Abstract

ChatGPT (Chat-Generative Pre-trained Transformer) is an accessible and innovative tool for obtaining healthcare information. This study evaluates the quality and reliability of information provided by ChatGPT 4.0® regarding Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), comparing it with responses from sleep medicine specialists. Thirty frequently asked questions about OSA were posed to ChatGPT 4.0® and two expert physicians. Responses from both sources (V1: AI and V2: Medical Experts) were blindly evaluated by a panel of six specialists using a five-point Likert scale across precision, relevance, and depth dimensions. The AI-generated responses (V1) achieved a slightly higher overall score compared to those from medical experts (V2), although the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.08). These results suggest that both sources offer comparable quality and content. Additionally, ChatGPT’s responses were clear and easily understandable, providing an accessible explanation of OSA pathology.

1. Introduction

Chatbots, such as GPT-based systems, are computer programs designed to interact with humans through text or voice. These systems leverage artificial intelligence (AI) to interpret user queries and provide relevant, automated responses. In healthcare, chatbots are used for tasks such as providing basic medical information, scheduling appointments, sending medication reminders, tracking symptoms, and offering emotional support [1]. Their primary value lies in their potential to deliver personalized and efficient patient care while reducing the workload of healthcare professionals [2,3,4].

Despite these benefits, the integration of AI into medical practice raises significant concerns. Inaccurate or inappropriate responses can lead to misdiagnosis or incorrect medical advice. Moreover, chatbots often lack empathy, which can lead to cold and unsatisfactory interactions, particularly for patients seeking emotional reassurance. Privacy is another critical issue, as sensitive medical information could be vulnerable to unauthorized access or misuse [5].

Although there is a growing body of research evaluating the accuracy and reliability of chatbot-generated responses in various medical fields [6,7,8,9], studies specifically focusing on respiratory medicine remain scarce [10].

This study aims to compare the quality and reliability of information about obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) provided by ChatGPT 4.0 with that provided by sleep medicine specialists. By analyzing responses to common patient questions, we seek to determine whether AI-based tools can serve as reliable and accessible resources for addressing concerns related to OSA.

2. Materials and Methods

Thirty frequently asked questions (FAQs) related to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) were selected. These questions represent the most common concerns raised by patients during regular consultations at the Sleep Unit (Table 1). They were compiled by experienced physicians with more than 15 years of experience in daily clinical interaction with patients with OSA. No standardized questionnaire was applied because the aim was not to stratify or measure the disease or its symptoms but rather to represent the usual doubts of the population about OSA.

Table 1.

Common questions asked by patients in clinical practice regarding obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

The selected questions cover a wide range of topics commonly encountered in medical consultations, including the definition of OSA, diagnostic approaches, standard and alternative treatments, risk factors, daily life concerns, duration of treatment, and specific considerations for populations such as children or professional drivers. The questions were formulated in Spanish using simple, colloquial language to reflect how patients usually express their concerns, avoiding technical medical jargon.

This study did not require evaluation by a research ethics committee, as no direct patient participation or intervention was involved. However, it was carried out following the ethical principles established for scientific research.

In August 2024, the selected questions were posed to ChatGPT 4.0®, an advanced natural language processing model developed by OpenAI. The AI responses were limited to five concise lines and were delivered in Spanish. In parallel, two sleep medicine specialists—a pulmonologist and an otorhinolaryngologist, both with over five years of experience treating OSA and actively involved in university teaching and training programs—answered the same thirty questions, also limited to five lines per response. Each doctor received fifteen questions independently, with specific instructions, and was unaware of the other participant’s responses.

The responses of ChatGPT (V1) and the expert doctors (V2) were blindly rated by six doctors specializing in sleep medicine from the Sleep Unit. These raters had extensive clinical experience in OSA, representing specialties including pulmonology, neurophysiology, and otorhinolaryngology. The evaluators held a Somnologist Specialist Degree from the Spanish Federation of Sleep Medicine Societies and had published research in sleep medicine.

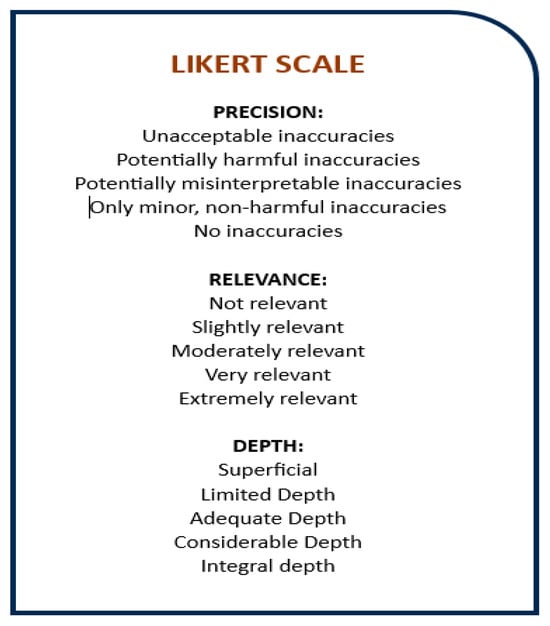

The review group was balanced in terms of gender (three men and three women), age range (30–49 years), and regional background (Spain and Latin America). The evaluators were randomly assigned to analyze one of three AI-generated (V1) or three expert-generated (V2) versions. The evaluators were blinded to the source of the responses and to each other’s identities. Each received an email containing a version with 30 responses, along with a 5-point Likert scale and explanatory guidelines for scoring (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Likert scale.

In August 2024, we posed these questions to ChatGPT 4.0®, an advanced natural language processing model developed by Open AI, and requested responses limited to five lines, in Spanish, to ensure concise responses. In parallel, two doctors who are experts in sleep medicine, a pulmonologist and an otorhinolaryngologist, are assigned to our sleep unit, where they have been working for more than five years as clinical doctors in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Both have specific training in this pathology, with activity as university professors and in training courses. They answered the same thirty questions, with the restriction of five lines. Each one received fifteen questions, with answer instructions, without knowing the other questions or the people participating in the evaluation.

The responses generated by ChatGPT and the expert doctors were evaluated and scored by six doctors who are experts in sleep medicine, belonging to the Sleep Unit of our hospital, using a Likert scale

The six doctors had extensive clinical experience in the pathology of obstructive sleep apnea, each in their specialty (pneumology, neurophysiology, and otorhinolaryngology), with specific training in sleep medicine, publications on the disease, and a somnologist specialist degree from the Federation of Spanish Medical Societies.

Homogenization was sought in the evaluation group with three men and three women of similar ages (30–49 years) who were Spanish speakers, originally from Spain and Latin America. Three versions of V1 (artificial intelligence) and three versions of V2 (expert physician) answers were distributed among the six doctors. The evaluators did not know the source of the answers or even who was participating in the evaluation. They received an email with the randomly assigned version with 30 responses and the Likert scale in the 3 dimensions along with each question. They were provided with an explanatory legend to define each score (Figure 1).

The Likert scale, a widely recognized psychometric tool, was used to assess three dimensions: precision, relevance, and depth. Each dimension was rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) [11]. This method allowed for quantifying subjective assessments in an ordinal format suitable for comparative analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics® Version 25. Paired-sample t-tests were applied to compare the two response sets, and a sub-analysis was conducted across the three evaluation dimensions (precision, relevance, and depth).

3. Results

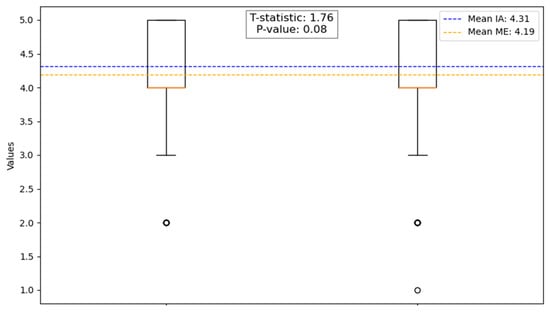

The responses provided by artificial intelligence (V1) achieved a slightly higher average score of 4.31 (±SD 0.804) on the Likert scale compared to 4.19 (±SD 0.861) for the expert doctor (V2). However, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.08) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis between artificial intelligence and the expert physician. In the first column on the left (Artificial Intelligence) and in the second column on the right (Medical Expert).

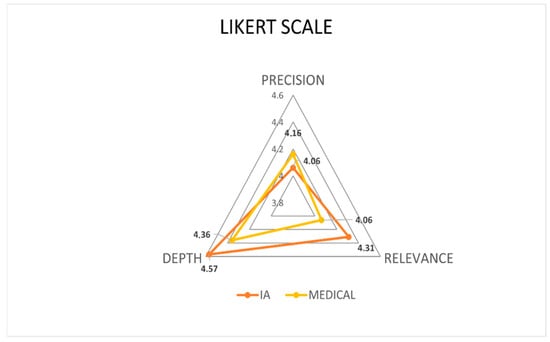

In the sub-analysis across the three evaluated dimensions, the following results were derived:

- Precision: The physician responses (V2A) achieved a slightly higher average score (4.16 ± 0.982) compared to the AI responses (V1A: 4.06 ± 0.928). This difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.869).

- Relevance: The AI responses scored higher (4.31 ± 0.774) than the physician responses (4.06 ± 0.676), but the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.435).

- Depth: AI responses also scored higher (4.57 ± 0.601) than the physician responses (4.36 ± 0.878), but this difference did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.067) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Likert scale comparison: Artificial intelligence vs. the expert physician across the three assessed dimensions.

Figure 3. Likert scale comparison: Artificial intelligence vs. the expert physician across the three assessed dimensions.

These findings indicate that while the AI-generated responses demonstrated slightly higher scores in relevance and depth, and the physician responses performed marginally better in precision, none of these differences were statistically significant. This suggests a high degree of comparability between the two response sources across all evaluated dimensions.

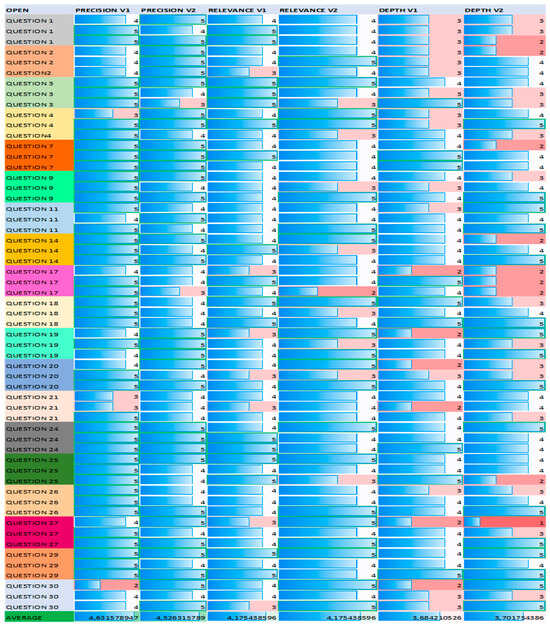

In the individual analysis of each question, some differences were found, mainly marked by whether the answers were open and/or closed, taking into account the use of semantic resources in the answers, which can provide evaluations and differentiations in the interpretation.

Of the 30 questions, 11 were closed questions and 19 were open. The overall results were analyzed, as well as by subgroups of the three rating scales. The overall average value of the closed responses was 4.42 compared to 4.15 for the open ones.

Closed-ended questions, in general, elicit more relevant responses that are closely aligned with the question and provide useful information. This is because closed-ended questions limit the range of possible answers, making it easier to obtain accurate and specific data. In our analysis, the averages in the relevance of closed-ended responses for the artificial intelligence group (V1) and the expert physician group (V2) were very similar, with averages of 4.48 (±0.657) and 4.33 (±0.682), respectively. Student’s t-test did not show a statistically significant difference between the two groups (p > 0.29), indicating that both groups provided responses of comparable relevance to these types of questions, with similar data on the accuracy scale, which relates to the accuracy of the information provided. An accurate response provides correct and well-founded data, while an inaccurate response may contain errors or generalizations that can lead to misunderstandings. In our analysis, the average accuracy of these closed-ended questions was 4.88 (±0.326) for the artificial intelligence group (V1) versus 4.67 (±0.636) for the medical expert group (V2), with Student’s t-test showing no significant difference (p > 0.12).

However, in the depth analysis of the closed questions, we found a notable exception with respect to the rest of the subscales, with statistically significant differences (p = 0.0016), with an average of 4.33 (±0.876) for the artificial intelligence group (V1) versus 3.85 (±0.857) for the expert physician group (V2). These findings are of particular relevance when considering a deeper response generated by ChatGPT; this would mean that it offers a detailed analysis, including examples and nuances that enrich the understanding of the topic, as opposed to a more superficial response that is limited to a simple statement without exploring the implications or contexts. In this sense, we must consider the rest of the results, because questions that have the potential to provide more in-depth answers do not always translate into greater relevance or accuracy.

On the other hand, open-ended questions obtain answers with lower scores than closed-ended ones; this could be due to the fact that they provide a greater number of elements within the answers, which could deviate from the topic or include information that does not add value to the query. This is due to the freer nature of open-ended questions, which allows respondents to interpret the question in a variety of ways and respond with greater variability. In our analysis, the values were slightly higher in the AI group, but none of the subscales showed a statistically significant difference between the two groups (p > 0.05); the values of the open-ended responses for the AI group (V1) and for the expert physician group (V2) on the three scales are detailed below in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Visual graph of the scores for the questions considered open-ended. See the lowest values obtained in the depth subscale.

Another point of evaluation was to compare the scores of the evaluators with each other. For this, we used an analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a result of 0.52 (p > 0.05), which suggests that the differences observed in the scores of the evaluators are not large enough to conclude that there is significant variability between them; therefore, the consistency of the evaluations is reinforced, both in V1 and V2.

4. Discussion

In general, the artificial intelligence (V1) group achieved slightly higher scores than the medical expert (V2) group. However, Student’s t-test revealed no statistically significant differences between the responses from V1 and V2 across most questions in the categories of precision, relevance, and depth. This suggests that the answers from both groups were quite similar in these dimensions. In the accuracy analysis, the scores showed more variation without a clear trend. Both groups achieved high average scores on the Likert scale, consistently above 4 out of 5, indicating quality responses [5]. These findings underscore the reliability of the information provided by artificial intelligence in the context of a prevalent condition like OSA, which requires significant human and technical resources for treatment. AI tools could serve as informative support to address questions, promote treatment adherence, and reduce misunderstandings [6].

In similar research, Mira et al. [7] assessed the agreement between ChatGPT’s responses and those of expert otolaryngologists regarding OSA in clinical case scenarios. They found that ChatGPT provided the same response as the experts in over 75% of the cases. However, from a statistical standpoint, ChatGPT’s responses differed significantly from the experts’ opinions (p = 0.0009). The authors attributed this discrepancy to the complexity of managing obstructive sleep disorders, where multiple therapeutic options exist and the literature often lacks definitive guidance for selecting the optimal approach for each clinical case.

One notable aspect of this study is the ability of the artificial intelligence (AI) system to provide information with a high level of depth, even in responses limited to five lines. This capacity for synthesis without sacrificing essential content is a remarkable feature of advanced models like GPT-4. In the depth evaluation, which measures not only the amount of detail but also its quality and relevance, the AI system achieved higher scores compared to medical experts, suggesting a significant efficiency in condensing complex information into accessible and concise answers. This point has already been explored in other studies, such as the article by Hake et al., where it was observed that language models like ChatGPT can synthesize complex medical information in a concise yet profound manner, with performance comparable to summaries generated by human experts [8].

Recently, researchers published an opinion article, evaluating the best way to use ChatGPT in scientific research, and came to the conclusion that as natural language processing is optimized, it can help scientists in guiding the more creative and complicated aspects of downloading less scientifically stimulating aspects; however, the current challenge is to identify the tasks that only humans can perform and recognize the limitations that chatbots still pose [9].

One strength of our study is the use of GPT-4, which offers more advanced capabilities than previous versions such as GPT-3.5 and GPT-3. GPT-4 provides a deeper understanding of context, generates more coherent responses, and handles ambiguity better. Unlike simpler chatbots that rely on predefined responses or strict rules, GPT-4 produces answers based on patterns learned during training, which allows for more natural and adaptable responses [10]. This likely contributed to the consistent and higher scores, particularly in the relevance and depth of the information provided. Furthermore, our study stands out from others [11,12,13] by comparing ChatGPT’s responses directly with those of medical professionals.

The use of the Likert scale in our study provided a structured approach to assess the quality of responses from both artificial intelligence and expert physicians. This scale, with a scoring range from 1 to 5, allows for the quantification of evaluators’ subjective perceptions in terms of accuracy, relevance, and depth. Its simplicity and effectiveness in measuring attitudes or perceptions have made it a widely used tool in medical research.

However, other scales could complement the evaluation of information quality, such as the DISCERN scale, developed to assess the quality of information about medical treatments, and the AIPI scale (Assessment of Information Quality in Health Websites), which is used to evaluate the quality of health-related information on websites. Incorporating these scales in future studies could offer a broader and more detailed perspective on the responses generated by artificial intelligence compared to human experts [12].

As a limitation, we acknowledge the relatively small number of expert physicians who evaluated the responses—only six compared to other studies where evaluators were from multiple countries and exceeded one hundred [13,14]. However, we mitigated this limitation by ensuring that all six evaluators were expert sleep physicians from different specialties (neurophysiology, pulmonology, and otorhinolaryngology). This multidisciplinary approach strengthened the evaluation, and we also incorporated the perspective of a sleep specialist, pulmonologist, and another otorhinolaryngologist in the answers generated to the common questions asked by patients about obstructive sleep apnea to provide a broader view. However, we believe that increasing the number of evaluators in the questions of both versions, even in different languages, would be very interesting in order to see the response capacity with less bias, greater consistency between evaluators, and the differences in relation to language. In fact, we performed a calculation of the effect size, measuring the magnitude of the difference between the two groups (difference in means between the two groups divided by the combined standard deviation) and obtained an average value, whereby 10 people per group would be needed to detect significant differences between V1 and V2 with a statistical power of 80% and a significance level of 5%.

It seems important to us to carry out a reflection on the evolution of technology as the implementation of new technological resources in our daily lives is a progressive constant. As Darwin [14] said, in the evolution of species through natural selection, it is not the smartest or the strongest who survives the most but the one who best adapts to change. Human beings must know how to integrate these changes and adapt to them in an intelligent way, in their daily life and in each of their more direct or indirect areas, with millions of possibilities, but always with the knowledge and control of the risks and benefits. In medicine, in terms of the knowledge of diseases, the accessibility of information is very important, in addition to it meeting the characteristics of being rigorous, reliable, and understandable, because this builds a well-trained population, trained for self-care and with a tendency towards healthier habits with more stable and committed management of their treatment.

However, when discussing artificial intelligence, it is crucial to consider the ethical implications of its use. The deployment of a reliable AI system necessitates adherence to a comprehensive set of requirements, including human oversight, technical robustness, data privacy management, transparency, diversity, non-discrimination, equity, social and environmental well-being, and accountability [15]. This process mandates third-party review in quality management and the compilation of necessary documentation. Validation and verification of these tools are essential to demonstrate clinical benefits and to provide a clear description of the intended purpose. It is imperative to note that any modification in the intended purpose would necessitate a new conformity assessment.

5. Conclusions

ChatGPT demonstrated accuracy and reliability in addressing common questions about obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), with no statistically significant differences compared to responses provided by medical experts. The AI-generated answers were clear, accessible, and easy to understand, offering valuable educational support for patients.

We believe that ChatGPT can serve as an effective tool for patient education, particularly when used under the direct supervision of healthcare professionals. While chatbots are only one component of the broader integration of artificial intelligence in healthcare, their potential to enhance patient understanding, support treatment adherence, and improve healthcare efficiency is undeniable.

Future research should continue exploring the best practices for integrating AI tools into clinical workflows, ensuring their responsible and effective use in patient care.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the manuscript as follows: Conceptualization, C.L.-R. and J.R.-A.; methodology, C.L.-R. and J.R.-A.; software C.L.-R.; formal analysis C.L.-R. and B.R.M.; investigation, C.L.-R. and J.R.-A.; resources A.A.F., J.R.-A., L.S.P., C.V., J.M.D.G., I.A.R., N.L.R., S.C.P. and F.G.P.; writing—review and editing C.L.-R. and J.R.-A.; visualization, C.L.-R. and J.R.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant, deidentified data supporting the findings of this study are reported within the article.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the multidisciplinary High Specialty Sleep Unit of the University Hospital of Getafe (Madrid) Spain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dave, T.; Athaluri, S.A.; Singh, S. ChatGPT in medicine: An overview of its applications, advantages, limitations, future prospects, and ethical considerations. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1169595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riestra-Ayora, J.; Vaduva, C.; Esteban-Sánchez, J.; Garrote-Garrote, M.; Fernández-Navarro, C.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, C.; Martin-Sanz, E. ChatGPT as an information tool in rhinology. Can we trust each other today? Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 3253–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edalati, S.; Vasan, V.; Cheng, C.P.; Patel, Z.; Govindaraj, S.; Iloreta, A.M. Can GPT-4 revolutionize otolaryngology? Navigating opportunities and ethical considerations. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2024, 45, 104303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, E.T.; Florian-Rodriguez, M. Human vs machine: Identifying ChatGPT-generated abstracts in Gynecology and Urogynecology. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 231, 276.e1–276.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 22, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Garbarino, S. Assessing the Accuracy of Generative Conversational Artificial Intelligence in Debunking Sleep Health Myths: Mixed Methods Comparative Study with Expert Analysis. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e55762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira, F.A.; Favier, V.; Dos Santos Sobreira Nunes, H.; De Castro, J.V.; Carsuzaa, F.; Meccariello, G.; Vicini, C.; De Vito, A.; Lechien, J.R.; Chiesa-Estomba, C.; et al. Chat GPT for the management of obstructive sleep apnea: Do we have a polar star? Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 2087–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hake, J.; Crowley, M.; Coy, A.; Shanks, D.; Eoff, A.; Kirmer-Voss, K.; Dhanda, G.; Parente, D.J. Quality, Accuracy, and Bias in ChatGPT-Based Summarization of Medical Abstracts. Ann. Fam. Med. 2024, 22, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pividori, M. Chatbots in science: What can ChatGPT do for you? Nature 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.-Y.; Cheng, P.-Y.; Deng, J.-H.; Jaw, F.-S.; Yii, S.-C. ChatGPT v4 outperforming v3.5 on cancer treatment recommendations in quality, clinical guideline, and expert opinion concordance. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241269538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciberras, M.; Farrugia, Y.; Gordon, H.; Furfaro, F.; Allocca, M.; Torres, J.; Arebi, N.; Fiorino, G.; Iacucci, M.; Verstockt, B.; et al. Accuracy of Information given by ChatGPT for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Relation to ECCO Guidelines. J. Crohns Colitis 2024, 18, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Maniaci, A.; Gengler, I.; Hans, S.; Chiesa-Estomba, C.M.; Vaira, L.A. Validity and reliability of an instrument evaluating the performance of intelligent chatbot: The Artificial Intelligence Performance Instrument (AIPI). Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 2063–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, B.M.; Bodnar, M.S.; Moore, A.D.; Maseda, M.C.; Kucharik, M.P.; Diaz, C.C.; Schmidt, C.M.; Mir, H.R. Is ChatGPT a trusted source of information for total hip and knee arthroplasty patients? Bone Jt. Open 2024, 5, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwin, C.; Kebler, L. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or, the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life: J. Murray, 1859. Murray. 1859. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/06017473/ (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Hagendorff, T. The Ethics of AI Ethics: An Evaluation of Guidelines. Minds Mach. 2020, 30, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).