Abstract

This literature review examines the psychological safety of journalists reporting on war, conflict, and terrorism, synthesizing contemporary research on trauma exposure, mental health outcomes, and institutional support. Using a systematic search strategy, 88 peer-reviewed studies from 2000 to 2024 were thematically analyzed. Key findings reveal elevated rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety among conflict journalists, comparable to the trauma experienced by combat veterans. Recommendations for advancing theory and research to create effective interventions to safeguard journalists’ well-being worldwide are discussed.

1. Introduction

Journalists reporting on war, terrorism, and conflict face unparalleled risks to their psychological and physical well-being. They face the risk of direct violence, witness human suffering, and are often recipients of untold narratives and horrible images, leading to conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and substance abuse (Obermaier et al., 2023). Such events and incidents directly impact their mental capacity and influence their perception of reality. In these situations, Fatima et al. (2023) stressed that the relationship between trauma exposure and mental health symptoms such as stress, anxiety, and depression experienced by journalists is moderated by their primary appraisals of traumatic events, such as the harm, loss, threats, or challenges they faced. This assertion was found by Radoli’s (2024) research, which found a positive correlation between journalists’ exposure to violent images and the development of trauma symptoms. However, Siddiqua and Iqbal (2024) and Pearson et al. (2019) found that most journalists fail to comprehend the importance of reporting traumatic events due to their excitement about war reporting. Seely (2019) extended the consequences attributed to this failure of reporting trauma by documenting how the frequency and intensity of trauma coverage correlate with increased PTSD symptoms. All of this corroborates the reality that reporting on traumatic events such as conflict and war can negatively affect journalists’ mental health (Markovikj & Serafimovska, 2023). Moreover, these effects were not uniform. For example, Levaot (2013) conducted a comparative study between Israeli journalists and their colleagues from Western countries and revealed that both Israeli and Western journalists reported high exposure to traumatic events in their work. However, Western journalists showed more PTSD symptoms and alcohol consumption, whereas Israeli journalists exhibited higher levels of depression, anxiety, and somatic distress than their Western counterparts. Despite these risks, mental health support for journalists covering traumatic events often remains an afterthought (Jukes, 2015). Compounding the problem, as Chadli et al. (2022) note, is the fact that, despite facing psychological and physical problems, journalists do not abandon their jobs or request special privileges. To highlight the severity of this problem, Feinstein et al. (2002) argued that the prevalence of PTSD among war journalists is comparable to that of combat veterans, with a sizable portion also experiencing major depression. Despite their critical role in disseminating information, the mental health challenges and occupational hazards encountered by journalists remain understudied. This study synthesizes existing research on trauma exposure, psychopathology, and safety mechanisms in conflict journalism, while proposing future directions for interdisciplinary inquiry and institutional reform.

2. Theoretical Framework

This review applies three interrelated theoretical frameworks that elucidate the intricate dynamics of mental health among journalists engaged in reporting on warfare and conflict: Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, Organizational Support Theory (OST), and the Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) model.

The Conservation of Resources Theory, as posited by Hobfoll (1989), offers a conceptual foundation for understanding how journalists encounter and react to psychological stressors in conflict zones. According to COR theory, individuals endeavor to acquire, preserve, and safeguard the resources they deem valuable, and psychological stress arises when these resources are jeopardized or diminished. Within the realm of war journalism, these resources include physical safety, professional autonomy, economic security and emotional welfare (Seely, 2019). The extant literature corroborates this theoretical perspective, as demonstrated by Feinstein et al. (2018b), who found that journalists covering armed conflicts experience substantial resource depletion, resulting in heightened PTSD symptoms and psychological turmoil.

Organizational Support Theory, articulated by Eisenberger et al. (1986), complements COR theory by elucidating the impact of institutional reinforcement on journalists’ psychological fortitude. OST posits that employees cultivate overarching beliefs regarding the extent to which their organization values their contributions and prioritizes their well-being. This theoretical framework elucidates the findings of Šimunjak and Menke (2022) and Koster et al. (2022), who indicated that journalists who perceive robust organizational support report diminished levels of trauma-related symptoms. This theory is particularly relevant when scrutinizing disparities in support mechanisms between Western media entities and local news organizations in conflict-affected areas.

Greenberg et al.’s (2008) Trauma Risk Management model offers a pragmatic framework for understanding trauma prevention and intervention within high-risk professions. The TRiM accentuates the significance of peer support and early intervention, resonating with Backholm and Idås’s (2020) research on the critical role of colleague support in trauma recovery among journalists. This model elucidates the reasons behind the differential resilience exhibited by some journalists, while others suffer pronounced psychological repercussions, as evidenced by the investigations regarding Pakistani journalists by Shah et al. (2020). These theoretical frameworks contribute to the analysis in distinct but complementary ways. Their specific applications to this study are outlined below.

- Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory—Resource Depletion and TraumaThis framework explains how journalists’ repeated exposure to conflict and traumatic events gradually erodes their psychological resources, such as emotional stability, safety, and autonomy. This depletion increases the risk of stress-related disorders, including PTSD.

- Organizational Support Theory (OST)—Institutional SupportOST helps examine how journalists’ perceptions of organizational support influence their capacity to manage trauma. A supportive workplace through policies, leadership, or resources can serve as a protective factor, reducing the intensity of trauma symptoms.

- Trauma Risk Management (TRiM)—Intervention MechanismsTRiM provides a model for understanding how peer support and timely interventions can help prevent long-term psychological harm. It emphasizes the importance of early response and structured peer networks in building resilience among journalists in high-risk environments.

The theoretical assumptions provide the direction for a comprehensive literature review across the following thematic components regarding the psychological analysis and mental health of journalists reporting on conflicts and warfare across diverse global contexts, including the prevalence of psychological trauma (analyzed through COR’s perspective on resource loss), substance use patterns (considered as a compensatory strategy for resource depletion), gender differences (interpreted through the prism of differential access to resources) and coping mechanisms (assessed as strategies for resource management).

By integrating these theoretical perspectives, we can attain a more profound understanding of the reasons certain journalists exhibit greater susceptibility to psychological trauma, the influence of organizational support on outcomes, and the most effective intervention strategies. This framework also facilitates the identification of deficiencies in current research, particularly in the interplay between individual resilience factors and institutional support systems in non-Western contexts.

3. Method

3.1. Search Strategy

This systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines to identify and synthesize relevant empirical studies on journalists’ psychological safety in conflict-affected contexts. A comprehensive search strategy was designed following the procedural recommendations of Bramer et al. (2018), which emphasized both sensitivity and specificity in retrieving academic literature.

Five electronic databases were searched: Google Scholar, Web of Science, Communication and Mass Media Complete, JSTOR, and SCOPUS. The search terms included various combinations of the following keywords using Boolean operators: journalists, trauma, psychological safety, mental health, war reporting, conflict journalism, emotional impact, and occupational stress. Filters were applied to restrict the results to peer-reviewed journal articles published in English, with no restriction on the publication year to ensure temporal breadth.

3.2. Identification and Screening

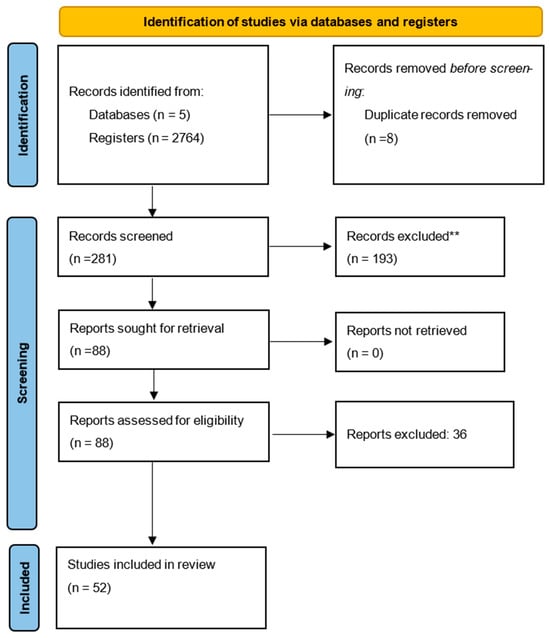

The initial database search yielded 2769 records, comprising 2764 articles from academic registers and 5 from direct database queries. Before screening, 8 duplicate entries were removed, resulting in 2761 unique records.

However, as part of the eligibility calibration and practical screening protocol, relevance filters were applied during the database export to focus on records directly linked to the psychological dimensions of journalism. This step refined the records to a working screening set of 281 articles, which were assessed through a title and abstract review. A total of 229 records were excluded at this stage for lacking substantive focus on journalism practice, psychological trauma, or empirical orientation. This initial screening emphasized empirical engagement with journalists’ experiences of trauma and emotional exposure, particularly in conflict or high-risk environments such as Ukraine.

3.3. Eligibility Assessment

Following the screening phase, 88 full-text articles were retrieved for a detailed eligibility assessment. No articles were excluded because of unavailability (n = 0). Each full-text study was evaluated using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. To be included, studies had to (1) be empirical (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods); (2) involve journalists or journalism trainees as participants; and (3) examine psychological trauma, mental health outcomes, or emotional resilience while reporting, especially during conflict, war, or humanitarian crises. Articles were excluded if they (1) were theoretical or editorial commentaries without primary data, (2) focused solely on audience responses or media framing, or (3) addressed institutional, political, or ethical concerns unrelated to psychological safety.

During the full-text review, 36 studies were excluded for reasons such as an insufficient empirical basis, lack of relevance to trauma-related constructions, or a primary focus on media content rather than journalists’ experiences.

3.4. Final Inclusion

In total, 52 studies met all the inclusion criteria and were retained for the final synthesis. These studies span diverse geopolitical contexts, including sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Europe, and draw on a range of methodologies, from in-depth interviews and psychological assessments to surveys and ethnographic fieldwork. This final set forms the analytical foundation for understanding how journalists experience, internalize, and cope with psychological trauma, particularly in conflict and post-conflict environments.

The full selection process is documented in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram, providing transparency regarding the methodological steps and exclusion rationale (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

If automation tools were used, ** indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools. (Page et al., 2021).

4. Result

Analysis

Inductive thematic analysis was employed to synthesize the findings from the selected articles, allowing key themes to emerge organically from the literature rather than imposing predetermined categories. In terms of geographical and temporal analysis, exponential growth was indicated in research activity, with 44.9% (n = 22) of studies published in the most recent four-year period (2021–2024), compared to only 4.1% (n = 2) in the initial decade (2002–2010). This trajectory indicates the growing academic recognition of journalists’ mental health as a critical research priority. The geographical distribution of studies revealed a significant imbalance, with 53.1% (n = 26) of studies focusing on Western journalists or being conducted by Western institutions; the regional analysis revealed concentrated attention on conflict zones. This analysis revealed substantial gaps in the literature regarding longitudinal studies (only 7% of articles) and neurobiological approaches to trauma (3%), and 22% examined journalists in the Middle East (particularly those covering conflicts in Syria and Iraq), 14% studied South Asian contexts (primarily Pakistan and Afghanistan), and only 11% investigated African journalists, despite the continent’s numerous conflict zones.

Empirical studies dominated the corpus (75.5%, n = 37), with quantitative approaches being the most prevalent (38.8%, n = 19), followed by qualitative methods (22.4%, n = 11). Systematic reviews comprised 8.2% (n = 4) of the literature, indicating limited evidence of synthesis efforts. The interdisciplinary nature of the field was evident in publication patterns, with studies distributed across journalism (26.5%, n = 13), psychology/mental health (24.5%, n = 12), and interdisciplinary (22.4%, n = 11) journals. While this diversity reflects the complexity of journalist trauma, it also presents challenges for evidence synthesis due to the varying methodological standards and assessment tools.

PTSD and trauma exposure emerged as the dominant research themes (30.6%, n = 15), followed by general mental health and psychological well-being (24.5%, n = 12). Notably, resilience and coping mechanisms accounted for 16.3% of the studies, indicating a shift toward protective factors rather than solely focusing on pathological outcomes. Frontline and war correspondents constituted the most studied population (36.7%, n = 18), while general newsroom journalists comprised 30.6% (n = 15). This distribution suggests an appropriate focus on high-risk populations while acknowledging broader occupational vulnerability.

The analysis identified several methodological limitations that compromised the field’s evidence base.

- First, the geographical bias toward Western contexts limits the generalizability of the findings to journalists in diverse cultural and economic environments.

- Second, methodological heterogeneity, which reflects the complexity of the phenomenon, impedes systematic comparison and meta-analysis.

- Third, the predominance of cross-sectional designs (evident in the lack of longitudinal studies) restricts our understanding of trauma trajectories and causal relationships.

- Fourth, intervention research remains notably absent, with most studies focusing on prevalence rather than on treatment effectiveness.

Of the articles that met the inclusion criteria, 59.09% (52 articles) addressed trauma-related symptoms such as PTSD, anxiety, or depression. In addition, 18% examined substance use patterns as coping mechanisms, 15% investigated gender differences in trauma experiences, 14% evaluated institutional support structures, and 11% explored individual coping strategies. The geographical distribution of studies revealed a significant imbalance: 53% of the studies focused on Western journalists or were conducted by Western institutions, 22% examined journalists in the Middle East (particularly those covering conflicts in Syria and Iraq), 14% studied South Asian contexts (primarily Pakistan and Afghanistan), and only 11% investigated African journalists, despite the continent’s numerous conflict zones. Methodologically, 64% of the studies utilized quantitative approaches with standardized psychological assessment tools, 27% employed qualitative methods including in-depth interviews and focus groups, and 9% used mixed methods designs.

5. Prevalence of Psychological Trauma and Mental Health Disorders Among Journalists Reporting on War and Conflict

While a large body of literature discusses the physical safety, assault, and harassment of journalists globally, the issues of trauma and mental health of journalists covering terrorism have not been adequately reported. However, the prevalence of psychological trauma and mental health disorders among journalists covering war, conflict, or terrorism has garnered increasing attention in recent years. This focus is driven by the unique and often perilous nature of their work, which exposes them to traumatic events that can cause psychological distress. Studies indicate that journalists covering conflict zones experience high rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety, often comparable to those observed in combat veterans (Feinstein et al., 2015, 2016; MacDonald et al., 2021). This shows that journalists exhibit significantly higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depression than non-war journalists. Shah et al. (2020) revealed a high prevalence of trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms among regional journalists in Pakistan, with all participants having covered at least one traumatic event. Journalists in Mexico suffer from higher rates of mental health issues such as PTSD, anxiety, and depression compared to the general population, and many of them have stopped covering certain stories due to intimidation and threats from drug cartels, undermining press freedom (Woodman, 2020).

Studies have indicated that journalists covering conflict zones exhibit psychological distress comparable to that of combat veterans. For instance, Osmann et al. (2020a) found that Afghan journalists reported high levels of PTSD and depression, significantly exceeding those of their domestic counterparts who covered nonviolent news stories. Similarly, Koster et al. (2022) documented elevated PTSD levels among Pakistani journalists exposed to war-related violence and natural disasters, reinforcing the link between traumatic exposure and mental health deterioration. These findings are consistent across various regions, as evidenced by studies in the MENA region, where frontline journalists reported significant mental and physical health consequences related to their work (Chadli et al., 2022).

A seminal study of 140 war journalists found a lifetime PTSD prevalence of 28.6%, exceeding the rates observed in police officers and approaching those of combat veterans. Symptoms such as intrusive memories, hyperarousal, and emotional numbing are common and are often exacerbated by repeated exposure to life-threatening events (e.g., shootings and mock executions). Azma (2024) cited Shah et al. (2020). Hill et al. (2020), Motta (2023) and Dubberley (2020), argue that trauma is involved in all cycles of news gathering, production, and consumption. According to him, audiences are also victims of trauma because they consume the content of the news story. Depression rates among war journalists also surpass general population averages, with Israeli journalists reporting higher somatic and anxiety-related distress than their Western counterparts (Blakey et al., 2024). In contrast, Miller and Rasmussen (2010) argued that trauma-focused approaches overemphasize the impact of direct war exposure on mental health and fail to consider the contributions of daily stressors.

A systematic review of the literature highlights that journalists face many stressors, including direct exposure to violence, the threat of physical harm, and the emotional toll of reporting human suffering (Smith et al., 2017). For instance, a study conducted among Iranian journalists revealed a strong correlation between frequent exposure to life-threatening events and the development of PTSD symptoms (Feinstein et al., 2016). Similarly, research on Pakistani journalists found that those reporting from conflict areas exhibited significant psychological distress, with many experiencing PTSD and depression symptoms (Koster et al., 2022). This distress is exacerbated by the nature of their work, which often involves covering traumatic events without adequate psychological support (Chadli et al., 2022).

Moreover, the psychological impact of war and conflict journalism extends beyond the immediate exposure to trauma. Studies have shown that the cumulative effect of reporting violent events can lead to chronic mental health issues, including moral injury, which is distinct from PTSD but equally debilitating (Feinstein et al., 2018a). Journalists often grapple with feelings of guilt and helplessness, particularly when they are unable to prevent suffering or when their reporting inadvertently contributes to further trauma (Feinstein et al., 2018b; Backholm & Idås, 2020). This emotional burden is compounded by the lack of institutional support and resources for mental healthcare within news organizations, which can leave journalists feeling isolated and vulnerable (Ogunyemi & Price, 2023a, 2023b).

The need for trauma-informed education and training for journalists is increasingly recognized as essential for mitigating these psychological risks. Programs aimed at enhancing trauma literacy among journalism students are advocated to prepare them for the emotional challenges they may face in their careers (Ogunyemi & Price, 2023a, 2023b). Such initiatives emphasize the importance of understanding both psychological responses to trauma and the needs of trauma victims, fostering a more supportive environment within newsrooms (Ogunyemi & Price, 2023a, 2023b).

The prevalence of psychological trauma and mental health disorders among journalists reporting on war, conflict, or terrorism is a pressing issue that necessitates further research and intervention. Evidence suggests that these professionals are at a heightened risk of PTSD, depression, and anxiety due to their exposure to traumatic events. Addressing these challenges through comprehensive mental health support and trauma-informed education is crucial for journalists’ well-being and the integrity of the journalism profession.

6. Substance Use Among Journalists Facing Trauma Related to Conflict/War Reporting

The literature on substance use among journalists facing trauma, mental health challenges, and psychological disorders because of reporting on war, conflict, and disaster is largely focused among Western journalists who cover wars in the Middle East and some parts of the African continent, highlighting significant concerns regarding the psychological well-being of these professionals. Journalists often encounter traumatic events that can lead to severe mental health issues, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety, which can influence their substance use behaviors. Despite the limited data, Aoki et al. (2013) highlighted the preliminary evidence of problematic alcohol use in journalism. However, the review noted insufficient evidence to establish dependence rates, revealing a critical research gap in the PTSD/depression literature.

The psychological toll of reporting traumatic events often leads to maladaptive coping mechanisms, including substance use, among journalists. For example, Feinstein and Starr (2015) noted that journalists covering the Syrian conflict exhibited higher levels of depression and alcohol consumption than those who reported on previous conflicts, indicating a potential link between trauma and increased substance use. Smith et al. (2017) emphasized the necessity for media organizations to implement trauma-informed practices to mitigate these risks, suggesting that better support systems could reduce the prevalence of PTSD and associated substance use among journalists.

Organizational support is critical for addressing the mental health challenges faced by journalists. Studies have shown that journalists who perceive their workplace as supportive are less likely to experience severe mental health problems (Šimunjak & Menke, 2022). For instance, Šimunjak and Menke (2022) highlighted the importance of workplace well-being and support systems in mitigating the emotional toll of reporting traumatic events (Šimunjak & Menke, 2022). Additionally, the implementation of resilience training and mindfulness strategies has been suggested to enhance journalists’ coping mechanisms and reduce the likelihood of substance use as a maladaptive response to stress (Martin & Murrell, 2020).

Moreover, the stigma surrounding mental health issues within the journalism profession exacerbates the challenges faced by journalists. For example, one study found that many Ecuadorian journalists reported difficulties coping with traumatic experiences, often because of the stigma associated with seeking help for mental health problems (Bustamante et al., 2021). Other research has also found that stigma can lead to increased substance use, as journalists may turn to alcohol or drugs to cope with psychological distress (Englund et al., 2023).

The intersection of trauma exposure, mental health challenges, and substance use among journalists is a critical area of concern that requires further research. Evidence suggests that journalists covering war and conflict are at significant risk of developing PTSD, depression, and anxiety, which can lead to increased substance use.

7. Risk Factors and Trauma Exposure

The exposure of journalists to traumatic events while reporting on wars, disasters, and conflicts is a significant concern, particularly in regions such as Africa, where violence and instability are prevalent. For instance, Osmann et al. (2020b) conducted a mapping review. They concluded that the prevalence of PTSD among journalists is notably elevated, with factors such as career length, exposure frequency, and inadequate social support contributing to increased psychological distress among journalists. Similarly, Williams and Cartwright (2021) found that UK journalists covering war reported that PTSD symptoms were significantly associated with their experiences in conflict zones, with 6–12% of participants exhibiting severe symptoms. This aligns with the findings of Feinstein et al. (2018b), who reported that frontline journalists in Iraq experienced an average of 22 traumatic events in their careers, underscoring trauma exposure’s cumulative nature.

Fahmy et al. (2024) found that Palestinian journalists in Gaza experienced intense trauma marked by physical danger, loss of loved ones, and emotional exhaustion. Despite grieving personal losses, many continued to report, often feeling morally obligated to document the war. The study also highlighted the compounding effects of algorithmic censorship and professional isolation, contributing to what the authors called “layers of unresolved grief, anger, and resilience” (p. 177). Although not directly focused on journalists, Malecki et al. (2023) found that repeated exposure to war-related media, even as a consumer, was linked to higher anxiety, distress, and reduced resilience. This points to how sustained interaction with conflict content can carry emotional risks, even for those who do not report directly.

In the African context, studies have shown that journalists covering violence and conflict are particularly vulnerable. For example, Koster et al. (2022) reported that journalists covering natural disasters experience higher levels of PTSD and anxiety, suggesting that the nature of the reported events significantly impacts mental health outcomes. These findings were also shown in the related work by Shah et al. (2020), who found that journalists in conflict-prone areas of Pakistan face severe stress due to the violent environment and scrutiny of their reporting. Such findings are critical as they reflect the broader implications for journalists operating in similarly volatile regions across Africa.

The psychological effects of reporting on extreme violence have also been documented in studies focusing on Kenyan journalists, where exposure to traumatic events was linked to high rates of PTSD comparable to those seen in combat veterans (Feinstein et al., 2015). This suggests that the dangers faced by journalists in conflict zones are profound and can lead to long-term psychological impairments. Chadli et al. (2022) emphasized that the mental and physical health consequences of frontline reporting in the MENA region are underreported, indicating a need for greater awareness and support for journalists in similar contexts.

Similarly, the social dynamics surrounding journalism in conflict zones can exacerbate mental health problems. The stigma associated with seeking help for mental health problems can deter journalists from accessing the necessary support, as noted by research conducted by Idås et al. (2019), who explored the role of social support in mitigating PTSD symptoms among journalists. These findings highlight the importance of fostering supportive environments within news organizations to help journalists cope with the psychological toll of their work.

8. Cross-Cultural and Gender Differences

Gender-specific trauma experienced by female journalists reporting war and conflict is a critical area of research that highlights the unique challenges women face in this profession. Female journalists often encounter not only the psychological toll of covering traumatic events but also gendered violence and discrimination, which exacerbate their experiences of trauma.

The intersection of gender and trauma is particularly important in advancing our understanding of the effects of traumatic experiences among female journalists; however, nascent research has been conducted to explore the plight of female journalists in armed conflicts. Among the few studies that have looked at this dynamic, such as the work undertaken by Lee and Park (2023), it is highlighted that female journalists are more likely to experience violent threats than their male counterparts, which significantly contributes to their psychological distress. This gendered aspect of trauma is compounded by societal expectations and the additional pressures female journalists face as they navigate hostile environments both in the field and online. For instance, Zviyita and Mare (2023) found that a substantial percentage of female journalists experienced online gender-based violence, which could further exacerbate their mental health challenges.

The emotional toll of witnessing violence and loss is particularly high for female journalists. García and Ouariachi (2021) found that nearly 87% of Syrian journalists reported having colleagues who died while covering the war, leading to profound sorrow and psychological distress among them. This emotional burden is not only a result of the immediate dangers of conflict reporting but also stems from the broader context of gendered violence and discrimination that female journalists face, which can lead to feelings of isolation and helplessness (Osmann et al., 2020a).

In summary, female journalists covering war and conflict face a unique set of challenges that contribute to significant psychological trauma. The interplay of gendered violence, the psychological impact of conflict exposure, and the emotional toll of witnessing trauma creates a complex landscape of mental health risks for women in this profession.

9. Coping Mechanisms and Institutional Support

While Dahan et al. (2024) show that religiosity, personal resilience, and national resilience reduce anxiety and acute stress and that religiosity aligns with higher resilience and post-traumatic growth (PTG), there’s growing evidence that many journalists develop coping strategies to manage their psychological well-being. These include informal peer support, which is crucial for resilience, and various personal safety measures. However, scholars like García and Ouariachi (2021) and Frey (2023) argue that the effectiveness of these measures can vary, and the trauma experienced can sometimes act as both a paralyzing and empowering factor. Some journalists report post-traumatic growth, indicating a complex relationship between trauma exposure and personal development (Frey, 2023). Backholm and Idås (2020) posit that proactive measures by media organizations can help prevent long-term psychological harm to journalists and reduce their risk of causing further harm to victims. Few studies have focused on coping mechanisms for trauma-related issues among journalists who report on wars and conflicts. However, recent studies have indicated that problem-focused coping strategies, which involve actively addressing stressors, are more effective than avoidant coping strategies, which can exacerbate psychological distress. For instance, Englund et al. (2023) found that journalists who employed problem-focused coping reported better management of trauma-related stress than those who relied on avoidance of stress. This aligns with Yang and Ha’s (2019) findings; they emphasized that deliberate rumination and problem-focused coping are associated with positive post-traumatic growth among individuals exposed to trauma. These studies suggest that fostering effective coping strategies is essential for journalists to navigate the psychological challenges of their work.

However, institutional support plays a crucial role in enhancing journalists’ resilience and coping abilities. Markovikj and Serafimovska (2023) highlighted the importance of integrating mental health resilience training into journalism curricula, noting that education on trauma can significantly improve journalists’ trauma literacy and coping strategies. This is particularly relevant in high-stress reporting environments, where understanding the psychological impacts of trauma can empower journalists to seek help and utilize effective coping mechanisms. Furthermore, trauma literacy can help journalists recognize symptoms of distress in themselves and their colleagues, promoting a culture of support within news organizations (Shilpa et al., 2023).

The organizational environment significantly influences journalists’ mental health outcomes. Studies have shown that supportive workplace culture can mitigate the effects of trauma exposure. For example, Koster et al. (2022) found that journalists who perceived their organizations as supportive reported lower PTSD and anxiety levels (Koster et al., 2022). Conversely, journalists in high-stress environments with little institutional support are more likely to experience severe psychological distress and burnout (Shah et al., 2020). This highlights the necessity for media organizations to implement comprehensive mental health support systems, including access to counseling and peer-support programs.

Moreover, the stigma surrounding mental health issues in the journalism profession can hinder journalists from seeking help. O’Brien (2020) discussed the challenges journalists face in reporting on mental health topics, which can reflect their own struggles and contribute to a culture of silence around mental health issues. Therefore, the literature underscores the importance of effective coping strategies and robust institutional support for journalists facing trauma and psychological disorders. Problem-focused coping mechanisms are more beneficial than avoidant strategies, and trauma literacy and resilience training can empower journalists to effectively manage their mental health. Furthermore, supportive organizational environments are crucial in mitigating the psychological impact of trauma exposure.

Despite the growing awareness, institutional support remains inconsistent. Some scholars, such as Feinstein et al. (2014), Pyevich et al. (2003), and Reinardy (2011), argue that media institutions often prioritize technical skills over mental health preparedness, leaving journalists unprepared for traumatic exposure. A report from Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (2020) acknowledges that institutional support is often fragmented, with counseling services underfunded or inaccessible, particularly in Global Southern countries. Freelancers, who constitute a growing proportion of conflict reporters, face heightened exclusion owing to the absence of employer-provided healthcare. Cultural taboos surrounding mental health in regions like the Middle East, Africa, and Asia discourage help-seeking, while newsroom cultures glorify “toughness,” perpetuating silence.

Many journalists report a glaring lack of organizational support and prevention structures, often linked to problematic newsroom cultures characterized by sexism, machismo, and fierce competition (Obermaier et al., 2023). This lack of support can lead to increased mental health issues, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression (Dadouch & Lilly, 2020). Frey (2023) argues that journalists often rely on informal peer support rather than institutional mechanisms, which are insufficiently developed to address their needs. Obermaier et al. (2023) further insist that there is a need for more institutional training focused on trauma, mental health, and psychological well-being for journalists and editorial staff.

Table 1 shows a summary of the literature reviewed in this study.

Table 1.

Summary of the reviewed literature.

10. Conclusions and Directions for Future Research

The extensive body of scholarly work concerning the psychological safety of journalists engaged in reporting on warfare, terrorism, and conflict delineates a complex terrain characterized by trauma exposure, mental health adversities, and institutional deficiencies that necessitate immediate scholarly and practical intervention. As primary observers of human distress and violence, journalists encounter remarkable threats to their psychological well-being, which frequently remain inadequately addressed in both empirical investigations and professional practice settings. Empirical studies have consistently indicated that journalists operating within conflict zones exhibit rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) comparable to those observed in combat veterans, with foundational research conducted by Feinstein et al. (2002) uncovering a lifetime prevalence of PTSD of 28.6% among war correspondents. This psychological burden transcends PTSD, encompassing additional mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders, thereby creating a complex and multifaceted strain on journalists’ mental health. Comprehensive investigations conducted by Feinstein et al. (2014, 2015, 2016, 2018b) across diverse contexts, from Kenya to Iran to Syria, elucidate a discernible pattern: recurrent exposure to traumatic incidents depletes psychological resources and precipitates significant mental health decline over time.

The dose–response paradigm linking trauma exposure to psychological distress has emerged as a significant finding in the literature. As outlined by Osmann et al. (2020a) and Williams and Cartwright (2021), journalists engaged in covering high-intensity conflicts or extended assignments report a higher severity of PTSD symptoms. This correlation is particularly pronounced among freelance and local journalists situated in precarious regions who frequently lack institutional support, as evidenced by investigations regarding Pakistani journalists conducted by Shah et al. (2020) and Koster et al. (2022). Cultural and sex disparities significantly influence experiences of trauma and the mechanisms employed for coping. Research indicates that Israeli journalists exhibit elevated rates of depression and somatic symptoms, whereas their Western counterparts demonstrate higher instances of PTSD and alcohol consumption, suggesting cultural determinants in the expression and management of trauma. Gender emerges as a pivotal variable, with investigations by Lee and Park (2023) and Zviyita and Mare (2023) highlighting that female journalists encounter additional complexities of trauma resulting from gendered violence and discrimination, both in operational contexts and online environments. This intersectionality of gender and trauma engenders unique psychological challenges that remain underexplored, particularly in conflict zones in Africa and the Middle East.

Despite these stressors, many journalists have developed coping mechanisms that enhance their resilience. Research conducted by Englund et al. (2023) and Yang and Ha (2019) revealed that problem-focused coping strategies are more efficacious than avoidant strategies in managing trauma-related stress. Informal peer support is particularly salient, as journalists frequently depend on their colleagues rather than formal institutional frameworks to navigate and process traumatic experiences. Some journalists have reported instances of post-traumatic growth, indicating a nuanced relationship between trauma exposure and personal development (Frey, 2023). However, institutional support, an essential facilitator of psychological outcomes, remains deficient in journalism. Empirical investigations have consistently revealed substantial deficiencies in organizational readiness and responses to trauma. In addition, according to Feinstein et al. (2014), Pyevich et al. (2003), and Reinardy (2011), media organizations frequently prioritize technical competencies over mental health preparedness, thereby rendering journalists inadequately equipped to confront the psychological adversities they encounter in the field. This deficit in support is further exacerbated by detrimental newsroom cultures characterized by sexism, machismo, and competitive dynamics, as articulated by Obermaier et al. (2023).

The stigma associated with mental health challenges is another substantial impediment to seeking support. O’Brien (2020) and Bustamante et al. (2021) illustrate how such stigma can inhibit journalists from recognizing their psychological distress or seeking assistance, thereby fostering a culture of silence that intensifies mental health difficulties. This stigma is particularly pronounced in areas where cultural prohibitions regarding mental health are more pronounced, consequently isolating journalists from their suffering. Emerging interventions have the potential to address these issues. Trauma-informed training programs, such as those endorsed by the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, underscore the importance of pre-deployment mental preparation, effective stress management and post-assignment debriefing. Educational strategies aimed at enhancing trauma literacy, as examined by Ogunyemi and Price (2023a) and Markovikj and Serafimovska (2023), provide avenues for incorporating mental health awareness into journalism education frameworks. These interventions acknowledge that psychological safety requires both individual and systematic organizational support.The geographic distribution of extant research reveals notable disparities in the literature. While 53% of scholarly inquiries concentrate on Western journalists, only 11% investigate the experiences of African journalists, despite the continent’s myriad conflict zones. This disparity constrains our understanding of trauma experiences across diverse cultural landscapes and emphasizes the need for more inclusive research agendas that prioritize journalists’ experiences in the Global South. Several research trajectories have emerged as critical priorities. A heightened emphasis on the Global South would rectify significant gaps in understanding of trauma experiences in regions where local journalists encounter systemic neglect of safety. Investigating institutional accountability could catalyze organizational transformations in resource allocation for journalists’ safety and well-being. Finally, developing ethical frameworks that reconcile journalistic integrity with the imperative of self-care would provide practical guidance for journalists operating in high-risk environments.

The psychological ramifications of conflict reporting necessitate immediate attention from researchers, media organizations, and policymakers. As custodians of truth in conflict-riddled areas, journalists’ mental health transcends individual concerns and is a matter of public significance. An interdisciplinary approach that integrates insights from neuroscience, cultural psychology, and organizational ethics can mitigate the psychological risks faced by journalists and promote resilience in this vital profession to ensure its survival. Only through comprehensive strategies that address both individual and institutional elements can we safeguard the psychological well-being of those who bear witness to the most harrowing moments in human history.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aoki, Y., Malcolm, E., Yamaguchi, S., Thornicroft, G., & Henderson, C. (2013). Mental illness among journalists: A systematic review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59(4), 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azma, S. (2024). Trauma Exposure across the news cycle and the biotypes of PTSD in war journalists. Seeds of Science Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backholm, K., & Idås, T. (2020). In the aftermath of a massacre: Traumatization of journalists who cover severe crises (pp. 236–254). Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakey, S. M., Dillon, K. H., McFarlane, A., & Beckham, J. C. (2024). Disorders specifically associated with stress: PTSD, complex PTSD, acute stress reaction, adjustment disorder. In Tasman’s psychiatry (pp. 1–53). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bramer, W. M., De Jonge, G. B., Rethlefsen, M. L., Mast, F., & Kleijnen, J. (2018). A systematic approach to searching: An efficient and complete method to develop literature searches. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 106(4), 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, B., Rodríguez-Hidalgo, C., Cisneros-Vidal, M., Rivera, D., & Torres-Montesinos, C. (2021). Ecuadorian journalists’ mental health influence on changing job desires: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadli, L., Haq, F., Okasha, A., & Attou, R. (2022). Posttraumatic mental and physical consequences of frontline reporting in the MENA region. The Open Public Health Journal, 15(1), e187494452212090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadouch, Z., & Lilly, M. (2020). Post-trauma psychopathology in journalists: The influence of institutional betrayal and world assumptions. Journalism Practice, 15, 955–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, S., Bloemhof-Bris, E., Segev, R., Abramovich, M., Levy, G., & Shelef, A. (2024). Anxiety, posttraumatic symptoms, media-induced secondary trauma, posttraumatic growth, and resilience among mental health workers during the Israel-Hamas War. Stress and Health, 40(5), e3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubberley, S. (2020). Finally recognizing secondary trauma as a primary issue. Columbia Journalism Review. Available online: https://www.cjr.org/analysis/finally-recognizing-secondary-trauma-as-a-primary-issue.php (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, L., Johannesson, K., & Arnberg, F. (2023). Reporting under Extreme Conditions: Journalists’ Experiences of Disaster Coverage. Frontiers in Communication, 8, 1060169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, S. S., Salama, M., & Alsaba, M. R. (2024). Shattered lives, unbroken stories: Journalists’ perspectives from the frontlines of the Israel–Gaza war. Online Media and Global Communication, 3(2), 151–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S., Malik, J. A., Hanif, R., & Ali, H. (2023). Primary appraisal of trauma exposure and mental health symptoms among journalists. Foundation University Journal of Psychology, 7(2), 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A., Audet, B., & Waknine, E. (2014). Witnessing images of extreme violence: A psychological study of journalists in the newsroom. JRSM Open, 5(8), 2054270414533323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A., Feinstein, S., Behari, M., & Pavisian, B. (2016). Psychological well-being of Iranian journalists: A descriptive study. JRSM Open, 7(12), 2054270416675560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A., Osmann, J., & Patel, V. (2018a). Symptoms of PTSD in frontline journalists: A retrospective examination of 18 years of war and conflict. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 63(9), 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinstein, A., Owen, J., & Blair, N. (2002). Hazardous profession: War, journalists, and psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(9), 1570–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinstein, A., Pavisian, B., & Storm, H. (2018b). Journalists covering refugee and migration crises are affected by moral injury, not PTSD. JRSM Open, 9(3), 2054270418759010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A., & Starr, S. (2015). Civil War in Syria: The Psychological Effects of Journalists. Journal of Aggression Conflict and Peace Research, 7(1), 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A., Wang, J., & Owen, J. (2015). The psychological effects of reporting extreme violence: A study of Kenyan journalists. JRSM Open, 6(9), 2054270415602828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, E. (2023). Preparing for risks and building resilience. Journalism Studies, 24, 1008–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L., & Ouariachi, T. (2021). Syrian journalists covering the war: Assessing perceptions of fear and security. Media War & Conflict, 16(1), 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, N., Langston, V., & Jones, N. (2008). Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) in UK Armed Forces. BMJ Military Health, 154(2), 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D., Luther, C. A., & Slocum, P. (2020). Preparing future journalists for trauma on the job. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 75(1), 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idås, T., Backholm, K., & Korhonen, J. (2019). Trauma in the newsroom: Social support, post-traumatic stress, and post-traumatic growth among journalists working with terror. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1620085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukes, S. (2015). Journalists at risk–looking beyond physical safety. In The future of journalism—Risks, threats and opportunities. Cardiff University. (Unpublished). [Google Scholar]

- Koster, S., Koot, H., Malik, J., & Sijbrandij, M. (2022). Associations among traumatic experiences, threat exposure, and mental health among Pakistani journalists. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 35(2), 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N., & Park, A. (2023). How does online harassment affect Korean journalists? The effects of online harassment on journalists’ psychological problems and intention to leave the profession. Journalism, 25(4), 900–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levaot, Y. (2013). Trauma and psychological distress observed in journalists: A comparison of Israeli journalists and their Western counterparts. Israel Journal of Psychiatry, 50(2), 118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, J. B., Hodgins, G., Saliba, A. J., & Metcalf, D. A. (2021). Journalists and depressive symptoms: A systematic literature review. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 24(1), 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, W. P., Bilandzic, H., Kowal, M., & Sorokowski, P. (2023). Media experiences during the Ukraine war and their relationships with distress, anxiety, and resilience. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 165, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markovikj, M., & Serafimovska, E. (2023). Mental health resilience in the journalism curriculum. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 78(2), 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F., & Murrell, C. (2020). You need a thick skin in this game: Journalists’ attitudes to resilience training as a strategy for combating online violence. Australian Journalism Review, 42(1), 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K. E., & Rasmussen, A. (2010). War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine, 70(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, R. W. (2023). Secondary Trauma: Silent Suffering and Its Treatment. Springer Cham. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 10(4), 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermaier, M., Wiedicke, A., Steindl, N., & Hanitzsch, T. (2023). Reporting trauma: Conflict journalists’ exposure to potentially traumatizing events, short- and long-term consequences, and coping behavior. Journalism Studies, 24, 1398–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, A. (2020). Reporting on mental health difficulties, mental illness and suicide: Journalists’ accounts of the challenges. Journalism, 22(12), 3031–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunyemi, O., & Price, L. (2023a). Exploring the attitudes of journalism educators to teach trauma-informed literacy: An analysis of a global survey. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 78(2), 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunyemi, O., & Price, L. (2023b). Introduction: Trauma literacy in global journalism: Toward an education agenda. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 78(2), 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmann, J., Dvorkin, J., Inbar, Y., Page-Gould, E., & Feinstein, A. (2020a). The emotional well-being of journalists exposed to traumatic events: A mapping review. Media War & Conflict, 14(4), 476–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmann, J., Khalvatgar, A., & Feinstein, A. (2020b). Psychological distress in Afghan journalists: A descriptive study. Journal of Aggression Conflict and Peace Research, 12(3), 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetxlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hrobjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., Moher, D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, M., McMahon, C., O’Donovan, A., & O’Shannessy, D. (2019). Building journalists’ resilience through mindfulness strategies. Journalism, 22(7), 1647–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyevich, C. M., Newman, E., & Daleiden, E. (2003). The relationship among cognitive schemas, job-related traumatic exposure, and posttraumatic stress disorder in journalists. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16(4), 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoli, L. O. (2024). “If it bleeds it leads”: The visual witnessing trauma phenomenon among journalists in East Africa. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 79(3), 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinardy, S. (2011). Newspaper journalism in crisis: Burnout on the rise, eroding young journalists’ career commitment. Journalism, 12(1), 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. (2020). Freelancing & mental health. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/freelancing-mental-health (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Seely, N. (2019). Journalists and mental health: The psychological toll of covering everyday trauma. Newspaper Research Journal, 40(2), 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. F. A., Jan, F., Ginossar, T., McGrail, J. P., Baber, D., & Ullah, R. (2020). Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder among regional journalists in Pakistan. Journalism, 23(2), 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilpa, K., Kumari, A., Das, M., Sharma, T., & Biswal, S. (2023). Exploring trauma literacy quotient among Indian journalists and a way forward in post-pandemic era: A case study of India. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 78(2), 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqua, A., & Iqbal, M. Z. (2024). Journalists and exposure to trauma: Exploring perceptions of PTSD and resilience among Pakistan’s conflict reporters. Journalism Practice, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R., Drevo, S., & Newman, E. (2017). Covering traumatic news stories: Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder among journalists. Stress and Health, 34(2), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z., McDonnell, D., Cheshmehzangi, A., Bentley, B. L., Ahmad, J., Šegalo, S., da Veiga, C. P., & Xiang, Y. T. (2023). Media induced war trauma amid conflicts in Ukraine. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 18(4), 908–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimunjak, M., & Menke, M. (2022). Workplace well-being and support systems in journalism: Comparative analysis of Germany and the United Kingdom. Journalism, 24(11), 2474–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S., & Cartwright, T. (2021). Post-traumatic stress, personal risk and post-traumatic growth among UK journalists. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1881727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, S. (2020). “I have suffered death threats and they killed my pet dogs”: Mexican journalists work in war-like conditions. Many are suffering terrible mental illnesses because of it. Index on Censorship, 49(3), 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., & Ha, Y. (2019). Predicting posttraumatic growth among firefighters: The role of deliberate rumination and problem-focused coping. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zviyita, I., & Mare, A. (2023). Same threats, different platforms? Female journalists’ experiences of online gender-based violence in selected newsrooms in Namibia. Journalism, 25(4), 779–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).