From Victim to Activist: The Portrayals of Ukrainian Refugee Women in Gazeta Wyborcza and Rzeczpospolita During the Full-Scale Russian Invasion of Ukraine (2022–2025)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Representation of Refugee Women in the Media: A Global Overview

2.2. Media Representations of Refugees in Poland

3. Materials and Methods

- RQ1. How are Ukrainian refugee women portrayed in Gazeta Wyborcza and Rzeczpospolita over the three years of the Russian–Ukrainian war, and are these portrayals shaped by gender-based or national stereotypes?

- RQ2. Has the media representation of Ukrainian female refugees changed over time, and if so, how do these shifts correlate with key political or humanitarian events?

- RQ3. To what extent do Gazeta Wyborcza and Rzeczpospolita contribute to shaping public perception through their portrayals of Ukrainian refugee women?

- RQ4. What external affairs (e.g., policy decisions, public debates, EU responses) have influenced the coverage of Ukrainian women refugees in these leading Polish newspapers?

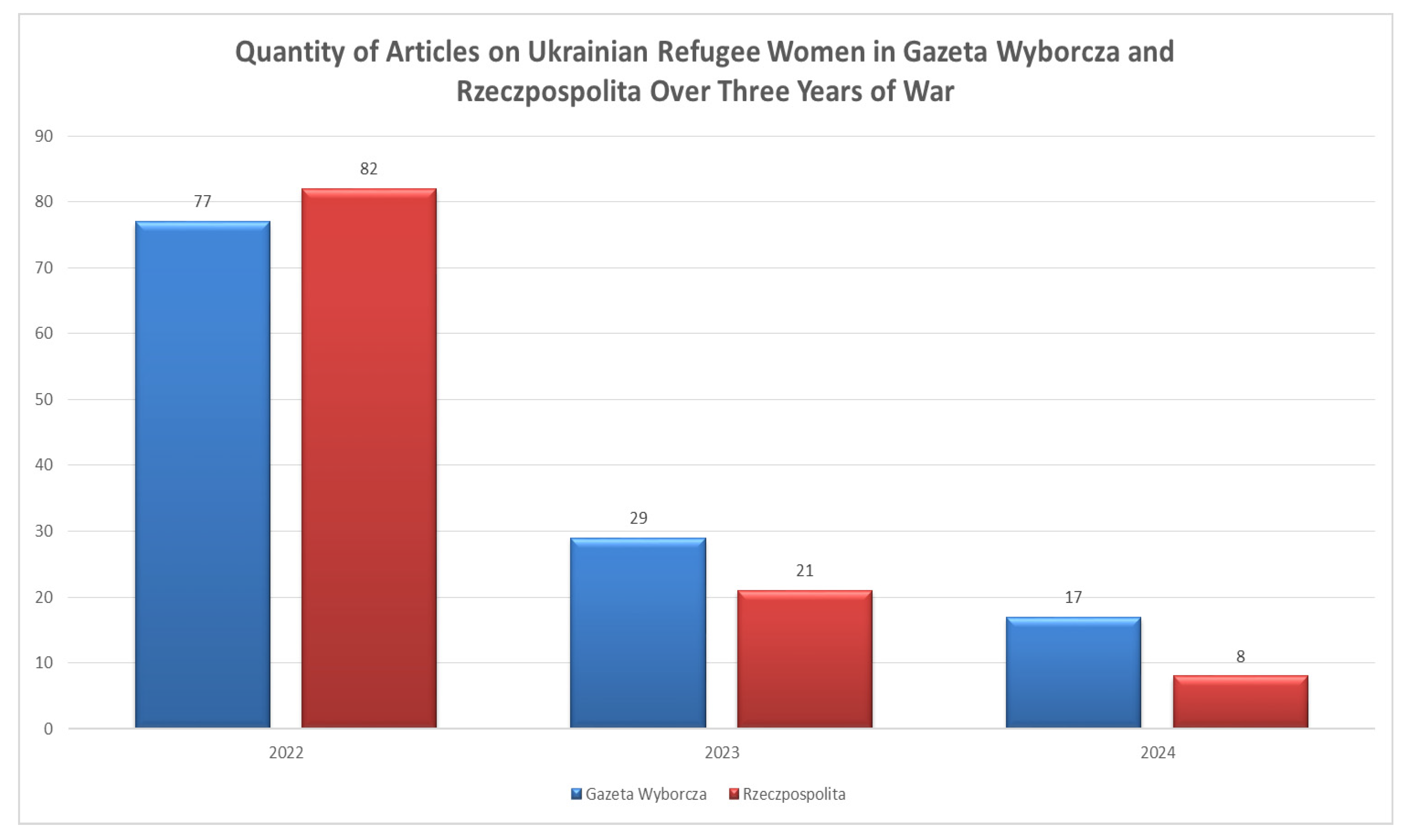

4. Results

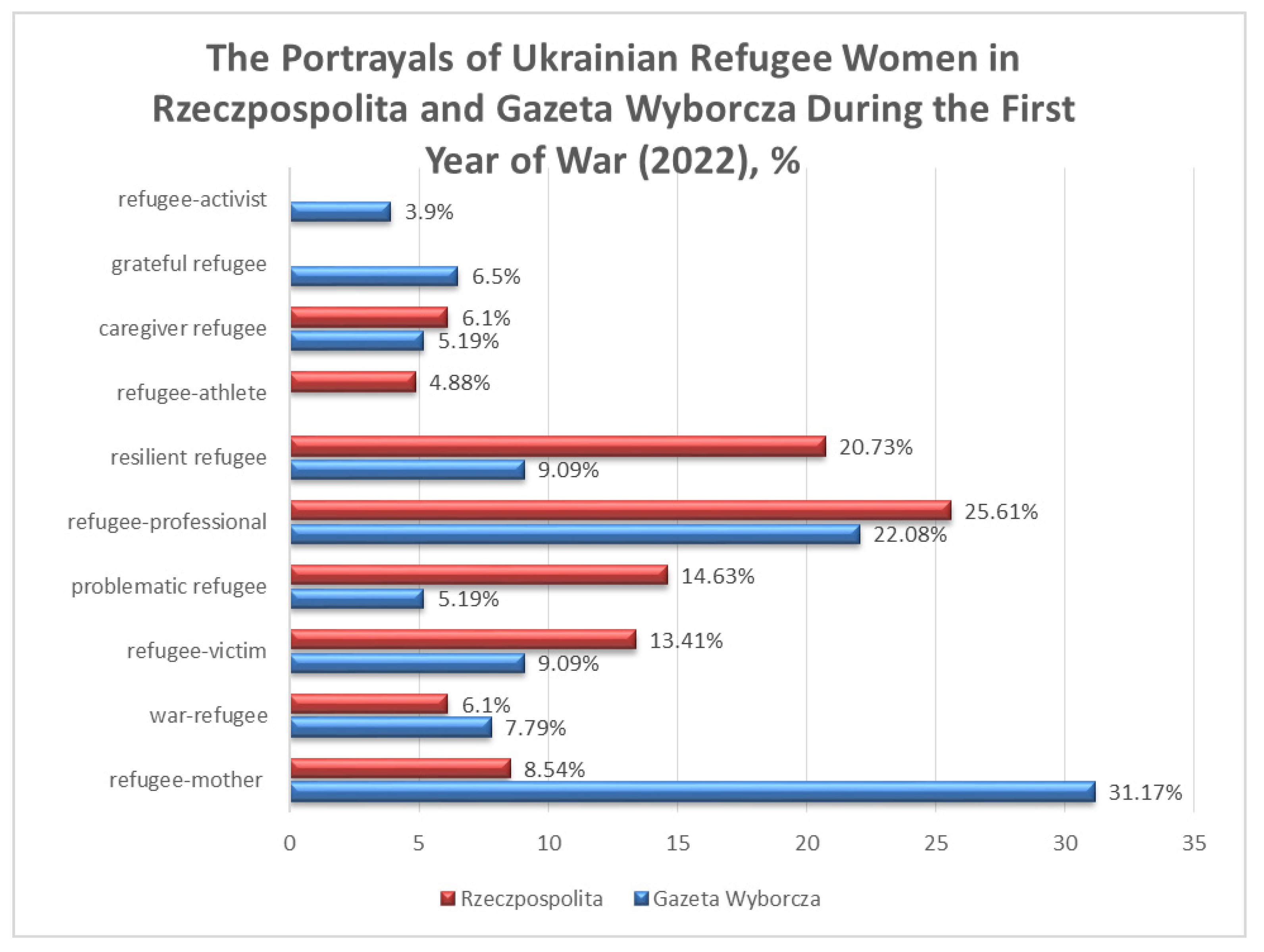

4.1. Rzeczpospolita

4.2. Gazeta Wyborcza

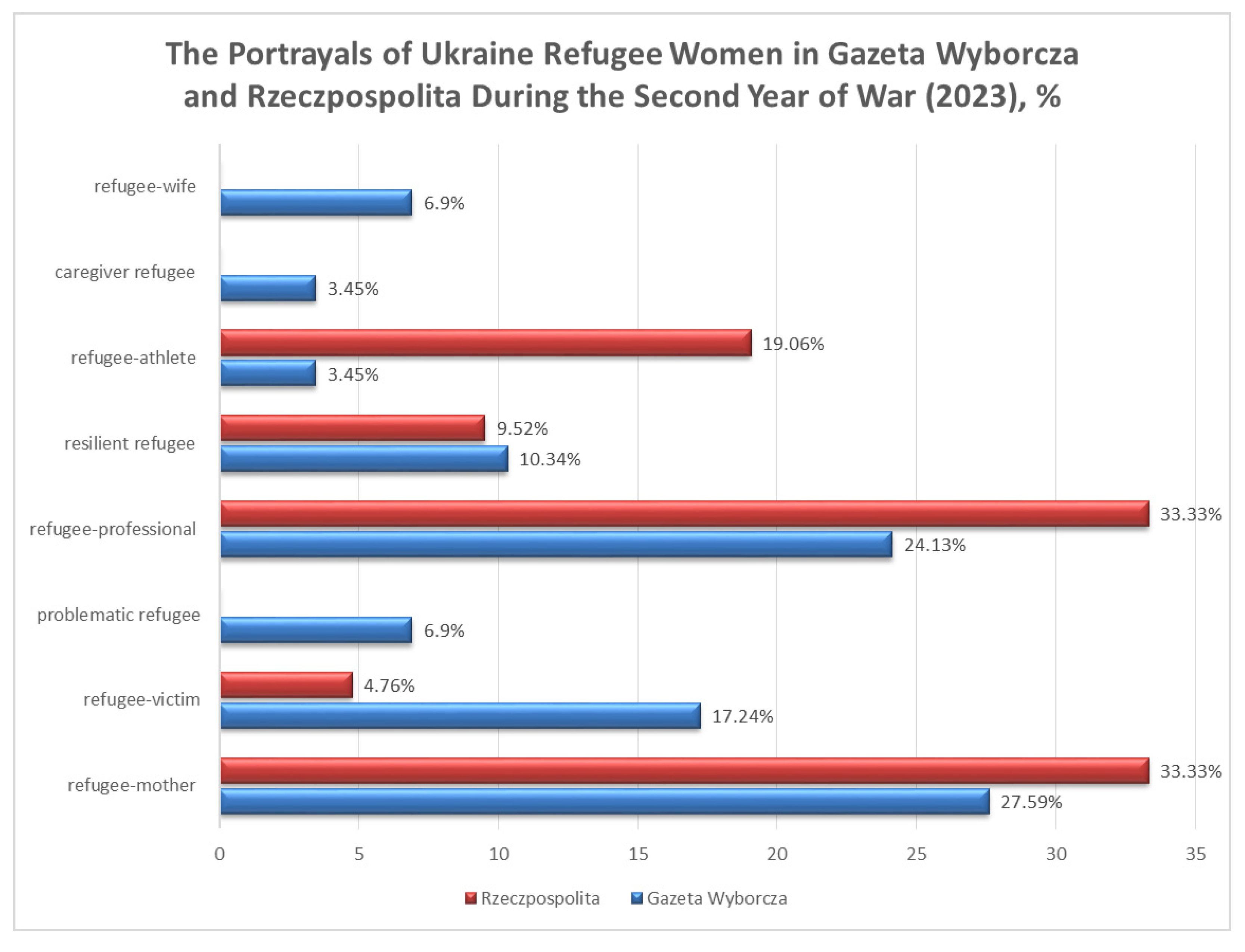

4.3. Between Motherhood, Trauma, and Professionalism: Ukrainian Refugee Women in 2023–Early 2024 Media Narratives

“My husband and I have never been apart for so long. The loneliness worries me a lot. He called and said he had two days off, so I am packing and flying to him. It is written that I might lose my refugee status, but for me, hugs and touch are more important…”

(orig. „Mój mąż i ja nigdy wcześniej nie byliśmy rozdzieleni na tak długo…”)

“I don’t understand why Russian athletes should compete. Russians do not value human life; they kill us. Many Russian sportsmen are also military personnel…”

(orig. „Nie rozumiem, dlaczego rosyjscy sportowcy mieliby mieć prawo do udziału…”)

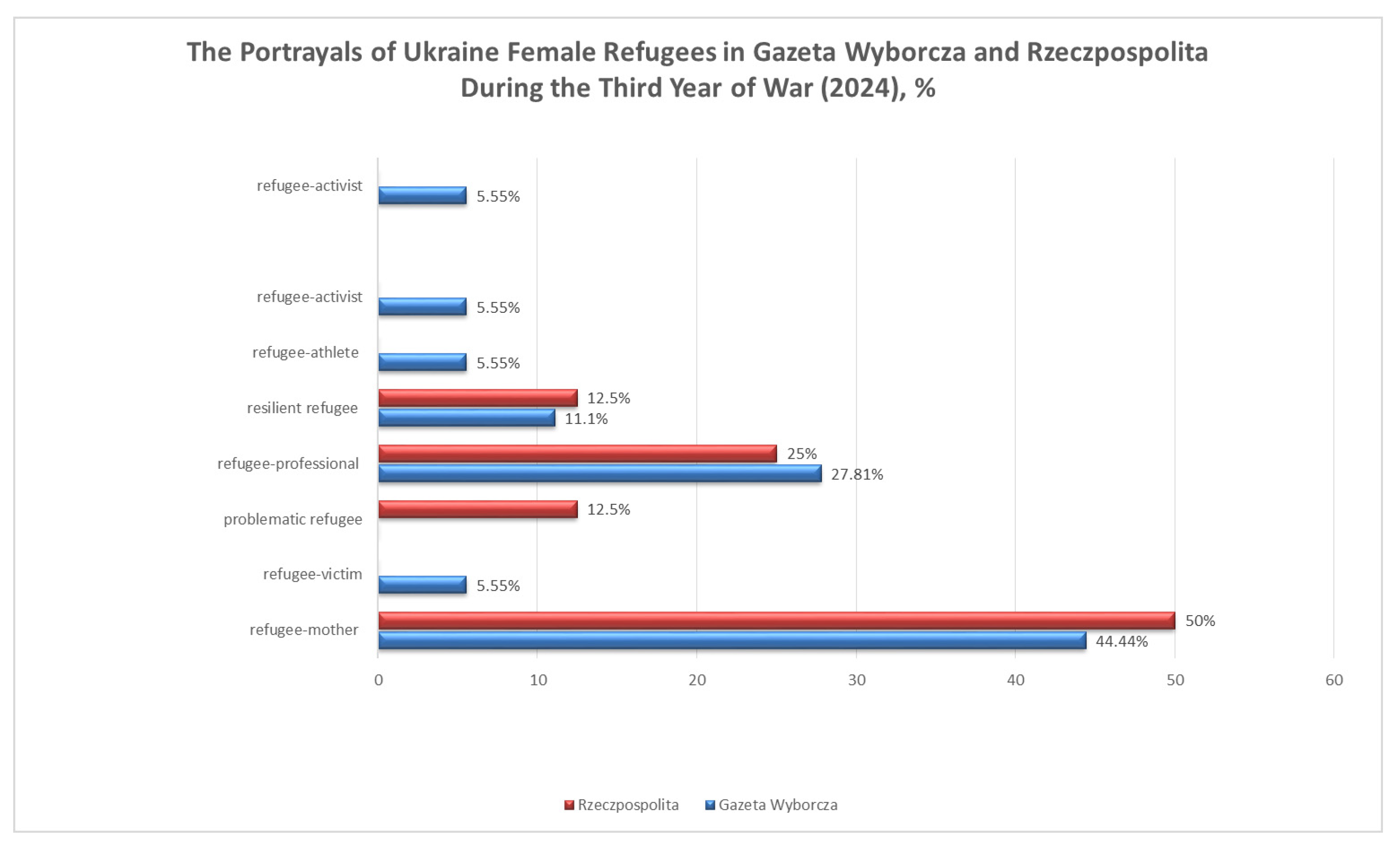

4.4. Shifting Perceptions of Ukrainian Refugee Women in the Third Year of the War

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ager, A., & Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. Journal of Refugee Studies, 21(2), 166–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, C., Pérez, M. H., & Stitteneder, T. (2021). The integration challenges of refugee women and migrants: Where do we stand? CESifo Forum, 22(2), 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Aldamen, Y. (2023). How the media agenda contributes to cultivating symbolic annihilation and gender-based stigmatization frames for Syrian refugee women. Language, Discourse & Society, 11(2), 98–116. [Google Scholar]

- Amores, J. J., Arcila-Calderón, C., & González-de-Garay, B. (2020). The gendered representation of refugees using visual frames in the main Western European media. Gender Issues, 37(4), 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrusleczko, P. (2022, June 24). Ukraińcy chcą swojego kraju w Unii [Ukrainians want their country in the EU]. Gazeta Wyborcza. Available online: https://wyborcza.pl/7,75399,28615037,prawie-90-proc-ukraincow-chce-swojego-kraju-w-ue-jak-rzad.html (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid modernity. Polity Press. ISBN 0745624103. [Google Scholar]

- Beauvoir, S. D. (1949). The second sex (H. M. Parshley, Trans.). Gallimard. ISBN 978-0307277787. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, M. (2021). Women refugees’ media usage: Overcoming information precarity in Germany. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 20(1), 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, A., & Collier, P. (2017). Refuge: Rethinking refugee policy in a changing world. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biesiada, A., Mastalerz-Migas, A., & Babicki, M. (2023). Response to provide key health services to Ukrainian refugees: The overview and implementation studies. Social Science & Medicine, 334, 116221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, W., & Jaworsky, B. N. (2018). Refugees as icons: Culture and iconic representation. Sociology Compass, 12(3), e12568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleiker, R., Campbell, D., Hutchison, E., & Nicholson, X. (2013). The visual dehumanisation of refugees. Australian Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, N. (2023). Is a woman a better refugee than a man? Gender representations of refugees in the Polish public debate. Studia Migracyjne-Przegląd Polonijny, 3(189), 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Braniewicz, E. (2022, September 27). Skąd niechęć do Ukraińców? [Where does the resentment toward Ukrainians come from?]. Gazeta Wyborcza. Available online: https://wyborcza.pl/7,75398,31688884,cbos-po-raz-pierwszy-od-lat-wiecej-polakow-deklaruje-niechec.html (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge. ISBN 9780415900423. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño, F. J. G., Fernandez, A. C., & Martínez, A. G. (2021). The media representation of refugee women in Spain: The humanitarian crisis of the first refugee women in the press. In Handbook of research on promoting social justice for immigrants and refugees through active citizenship and intercultural education (pp. 98–128). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- CBOS. (2022). Komu ufają Polacy? Zaufanie do mediów i instytucji publicznych. Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2022/K_070_22.PDF (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. (2022). Stosunek polaków do uchodźców z Ukrainy [Poles’ attitudes toward Ukrainian refugees]. CBOS. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/EN/publications/news/2022/10/newsletter.php (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Cheshmedzhieva-Stoycheva, D. (2017). The image of the refugee: Real and imagined (Based on examples from the Bulgarian and the British media). Science and Education a New Dimension. Humanities and Social Sciences, 22(131), 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chugaievska, S. (2025). Ukrainian refugees’ adaptation to and integration with new societies and communities in the context of migration policy management. Wiadomości Statystyczne. The Polish Statistician, 70(3), 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćwiek, J. (2022, April 13). Uchodźcy z dyplomami [Refugees with diplomas]. Rzeczpospolita. Available online: https://www.rp.pl/spoleczenstwo/art36063581-uchodzcy-z-ukrainy-z-dyplomami (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Cylka Kłopotowski. (2022, April 11). Czas na sprzatanie [Time for cleanup]. Gazeta Wyborcza. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowska, A. (2024, September 1). Jak sprawić, by imigranci stali się sąsiadami Polaków? [How to make immigrants become neighbors of Poles?]. Rzeczpospolita. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowska, Z. (2022, October 25). Czy domknie się piekło kobiet? [Will the hell of women close?]. Rzeczpospolita. Available online: https://www.rp.pl (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Długosz, P. (2023). War trauma and strategies for coping with stress among Ukrainian refugees staying in Poland. Journal of Migration and Health, 8, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długosz, P. (2024). Ukrainian War Refugees in Poland. In Humanity and Ukraine: Resistance through Language, Culture, and the Taking Up of Arms (119 Publisher: Lexington Books). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-66696-052-5. [Google Scholar]

- Domagała, M. (2022, February 28). Punkt, w którym wszystko zaczyna się od nowa [The point at which everything begins anew]. Gazeta Wyborcza. [Google Scholar]

- Duszczyk, M. (2022, April 19). Ukrainki zadbają o nasze zdrowie [Ukrainian women take care of our health]. Rzeczpospolita. [Google Scholar]

- Duszczyk, M., & Matuszczyk, K. (2014). Migration in the 21st century: Polish perspective. Ośrodek Badań nad Migracjami. [Google Scholar]

- Esses, V. M., Medianu, S., & Lawson, A. S. (2013). Uncertainty, threat, and the role of media in promoting the dehumanization of immigrants and refugees. Journal of Social Issues, 69(3), 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassin, D. (2011). Humanitarian reason: A moral history of the present. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fedyuk, O. (2012). Images of transnational motherhood: The role of photographs in measuring time and maintaining connections between Ukrainian migrant mothers and children left behind. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38(2), 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbner, G. (1976). Living with television: The violence profile. Journal of Communication, 26(2), 173–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goban-Klas, T. (2024). Technologie medialne w rozwoju człowieka i cywilizacji (345p). TAiWPN Universitas. [Google Scholar]

- Gorlicka, M. (2023, March 27). Reżyserka „Matki. Piosenka na czas wojny” o kobietach, które przeżyły terror w Ukrainie i Białorusi [Director of “Mother. A Song for Wartime” about women who survived terror in Ukraine and Belarus]. Rzeczpospolita. [Google Scholar]

- Górny, A., Kaczmarczyk, P., & Szulecka, M. (2018). Imigranci w Polsce—Skala, struktura i znaczenie dla rynku pracy. NBP. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, A. S., Olimy, S. S., & Al-Abbas, L. S. (2021). Media coverage of Syrian refugee women in Jordan and Lebanon. Sage Open, 11(1), 2158244021994811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Sage Publications. ISBN 978-0761954323. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, M., & Sitek, M. (2023). Education in exile: Ukrainian refugee students in the schooling system in Poland following the Russian–Ukrainian war. European Journal of Education, 58(4), 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestermann, T. (2018). Refugees and migrants in the media: The black hole. In H. Kury, & S. Redo (Eds.), Refugees and migrants in law and policy (pp. 102–115). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Himmel, R., & Baptista, M. M. (2020). Migrants, refugees and othering: Constructing Europeanness. An exploration of Portuguese and German media. Comunicação e Sociedade, (38), 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglicka, K. (2001). Migration movements from and into Poland in the light of East–West European migration. International Migration, 39(1), 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMM. (2024, October 22). Gazeta Wyborcza opiniotwórczym liderem, w czołówce również Rzeczpospolita i Onet. IMM. Available online: https://www.imm.com.pl/baza-wiedzy/aktualnosci/gazeta-wyborcza-opiniotworczym-liderem-w-czolowce-rowniez-rzeczpospolita-i-onet/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Inpoland. (2025, June 13). Дo якoї країни найчастіше їдуть українці у 2025 рoці? Це не Пoльща [Which country do Ukrainians most often go to in 2025? It’s not Poland]. InPoland.net.pl. Available online: https://inpoland.net.pl/novosti/do-yako%D1%97-kra%D1%97ni-najjchastishe-%D1%97dut-ukra%D1%97nci-u-2025-roci-ce-ne-polshha/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Jaroszewicz, M., & Szeptycki, A. (2023, November 21). Polska i ukraina potrzebują uchodźców. MSN Polska. Available online: https://www.msn.com/pl-pl/wiadomosci/other/marta-jaroszewicz-andrzej-szeptycki-i-polska-i-ukraina-potrzebuj%C4%85-uchod%C5%BAc%C3%B3w/ar-AA1kgfAE (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Johnson, H. L. (2011). Click to donate: Visual images, constructing victims and imagining the female refugee. Third World Quarterly, 32(6), 1015–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzak, I. (2022, September 19). Tęsknota za krajem ważniejsza od wojny [Nostalgia for the homeland is more important than the war]. Rzeczpospolita. [Google Scholar]

- Kacprzak, I., & Zawadka, G. (2022, February 28). Przybywa uciekających [More and more are fleeing]. Rzeczpospolita. [Google Scholar]

- Karwowska. (2023, January 12). Bardzo wiele z tego co miałam przed wojną już nie istnieje [A lot of those I had doesn’t exist anymore]. Wyborcza.pl. Available online: https://wyborcza.pl/7,162657,29342999,bardzo-wiele-z-tego-co-mialam-przed-wojna-juz-nie-istnieje.html (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Kindler, M. (2011). A risky business? Ukrainian migrant women in Warsaw’s domestic work sector. Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kindler, M., & Szulecka, M. (2013). The economic integration of Ukrainian and Vietnamese migrants in the Polish labour market. International Migration, 51(1), 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindziuk, M. (2022). Polish public on the Ukrainian refugees in the first month of the Russian–Ukrainian war in the “Polityka” and “Gość Niedzielny” weeklies: Research report. Roczniki Nauk Społecznych. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klochko, P. (2023). The dynamics of liberal media discourse on the Middle Eastern migration crises: The case of Gazeta Wyborcza in 2015 and 2021 [Master’s thesis, University of Tartu]. University of Tartu Digital Archive. [Google Scholar]

- Koczanowicz, L. (2023). Moral emotions and the public sphere in Poland: The case of Ukrainian refugees. Social Research, 90(1), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołsut, K. (2023, March 7). Biała flaga we krwi [White flag in the blood]. Rzeczpospolita. [Google Scholar]

- Kubiciel-Lodzińska, S., & Solga, B. (2023). The challenges of integrating Ukrainian economic migrants and refugees in Poland. Intereconomics, 58(6), 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharczyk, J., & Mrozowski, M. (2018). Fear and hope: Polish attitudes toward refugees. Institute of Public Affairs. ISBN 978-83-7689-307-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kulczycka, A. (2022, September 30). Zorganizowane grupy z Ukrainy drenują pomoc [Organized groups from Ukraine are draining aid]. Gazeta Wyborcza. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmuk, O. (2024). Ukrainian refugee women’s experiences in Poland in the first months of Russian invasion: A qualitative account. European Societies, 26(2), 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, P. (2022). Refugees from Ukraine on the Polish labour market. Ubezpieczenia Społeczne. Teoria i Praktyka, 4(155), 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Łódzki, B. (2019). Rola big data w kampaniach wyborczych. Media-Culture-Social Communication, 2(15), 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowska, A., & Vyhovska, T. (2023, June 20). Co gorsze: Strach przed bombami czy tęsknota? [Which is worse: Fear of bombs or longing?]. Gazeta Wyborcza. [Google Scholar]

- Martyniuk, I., & Pelc, I. (2023, January 23). Do wolności przez rosyjski obóz filtracyjny i Moskwę [To freedom through a Russian filtration camp and Moscow]. Gazeta Wyborcza. [Google Scholar]

- McBrien, J. L. (2005). Educational needs and barriers for refugee students in the United States: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 329–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, C. E., Jost, P., Schemer, C., Kruschinski, S., & Maurer, M. (2025). How (gendered) media portrayals of refugees affect attitudes toward immigration: The moderating role of political ideology. Political Communication, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micor, M. (2022, August 29). Grają u siebie [They play at home]. Rzeczpospolita. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual and other pleasures. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780333445297. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, B., Brzóska, P., Piotrowski, J., Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., & Jonason, P. K. (2023). They will (not) deceive us! The role of agentic and communal national narcissism in shaping the attitudes to Ukrainian refugees in Poland. Personality and Individual Differences, 208, 112184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandir, M. (2020). Media portrayals of refugees and their effects on social conflict and social cohesion. PERCEPTIONS: Journal of International Affairs, 25(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Economic Institute. (2023). 80% of refugees from Ukraine see a positive attitude towards them among Poles. Available online: https://pie.net.pl/en/80-of-refugees-from-ukraine-see-a-positive-attitude-towards-them-among-poles/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Polish Economic Institute. (2024). 65% of Ukrainian refugees work, but face many challenges in the Polish labour market. Available online: https://pie.net.pl/en/65-ukrainian-refugees-work-but-face-many-challenges-in-the-polish-labour-market/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Portes, A., & Zhou, M. (1993). The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 530(1), 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Průchová Hrůzová, A. (2021). What is the image of refugees in Central European media? European Journal of Cultural Studies, 24(1), 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radio Svoboda. (2025, July 26). Бaгaтi бiжeнцi, Boлинь тa втoмa вiд вiйни. Гocтpi пoльcькo-yкpaїнcькi тeми: гoвopимo пpo ниx з пocлoм [Wealthy refugees, Volhynia, and war fatigue: Sensitive Polish-Ukrainian topics discussed with the ambassador] [Video]. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0g9aTKUx9jk (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Rebisz, K. (2022, April 19). Już 100 tys. uchodźców znalazło pracę w Polsce [Already 100,000 refugees have found work in Poland]. Rzeczpospolita. [Google Scholar]

- Rochowicz, P. (2022, March 16). Ryzyko handlu ludźmi na granicy z Ukrainą. Rzeczpospolita [The risk of human trafficking on the border with Ukraine]. Rzeczpospolita. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberger, L., & Schmitt, M. (2024). Refugee women in the media—Prevalence, representation, and framing in international media coverage. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 50(16), 3913–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupnik, J. (2022, September 10–11). Ukraina w Unii? [Ukraine in the EU?]. Gazeta Wyborcza. [Google Scholar]

- Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-74067-6. [Google Scholar]

- Slawiński, A. (2022, March 29). Byłam dyrektorką, wezmę każdą pracę [I was a director, I will take any job]. Gazeta Wyborcza. Available online: https://poznan.wyborcza.pl (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Sobczak-Szelc, K., Pachocka, M., Pędziwiatr, K., Szałańska, J., & Szulecka, M. (2023). From reception to integration of asylum seekers and refugees in Poland (p. 256). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępińska, A. (2015). Rola mediów w kształtowaniu opinii publicznej w Polsce: Między informacją a manipulacją. In M. Kolczyński (Ed.), Społeczeństwo obywatelskie w Polsce (pp. 85–102). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman-Hill, C. M. R., Thompson, S. C., Afsar, R., & Hodliffe, T. L. (2011). Changing images of refugees: A comparative analysis of Australian and New Zealand print media 1998−2008. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 9(4), 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczerbiak, A. (2016). A model for democratic transition and European integration? Why Poland matters. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 8(1), 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak-Boczko, J., Gołębiowska, K., & Górny, M. (2023). Who is a ‘true refugee’? Polish political discourse in 2021–2022. Discourse Studies, 25(6), 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troszyński, M. (2021). History and the media. In The politics of memory in Poland and Ukraine: From reconciliation to de-conciliation. Routlege. ISBN 9781032113944. [Google Scholar]

- Ukrinform. (2022, September 27). 90% of refugees from Ukraine will return home. Not immediately…. Available online: https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-ato/3580768-90-bizenciv-z-ukraini-povernetsa-dodomu-zvisno-ne-odrazu.html (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- UNHCR. (2024). Ukraine refugee situation: Operational data portal. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- UNHCR. (2025). Explainer: War in Ukraine—The human cost and humanitarian response. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/news/stories/explainer-war-ukraine-human-cost-and-humanitarian-response (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. (2022, June 15). 83% yкpaїнcькиx бiжeнцiв—жiнки: Koмiтeт з питaнь coцiaльнoї пoлiтики тa зaxиcтy пpaв вeтepaнiв звiтyє пpo cтaн зaxиcтy yкpaїнцiв зa кopдoнoм [83% of Ukrainian refugees are women: Committee on Social Policy and Veterans’ Rights reports on the protection of Ukrainians abroad]. Available online: https://komspip.rada.gov.ua/news/main_news/75346.html (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Verkuyten, M., & Martinovic, B. (2012). Immigrants’ national identification: Meanings, determinants, and consequences. Social Issues and Policy Review, 6(1), 82–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waloch, N. (2023, March 17). Solidarność wygra z przemoca [Solidarity will win over violence] (p. 7). Gazeta Wyborcza. [Google Scholar]

- Wasilewski, J., Osiadło, K., Skorupska, P., & Mordacz, K. (2021). Media narratives on refugees in the Polish press: Narrative analyses. [PDF file]. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351066621_Media_narratives_on_refugees_in_the_Polish_press_-_narrative_analyses (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Wieliński, B. (2024, February 24–25). Nadal jesteśmy rodziną? [Are we still a family?] (p. 2). Gazeta Wyborcza. [Google Scholar]

- Zakrewska, S. (2022, April 4). Kobiety jednoczą siły [Women unite forces]. Gazeta Wyborcza. [Google Scholar]

- Zalas-Kamińska, K. (2020). Przemoc słowna w wizerunku imigranta/uchodźcy w polskich mediach jako narzędzie walki politycznej [Verbal violence in the image of immigrants/refugees in Polish media as a tool of political struggle]. Przemoc w Mediach, 2, 319. [Google Scholar]

- Zawadzka-Paluektau, N. (2023). Ukrainian refugees in Polish press. Discourse and Communication, 17(1), 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyzik, R., Baszczak, Ł., Rozbicka, I., Wielechowski, M., Zyzik, R., Baszczak, Ł., Rozbicka, I., & Wielechowski, M. (2023). Refugees from Ukraine in the Polish labour market: Opportunities and obstacles. Polish Economic Institute. [Google Scholar]

| Stage | Description | Methods/Theories | Newspapers | Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Theoretical Analysis | Review of scholarly literature on refugee and gender representation and the Polish media context | Beauvoir (1949)—social construction of women; Butler (1990)—gender performativity; Hall (1997)—representation; Said (1978)—othering; Bauman (2000)—liquid identity; Gerbner (1976)—cultivation theory, Portes and Zhou (1993), and Ager and Strang (2008)—migration theories | — | — |

| 2. Content Analysis | Analysis of 235 articles on Ukrainian refugee women based on keywords (e.g., “Ukrainian women,” “refugees”) | Qualitative content analysis; coding using NVivo; Deductive and inductive category development (e.g., ‘victim’, ‘mother’, ‘grateful’) | Gazeta Wyborcza, Rzeczpospolita | 24 February 2022–24 February 2025 |

| 3. Representation Mapping | Identification of dominant narrative frames and visual tropes | Narrative framing; performativity; symbolic representation; semiotic analysis | — | — |

| 4. Dynamics of Change | Temporal comparison of refugee portrayal over 3 years | Comparative analysis by year (Y1–Y3); frequency and tone analysis; diachronic coding | — | Year 1, 2, 3 |

| Criterion | Examples/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Attitude | Positive, supportive; neutral, balanced; negative, opposing |

| Narratives | Victimhood, gratitude, motherhood, economic contribution, successful integration |

| Descriptors | Tired, caring, dependent, hard-working, skilled, educated |

| Stereotypes | Mother, caregiver, victim, threat, freeloader |

| Visuals | Images of women with children, in workplaces, protesting, or receiving aid |

| Sources | Journalists, local officials, NGO workers, refugee women themselves |

| Theories Used | Beauvoir (1949), Butler (1990), Mulvey (1975), Hall (1997), Said (1978), Gerbner (1976), Bauman (2000) |

| Coding Software | NVivo—used for organizing and analyzing qualitative data |

| Portrayal | Rzeczpospolita | Gazeta Wyborcza | Example Article |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refugee Mother | Most common; early reports focused on mothers; positive attitude; emotional imagery | Most common; emotional tone; children-centered stories | Kacprzak and Zawadka (2022) Kacprzak, I., & Zawadka, G. (2022, February 28). Przybywa uciekających [More and more are fleeing]. Rzeczpospolita. |

| War Refugee | Informative, statistical focus; neutral attitude | Informational; data-driven; aimed at breaking stereotypes | Domagała (2022) Domagała, M. (2022, February 28). Punkt, w którym wszystko zaczyna się od nowa [The point at which everything begins anew]. Gazeta Wyborcza. |

| Refugee Victim | Highlighted psychological aid, trafficking threats; neutral attitude | Psychological trauma, war trauma; emotionally charged | Martyniuk and Pelc (2023) Martyniuk, I., & Pelc, I. (2023, January 23). Do wolności przez rosyjski obóz filtracyjny i Moskwę [To freedom through a Russian filtration camp and Moscow]. Gazeta Wyborcza. |

| Problematic Refugee | Negative/neutral; focused on aid abuse or illegal work | Fewer cases; negative attitude in select brief articles | Kulczycka (2022) Kulczycka, A. (2022, September 30). Zorganizowane grupy z Ukrainy drenują pomoc [Organized groups from Ukraine are draining aid]. Gazeta Wyborcza. |

| Refugee Professional | Most extensive; positive attitude; highly educated women; entrepreneurs | Similar tone; educated women ready for any job | Ćwiek (2022) Ćwiek, J. (2022, April 13). Uchodźcy z dyplomami [Refugees with diplomas]. Rzeczpospolita. |

| Resilient Refugee | Positive; women learning Polish, finding jobs | Positive attitude; stories of adaptation and endurance | Rebisz (2022) Rebisz, K. (2022, April 19). Już 100 tys. uchodźców znalazło pracę w Polsce [Already 100,000 refugees have found work in Poland]. Rzeczpospolita. |

| Refugee Athlete | Presented positively (e.g., volleyball players) | Not present in Gazeta Wyborcza | Kołsut (2023) Kołsut, K. (2023, March 7). Biała flaga we krwi [White flag in the blood]. Rzeczpospolita. |

| Caregiver Refugee | Women caring for elderly, pets, etc.; neutral attitude | Focus on volunteers and mutual aid; positive attitude | Malinowska and Vyhovska (2023) Malinowska, A., & Vyhovska, T. (2023, June 20). Co gorsze: Strach przed bombami czy tęsknota? [Which is worse: Fear of bombs or longing?]. Gazeta Wyborcza. |

| Grateful Refugee | Not present | New portrayal; Ukrainians helping in gratitude | Slawiński (2022) Slawiński, A. (2022, March 29). Byłam dyrektorką, wezmę każdą pracę [I was a director, I will take any job]. Gazeta Wyborcza. |

| Refugee Activist | Not present | New portrayal; women at rallies and EU events | Zakrewska (2022) Zakrewska, S. (2022, April 4). Kobiety jednoczą siły [Women unite forces]. Gazeta Wyborcza |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kitsa, M. From Victim to Activist: The Portrayals of Ukrainian Refugee Women in Gazeta Wyborcza and Rzeczpospolita During the Full-Scale Russian Invasion of Ukraine (2022–2025). Journal. Media 2025, 6, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040161

Kitsa M. From Victim to Activist: The Portrayals of Ukrainian Refugee Women in Gazeta Wyborcza and Rzeczpospolita During the Full-Scale Russian Invasion of Ukraine (2022–2025). Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(4):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040161

Chicago/Turabian StyleKitsa, Mariana. 2025. "From Victim to Activist: The Portrayals of Ukrainian Refugee Women in Gazeta Wyborcza and Rzeczpospolita During the Full-Scale Russian Invasion of Ukraine (2022–2025)" Journalism and Media 6, no. 4: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040161

APA StyleKitsa, M. (2025). From Victim to Activist: The Portrayals of Ukrainian Refugee Women in Gazeta Wyborcza and Rzeczpospolita During the Full-Scale Russian Invasion of Ukraine (2022–2025). Journalism and Media, 6(4), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040161