1. Introduction

When it comes to mass media, television commercials or TVCs are considered powerful tools. TVCs influence buying behaviors, increase the sales of products, produce messages, entertain people, transmit cultural values, and convey information (

Dermawan & Barkah, 2022;

Jolodar & Ansari, 2011;

Srikandath, 1991). Over the years, one of the biggest concerns among communication scholars has been how TVCs represent genders (

Furnham & Mak, 1999;

Kim & Lowry, 2005;

Silverstein & Silverstein, 1974;

Milner & Higgs, 2004) and thus play a vital role in reinforcing gender stereotypes, perpetuating traditional roles, and presenting unrealistic and cliché images of femininity and masculinity (

Milner & Higgs, 2004;

Valls-Fernández & Martínez-Vicente, 2007), which are even harmful in many aspects. Advertisements have a vital influence on the perceptions men deem valid regarding their gender identity (

Eisend, 2010). Although they may take their references from various sources, including family, peers, sports, and other media, men persist in reaffirming the messages disseminated by markets (

Zayer et al., 2019).

India, the second-largest populated country in the world, with a population of more than 1.4 billion (

Nationsonline.org, 2022), and a hub of cultural richness and diversity, also has 22 officially recognized languages and 398 dialects, and the impact of television and its content on the audience has a vast impact on Indian society. Between 2011 and 2020, India witnessed a substantial change in advertisements’ substance and message quality. Over the last decade, Indian television commercials (TVCs) have evolved from repetitive, product-focused messaging to more creative storytelling that aligns with brand values. Modern TVCs now emphasize deeper consumer insights and social themes, moving beyond just listing product features (

Gupta & Siri, 2021). This shift has enhanced their aesthetic appeal, presentation styles, and cultural relevance, making them more engaging and meaningful to audiences (

Gupta & Siri, 2021). Additionally,

Dash (

2020) analyzed 538 Indian TV commercials in 2018 to examine the use of global, local, and glocal cultural appeals, finding that glocal appeals are most common, followed by global appeals, with local appeals being rare in Indian TV commercials. The research reveals a strong global influence in the cultural blending within contemporary Indian TV commercials, which was missing in earlier decades. Some of the most common global appeals that dominated Indian TVCs contained explicit display and discussion of sex, low power distance, individualism, technological dependence on machines, etc. (

Dash, 2020). Nevertheless, how much of that change is reflected in gender portrayals? This study explores how the Indian TVC industry has depicted differences in gender representations from 2011 to 2020.

The root of the differences in gender portrayals in Indian TVCs lies in societal norms and expectations. For instance, by applying content analysis,

Matthes et al. (

2016) found that a country’s culture significantly impacts how gender roles are portrayed in media. Due to cultural and historical factors, India’s patriarchal society plays a significant role in portraying gender in the media (

Gaur & Sarkar, 2024;

Prabhash, 2005;

Roy, 1998). TVCs are a powerful medium of communication. They reflect and strengthen these societal norms, forming the audience’s understanding of gender roles. For example, after a qualitative content analysis of 210 Indian TV commercials,

Prasad (

1994) found that most advertisements showed women as housewives, mothers, or sisters instead of as individuals. On the other hand, men are shown in more dominant positions, such as decision-makers, in Indian TV commercials (

Sarkar, 2015). Promoting gender differences is a barrier to overcoming gender stereotypes in the media. While Prasad’s seminal study provided a foundational analysis of women’s portrayal on television, this study expands that scope by examining the representation of both genders. It also updates the inquiry by incorporating content from the digital era, reflecting shifts in media production and consumption over time. Additionally, this study introduces a quantitative dimension to the analysis, offering a broader empirical perspective that complements the earlier qualitative focus.

By analyzing television advertisements from 2011 to 2020, this study explores how gender representations between males and females are differentiated in Indian TVCs. Since this study was conducted in 2023, and by that time, most of the TVCs from the sample were not being circulated on TV channels anymore, TVCs were collected from YouTube. Combining this analysis with the application of previously known variables from the past, this study tries to minimize the gap in the less-researched topic of gender representations in developing and underdeveloped nations. This global viewpoint is crucial because it offers a more comprehensive picture of the field, which is still dominated mainly by research from the Western and more developed nations (

Prieler & Centeno, 2013). This research does not claim to measure the effects of how TVCs influence the spread of gender stereotypes. However, given the quantitative content analysis method this study will use, those findings can serve as a helpful starting point for research into one of the many social effects that media can have.

2. Historical Background

It was the resurgence of the women’s movement in the 1960s that raised a voice about the portrayal of women in the mass media (

Rakow, 1986). This was when the feminists successfully called attention to the differences between social and biological aspects of men and women. Advertisements came under the scrutiny of feminists because of the stereotypical and unrealistic depiction of women as sex objects, happy homemakers, dependent on their husbands, incompetent, and in ornamental roles (

Courtney & Whipple, 1983;

Ferguson et al., 1990;

Lee, 2004;

Milner & Higgs, 2004). Women were seen to be restricted to duties related to their “place” in the home, such as wife, mother, sex object, and housekeeper, whereas men were seen to be free to go everywhere else (

Welter, 1966).

However, it was not until the 1970s that a large number of studies were systematically conducted to explore the link between portraying males and females in media and promoting gender stereotypes (

Courtney & Whipple, 1983). According to

Ahlstrand (

2007), one of the pioneering studies of gender representation in television advertisements was conducted by

McArthur and Resko (

1975). The scholars analyzed 199 randomly selected American TVCs quantitatively (

Ahlstrand, 2007). They developed a coding scheme to analyze seven variables: sex, product user, product authority, role, setting, product category, and scientific/non-scientific roles. This coding scheme was the most widely used worldwide in similar studies applying the same or revised coding scheme, particularly when the researchers wanted to see the comparisons within and between different countries and the prominent advertising trends (

Ahlstrand, 2007).

Subsequent studies in the backdrop of relatively modern times also showed similar findings. As

Grau and Zotos (

2016) showed in their meta-analysis of scholarship related to gender stereotypes, women are often portrayed as weak and second-class citizens in advertisements (

Ahlstrand, 2007). Consumer culture often reinforces gender stereotypes, portraying both men and women in reductive ways—particularly depicting women as submissive, subordinate, silent, and passive (

Ali, 2018); motionless, aesthetic models whose roles are many a times ornamental (

Lee, 2004). On the other hand, men are shown as being dominant and making decisions (

Lee, 2004), experts in the workplace, the narrator of decisions about the home, economy, and family (

Sarkar, 2015). Also, men are mostly portrayed as authoritative, independent, more persuasive than women (

Van Hellemont & Van den Bulck, 2012), and are found in occupational settings more than women (

Eisend, 2010).

India’s television broadcasting landscape is vast and diverse, reflecting the country’s multifaceted cultural and linguistic fabric. As

“India Profile—Media” (

2019), a study conducted by BBC News highlights, India has 900 private satellite TV stations, around half of which are news channels. OTT streaming platforms, along with multichannel satellite TV, are very popular among the audiences. According to

Reporters Without Borders (

2024), India’s public TV broadcaster

Doordarshan operates in 23 languages in India and is watched by millions of viewers. In India, 1.4 billion inhabitants and 210 million homes have access to television sets. This extensive network ensures that television remains a primary medium for information and entertainment across urban and rural areas.

3. Theoretical View

This study uses a dual-theoretical lens—cultivation theory and framing theory—to understand how gender stereotypes are portrayed in Indian TVCs. Although many studies have found common trends like the numerical dominance of the male primary characters over the female primary characters, or the heavy presence of female characters in the domestic roles, this study attempts to transcend simple repetitions by theoretically unpacking the underlying mechanisms of these representations and their persistence in the dynamic environment of a non-western, developing country like India.

Introduced by George Gerbner (

Gerbner & Gross, 1976) cultivation theory holds that viewers’ impressions about reality are shaped over time by long-term, cumulative exposure to television content. This argument is especially pertinent given TVCs are so common in India’s huge media environment, where television still rules (

“India Profile—Media”, 2019). For example, as a qualitative study conducted by

Akram (

2025) shows, the way South Asian TVCs emphasize skin lightening products and focus on fair complexions influences audiences to conform to a narrow standard of beauty and fosters very high demand for skin lightening products. Due to constant delivery and reinforcement of the same message that “fair skin is synonymous to beauty”, dark skin is perceived to be undesirable by people in the South Asian region, and skin-lightening products have a very lucrative market (

Akram, 2025).

Putting this perspective in the context of this study, constant exposure to consistent gendered representations—such as women routinely being shown in the caring or domestic roles, or males especially in the professional or authoritative spheres—can gently foster and normalize these images in the brains of the viewers. Cultivation theory helps position stereotypical gender portrayals not merely as a reflection of existing social norms, but as a part of a larger media system that contributes to their visibility and persistence. The more people watch television, the more their views are impacted by the narratives spread by television (

Gerbner & Gross, 1976). Gerber and his colleagues later expanded this theory by introducing two more concepts:

mainstreaming—where heavy viewing tends to minimize distinctions in world view across various social groups—and

resonance, which describes how media messages become more powerful when they align with viewers’ real life experiences. These ideas enrich our understanding of how gender norms may become broadly accepted or even intensified within diverse audience segments.

Secondly, while this study does not evaluate the audience’s perceptions or responses, it draws selectively from framing theory to support the analysis of how gender roles are visually and narratively constructed in advertisements. Originating in the work of

Goffman (

1974) and later refined by

Entman (

1993), framing theory emphasizes how media selectively portrays and stresses particular facets of reality to shape the audience’s interpretation of events or ideas. By their very nature, ads use visual emphasis, strategic message and images to create certain frames around the items and the people they highlight. By means of strategic framing, advertisers create gender narratives—that is, regularly positioning males in positions of control, authority or problem solving, or women in roles connected with family and emotional labor. On the other hand, when women are consistently framed in nurturing or supportive roles, this repetition reinforces a narrow set of societal expectations about femininity (

Goffman, 1974;

Lindner, 2004).

Santoniccolo et al. (

2023) observed that advertisers aim to create a sense of comfort and acceptance by aligning their advertisements with the prevailing cultural values, which aligns with framing theory’s core logic of selection and emphasis. TVCs strategically tap into gender-specific stereotypes and narratives to shape how the characters and roles are portrayed and perceived. Through careful decisions in visual compositions, character positioning, non-verbal indications, voiceovers, and location choices that either openly or implicitly embed society gender expectations and norms, framing theory is essential for helping to understand not just what is shown but also, how it is displayed.

These theoretical angles, taken together, help to shape the approach of the study. The core ideas of these two theories directly affected the operationalizing of variables in the codebook and the study design. Cultivation theory guided the decision to utilize a decade-long sampling frame, supporting the selection of a period extensive enough to assess the cumulative nature of consistent gender portrayals in Indian TVCs. This approach allows for an examination of the overall patterns that viewers are repeatedly exposed to, contributing to their perceptions of reality. Framing theory influenced the construction of the specific coding categories—particularly the inclusion of variables such as character setting, types of roles performed, and voiceover genders, which are the key tools advertisers use to construct and emphasize gender frames. In this way, the theoretical framework shaped not only the interpretive lens for the findings, but also the precise selection and operationalization of the study’s empirical variables.

4. Research Hypotheses

Considering all the above-mentioned aspects, numbers establish numerical differences and systems of worth that rank people or organizations according to better or worse/more or less (

Mau, 2019). According to Hofstede’s Masculinity Index (

Hofstede, 2013), India’s score is 56, making it the fourth-ranked Asian masculine country, preceded by Japan, China, and the Philippines. Media consumers observe this numerical superiority of males over females daily through the TVCs. In that case, chances are high that the advertisers, who are also a part of the same population, will emphasize portraying the male predominance on screen more than the females as the primary characters. Research has found that male characters comprise most of the primary characters in TVCs (

Eisend, 2010;

Furnham & Paltzer, 2010;

Ganahl et al., 2003;

Santoniccolo et al., 2023). Based on these findings, the first hypothesis is

H1. More males than females will appear in Indian TVCs as primary characters.

One of the most used variables in studying gender representation in TVCs is voice-overs (

Matthes et al., 2016). A robust finding in the research is the prevalence of male voiceovers, which are frequently regarded as the “voice of authority” (

Silverstein & Silverstein, 1974;

Van Hellemont & Van den Bulck, 2012). Studies often find a predominance of male voiceovers over female voiceovers in TVCs (

Furnham & Paltzer, 2010;

Furnham & Voli, 1989;

Matthes et al., 2016;

Prieler & Centeno, 2013;

Valls-Fernández & Martínez-Vicente, 2007).

Furnham and Mak (

1999) found this aspect more evident in Asia than elsewhere. Hence, the second hypothesis is

H2. There are more male than female voiceovers in Indian TVCs.

Including the precise forms and types of portrayals may disclose society’s respect or lack thereof for a particular social group because numerical representation alone does not indicate the quality of the representations (

Signorielli & Bacue, 1999). In India, women are working more than ever before. In 2001, the Indian government declared that year the “Year of Women’s Empowerment” and introduced the National Policy for the Advancement of Women (

Kumari & Siotra, 2023). The India Employment Report (IER) 2024, published by the Institute for Human Dev and the International Labor Organization, showed that whereas the female labor force participation rate (FLFPR) was 38.9% in 2000, it increased to 46.8% during the 2017–2018 period and 58.2% in 2023–2024 (

Kumar & ET BFSI, 2024;

Pathak, 2024). But the patriarchal family structure and societal values remain essentially unchanged (

Roy, 1998), which does not allow Indian media to work as agents of social change and freedom for women (

Prabhash, 2005).

Eisend (

2010) showed, in his meta-analysis of television and radio advertisements, that the chances of women being depicted at home are 3.5 times higher than men being shown at home. Men are most often depicted in the public realm of employment, while women are restricted to a life of domesticity and family, in a home setting (

Das, 2010;

Gaur & Sarkar, 2024;

Knoll et al., 2011;

Prieler & Centeno, 2013;

Roy, 1998). Regarding the occupations of the primary characters, several studies have revealed highly stereotypical findings showing women as homemakers (

Lee, 2004;

Santoniccolo et al., 2023) and men as working characters (

Arima, 2003;

Santoniccolo et al., 2023).

Sarkar (

2015) argues that Indian TVCs for a wide range of products, from bathing soap to cuisine spices, portray women as homemakers who show their skills in household chores. Also, in the Hindu religion, the ancient code of Manu and the ancient ideology of “Pativrata” (i.e., a woman who is sincerely obedient to her husband) have encouraged women to be dependent from cradle to the grave (

Roy, 1998). Hence, the following are hypothesized:

H3a. More females than males will be depicted in home settings in Indian TVCs.

H3b. More males than females will be depicted in outdoor and workplace settings in Indian TVCs.

There are few consistent findings and gender portrayals, which could be because different studies frequently use different product categories (

Prieler & Centeno, 2013). Most studies showed a strong connection between women and home and household products such as toiletries, cosmetics, and cleaning products (

Furnham & Paltzer, 2010;

Arima, 2003) and cooking products such as rice, oil, or cuisine spices (

Sarkar, 2015). On the other hand, men are portrayed in television advertisements for telecommunication, electronics, computers, technology, cars (

Das, 2010;

Furnham et al., 2000;

Ganahl et al., 2003;

Matthes et al., 2016), agricultural and industrial goods, bikes (

Sarkar, 2015), and medical and financial services (

Rubio, 2018;

Sarkar, 2015). Thus, the following hypotheses are offered:

H4a. More females than males will be depicted in Indian TVCs for home and household products.

H4b. More males than females will be associated with the TVCs of banking and technology, development, healthcare, and transportation in Indian television advertisements.

5. Method

The current study aims to identify the gender representations employed in TVCs in India between 2011 and 2020 and applies the content analysis method as a research approach. The lead author used a purposive sampling strategy based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria during the fall of 2023. A total of 120 TVCs were analyzed based on their prominence in the commercial sector. This study chose a sample size of 120, keeping the exclusion criteria in mind. The sample size is enough to have statistical power to identify the trends in a decade and makes it manageable to analyze each advertisement thoroughly. All television commercials were cast on major Indian entertainment channels. A stratified purposive sampling strategy was employed to ensure representation across different product categories and time periods, focusing on commercials that are prominent and easily accessible. A total of 120 unique television commercials released between 2011 and 2020 were selected for detailed analysis. This sample size was determined based on a careful consideration of several factors. Given the study’s focus on Hindi-language commercials only—excluding regional or non-Hindi advertisements—and limiting selection to one TVC per brand, the pool was intentionally narrowed. All commercials were sourced from YouTube due to the fact these TVCs from the assigned timeframe were not being circulated on TV channels anymore, requiring careful verifications of their actual release dates to ensure they matched the intended time period. Additionally, the selection was guided by several product categories relevant to the study’s objectives. Due to these deliberate criteria and the emphasis on authenticity and thematic consistencies, the available and suitable dataset naturally totaled 120 TVCs.

Content analysis was chosen as the primary research method due to its ability to systematically and objectively quantify patterns in communication, particularly in visual and verbal content like television commercials. According to

Maier (

2017), content analysis is a valuable descriptive tool that enables researchers to study patterns and communication processes over time, such as rhetorical strategies in political speeches. However, content analysis alone cannot establish cause-and-effect relationships between messages and their outcomes. To make causal claims, it needs to be combined with other methods or used as a foundation for further research (

Maier, 2017). These considerations were carefully accounted for during the research design and coding process.

There was no fixed number of advertisements for any category. Coding instruments were developed to gather data to test the hypotheses posed. After that, the lead author beta-tested a sample frame to ensure that the coding sheet met the criteria of the variables that were being analyzed. These details are provided in the Coding & Analysis section of the Method chapter.

6. Results

The results of this study were based on chi-square analysis and descriptive statistics that were performed on a total of 120 unduplicated Indian television advertisements as samples. Samples were collected from the video-sharing platform YouTube. Collected samples consisted of 40% home/household (n = 48), 24% banking and technology (n = 29), 13% transportation (n = 16), 10% development (n = 12), 6% healthcare (n = 8), and 0.05% other (n = 7) category of products. Approximately 33% of these commercials were uploaded by advertising agencies that were directly involved in their production (n = 40), 59% were uploaded by the products’ official YouTube channels (n = 71), and 8% were uploaded by individuals who were either costume designers or models for the TVC or random individual uploaders who mentioned the advertisement circulation date in the headline or in the description, or their upload date was matched with the product’s official launch date (n = 8%).

The TVCs in this study averaged M = 1,483,425 views and M = 3165.1 likes, with the YouTube Channels averaging M = 175,094 subscribers.

The samples contained seven TVCs from 2011 (5.8%), nine TVCs from 2012 (7.5%), 11 TVCs from 2013 (9.1%), seven TVCs from 2014 (5.8%), 20 TVCs from 2015 (16%), 12 TVCs from 2016 (10%), 22 TVCs from 2017 (19%), 10 TVCs from 2018 (8.3%), 12 TVCs from 2019 (10%), and 10 TVCs from 2020 (8.3%).

Figure 1 presents an at-a-glance picture of the number of TVCs collected for this study that were released between 2011 and 2020.

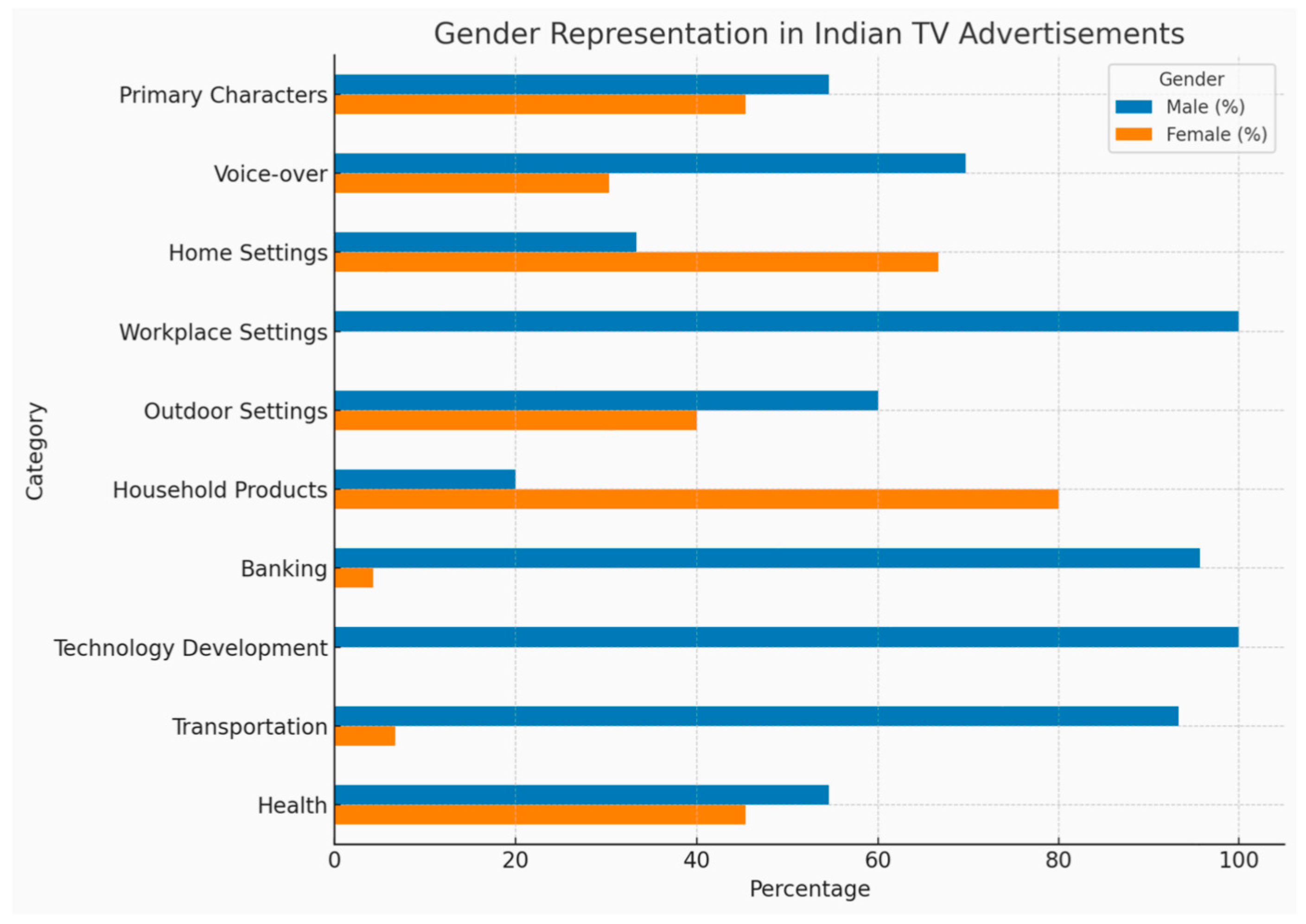

H1 hypothesized that more males than females will appear in Indian television advertisements as primary characters. To test this hypothesis, descriptive statistics were computed. In the total sample of n = 120, advertisements with a primary character totaled n = 108. Males scored higher (N = 59, 54.6%) than females (N = 49, 45.4%) as primary characters in Indian television advertisements. The findings from this test support H1.

To test H2, which hypothesized there will be more male voiceovers than female voiceovers in Indian television advertisements, a chi-square analysis was conducted. The results found significant differences χ2 (1, N = 89) = 32.20, p < 0.001 between male and female voiceovers. Male voiceovers were significantly higher (69.7%) than female voiceovers (30.3%). This finding supports H2.

H3a hypothesized that more females than males are depicted in home settings in Indian television advertisements; a chi-square analysis was performed. The results found significant differences χ2 (1, N = 108) = 12.57, p < 0.001 between male and female portrayal in home settings. Females were shown in home settings significantly more frequently (66.7%) than males (33.3%). Thus, H3a is supported.

To test H3b, which stated that more males than females will be depicted in outdoor and workplace settings in Indian television advertisements, a chi-square analysis was performed. The results found significant differences χ2 (1, N = 108) = 13.36, p < 0.001 between male and female portrayal in workplace settings. Males were shown in workplace settings significantly more frequently (100%) than females (0%). This finding supports H3b. However, the second half of the hypothesis was not supported. No significant differences χ2 (1, N = 14) = 0.286, p > 0.001 were found between males and females in outdoor settings. The male–female ratio was 60% to 40% in outdoor settings.

To test H4a, which stated that more females than males will be depicted in Indian television advertisements for home and household products, a chi-square analysis was performed. The results found significant differences χ2 (1, N = 108) =37.32, p < 0.001 between male and female portrayal in ads for home and household products. Females were shown in advertisements for home and household products significantly more frequently (80%) than males (20%). This finding supports H4a.

To test H4b, which stated that more males than females will be associated with the advertisements for banking and technology, development, healthcare, and transportation in Indian television advertisements, a chi-square analysis was performed for each category. The results found significant differences

χ2 (1,

N = 108) = 19.84,

p < 0.001 in banking and technology category;

χ2 (1,

N = 108) = 10.17,

p < 0.001 in the development category; and

χ2 (1,

N = 108) = 10.52,

p < 0.001 in the transportation category between male and female portrayal. In the banking and technology, development, and transportation categories, males (95.70%, 100%, and 93.30%, respectively) were depicted significantly more frequently than females (4.30%, 0%, and 6.70%, respectively). However, the hypothesis was not supported in the healthcare category. No significant differences

χ2 (1,

N = 108) = 3.06,

p > 0.001 were found between males and females in this category of advertisement, which led to H4b being partially supported. To better illustrate the key gender-related findings of the content analysis, as shown in

Figure 2, gender distribution in Indian television advertisements (2011–2020) reveals that men were predominantly featured in workplace, transportation, and technology settings, while women were more visible in home settings and household product categories.

Figure 2 also highlights the stark imbalance in voiceover roles, where male dominance is evident.

7. Discussion

Empirical evidence and studies suggest that the stereotypical portrayals of gender are widespread in television advertisements (

Eisend, 2010;

Furnham & Mak, 1999;

Ganahl et al., 2003;

Matthes et al., 2016). Gender stereotyping is ubiquitous in Indian television advertisements as well, and a byproduct of such stereotyping is the increasing cultural pressure on women to represent themselves and behave in a certain way in real life (

Sarkar, 2015). As

Prabhash (

2005) put it, media can function both as a mechanism of social control and as a tool for manufacturing public consent. Its significant influence in shaping and reflecting societal realities enables it to sway public opinion and garner support for specific social, political or ideological agendas. In the context of India, most existing studies on television advertisements have either focused solely on the portrayal of women or employed qualitative methods. This study contributes to the field by offering a decade-long, quantitative analysis of gender portrayal in Indian TV commercials, encompassing both male and female representations. Rather than showing a shift toward gender parity, the findings reveal that male representation still outweighs female representation, suggesting a continued reinforcement of gender hierarchies in televised advertising content.

Numerical representation and product categories will be discussed together because the former leads to the latter. There is a connection between Hofstede’s Masculinity Score and numerical representation of male characters’ predominance over female characters (

Milner & Collins, 2000). These findings support prior studies. There was a significant difference between male and female representation in Indian television commercials and each gender’s association with certain product categories. Traditional gender norms and assumptions that portray males as the main breadwinners and decision-makers and women in caregiving roles (

Das, 2010) have long shaped Indian society. Due to these prejudices, male protagonists who exude prosperity, authority, or leadership are frequently preferred in TVCs. Additionally, family values and relationships are highly valued in Indian culture (

Das, 2010). As per Hofstede’s Cultural Dimension (

Hofstede, 2001), India is a high-power distance culture with a score of 72. Such power distance is reflected in the frequencies of gender representations in TVCs. A big reason behind males outnumbering females as the primary characters could be, as

Neale et al. (

2015) argued, that both male and female customers equally accept products and brands associated with or endorsed by males. But males have a rejection tendency towards feminine products or brands that target females: for example, a car that targets the female base (

Neale et al., 2015). This could be a reason why advertisers recruit more male models than female models as primary characters.

The predominance of male characters in Indian TVCs leads to the next part of the discussion, which is product categories. This study reveals significant differences in the portrayal of gender across product categories. Women are heavily featured in the advertisements of home/household product categories such as toiletries, cleaning, cooking products, etc. The rest of the categories, such as banking, technology, transportation, and development, are heavily dominated by men, and women are notably underrepresented. Even though in health categories, women outnumbered men as primary characters, they are mainly shown as either moms who are concerned about the health of their family members or as housewives who get body aches due to doing chores all the time, instead of being shown in high-status roles such as medical professionals. According to Gender bias & inclusion in advertising in India (

Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media and UNICEF, 2021), women only represent 11% of workers in healthcare. Hence, the number of women outnumbering men in the health category of advertisements was unexpected.

The reason behind such stereotypical representations in product categories could be, as

Wolf (

2009) suggested, that the expression of modern feminism works differently in India. Indian women view equality as something family-centered instead of individual-centered, and still, they prioritize family and value their roles at home. That is why it is believed that household products will draw more consumers if females market them in television commercials as primary characters. By doing so, these advertisements uphold traditional gender roles for women in society. Product categories such as banking and technology, development, and transportation overall showed significant differences between male and female representation because these industries have historically been male-dominated. The quote, “Home and childcare taste sweeter to women while business and profession taste sweeter to men,” has long enjoyed unquestioning social acceptance in Indian society (

Sivakumar & Manimekalai, 2021). In India, males are socially raised in ways that prepare them for management and leadership roles characterized by competitiveness, aggression, and risk-taking behaviors (

Sivakumar & Manimekalai, 2021).

Categories such as health and development were not found to be used by previous studies conducted with similar methods; hence, comparison was not possible. However, this speaks for the novel value of the present findings.

Regarding voiceovers, as

Paek et al. (

2010) showed, there is a connection between a higher masculinity rate and a higher number of male voiceovers, and that trend is more prevalent in Asia and Africa (

Furnham & Mak, 1999;

Grau & Zotos, 2016). Also, in this study, it was noticed that there is a close association between the gender of the primary characters in the TVCs and voiceovers (

Eisend, 2010;

Paek et al., 2010). The number of male primary characters is higher in almost every product category, apart from the home, household, and health products. That is the reason the number of male voiceovers is significantly higher than the number of female voiceovers. One reason behind this could be because male voice is often associated with authority (

McArthur & Resko, 1975;

Silverstein & Silverstein, 1974).

When it came to character settings, prior works have found women in home settings (

Furnham & Paltzer, 2010;

Das, 2010) and men in workplace settings (

Prieler & Centeno, 2013), and some studies found men used in outdoor settings more frequently than women (

Prieler & Centeno, 2013;

Furnham & Voli, 1989;

Milner & Higgs, 2004;

Valls-Fernández & Martínez-Vicente, 2007). The cultural norms in India dictate that women should be modest and reserved. As discussed in this study several times, Indian society is mostly traditional. Hence, advertisements portray women in a home setting to create a benchmark for the ideal Indian woman who is devoted to her family and the homemaker role.

Like many other patriarchal societies, there are still disparities in the labor force (

Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media and UNICEF, 2021), working environment, and pay rates between men and women (

Dutta, 2017). Historically, too, there have been limited opportunities for women. However, this study did not find significant differences between men and women in outdoor settings, probably because technological and generational change is occurring along with change in consumers’ tastes and lifestyles.

These findings can be further understood through the lens of cultivation theory and framing theory, which guided the theoretical framework of this study. Cultivation theory suggests (

Gerbner & Gross, 1976) that repeated exposure to similar media messages over time can shape viewers’ perceptions of reality. In this study’s case, the persistent portrayal of women in domestic settings and caregiving roles, and men in positions of authority and professional spaces, may contribute to the normalization of these gender roles in society. Framing theory (

Goffman, 1974;

Entman, 1993) helps explain how these portrayals are constructed—through selective use of visuals, voiceover, settings, and roles that highlight traditional gendered expectations. These theoretical perspectives clarify the symbolic and structural strategies used by advertisers to align with dominant culture norms, thereby reinforcing gender hierarchies in Indian media narratives.