From Victim to Avenger: Trump’s Performance of Strategic Victimhood and the Waging of Global Trade War

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Communication of Authoritarian Populism: Style, Strategies, and Discursive Disruption

3. Victimhood as a Communicative Politics of Authoritarian Populists

“…a person is “victimized” when he or she is nominated for membership in the “victim” category. Calling someone a victim organizes understandings of that person as a particular type to whom certain characteristics are attributed and orientations are taken” (Holstein & Miller, 1990, p. 106; italics in the original).

Drawing upon Illouz’s (2007) description of 20th-century modernity as “emotional capitalism”, Chouliaraki capitalizes on the novel configuration of emotion, economy, and technology that has rendered victimhood hegemonic in Western politics and culture, as well as the significance of victimhood in the context of contemporary discursive struggles and culture wars. The politics of pain is part of emotional capitalism and is interwoven with the interests of the powerful, while the pain of the vulnerable (on grounds of class, race, and gender) is muted and rendered invisible in public perception. At the same time, competing claims to pain can enter the marketplace without being justified or proven true, as dominance in the marketplace is achieved by those who have access to the most resources:“victimhood is not a stable identity but a contingent and malleable speech-act, a linguistic claim to suffering that bears no necessary relationship to the structural vulnerabilities the claimant may be experiencing” (Chouliaraki, 2024a, p. 103).

Victimhood is often tied to the construction of national identity and can be used as justification for policy goals, portrayed as necessary for restoring national dignity. Research on victimhood nationalism in international politics (Lerner, 2020; Xu & Zhao, 2023) shows how victimhood narratives build on perceived or real collective trauma to project grievances against constructed victimizers (other groups or nations) and legitimize aggressive foreign policy. Moreover, by constructing national identity rooted in shared suffering, right-wing populists often emphasize historical victimhood as a moral framework to justify vindictive policies and mobilize voters against minorities (Meijen & Vermeersch, 2024).Who is produced as a victim, around which claim to suffering, and within which community of belonging are thus questions of political communication that cannot be taken for granted but are precisely the stake in the critical analysis of public discourse” (Chouliaraki, 2024a, p. 29).

4. Data and Methodology

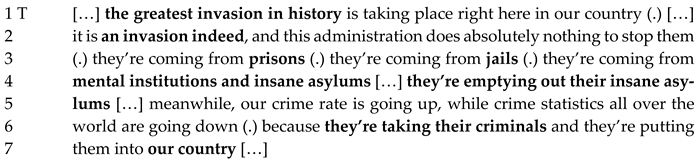

5. Victimhood as a Versatile Strategy in Trump’s Authoritarian Populist Discourse

- Construct various ‘victims’ and ‘victimizers’,

- Achieve optimized self-presentation while concurrently dispelling accusations and criticism,

- Vilify and demonize political opponents and social outgroups (illegal immigrants) and, ultimately, to accrue political leverage.

5.1. The Lexical Encoding of Enduring Victimhood

The same claim to victimhood underlies Trump’s use of “election interference”. In a Fox News interview to Sean Hannity in March 2023, Trump’s labels the legal accusations he was facing at the time as an orchestrated attempt by his opponents to intercept his bid for the presidency in the 2024 US elections:[…] If democrats want to unify our country, they should drop these partisan witch hunts, which I’ve been going through for approximately eight years […]

Almost four years into his first-term presidency of the USA, and despite him being a member of the US financial elite and a media celebrity, Trump has persistently portrayed himself as an outsider to the political system and a fighter for ‘the people’, who is persecuted by Washington elites, as in the following Instagram post from 18 September 2020:[…] it’s a - new way of cheating on elections (.) it’s called election - interference (.) what they’re doing, […]

[…] but what they do is misinformation and disinformation, and they keep saying (.) (mocking tone of voice) he’s a threat to democracy and I’m saying what the hell did I do for democracy:: (1.0) last week I took a bullet for democracy

Through constructed dialogue (Ekström & Patrona, 2024; Montgomery, 2020) that playfully mocks his opponents, he thus represents himself as a martyr for democracy rather than the potential tyrant-to-be that his enemies paint him as, a claim which triggers, as the extract illustrates, an enthusiastic response from his followers.(crowd cheers)

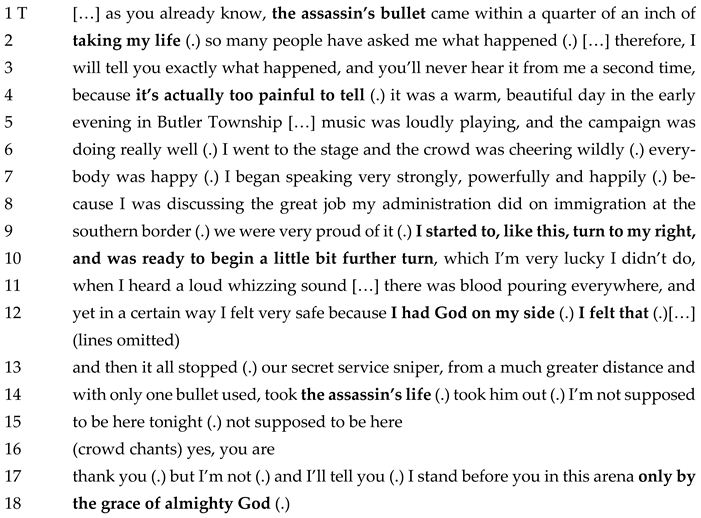

5.2. Constructing ‘Victims’ and ‘Victimizers’ Through Narrative Discourse

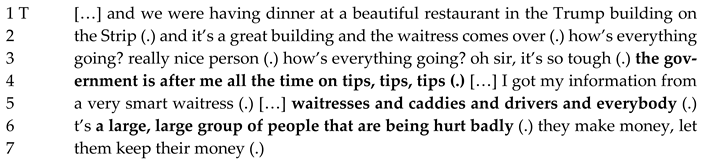

5.3. ‘The People’ as Victimized

6. Claiming Inflicted Pain to Announce Economic Retribution: An Empowered Post-Election Politics of Cynicism and Coercion

- ▪

- ‘The United States has been ripped o:ff, (1.0) by virtually every country in the world’.

- ▪

- ‘We’ve helped everybody we’ve been helping everybody for years’.

- ▪

- ‘To be honest, I don’t think they appreciate it’.

- ▪

- ‘So we’re gonna change that we’re gonna change it fast’.

- ▪

- ‘We put tariffs on […] and I’m sure they’re gonna pa:y’.

- ▪

- ‘We’re gonna make America great agai:n’.

[…] our sovereignty, (.) will be reclaimed, (1.0) our safety will be restored, (1.0) the scales of justice, will be: rebalanced, (.) the vicious, violent and unfair weaponization of the: justice department and our government (.) will end –

(audience applause)

- ▪

- “Our safety will be restored”

- ▪

- “The American dream will soon be back and thriving like never before”

- ▪

- “Bring back free speech to America”

- ▪

- “And we are going to bring law and order back to our cities”

- ▪

- “In recent years our nation has suffered greatly (.) but we are going to bring it back and make it great again”

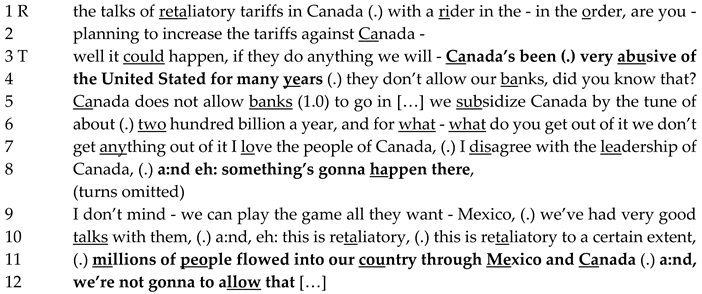

Leveraging Pain to Perform Global Trade War

7. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| (1.0) | Silence/pause in seconds |

| (.) | micropause of less than one second |

| >word< | Talk between the symbols is compressed or rushed |

| wo::rd | Stretching of the sound preceding the colons |

| word? | Rise in intonation indicating a question |

| word- | A hyphen after a word or part of a word indicates self-interruption |

| word | Underlining indicates emphasis on the underlined word or part of a word |

| (text) | Text in parentheses marks the transcriber’s description of the interaction |

| 1 | The terms ‘authoritarian populism/-ist’ and ‘far-right populism/-st’ are used interchangeably in the article, as they reference the same political actors, although different terms highlight different characteristics of these actors (see Ekström & Patrona, 2024, p. 3). |

| 2 | For the transcription conventions used for oral talk and conversation, see Appendix A. |

References

- Al-Ghazzi, O. (2021). We will be great again: Historical victimhood in populist discourse. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 24(1), 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, B., & Manning, J. (2018). The rise of victimhood culture: Microaggressions, safe spaces, and the new culture wars. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouliaraki, L. (2021). Victimhood: The affective politics of vulnerability. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 24(1), 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouliaraki, L. (2024a). Wronged: The weaponization of victimhood. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chouliaraki, L. (2024b, September 4). The weaponization of victimhood. Available online: https://www.postneoliberalism.org/articles/the-weaponization-of-victimhood/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Chouliaraki, L., & Banet-Weiser, S. (2021). Introduction to special issue: The logic of victimhood. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 24(1), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- cnn.com. (2025). ‘Fact check: Trump’s false claims about tariffs and trade’. Dale, D. 2 April 2025. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2025/04/02/politics/fact-check-trump-tariffs-trade/index.html (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Cole, A. (2007). The cult of true victimhood: From the war on welfare to the war on terror. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coston, B. M., & Kimmel, M. (2012). White men as the new victims: Reverse discrimination cases and the Men’s Rights Movement. Nevada Law Journal, 13, 368. [Google Scholar]

- Ekström, M., & Patrona, M. (2024). Authoritarian populism and the challenges for news journalism: A discourse approach. London; Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ekström, M., Patrona, M., & Thornborrow, J. (2018). Right-wing populism and the dynamics of style: A discourse-analytic perspective on mediated political performances. Palgrave Communications, 4(83). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, M., Patrona, M., & Thornborrow, J. (2020). The normalisation of the populist radical right in news interviews: A study of journalistic reporting on the Swedish Democrats. Social Semiotics, 30(4), 466–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, M., Patrona, M., & Thornborrow, J. (2022). Reporting the unsayable: Scandalous talk by right-wing populist politicians and the challenge for journalism’. Journalism, 23, 955–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- factcheck.org. (2025). ‘Trump’s misleading tariff chart’. Farley, R. and Gore, D. 3 April 2025. factcheck.org: A project of the annenberg public policy center. Available online: https://www.factcheck.org/2025/04/trumps-misleading-tariff-chart/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Feldman, O. (Ed.). (2023). Debasing political rhetoric: Dissing opponents, journalists, and minorities in populist leadership communication. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gardell, M. (2021). Lone wolf race warriors and white genocide. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gounari, P. (2018). Authoritarianism, discourse and social media: Trump as the ‘American Agitator’. In J. Morelock (Ed.), Critical theory and authoritarian populism (pp. 207–227). University of Westminster Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, K., & Kubin, E. (2024). Victimhood: The most powerful force in morality and politics. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 137–220. [Google Scholar]

- Hameleers, M. (2023). Debasing language expressed by two radical right-wing populist leaders in The Netherlands: Geert wilders and thierry baudet. In O. Feldman (Ed.), Debasing political rhetoric. The language of politics. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson, S. (2024). Coercive impoliteness and blame avoidance in government communication. Discourse, Context & Media, 58, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, J. A., & Miller, G. (1990). Rethinking victimization: An interactional approach to victimology. Symbolic Interaction, 13(1), 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hronešová, J. B., & Kreiss, D. (2024). Strategically hijacking victimhood: A political communication strategy in the discourse of Viktor Orbán and Donald Trump. Perspectives on Politics, 22(3), 717–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humprecht, E., Amsler, M., Esser, F., & Van Aelst, P. (2024). Emotionalized social media environments: How alternative news media and populist actors drive angry reactions. Political Communication, 41(4), 559–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illouz, E. (2007). Cold intimacies: The making of emotional capitalism. Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, M.-L. (2024). Populist blame games. In M. Flinders, G. Dimova, M. Hinterleitner, R. A. W. Rhodes, & R. K. Weaver (Eds.), The politics and governance of blame. Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killian, L. M. (1985). The stigma of race: Who bears the mark of Cain? Symbolic Interaction, 8(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyżanowski, M. (2020). Discursive shifts and the normalisation of racism: Imaginaries of immigration, moral panics and the discourse of contemporary right-wing populism. Social Semiotics, 30(4), 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyżanowski, M., Ekman, M., Nilsson, P. E., Gardell, M., & Christensen, C. (2021). Un-civility, racism and populism: Discourses and interactive practices of anti- & post-democratic communication. Nordicom Review, 42, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyżanowski, M., & Ekström, M. (2022). The normalization of far-right populism and nativist authoritarianism: Discursive practices in media, journalism and the wider public sphere/s. Discourse & Society, 33(6), 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyżanowski, M., & Ledin, P. (2017). Uncivility on the web: Populism in/and the borderlinediscourses of exclusion. Journal of Language and Politics, 16(4), 566–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyżanowski, M., Wodak, R., Bradby, H., Gardell, M., Kallis, A., Krzyżanowska, N., Mudde, C., & Rydgren, J. (2023). Discourses and practices of the ‘New Normal’. Journal of Language and Politics, 22(4), 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, W. (1972). The transformation of experience in narrative syntax. In W. Labov (Ed.), Language in the inner city: Studies in the Black English vernacular (pp. 354–396). University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leezenberg, M. (2015). Discursive violence and responsibility: Notes on the pragmatics of Dutch populism. Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict, 3(1), 200–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lerner, A. B. (2020). The uses and abuses of victimhood nationalism in international politics. European Journal of International Relations, 26(1), 62–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Dus, N., & Nouri, L. (2021). The discourse of the US alt-right online—A case study of the traditionalist worker party blog. Critical Discourse Studies, 18(4), 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- lse.ac.uk. (2025). ‘The weaponisation of victimhood’. 28 January 2025. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/research/research-for-the-world/society/weaponisation-victimhood (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- McNeill, A., Pehrson, S., & Stevenson, C. (2017). The rhetorical complexity of competitive and common victimhood in conversational discourse. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijen, J., & Vermeersch, P. (2024). Populist memory politics and the performance of victimhood: Analysing the political exploitation of historical injustice in Central Europe. Government and Opposition, 59(3), 932–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M. (2020). Populism in performance? Trump on the stump and his audience. Journal of Language and Politics, 19(5), 733–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikander, P. (2008). Constructionism and discourse analysis. In J. A. Holstein, & J. F. Gubrium (Eds.), Handbook of constructionist research (pp. 413–428). The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- reuters.com. (2025). ‘Trump’s tariff formula confounds the world, punishes the poor’. John, M. 4 April 2024. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/trumps-tariff-formula-confounds-world-punishes-poor-2025-04-03/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sengul, K. (2021). ‘It’s OK to be white’: The discursive construction of victimhood, ‘anti-white racism’ and calculated ambivalence in Australia. Critical Discourse Studies, 19(6), 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömbäck, J., & Esser, F. (2014). Introduction: Special issue on mediatization of politics: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. Journalism Practice, 8(3), 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J. H., & Stets, J. E. (2006). Moral Emotions. In J. E. Stets, & J. H. Turner (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of emotions. Handbooks of sociology and social research. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, T. A. (2025). Discourse and ideologies and of the radical right. (Series: Elements in Critical Discourse Studies). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, R. (2021). The politics of fear: The shameless normalisation of far-right discourse (2nd Revized ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, R. (2024). Appeals to “Normality” and “Common Sense” in the face of global uncertainty: An interdisciplinary discourse-historical approach. Informal Logic, 44(3), 361–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodak, R., Culpeper, J., & Semino, E. (2021). Shameless normalisation of impoliteness: Berlusconi’s and Trump’s press conferences. Discourse and Society, 32(3), 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., & Zhao, J. (2023). The power of history: How a victimization narrative shapes national identity and public opinion in China. Research & Politics, 10(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I. F., & Sullivan, D. (2016). Competitive victimhood: A review of the theoretical and empirical literature. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patrona, M. From Victim to Avenger: Trump’s Performance of Strategic Victimhood and the Waging of Global Trade War. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030134

Patrona M. From Victim to Avenger: Trump’s Performance of Strategic Victimhood and the Waging of Global Trade War. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(3):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030134

Chicago/Turabian StylePatrona, Marianna. 2025. "From Victim to Avenger: Trump’s Performance of Strategic Victimhood and the Waging of Global Trade War" Journalism and Media 6, no. 3: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030134

APA StylePatrona, M. (2025). From Victim to Avenger: Trump’s Performance of Strategic Victimhood and the Waging of Global Trade War. Journalism and Media, 6(3), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030134