The New Kids on the Block: Cyberpolitics and the Emergence of New Latin American Parties (2000–2024)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Technological Revolutions in Political Communication

2.2. Digital Political Communication, Segmentation, and Disintermediation

2.3. The Emergence of Digital Parties

2.4. The Role of Microtargeting and Big Data in Electoral Strategies

2.5. Party Fragmentation and New Political Dynamics

3. Methods and Hypothesis

- Internet penetration rates as a proxy for technological adoption.

- Emergence of political parties with parliamentary representation.

- Contextual political milestones.

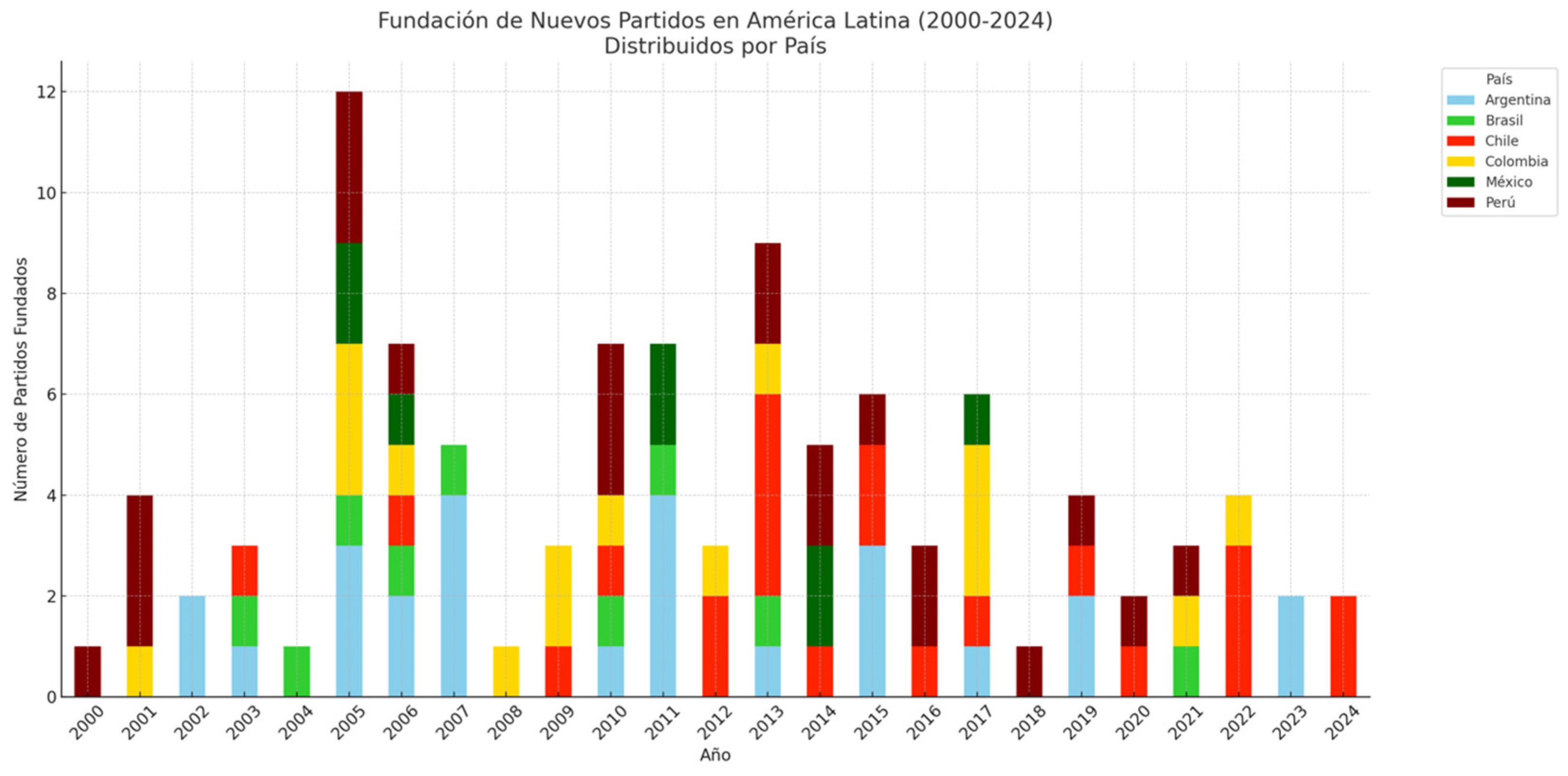

4. Results: The New Kids on the Block—Inventory of New Parties

4.1. Internet Growth

4.2. Emergence of Political Parties with Parliamentary Representation

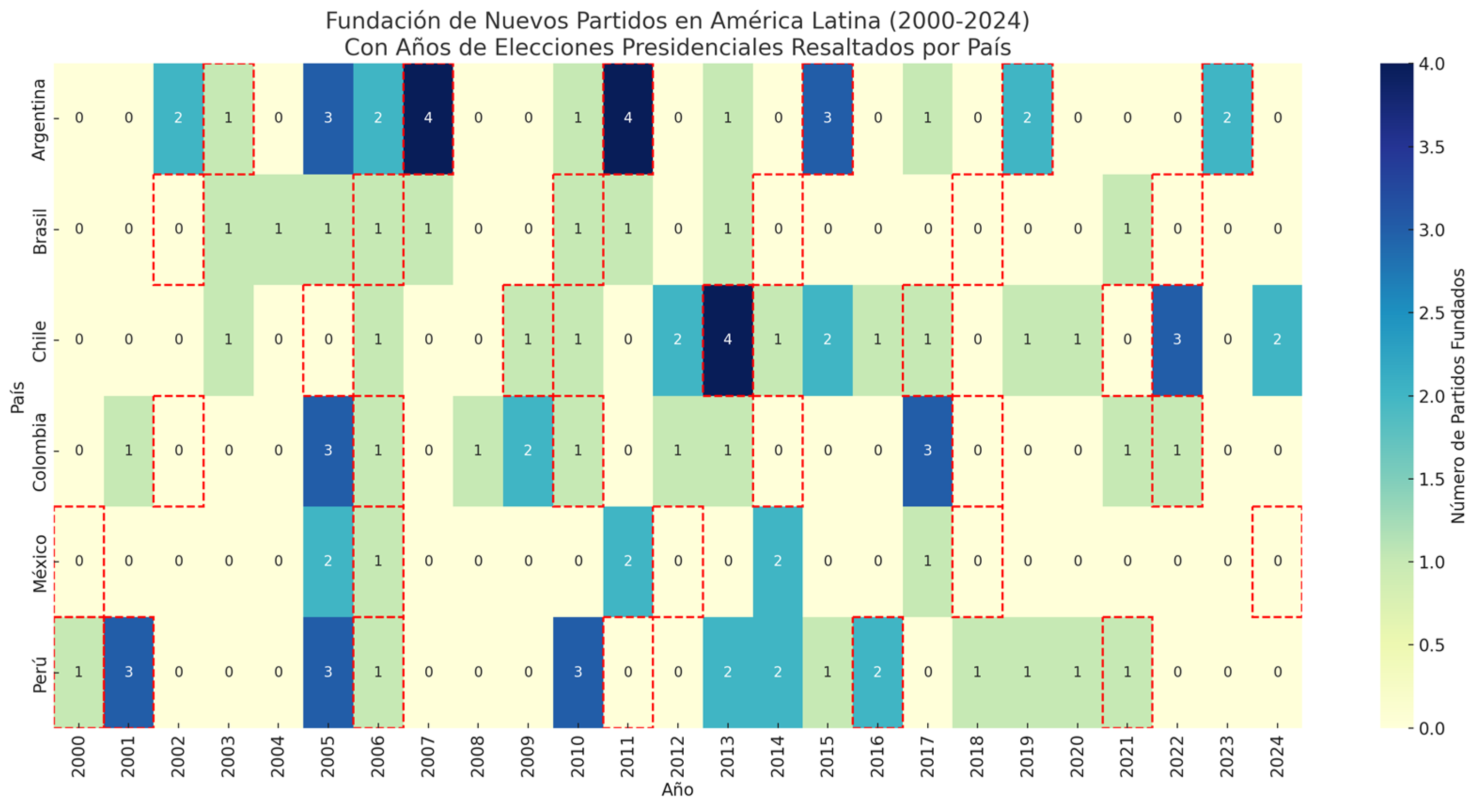

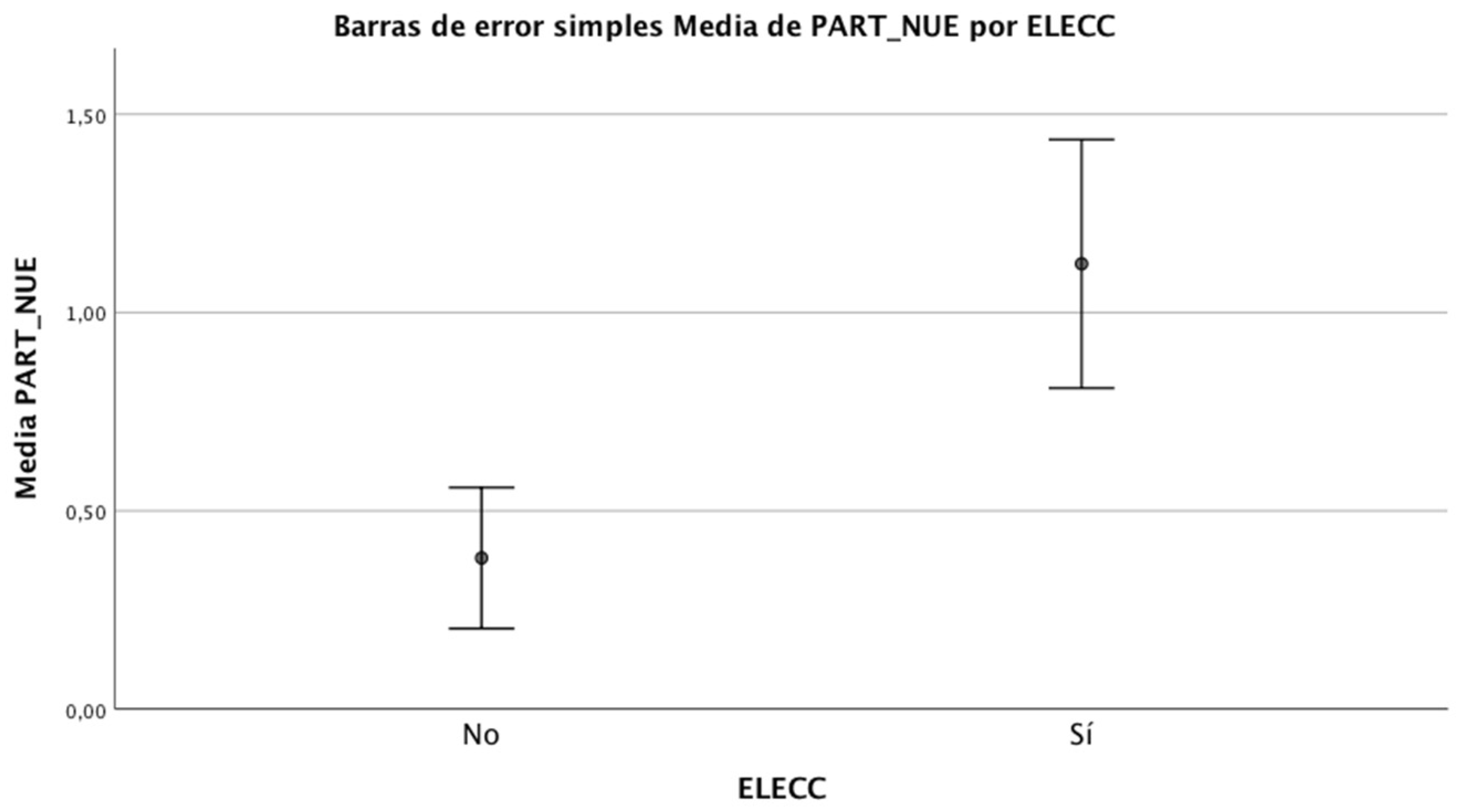

4.3. New Parties and Electoral Milestones

5. Discussion

5.1. Parties and Electoral Cycles

5.2. Segmentation and Fragmentation

- i.

- The ability to target specific segments of the electorate through precise audience definition, including hyper-segmentation.

- ii.

- The opportunity for direct voter engagement, bypassing traditional media and enabling new political communication formats better suited to contemporary communication and marketing languages.

- iii.

- The ease of fostering political organization by building networks of communication, contact, and activism among supporters or allies united by a common cause.

6. Conclusions

- i.

- Impact on Democratic Stability: The relationship between party fragmentation and democratic instability warrants deeper exploration, particularly in contexts of high electoral volatility.

- ii.

- Comparative Analyses: Future research could expand this framework to other regions, examining how cyberpolitics shapes political systems in diverse socio-political environments.

- iii.

- Ethical Considerations on Cyberpolitics: While it was not the main focus of this research, new technological advances in campaigns, such as the use of big data and AI, could be included in contemporary research, as it raises concerns about voter manipulation, privacy, and the transparency of political processes.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | Appendix A in https://docs.google.com/document/d/1qaVf8RvvbGy8ZDrtiu3S1WScYHzUapX5/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=112009112558156647059&rtpof=true&sd=true (accessed on 1 September 2025). |

| 2 | Appendix A can be consulted at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1qaVf8RvvbGy8ZDrtiu3S1WScYHzUapX5/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=112009112558156647059&rtpof=true&sd=true (accessed on 1 September 2025). |

References

- Aldrich, J. (1997). Political parties in a critical era (Vol. 53). Duke University. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, J. (2011). Why parties? A second look. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Amado, A. (2016). Política pop: De líderes populistas a telepresidentes. Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, R. R. (2009). Populists, outsiders and anti-establishment politics. Party Politics, 15(1), 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739–768. [Google Scholar]

- Bodó, B., Helberger, N., & de Vreese, C. H. (2017). Political micro-targeting: A Manchurian candidate or just a dark horse? Internet Policy Review, 6(4), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, W. D., & Sartori, G. (1977). Parties and party systems: A framework for analysis, volume I. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, E., & Aruguete, N. (2020). Fake news, trolls y otros encantos: Cómo funcionan (para bien y para mal) las redes sociales. Siglo XXI Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, A. (2019). The New crisis of public communication (pp. 1–19). Loughborough University. [Google Scholar]

- Chasquetti, D. (2001). Democracia, multipartidismo y coaliciones en América Latina: Evaluando la difícil combinación (pp. 319–359). Clacso. [Google Scholar]

- Choucri, N. (2014). Cyberpolitics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova, L. (2003). Electoral reform and political change in Mexico (pp. 653–703). UNAM. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, R. (1971). Poliarchy. Participation and opposition. Y. U. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, L. (2021). Rebooting democracy, review on Deibert. Journal of Democracy, 32(2), 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. Harper and Row Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, E., & Blank, G. (2018). The echo chamber is overstated: The moderating effect of political interest and diverse media. Information Communication and Society, 21(5), 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C. B. (2008). Cyberpolitics: How do we use digital technologies in Latin American politics? Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, C. B. (2019). Ciberpolítica 2018: Tendencias en Latinoamérica. In Nuevas campañas electorales en América Latina (pp. 147–162). Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. Available online: https://www.kas.de/documents/285099/0/Campa%C3%B1as+electorales+en+Am%C3%A9rica+Latina_WEB.pdf/2467ec17-7309-69e7-80b5-5d2341bd4a23?version=1.0&t=1549986957364 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Fernández, C. B., & Dell’Oro, J. (2011). Campañas políticas exitosas 2.0. Fundación Konrad Adenauer. Available online: https://www.kas.de/es/web/guatemala/einzeltitel/-/content/campanas-politicas-exitosas-2.0 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Fernández, C. B., & Rodríguez-Virgili, J. (2019). Electors are from facebook, political geeks are from twitter: Political information consumption in Argentina, Spain and Venezuela. KOME, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, T. (2006). The world is flat: A brief history of the twenty-first century. International Journal, 61(3), 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbaudo, P. (2014). Populism 2.0: Social media activism, the generic Internet user and interactive direct democracy. In Social media, politics and the state (pp. 67–87). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbaudo, P. (2019). The indignant citizen: Anti-austerity movements in southern Europe and the anti-oligarchic reclaiming of citizenship. In Resisting Austerity (pp. 41–55). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbaudo, P. (2021). Digital parties and their organisational challenges. Ephemera, 21(2), 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks, J. A., Denton, R. J., & Lanham, M. (2010). Communicator-in-Chief: How Barack Obama used new media technology to win the white house. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 40(4), 800–802. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D. (2009). Routledge handbook of political campaigning. In Routledge handbook of Pan-Africanism. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P., & Amstrong, G. (2008). Fundamentos de Marketing. In Expert review of vaccines (Vol. 15). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Latinobarómetro. (2018). 2018 report, survey (p. 82). Latinobarómetro. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Latinobarómetro. (2020). Chile report 2020. Latinobarómetro. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Linz, J. J. (1990). The Virtues of Parliamentarism. Journal of Democracy, 1(4), 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainwaring, S., Brinks, D., & Pérez-Liñán, A. (2001). Classifying political regimes in Latin. Studies in Comparative International Development, 36(1), 37–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi-Sánchez, J. L., Amado-Suárez, A., & Waisbord, S. (2021). Presidential twitter in the face of COVID-19: Between populism and pop politics. Comunicar: Media Education Research Journal, 29(66), 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelsen, A. (2015). Brand Obama: How Barack Obama revolutionized political campaign marketing in the 2008 presidential election. Claremont McKenna College. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Napolitan, J. (1986). 100 cosas que he aprendido en 30 años de trabajo como asesor de campañas electorales. Ponencia presentada en la XIX Asociación Internacional de Asesores Políticos. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Norris, P. (2004). The evolution of election campaigns: Eroding political engagement. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Pippa-Norris-2/publication/228795981_The_evolution_of_election_campaigns_Eroding_political_engagement/links/02bfe511b0ac3d14c7000000/The-evolution-of-election-campaigns-Eroding-political-engagement.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Norris, P. (2024). “Things fall apart, the center cannot hold”: Fractionalized and polarized party systems in Western democracies. European Political Science, 23, 546–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C. (2021). Using the history of technological revolutions to understand the present and shape the future. Available online: https://feps-europe.eu/using-the-history-of-technological-revolutions-to-understand-the-present-and-shape-the-future/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Ratzinger, J. (2011). Truth, proclamation and authenticity of life in the digital age (p. 17). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Rincón, O. (2011). Mucho ciberactivismo… pocos votos. New Society, 235, 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K. M., & Wibbels, E. (1999). Party systems and electoral volatility in Latin America: A test of economic, institutional, and structural explanations. American Political Science Review, 93(3), 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Virgili, J., & Sadaba-Garraza, T. (2010). Electoral advertising: The evolution of electoral spots in Spain (1977–2004). Social Communication. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Rubio Núñez, R. (2018). The effects of post-truth politics on democracy. Revista de Derecho Político, 1(103), 191–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaverría, R. (2005). Cibermedios: El impacto de Internet en los medios de comunicación en España. Comunicación Social Ediciones y Publicaciones. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1943). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. In Modern economic classics-evaluations through time. Routledge. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Serrano-Puche, J., Fernández, C. B., & Rodríguez-Virgili, J. (2018). Political information and incidental exposure on social networks: An analysis of Argentina, Chile, Spain and Mexico. Doxa Comunicación. Interdisciplinary Journal of Communication and Social Sciences Studies, 27, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, J. A., & Nelson, C. J. (1996). Campaigns and elections American style (pp. 1–353). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torcal, M. (2003). Political disaffection and democratization. Available online: https://kellogg.nd.edu/publications/workingpapers/WPS/308.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Tufekci, Z. (2018). It’s the (democracy-poisoning) golden age of free speech. Wired, 16(1), 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, S. (2013). Unpacking the use of social media for protest behavior: The roles of information, opinion expression, and activism. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(7), 920–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedel, T. (2006). The idea of electronic democracy: Origins, visions and questions. Parliamentary Affairs, 59(2), 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisbord, S. (2020). Is it valid to attribute political polarization to digital communication? On bubbles, platforms and affective polarization. Saap Journal, 14(2), 249–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisbord, S., & Amado, A. (2017). Populist communication by digital means: Presidential Twitter in Latin America. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1330–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 3 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 26 |

| Brazil | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| Chile | 1 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 22 |

| Colombia | 1 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 16 |

| Mexico | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Peru | 4 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 22 |

| 11 | 28 | 31 | 20 | 13 | 103 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández, C.B. The New Kids on the Block: Cyberpolitics and the Emergence of New Latin American Parties (2000–2024). Journal. Media 2025, 6, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030143

Fernández CB. The New Kids on the Block: Cyberpolitics and the Emergence of New Latin American Parties (2000–2024). Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(3):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030143

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández, Carmen Beatriz. 2025. "The New Kids on the Block: Cyberpolitics and the Emergence of New Latin American Parties (2000–2024)" Journalism and Media 6, no. 3: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030143

APA StyleFernández, C. B. (2025). The New Kids on the Block: Cyberpolitics and the Emergence of New Latin American Parties (2000–2024). Journalism and Media, 6(3), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030143