Abstract

This research explores the resilience of highly educated individuals in Greece to mis- and disinformation, focusing on their news engagement and information verification practices. Despite high levels of awareness and concern about disinformation, the study found that participants exhibited varying levels of news consumption, with only about 57% visiting news websites daily, and a significant portion relying on social media for exposure to false information. The research highlights the gap between participants’ interest in news and their actual engagement with reliable news sources. The results suggest that individuals with higher education may not be immune to disinformation, often underestimating their vulnerability. Notably, the frequency of news consumption was negatively correlated with the use of rigorous fact-checking methods. Moreover, psychological and social factors, such as the desire for social validation and the importance of content, strongly influenced sharing behavior. The study recommends that media literacy campaigns (MLCs) and overall media literacy education (MLE) for this group should address these cognitive biases and social dynamics, emphasizing critical thinking, the use of multiple sources, and the importance of external fact-checking tools.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, discussion about news authenticity has become a debate in which ever more people are participating. Scientific voices argue that the situation has reached its most critical point. Generative artificial intelligence (AI), which enables even individuals with limited expertise to produce and share content, has exacerbated the situation (Bashardoust et al., 2024; Marchal et al., 2024). Thus, disinformation in all its forms has become a global issue that affects societies worldwide (Vosoughi et al., 2018). The phenomenon, defined as “false or misleading information presented as a fact,” can take many forms, from fabricated news articles to multimodal deepfake content and misleading headlines that distort the truth (Vishnupriya et al., 2024).

Indeed, disinformation campaigns that co-occur with critical events, such as elections, wars, or public health crises, can lead to confusion, panic, and even violence as individuals struggle to identify authentic information in a landscape filled with conflicting narratives (Barua et al., 2020; Harris et al., 2024).

The extensive literature describes almost all aspects of the phenomenon and approaches to countering it. It also underscores the urgent need to understand and combat disinformation through more intensive efforts (Vraga & Bode, 2020; Chan et al., 2022). A wide range of researchers and scientists are involved in understanding and addressing the problem, including sociologists, journalists, fact-checkers, psychologists, political scientists, education experts, legal experts, and, finally, technology experts working on algorithmic automation that identifies falsified or false content (Majerczak & Strzelecki, 2022). The goal of the “News verification industry” as described above is to provide individuals with the necessary knowledge, strategies, and tools to ensure that they are not only aware of the phenomenon of online disinformation but also capable of identifying false and counterfeit information.

In this context, a key component of combating disinformation is enhancing media literacy. As Sonia Livingstone (2004) defines it, media literacy involves the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and create media content across various platforms. In the digital age, these competencies are indispensable for the cultivation of a more informed and active public. Building on this foundation, initiatives like the Media Digital Misinformation Observatory (MedDMO), within which the research presented in this paper was conducted, play a significant role in advancing these efforts. Through the development of relevant educational materials and the execution of MLC, MedDMO seeks to equip citizens with the critical thinking skills and the necessary tools to combat misinformation. To achieve the stated goal of MLC with the highest level of success, it is essential to conduct thorough research into the specific audience targeted by each campaign. As Rasi et al. (2019) have observed, media literacy interventions must be tailored to the diverse needs of individuals across the lifespan, using age-appropriate pedagogical strategies, such as interactive activities for children, critical thinking exercises for teens, practical applications for adults, and cognitive support for older adults.

Another critical issue, aside from age, is “education level.” The current state of research is rich with studies that examine the characteristics of individuals who are particularly susceptible to disinformation and conspiracy theories (Douglas et al., 2019; Baptista & Gradim, 2022). A consistent finding across this body of research is that individuals with lower levels of formal education tend to be more vulnerable to such content, particularly when critical thinking and media literacy skills are underdeveloped (Beauvais, 2022). In some cases, the effect of education appears to be so strong that, in a study conducted among students in an English secondary school, it was found that students’ acceptance of disinformation decreased significantly over their 5 years of secondary education (Siani et al., 2024). Without any tendency to underestimate the importance of the findings, it is considered important to approach these data with caution, as numerous real-world examples demonstrate that fabricated news affects people from all educational backgrounds (Waldrop, 2017). In fact, the above is even more important when studies, like this one, seek to provide insights for the implementation of MLC in order to enhance news content verification skills. However, to achieve this effectively, it is crucial for researchers and trainers to remain mindful and avoid reinforcing stereotypical narratives about specific demographic groups. Hence, our central hypothesis, by challenging the assumption that individuals with higher education levels are resilient to disinformation, posits that they may not always recognize their vulnerability to disinformation, and therefore, require advanced media literacy education (MLE) and should consult reliable external sources to better identify, critically assess, and verify news. Consequently, the main goal of this study is to collect insights that will enhance the understanding of this group for the development of tailor-made MLC that is specifically designed to address the unique needs, behaviors, and challenges in the digital landscape.

As a result, the study sample comprises a notable percentage of participants who possess or are in the process of obtaining higher education degrees, including bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral qualifications. This sample selection was strategic, facilitating an exploration of disinformation perception in a context characterized by theoretically advanced education and critical thinking. At this point, it is crucial to recognize that this focus on higher education, specifically master’s and doctoral degrees, constitutes a primary objective of the research; however, as can be understood, this focus introduces a notable limitation in terms of the generalizability of the findings to the broader population.

The paper is organized as follows to enable proper analysis. The literature review explores the issues addressed in this study. First, it discusses people’s relationship with the news through the analysis of phenomena such as “news avoidance,” “news fatigue,” and misinformation. Next, the various factors that contribute to people’s vulnerability to misinformation are examined. Finally, the information verification strategies, which are emerging as the most important assets in the battle against disinformation, are presented. The materials and methods section outlines the methodology and its aims by presenting the research questions, tools for collecting responses, and participants’ profiles. In the analysis section, the methods of data analysis are outlined. The results section analyzes the research findings, which are thoroughly examined in the discussion section. The paper concludes with a section on limitations and future work, which is followed by the paper’s conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. News Interest, News Fatigue, News Avoidance and Disinformation

Investigating the relationship between news interest, news fatigue, news avoidance and disinformation is a significant challenge in the media ecosystem. Picking up the thread from the beginning, “interest in news” refers to the degree of engagement of individuals with current events, which can lead to the consumption of news content (McCombs & Shaw, 1972; Bruns, 2005; Hermida, 2010). However, having a large amount of information does not help increase news interest and instead often leads to “news fatigue” (Lazer et al., 2018). This phenomenon describes the exhaustion or burnout experienced by individuals due to constant exposure to news, terrible news or repetitive news, which has a significant impact on how individuals process and share information (Islam et al., 2020). Therefore, when a person is tired, there are increased possibilities that they might not recognize false information and might then spread it through the digital sphere (Lazer et al., 2018). This phenomenon is particularly evident in social media, where rapid dissemination of information often occurs without proper verification (Nielsen & Graves, 2017). Pulido et al. (2020) further highlights that, in times of crisis, the spread of false information is exacerbated as users exhaust themselves in their efforts to locate reliable sources. This fatigue can lead users to be less willing to evaluate content critically and to rely on familiar sources, often based on the perceived reliability of the source rather than the content itself (Bhati et al., 2022; Sheehy et al., 2024).

However, Chan et al. (2022) present a finding with an optimistic perspective, suggesting that “concern about disinformation” is linked to increased news authentication behaviors, and that “news fatigue” does not significantly affect these behaviors. This finding aligns with previous research that emphasizes the role of concern about disinformation to the possibility of investing more cognitive resources in evaluating the credibility of news and distinguishing trustworthy sources from unreliable ones (Pennycook & Rand, 2019b).

The same applies in the case of the phenomenon of “news avoidance,” which is also associated with overexposure to certain types of content, including misleading or biased stories, and which can lead to cognitive overload or news fatigue, causing people to disengage (Villi et al., 2022). However, while individuals avoid the news, they also engage in news verification behaviors, suggesting that these actions are seen as necessary to verify the credibility of information, even when they feel overwhelmed or fatigued by the volume of news (Chan et al., 2022).

The associations between news interest, news fatigue, news avoidance and disinformation are complex and interrelated. Expanding on this idea, Fitzpatrick (2022) studied several critical factors contributing to news avoidance, such as the emotional toll of constant negative headlines and a lack of trust in mainstream media, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research highlights the importance of restoring trust in journalism by offering more relevant and deeper storytelling. Fitzpatrick (2022) also suggests that news avoidance and news fatigue are not just short-term issues related to the pandemic, but part of a broader trend that challenges the media ecosystem (Katsaounidou et al., 2018). This broader trend, in addition to the above-mentioned phenomena, also includes cognitive functions and socio-psychological factors that influence users’ susceptibility to misleading information, making it essential to fully analyze the situation.

2.2. Human Cognitive and Socio-Psychological Factors Affect Susceptibility to Disinformation

Individuals often have predispositions that make them more vulnerable to disinformation. One key reason many people believe false information is due to the influence of mental shortcuts, particularly confirmation bias, which shapes their thinking (Nyhan & Reifler, 2010; Van Prooijen et al., 2015). As Bhati et al. (2022) also note, fatigue can lead users to rely on familiar sources, often based on the perceived reliability of the source rather than the content itself. Many individuals rely on familiarity when assessing information as a cue for truthfulness. If a story seems familiar or is widely shared among their social circles, it is often accepted without critical evaluation (Pennycook & Rand, 2019b). This makes humans more vulnerable to accepting ideas that match what they already believe, and to ignore or dismiss anything that challenges those ideas. But this is also not a “scientific consensus.” For example, Ecker et al. (2022) argue that people are likely to believe false information that resonates with their political views, while Pennycook and Rand (2021) support the idea that vulnerability to disinformation is primarily driven by cognitive errors and a lack of relevant knowledge rather than political identity.

Another important factor that determines the way people react to the news is emotion. Bakir and McStay (2018) have indicated that emotionally charged stories, especially those that evoke fear or anger, are more likely to be shared and believed. This emotional response is likely to create a sense of urgency or threat in individuals in their attempts to act quickly to override rational assessment of information accuracy (Tandoc et al., 2018).

Cognitively, many individuals lack the necessary skills for critical information evaluation. According to Ecker et al. (2022), when users encounter disinformation, their inability to recognize factual inaccuracies or logical fallacies leads to an uncritical acceptance of false claims. In addition, cognitive overload is a significant factor contributing to the susceptibility to disinformation. Individuals exposed to an excessive amount of information may have trouble in processing and evaluating content, leading to reliance on simplistic heuristics instead of careful reasoning (Pennycook & Rand, 2021). Social dynamics also significantly affect the likelihood of falling victim to fake news. The phenomena of echo chambers and filter bubbles, where individuals interact primarily with like-minded peers, reinforces existing beliefs and fosters disinformation (Ecker et al., 2022). In the opposite direction, an interesting framework providing evidence about the motivation for sharing hostile information (political) online is the “need for chaos” (Petersen et al., 2023). The study examines the “desire to disrupt established systems and create chaos, often to gain social status.” In this context, people share hostile political rumors, which often involve misinformation or low-evidential content, widely through social media.

Building on the idea of sharing hostile political information for social status, another key factor influencing people’s response to disinformation is their social relationships. For example, people are more willing to correct disinformation shared by close friends or family members, as they feel they have a responsibility to help their loved ones. In contrast, correcting disinformation shared by acquaintances or strangers is often avoided due to concerns about conflict (Tandoc, 2019). All of the above demonstrate that disinformation is a highly complex phenomenon, and, as such, the strategies to address it must be equally multifaceted. To equip people with the tools to identify false information, a variety of strategies have been developed, including human, technological, and organizational approaches.

2.3. Information Verification Strategies

A range of strategies has been devised to combat disinformation, encompassing human, technological, and organizational approaches. Disinformation is combated by the “News Verification Industry,” which acts as the first line of defense. Within this industry, fact checkers must assess information, locate false news, and offer validated information to the public. Prominent international examples include Snopes.com1 and Politifact.com,2 which have earned global recognition for their rigorous fact-checking methodologies (Amazeen, 2020). In Greece, key players, such as Ellinika Hoaxes,3 Fact Review,4 Greece Fact Check,5 Check4facts and AFP,6 fight disinformation and enhance public trust in the media not only by verifying claims, but also by educating the public on how to assess the information they encounter online critically.

Another approach gaining ground is technological solutions that aim to automatically detect fake texts, images, video, and audio. Examples of such tools include the Image Verification Assistant,7 (Zampoglou et al., 2016), Media Asset Annotation and Management (MAAM)8 (Schinas et al., 2023), and the InVID9 verification plugin (Teyssou et al., 2017). Hence, a strong framework for combating online disinformation is produced by the application and advancement of automatic false news detection tools, the work of experts in false claims control.

The institutionalization of regulatory frameworks is another important strategy. The Digital Service Act10 (DSA), is a legislative framework designed to regulate digital services and platforms, particularly those that host, distribute, or moderate user-generated content. By imposing stricter regulations on large platforms, the DSA reinforces the EU’s commitment to creating a safer online environment, while promoting the credibility and integrity of the information shared across digital channels (Turillazzi et al., 2023).

Complementing this legislative push is the establishment of the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO) and its fourteen national or multinational hubs, covering all 27 EU member states and Norway.11 These hubs work in collaboration with local fact-checking organizations, journalists, universities, and technology companies to tackle disinformation at the local level. Their efforts include conducting research on the spread of disinformation, creating educational resources to boost technological and digital literacy, and sharing fact checks with a wider audience.

Thus, alongside technological and institutional approaches, digital literacy is a key factor in addressing disinformation. Educating citizens, both young people and adults, in the skills related to critical analysis of the information they receive from the media is necessary. The ability to browse and critically assess internet information is essential not only for the evaluation of news trustworthiness, but also for making educated decisions in daily life. Specifically, research demonstrates that people with higher digital abilities are more likely to engage in a broader range of online opportunities, such as information-seeking and academic tasks, while also being more equipped to assess the authenticity of the content they encounter (Livingstone et al., 2023).

3. Materials and Methods

Based on the preceding analysis, this study aims to explore the news interest, disinformation awareness and verification skills of highly educated individuals in Greece by addressing the following three research questions (RQ):

RQ1. What is the level of concern among highly educated individuals in Greece regarding disinformation, and what key trends, characteristics, and behaviors emerge from their responses related to its perception, impact, and management?

RQ2. How do highly educated individuals in Greece respond to disinformation, and which are their most and least frequently used fact-checking methods related to their level of news engagement?

RQ3. How do psychological, social, and behavioral factors shape the decisions of highly educated individuals in Greece to share news online?

In order to answer the RQs, a questionnaire was developed by the research team of MedDMO based on relevant literature. The questionnaire was fully anonymized, and the potential participants were asked for their consent to participate in the study while having the option to withdraw at any time. The Cronbach’s Alpha test was conducted to check the reliability of the questionnaire (a av. = 0.83) (Giomelakis et al., 2024). The final set of the 19 assessment factors used in the analysis and results is defined and described in Table 1. The table outlines the diverse factors associated with news consumption, disinformation awareness, exposure, and verification techniques and self-perceived motivations of sharing content online, categorized into nominal, binary nominal and ordinal Likert scales.

Table 1.

Definition and description of the 18 assessment factors used in the analysis and results.

Survey Sample Overview

The following analysis provides an overview of the participants (n = 845) who responded the questionnaire distributed through three universities of Greece, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH), Ionian University and the University of Western Macedonia between December 2023 and May 2024. These universities are expanded in three different regions of the Greek territory, covering all three urban, suburban, and rural cases, with quite a uniform distribution concerning the participants’ places of origin (all over Greece). The survey aimed to gather insights from highly educated individuals affiliated with universities, including students, graduates, and academic staff. Indeed, Table 2 presents the distribution of participants by gender, age, education level, occupational sector, and political orientation, along with corresponding percentages, offering a comprehensive overview of the sample’s characteristics. Table 2 indicates a mostly well-educated sample, with many participants either already holding or pursuing advanced degrees (bachelor, master, or PhD). These data show that the survey reached its intended audience. Over 65% of the sample holds at least a university degree, and nearly half (47%) hold a postgraduate degree (master’s or PhD), a much higher proportion than the general population in Greece, where postgraduate attainment is significantly lower. Specifically, according to OECD data in the report “Education at a Glance 2024,” Greece has the following percentages for the educational level of adults aged 25–64. In more detail, 8% hold a master’s degree, while 1% hold a doctoral degree. These percentages place Greece below the OECD average, where the percentage of adults with a master’s degree is approximately 14% and with a doctoral degree approximately 2% (OECD, 2024). All of the points indicate that this is a highly educated sample, possibly representing persons with greater access to or interest in research. It is also important to note that, though the characteristics of the sample limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader population this approach is well suited to the aims and needs of the present study.

Table 2.

Demographic and socio-political profile of survey participants.

Moreover, the occupational sector distribution shows a diverse mix of sectors, with education and the public sector being the most prominent, while others, such as media, legal services, and tourism, are also represented. This high representation from the education and public sectors (35.62%, and 14.32%, respectively) suggests that a significant portion of the participants in this category might hold an academic position in these three universities.

4. Analysis

Due to the variety of factors, including both binary, ordinal, and nominal scales, the analysis and extraction of results is based on several different statistical methods in order to derive meaningful conclusions from the data. The collected data were coded and normalized appropriately before conducting the statistical analyses, which were performed using the SPSS software Version 29. Subsequently, 33 participants were excluded from the analysis as they did not meet various eligibility criteria, such as a high level of education.

Descriptive statistics were applied to calculate the count and percentage of responses for each factor to summarize the distribution of answers (e.g., interest in news, preferred type of news, awareness of and concern about disinformation phenomenon, exposure to disinformation, medium, format and category of news with frequent disinformation, history of sharing disinformation, concern about ai contribution to disinformation etc.).

Chi-square tests were used to examine the associations between categorical variables (e.g., understanding the relationship between the frequency of visiting news websites—news engagement—and exposure to disinformation or history of sharing disinformation). Non-parametric tests, such as the Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis test, were used to compare ordinal data across different groups. These tests were applied to analyze variables such as concern about disinformation, comparing responses across categories defined by age, education level, gender, and political orientation.

Spearman’s rank correlation was applied to explore correlations between ordinal variables (e.g., analyzing the relationship between the frequency of visiting news websites with concern about the consequences of disinformation and the methods of verification usually used). Finally, cross-tabulations were used to explore relationships between binary and nominal data, such as analyzing the actions taken when realizing shared news was false and the methods of verification most used.

Through these various analyses, the extraction of meaningful insights was enabled, relevant to the research objectives such as behavior, awareness, and actions of this specific group regarding disinformation and media literacy. This valuable information will be instrumental in refining and customizing our MLC to better address the needs of this group.

5. Results

This section outlines the key findings derived from the survey data, structured according to the study’s three research questions. First, the level of concern among highly educated individuals in Greece regarding disinformation is examined, along with the key trends, characteristics, and behaviors that emerge from their responses concerning its perception, impact, and management (RQ1). Next, the analysis explores how participants respond to disinformation, focusing on the most and least frequently used fact-checking methods and their relationship with levels of news engagement (RQ2). Finally, the findings address the self-perceived psychological, social, and behavioral factors that influence participants’ decisions to share news content online, shedding light on the motivations and dynamics behind digital information sharing (RQ3).

5.1. News Engagement and Consumption Patterns

As expected, regarding “Interest in news,” most participants, 85.3%, indicated that they were interested, while 14.7% were not. Analyzing the factor aimed at capturing participants’ actual relationship with news content, “Frequency of visiting news websites,” the most common response was daily (56.9%), followed by the 22.3% who visit them 2–3 times a week, 12.9% “once a week” and 7.9% who visit news websites “once a month or never.” A noteworthy number of participants (7.9%) indicated that they browse news websites only once a month or not at all, which is relatively confusing considering the sample comprises persons engaged in academic pursuits.

Regarding “Interest in news during crises or significant events,” most participants expressed strong interest, with 88.9% indicating that they follow news closely during such times. In contrast, 11.1% of the participants indicated that they do not prioritize news during crises or significant events. The above distribution of the answers aligns with the general trend that major events often capture public attention.

Moving further into the issue of news engagement in relation to media literacy, the analysis focused on the actions participants take when they encounter a news item that captures their interest. Most participants stated that they “click on the post and visit the news source to read it” (72.1%). Additionally, 200 participants (23.7%) mentioned that they simply “read the post as it appears,” while 29 participants (3.4%) indicated that they “click on the post, visit the news source, read it, and share it.” A very small number of participants (0.8%), “read the post and share it without further exploration.” This finding suggests that most of the sample demonstrates a relatively active and critical engagement with news content.

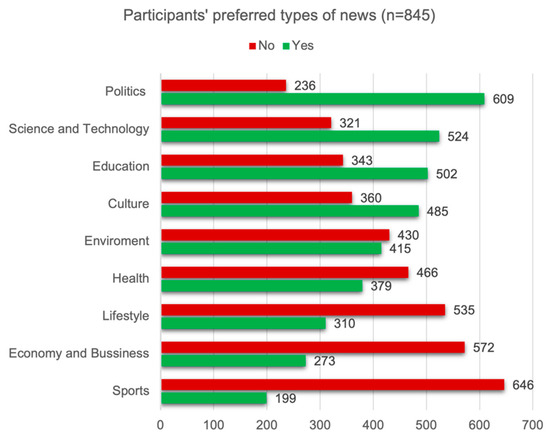

Τhe final element examined in this section is participants’ news preferences, aiming to shed light on the types of content they tend to follow or prioritize in their daily information consumption. The analysis of responses indicates distinct trends. “Politics” emerged as the most preferred category (72.0%). Similarly, “Science and Technology” was also highly favored (62.0%). Other popular news categories included “Education” (59.4%) and “Health” (44.9%). “Culture” and “Environment” also received notable attention, with 57.4% and 49.2% participants, respectively, expressing interest. In contrast, categories such as “Economy and Business” and “Sports” had slightly lower interest, with 32.3% and 23.6% respectively. Finally, “Lifestyle” was a moderately preferred category with 36.7% participants showing interest. Figure 1 illustrates the responses of the participants in each of the categories.

Figure 1.

Participants’ preferred types of news (thematic classification).

Based on the questions presented, the sample profile shows that most of the participants are very interested in news and browse news websites every day, although a small portion only go once a month or less. The majority pay close attention to the news during crises or major occurrences, and they actively read and click on news stories. Their main interests are politics and science and technology. Having outlined participants’ general news engagement and content preferences, the following section shifts focus to their awareness of and interaction with disinformation, examining their exposure, verification practices, and perceived capacity to respond to and combat misleading content.

5.2. Awareness, Exposure, and Responses to Disinformation

Awareness of the disinformation phenomenon was high, with 835 participants (98.8%) acknowledging its existence, while 10 (1.2%) did not. However, when asked about “concern for the consequences of disinformation,” 143 (16.9%) expressed low concern, 394 (46.6%) expressed high concern, and 308 (36.5%) expressed extreme concern. The above result reveals that, for most participants, disinformation is not merely a recognized phenomenon but also a significant social concern. This variation in levels of concern offers research value, as it allows for the further exploration of factors that may influence the intensity of worry, a topic that is discussed in more detail further below in the analysis.

Regarding “exposure to disinformation,” most of the participants 373 (44.1%) reported that they encountered false news often and 350 (41.5%) sometimes. It is noteworthy that a considerable portion of the participants reported rare exposure 122 (14.4%).

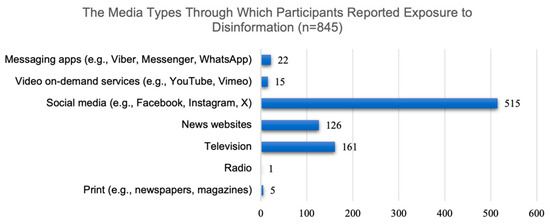

Concerning the medium through which participants encounter false information, social media was by far the most common platform, as 515 participants (60.9%) reported exposure to disinformation through these platforms. Television followed as the second most common medium, with 161 participants (19.0%) indicating exposure through this channel. News websites were also identified as a significant medium, with 126 participants (14.9%) reporting them as the primary channel of disinformation. Figure 2 presents the distribution of participants’ reported exposure to disinformation across different media channels.

Figure 2.

Media platforms through which participants reported exposure to disinformation.

Beyond the medium of exposure, the study also examined the format in which disinformation is typically encountered by participants. Specifically, text emerged as the most common form, with 499 participants (59.0%) reporting exposure to false information in text-based formats. Images were the second most common format, with 217 participants (25.7%) indicating that they encountered disinformation in this form. Videos accounted for 129 participants (15.3%), making it least common format for exposure to disinformation.

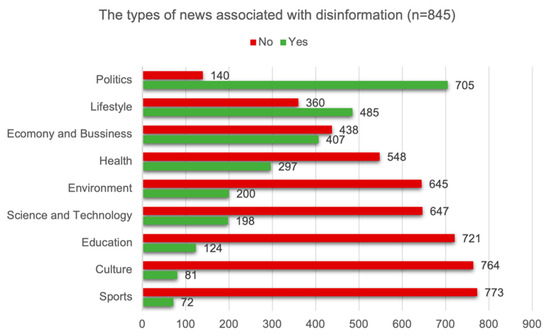

Participants were also asked about the kind of news they associate with disinformation, with the majority indicating that it typically appears in politics, lifestyle news and economy and business categories (Figure 3). This dual classification of politics (both as a news category that is likely to contain false information and one of the most popular news categories) is particularly interesting and may indicates that people, though they are aware of how often false or misleading information appears in “Politics,” are still very interested in following this category of news.

Figure 3.

The types of news participants associate with disinformation, with the most identified categories being politics and lifestyle.

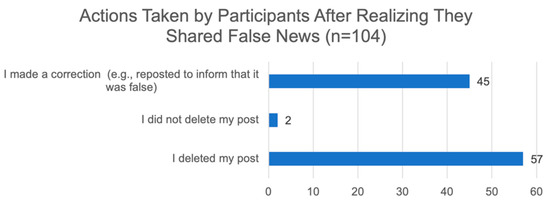

When asked to consider their past behavior regarding disinformation sharing, 104 (12.3%) participants admitted that they have shared disinformation, while a considerable portion 258 (30.5%) expressed uncertainty about this statement. Figure 4 presents the ways in which the 104 participants realized that they had shared disinformation, and Figure 5 illustrates the actions taken after realizing they shared false news.

Figure 4.

The various ways through which the 104 participants admitted to having shared disinformation in the past, having realizing its false nature.

Figure 5.

Actions taken by participants after realizing that the news they shared was false, including deletion, correction, or no action.

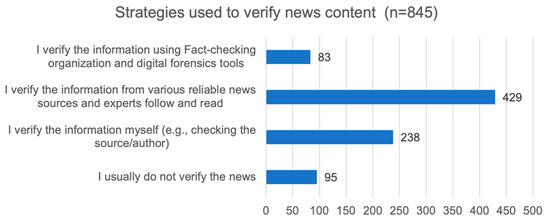

In terms of the strategies used to verify news content, Figure 6 presents the methods participants use. Most participants, 429 (50.8%), report that they verify the information by consulting various reliable news sources and the experts they follow and read. A total of 238 participants (28.2%) verify the information themselves by checking the source or author of the news. In contrast, 95 participants (11.2%) stated that they usually do not verify the news, while only 83 participants (9.8%) use fact-checking organizations and digital forensics tools to verify information.

Figure 6.

Participants’ news verification habits.

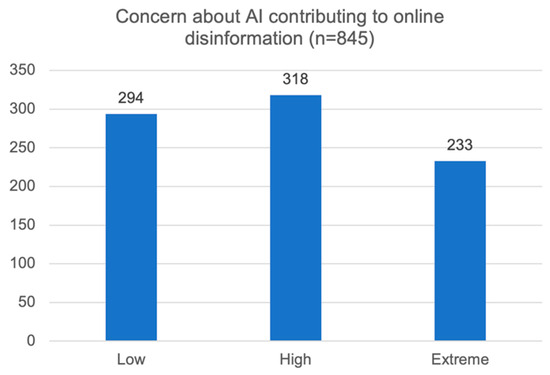

As AI-generated content becomes more common and tougher to identify, understanding participants’ concerns highlights potential risks and the growing need for improved digital literacy and regulatory measures. For this reason, the study investigated participants’ concern about the role of artificial intelligence in contributing to online disinformation, with a large number indicating high or extreme degrees of anxiety about its ability to propagate fake information (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Participants’ concern about AI contributing to online disinformation.

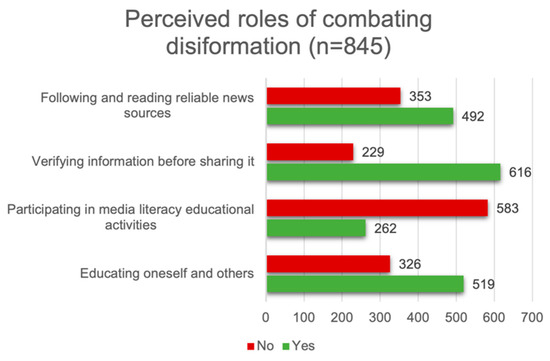

Another significant aspect of the study was understanding how individuals perceive their own role in combating disinformation, highlighting the types of actions they prioritize. Figure 8 depicts that “Verifying information before sharing it” and “Participating in media literacy educational activities” are perceived as a priority. While “Educating oneself and others” and “following reliable news sources” show moderate levels of importance.

Figure 8.

Contribution to combating online disinformation. Participants’ views on the most effective ways individuals can contribute to the fight against online disinformation.

Building upon the descriptive statistics, the next step involved conducting in-depth statistical analyses to better understand the relationships and patterns among the variables. The findings reveal significant relationships between various demographic variables (such as gender, age, education, and political orientation) and several attitudes, behaviors, and concerns related to disinformation. Table 3 includes the method used for analysis (e.g., Chi-square, Mann–Whitney, Kruskal–Wallis, Spearman coef.) and the p-value indicating the statistical significance of each relationship, providing a comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics at play.

Table 3.

Statistical tests (Chi-square and Mann–Whitney) and p-values for the relationship between gender and various factors related to disinformation, including interest in news, concern about disinformation, exposure to false news, and concerns about AI’s role in online disinformation.

A significant relationship was found between “Interest in news” and “Gender” (p = 0.003). A more detailed examination of the results reveals that women are more interested in the news. Another significant difference was found in the variable “Concern about disinformation,” which also indicates that gender correlates with the level of concern about the phenomenon of disinformation. Similarly, in this instance, women reported higher levels of anxiety. Additionally, gender is related with perceptions of “Frequency of exposure to false news” with women believing that they are exposed to fake news to a much greater extent than men. Finally, gender is also associated with the “Concern about AI contributing to online disinformation” with women reporting lighter levels of concern. However, there are no differences with regard to “Awareness of the phenomenon,” “Exposure to disinformation,” the “Medium through which they most often encounter disinformation” and the “Verification methods” used to check news authenticity.

Focusing on the age variable, a significant relationship was observed between “Interest in News” and “Age” (Table 4). Furthermore, concern about disinformation varies across different age groups (1–3, 1–4, 2–3, and 2–4). This indicates that concern about disinformation varies significantly by age, with certain groups exhibiting different levels of concern. Additionally, age plays a significant role in how individuals perceive disinformation. The distribution presented in Table 5 indicates that younger age groups (20 and 21–30) tend to express higher concern, with a significant portion reporting “High” and “Extremely High” levels of concern. In contrast, older age groups (31–50 and 51+) show more balanced or lower levels of concern about disinformation, particularly in the low concern category. These variations suggest that age influences the perceived threat of disinformation, with younger individuals demonstrating greater concern.

Table 4.

Statistical tests (Chi-square and Kruskal–Wallis) and p-values for the relationship between age and various factors related to disinformation, including interest in news, concern about disinformation, exposure to false news, and concerns about AI’s role in online disinformation.

Table 5.

Concern about disinformation among the age groups.

Finally, a significant relationship was found between the groups regarding the medium through which they are exposed to false news. The above finding indicates that different age groups are exposed to fake news through various channels.

Conversely, no significant relationship was detected between age groups and “Awareness of the disinformation phenomenon,” “Frequency of exposure to false news,” or the “Verification practices.” Hence, age does not notably correlate with the methods participants employ to verify information. Moreover, levels of concern regarding the role of AI in disinformation did not vary significantly by age.

The following variable tested was education. In this case, a significant relationship was found between “Interest in news” and “Education.” This indicates that individuals with different educational levels are more or less likely to report “Interest in news” (Table 6). Moreover, a notable difference was observed in “Concern about disinformation” among different academic levels. The findings indicate that individuals with lower academic backgrounds, such as university students, exhibit a greater concern regarding disinformation than those with advanced academic qualifications, like PhD holders. The pattern depicted in Table 7 suggests that advanced education might be linked to enhanced confidence in information processing or a deeper understanding of source evaluation, which could result in reduced anxiety regarding disinformation. Conversely, individuals with less educational attainment might experience heightened susceptibility to misinformation, leading to increased apprehension.

Table 6.

Statistical tests (Chi-Square and Kruskal–Wallis) and p-values for the relationship between education level and various factors related to disinformation, including interest in news, concern about disinformation, exposure to false news, and methods of verification.

Table 7.

Differences in concern about disinformation across education groups, highlighting significant variations between teams (1–2, 1–3, 1–4).

The results also show that education is associated not only with the types of channels but also with the format (text, photos, or video) through which they consume disinformation. Lastly, the study found a notable variation in the methods of verification usually used (p = 0.014), especially between groups 1 and 2. This notable variation between groups 1 and 2 can be explained by the fact that university students (Group 1) are more likely to use reliable sources and self-verification, even though a portion do not verify the news (40). The university graduates (Group 2) tend to rely slightly more on fact-checking organizations and reliable sources, but they engage less in self-verification compared with university students.

Education does not seem to substantially correlate with participants’ awareness of disinformation, their exposure to it, or their self-perception of being exposed to fake news.

Concerning political orientation, the analysis revealed several meaningful points. The first is associated with the “Interest in News” (Table 8). The level of “Interest in news” varies across different political orientation groups. The second involves the level of “Concern about disinformation,” which is framed by a negative correlation (−0.105). The distribution presented in Table 9 indicates that individuals with higher concern about disinformation tend to lean more toward the left or central political orientations. The “Right” group appears to have lower concern about disinformation overall, suggesting a potential political bias in the perception of disinformation. The third point suggests that political orientation may slightly differentiate how often individuals report encountering disinformation.

Table 8.

Statistical analysis results (Chi-square, Mann–Whitney, Kruskal–Wallis, Spearman) on the relationship between demographic variables and factors related to disinformation and media literacy.

Table 9.

The level of concern about disinformation between “Political Orientation” groups.

Correspondingly, no significant relationships were found between “Political Orientation” and awareness of the phenomenon, exposure to disinformation, the form of exposure to disinformation (e.g., text, image, video), verification methods and concern about the contribution of artificial intelligence to disinformation.

Moving beyond these initial observations, the analysis utilized the variable “Frequency of visits to news websites” to better understand the parameters that shape participants’ attitudes towards disinformation and the actions they take to guard themselves. This variable was chosen because it represents the actual interaction of participants with online news content, offering a realistic picture of their behavior. The analysis presented in Table 10 provides insights about the relationship between the “Frequency of visits to news websites” and various factors related to disinformation, such as concern about disinformation, exposure to disinformation, history of spread of disinformation, methods of verifying news, and concern about the contribution of AI to disinformation. The first observation is the negative correlation between the “Frequency of visits to news websites” and “Concern about disinformation” (Spearman coefficient is −0.202 with p < 0.001). This provides evidence that participants who visit news websites more often have slightly lower concern about the consequences of disinformation, with the correlation being negative. A further relationship was found between the “Sharing disinformation history” and the “Frequency of visits to news websites” (p = 0.025). Specifically, based on the presented data, daily visitors seem to report fewer instances of sharing disinformation (Table 11).

Table 10.

Statistical analyses exploring the relationships between the frequency of visiting news websites and various factors, including concern about disinformation, exposure to disinformation, history of sharing disinformation, methods of verification, and concern about AI’s role in online disinformation.

Table 11.

Distribution of participants’ history of sharing disinformation by frequency of news website visits.

Finally, another critical aspect is the correlation between the “Frequency of visits news websites” and the “Verification methods commonly used” (Spearman coefficient is −0.108 with p = 0.002). The negative relationship reveals that the more often the participants visit news websites, the less likely they are to use more extensive or careful verification methods (Table 12). It seems that participants who visit news websites daily tend not to verify news and use simple personal verification methods, while those who visit less frequently tend to use more verification strategies while also utilizing multiple sources or external fact-checking organizations and digital forensics tools. While the statistical significance of the results suggests that the observed relationships are unlikely to be due to random chance, it is important to note that the correlations identified are relatively weak. These weak correlations may not have substantial practical implications, and as such, should be interpreted as trends rather than strong, actionable relationships. No significant associations were observed for the other variables.

Table 12.

Distribution of participants’ methods of verification usually used ordered by frequency of news website visits.

Lastly, a dedicated set of items aiming to explore the broader psychological and social aspects of news sharing behavior offered further insights into participants’ “sharing content online” motivations. The most self-perceived motivations were receiving feedback and social interaction (53.6%) and the perception of influencing others (51.7%), suggesting that interpersonal and communicative needs are key drivers in participants’ decisions to share content. A smaller yet notable portion of respondents (28.1%) stated that they use sharing to save useful information. In contrast, only 9.6% indicated that sharing is a habitual practice, while even fewer participants shared for reasons of relaxation (4.5%) or the desire to be among the first to share information (4.5%) (Table 13).

Table 13.

The responses to various statements about sharing behavior, highlighting the percentages of participants who agree with each statement (n = 845).

Drawing insights from the presented results the discussion section interprets them in relation to the research questions. The section examines the implications of the data, specifically addressing how the outcomes correspond with or contest established theories and literature, followed by their analysis with an emphasis on their importance for MLC.

6. Discussion

The findings provide valuable insights into the behaviors, attitudes, and decision-making processes of highly educated individuals in relation to disinformation. Regarding the central hypothesis of the study, people with higher education levels are not resilient to disinformation, they are not always able to recognize their vulnerability to disinformation, and therefore, require advanced media literacy education to better identify, critically assess, and verify news, as well as consult reliable external sources.

In the above context the study’s results reveal that most participants (85.3%) are interested in news and pay close attention to news during crises of major events (88.9%). However, in terms of their frequency of visiting news websites, only 56.9% of them state that they do this “daily” and 7.9% visit news websites “once a month or never.” Hence, while participants report interest in news they do not actively access and consume it (RQ1).

The finding that a high percentage of participants is interested in news and pays close attention during major events or crises is consistent with several studies in the literature. Research often indicates that people are more likely to engage with news content during significant events (McCombs & Shaw, 1972). Furthermore, the frequency of visiting web sites reflects an interesting trend already discussed in the literature review about news consumption patterns. This decline in news consumption is often cited as being the result of “news fatigue,” “news avoidance,” and the overwhelming volume of information online (Lazer et al., 2018; Pulido et al., 2020; Villi et al., 2022). Moreover, many individuals no longer rely solely on traditional news websites and increasingly engage with news through social media platforms, apps, or news aggregators, per Nielsen and Graves (2017). The above could explain why 43.1% do not visit news websites daily but may engage with news with the aid of another channel.

In the opposite direction, awareness of the disinformation phenomenon was extremely high, with 835 participants (98.8%) reporting that they are aware of the situation. However, the concern about disinformation is lower, as 702 (83.1%) expressed high and extreme concern. Despite the slight decrease in the percentage, it remains overwhelming, suggesting that individuals understand the potential risks of disinformation in the digital landscape. This initial analysis shows that our sample does not exhibit signs of overconfidence (Beauvais, 2022) and that the participants do not believe they are immune to disinformation because they assume they have the skills to critically evaluate information.

However, additional evidence about the awareness of the phenomenon can be derived from the proportion of participants who answered that they encounter news often (44.1%), indicating the increasing prevalence and rapid spread of false information. Moreover, social media is the primary platform for encountering disinformation (60.9%) confirming the literature which repeatedly emphasizes that social media platforms are significant contributors to the rapid spread of disinformation (Nielsen & Graves, 2017; Vosoughi et al., 2018). However, it is worth noting that responsibility does not exclusively rely on the users, but the way the platforms operate also represents a dominant factor. For example, Pickard (2019), argues that media systems, especially those driven by commercial interests such as social media platforms, prioritize traffic and clicks in their sites. Through the pursuit of virality, the recipe for fake news, the distinction of false information is made difficult (Katsaounidou et al., 2018, 2020). Further insights into how social media platforms operate are provided by Pennycook and Rand (2019a), arguing that people have a strong desire to consume and share accurate information, but social media platforms often divert their attention away from the truth. Allen et al. (2020) further support this, showing that disinformation accounts for only a small percentage of the news people consume. However, it still appears more prevalent due to people’s constant exposure to it.

In addition to the findings on news engagement, disinformation awareness, and verification behaviors, significant relationships were observed between various factors and demographic variables, such as age and gender. These relationships provide deeper insights into how these factors influence concern about disinformation and individuals’ interaction with news content. A noteworthy relationship was found between age and concern about disinformation. Specifically, younger individuals expressed higher levels of concern compared with older participants. This suggests that younger people may be more aware of or sensitive to the risks associated with disinformation, possibly due to their greater digital media engagement and exposure to online content. Gender was another demographic factor that influenced responses. Women reported higher levels of concern about disinformation, as well as greater exposure to false or misleading news. These findings align with prior research suggesting that women may be more inclined to recognize and be cautious about disinformation, possibly due to heightened perceptions of risk or trust in online content (Bhati et al., 2022). These findings highlight the importance of considering demographic factors when developing MLC, as these factors correlate with individuals’ perceptions, concerns, and behaviors regarding disinformation.

The emergence of textual news, articles, and social media posts, which subjects perceived as the primary type of disinformation, is also a critical aspect. Text, being the easiest form of information to consume and share, forms a compelling medium for spreading disinformation. Moreover, Pennycook et al. (2021) emphasize that headlines often capture more attention than the full content, which could explain why misleading headlines, even when their accuracy is uncertain, continue to be widely shared.

Regarding their history in sharing disinformation, only 12.3% admitted doing so in the past, with 30.5% being uncertain, a reflection of unintentional sharing or a lack of awareness of the veracity of the information shared (Beauvais, 2022). Many people share disinformation unknowingly because they fail to critically evaluate its credibility, particularly when the content aligns with their pre-existing beliefs or emotional triggers (Pennycook & Rand, 2019b). In relation to the actions taken upon realizing they have shared false information, most participants reported deleting or correcting the post, possibly because of the feeling of social responsibility to correct the error, especially if the misinformation was shared within close-knit networks like friends and family (Tandoc, 2019).

As the analysis progresses, the focus shifts to how disinformation is responded to by highly educated individuals in Greece, particularly regarding concern about misinformation and the fact-checking methods employed (RQ2). According to the main areas of interest the analysis reveals several key relationships between the factors.

First, a negative correlation was found between the frequency of visits to news websites and concern about the consequences of disinformation, suggesting that more frequent visitors tend to express less concern. This relationship can be attributed to the absence of “news fatigue.” Daily news readers do not suffer from the phenomenon because they have the “appetite” and interest to consume news content for the constant updating of their knowledge about the daily agenda. Thus, believing they are equipped with the knowledge and experience that distance them from the possibility of being deceived by disinformation their awareness and precaution might be decreased. Indeed, individuals who visit news websites daily reported fewer instances of sharing disinformation. Our finding is in line with previous studies which found that overconfidence in one’s ability to discern accurate news can lead to a reduction in critical evaluation, which is likely reflected in the lower concern observed among frequent news consumers (Pennycook & Rand, 2019b).

Most notably, the frequency of news website visits was also negatively correlated with the use of extensive fact-checking methods, suggesting that those who visit news websites more frequently are less likely to employ rigorous verification strategies, instead relying on simpler personal methods. Conversely, less frequent visitors tend to use more thorough verification techniques, including multiple sources and external fact-checking tools. It seems that, despite the availability of multiple fact-checking options, participants tend to verify only what they consider to be a false claim on their own, being unaware of the current technological tools offered, and, most importantly, not utilizing the knowledge that professional fact-checkers produce (Graves & Cherubini, 2016). Similar findings are presented in the work of Corbu et al. (2020) regarding people’s self-perceived ability to detect fake news and of their perception of others’ ability to do the same.

To address RQ3, the study’s findings offer intriguing, yet preliminary, insights into the reasons shaping the behavior of highly educated individuals in Greece with regard to sharing news online. It is important to note that the self-reporting questionnaire used in this study captures participants’ stated reasons for sharing content but does not provide direct insights into the underlying mechanisms influencing such behavior. While the responses offer valuable perspectives on perceived motivations, they do not fully represent the actual factors driving participants’ actions, which highlights a key limitation in interpreting the findings.

When examining the 845 participants’ responses regarding their sharing behavior, several psychological factors come into focus. The first notable insight is the desire for influence—half of the respondents agreed that sharing makes them feel like they influence others. This suggests that, for many individuals, sharing news is a way of asserting their influence, shaping the opinions of others, and establishing a sense of control over the information landscape. Additionally, half of the participants also stated that sharing helps them interact and receive feedback, indicating that news sharing serves not just as a means of spreading information, but also as a form of social engagement. This aligns with the earlier findings that sharing is often driven by the potential for discussion and the desire for feedback. The social aspect of sharing is further emphasized by participants’ responses, with many stating that sharing helps them save useful information. This suggests that some individuals view sharing as a way to organize and preserve valuable content for future reference.

The insights highlight the perceived social and emotional factors influencing news sharing, where relevance, interaction, and feedback are seen as the most significant drivers by participants. While emotional responses are also present, they are generally perceived as secondary to these social and rational motivations. Given these patterns, it is evident that MLC that seeks to battle disinformation should focus on helping individuals also to recognize the social dynamics that influence their sharing behavior, fostering more critical thinking around the accuracy of the news they encounter and share.

Enhancing Media Literacy Education for Highly Educated Individuals: Insights from Our Data

The data collected and analyzed in the present study offers essential insights that can guide the development of (MLC) specifically tailored for highly educated individuals in Greece. These findings collectively underscore the need for advanced MLE strategies that address both the behavioral patterns and psychological factors that shape individuals’ relationship with information in the digital age.

One of the key insights from the study is the discrepancy between the participants’ expressed interest in news and their actual news consumption habits. This gap between interest and consumption highlights the need for MLE programs that encourage more consistent and engaged news consumption. Specifically, MLC should focus on combating the factors contributing to “news avoidance” and “fatigue,” which are prevalent among individuals even with high education levels. By incorporating strategies that make news consumption more engaging, efficient, and less overwhelming, MLE can help individuals develop a more habitual approach to accessing news from reliable sources.

Additionally, the study found that, while participants were generally highly aware of disinformation, their concern about the consequences of disinformation was lower, with few expressing high or extreme concern. The results suggest that highly educated individuals are not immune to disinformation but might instead underestimate their vulnerability to it. This finding emphasizes that MLE must focus on fostering a deeper understanding of the cognitive biases and social dynamics that contribute to susceptibility, even among well-educated individuals. By addressing these biases, MLE can encourage more critical self-reflection and increase awareness of the subtle ways in which disinformation spreads, particularly on social media platforms.

Moreover, the analysis also reveals that social media platforms were identified as the primary channel for encountering disinformation. MLC should focus not only on identifying disinformation but also on understanding the mechanics behind its spread, such as algorithms that prioritize sensational or emotionally engaging content. In addition, initiatives should promote skills that help individuals navigate these platforms more effectively, recognizing that they must not only critically assess the content itself but also understand the broader context in which it is disseminated.

The findings regarding participants’ behavior when sharing disinformation also offer key insights for MLC design. The overall uncertainty reflects the difficulty in accurately assessing the truthfulness of content, particularly when it aligns with personal beliefs or emotional triggers. MLC should focus on teaching individuals to recognize the cues that make content more likely to be misleading. Furthermore, the fact that most participants reported deleting or correcting false information once they recognized their mistake indicates a strong sense of social responsibility. MLC can build on this sense of accountability by encouraging responsible sharing practices and providing tools that help individuals quickly verify information before sharing it.

The data revealed that a significant portion of participants expressed high concern about AI’s role in spreading disinformation, highlighting the need for MLC to focus on the challenges posed by AI-generated content. As AI tools rapidly evolve, MLE must address how these technologies can amplify misleading information. Additionally, when asked how individuals can combat disinformation, most participants emphasized the importance of “educating themselves and others” and “verifying information before sharing.” This underscores the need for MLC to not only teach critical thinking skills but also promote a culture of responsibility in sharing accurate information.

The analysis also showed that participants were more inclined to share news based on its perceived importance (88.1%) and its potential to drive social interaction (83.1%). These motivations emphasize the social aspect of news sharing, driven more by the desire to engage in discussions or express personal opinions than by the intent to inform others or spread disinformation. MLC should, therefore, address the social and emotional drivers of news sharing. It should not only teach individuals how to critically assess news content but also help them recognize the underlying motivations for sharing news, such as the desire for social validation or to feel “in the know.” Understanding these motivations will help individuals make more informed decisions about whether to share information, especially when they are uncertain of its accuracy.

Finally, the study’s findings regarding participants’ use of fact-checking methods revealed a significant gap in their verification practices. Despite the availability of numerous fact-checking resources, frequent visitors to news websites were less likely to use extensive verification methods and instead relied on personal judgment. This suggests that even highly educated individuals may overestimate their ability to discern the truth of news stories, relying on less rigorous methods for evaluation. MLC should, therefore, place a strong emphasis on teaching participants about the importance of using multiple sources and external fact-checking tools to verify information. Encouraging the use of professional fact-checking organizations and digital forensics tools could improve the accuracy of the information individuals consume and share.

In conclusion, the findings from this study offer several key directions for enhancing MLE for highly educated individuals in Greece. The insights gained from participants’ behaviors, motivations, and attitudes toward news consumption, disinformation, and sharing practices provide a foundation for developing more targeted and effective MLC.

7. Limitations and Future Work

It must be acknowledged that the present study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results, and these limitations point to areas for future work to improve our understanding of disinformation and how it affects highly educated individuals.

Firstly, the study focused primarily on a specific group of participants in Greece, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations. Future research should include more diverse samples, considering factors such as cultural context, geographic location, and different educational backgrounds. By expanding the demographic scope, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of how education level, region, and culture influence susceptibility to disinformation.

Additionally, while the study provided useful insights into the frequency of news consumption and its relationship with concern about disinformation, it did not explore the full range of news consumption habits, including the role of social media platforms, apps, and news aggregators. Future work should investigate the role these alternative sources play in shaping people’s perceptions of disinformation, especially as social media continues to dominate news consumption. The study also found that participants showed varying levels of concern about disinformation, with some indicating high concern but still engaging in behaviors that suggested limited critical engagement with news content. This inconsistency suggests that future work should delve deeper into the factors that mediate news consumption and verification behaviors. Investigating these factors could lead to more targeted MLE interventions that address not just knowledge gaps but also underlying motivations and biases. Lastly, while the study explored the relationship between news consumption frequency and the use of fact-checking methods, the reasons behind this relationship were not fully investigated. Future work should focus on understanding why people rely on simpler verification methods instead of utilizing the state of the art in the verification industry.

In conclusion, while the study provides valuable insights into how highly educated individuals respond to disinformation, addressing these limitations through future work can help create a more complete picture and contribute to the development of optimized MLC and more targeted and impactful strategies to combat disinformation in today’s digital landscape.

8. Conclusions

Overall, the present study contributes to the scientific debate on disinformation by portraying the complex ways in which news consumption, social influences, and psychological factors interact to shape people’s perceptions and sharing of disinformation. The findings indicate that addressing disinformation requires more than improving media literacy or promoting fact-checking. Contrary to expectations, highly educated individuals did not exhibit the anticipated level of sophisticated verification skills, as reflected in their self-reported questionnaire responses. Frequent news consumption was not necessarily associated with a greater understanding of disinformation; in some cases, it even led to a reduced concern about the phenomenon.

It was also expected that participants would have greater trust in fact-checking organizations and use them regularly. However, the research revealed that, although participants were aware of the existence of fact-checking organizations, their resources were rarely used. In this context, further research is necessary to point out how these organizations would strengthen their presence, appeal, and engaging character.

Overall, this is another study supporting the idea that everyone is vulnerable to online disinformation, even at the higher levels of education and knowledge (which is the main question here). This is further deteriorated by the fact that, currently, at a time when developments in artificial intelligence are advancing rapidly, our knowledge and technical skills often become obsolete ever more quickly.

In this context, our instincts for distinguishing truth from falsehood are profoundly altered, as is our belief in having full control. While we may possess the skills to navigate the challenges of the digital world, this confidence often causes us to overestimate our abilities and underestimate the seriousness of disinformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K., T.S., E.S., E.K., C.D. and A.V.; Methodology, A.K., T.S., E.S. and E.K.; Data curation, A.K.; Writing—original draft, A.K. and C.D.; Writing—review & editing, T.S., E.S. and E.K.; Visualization, A.K. and C.D.; Supervision, A.V.; Project administration, A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the MedDMO hub/Digital Europe Programme, Grant Number 101083756.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was conducted in accordance with the procedures and regulations set forth by the Committee on Research Ethics and Conduct of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (ref. number 44738/2023) and participation was anonymous. Prior to submitting their responses, respondents were required to indicate their acceptance of the stated terms.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to ethical restrictions and in accordance with the approval granted by the Ethics Committee of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH), the datasets generated and analyzed during the current study cannot be made available. The data are fully anonymous and are used solely for research purposes within the framework of the project, as specified in the approved ethical protocol. Public sharing or transfer of the data to any third party is not permitted; only aggregated and statistical results may be made available or reported. The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Notes

| 1 | Snopes.com available at https://www.snopes.com/ (accessed on 10 July 2025). |

| 2 | Politifact.com available at https://www.politifact.com/ (accessed on 14 July 2025). |

| 3 | Ellinika hoaxes available at https://www.ellinikahoaxes.gr/ (accessed on 14 July 2025). |

| 4 | Fact Review available at https://factreview.gr/ (accessed on 12 July 2025). |

| 5 | Greece fact check available at https://www.factchecker.gr/ (accessed on 1 August 2025). |

| 6 | AFP Greece fact check available at https://factcheckgreek.afp.com/ (accessed on 23 July 2025). |

| 7 | Image Verification Assistant available at https://mever.iti.gr/forensics/ (accessed on 26 July 2025). |

| 8 | MAAM available at https://maam.mever.gr/about (accessed on 26 July 2025). |

| 9 | InVID verification plugin available at https://www.invid-project.eu/ (accessed on 18 June 2025). |

| 10 | The Digital Services Act: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-services-act-package (accessed on 3 August 2025). |

| 11 | More information available at https://edmo.eu/about-us/edmo-hubs/ (accessed on 7 August 2025). |

References

- Allen, J., Howland, B., Mobius, M., Rothschild, D., & Watts, D. J. (2020). Evaluating the fake news problem at the scale of the information ecosystem. Science Advances, 6(14), eaay3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amazeen, M. A. (2020). Journalistic interventions: The structural factors affecting the global emergence of fact-checking. Journalism, 21(1), 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, V., & McStay, A. (2018). Fake news and the economy of emotions: Problems, causes, solutions. Digital Journalism, 6(2), 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, J. P., & Gradim, A. (2022). Who believes in fake news? Identification of political (a) symmetries. Social Sciences, 11(10), 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, Z., Barua, S., Aktar, S., Kabir, N., & Li, M. (2020). Effects of misinformation on COVID-19 individual responses and recommendations for resilience of disastrous consequences of misinformation. Progress in Disaster Science, 8, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashardoust, A., Feuerriegel, S., & Shrestha, Y. R. (2024). Comparing the willingness to share for human-generated vs. AI-generated fake news. arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauvais, C. (2022). Fake news: Why do we believe it? Joint Bone Spine, 89(4), 105371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, N., Pal, Y., & Talwar, T. (2022). Social media fatigue and academic performance: Gender differences. In V. Mahajan, A. Chowdhury, U. Kaushal, N. Jariwala, & S. A. Bong (Eds.), Gender equity: Challenges and opportunities (pp. 331–337). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, A. (2005). Gatewatching: Collaborative online news production (Vol. 26). Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, M., Lee, F. L., & Chen, H. T. (2022). Avoid or authenticate? A multilevel cross-country analysis of the roles of fake news concern and news fatigue on news avoidance and authentication. Digital Journalism, 12(3), 356–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbu, N., Oprea, D.-A., Negrea-Busuioc, E., & Radu, L. (2020). ‘They can’t fool me, but they can fool the others!’ Third person effect and fake news detection. European Journal of Communication, 35(2), 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K. M., Uscinski, J. E., Sutton, R. M., Cichocka, A., Nefes, T., Ang, C. S., & Deravi, F. (2019). Understanding conspiracy theories. Political Psychology, 40, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, U. K., Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Schmid, P., Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N., Kendeou, P., Vraga, E. K., & Amazeen, M. A. (2022). The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(1), 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, N. (2022). No news is not good news: The implications of news fatigue and news avoidance in a pandemic world. Athens Journal of Mass Media and Communications, 8(3), 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giomelakis, D., Constandinides, C., Noti, M., & Maniou, T. A. (2024). Investigating online mis-and disinformation in Cyprus: Trends and challenges. Journalism and Media, 5(4), 1590–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L., & Cherubini, F. (2016). The rise of fact-checking sites in Europe (Reuters institute digital news report). Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, E. A., DeMora, S. L., & Albarracín, D. (2024). The consequences of misinformation concern on media consumption. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 5(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermida, A. (2010). Twittering the news: The emergence of ambient journalism. Journalism Practice, 4(3), 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. S., Ferdous, M. Z., & Potenza, M. N. (2020). Panic and generalized anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic among Bangladeshi people: An online pilot survey early in the outbreak. Journal of Affective Disorders, 276, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaounidou, A. N., Dimoulas, C., & Veglis, A. (Eds.). (2018). Cross-media authentication and verification: Emerging research and opportunities: Emerging research and opportunities. IGI-Global. [Google Scholar]

- Katsaounidou, A. N., Gardikiotis, A., Tsipas, N., & Dimoulas, C. A. (2020). News authentication and tampered images: Evaluating the photo-truth impact through image verification algorithms. Heliyon, 6(12), e05808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, D. M., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S. A., Sunstein, C. R., Thorson, E. A., Watts, D. J., & Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S. (2004). What is media literacy? Intermedia, 32(3), 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., & Stoilova, M. (2023). The outcomes of gaining digital skills for young people’s lives and wellbeing: A systematic evidence review. New Media & Society, 25(5), 1176–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Majerczak, P., & Strzelecki, A. (2022). Trust, media credibility, social ties, and the intention to share towards information verification in an age of fake news. Behavioral Sciences, 12(2), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchal, N., Xu, R., Elasmar, R., Gabriel, I., Goldberg, B., & Isaac, W. (2024). Generative AI misuse: A taxonomy of tactics and insights from real-world data. arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]