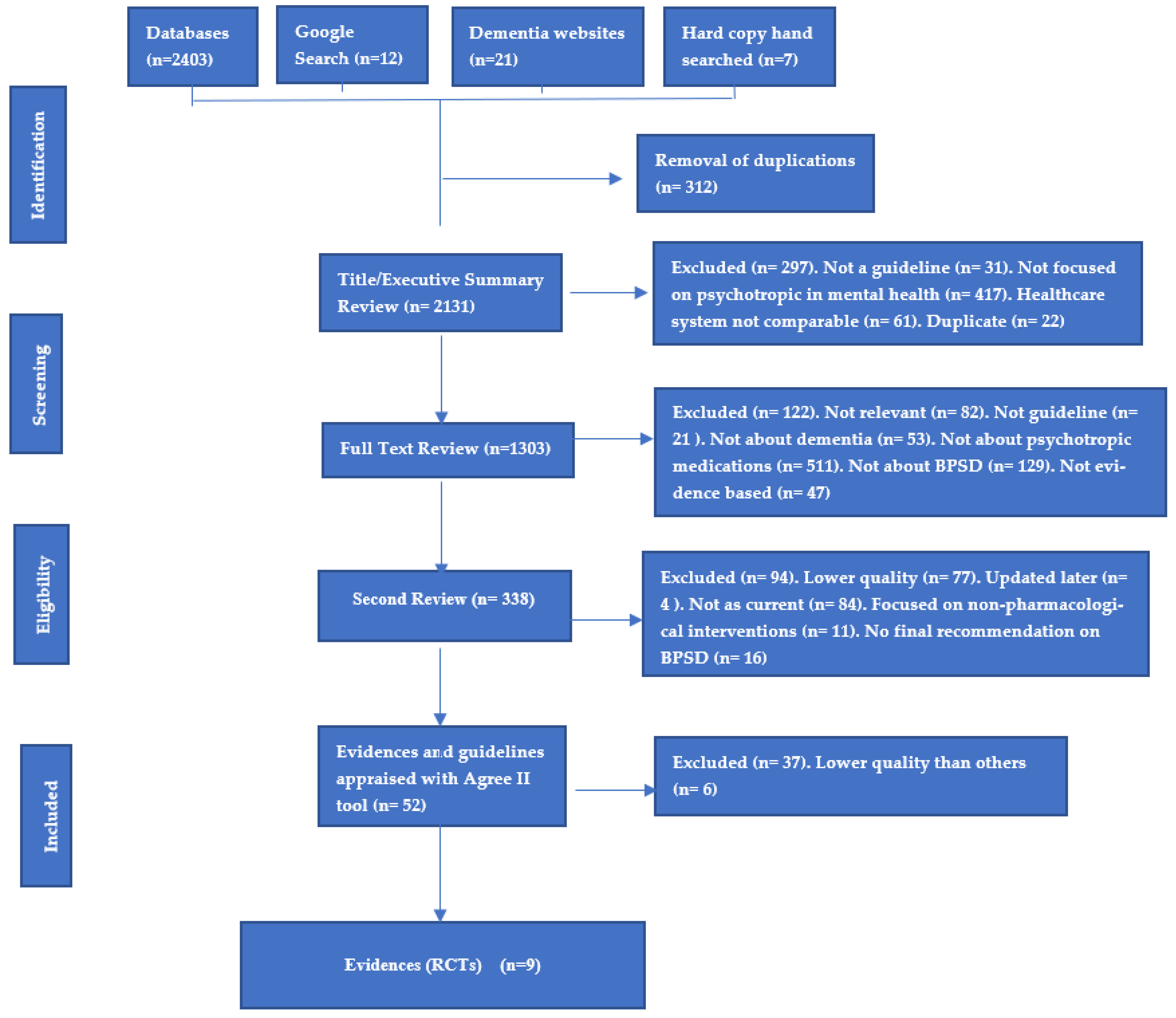

2.8. Study Selection

2.9. Assessment of Methodological Quality

2.10. Data Extraction

2.11. Assessing Certainty in the Findings

3. Results

3.1. Methodological Quality

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Review Findings

3.4. Antipsychotics

3.5. Findings with Quetiapine

3.6. Findings with Haloperidol

3.7. Findings with Olanzapine

3.8. Findings with Brexpiprazole

3.9. Findings of Pimavanserine

3.10. Findings with Aripiprazole

3.11. Findings with Risperidone

4. Discussion

Quality of This Systematic Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Strategy

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Population | Dementia (any type) Aged from 18 to older Cognitive disorders, memory problems, cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy bodies dementia, vascular dementia, Parkinson’s disease with dementia | Any other psychiatry or mental health disorders |

| Intervention | Pharmacological interventions Any Atypical antipsychotics | Treatments not related to psychotropics Non-pharmacological interventions |

| Comparator | Pharmacology vs. non-pharmacology or vs. placebo Pharmacology vs. usual care | Nil |

| Outcomes | Patient’s health outcome Morbidity Mortality Quality of life Efficacy Safely Adverse effects | Outcomes among healthcare or caregivers or health professional staff |

| Settings | Community sectors Aged Care Facilities and Nursing Homes Hospitals Out-patient clinics | Nil |

| Study Designs | Randomized Controlled trials (RCTs), Blinded or double blinded -Placebo Controlled or compared with other psychotropics | Case reports Case studies Opinion reports Commentaries Conference abstracts Thesis/dissertations Letters (with no data) |

References

- Qasim, H.; Simpson, M.; Guisard, Y.; de Courten, B. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Studies on the Adverse Effects of Medications in Australian Aged care Facilities: A Scoping Review. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, H.S.; Simpson, M.D. A Narrative Review of Studies Comparing Efficacy and Safety of Citalopram with Atypical Antipsychotics for Agitation in Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD). Pharmacy 2022, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, T.; Cavanagh, J.; Pariona-Cabrera, P.; Halvorsen, B.; Shao, J.; Stanton, P. Worrying about Being Hit at Work. Report of the ANMF’s 10 Point Plan in Private Aged Care Facilities across the Sate of Victoria. Available online: https://www.anmfvic.asn.au/~/media/Files/ANMF/OHS/RMIT-ReportANMF10ppAgedCare-FA.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Magierski, R.; Sobow, T.; Schwertner, E.; Religa, D. Pharmacotherapy of Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia: State of the Art and Future Progress. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrarini, C.; Russo, M.; Dono, F.; Barbone, F.; Rispoli, M.G.; Ferri, L.; Di Pietro, M.; Digiovanni, A.; Ajdinaj, P.; Speranza, R.; et al. Agitation and Dementia: Prevention and Treatment Strategies in Acute and Chronic Conditions. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 644317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigbogun, M.S.; Cloutier, M.; Gauthier-Loiselle, M.; Guerin, A.; Ladouceur, M.; Baker, R.A.; Grundman, M.; Duffy, R.A.; Hartry, A.; Gwin, K.; et al. Real-World Treatment Patterns and Characteristics Among Patients with Agitation and Dementia in the United States: Findings from a Large, Observational, Retrospective Chart Review. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 77, 1181–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, D.P.; Adunuri, N.; Gill, S.S.; Gruneir, A.; Herrmann, N.; Rochon, P. Antidepressants for agitation and psychosis in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 2, CD008191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, P.; Jones, R.; Gabe-Walters, M.; Qasim, H.; Jordan, S. Strategizing to Identify Preventable Adverse Drug Reactions in Rural and Regional Aging Populations of Australia. In Proceedings of the 52nd Edition of the Australian Association of Gerontology Conference, Sydney, Australia, 5–8 November 2019; Available online: http://www.aag.asn.au/national-conference/2019-conference-program-abstracts-presentations (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Lee, K.S.; Kim, S.H.; Hwang, H.J. Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia and Antipsychotic Drug Use in the Elderly with Dementia in Korean Long-Term Care Facilities. Drugs Real. World Outcomes 2015, 2, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.Y.; Yang, D.W.; Kim, J.S.; Cho, A.H. Safety and Efficacy of Anti-dementia Agents in the Extremely Elderly Patients with Dementia. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2018, 33, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnelli, A.; Ott, S.; Mayer, H.; Zeller, A. Factors associated with aggressive behaviour in persons with cognitive impairments using home care services: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudev, A.; Shariff, S.Z.; Liu, K.; Burhan, A.M.; Herrmann, N.; Leonard, S.; Mamdani, M. Trends in Psychotropic Dispensing Among Older Adults with Dementia Living in Long-Term Care Facilities: 2004–2013. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.M. New hope for Alzheimer’s dementia as prospects for disease modification fade: Symptomatic treatments for agitation and psychosis. CNS Spectr. 2018, 23, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.M. Beyond the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia to three neural networks of psychosis: Dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate. CNS Spectr. 2018, 23, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariot, P.N.; Schneider, L.; Katz, I.R.; Mintzer, J.E.; Street, J.; Copenhaver, M.; Williams-Hughes, C. Quetiapine treatment of psychosis associated with dementia: A double- blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultzer, D.L.; Gray, K.F.; Gunay, I.; Wheatley, M.V.; Mahler, M.E. Does behavioral improvement with haloperidol or trazodone treatment depend on psychosis or mood symptoms in patients with dementia? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 1294–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurlan, R.; Cummings, J.; Raman, R.; Thal, L. Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Group. Quetiapine for agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia and parkinsonism. Neurology 2007, 68, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossberg, G.T.; Kohegyi, E.; Mergel, V.; Josiassen, M.K.; Meulien, D.; Hobart, M.; Slomkowski, M.; Baker, R.A.; McQuade, R.D.; Cummings, J.L. Efficacy and Safety of Brexpiprazole for the Treatment of Agitation in Alzheimer’s Dementia: Two 12-Week, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trials. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodaty, H.; Ames, D.; Snowdon, J.; Woodward, M.; Kirwan, J.; Clarnette, R.; Lee, E.; Greenspan, A. Risperidone for psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease and mixed dementia: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, C.; Banister, C.; Khan, Z.; Cummings, J.; Demos, G.; Coate, B.; Youakim, J.M.; Owen, R.; Stankovic, S.; Tomkinson, E.B.; et al. Evaluation of the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of pimavanserin versus placebo in patients with Alzheimer’s disease psychosis: A phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, C.; Margallo-Lana, M.; Juszczak, E.; Douglas, S.; Swann, A.; Thomas, A.; O’Brien, J.; Everratt, A.; Sadler, S.; Maddison, C.; et al. Quetiapine and rivastigmine and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease: Randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2005, 330, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzer, J.E.; Tune, L.E.; Breder, C.D.; Swanink, R.; Marcus, R.N.; McQuade, R.D.; Forbes, A. Aripiprazole for the treatment of psychoses in institutionalized patients with Alzheimer dementia: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled assessment of three fixed doses. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 15, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streim, J.E.; Porsteinsson, A.; Breder, C.D.; Swanink, R.; Marcus, R.; McQuade, R.; Carson, W.H. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of aripiprazole for the treatment of psychosis in nursing home patients with Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 16, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultzer, D.L.; Davis, S.M.; Tariot, P.N.; Dagerman, K.S.; Lebowitz, B.D.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Rosenheck, R.A.; Hsiao, J.K.; Lieberman, J.A.; Schneider, L.S.; et al. Clinical symptom responses to atypical antipsychotic medications in Alzheimer’s disease: Phase 1 outcomes from the CATIE-AD effectiveness trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, B.G.; Mulsant, B.H.; Rosen, J.; Mazumdar, S.; Blakesley, R.E.; Houck, P.R.; Huber, K.A. A double-blind comparison of citalopram and risperidone for the treatment of behavioral and psychotic symptoms associated with dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 15, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, T.C.; Ford, B.K. What is known about dementia care recipient violence and aggression against caregivers? J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2014, 57, 460–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheu, S. Witness Gives Evidence on Violence against Staff. Australian Aging Agenda. Available online: https://www.australianageingagenda.com.au/royal-commission/witness-gives-evidence-on-violence-against-staff/ (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Joller, P.; Gupta, N.; Seitz, D.P.; Frank, C.; Gibson, M.; Gill, S.S. Approach to inappropriate sexual behaviour in people with dementia. Can. Fam. Physician 2013, 59, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, B.; Shaw, H.; Macdonald, O. Guidelines for the Management of Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD). Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust. Available online: http://www.oxfordhealthformulary.nhs.uk/docs/OHFT%20BPSD%20Guideline%20May%202019.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline on the Use of Antipsychotics to Treat Agitation or Psychosis in Patients with Dementia; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Clinical Guideline No. 21. Appropriate Prescribing of Psychotropic Medication for Non-Cognitive Symptoms in People with Dementia. Available online: https://www.lenus.ie/bitstream/handle/10147/627015/43428_0ab63bed4afb4f388b99801882e04652.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Guideline Adaptation Committee. Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for People with Dementia. Sydney. Available online: https://cdpc.sydney.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/CDPC-Dementia-Guidelines_WEB.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia: Assessment, Management and Support for People Living with Dementia and Their Carers. Guideline. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97/resources/dementia-assessment-management-and-support-for-people-living-with-dementia-and-their-carers-pdf-1837760199109 (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Masopust, J.; Protopopová, D.; Vališ, M.; Pavelek, Z.; Klímová, B. Treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementias with psychopharmaceuticals: A review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinkley, K.E.; Sturm, A.M.; Porter, K.; Nahata, M.C. Efficacy and Safety of Atypical Antipsychotics for Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia Among Community Dwelling Adults. J. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 33, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, C.; Kales, H.C.; Lyketsos, C.; Aarsland, D.; Creese, B.; Mills, R.; Williams, H.; Sweet, R.A. Psychosis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2020, 20, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RCT Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tariot et al., 2006 [16] | Y | U | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Sultzer et al., 2008 [17] | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | 9 |

| Kurlan et al., 2007 [18] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Grossberg et al., 2020 [19] | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Brodaty et al., 2005 [20] | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 12 |

| Ballard et al., 2018 [21] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 13 |

| Ballard et al., 2005 [22] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 13 |

| Mintzer et al., 2007 [23] | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

| Streim et al., 2008 [24] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Total Score | 9 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| RCT Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Q15 | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tariot et al., 2006 [16] | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 9 |

| Sultzer et al., 2008 [17] | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 12 |

| Kurlan et al., 2007 [18] | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 12 |

| Grossberg et al., 2020 [19] | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 12 |

| Brodaty et al., 2005 [20] | Y | Y | Y | U | N | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

| Ballard et al., 2018 [21] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 14 |

| Ballard et al., 2005 [22] | Y | Y | Y | U | N | N | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Mintzer et al., 2007 [23] | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 12 |

| Streim et al., 2008 [24] | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 13 |

| Total Score | 9 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 |

| Medication | Total No. of Patients | Effective Dose | Psychosis | Agitation | Indication | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quetiapine | 236 | 100 mg daily | ++ | +++ | Agitation/Psychosis | +++ |

| Haloperidol | 122 | 2 mg daily | + | +++ | Agitation | +++ |

| Olanzapine | 92 | 2.5–5 mg daily | ++/worsened psychosis/Improved suspiciousness and aggressiveness | ++ | Agitation/Psychosis | +++ |

| Brexpiprazole | 703 | 2 mg daily | + | +++ | Specific for Agitation | + |

| Pimavanserin | 181 | 17 mg twice daily/or 34 mg daily at one dose | +++ | + | Specific for psychosis | ++ |

| Aripiprazole | 743 | 10 mg < daily | +++ | ++ | Agitation/Psychosis | + |

| Risperidone | 178 | 0.5–1 mg daily | +++ | ++ | Agitation/Psychosis | ++ |

| Study | Study Design | Country/ Setting | Participants | Characteristics of Participants | Assessment Tools | Interventions | Comparators | Length of Follow-Up | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tariot et al., 2006 [16] | Double-Blinded, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial | 47 sites of home residents and aged care facilities throughout United States | Quetiapine n = 91, Haloperidol n = 94, Placebo n = 99 | >64 years old, residents in aged care facilities, diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia | Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Score (BPRS), Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGI-C), Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination (SMMSE), Multi-dimensional Observation Scale for Elderly (MOSES), and Physical Self-Maintenance Scale (PSMS). | Quetiapine group given 25 mg daily and increased by 25 mg per day for a week, then increased 25 mg every four days to a target dosage of 100 mg daily. Based on clinical responses, quetiapine can be increased to maximum 600 mg daily | Haloperidol group given 0.5 mg daily. Increased by 0.5 mg daily, then increased by 0.5 mg every four days over 14 days. Based on clinical responses, haloperidol can be increased to maximum 12 mg daily | 10 weeks (baseline and ongoing follow-up recorded on week 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10. | Quetiapine, haloperidol and placebo showed improvement in measures of psychosis. No significant difference in the medications. Inconsistent evidence of quetiapine and haloperidol in regards to improvement of agitation. Tolerability better with quetiapine compared with haloperidol. |

| Sultzer et al., 2008 [17] | Double Blinded RCT | 42 clinical sites/hospitals and out-patients clinical centers in United State | 421 enrolled patients were randomized initially to masked treatments with olanzapine n = 100, quetiapine n = 94, risperidone n = 85, and placebo n = 142. | >65 years or older, diagnosed with dementia, Alzheimer’s type, reported delusions, hallucinations, agitation or aggression for at least 4 weeks. | Psychiatric and behavioral symptoms, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Questionnaire), Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Score (BPRS), Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia, AD Cooperative Study-Clinician’s Global Impression of Change (CGIC), AD Assessment Scale- Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog) and MMSE, Activities of Daily Living Scale (ADCS-ADL), Dependence Scale, Caregiver Activity Scale, and Alzheimer’s Disease Related Quality of Life (ADRQL). | The doses were prepared in low dose to high dose as the following: olanzapine (2.5 mg or 5 mg), quetiapine (25 mg or 50 mg), risperidone (0.5 mg or 1 mg), or placebo. | Comparison between the three medications and with placebo, the comparison at 2:2:2:3 ratio. | 36 weeks. The follow-up and the assessment of week 2, week 4, week 8, week 12, week 24, and week 36 of treatment. | Olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone provided some clinical symptoms improvement. The three agents provided efficacy for particular symptoms such as anger, aggression, and paranoid ideas. However, functional abilities such as care needs, quality of life, and the three agents do not appear to improve. No improvement in quality of life, no functional ability improvement, no evidence of cost-effectiveness. Moreover, these agents provided undesirable side effects and adverse effects which depend on individual circumstances and vulnerability to adverse effects. |

| Kurlan et al., 2007 [18] | Multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled parallel groups clinical trial | 15 participating medical centers in United Sates. 40 patients satisfied the inclusion criteria. | Quetiapine group n = 20, and Placebo group n = 20 | 40 patients involved in study, dementia with Lewy bodies n = 23, Parkinson’s disease PD with dementia n = 9, Alzheimer’s disease with parkinsonism features n = 8 | Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale BPRS, Unified PD Rating Scale UPDRS, Neuropsychiatric Inventory NPI, Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination MMSE, Clinical Global Impression of Change (ADCS-CGIC), The Motor Examination component of the UPDRS for parkinsonism, and Rochester Movement Disorders Scale for Dementia (R-MDS-D) | Quetiapine began at 25 mg at bedtime, based on discussion between researchers and health professionals, the dose may titrate by 25 mg every 2 days based on efficacy for targeted symptoms and tolerability up to maximum of 150 mg twice daily. | Placebo were tablets that matched the shape of quetiapine tablets in size and color | Ten weeks of trial. the dose of quetiapine may titrate by 25 mg every 2 days based on efficacy for targeted symptoms and tolerability up to maximum 150 mg twice daily. | Quetiapine is well tolerated in dementia patients with parkinsonism. Quetiapine did not worsen parkinsonism. The titration of quetiapine did not show significant benefits in treating agitation or psychosis. |

| Grossberg et al., 2020 [19] | Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trials | Study 1, patients were enrolled by investigators at 81 sites in 7 countries: Russia (29.1% of randomized patients), the United States (27.9%), Ukraine (14.8%), Serbia (12.2%), Croatia (8.5%), Spain (4.4%), and Germany (3.0%). In Study 2, patients were enrolled by investigators at 62 sites in 9 countries: Ukraine (28.9% of randomized patients), the United States (22.6%), Russia (19.3%), Bulgaria (17.8%), Canada (4.8%), France (3.3%), Slovenia (2.2%), the United Kingdom (0.7%), and Finland (0.4%). | Study 1 performed in 81 sites in 7 countries, and Study 2 performed in 62 sites in 9 countries. (Note: Study 1 is 433 randomized, and Study 2 is 270 randomized) | Eligible patients were male or female, aged 55−90 years, with a diagnosis of dementia according to National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association | Cohen–Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) (Total score range: 29−203; higher scores indicate more frequent agitated behaviors), and Clinical Global Impression − Severity of illness (CGI-S) as related to agitation. | Study 1 (fixed dose): brexpiprazole 2 mg/day, brexpiprazole 1 mg/day, or placebo (1:1:1) for 12 weeks. Study 2 (flexible dose): brexpiprazole 0.5−2 mg/day or placebo (1:1) for 12 weeks | Brexpiprazole 0.5 mg daily n = 20. Brexpiprazole 1 mg daily n = 137, Brexpiprazole 2 mg daily n = 140 | The studies each comprised a screening period of up to 42 days, a 12-week double-blind treatment period, and a 30-day post-treatment follow-up period. | In study 1: brexpiprazole 2 mg daily demonstrated significantly greater improvement in CMAI total score from baseline to week 12 than placebo. Brexpiprazole 1 mg daily did not show significant improvement compared to placebo. In study 2: brexpiprazole 0.5–2 mg daily did not show statistical superiority over placebo. In general, brexpiprazole 2 mg daily has potential to be efficacious, safe and well-tolerated in the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia (AAD) |

| Brodaty et al., 2005 [20] | Randomized double blinded, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone for aggression and psychosis | Multi-centers of aged care facilities and nursing homes in Australia | 93 patients in total randomized in two groups, risperidone group n = 46, and placebo group n = 47 | 93 patients satisfy the inclusion criteria and fulfill BPSD of the psychosis/aggression of dementia/Alzheimer’s criteria. | Behavioral pathology in Alzheimer’s disease (BEHAVE-AD) of psychosis subscale. Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S), Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE). | The participants randomized with either a flexible dosage of risperidone (0.25 mg–1 mg daily), or placebo | Placebo were tablets that matched the shape of risperidone tablets in size and color | The follow-up was at regular bases of the baseline week, week 4, week 8 and week 12 (endpoint). | Risperidone is an effective antipsychotic agent for reducing psychosis and agitation and improves global functioning in older people diagnosed with dementia/Alzheimer’s disease and reporting with behavioral and psychological disorders. Risperidone demonstrated efficacy to moderate severe psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease/dementia. |

| Ballard et al., 2018 [21] | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study | 133 nursing homes were screened across the UK | 181 participants were randomly assigned treatment, pimavanserin n = 90 and placebo n = 91. | Participants of either sex who were aged >50 years, diagnosed of Alzheimer’s disease/dementia, and reported psychotic symptoms including visual or auditory hallucinations, delusion and/or agitation. | Mini-Mental Sate Examination (MMSE), Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Nursing Home Version (NPI-NH) Psychosis score. Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Clinical Global Impression of Change (ADCS-CGIC). Cohen–Mansfield Agitation Inventory-Short Form (CMAI-SF). | Pimavanserin initiated at TWO of 17 mg tablet daily or Placebo | Placebo were tablets matching the shape of pimavanserin tablets in size and color | The follow-up to 12 weeks. During the double-blinded period, study visits were performed at baseline and days 15, 29, 43, 64, and 85. The follow-up safety was done by telephone at 4 weeks after the last dose of study medication. | Pimavanserin with two tablets of 17 mg daily, showed efficacy in patients with Alzheimer’s disease/dementia and psychosis at the primary endpoint of 6 weeks, with an acceptable tolerability and negative effects condition |

| Ballard et al., 2005 [22] | Double blinded (clinician, patient, outcomes assessor) placebo-controlled trial | Care facilities in the North- East of UK | Three groups randomized: atypical antipsychotic (quetiapine) n = 31, cholinesterase inhibitor (rivastigmine) n = 31, and placebo (double dummy) n = 31 | 93 patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and clinically significant agitation. | Cohen–Mansfield agitation inventory for agitation measures, and Severe Impairment Battery for cognition measures. | The attained dose was 25–50 mg of quetiapine twice daily, | 3–6 mg of rivastigmine twice daily (or less than 12 mg daily between weeks 12 and week 26), and placebo | Analysis was initiated at six weeks follow up (14 quetiapine and 14 rivastigmine and 18 placebo) | Quetiapine has no superior efficacy for treatment agitation compared with placebo. Rivastigmine has no superior efficacy for treatment of agitation compared to placebo. Quetiapine demonstrated significant cognitive decline compared to rivastigmine and placebo |

| Mintzer et al., 2007 [23] | Double-blind, multi-center randomized control trials. | 81 study centers of clinical practice in the United States, Australia, Canada, South Africa, and Argentina. | 487 inpatients admitted into the hospitals with psychosis associated with Alzheimer’s disease/dementia were randomized either with aripiprazole or placebo. | Patients enrolled between 55–95 years old, that were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease/dementia, and reported with psychotic symptoms of delusions and hallucinations, who were living in nursing homes or residential aged care facilities. | NPI-NH Psychosis Subscale score for medication efficacy, Clinical Global Impression–Severity of Illness CGI-S score, BPRS Psychosis Subscale, Score and Total score, CMAI total score, MMSE score, ECGs and signs of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, and Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale. | Patients were randomized to fixed doses of aripiprazole 2 mg daily, 5 mg daily, or 10 mg daily or placebo for a 10-week period. | Placebos were tablets that matched the shape of aripiprazole tablets in size and color | Patients unable to tolerate acute phase study medication were discontinued from the study. Patients not responding by week 6 to the Clinical Global Impression-Global Improvement CGI-I score, were permitted to discontinue blinded therapy and to begin open-label treatment with aripiprazole through week 10 | Aripiprazole showed efficacy in treating both psychosis symptoms and other BPSD in elderly when compared to placebo. This study suggested that 10 mg daily is an effective dose in this patient population, although some patients may achieve symptom control at 5 mg daily. |

| Steim et al., 2008 [24] | Parallel group, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed dose trial institutionalized. | 35 aged care facilities and nursing homes in the United States. | Patients enrolled aged 55–95 years old, diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease/dementia, and who had psychotic symptoms of delusions or hallucinations at least intermittently for more than a month | A total of 256 participants were randomized into aripiprazole n = 131 or placebo n = 125 for a 10 week trial. | Neuropsychiatric Inventory Nursing Home version Psychosis Score, Clinical Global Impression CGI severity Score, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Total, Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory, Cornell Depression Scale Score | Aripiprazole dosing was flexible, started at 2 mg daily with titration to a higher dose of 5 mg, 10 mg and 15 mg daily depending on clinical judgment. The recommended titration schedule was 2 mg daily for one week, then increased to 5 mg daily for 2 weeks, then 10 mg daily for 2 weeks, and then 15 mg daily for the remainder to week 10. Decreases from higher to lower doses were allowed for tolerability only. Participant who could not tolerate 2 mg aripiprazole was dropped from the study. | Placebos were tablets matched to the shape of aripiprazole tablets in size and color | NPI-NH and CGI-S assessments were performed at randomization (baseline), and weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8 and 10. The BPRS and CMAI were assessed at baseline every 2 weeks during the study. | Aripiprazole showed no significant difference to placebo in regards to psychosis management. Aripiprazole showed significant superiority compared to placebo in regards to improvement of psychological and behavioral symptoms (including agitation, anxiety, depression). |

| Is the review question clearly and explicitly stated? | Yes |

| Were the inclusion criteria appropriate for the review question? | Yes |

| Was the search strategy appropriate? | Yes |

| Were the sources and resources used to search for studies adequate? | Yes |

| Were the criteria for appraising studies appropriate? | Yes |

| Was critical appraisal conducted by two or more reviewers independently? | Yes |

| Were there methods to minimize errors in data extraction? | Yes |

| Were the methods used to combine studies appropriate? | Yes |

| Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? | Yes |

| Were recommendations for policy and/or practice supported by the reported data? | Yes |

| Were the specific directives for new research appropriate? | Yes |

| Did the research questions and inclusion criteria for the review include the components of PICO? | Yes |

| Did the report of the review contain an explicit statement that the review methods were established prior to the conduct of the review and did the report justify any significant deviations from the protocol? | Yes |

| Did the review authors explain their selection of the study designs for inclusion in the review? | Yes |

| Did the review authors use a comprehensive literature search strategy? | Yes |

| Did the review authors perform study selection in duplicate? | Yes |

| Did the review authors perform data extraction in duplicate? | Yes |

| Did the review authors provide a list of excluded studies and justify the exclusions? | Yes |

| Did the review authors describe the included studies in adequate detail? | Yes |

| Did the review authors use a satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias (RoB) in individual studies that were included in the review? | Yes |

| Did the review authors report on the sources of funding for the studies included in the review? | No |

| If meta-analysis was performed, did the review authors use appropriate methods for statistical combination of results? | N/A |

| If meta-analysis was performed, did the review authors assess the potential impact of RoB in individual studies on the results of the meta-analysis or other evidence synthesis? | N/A |

| Did the review authors account for RoB in individual studies when interpreting/discussing the results of the review? | Yes |

| Did the review authors provide a satisfactory explanation for, and discussion of, any heterogeneity observed in the results of the review? | Yes |

| If they performed quantitative synthesis did the review authors conduct an adequate investigation of publication bias (small study bias) and discuss its likely impact on the results of the review? | N/A |

| Did the review authors report any potential sources of conflict of interest, including any funding they received for conducting the review? | N/A |

| Antipsychotic Agent | Receptors | What That Means | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quetiapine Light point: it has no motor side effects–therefore it can be used for Parkinson’s psychosis. Additionally it has no prolactin elevation. Dark point: increases weight gain and worsens metabolic diseases and cardiovascular adverse effects. | D2 antagonist, H1 antagonist, M1 and α1 antagonist (note: quetiapine has plenty of H1 antihistamine properties) | Enhances sleep, daytime sedation | Improve sleep disturbance in bipolar and unipolar depression, managing anxiety disorders. Quetiapine at 50 mg use for insomnia and sleep disturbance (this dose is small, quetiapine at this dose is full of H1 antihistamine and insufficient in amount for 5HT2c or noradrenaline or dopamine transporters. Therefore, this dose, it is not for antidepressant or antipsychotic use) Quetiapine at 300 mg is used for depression symptoms (sufficient number of 5HT2c, and it can be used as an antidepressant) Quetiapine at 800 mg is used for psychosis symptoms (at this dose, quetiapine has a wide binding profile in regards to dopamine D2, 5HT2c, 5HT1A, 5HT7, 5HT2A, 5HT2c, α receptors and H1. This variety manages psychosis symptoms. Quetiapine is approved for bipolar depression, and acute bipolar manic stage. It can be used in combination with SSRIs or SNRIs in unipolar depression that failed to respond sufficiently to antidepressants only. Quetiapine is approved for both schizophrenia and schizophrenia maintenance. |

| 5HT1a partial agonist, and 5HT2c, α2, %HT7 antagonist actions | All contribute to mood-improving properties | ||

| H1 antagonist actions in combination with 5HT2c antagonist actions | This combination contributes to weight gain and metabolic issues | ||

| Haloperidol It should NOT be given to people who have AF, ECG disturbance, respiratory failure, hyperthyroidism, temperature dysregulation, and people with lower WBCs (agranulocytosis) | Potent D2 antagonist, D3, and α1 adrenergic receptor. | Sedative, highly extrapyramidal side effects, orthostatic hypotension, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, increased risk of CVD and increased stroke, QT intervals and ECG disturbance. Highly anticholinergic effects. Increased metabolic syndrome and worsening diabetes and weight gain, hyperprolactinaemia. Worsening motor effects in parkinsonism. | Approved for acute and chronic psychosis Agitation and psychosis in bipolar disorder Managing acute manic stage It can be given in Tourette and other choreas It can be given to people suffering hallucinations due to alcohol withdrawal syndrome (if diazepam is inadequate to manage the condition) |

| Olanzapine Higher doses can be used for people who have not responded to other antipsychotics/or to lower doses of olanzapine. It should NOT be used for prolactinoma, respiratory failure, hyperthyroidism, uncontrolled diabetes or CVDs | Strong potency for D2 receptor antagonism, H1 and 5HT2A antagonist. | This combination contributes to its efficacy in improving mood and cognitive symptoms. However, it increases weight and worsens metabolic issues such as diabetes, cardiometabolic syndromes and peripheral oedema. | It is approved for managing schizophrenia, and for agitation associated with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (manic stage), and unipolar disorder. Olanzapine (5HT2c and D2) + fluoxetine (5HT2c) can be used for bipolar depression, and treatment of resistant unipolar depression. However, this combination causes weight gain and metabolic issues. It can be used with lithium OR with valproate for bipolar disorder treatment. Acute and chronic psychosis in schizophrenia Agitation in schizophrenia and acute mania |

| Risperidone Paliperidone is an active metabolite of risperidone (long-term depot injection) Dark side: increases prolactin level even at lower doses, and moderate risk of gaining weight especially with children. | 5HT2A and 5HT7 and A2 antagonist, and D2 antagonism. A1 antagonist | Contributes to the efficacy of depression Contributes to orthostatic hypotension and sedation, blurred vision. | Used for schizophrenia maintenance Bipolar mania/maintenance Used for irritability related to autistic disorder Used for self-harm, or self-injury tantrums Used for quickly changing mood Used (off-label) for treatment of agitation and psychosis associated with dementia Acute and chronic psychosis in schizophrenia |

| Aripiprazole Light side: it is well tolerated, has the lowest effect on weight gain, cardiometabolic issues, and reduces prolactin. | 5HT1A, 5HT2A, 5HT1D, 5HT2B, 5HT2C, and 5HT7 are partial agonist to antagonists. | As a partial agonist to antagonist. It has antidepressant actions and helps improve the mood disturbance. | Used for schizophrenia and maintenance. Used for treating agitation in schizophrenia and bipolar disorders (at manic stage). Approved for use irritability in children diagnosed with autism, and Tourette syndrome. Approved for adjunction use with SSRIs or SNRIs for major depression disorders. Used for managing bipolar disorder as a monotherapy. Used in combination with lithium or valproate for managing acute manic stage of bipolar disorder. It is NOT approved for managing bipolar depression. |

| D2 and D3 partial agonist | Based on these features, aripiprazole is an effective agent in treating schizophrenia/maintenance, and bipolar mania. It has relatively lower side effects and reduces prolactin rather than increases it. | ||

| H1 partial antagonism | Less sedative agent or not generally sedative | ||

| Alpha receptors of 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, 2C | Orthostatic hypotension, headache, light-headedness, | ||

| Brexpiprazole Light side: specific for agitation in dementia, and evidence of causing weight gain or sedative or increase risk of cardiometabolic issues. | It is a serotonin-dopamine-noradrenaline antagonist/partial agonist High potent 5HT2A and 5HT1A partial agonist | Acting as antidepressant, antipsychotic and managing agitation. Based on the higher potency toward alpha 1B and 2C and high potency toward 5HT2A. These properties contribute to antidepressant actions. | Approved for managing agitation in dementia Approved for treatment of schizophrenia Not approved yet for managing acute bipolar mania or bipolar depression. Brexpiprazole can be an adjunction administration with SSRI (e.g., sertraline) for managing PTSD Brexpiprazole augmented with SSRIs/SNRIs to treat unipolar major depression Approved for managing unipolar depression |

| D2 receptor partial agonism. | Specific alpha-1 actions in particular, gives a unique action for managing agitation and psychosis symptoms. | ||

| Higher potency toward Alpha 1B and Alpha 2C antagonism | This feature reduces propensity to cause motor side effects and akathisia (it can be used in parkinsonism as well). | ||

| Pimavanserin Light side: approved for managing psychosis in people with parkinsonism and people with dementia. Less risk of metabolic issues or CVD. | It is the only drug with proven antipsychotic efficacy that does not have D2 antagonism/partial agonist actions. It has a potent 5HT2A antagonism with less 5HT2c antagonism. | Strong potency against 5HT2a and 5HT2c, they improve dopamine release in both depression and the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Moreover, pimavanserin manages dementia related psychosis by reducing the overactivity of the psychosis network caused by plaques, tangles, Lewy bodies, or stroke. This action is achieved by lowering the normal 5HT2a stimulation to surviving glutamate neurons that have lost their GABA inhibition by neurodegeneration. The 5HT2a antagonism in pimavanserin is approved for managing parkinsonism disease psychosis and their positive symptoms. Additionally for managing dementia-related psychosis of all cases. | Approved for managing psychosis and depression Pimavanserin can be augmented with SSRIs/SNRIs in major depression disorders, and it can be co-administrated with D2/5HT2a/5HT1a agents for managing negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Approved for treatment of psychosis in parkinsonism Approved for managing late-stage psychosis in dementia. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qasim, H.; Simpson, M.D.; Cox, J.L. Clinical Trial Studies of Antipsychotics during Symptomatic Presentations of Agitation and/or Psychosis in Alzheimer’s Dementia: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Int. 2023, 4, 174-199. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint4030019

Qasim H, Simpson MD, Cox JL. Clinical Trial Studies of Antipsychotics during Symptomatic Presentations of Agitation and/or Psychosis in Alzheimer’s Dementia: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry International. 2023; 4(3):174-199. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint4030019

Chicago/Turabian StyleQasim, Haider, Maree Donna Simpson, and Jennifer L. Cox. 2023. "Clinical Trial Studies of Antipsychotics during Symptomatic Presentations of Agitation and/or Psychosis in Alzheimer’s Dementia: A Systematic Review" Psychiatry International 4, no. 3: 174-199. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint4030019

APA StyleQasim, H., Simpson, M. D., & Cox, J. L. (2023). Clinical Trial Studies of Antipsychotics during Symptomatic Presentations of Agitation and/or Psychosis in Alzheimer’s Dementia: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry International, 4(3), 174-199. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint4030019